Hydrothermal Synthesis of FAU-Type Zeolite NaX Using Ladle Slag and Waste Aluminum Cans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Acid Treatment of Ladle Slag

3. Results

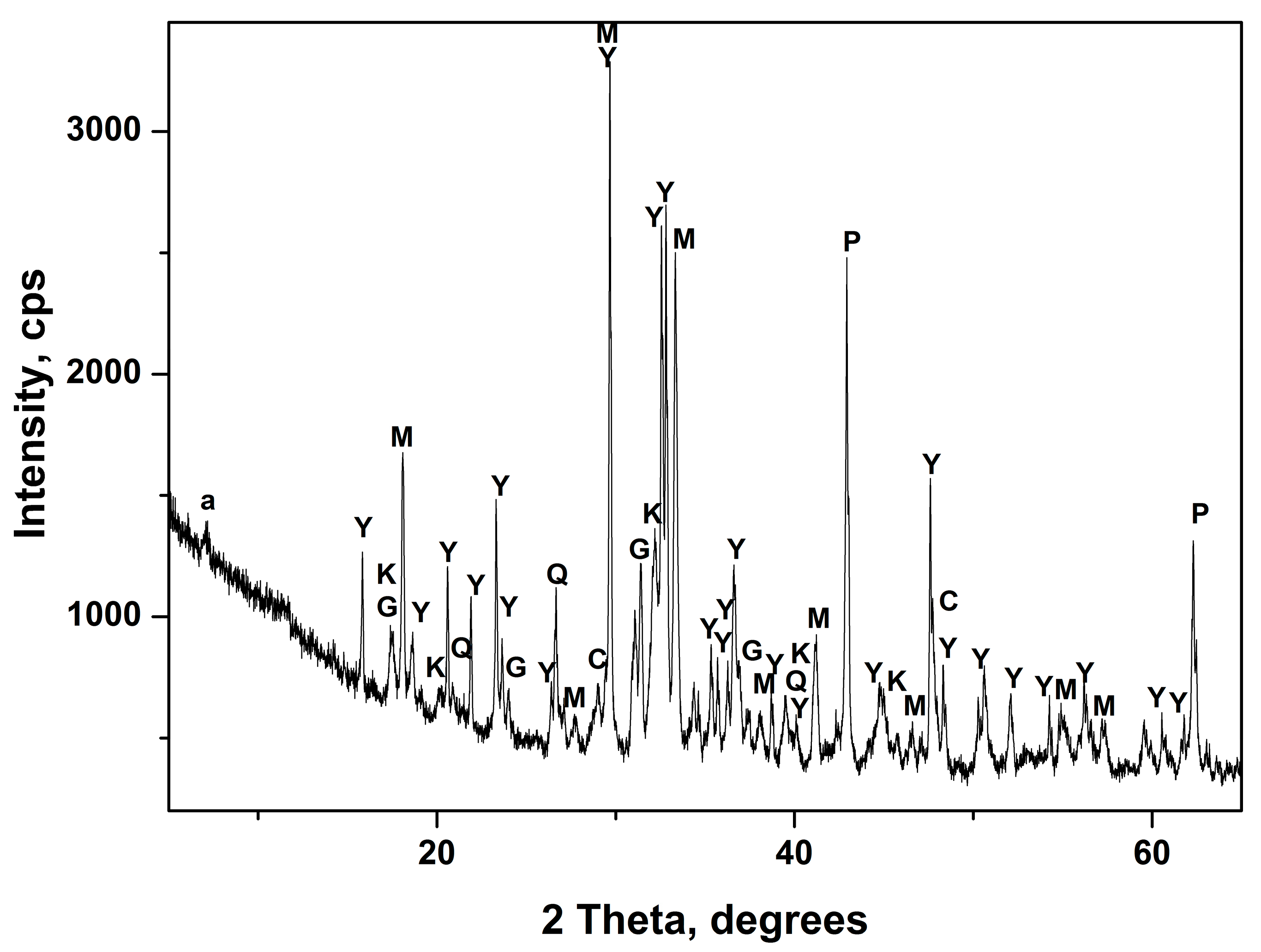

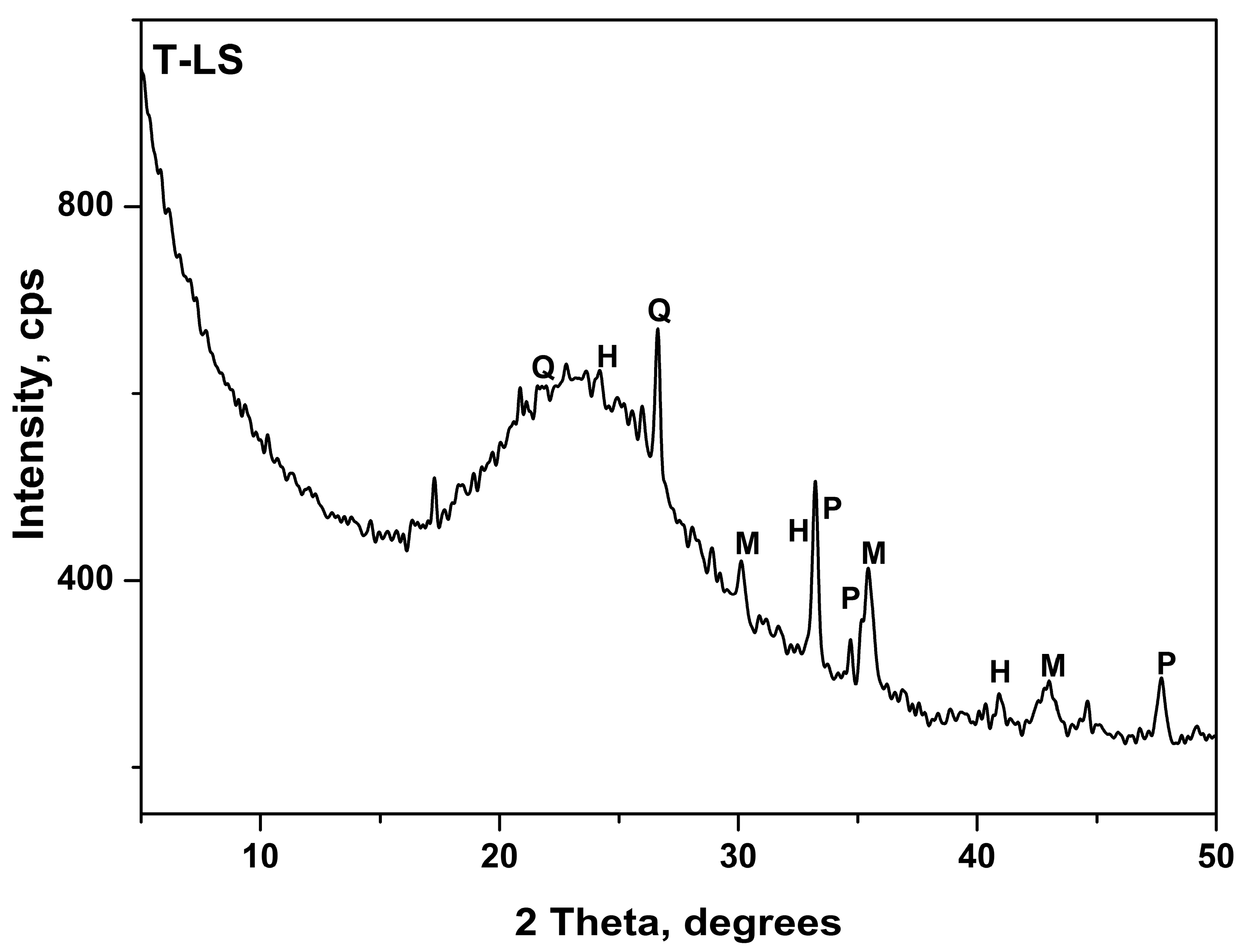

3.1. Acid Treatment of Ladle Slag

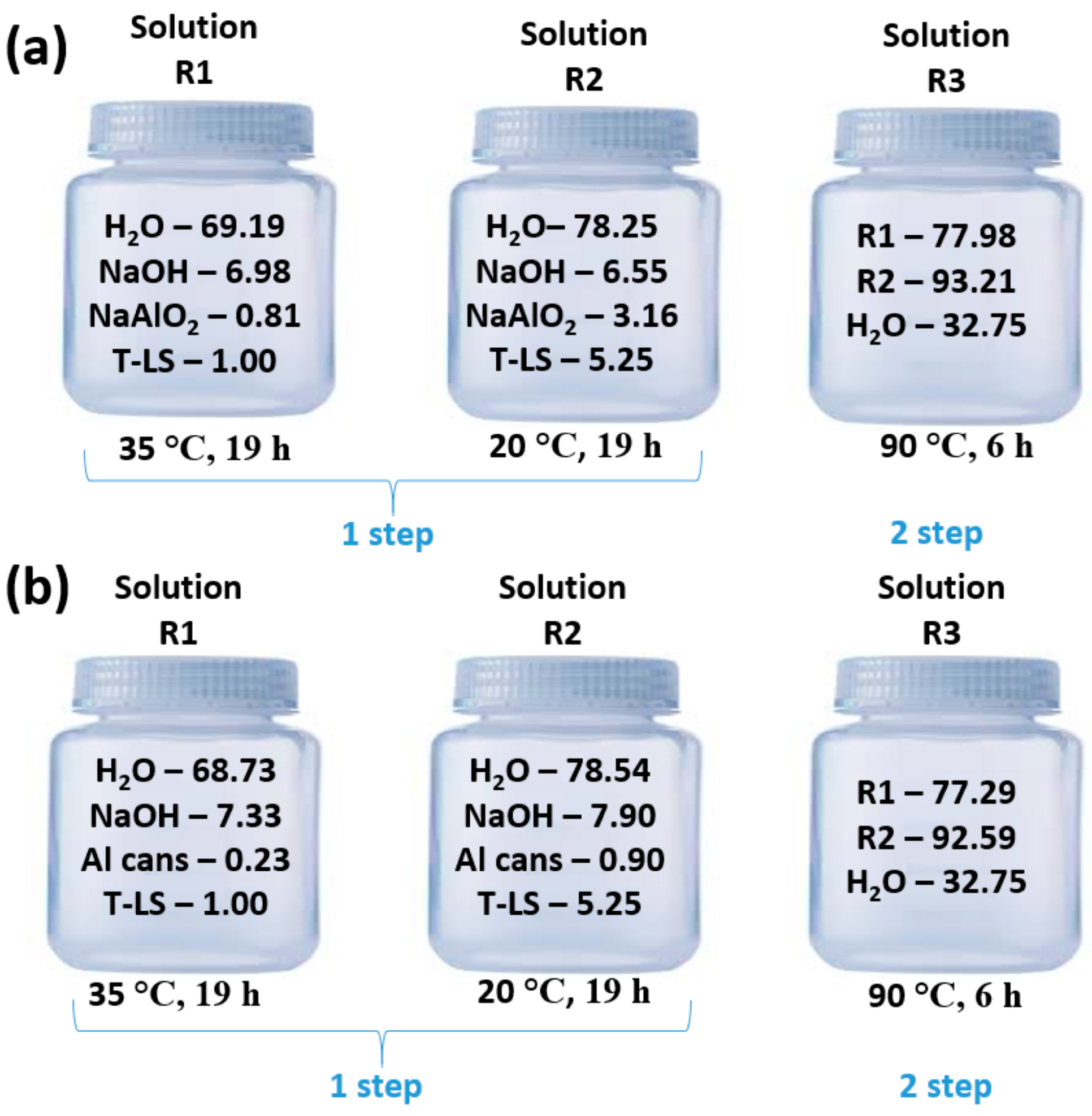

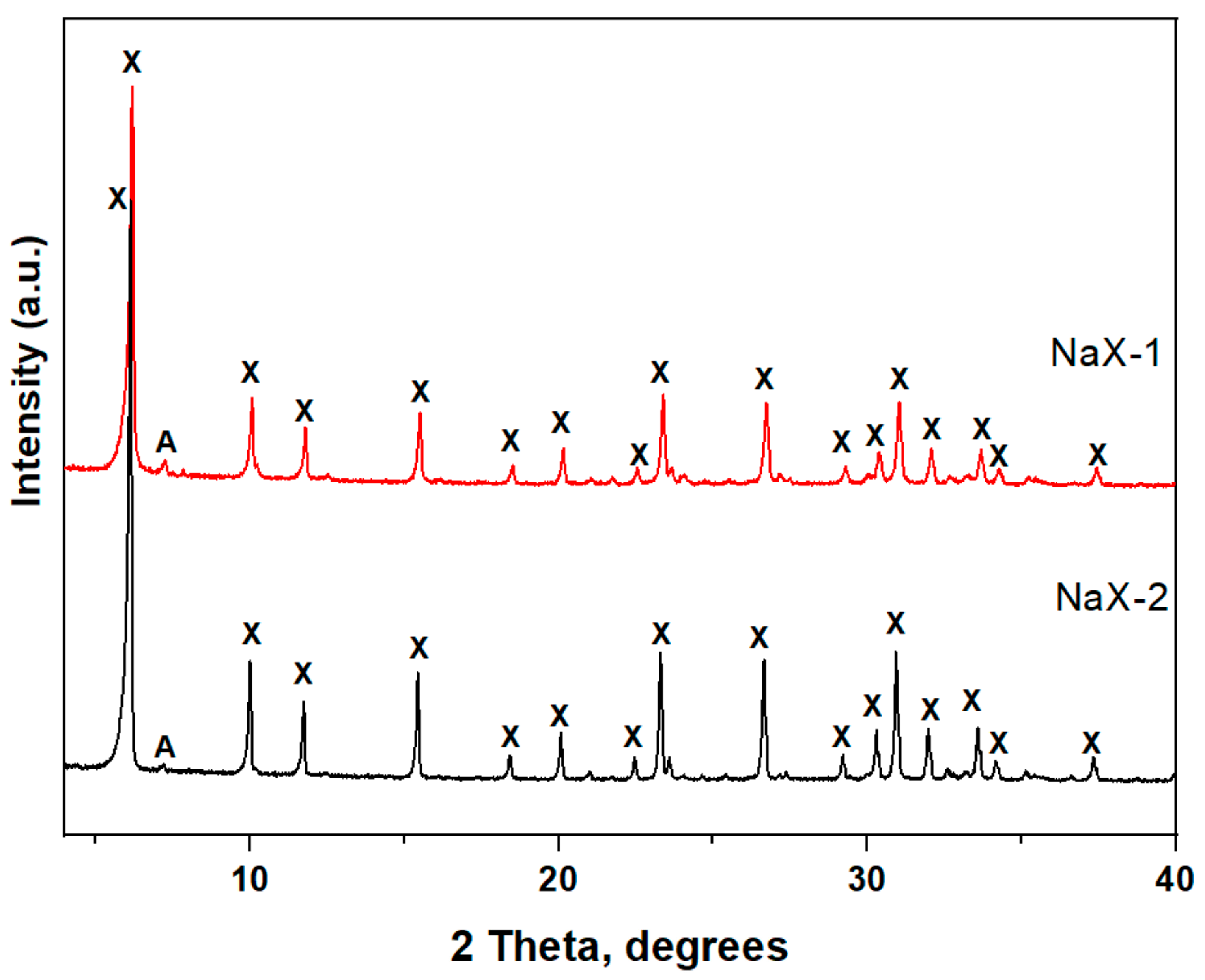

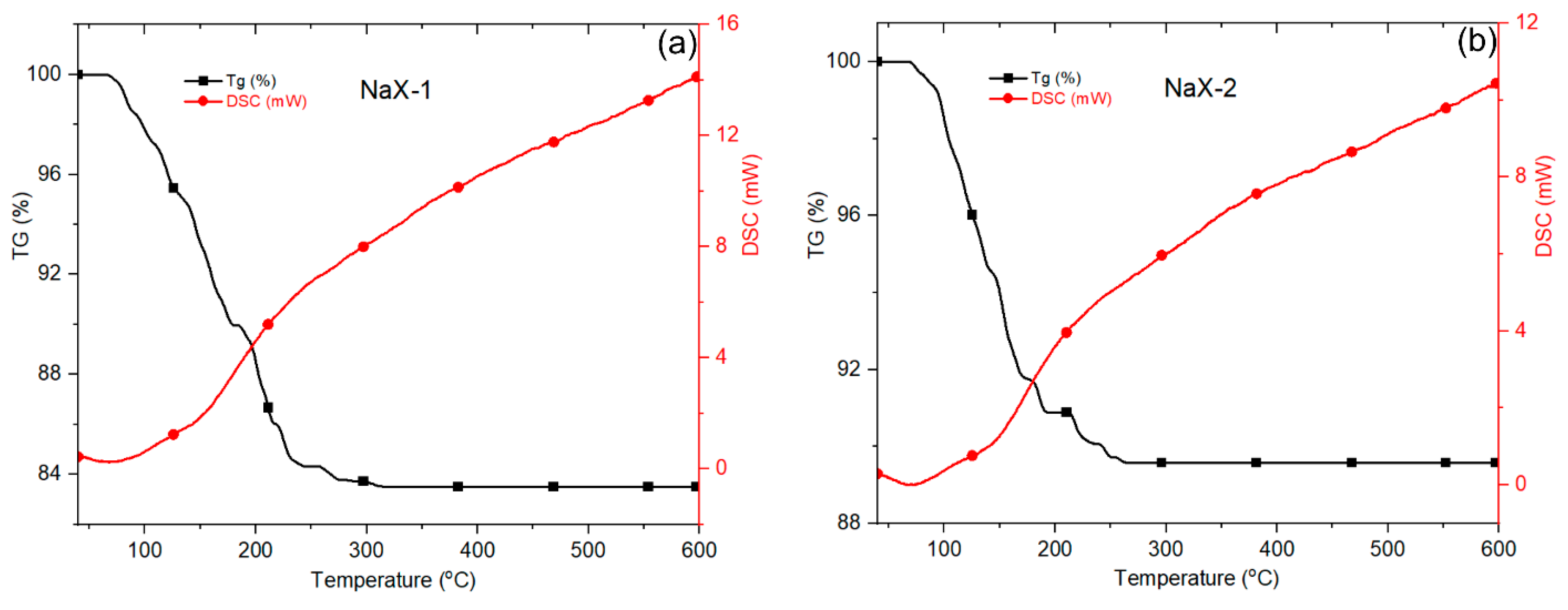

3.2. Synthesis of Zeolite X

3.3. Microstructural Characterization of Zeolite X

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LS | Ladle slag |

| T-LS | Treated Ladle Slag |

References

- Davis, M.E. Ordered porous materials for emerging applications. Nature 2002, 417, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgar Pour, Z.; Abu Zeitoun, E.; Alassmy, Y.A.; El Hariri El Nokab, M.; Van Steenberge, P.H.M.; Sebakhy, K.O. Impact of Synthesis Parameters on the Crystallinity of Macroscopic Zeolite Y Spheres Shaped Using Resin Hard Templates. Crystals 2024, 14, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breck, D.W. Zeolite Molecular Sieves: Structure, Chemistry, and Use; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemian, H.; Gedik, K.; İmamoğlu, İ. Environmental applications of natural zeolites. In Handbook of Natural Zeolites; Bentham Science Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 473–508. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Weitkamp, J. Zeolites and catalysis. Solid State Ion. 2000, 131, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frising, T.; Leflaive, P. Extraframework cation distributions in X and Y faujasite zeolites: A review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, J. Applications of zeolites in sustainable chemistry. Chem 2017, 3, 928–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boycheva, S.; Zgureva, D.; Barbov, B.; Kalvachev, Y. Synthetic micro-and nanocrystalline zeolites for environmental protection systems. In Nanoscience Advances in CBRN Agents Detection, Information and Energy Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Barbov, B.; Zaharieva, K.; Karakashkova, P.; Penchev, H.; Tsvetanova, L.; Dimova, S. Preparation and Catalytic Study of Mn-NaX, Cu-NaX and Ag-/AgNPs-NaX Zeolites. Eng. Proc. 2023, 37, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Gao, M.; Yan, W.; Yu, J. Regulation of the Si/Al ratios and Al distributions of zeolites and their impact on properties. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 1935–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneyer, A.; Ke, Q.; Devos, J.; Dusselier, M. Zeolite synthesis under nonconventional conditions: Reagents, reactors, and modi operandi. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 4884–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoldi, M.; Fuentes-Ordoñez, E.; Korili, S.; Gil, A. Zeolite synthesis from industrial wastes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 287, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallapur, V.P.; Oubagaranadin, J.U.K. A brief review on the synthesis of zeolites from hazardous wastes. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 2017, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Shibata, J. Mechanism of zeolite synthesis from coal fly ash by alkali hydrothermal reaction. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2002, 64, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Plana, F.; Alastuey, A.; López-Soler, A. Synthesis of Na-zeolites from fly ash. Fuel 1997, 76, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, S.; Barbov, B.; Todorova, T.; Kolev, H.; Ivanova, I.; Shopska, M.; Kalvachev, Y. CO oxidation over Pt-modified fly ash zeolite X. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2020, 129, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirova, T.; Kirov, G. Modification of zeolite Na-X, sodalite and cancrinite in salt melts. Geol. Balc. 2023, 52, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Wang, Y.; Ding, D.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Z.; Yan, K.; Gao, J.-M. Zeolite functional materials synthesized from coal gangue. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 20986–21011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Ly, K.-P.; Thanh, L.H.V.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Santoso, S.P.; Tran, N.-P.-D.; Tsai, M.-L.; Ju, Y.-H. Facile synthesis of zeolite NaX using rice husk ash without pretreatment. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 123, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoldi, M.; Fuentes-Ordoñez, E.; Korili, S.; Gil, A. Zeolite synthesis from aluminum saline slag waste. Powder Technol. 2020, 366, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Hu, X.; Shi, L.; Cui, Q.; Wang, H.; Yao, H. Synthesis and characterization of zeolite X from lithium slag. Appl. Clay Sci. 2012, 59, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, T.; Man, W.; Ju, L.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, M.; Guo, M. Hydrothermal synthesis of mixtures of NaA zeolite and sodalite from Ti-bearing electric arc furnace slag. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 8358–8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyembe, N.; Isa, Y.M. Acid leaching of blast furnace slag for enhanced zeolite synthesis. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 10, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, G.; Steenbruggen, G.; Janssen-Jurkovičová, M. A two-step process for the synthesis of zeolites from coal fly ash. Fuel 1999, 78, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, A.; Łach, M.; Mierzwiński, D.; Bajda, T.; Mikuła, J. Obtaining zeolites from slags and ashes from a waste combustion plant in an autoclave process. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: London, UK, 2017; p. 00026. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, A.; Kostov, V.; Petrova, N.; Tsvetanova, L.; Vassilev, S.V.; Titorenkova, R. Sunflower Shells Biomass Fly Ash as Alternative Alkali Activator for One-Part Cement Based on Ladle Slag. Ceramics 2025, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintova, S.; Gilson, J.-P.; Valtchev, V. Advances in nanosized zeolites. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6693–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippens, B.C.; De Boer, J. Studies on pore systems in catalysts: V. T method. J. Catal. 1965, 4, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Terzyk, A.P.; Gauden, P.A.; Solarz, L. Numerical analysis of Horvath–Kawazoe equation. Comput. Chem. 2002, 26, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The determination of pore volume and area distributions in porous substances. I. Computations from nitrogen isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Qian, J. High performance cementing materials from industrial slags—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2000, 29, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.-h.; Zhang, S.-g.; Wang, D.-w.; Fang, K.-m. Hydrothermal preparation and crystal habit of X-zeolite powder. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2005, 12, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhainaut, J.; Daou, T.; Chappaz, A.; Bats, N.; Harbuzaru, B.; Lapisardi, G.; Chaumeil, H.; Defoin, A.; Rouleau, L.; Patarin, J. Synthesis of FAU and EMT-type zeolites using structure-directing agents specifically designed by molecular modelling. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 174, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintova, S. Verified Syntheses of Zeolitic Materials; Synthesis Commission of the International Zeolite Association: Caen, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mintova, S.; Olson, N.H.; Valtchev, V.; Bein, T. Mechanism of zeolite A nanocrystal growth from colloids at room temperature. Science 1999, 283, 958–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, M.; Sahadeo, E.; Libera, R.; Maurizi, A.; Giles, I.; Marteel-Parrish, A. An undergraduate research experience: Synthesis, modification, and comparison of hydrophobicity of zeolites A and X. Polyhedron 2016, 114, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundy, C.S.; Cox, P.A. The hydrothermal synthesis of zeolites: Precursors, intermediates and reaction mechanism. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 82, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Lv, Y.; Jing, T.; Gao, X.; Gu, Z.; Li, S.; Ao, H.; Fang, D. Recent progress on the synthesis and applications of zeolites from industrial solid wastes. Catalysts 2024, 14, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.; Cabrera, S.; Hedlund, J.; Mouzon, J. Selective synthesis of FAU-type zeolites. J. Cryst. Growth 2018, 489, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiprich, B.; Weissenberger, T.; Schwieger, W.; Inayat, A. Layer-like FAU-type zeolites: A comparative view on different preparation routes. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moogooee, M.T. Chloride Binding and Desorption Mechanism in Blended Cement Containing Supplementary Cementitious Materials Exposed to De-icing Brine Solutions. Doctoral Dissertation, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzler, C.; Alves, N.; Pereira, E.; Nienczewski, J.; Ligabue, R.; Einloft, S.; Dullius, J. CO2 storage with indirect carbonation using industrial waste. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgbemere, H.; Ekpe, I.; Lawal, G. Zeolite synthesis, characterization and application areas: A review. Int. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 6, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeddine, Z.; Batonneau-Gener, I.; Pouilloux, Y.; Hamad, H.; Saad, Z. Synthetic nax zeolite as a very efficient heavy metals sorbent in batch and dynamic conditions. Colloids Interfaces 2018, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, E.L.; Nenova, E.P.; Yocheva, L.D.; Ivanova, I.A.; Georgiev, P.A. Antimicrobial and oxidative activities of different levels of silver-exchanged zeolites X and ZSM-5 and their ecotoxicity. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krachuamram, S.; Chanapattharapol, K.C.; Kamonsutthipaijit, N. Synthesis and characterization of NaX-type zeolites prepared by different silica and alumina sources and their CO2 adsorption properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 310, 110632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundy, C.S.; Cox, P.A. The Hydrothermal Synthesis of Zeolites: History and Development from the Earliest Days to the Present Time. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 663–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Leaf-nosed bat. In Encyclopædia Britannica; Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Querol, X.; Moreno, N.; Umaña, J.t.; Alastuey, A.; Hernández, E.; Lopez-Soler, A.; Plana, F. Synthesis of zeolites from coal fly ash: An overview. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2002, 50, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrer, R. Occurrence, classification and some properties of zeolites. In Hydrothermal Chemistry of Zeolites; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, K.; Chao, C.Y.H.; Kot, S. Removal of mixed heavy metal ions in wastewater by zeolite 4A and residual products from recycled coal fly ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 127, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.; Chao, C.Y.H. Effects of step-change of synthesis temperature on synthesis of zeolite 4A from coal fly ash. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 88, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovo, A.S.; Hernandez, O.; Holmes, S. Synthesis and characterization of zeolite Y and ZSM-5 from Nigerian Ahoko Kaolin using a novel, lower temperature, metakaolinization technique. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 6207–6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Getman, R.B. The significant differences in solvation thermodynamics of C1–C3 oxygenates in hydrophilic versus hydrophobic pores of a hydrophilic Ti-FAU zeolite model. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 19367–19379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Peng, S.; Liu, W.; Mei, D. Understanding the hydrocracking of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons within FAU zeolites: Hydrogen splitting catalyzed by the frustrated Lewis pair. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 8083–8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejka, J.; Corma, A.; Zones, S. Zeolites and Catalysis: Synthesis, Reactions and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | K2O | SO3 | TiO2 | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS | 12.20 | 13.75 | 2.77 | 61.01 | 5.56 | 0.09 | 3.12 | 0.87 | 0.63 |

| T-LS | 83.00 | 3.78 | 2.41 | 1.54 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 3.41 | 3.43 | 1.47 |

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Na2O | CaO | MgO | K2O | SO3 | TiO2 | Fe2O3 | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaX-1 | 44.3 | 31.4 | 15.6 | 1.18 | 2.49 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 2.56 | 1.83 | 0.46 |

| NaX-2 | 43.9 | 32.5 | 16.9 | 1.14 | 0.554 | 0.095 | 0.076 | 2.44 | 1.83 | 0.565 |

| Sample | SiO2/Al2O3 (mol) | Na2O/Al2O3 (mol) |

|---|---|---|

| NaX-1 (Al cans) | 2.39 | 0.82 |

| NaX-2 (NaAlO2) | 2.29 | 0.86 |

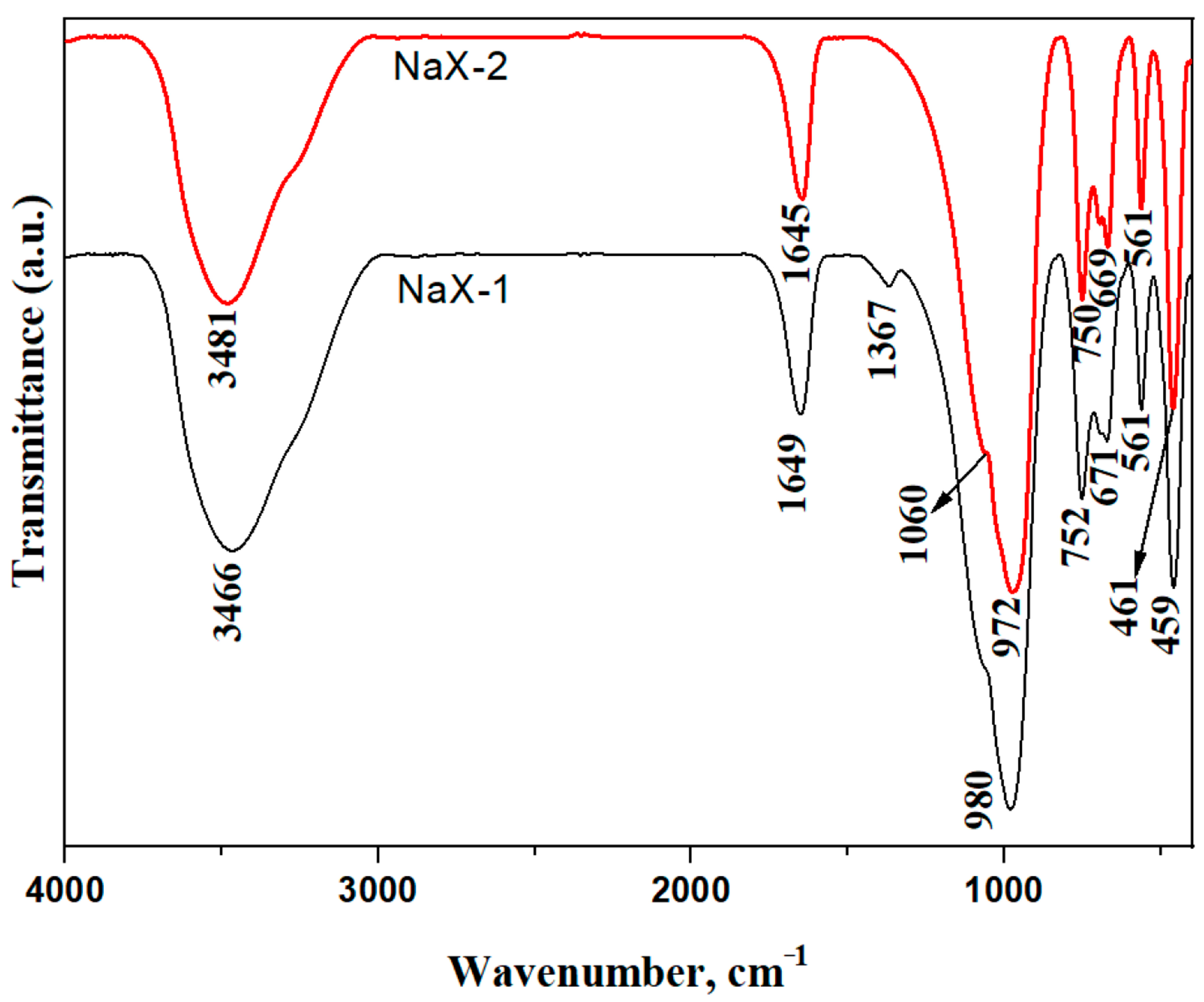

| Wave Number (cm −1) | Vibration Type/ Assignment | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 3481/3466 | O–H stretching vibrations (adsorbed H2O) | Broad band associated with hydrogen-bonded water molecules in zeolitic pores |

| 1645/1649 | H–O–H bending vibrations (adsorbed H2O) | Confirms the presence of water molecules within the zeolite channels |

| 980/972 | Asymmetric T–O–T stretching vibrations (T = Si, Al) | Framework vibrations characteristic of FAU-type aluminosilicates |

| 752/750 | Symmetric T–O stretching vibrations | Vibrations associated with tetrahedral units of the aluminosilicate framework |

| 671/669 | Distorted T–O–T vibrations | Indicative of framework deformation and tetrahedral linkage distortion |

| 561 | Double six-membered ring (D6R) vibrations | Diagnostic band of FAU-type zeolite, confirming NaX framework formation |

| 461/459 | T–O bending vibrations | Low-frequency bending modes of the aluminosilicate framework |

| 3481/3466 | O–H stretching vibrations (adsorbed H2O) | Broad band associated with hydrogen-bonded water molecules in zeolitic pores |

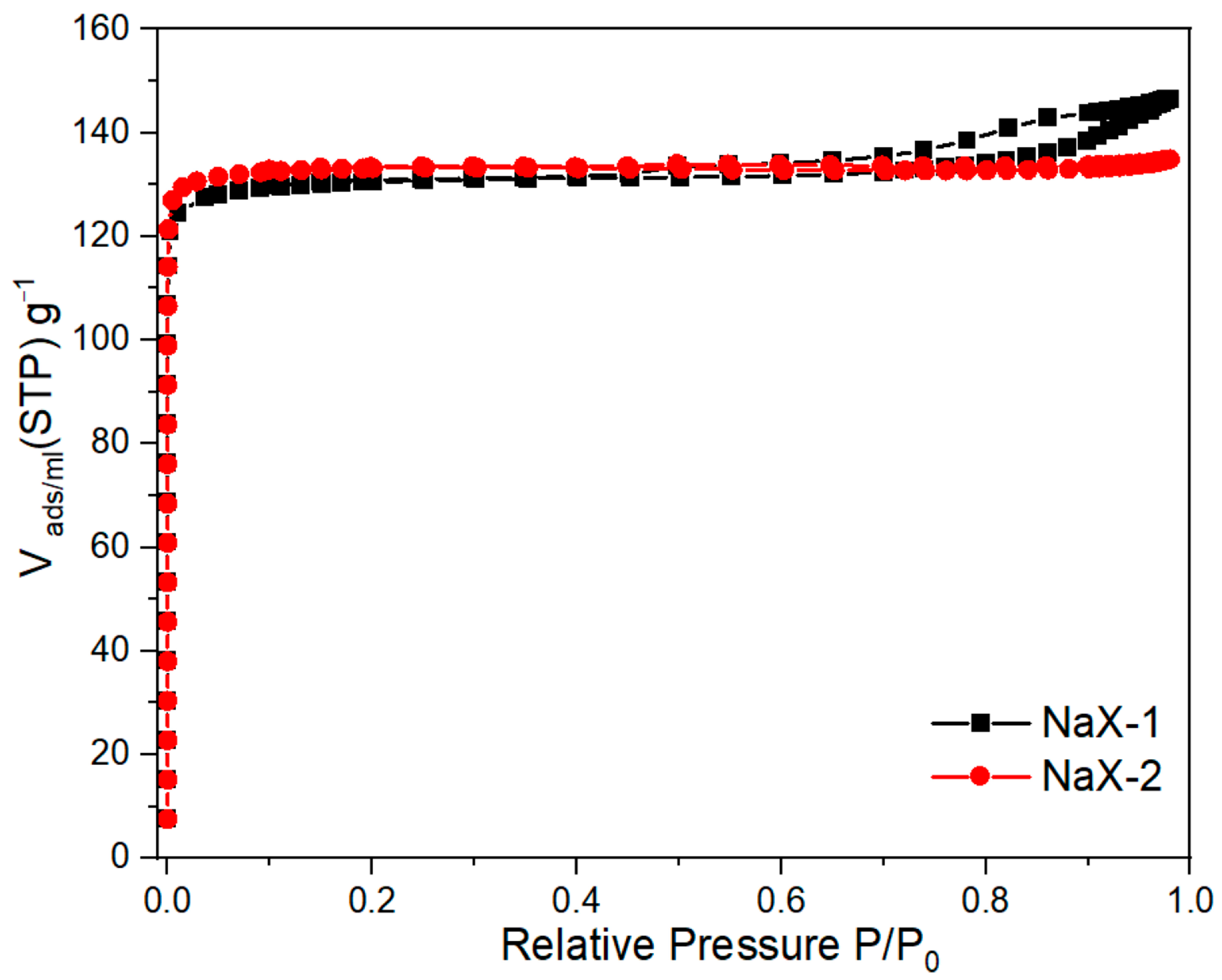

| Samples | SBET m2·g−1 | Vt cm3·g−1 | Average Pore Diameter nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaX-1 | 410.99 | 0.22 | 2.1 |

| NaX-2 | 417.87 | 0.21 | 1.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barbov, B.; Lazarova, H.; Tsvetanova, L.; Nikolov, A. Hydrothermal Synthesis of FAU-Type Zeolite NaX Using Ladle Slag and Waste Aluminum Cans. AppliedChem 2026, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010012

Barbov B, Lazarova H, Tsvetanova L, Nikolov A. Hydrothermal Synthesis of FAU-Type Zeolite NaX Using Ladle Slag and Waste Aluminum Cans. AppliedChem. 2026; 6(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbov, Borislav, Hristina Lazarova, Liliya Tsvetanova, and Aleksandar Nikolov. 2026. "Hydrothermal Synthesis of FAU-Type Zeolite NaX Using Ladle Slag and Waste Aluminum Cans" AppliedChem 6, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010012

APA StyleBarbov, B., Lazarova, H., Tsvetanova, L., & Nikolov, A. (2026). Hydrothermal Synthesis of FAU-Type Zeolite NaX Using Ladle Slag and Waste Aluminum Cans. AppliedChem, 6(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010012