1. Introduction

The elderly, compared to the general population, have an increased risk of suicide. According to the literature, COVID-19 may increase this risk due to guidelines and policies that impose social distancing and, consequently, the experience of loneliness. The pandemic exacerbated physical and psychological problems and denounced weaknesses in this population. The WHO [

1] pressured the need to be attentive to this relationship, to design prevention programmes, and to expand our attention to the associated risk factors, since the confluence of risk factors for suicide and suicide attempt is increased and may have a significantly high long-term exponent.

Statistics on suicide among the elderly point to higher rates in this population than in younger people [

1]; this data was confirmed by several authors [

2] who emphasized ages above 70 years as the most prevalent in almost all continents.

Nurses play an important role in identifying people at risk of suicide, which is why it is important to know the complex risk factors involved in suicide in the elderly as well as the interventions to be used in its prevention, since in this age group there is greater deliberation and planning of the act. Suicide attempts are often associated with depression, psychosis, and substance abuse in younger individuals, but in the elderly, depression and medical comorbidities play important factors [

3].

Some systematic reviews [

3,

4] have sought to identify best practice multilevel prevention strategies using the development of clinical skills in health professionals to recognize and treat depression and suicidal tendencies, institute adequate analgesia, improve the accessibility of care for people at risk and restrict access to means of suicide by betting on the literacy of the population and speaking openly about this problem.

Thus, the objectives of our study are to provide information in a systematized and quick-reference manner and to support decision-making in assessing the risk of suicide in the elderly.

2. Material and Methods

Supported by a literature review with data collected from the Scopus and Web of Science databases, we used the PICO components (Adults ≥ 60 years as the target population; any type of intervention to prevent or reduce suicidal behaviour; including behaviours of suicide, suicidal ideation or attempt), and the descriptors ‘elderly or old aged’ and ‘suicide’ and ‘prevention programs’ and ‘review’ and ‘nursing’, in a total of 9 articles. A flowchart was prepared to support decision-making in nursing within the scope of assessment of suicide risk in the elderly and nursing interventions to be developed. The search limits included English language articles and full text. Two independent reviewers extracted the data.

3. Results

The studies highlight the impact of COVID-19 on the worsening risk of suicide and mental illness [

5].

Some mental health appointments and prescriptions were postponed, and others were cancelled when considered ‘non-essential’. Attendance at consultations was hampered by interruptions or the fear of the elderly to travel by public transport with advice to stay at home, and the media’s focus on emergency medical care also being another of the factors that hindered the management of psychiatric illness in the community [

4].

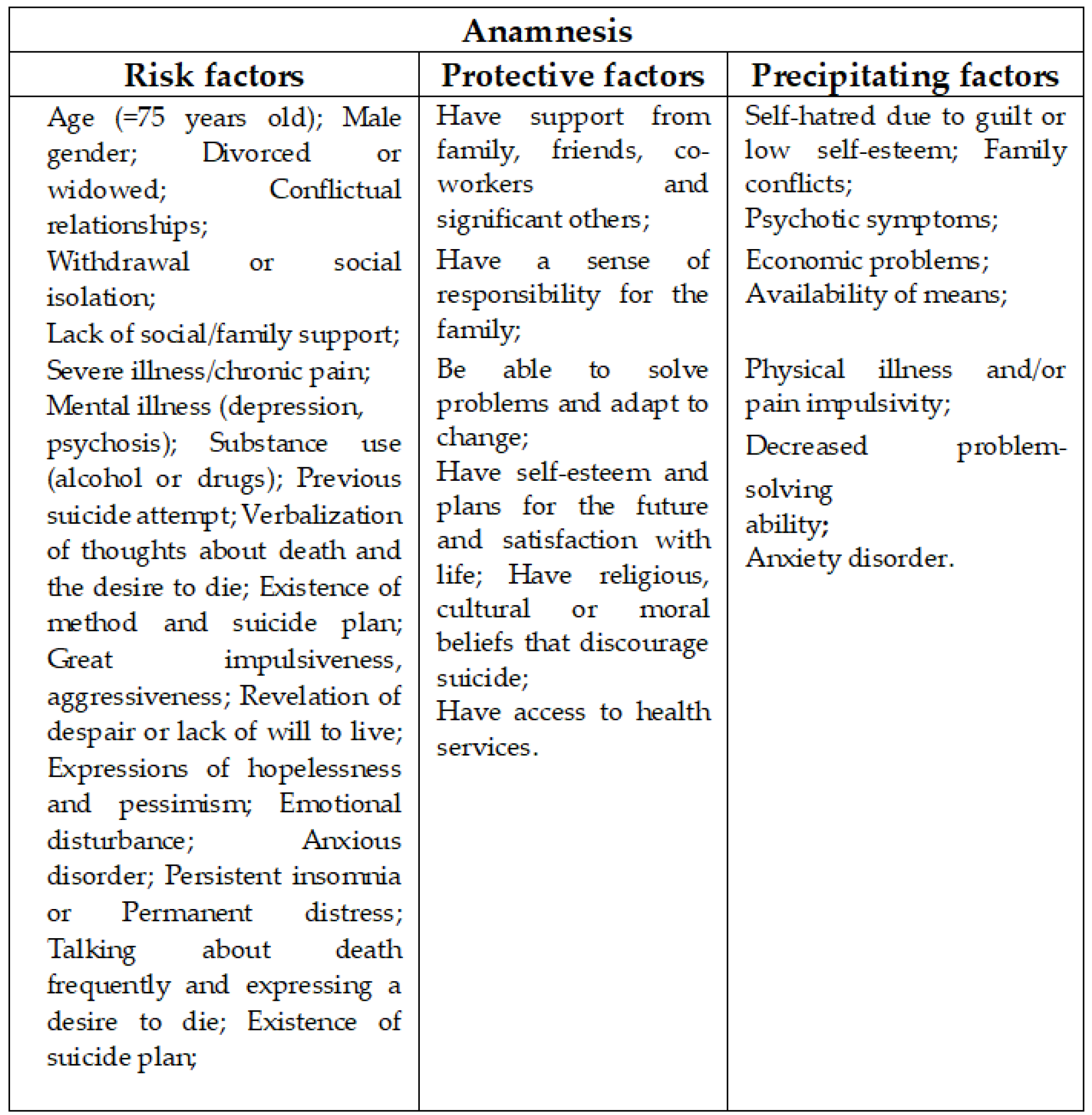

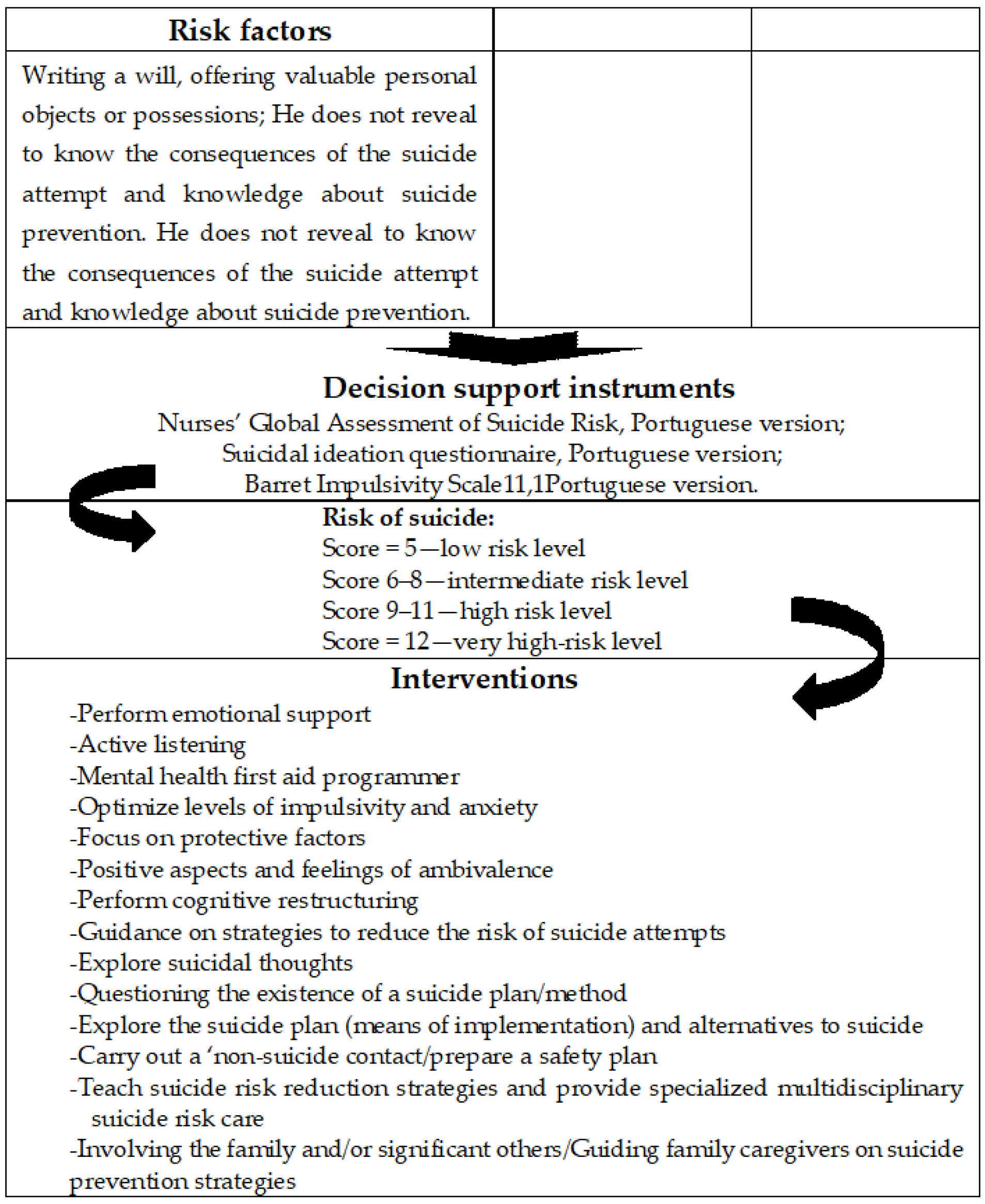

The model developed in the flowchart is divided into three phases: the client’s anamnesis (identification of risk, precipitating and protective factors as shown in

Figure 1), the risk analysis is carried out and, consequently, the interventions according to the weighted risk.

In this perspective, the flowchart guides the collection of data and the choice of instruments to support decision-making in risk analysis, systematizing the nursing intervention with a view to improving the quality of the process and the results.

In the development of the flowchart, we incorporated the contributions of the programmes analysed in the literature review [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], considering the phase and context of the application, which best suits the objectives we intend to achieve.

4. Discussion

Flowcharts allow you to draw a picture of how a process works, making it easier to understand. They show how to document, plan, improve and communicate often complex processes with clear, graphical representations that everyone in the healthcare team can understand. It is beneficial for everyone involved in the clinical journey to see how the steps are connected to each other through a visual representation, making it possible to improve efficiency in care, as it provides information about the entire process, improving communication and documentation.

Most studies [

3,

4] were centred on the reduction of risk factors (depression screening and treatment and decreasing isolation). In fact, there is a lack of basic knowledge and training about elderly suicide among clinicians.

5. Conclusions

It is expected that the effect of the pandemic on the elderly will be reflected in new cases of mental disorders, greater intensity of symptoms, greater obstacles in accessing timely treatment and a decrease in community service responses. Furthermore, it is believed that an increase in distress, relapse and suicide risk consequently occurs [

5].

The literature has been pointing to the importance of guidelines, educational material for professionals and the general public as well as the existence of professionals specialized in supporting situations of isolation. Approximately 90% of suicide cases are associated with mental illness [

1], which is why it is appropriate to develop a flowchart to guide nurses in assessing the risk of suicide in the elderly when taking clients’ anamnesis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O., J.O. and J.M.; methodology, E.O. and J.O.; data collection, E.O.; data analysis, E.O. and J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, E.O. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by National Funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020 and reference UIDP/4255/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is based on the review of studies and does not include participants.

Informed Consent Statement

This requirement is not applicable to this type of study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112738 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Sousa, G.S.d.; Perrelli, J.G.A.; Botelho, E.S. Nursing diagnosis for Risk of Suicide in elderly: Integrative review. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2018, 39, e20170120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Sarchiapone, M.; Postuvan, V.; Volker, D.; Roskar, S.; Grum, A.T.; Carli, V.; McDaid, D.; O’Connor, R.; Maxwell, M.; et al. Best Practice Elements of Multilevel Suicide Prevention Strategies. Crisis 2011, 32, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalsman, G.; Hawton, K.; Wasserman, D.; van Heeringen, K.; Arensman, E.; Sarchiapone, M.; Carli, V.; Höschl, C.; Barzilay, R.; Balazs, J.; et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Chen, J.-H.; Xu, Y.-F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeira, C.; Sampaio, F. Enfermagem em Saúde Mental: Diagnósticos e Intervenções; Lidel—Edições Técnicas, Lda: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DGS. Programa Nacional para a Saúde Mental. Plano Nacional de Prevenção do Suicido 2013/2017. Available online: http://www.nocs.pt/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Plano-Nacional-Prevencao-Suicidio-2013-2017.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Galdeano, L.E.; Rossi, L.A.; Zago, M.M.F. Roteiro instrucional para a elaboração de um estudo de caso clínico. Rev. Latino Am. Enfermagem. 2003, 11, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.P. Guia orientador de boas práticas para a prevenção de sintomatologia depressiva e comportamentos da esfera suicidária; Ordem dos Enfermeiros: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-K. Major Depressive Disorder: Risk Factors, Characteristics and Treatment Options; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Façanha, J.; Santos, J.C.; Cutcliffe, J. Assessment of Suicide Risk: Validation of the Nurses’ Global Assessment of Suicide Risk Index for the Portuguese Population. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016, 30, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).