Abstract

The Project Planning, Monitoring, Systematizing, and Learning (PlaMSyL) method was developed in a period of ten years (1996–2005) and has expanded since then to improve the results of development and emergency projects in developing countries, focusing mainly on the monitoring and learning process of different local stakeholders beyond the deliverables into the changes and impacts of outcomes. It has been applied in different countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America between 2006 and 2016. Today, it is taught in universities to students of pre- and post-grade levels. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals are part of the UN Agenda 2030, signed by 193 governments in 2015, contain 169 Targets, and 232 indicators of social well-being (health, education, zero hunger, equality, and gender), and for economic (food production, industry, zero poverty, consumption, infrastructure, and technology), and ecological development (water, climate, governance, and biodiversity) preserving the planet from a collapse and ensuring the sustainable well-being of all. The SDGs provide the framework for a new circular economy based on clean energy and zero greenhouse gases. One basic principle of the SDG 2030 is “Leave No One Behind” and is what drives to work with the local governments and communities in a bottom-up approach, coordinating with the national level to set up appropriate policies. The PlaMSyL method has been practiced by different professional teams of education, health, engineering, agriculture, disaster risk reduction, and ecologists, and for this reason, the paper explains the use of the PlaMSyL method with the indicators and targets of the SDGs, and the resilience to facilitate local project teams and stakeholders to use the SDGs participatively as a framework, and as a metrics and communication tool.

1. Analysis of the Situation in Development

Important Problems

Technical teams of local governments and NGOs in developing countries know that community leaders and families have a large experience in resilient development due to the many hazards affecting their production and social well-being being exacerbated today by climate change, the growing inequality in opportunities, violence between national actors, the pandemic, and large disasters which hinder their sustainable development, making the local development context dynamic, emergent, and complex [1]. One main problem that goes on is that policies are written at a national level in a top–down format with little understanding and non-participative discussion of local experiences.

The UN Agenda 2030 with 17 SDGs [2] and 169 targets, plus the indicators, provides a framework that integrates the solutions to achieve a harmonious, integral, and resilient development. Even though 163 countries are reporting advances toward those goals [3], most of that information in developing countries is still a national average, with little insertion into the local level of communities and municipalities, a fact that was observed in the evaluation of the Millennium Development Goals by disaggregating the results in 2013 by groups of people: girls and boys in education and health, rural and urban in WASH indicators and other services, indigenous and non-indigenous persons, and between income groups [4].

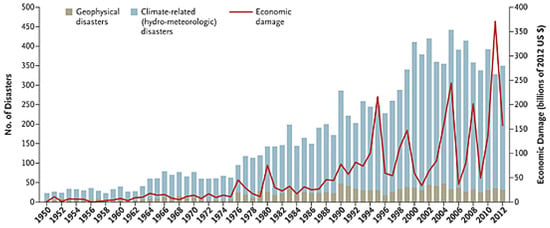

Figure 1 shows the major negative impacts of climate change and related disasters.

Figure 1.

AccuWeather. The steady increase in climate-related natural disasters.

The UN Unfinished Agenda provided a justification for the new Agenda 2030; however, to avoid doing similar process when pursuing the average country information only, there is an urgent need to work bottom-up, starting at local levels.

2. Some Important Advances in the Last Decades

2.1. Local Participation

The organizations that support local development, including NGOs, municipal governments, and international organizations with local presence, have seen in the last decades advances in community participation, and the use of project-planning tools for the scope of development projects changed positively from a top-down and lineal method to a more participative, flexible, inclusive, non-lineal, and innovative approach.

Figure 2 shows that the practice in development and emergency projects has evolved in the participation of local actors from a contribution of local materials and hand labour, to the training for the operation and maintenance of their projects, to a resilient preparation for highly probable emergencies, to involvement in the evaluation of their own projects, committees, and authorities up to the higher level of conscious participation regarding the sustainability of their projects, where authorities and participants know their duties and rights.

Figure 2.

The five levels of local participation Adapted by F. Guachalla (2021) from E. M. Galarza, Ministry of Education, Guatemala.

2.2. Project Planning, Monitoring, Systematizing, and Learning—PlaMSyL Method

PlaMSyL was developed in an inclusive, participatory, and innovative effort between 1996 and 2005, achieving development projects with a high level of involvement from local actors including community leaders, local authorities, financial institutions, project teams, families, and NGOs within a dynamic, emergent, and complex context in rural and peri–urban areas [5].

PlaMSyL was later applied in other countries for strengthening the local resilience in Latin America and in large emergencies in the Philippines and Sierra Leone [6]. Currently, PlaMSyL is taught at universities in pre- and post-degrees to facilitate the application of the method to professionals in NGOs, local government technical teams, and organizations that have presence in the context of the new paradigm of the SDG 2030 and resilience [7].

Main Characteristics of PlaMSyL.

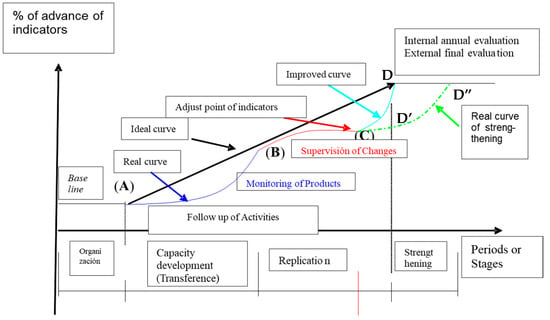

This method began with the participatory design of the Sys-Curve in Figure 3 in developing projects, where A is the starting monitoring point and D the expected planning target in a hypothetically linear solution. B is the point where the community team reaches while the project team is training them, and C, where the community team reaches working alone with a necessary team reinforcement. D” and D’ are the real achieved goals when the project ends, with/without extension.

Figure 3.

Systematization Curve. F. Guachalla, 2005.

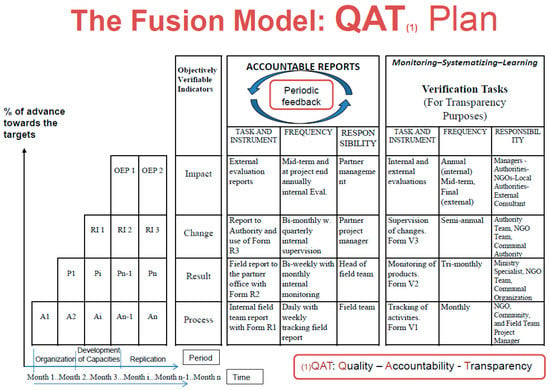

This Sys-Curve is more real and consistent with the advances towards the project goals [5], and it is based on the fusion model Plan-QAT (for quality, accountability, and transparency, Figure 4) that integrates the results-oriented log-chain with the outcome mapping process-oriented learning pathway on behaviour change [8].

Figure 4.

The fusion model Plan-QAT. F. Guachalla, 2005.

The method achieves the monitoring of the advances of the change indicators of outcomes, and the impact indicators of the specific objective measured in different periods (quarterly and annually) beyond the frequent follow-up of process and product indicators (weekly and monthly). It also facilitates periodic feedback loops (Figure 4) with stakeholders based on the systematization of the field information, calculation, and qualification of indicators, as well the participatory learning for improvements reached in consensus during the implementation of the project, which is different to the evaluation that usually brings the analysis of the results at the end of a project that is far too late for improvements [9].

2.3. The UN Agenda 2030 with Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Agenda “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” was signed by 193 countries on the 25 September 2015 in the United Nations based on the principle of “Leave No One Behind”. It was organized in five groups: people with five SDGs one to five, planet with five SDGs six and twelve to fifteen, prosperity with five SDGs seven to eleven, peace with SDG sixteen, and partnership with SDG seventeen [2].

The UN assembles an annual report since 2016, and this year contained the information of 163 countries with the advances of 94 indicators (plus one indicator for OECD countries) with normalized values between 0 and 100, qualified with a traffic light rank red, orange, yellow and green [3]. The SDG indexes are determined by the combination of the values of the indicators related to each SDG and are complemented with a tinted trend.

Some countries have published, within the last few years, their own reports for their internal use, with different geographical levels including cities, regions, and municipalities [10]. However, other reports alongside the global report are occasionally regional e.g., Arab, and Mediterranean or continental in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, and Europe [SDG Reports website].

For all the reasons explained above, it is therefore important to monitor the SDG indicators in the implementation of local planning, emphasizing the strengthening of local resilience to support the achievement of “Leave No One Behind” from the bottom-up perspective.

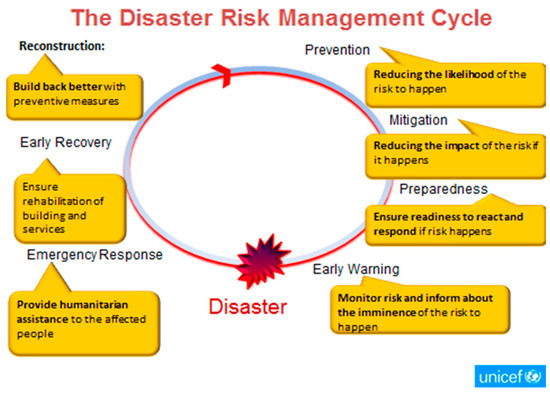

The disaster risk reduction framework (Figure 5) shows the tasks that can be organized and implemented by the different levels of government in developing countries in coordination with the national government during large emergencies.

Figure 5.

The cycle for disaster risk reduction.

The Sendai disaster risk reduction framework is an important complement to the SDG Agenda 2030, as it reinforces the importance to strengthen local resilience. The DRR framework states in the last sentences of its goal “… increase preparedness for response and recovery, and thus strengthen resilience”, and its priority for action number 3 is dedicated to investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience [10].

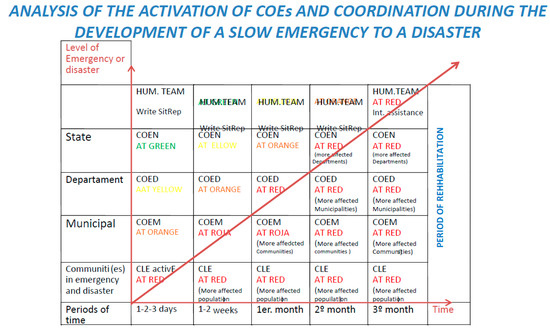

Hence, the DRR framework recommends strengthening the resilience to lower the disaster risks in developing countries at national, regional, and local levels. The tasks of preparation–response–early recovery in Figure 5 could be run by local governments because they are the first to respond with their Centre for Operation in Emergencies (COEs) as Figure 6 shows [11], and the national, and several regional governments should be in charge of the major tasks in prevention–mitigation–reconstruction.

Figure 6.

Escalated response in an emergency. F. Guachalla,2011.

It is of high priority to find new ways of working at local levels to strengthen local resilience, while the national governments build new policies for DRR to reach the poor and work together for a sustainable well-being.

3. Use of the PlaMSyL Method with SDGs and Resilience Indicators

Tools of PlaMSyL Method

The PlaMSyL method has two types of tools: the Static (SDB) and the Dynamic Data Bases (DDB).

The SDBs are used for planning: the project cycle, the geo-population list/map, the log-frame, the outcome mapping LF-tree, the timetable, the personnel chart for accountability purposes, and the Budget. Meanwhile, the DDB are three data matrixes: the field information, the calculation of indicators and the qualification of results [7].

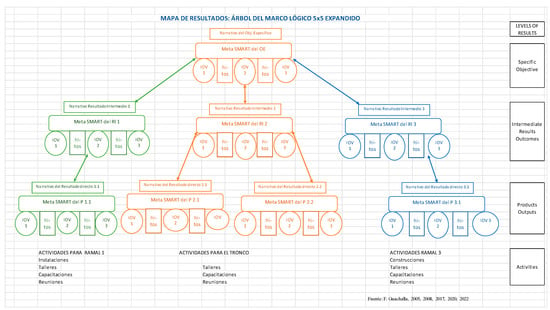

The scheme of the outcome mapping LF-Tree in Figure 7 shows the components of the specific objective (SO), the outcomes (IR), and outputs (P) with three elements: the narrative, the targets, and the indicators of the log-frame components (SO–IRs–P), plus the level of activities (As). This tool improves the coherence and consistency of the LF, emphasizing the learning pathways of the local actors, who contribute with their resilience to the sustainability of their development, showing with different colors, each outcome target group.

Figure 7.

Outline of the outcome Mapping LF-Tree. F. Guachalla, 2008.

The rest of the SDBs are well-known, but the method highlights the quality, accountability, and transparency of the programming.

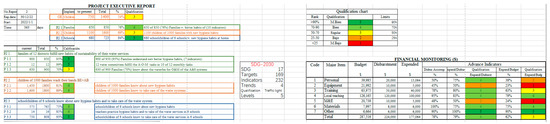

Scheme 1 shows a schema of the executive report that is calculated with the result indica tors that show the advances towards the targets and their qualifications with a five-rank traffic light according to the parameters of time and difference to the target [7].

Scheme 1.

Outline of the executive report dashboard.

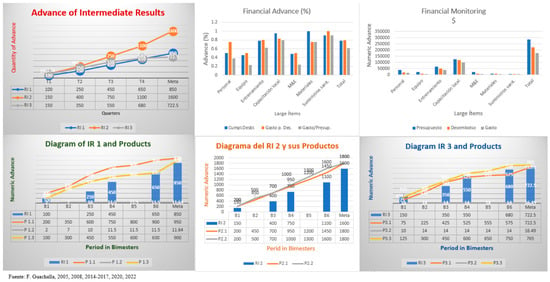

Figure 8 shows the systematization curves of the outcomes (IR 1, IR 2, and IR 3), the relation of each IR with its outputs P 1.1, P 2.1, P2.2, P 3.1, and so on, along with the financial monitoring curves for the completion of the report. The complete dashboard can be prepared in real-time.

Figure 8.

Sys-Curves of Outcomes (IRs) and Outputs (Ps), 2020.

4. Inclusion of SDG and Resilience Indicators

This practice has shown that indicators of the SDGs and of local resilience can be found or be included in the monitoring system of PlaMSyL. For example, in the WASH projects, one main indicator is # and % of population with clean water and hygiene practices, consistent with the first indicator of SDG six “population with clean water”, with its target of 100%.

One indicator of the project for strengthening local resilience was the # and % of community promotors (health, WASH, Teacher) that count with a plan for attention in emergency (PAE), and participate in a community simulation with the school, the families, and leaders in coordination with the local technical team. This is consistent with the recommendations of the Sendai framework. In SDG four, the main indicator is the # of schoolgirls and boys that finish primary and secondary school, where the indicator of resilience could be included.

Thus, the PlaMSyL method responds to the challenge of a dynamic, emergent, and complex context, and it includes SDGs 2030 as well as the resilience indicators monitored at local level with the participation of several actors and strengthening the local resilience towards a sustainable development. The method responds to the challenges of monitoring and learning with quality, accountability, and transparency, and has proved to be easy to use by the local technical teams, community committees, project teams, and other stakeholders.

Funding

I develop this method during the projects, without a specific funding for it.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. I developed the method while implementing development and emergency projects for Catholic Relief Services and UNICEF in partnership with other institutions like: International Plan, Caritas, other UN agencies, etc.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. The method was developed during the implementation of development and emergency projects.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation. In Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Resolution. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.; Lafortune, G.; Kroll, C.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. From Crisis to Sustainable Development. In The SDGs as Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond; Sustainable Development Report 2022; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UN Report. The Unfinished Agenda, Evaluation Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guachalla, F. Community, School and Municipal Development, 2nd ed.; Editorial Nuevo Siglo: La Paz, Bolivia, 2005; Available online: https://www.librarything.es/work/5811152 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Guachalla, F. Humanitarian Performance Monitoring Reports to UNICEF in the Philippines and Sierra Leone; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guachalla, F. Gerencia de Proyectos; Universidad La Salle: La Paz, Bolivia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hummelbrunner, R. Beyond logframe: Critique, Variations and Alternatives. In Beyond Logframe; Using System Concepts in Evaluation; Fujita, N., Ed.; FASID: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- French Gates, M. What Nonprofits Can Learn from Coca-Cola. 2010. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GlUS6KE67Vs&t=1s&pp=ygU7bWVsaW5kYSBmcmFuY2UgZ2F0ZXMgaW50ZXJ2aWV3IG9uIHByb2plY3QgZXZhbHVhdGlvbiBvbiB0ZWQ%3DTEDtalk (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations: Sendai, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guachalla, F. Strategy of Risk Management and Attention of Disasters in Bolivia; Strengthening Municipal Governments. Project Report to UNICEF; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).