1. Introduction

The rapid development of Photovoltaic (PV) technology has played a pivotal role in the global transition toward sustainable and low-carbon energy systems. Global cumulative PV capacity had exceeded 2.2 TW (2024), representing a year-on-year increase of approximately 37.5% from 2023 [

1,

2,

3]. This exponential growth highlights the increasing dependency on solar energy as a pivotal element in global decarbonization strategies. However, the expansion of PV infrastructure is increasingly due to the competition/scarcity of suitable land, particularly in densely populated or agriculturally valuable regions. This brings an increase in interest in alternative deployment models, and Floating Photovoltaic (FPV) systems are one of the promising solutions [

4].

FPV systems involve the installation of PV modules on floating platforms on water bodies, such as lakes, reservoirs, ponds, and decommissioned quarries. This innovative approach offers several benefits. First, it helps preserve land for agriculture, habitation, or natural ecosystems, thus mitigating the land-use conflicts often frequently associated with Ground PV (GPV) systems [

5]. Second, the proximity to water has been demonstrated to have a cooling effect on PV modules, improving their efficiency and total energy output by lowering their operating temperature. It has been observed that this could improve the electrical conversion efficiency of PV modules by 10–15%, depending on climatic conditions and system configuration [

6]. Furthermore, the water coverage provided by the floating modules can significantly reduce evaporation rates, and this results in valuable advantages in arid regions where water preservation is critical [

4].

Despite these benefits, large-scale FPV deployment introduces several environmental and technical challenges that must be addressed to ensure long-term sustainability. One of the primary issues involves the impact of FPVs on aquatic ecosystems. The shading caused by the modules can reduce light penetration, altering photosynthetic activity and potentially suppressing native aquatic vegetation. Wind dynamics and surface temperature stratification may also be affected, disrupting the natural thermodynamic equilibrium of the water body. Such alterations can influence key environmental parameters, including water temperature profiles, Dissolved Oxygen (DO) concentrations, and pH, and can change nutrient dynamics [

7]. In some cases, these alterations may encourage algal blooms or may negatively affect fish populations and other aquatic organisms [

8]. Moreover, the persistent presence of plastic and metallic materials in FPV platforms—commonly High-Density PolyEthylene (HDPE), but also aluminum or steel—raises issues about both material degradation and potential release of contaminants into the water, even though empirical data concerning these risks remains still limited [

9,

10].

Conventional water quality monitoring techniques, which rely on manual sampling and subsequent laboratory analyses, are generally constrained by limited spatial and temporal resolution and often result in significant logistical costs.

The use of autonomous or remotely operated vehicles, encompassing aerial and aquatic, could substantially reduce costs outside the structure, improving safety, even if the aerial vehicles are facing sunlight reflections or having glittering issues, which can affect image quality acquisition [

11].

To address these limitations, recent research has turned toward the integration of autonomous robotic systems for environmental data collection [e.g., robotic boats or Autonomous Surface Vehicles (ASVs), or, more in general, Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs)] [

12]. Several studies [

13,

14,

15] have successfully demonstrated how these systems can be employed as effective platforms for the real-time monitoring of water quality parameters such as temperature, turbidity, pH, electrical conductivity, and DO, and for detecting the presence of nutrients or pollutants [

16,

17,

18]. These vehicles can be equipped with high-precision multi-parameter probes, Global Positioning Systems (GPSs), Inertial Navigation Systems (INSs), and wireless communication modules, thereby enabling spatially distributed measurements across large water surfaces with minimal human intervention. The modular design of many ASVs allows for the integration of a wide range of sensors tailored to specific monitoring needs, including spectrophotometric, fluorometric, and electrochemical sensors [

19,

20].

Recent advancements in control algorithms and energy-efficient propulsion systems have significantly improved USV autonomy and endurance, making them suitable for long-duration missions (several hours) in remote or complex and dynamic marine environments [

21]. Several platforms are characterized by adaptive path-planning and obstacle-avoidance capabilities [

22]. These innovations can be particularly valuable in FPV installations, where the complexity and the wide variety of layouts, combined with the presence of obstacles and mooring systems, need precise navigation for inspection and data collection purposes.

In addition to the environmental monitoring task, ASVs can be equipped with thermal cameras, high-resolution imaging systems, and sonar devices to perform structural inspections and performance assessments of FPV. These capabilities are essential for the early diagnosis of defects such as module misalignment, cable detachment, or flotation anomalies.

It should be noted that an ASV/USV can normally stay out of the water (e.g., in a boathouse), so all sorts of monitoring activity can be scheduled to minimize environmental impact on the site, even if, as referenced in

Section 3, the degradation of the vessel is, in any case, extremely low and insignificant with respect to the overall FPV infrastructure issues discussed in this work (see

Section 6). In addition, an autonomous vehicle can be moved where needed, keeping specialized personnel free from routine and intensive tasks.

The economic impact of FPV Operation and Maintenance (O&M) remains under significant investigation. Although the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) of FPVs is generally competitive with GPV systems, deep uncertainties persist regarding long-term maintenance expenses and the potential need for specialized personnel and equipment. Integration of autonomous monitoring on inspection platforms is expected to play a key role in mitigating these costs and encouraging the feasibility of FPV installations.

In this context, ASVs represent a critical enabling technology for FPV expansion, providing real-time ecosystem health monitoring and predictive maintenance, and supporting actions related to solar infrastructure management.

In this paper, we introduce a low-cost robotic boat capable of a dual operating mode, either autonomously (ASV mode) or under operator control (USV mode).

2. FPV System Issues and Their O&M

A typical FPV plant is complex, and it does not have a standard layout; one of the few things it often has in common with GPV is its modules, which lie at a fixed tilt and azimuth angles oriented toward the sun. These modules are often placed on individual floats, which are subsequently interconnected. In other projects, they are placed on a larger single floating pontoon.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, a walkway is normally designed to facilitate maintenance activities.

Low-voltage transformers can be placed onshore for smaller plants (or ow voltage/medium voltage part of the way in larger ones), but in most cases, they are located on the floating array, usually on special floats with extra buoyancy.

Cables conduct electricity from the transformer to the substation (normally located near the grid). These cables can be floating on the water surface or can be resting underwater.

Consequentially, the O&M tasks for FPV systems encompass both a combination of routine (preventive and corrective) maintenance activities and continuous monitoring and predictive operations. Streamlined O&M practices are indispensable to ensure the long-term performance, reliability, safety, and environmental sustainability of these systems, through a twofold mission: (i) efficient mitigation of potential technical risks (hence, downtime), and (ii) maximization of the long-term PV energy yield, with a direct positive impact on LCOE and the payback time [

24].

The primary challenges associated with O&M FPV systems can be outlined as follows:

Addressing additional risks associated with the water-based working environment.

Providing safe and cost-effective access to the floating platform (inherently more complex, risky, and time-consuming than GPV access).

Ensuring accessibility and reachability for all maintenance activities across all components. Establishing clear requirements for cleaning and maintenance, such as poor accessibility (this may lead to an increase in the number of persons per hour) or potentially increasing downtime.

Maintaining the long-term performance, stability, and safety of FPV installations, which depends on diligent and comprehensive inspection protocols covering all key components.

In order to pursue these objectives, it is necessary to inspect:

Anchoring/Mooring Systems: As a consequence of their crucial role both for the stability of the FPV system and for mitigating mechanical stresses from environmental forces like wind and waves, it is imperative to carry out rigorous inspection of the anchoring and mooring systems, so FPV asset managers have to implement a dedicated O&M plan that encompasses inspections, along with maintenance and spare parts management. Regular inspections are mandatory, carried out in a proactive manner, to identify issues such as wear, fatigue, corrosion, marine growth, biofouling, and any other form of degradation or damage. Such inspections are typically visual and often carried out by specialized personnel (divers) or Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs). In the mooring line context, continuous integrity checks and tension measurements are imperative. Anchor inspections, on the other hand, are crucial to identifying any physical degradation of the anchor itself or in the connection points.

Floats: In a similar manner, buoyancy inspections are a critical issue for the O&M of FPV systems. The purposes of these activities are to identify any sign of leaks, wear, gashes, fatigue, or failure in the floating platforms. This enables the stability, safety, and longevity of the entire floating structure. Just like anchoring/mooring, more intensive inspections are vital for critical float components, especially after an extreme weather event. These inspections are essential for the early detection of potential damage, including but not limited to punctures, cracks, loss of buoyancy or stability, loosening of connection pins, and corrosion of metallic parts.

FPV Arrays: Finally, a comprehensive acknowledged inspection of the FPV arrays represents an indispensable element for FPV O&M. Aligning with standards such as IEC 62446-1 [

25], IEC 62446-2 [

26], and IEC TS 62446-3 [

27], these inspections extend beyond identifying common PV failures. All possible adoptable sensors for inspection make it particularly critical to detect and track degradation mechanisms. Both aspects are exacerbated by the marine environment, like corrosion, moisture ingress, and UV degradation. Moreover, considering the often-limited accessibility of FPV arrays, the use of remote sensing/unmanned vehicle technologies becomes not merely advantageous but also frequently indispensable for effective inspection.

Now we will consider some possible layouts for FPV systems.

Normally, an FPV system has a high surface density to decrease the cost of the floating structure per unit of PV power installed. An example of a common dense FPV is reported in

Figure 2.

A boat should be employed with restrictions or along the sides of this type of plant.

Some other FPV solutions are based on tracking systems, especially when the power density is lower but the energy density is higher.

Figure 3 shows a floating PV system proposed by Flotus©, with a Horizontal Axis Tracker (HAT). The FLOTUS© prototype has been installed with both monofacial and bifacial PV modules to better understand the influence of the module technologies installed on this innovative platform, facilitating a more comprehensive impact analysis of those PV modules on a larger HAT-FPV system. Using a boat might facilitate these studies.

Another solution has been proposed by Xfloat© (see

Figure 4): The distance between rows typically ranges from 1.95 m to 2.35 m. This variation is related to the PV module size employed. Rows are connected by rails. It is estimated that a vessel measuring approximately 1 m in width and 2 m in length should be able to navigate these distances without any issue. In fact, the rail depth connecting rows allows for free small boat movement.

Furthermore, there are other floating systems under development based on vertical bifacial modules such as the one proposed by Sinn Power [

31]; see

Figure 5.

Also in this case, a boat would be necessary for the effective operation of the plant.

Given the variety of FPV system configurations, it is evident that a single vehicle cannot cover all operational situations. Nevertheless, such a system could benefit from the support provided by an ASV/USV.

The proposed platform has the potential to provide a solid basis for future developments and adaptations. In this contribution, we present an autonomous boat, with dimensions that can be further reduced due to its scalable electronics, that is able to operate in particularly cramped contexts. PV system status monitoring can be carried out through multi-spectral and thermal imaging cameras to detect anomalies in the PV modules. Such anomalies may include temperature variations related to hot spots on PV modules, electrical faults, or accumulation of dirt. Finally, the use of acoustic and optical sensors aboard the boat could facilitate the structural analysis of floating components, identifying potential deformations/displacements or possible damage to panel supports.

It should be noted that, although the analysis presented in this paper focuses on USVs, it is important to highlight that similar technological and operational principles apply to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). The functionality of both platforms encompasses the facilitation of autonomous and remote sensing operations inside environments that are difficult or unsafe for human intervention. UAVs can provide rapid and high-resolution visual and/or multispectral mapping of the FPV plants as regards surface, structural components, and surrounding area. The flexibility of these systems enables frequent surveys and large-area coverage; however, some limitations persist with respect to flight endurance, payload capacity, and weather sensitivity. Conversely, USVs offer persistent, close-range monitoring directly on the water surface, enabling the collection of hydrological and environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, turbidity, conductivity) as well as the mechanical inspection of floating structures. The complementary nature of these two platforms suggests that an integrated USV–UAV approach [

32] could significantly enhance the efficiency and robustness of maintenance and environmental assessment operations for FPV installations.

3. The Vehicle: Hardware and Software

The boat hull employed for the ASV under discussion in this work is made of high-rate low-maintenance polyethylene [

33] and consists of a 210 cm long double shell with high lateral shores to protect the equipment from the water jets (see

Figure 6).

One of the strengths of the robotic boat described in this paper is its cheaper construction and management. In the past, we have dealt with structured materials [

34,

35,

36], granular materials [

37], and meta-materials in general [

38]. These materials are used for high-performance vehicles, which are not the subject of this paper. However, expertise in such materials can support the development of innovative monitoring solutions for FPV systems and could be a subject of future work.

The design of the robotic boat involves two different motor configurations: two propellers and four propellers.

In the two-thruster configuration, the pair is mounted perpendicular to the thruster frame on the stern; the variation in relative thrust between the two allows for turning maneuvers.

In the four-thruster configuration, on the other hand, each motor is inclined by 45° and equally spaced (as the vertices of a square), two towards the bow and two at the stern, by means of a specific bridge; this stratagem allows for lateral translational maneuvers, ensuring greater precision in movements and control improvement.

The propellers used in both vehicle versions are submarine thrusters originally designed for underwater drones. They are robust and efficient low-maintenance units designed to operate in critical marine environments, ensuring reliability and high performance. Each motor can generate up to 51 N of thrust and uses a fully flooded three-phase brushless motor with encapsulated windings and stator. This architecture allows for direct water cooling and passive lubrication of the plastic bushings, eliminating the need for expensive magnetic couplings or sealed compartments filled with oil or air, thus also eliminating pollution risk.

The thruster body and propeller are made of polycarbonate, while the few exposed metal components are designed to resist marine corrosion, lowering the toxicity risk.

The thrust is managed by an Electronic Speed Controller (ESC), which allows for fine and responsive control of the thruster, and is adaptable in real time to the different operating conditions of the vehicle.

Note that the results presented in this paper are relative to the first configuration only.

The control module consists of Pixhawk 4 [

39], an advanced autopilot developed for autonomous robotic systems in general. Designed to offer high performance and reliability, it integrates a 32-bit STM32F765 microcontroller with a clock frequency of up to 216 MHz, ensuring adequate processing capacity.

The Pixhawk 4 is equipped with a comprehensive set of integrated sensors, including gyroscopes, accelerometers, and magnetometers (INS), which are critical for providing inertial data for attitude control, vehicle stabilization, and navigation, and complemented by a series of configurable I/O (input/output) ports, which allow for flexibility in interfacing external additional devices and sensors.

The Pixhawk 4 is compatible with two widespread firmwares, such as PX4 [

40] and ArduPilot [

41], and supports expansion with numerous add-on modules, making it suitable for a wide range of robotic and autonomous applications.

In our project, the Pixhawk was connected to a RaspBerry Pi [

42]. Combining both electronics offers high processing power and a wide range of functionalities that can be fused for different purposes, enabling the vehicle to increase its overall processing power. Some examples are parameterizing mission planning, image processing, data analysis at a more computationally intensive level, and other tasks, such as obstacle avoidance, object recognition, and, more generally, other computationally intensive tasks. The Raspberry (or any other generic Single-Board Computer—SBC) could also be configured to connect and manage additional sensors that are not directly compatible or supported by Pixhawk—for example, high-resolution cameras, vision sensors, environmental sensors, data communication systems connected to external databases, etc. The Pixhawk and Raspberry Pi can communicate via several serial buses, such as UART, I2C, or SPI. This communication enables the synergistically continuous exchange of data and commands among them. Real-time data exchange or remote-control operations of the system from the Ground Control Station (GCS) can be realized with a suitable radio network.

The software working on GCS is the QgroundControl (QGC) application [

43], maintained by the Dronecode© Foundation. It is an open-source software designed primarily to manage Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPAs), based on PX4 or ArduPilot autopilots. QGC provides an intuitive user interface that connects to the vehicle’s onboard autopilot and/or the ground pilot via a telemetry link, allowing GCS users to interact with the vehicle in multiple ways, including real-time monitoring of system status and onboard sensors, manual control, mission plan, and modification of a wide range of configuration parameters (over 800). In addition, it collects and displays detailed vehicle telemetry data, facilitating post-mission analysis and diagnostics.

QGC uses modular architecture to manage vehicle communication. It takes advantage of standard communication protocols such as MAVLink [

44] for two-way communication; this enables the vehicle to carry out data transmission (e.g., telemetry) and real-time data streaming (e.g., video). The QGC user interface is designed to manage multiple vehicles and systems simultaneously.

In

Figure 6, the unmanned boat in the two-thruster configuration is shown during its first navigation test on Bracciano Lake, 30 km north of Rome, Italy.

In

Table 1, some of the mechanical and electrical characteristics of the robotic boat are summarized.

The two-engine version, as shown in

Figure 7, is visually described via a diagram and a schematic block, depicting all set of devices that manage and operate the ASV. The equipment aboard consists of two main boxes (electronics and batteries) that follow the connection diagram of

Figure 8. The first box contains drivers, control units, receivers, and all the electronic boards in general that are useful for the operation of the vehicle; the second, on the other hand, contains all the batteries, both the main one that powers the Motors via the Driver board (MD in

Figure 7) inside the electronic box and service batteries, essential to energizing all the rest of the electronics and useful for the complete operation capacity of the ASV.

The system is completed with a 2.4 GHz transceiver (shown in

Figure 7b—RC-RX) to interconnect the electronic box with the ground-based operator radio remote controller and a telemetry module (shown in

Figure 7b—TELE_TX), operating at the license-free frequency of 434 MHz to complete the link between the robot and GCS. So far, the vehicle is not yet equipped with sensors for measuring water quality or monitoring FPV parameters.

Figure 8 shows other images taken during the assembly of the vehicle.

4. Lake Trials

The validation tests were prepared with numerous lake trusts (Bracciano lake), preceded also by several experiments in the laboratory pool.

The open water tests involved a long period of time for the PID control parameter calibration (PID stands for a combination of controller coefficients: Proportional, Integrative and Derivative). Typically, the proportional gain adjustment (P) serves to improve responsiveness; however, an excessive gain value can trigger oscillations. The Derivative term (D) helps dampen oscillations, while the Integral term (I) corrects persistent errors in attitude control; a too-low value leads to drift over time, and this increases positioning error. Naturally, these parameters have been adjusted for each set of controls and through subsequent refinement procedures to reach the desired trajectory.

In

Figure 9, there is a field-acquired example of bad (

Figure 9a) and good (

Figure 9b) adjustment of the control PID parameters; it is evident how this affects the trajectory of the robot. The orange line is the set trajectory, while the red line is the one followed by the robot. The sides of the quadrilateral are approximately 50 m long.

Figure 9c,d show a robot boat journey on Bracciano lake.

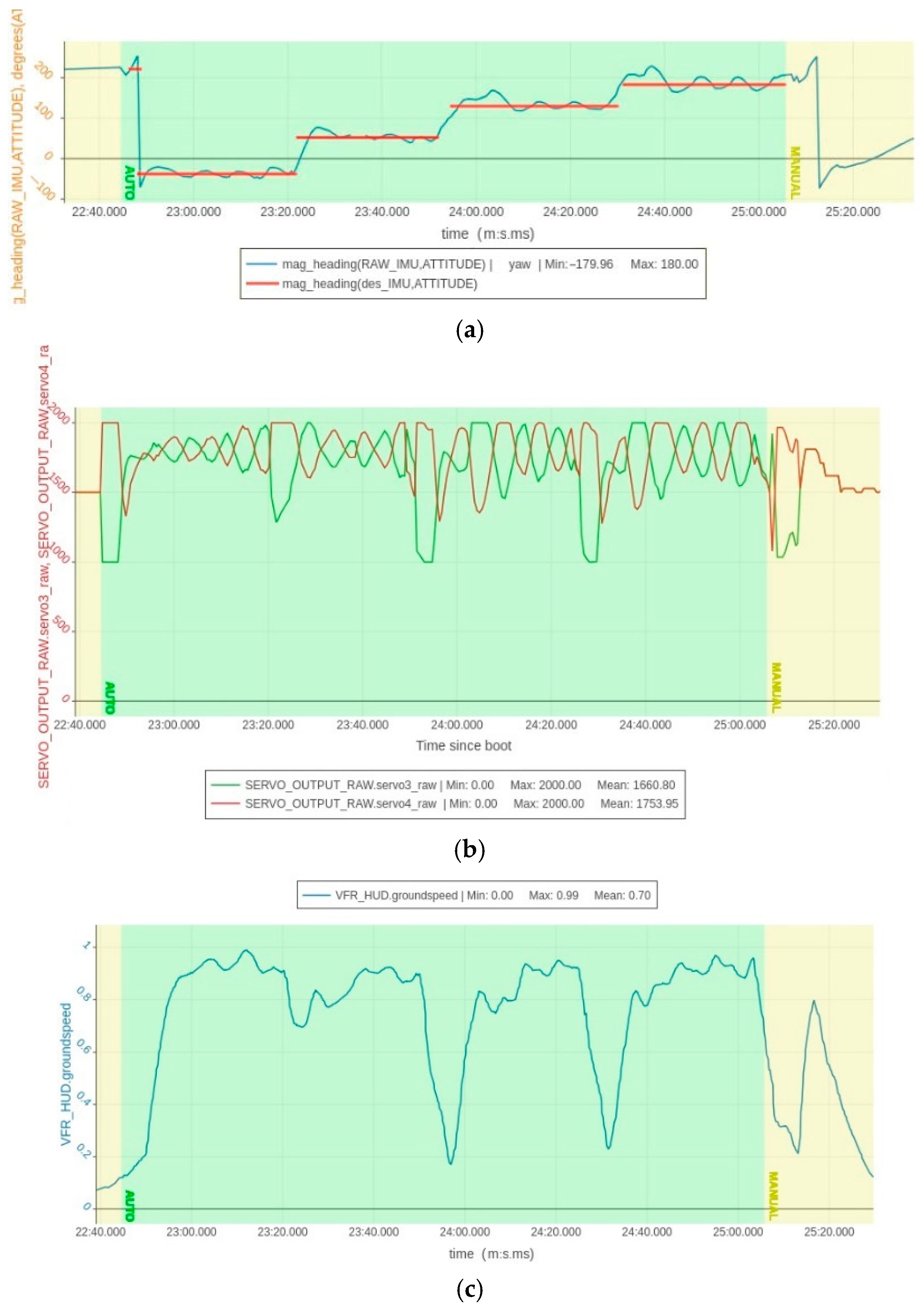

Figure 10a–c show the waypoint-related data for the trajectory illustrated in

Figure 10b, compared to the desired reference values. Specifically, they present the vehicle’s heading (

Figure 10a), the thruster power output used to reach waypoints (

Figure 10b), and the vehicle’s speed throughout a mission (

Figure 10c).

It is worth noting that, during testing (see

Figure 8), the motor support frame was intentionally left in a simplified and non-optimized configuration to deliberately increase the level of disturbance. This was done both to stress the calibration and to evaluate the control system robustness. The platform demonstrated a high degree of flexibility and excellent maneuvering capabilities, even in its simplest two-thruster configuration. The motors exhibited satisfactory performance under load conditions of up to approximately 150 kg. During testing, the vehicle was able to dynamically compensate for imbalances caused by the movement of two onboard operators.

5. Obstacle Avoidance

In this section, we aim to describe an image segmentation system usable in a semi-automated water vehicle capable of discrimination between regions with water from those without it, generating binary masks. The analysis of each mask makes it possible to determine the position of the water line, an essential piece of information for obstacle detection.

The detection of the water line within the images captured by a camera represents a significant challenge due to the continuous movements of the vehicle (roll, pitch, and yaw), as well as the presence of light reflections, variations in lighting conditions (related to the position of the sun), and disturbances due to wave morphology.

Considering the difficulties mentioned above, it was deemed appropriate to investigate and apply techniques based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

45], which, as reported in scientific literature, have demonstrated good performance in this specific context. In particular, the work conducted is based on Ref. [

46].

In this first phase, the study focused on reviewing the methodology presented in the reference work, adapting the prototype code provided by the authors. The code was adapted and optimized to ensure compatibility with the latest software libraries and to guarantee reliable performance on modern informatics platforms.

The training of the U-net [

47], in particular, was performed using public datasets provided by the European project INTCATCH [

48], containing images of floating obstacles such as buoys, sailing, and motorboats, as well as dynamic elements such as swans in the vicinity of the autonomous vehicle. Subsequently, to assess the generalization capability of the neural network models pre-trained by the authors of the reference article, a test set consisting of frames acquired in Bracciano Lake was used by an action camera, as shown in

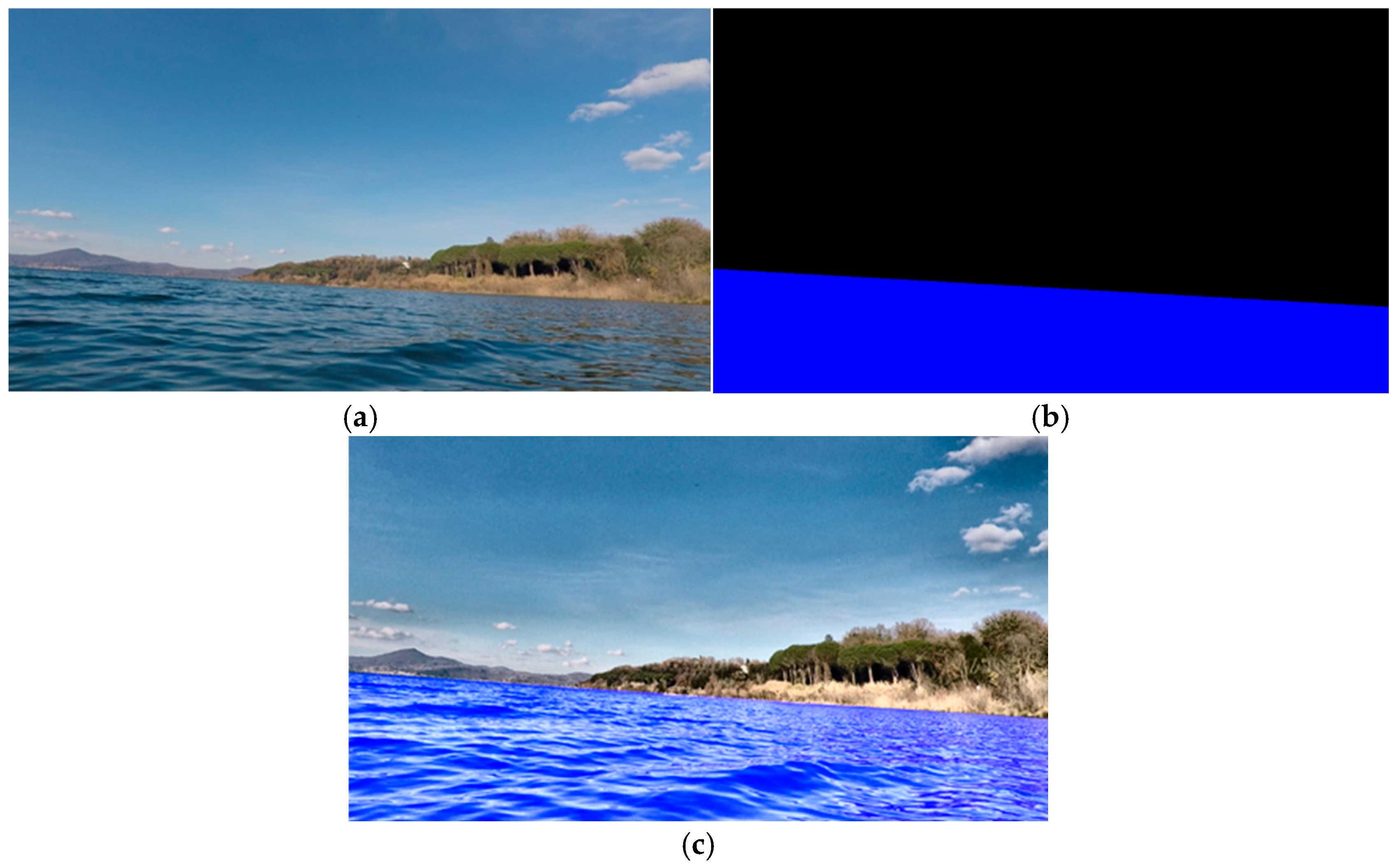

Figure 11.

Following the first phase, a detailed examination of the original training datasets was carried out. The analysis considered dataset structure (image resolution, labeling format, and class balance), preprocessing procedures (normalization and data augmentation), and scenario characteristics, with particular attention to environmental and lighting conditions. The objective was to evaluate their suitability for offshore ASV applications, where low-horizon inclination angles and challenging illumination effects, such as backlighting and specular reflections on the water surface, are common.

To build a tailored dataset, a dedicated computer-aided annotation tool was developed to streamline image labeling and cataloging. The adopted strategy (

Figure 12a–c) required selecting two points along the waterline in each image, defining a trapezoidal region corresponding to the water surface. This approach enabled semi-automated generation of ground truth masks for semantic segmentation.

After constructing the dataset, the predictive performance of a pretrained CNN was evaluated on a newly assembled test set and compared with results obtained using the original dataset from the reference study. The experiments confirmed the limitations mentioned above, underscoring the necessity of training on a customized dataset better suited to the ASV’s specific operating conditions.

Quantitative evaluation was performed too, using standard pixel-based classification metrics, namely recall, specificity, precision, accuracy, and F1-score, as reported in

Table 2. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the CNN’s discriminative capabilities, with particular emphasis on the trade-off between false positives and false negatives [

49,

50].

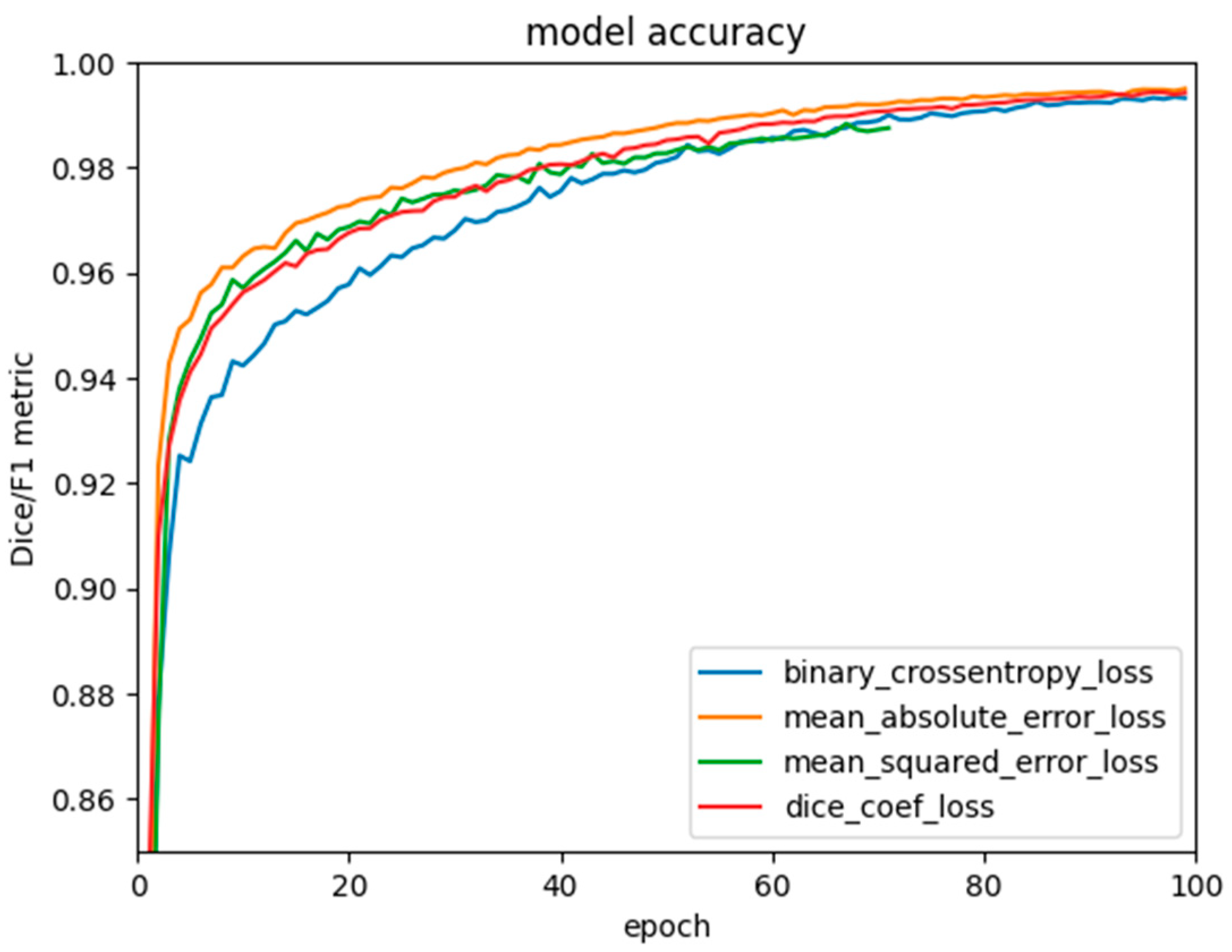

Figure 13 illustrates the evolution of the Dice/F1 metric over 100 training epochs for CNN models trained with different loss functions. All models showed improvements in segmentation accuracy, reaching final Dice coefficients close to 0.99. Among the tested loss functions, Dice and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) achieved faster convergence and maintained higher accuracy throughout training. Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) exhibited the slowest convergence, though it eventually achieved comparable final performance. Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss demonstrated intermediate behavior, outperforming BCE but remaining slightly below. Overall, Dice and MAE losses are more effective for stable and rapid CNN convergence.

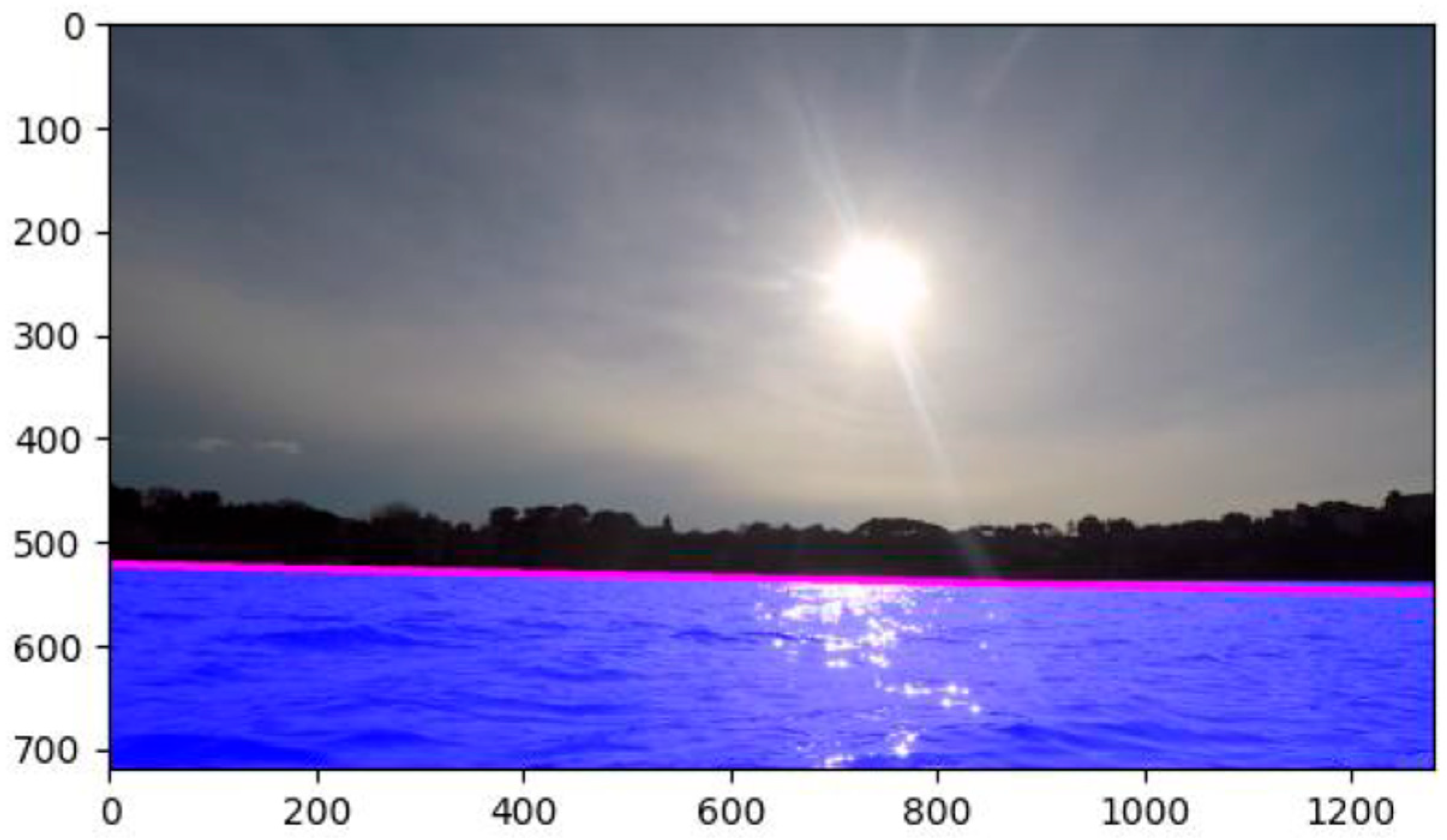

The work performed represents the initial phase of the obstacle detection process. Once the segmentation of the images has been completed, the next step is the identification of the waterline using the RANSAC algorithm [

51], which allows the waterline to be drawn on the segmented images, as can be seen in

Figure 14. After defining the waterline, the trained CNN will be able to identify obstacles such as buoys, swans and boats, monitoring their position frame by frame. In case of excessive proximity between the ASV and an obstacle, the control system will be able to stop the vehicle to replan the trajectory or to wait for the obstacle to move away according to the situation.

The replanning will be the object of future work, depending on variable strategies achievable plant by plant.

6. FPV Systems: O&M, R&D Challenges, and Societal Impact Highlights

Although this study primarily addresses the technical feasibility of employing low-cost USVs for the O&M on FPV systems, it also highlights the need for a broader socio-economic evaluation. Future development of this work should include an economic feasibility analysis based on the full life-cycle costs of USV development, operation, and maintenance, comparing these tasks with conventional manual inspection and monitoring methods. At the state of the art, the operating cost of the proposed USV is significantly negligeable with respect to the total cost of creating an FPV plant. FPV technology introduces unique O&M challenges and necessitates a broader evaluation of its societal and environmental consequences. All these aspects must be adequately exploited to let such solutions be largely adopted in the energy mix scenario. In several countries, adequate methodologies are still under development, driven by a lack of large and consistent field data to provide consistent assessment studies.

Current literature on FPV is limited, with a notable absence of a comprehensive breakdown of O&M costs and analysis, mainly due to both the limited availability of field data and different technological solutions in various operating and changeable conditions.

(1) O&M Cost Analysis

Few studies have discussed and compared the O&M costs of FPV systems to Ground-mounted PV (GPV) systems (see section VI-B of [

11]).

The estimated O&M costs in the literature suggest that the cost for FPV systems is highly site-dependent and can be either higher or lower, compared to GPV systems (as summarized in [

24], Table XII).

The 2025 IEA report [

52] provides a preliminary failure mode and effects analysis of technical and operational challenges and their impact on O&M, along with a list of key aspects for budgeting FPV O&M projects.

(2) Monitoring and Instrumentation

Unlike GPV, for which instrumentation requirements are standardized in IEC 61724-1 [

53] (including accuracy and number, according to plant size), no current standards describe the recommended sensors and procedures for FPV power plant monitoring.

FPV systems require the monitoring of additional variables compared to ground systems, as reported in

Table 3.

FPV technology faces specific R&D challenges, particularly related to scaling up installations and expanding offshore projects:

(1) Expert Dependence: The complexity of FPV requires specialized experts (e.g., divers, marine engineers) for maintenance and inspections, which increases costs and time. Potential solutions include AI-driven data analytics, UAV-based inspections, and autonomous systems to reduce human intervention.

(2) Extreme Weather and Degradation: Marine environments introduce severe stressors such as corrosion and UV exposure, which can accelerate FPV component degradation. R&D in advanced materials, protective designs, and robust emergency-response plans are crucial for improving durability.

(3) Monitoring and Remote Sensing: Remote FPV sites, especially offshore, struggle with data transmission reliability and high communication costs. Advanced solutions utilizing drones and satellites can significatively enhance monitoring and potentially reduce O&M costs.

Environmental Impact and Regulations: Concerns regarding FPV effects on aquatic ecosystems (water quality, habitat shading) necessitate eco-friendly designs and regulatory standards that adapt O&M practices for sustainability.

Environmental Impact and Sustainability Assessment

Evaluating the sustainability of FPV requires moving beyond energy yield and cost to encompass its life-cycle impacts and environmental effects.

The synthesis in Ref. [

54] demonstrates that FPVs reshape aquatic environments by altering light fields, evaporation, stratification, and dissolved oxygen dynamics. The magnitude of these changes is context-specific, depending on the water body, climate, and array configuration.

A life-cycle perspective broadens the focus to include upstream emissions, anchoring-induced sediment disturbance, and end-of-life waste.

Key Gaps: Most Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) neglect ecological endpoints, empirical data is limited, and policy frameworks rarely incorporate ecological risk metrics.

Future Directions: Future work should prioritize long-term, standardized monitoring; interdisciplinary models should be developed that fuse remote sensing with ecosystem dynamics and refine LCAs to incorporate spatial and ecological indicators.

Social Acceptance

Generally speaking, the installation of artificial structures on water bodies, e.g., FPVs, raises concerns that extend beyond technical and environmental factors to include social acceptance.

Despite being viewed as a way to alleviate land competition, FPVs received only 65.3% approval among survey participants who were already supportive of Renewable Energy Sources (RESs) [

55]. The study reveals an inverse relationship between FPV acceptance and its perceived alteration of landscape beauty. Concerns about the impact on fish and birds were also common.

Ways to Increase Acceptance: Diminishing the visibility of FPV installations, along with making FPVs accessible and reducing energy costs for activities in the water basin areas, were suggested ways to improve public opinion.

Social Cost of Energy (SCOE)

A comprehensive methodology for calculating the Social Cost of Energy (SCOE) for FPV systems has been proposed in Ref. [

56] and applied to a Spanish FPV project.

This methodology uses a multidisciplinary approach, integrating:

- (1)

Life Cycle Assessment to quantify environmental impacts;

- (2)

Economic models to estimate costs and benefits over the system’s lifespan;

- (3)

Social impact analysis to assess the effects on communities and stakeholders.

The SCOE metric offers a valuable tool, but its utility is enhanced when complemented by qualitative assessments and stakeholder engagement to address the inherent subjectivity in weighting socio-economic factors.

7. Conclusions

The use of an ASV in FPV systems offers advantages, but it also presents several technical, operational, and safety challenges that must be carefully addressed to ensure effective and reliable utilization.

In some cases, the limited space and constrained geometries of FPV layouts generate narrow passages. The risk of collision with structures is high, especially in the case of adverse weather conditions in confined spaces. The ASV proposed can exhibit excellent maneuverability, e.g., through differential thrust and lateral movements (especially if a four-thruster configuration is adopted).

Moreover, accidental collisions with panels or floating structures may cause physical damage or lead to electrical failures. Nevertheless, suspended or submerged elements such as cables, anchors, harnesses, or structural supports can trap the vehicle, obstructing its movements. Environmental conditions, such as wind, waves, algae, and floating debris, can deviate the vehicle from its planned trajectory and interfere with sensor reliability.

A four-thruster configuration could also help to overcome this issue.

Furthermore, FPV facilities are often located in remote or isolated areas where radio signal coverage is limited or affected by electromagnetic interference from the infrastructure itself. As a result, communication links may be compromised. A loss of connection with the GCS poses a significant safety risk, thus requiring robust fail-safe strategies. Additionally, the semi-reflective and modular environment of FPV installations complicates the use of image-based navigation, due to reflections and shadows, while also affecting the reliability of ultrasonic and optical sensors.

These challenges do not preclude the use of ASVs in FPV environments but require the development of robust, redundant systems; comprehensive testing in simulated conditions; and a modular design that allows for adaptation in different facility layouts.

The growing adoption of FPV installations in both artificial and natural reservoirs introduces new complexities in terms of inspection and maintenance. Limited accessibility and variable environmental conditions demand more autonomous, adaptable, and cost-effective monitoring solutions. In this context, ASVs can provide sustainable support for inspection tasks and environmental data collection.

This paper presents the development of an affordable robotic surface vehicle designed to automate the monitoring of FPV systems.

The system described represents an initial step toward that goal, due to a low-cost (also compared to existing commercial prototypes and other alternatives), low-impact, highly modular prototype design, with the aim of exploring the technical and operational feasibility in ASV deployment, as well as in the often-constrained environments of FPV plants.

The prototype was developed using open-source hardware and software components, keeping costs low and maximizing both its easy replicability and its adaptability across different operational contexts.

The use of a four-motor configuration will enable static operation mode, considering that ArduPilot natively supports the attitude mode (hold position on each waypoint).

However, the two-thruster boat has demonstrated a high degree of flexibility and excellent maneuvering capabilities too, even under deliberately challenging conditions.

An obstacle-avoidance module based on camera input and neural networks is currently under development, and preliminary results have demonstrated the ability to discriminate between water and non-water regions through image segmentation.

Despite the encouraging results, several areas for improvement have emerged for future operational deployment:

The motor mounting frame requires structural re-engineering.

Thruster connections should be stabilized with professional-grade connectors.

The internal layout needs more rationalization, particularly the batteries and electronics arrangement, to reduce clutter and to enable accommodation for future instrumentation.

The obstacle avoidance system is still at the prototype stage.

In conclusion, the developed prototype demonstrates a robust and versatile platform, offering notable maneuverability and high potentiality for customization.

Even if it is still in the prototype stage, the ASV already reveals significant promise as a supporting tool for both infrastructural and environmental monitoring in FPV, as well as in other controlled aquatic environments.