Microwave-Assisted Chemical Recycling of a Polyurethane Foam for Pipe Pre-Insulation and Reusability of Recyclates in the Original Foam Formulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Recycling of Reference PUF

2.3. Preparation of PUFs

2.4. Characterization of the PUFs

3. Results and Discussion

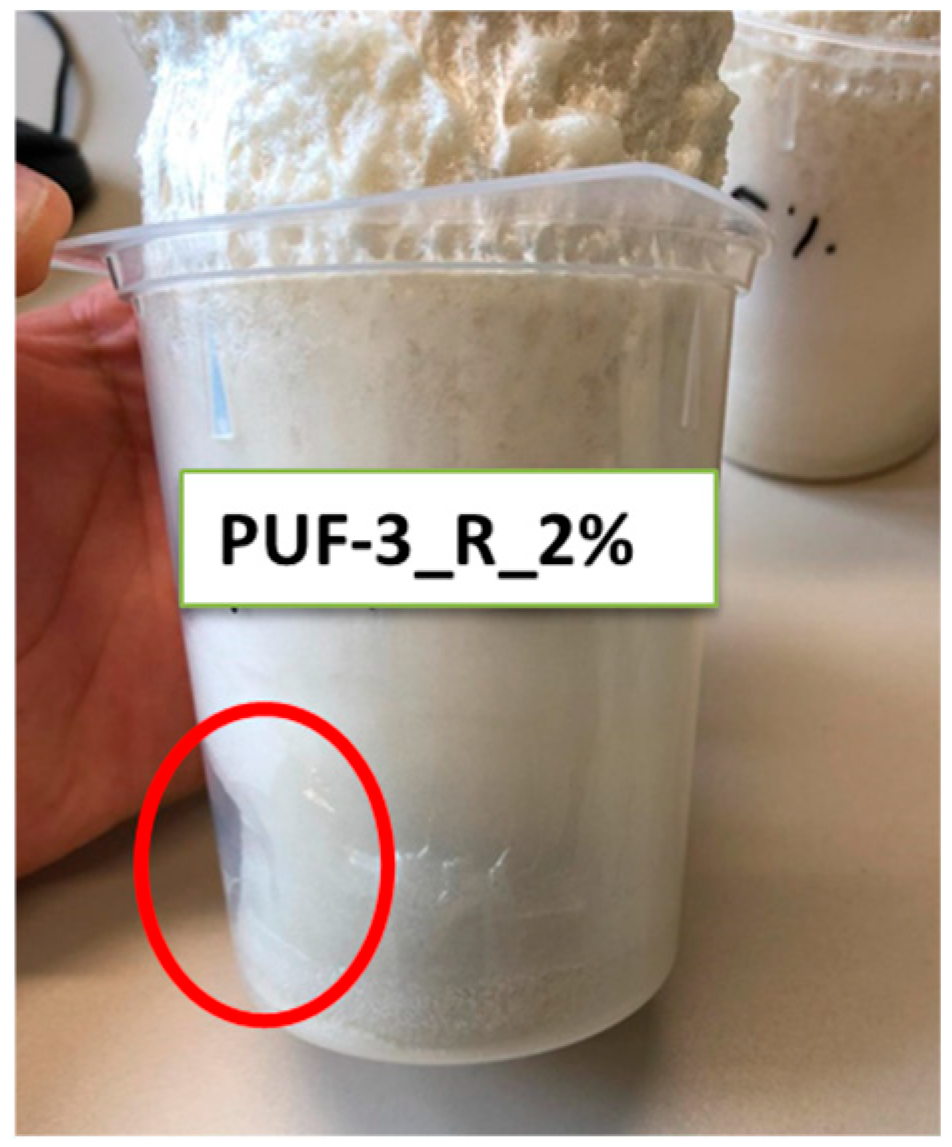

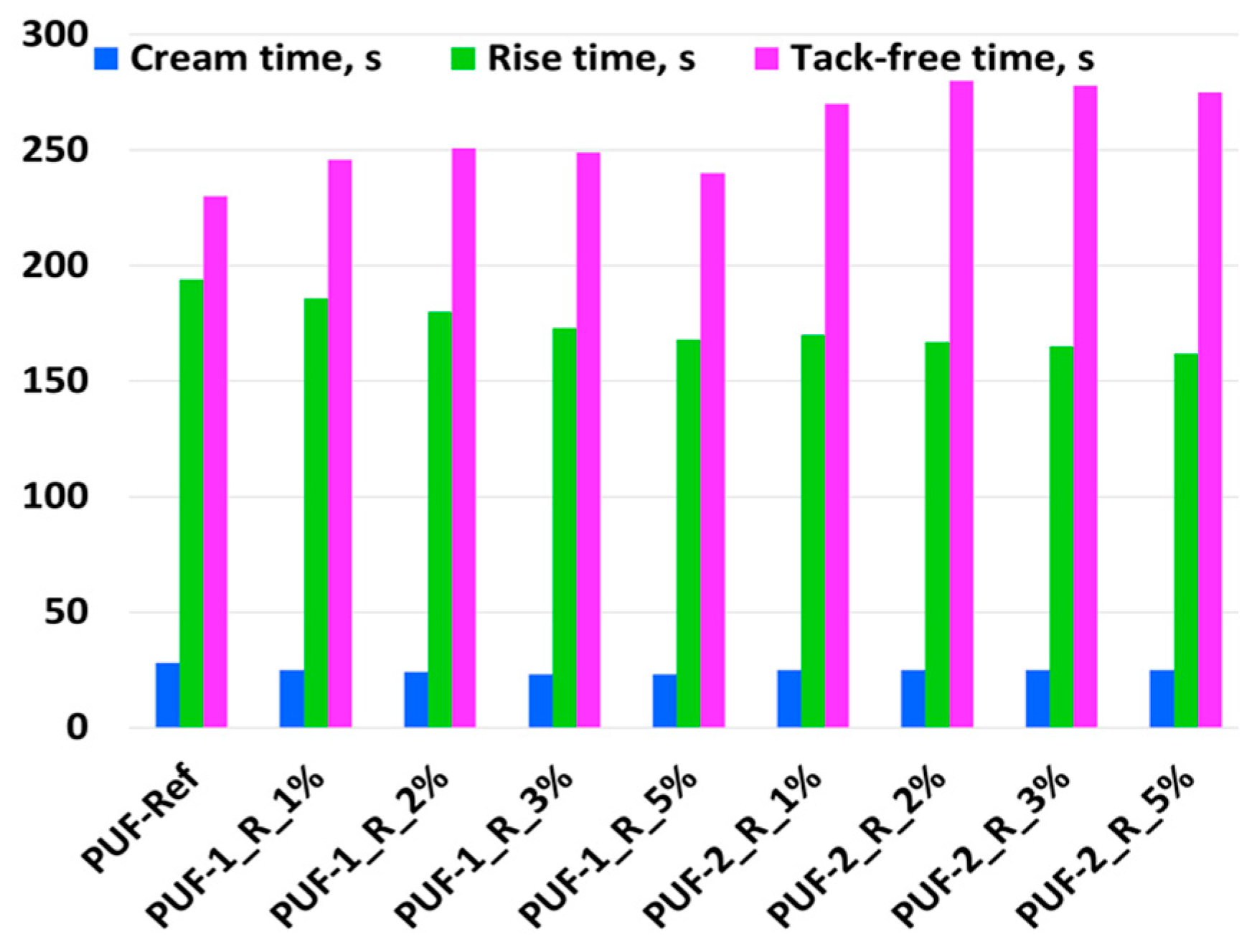

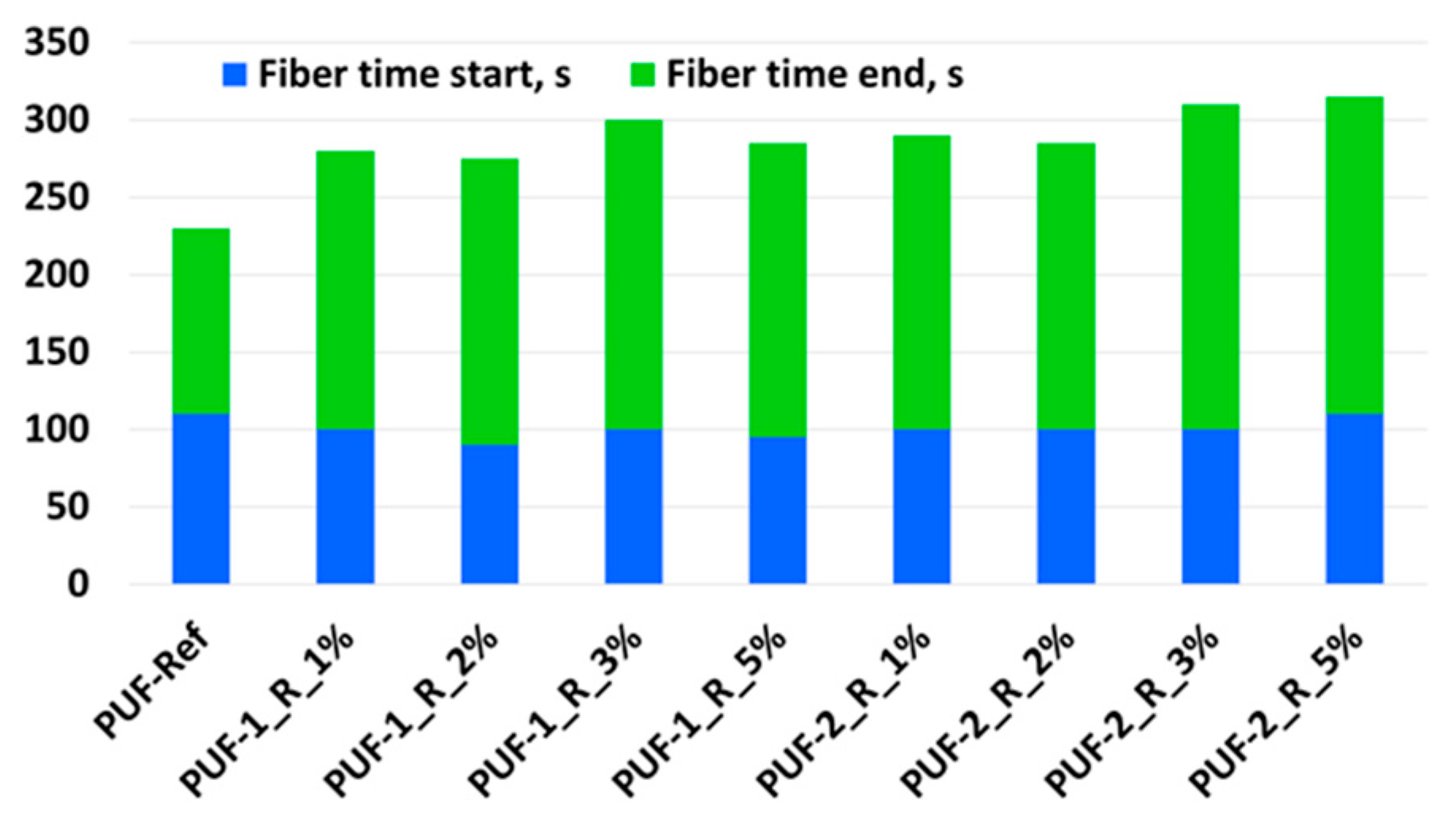

3.1. Influence of Recyclate Type and Amount on the Foaming Parameters

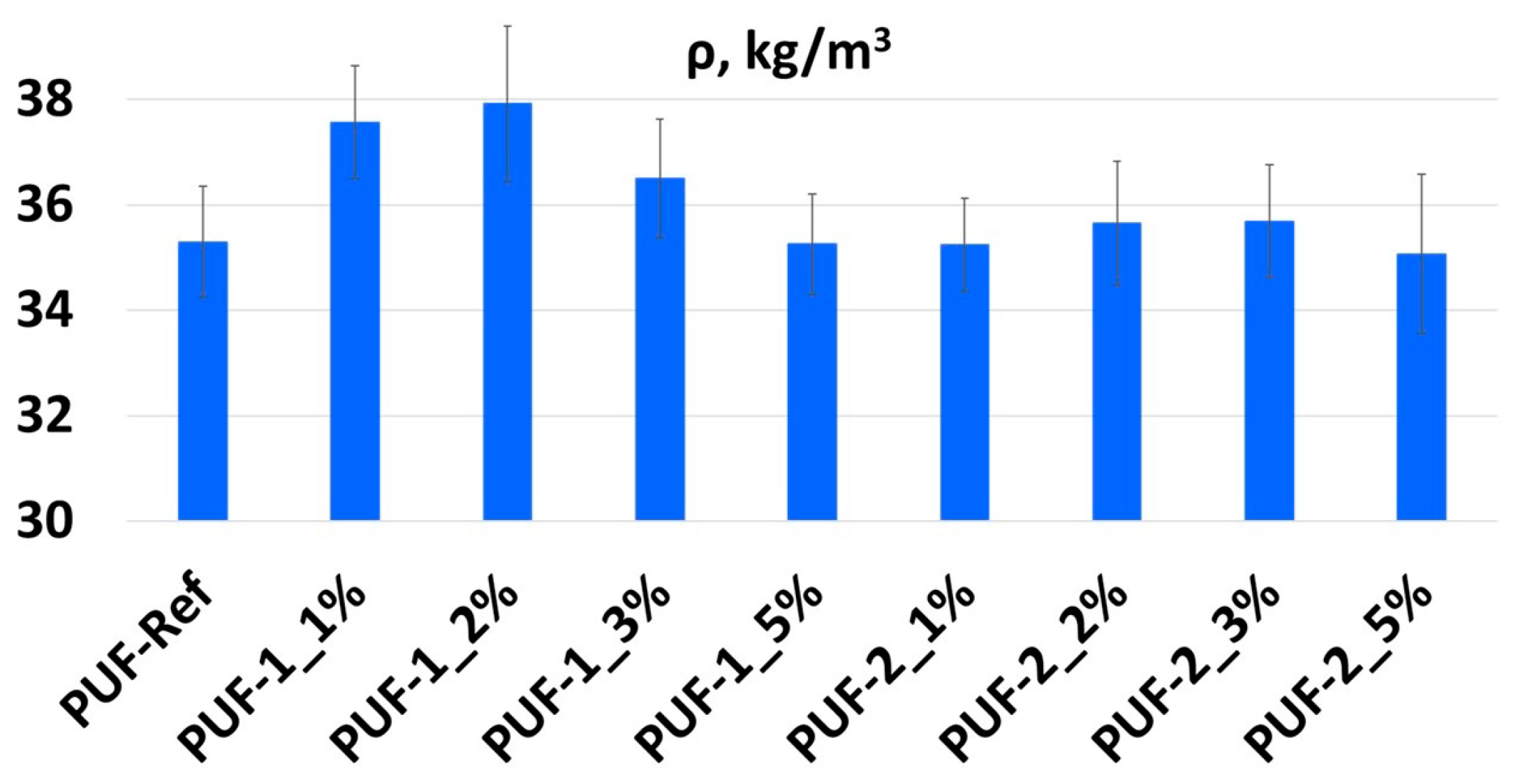

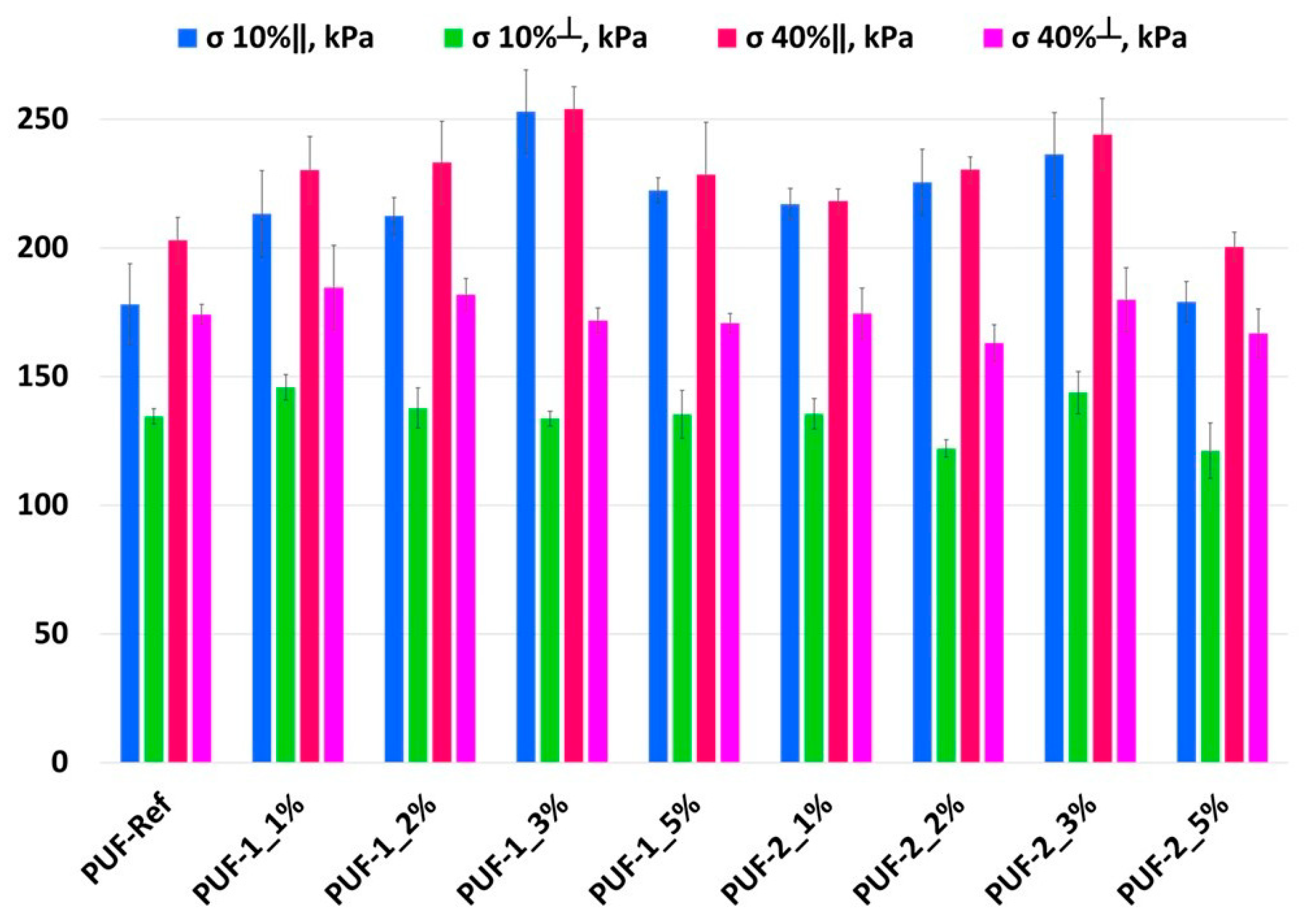

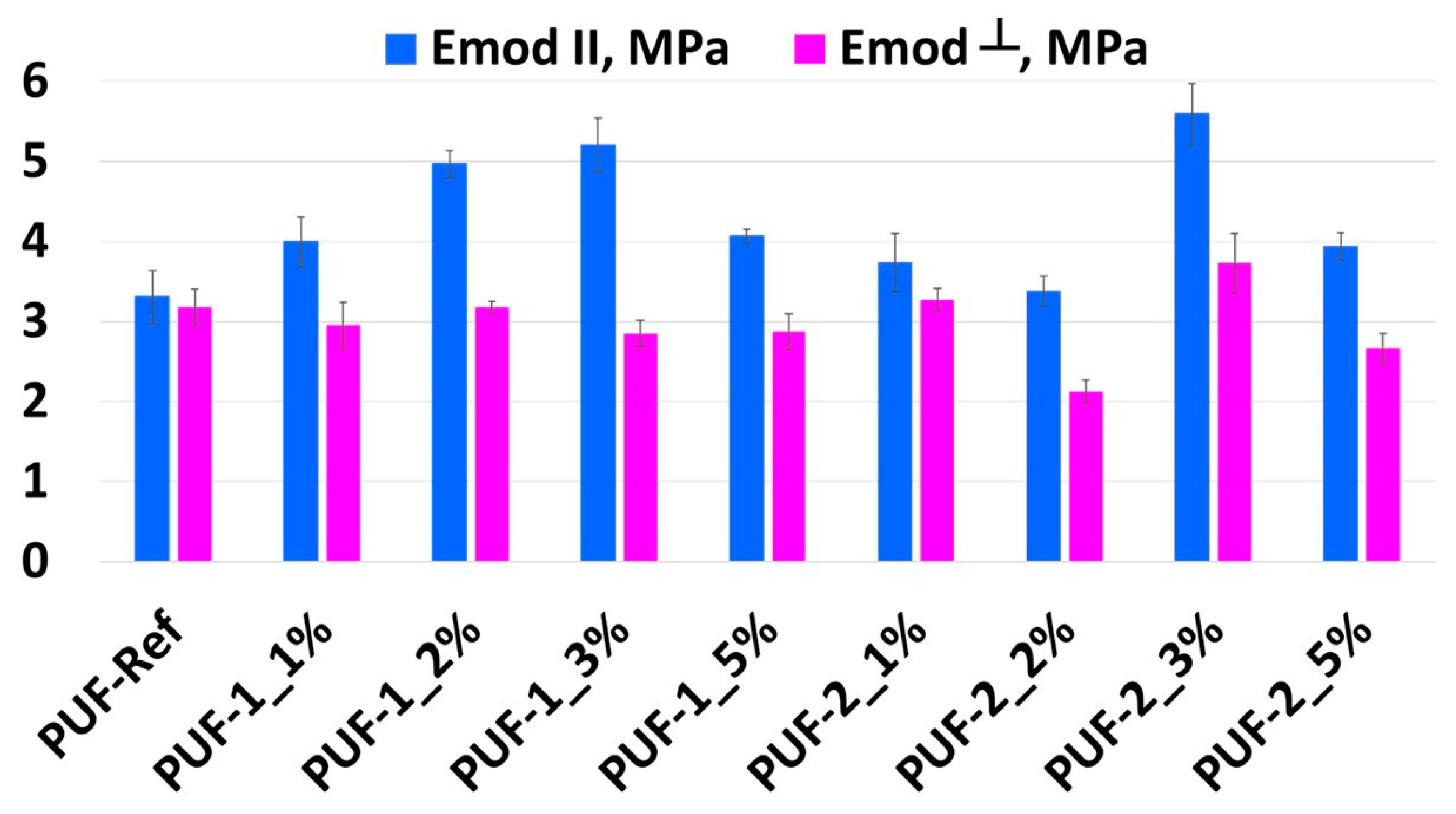

3.2. Influence of Recyclate Type and Amount on the Density and Mechanical Properties of Foams

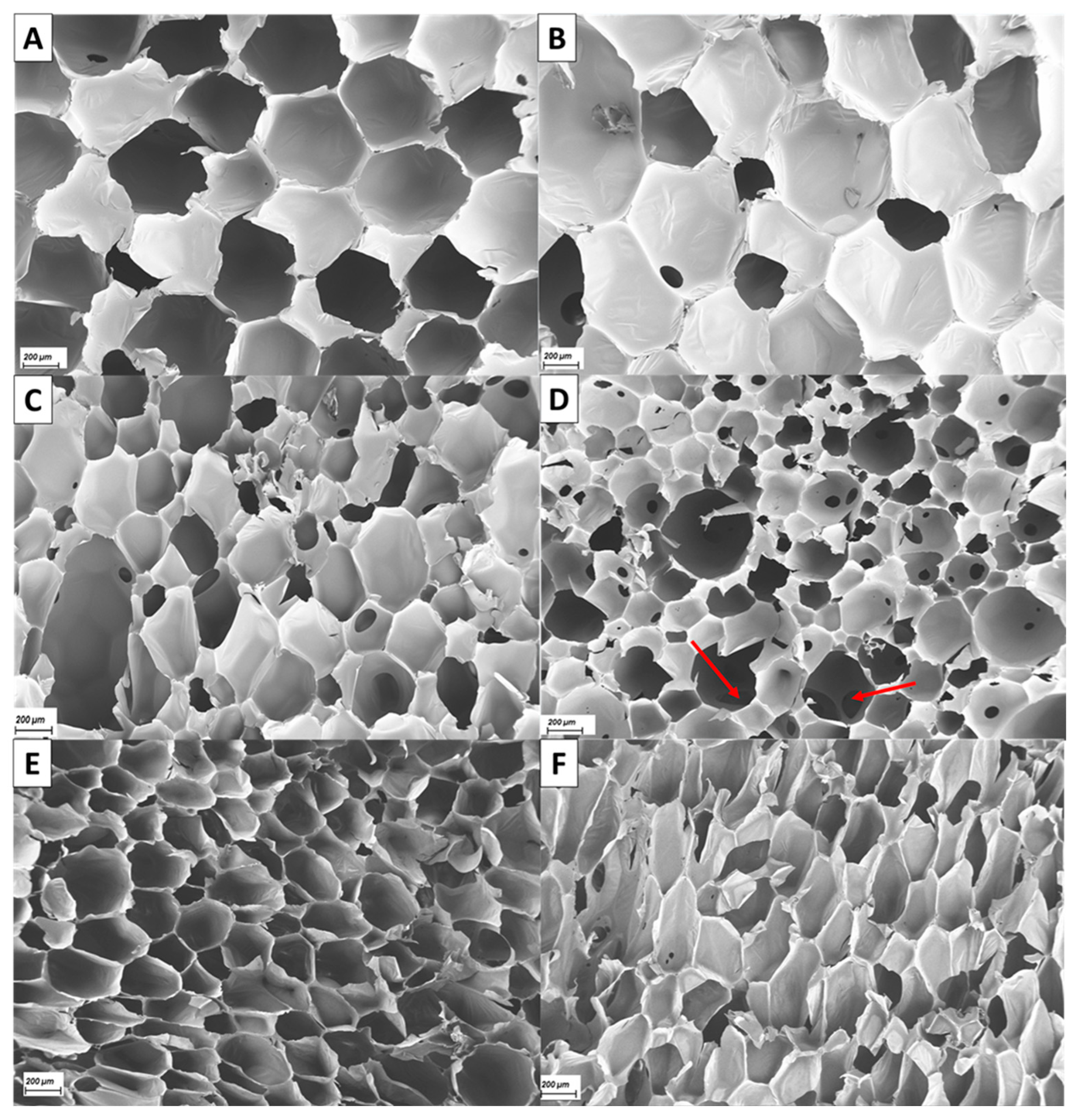

3.3. Morphology of Developed Recyclate-Containing PUFs

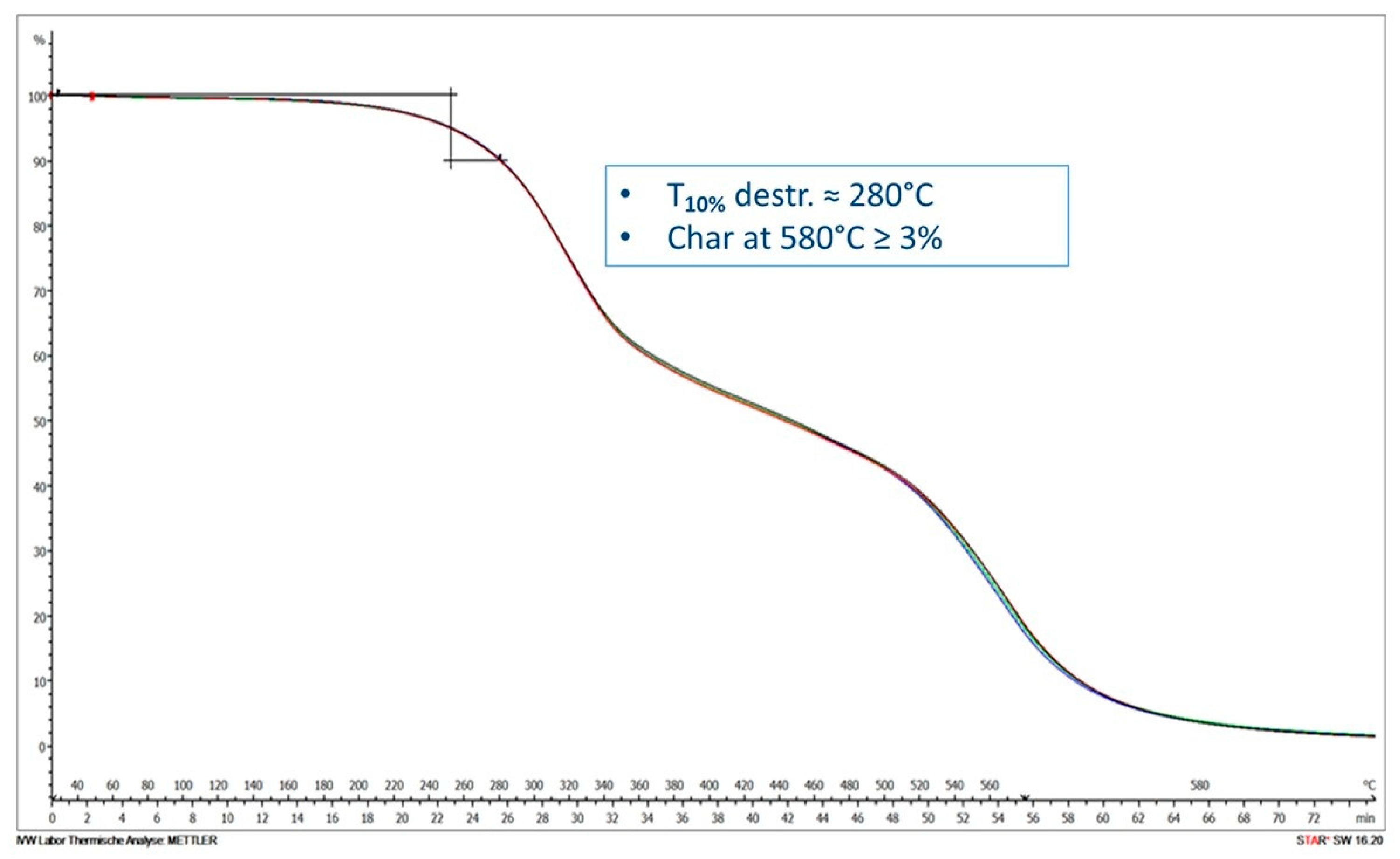

3.4. Thermal Stability of the Developed Recyclate-Containing PUFs

3.5. Moisture Uptake by Developed Recyclate-Containing PUFs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mistry, M.; Prajapati, V.; Dholakiya, B.Z. Redefining Construction: An In-Depth Review of Sustainable Polyurethane Applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 3448–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarathna, H.M.C.C.; Raman, S.N.; Mohotti, D.; Mutalib, A.A.; Badri, K.H. The use of polyurethane for structural and infrastructural engineering applications: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Kingston, T. Silyl-Terminated Polyurethanes for Construction Sealants. J. ASTM Int. 2004, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldzhiev, D.; Mumovic, D.; Strlic, M. Polyurethane insulation and household products—A systematic review of their impact on indoor environmental quality. Build. Environ. 2020, 169, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirpluks, M.; Kalnbunde, D.; Benes, H.; Cabulis, U. Natural oil based highly functional polyols as feedstock for rigid polyurethane foam thermal insulation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 122, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, K.; Ye, L.; He, X. Large-scale model testing of high-pressure grouting reinforcement for bedding slope with rapid-setting polyurethane. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 3083–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, H.-W.; Pirkl, H.-G.; Albers, R.; Albach, R.W.; Krause, J.; Hoffmann, A.; Casselmann, H.; Dormish, J. Polyurethanes: Versatile Materials and Sustainable Problem Solvers for Today’s Challenges. A J. Ger. Chem. Soc. 2013, 52, 9422–9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, F.M.; Choi, J.; Ingsel, T.; Gupta, R.K. High-performance polyurethanes foams for automobile industry. In Micro and Nano Technologies, Nanotechnology in the Automotive Industry; Song, H., Nguyen, T.A., Yasin, G., Singh, N.B., Gupta, R.K., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 105–129. ISBN 9780323905244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, G.D.; Chidambaram, P.K. Evaluation of foam-based composite materials for automotive industry. Mater. Today Proc. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, P.; Loubet, J.-L.; Pavan, S.; Klucker, R. 2K Waterborne Polyurethane Technology for Automotive Clearcoat Applications. Available online: https://www.pcimag.com/articles/92077-2k-waterborne-polyurethane-technology-for-automotive-clearcoat-applications (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Drzeżdżon, J.; Datta, J. Advances in the degradation and recycling of polyurethanes: Biodegradation strategies, MALDI applications, and environmental implications. Waste Manag. 2025, 198, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, A.J.; Tangestani, M.; Zarezadeh, E. Confronting the Environmental Fallout due to Polyurethane Waste and Microplastic Pollution: Mini-review. Shahroud J. Med. Sci. 2025, 11, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhu, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. Analysis of the Influencing Factors of the Efficient Degradation of Waste Polyurethane and Its Scheme Optimization. Polymers 2023, 15, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, D.; Borreguero, A.M.; de Lucas, A.; Rodríguez, J.F. Recycling of polyurethanes from laboratory to industry, a journey towards the sustainability. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, D.; de Lucas, A.; Rodríguez, J.F.; Borreguero, A.M. Glycolysis of high resilience flexible polyurethane foams containing polyurethane dispersion polyol. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 133, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, D.; Borreguero, A.M.; de Lucas, A.; Rodríguez, J.F. Valorization of crude glycerol as a novel transesterification agent in the glycolysis of polyurethane foam waste. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 121, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Kwak, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Ha, J.U.; Oh, J.S. Recycling of bio-polyurethane foam using high power ultrasound. Polymer 2020, 186, 122072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversion of Polyurethane Foam Wastes to Polyols. Available online: https://iceberg-project.eu/conversion-of-polyurethane-foam-wastes-to-polyols/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Sheppard, D.T.; Jin, K.; Hamachi, L.S.; Dean, W.; Fortman, D.J.; Ellison, C.J.; Dichtel, W.R. Reprocessing Postconsumer Polyurethane Foam Using Carbamate Exchange Catalysis and Twin-Screw Extrusion. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignolo, G.; Malucelli, G.; Lorenzetti, A. Recycling of polyurethanes: Where we are and where we are going. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 1132–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemona, A.; Piotrowska, M. Polyurethane Recycling and Disposal: Methods and Prospects. Polymers 2020, 12, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, L.P.; Duval, A.; Luna, E.; Ximenis, M.; De Meester, S.; Avérous, L.; Sardon, H. Reducing the carbon footprint of polyurethanes by chemical and biological depolymerization: Fact or fiction? Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 41, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiounn, T.; Smith, R.C. Advances and approaches for chemical recycling of plastic waste. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Westman, Z.; Richardson, K.; Lim, D.; Stottlemyer, A.L.; Farmer, T.; Gillis, P.; Vlcek, V.; Christopher, P.; Abu-Omar, M.M. Opportunities in Closed-Loop Molecular Recycling of End-of-Life Polyurethane. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 6114–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, H.; Almansour, F.H.; Aldhafeeri, Z. Plastic Waste Management: A Review of Existing Life Cycle Assessment Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyurethane (PU) Recycling: Growing Challenge and Innovation. Available online: https://www.plasticsengineering.org/2024/06/polyurethane-pu-recycling-growing-challenge-and-innovation-005198/#! (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Pau, D.S.W.; Fleischmann, C.M.; Delichatsios, M.A. Thermal decomposition of flexible polyurethane foams in air. Fire Saf. J. 2020, 111, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S. Effect of structure on the thermal stability of crosslinked poly(ester-urethane). Polimery 2009, 54, 120–125. Available online: https://www.ichp.vot.pl/index.php/p/article/view/1183 (accessed on 23 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Coccia, F.; Gryshchuk, L.; Moimare, P.; Bossa, F.d.L.; Santillo, C.; Barak-Kulbak, E.; Verdolotti, L.; Boggioni, L.; Lama, G.C. Chemically Functionalized Cellulose Nanocrystals as Reactive Filler in Bio-Based Polyurethane Foams. Polymers 2021, 13, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieleniewska, M.; Leszczynski, M.K.; Szczepkowski, L.; Bryskiewicz, A.; Bien, K.; Ryszkowska, J. Development and applicational evaluation of the rigid polyurethane foam composites with egg shellwaste. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 132, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component, g | PUF-1_R | PUF-2_R | PUF-3_R |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foam | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Phytic acid, 50% | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Urea | 0.05 | ------------ | ------------ |

| Glycerol | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| PEG 300 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 2-Aminoethan-1-ol | ------------ | 0.5 | ------------ |

| Components | Master Foam, Amounts in g | Recyclate-Containing Foams, Amount in g |

|---|---|---|

| Component A | 100 | 100-X |

| Recyclate | -/- | X |

| Cyclopentane | 12 | 12 |

| Component B | 160 | 160 |

| Sample | Moisture Uptake, % | Sample | Moisture Uptake, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| PUF-Ref | 4.04 ± 0.44 | ||

| PUF-1_R_1% | 3.68 ± 0.23 | PUF-2_R_1% | 3.76 ± 0.42 |

| PUF-1_R_2% | 3.54 ± 0.19 | PUF-2_R_2% | 3.59 ± 0.61 |

| PUF-1_R_3% | 3.28 ± 0.58 | PUF-2_R_3% | 3.33 ± 0.30 |

| PUF-1_R_5% | 2.99 ± 0.34 | PUF-2_R_5% | 3.16 ± 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gryshchuk, L.; Grishchuk, S.; Grun, G.; Almustafa, W. Microwave-Assisted Chemical Recycling of a Polyurethane Foam for Pipe Pre-Insulation and Reusability of Recyclates in the Original Foam Formulation. AppliedChem 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010002

Gryshchuk L, Grishchuk S, Grun G, Almustafa W. Microwave-Assisted Chemical Recycling of a Polyurethane Foam for Pipe Pre-Insulation and Reusability of Recyclates in the Original Foam Formulation. AppliedChem. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGryshchuk, Liudmyla, Sergiy Grishchuk, Gregor Grun, and Wael Almustafa. 2026. "Microwave-Assisted Chemical Recycling of a Polyurethane Foam for Pipe Pre-Insulation and Reusability of Recyclates in the Original Foam Formulation" AppliedChem 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010002

APA StyleGryshchuk, L., Grishchuk, S., Grun, G., & Almustafa, W. (2026). Microwave-Assisted Chemical Recycling of a Polyurethane Foam for Pipe Pre-Insulation and Reusability of Recyclates in the Original Foam Formulation. AppliedChem, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010002