Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.A.M., F.F.N.A., G.G.I., and N.R.; methodology, M.A.A.A.M., F.F.N.A., G.G.I., and N.Y.; software, M.A.A.A.M. and G.G.I.; validation, M.A.A.A.M., Y.S., and N.Y.; formal analysis, M.A.A.A.M., G.G.I., and Y.S.; investigation, M.A.A.A.M., G.G.I., and N.R.; resources, G.G.I., N.R., and N.Y.; data curation, M.A.A.A.M., G.G.I., and N.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.A.A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.A.A.M. and N.Y.; visualization, M.A.A.A.M.; supervision, Y.S. and N.Y.; project administration, M.A.A.A.M.; funding acquisition, M.A.A.A.M. and N.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

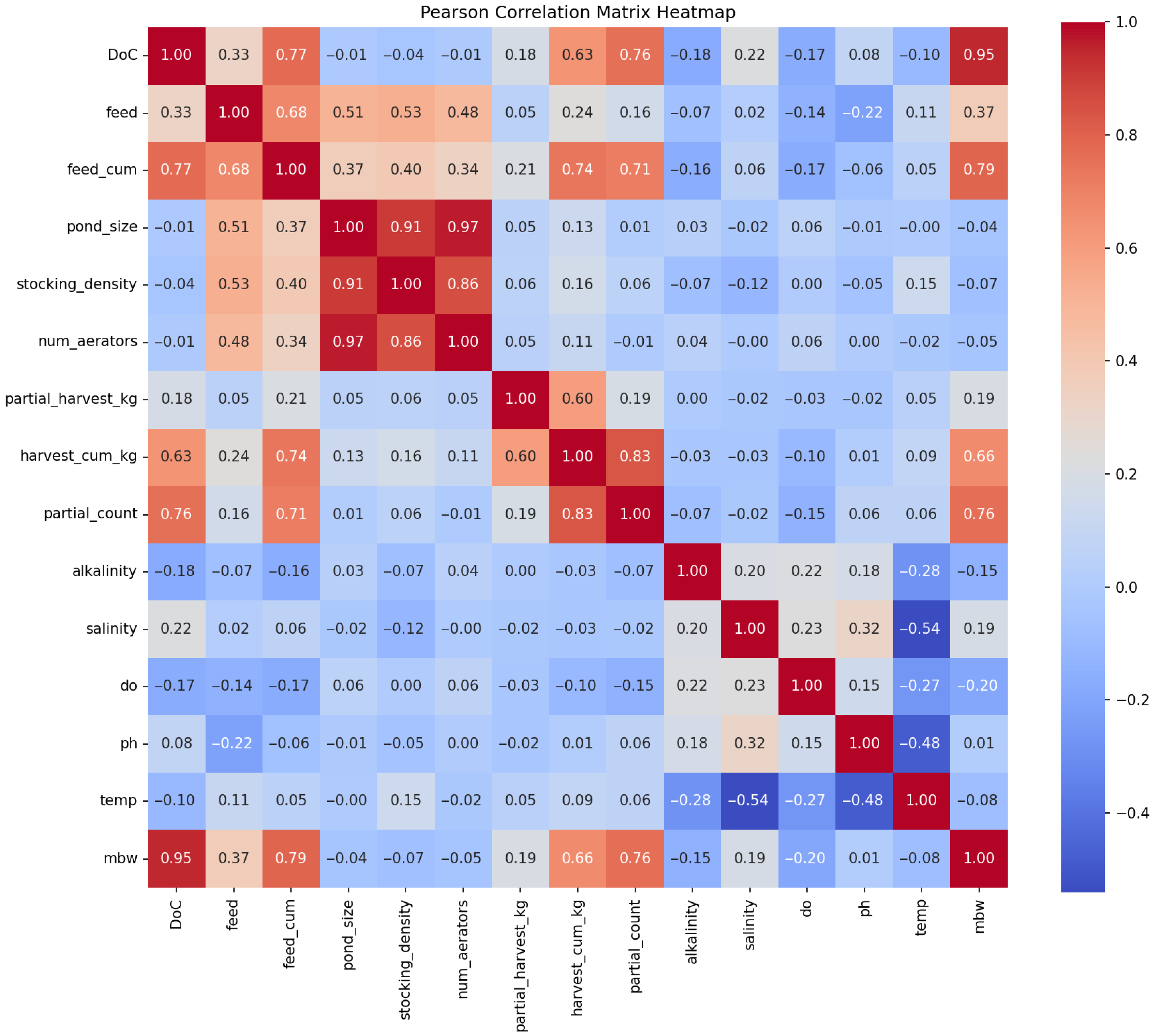

Correlation matrix heatmap showing all pairwise correlations between 14 features and mean body weight (mbw). Red indicates positive correlations, blue indicates negative correlations, and white indicates zero correlation. Features include DoC, feed, feed_cum, pond_size, stocking_density, num_aerators, partial_harvest_kg, harvest_cum_kg, partial_count, alkalinity, salinity, do, and ph. Harvesting-related variables (partial_harvest_kg, harvest_cum_kg, partial_count) show moderate to strong positive correlations with mbw (r = 0.19–0.76), while environmental variables show weak negative correlations (r = −0.08 to −0.20). DoC shows the strongest correlation with mbw (r = 0.95).

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix heatmap showing all pairwise correlations between 14 features and mean body weight (mbw). Red indicates positive correlations, blue indicates negative correlations, and white indicates zero correlation. Features include DoC, feed, feed_cum, pond_size, stocking_density, num_aerators, partial_harvest_kg, harvest_cum_kg, partial_count, alkalinity, salinity, do, and ph. Harvesting-related variables (partial_harvest_kg, harvest_cum_kg, partial_count) show moderate to strong positive correlations with mbw (r = 0.19–0.76), while environmental variables show weak negative correlations (r = −0.08 to −0.20). DoC shows the strongest correlation with mbw (r = 0.95).

Figure 2.

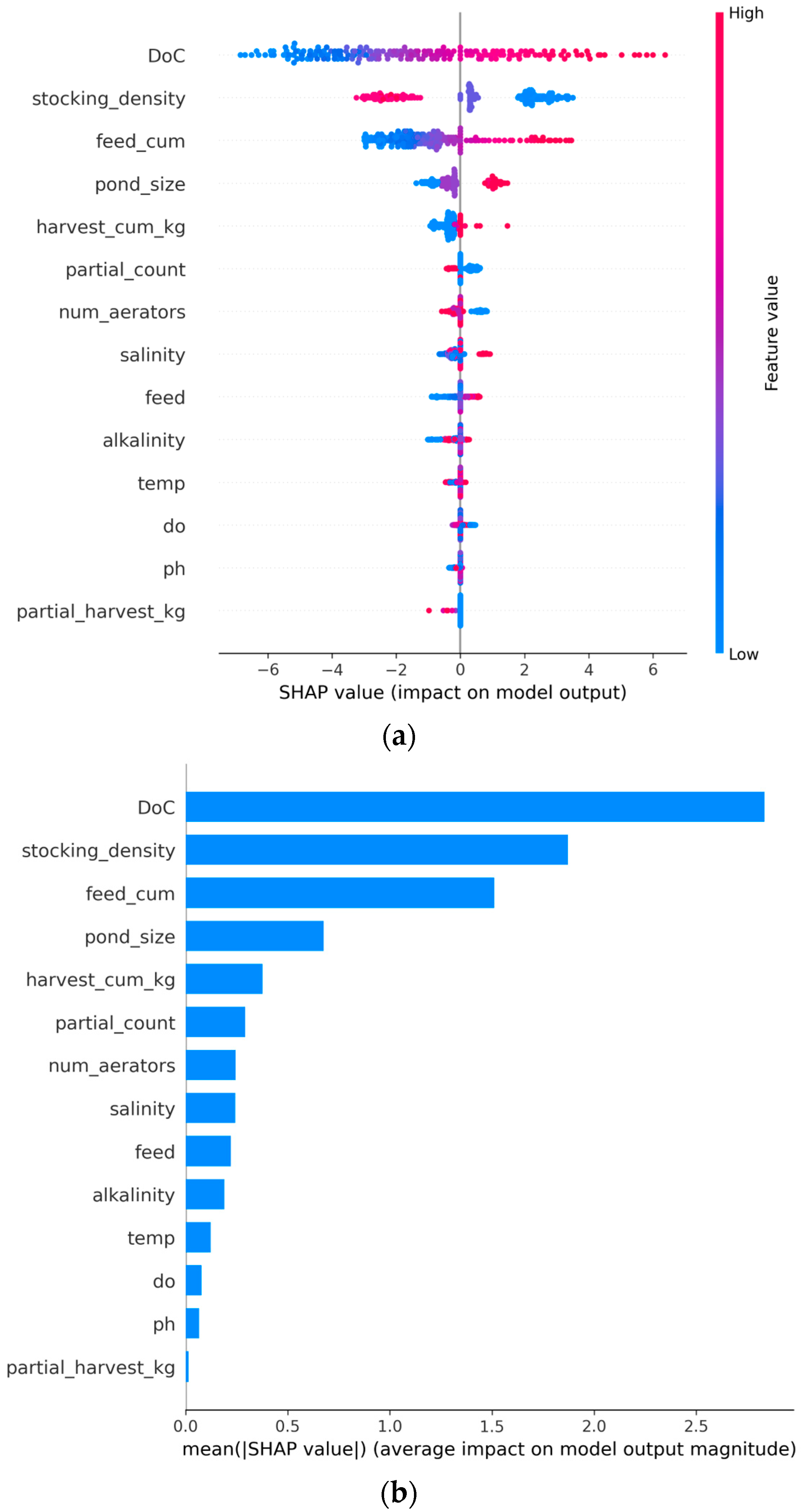

SHAP summary plots showing feature importance rankings. (a) A beeswarm plot displays individual sample SHAP values for each feature, ranked by mean absolute SHAP. Horizontal spread represents the range of SHAP values across samples; DoC shows the widest spread. Color gradient indicates feature values (blue = low values, red = high values). (b) A bar chart displays mean |SHAP| values, ranked from highest to lowest importance. DoC (2.833), stocking_density (1.871), and feed_cum (1.510) rank highest. Harvesting variables harvest_cum_kg and partial_count rank 5th and 6th, respectively; partial_harvest_kg ranks 14th.

Figure 2.

SHAP summary plots showing feature importance rankings. (a) A beeswarm plot displays individual sample SHAP values for each feature, ranked by mean absolute SHAP. Horizontal spread represents the range of SHAP values across samples; DoC shows the widest spread. Color gradient indicates feature values (blue = low values, red = high values). (b) A bar chart displays mean |SHAP| values, ranked from highest to lowest importance. DoC (2.833), stocking_density (1.871), and feed_cum (1.510) rank highest. Harvesting variables harvest_cum_kg and partial_count rank 5th and 6th, respectively; partial_harvest_kg ranks 14th.

Figure 3.

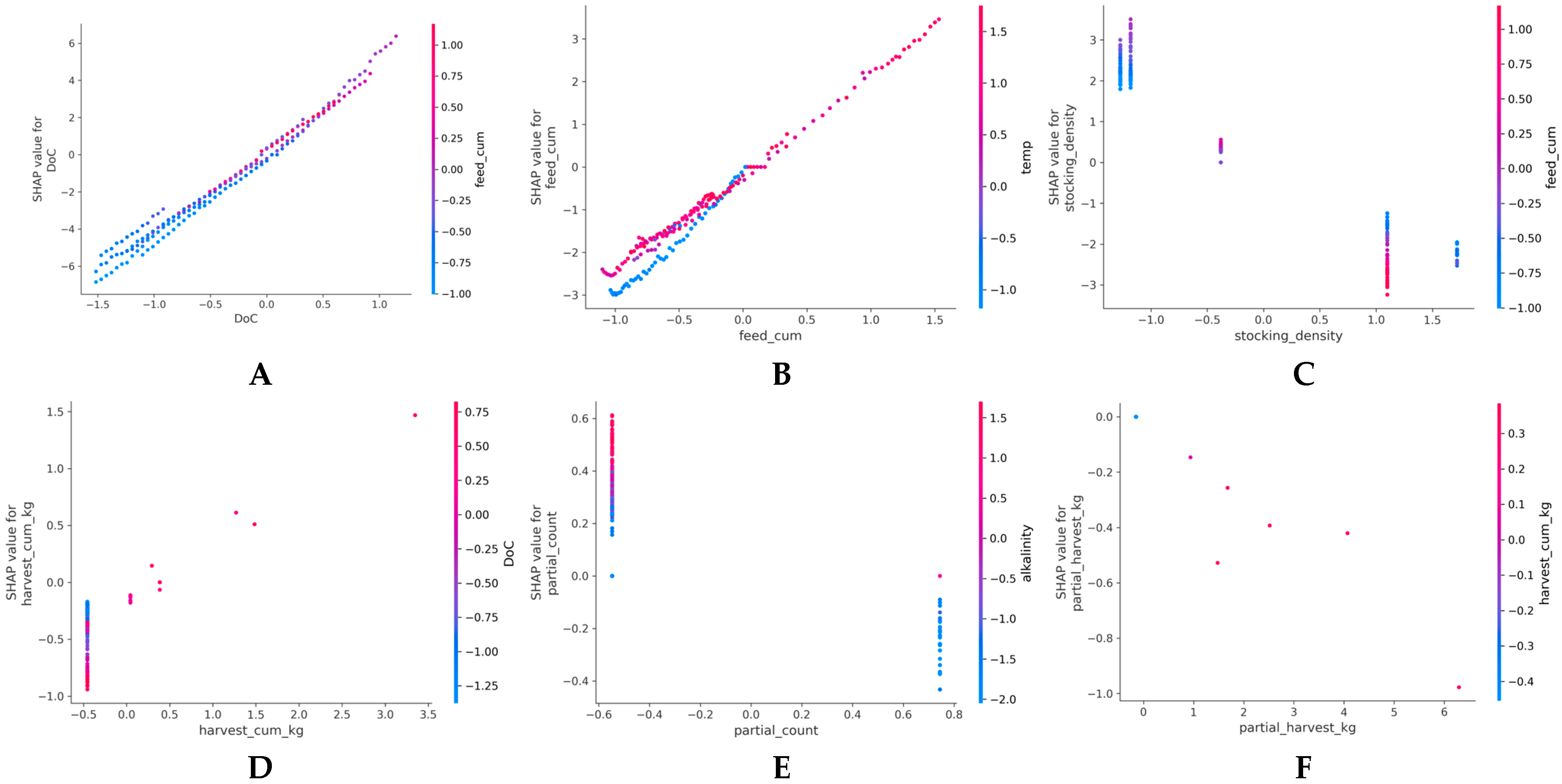

SHAP dependence plots for six key features showing normalized feature values (X-axis) versus SHAP values (Y-axis). (A) DoC demonstrates a linear positive relationship with SHAP values ranging from −6 to +7. (B) Feed_cum demonstrates a positive relationship with SHAP range ±3 and temperature interaction. (C) Stocking_density shows a negative relationship with SHAP values ranging from −3.5 to +3.0. (D) Harvest_cum_kg shows a positive nonlinear trend, with a SHAP range of ±1.5. (E) Partial_count shows a weak positive trend, with SHAP values ranging from ±0.6 and distinct clustering. (F) Partial_harvest_kg demonstrates sparse distribution with minimal SHAP variation (±1.0). Y-axis ranges differ by feature; larger ranges correspond to higher importance.

Figure 3.

SHAP dependence plots for six key features showing normalized feature values (X-axis) versus SHAP values (Y-axis). (A) DoC demonstrates a linear positive relationship with SHAP values ranging from −6 to +7. (B) Feed_cum demonstrates a positive relationship with SHAP range ±3 and temperature interaction. (C) Stocking_density shows a negative relationship with SHAP values ranging from −3.5 to +3.0. (D) Harvest_cum_kg shows a positive nonlinear trend, with a SHAP range of ±1.5. (E) Partial_count shows a weak positive trend, with SHAP values ranging from ±0.6 and distinct clustering. (F) Partial_harvest_kg demonstrates sparse distribution with minimal SHAP variation (±1.0). Y-axis ranges differ by feature; larger ranges correspond to higher importance.

Table 1.

Shrimp farming parameters found in the dataset. This study utilized real production data from a super-intensive outdoor shrimp aquaculture. The data is divided into several categories: temporal, infrastructure, operational, and environmental.

Table 1.

Shrimp farming parameters found in the dataset. This study utilized real production data from a super-intensive outdoor shrimp aquaculture. The data is divided into several categories: temporal, infrastructure, operational, and environmental.

| Category | Parameter | Description |

|---|

| Target | Mean body weight | Mean body weight of shrimp |

| Temporal | Day of cultivation | Rearing period since the introduction of post-larvae to the ponds |

Pond

(Infrastructure) | Stocking density | Initial number of shrimps in a pond |

| Pond size | Pond area in meter square |

| Aerator count | Number of active aerators in a pond |

Feeding

(Operational) | Feeding amount | Total feeding amount in a day |

| Feeding cumulative | Cumulative calculation of feeding amount |

Harvest

(Operational) | Partial harvest cumulative | Cumulative calculation of partial harvest |

| Partial harvest frequency | Frequency of partial harvest |

Water

(Environmental) | pH | pH measurement |

| Temperature | Temperature measurement |

| Salinity | Salinity measurement |

| Dissolved oxygen | Dissolved oxygen measurement |

| Alkalinity | Alkalinity measurement |

Table 2.

Hyperparameter list.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter list.

| Algorithm | Hyperparameters | Grid |

|---|

| Random Forest | Number of trees | 50, 100, 150, 200, 250 |

| Max depth | 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 |

| Min. samples per leaf | 1, 2, 4 |

| Min. samples per split | 2, 5, 10 |

| Feature sampling | ‘sqrt’, ‘log2’ |

| Support Vector Machine | Kernel | ‘linear’, ‘rbf’, ‘poly’ |

| C (Regularization) | 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000 |

| Gamma (for rbf/poly) | ‘scale’, ‘auto’, 0.001, 0.01 |

| Degree (for poly) | 2, 3, 4 |

| Artificial Neural Network | Hidden dimension | 32, 48, 64, 96, 128 |

| Number of hidden layers | 1, 2, 3 |

| Batch size | 8, 16, 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.0001, 0.0005, 0.001, 0.005 |

| Epochs (max) | 80, 100, 150 |

| Early stopping patience | 8, 10, 12 |

| Dropout | 0.0, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 |

| Gradient clipping norm | 1.0 |

| Long Short-Term Memory | Hidden dimension | 32, 64, 128 |

| Number of layers | 1, 2, 3 |

| Batch size | 8, 16, 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.0005, 0.001, 0.002 |

| Epochs (max) | 100, 150, 200 |

| Early stopping patience | 8, 12, 16 |

| Dropout | 0.0, 0.1, 0.2 |

| Gradient clipping norm | 1.0 (conditional; only if num_layers > 1) |

| Window size | Fixed at 14 days |

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics and mathematical formulations: Model performance was evaluated using four complementary metrics that quantify different aspects of prediction quality. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures typical prediction error magnitude in grams and is robust to outliers. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), the primary metric for model ranking, penalizes larger errors and is reported in grams. Coefficient of Determination (R2, 0–1 scale) indicates the proportion of target variance explained by the model. Relative Error (percentage) enables comparison across aquaculture systems with different absolute growth scales. All metrics were calculated across a 10-fold cross-validation. Mathematical notation: n = sample size; yi = observed mean body weight; ŷi = predicted mean body weight; ȳ = mean of observed values.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics and mathematical formulations: Model performance was evaluated using four complementary metrics that quantify different aspects of prediction quality. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures typical prediction error magnitude in grams and is robust to outliers. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), the primary metric for model ranking, penalizes larger errors and is reported in grams. Coefficient of Determination (R2, 0–1 scale) indicates the proportion of target variance explained by the model. Relative Error (percentage) enables comparison across aquaculture systems with different absolute growth scales. All metrics were calculated across a 10-fold cross-validation. Mathematical notation: n = sample size; yi = observed mean body weight; ŷi = predicted mean body weight; ȳ = mean of observed values.

| Metrics | Equation | Description |

|---|

| Mean Average Error (MAE) | | MAE represents typical prediction error magnitude and is robust to outliers. |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | | RMSE emphasizes larger prediction errors and is reported in the same units as the target variable (grams). |

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | | indicates the proportion of target variance explained by the model (range: 0–1, where higher values indicate better fit). |

| Relative Error | | This metric expresses prediction error as a percentage of mean body weight, enabling comparison across systems with different absolute scales. |

Table 4.

Water quality parameter stability assessment.

Table 4.

Water quality parameter stability assessment.

| Parameter | Mean | Std | CV |

|---|

| alkalinity | 138.233 | 18.698 | 13.527 |

| salinity | 35.260 | 4.639 | 13.156 |

| do | 4.807 | 0.471 | 9.806 |

| ph | 8.190 | 0.405 | 4.941 |

| temp | 28.078 | 1.294 | 4.609 |

Table 5.

Optimal hyperparameters identified by RandomizedSearchCV (80 random iterations, 10-fold cross-validation). The table presents the hyperparameter search grid for each algorithm, with final optimal values selected to minimize RMSE on validation folds. RF: Random Forest (150 trees, max depth 15, log2 feature sampling); SVM: Support Vector Machine (RBF kernel, C = 1000, gamma = 0.001; tested alternative poly kernel with degree 2); ANN: Artificial Neural Network (128 hidden units, batch size 32, learning rate 0.005, early stopping patience 12); LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory (32 hidden dimension, two layers, batch size: 8, learning rate: 0.005, early stopping patience: 16). Window size fixed at 14 days for LSTM temporal modeling. Early stopping parameters prevent overfitting by halting training if validation loss does not improve within the specified patience epochs.

Table 5.

Optimal hyperparameters identified by RandomizedSearchCV (80 random iterations, 10-fold cross-validation). The table presents the hyperparameter search grid for each algorithm, with final optimal values selected to minimize RMSE on validation folds. RF: Random Forest (150 trees, max depth 15, log2 feature sampling); SVM: Support Vector Machine (RBF kernel, C = 1000, gamma = 0.001; tested alternative poly kernel with degree 2); ANN: Artificial Neural Network (128 hidden units, batch size 32, learning rate 0.005, early stopping patience 12); LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory (32 hidden dimension, two layers, batch size: 8, learning rate: 0.005, early stopping patience: 16). Window size fixed at 14 days for LSTM temporal modeling. Early stopping parameters prevent overfitting by halting training if validation loss does not improve within the specified patience epochs.

| Algorithm | Hyperparameters | Grid |

|---|

| Random Forest | Number of trees | 150 |

| Max depth | 15 |

| Min. samples per leaf | 2 |

| Min. samples per split | 5 |

| Feature sampling | ‘log2’ |

| Support Vector Machine | Kernel | ‘rbf’ |

| C (Regularization) | 1000 |

| Gamma (for rbf/poly) | 0.001 |

| Degree (for poly) | 2 |

| Artificial Neural Network | Hidden dimension | 128 |

| Number of hidden layers | 1 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.005 |

| Epochs (max) | 150 |

| Early stopping patience | 12 |

| Dropout | 0.5 |

| Gradient clipping norm | 1.0 |

| Long Short-Term Memory | Hidden dimension | 32 |

| Number of layers | 2 |

| Batch size | 8 |

| Learning rate | 0.005 |

| Epochs (max) | 150 |

| Early stopping patience | 16 |

| Dropout | 0.0 |

| Gradient clipping norm | 1.0 (conditional; only if num_layers > 1) |

| Window size | Fixed at 14 days |

Table 6.

Model performance metrics were evaluated via 10-fold cross-validation with 20 iterations per fold (200 total folds). RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) measured prediction deviation in kilograms; MAE (Mean Absolute Error) measured mean absolute deviation; R2 measured the proportion of variance explained (range 0–1, with 1 indicating perfect predictions). Relative Error (%) calculated as (RMSE/mean_target) × 100, representing prediction deviation as a percentage of the mean body weight. All metrics are reported as mean values across cross-validation folds. ANN achieved the lowest RMSE (1.534 g, 9.79% Relative Error), followed closely by Weighted Ensemble (1.563 g, 9.93% Relative Error, within 1.9% of ANN). Voting Ensemble also achieved a competitive performance (RMSE = 1.570 g). Stacking Ensemble underperformed other ensemble methods (RMSE = 1.834), suggesting that meta-learner combination did not improve upon simple averaging or performance-weighted averaging strategies for this dataset.

Table 6.

Model performance metrics were evaluated via 10-fold cross-validation with 20 iterations per fold (200 total folds). RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) measured prediction deviation in kilograms; MAE (Mean Absolute Error) measured mean absolute deviation; R2 measured the proportion of variance explained (range 0–1, with 1 indicating perfect predictions). Relative Error (%) calculated as (RMSE/mean_target) × 100, representing prediction deviation as a percentage of the mean body weight. All metrics are reported as mean values across cross-validation folds. ANN achieved the lowest RMSE (1.534 g, 9.79% Relative Error), followed closely by Weighted Ensemble (1.563 g, 9.93% Relative Error, within 1.9% of ANN). Voting Ensemble also achieved a competitive performance (RMSE = 1.570 g). Stacking Ensemble underperformed other ensemble methods (RMSE = 1.834), suggesting that meta-learner combination did not improve upon simple averaging or performance-weighted averaging strategies for this dataset.

| Model | RMSE (g) | MAE (g) | R-Square | Relative Error (%) | Training Time (s) |

|---|

| Random Forest | 1.791 | 1.175 | 0.932 | 11.448 | 30.866 |

| SVM | 1.642 | 1.136 | 0.943 | 11.069 | 824.191 |

| ANN | 1.534 | 1.004 | 0.950 | 9.787 | 33,719.087 |

| Voting Ensemble | 1.570 | 1.023 | 0.947 | 9.968 | 0.233 |

| Weighted Ensemble | 1.563 | 1.019 | 0.948 | 9.928 | 0.130 |

| Stacking Ensemble | 1.834 | 1.201 | 0.928 | 11.708 | 0.524 |

Table 7.

Weighted Ensemble model combination weights. Weights determined by inverse RMSE ranking across base models on the validation set. ANN achieved the lowest RMSE (1.534 g) and received the highest weight (0.358); SVM with intermediate RMSE (1.642 g) received the weight 0.335; Random Forest with the highest RMSE (1.791 g) received the lowest weight (0.307). Weights sum to approximately 1.0, enabling weighted averaging of base model predictions: Ensemble_prediction = 0.307 × RF_prediction + 0.335 × SVM_prediction + 0.358 × ANN_prediction. This weighting scheme allows the ensemble to adaptively combine base models with relative contributions proportional to their individual predictive performance.

Table 7.

Weighted Ensemble model combination weights. Weights determined by inverse RMSE ranking across base models on the validation set. ANN achieved the lowest RMSE (1.534 g) and received the highest weight (0.358); SVM with intermediate RMSE (1.642 g) received the weight 0.335; Random Forest with the highest RMSE (1.791 g) received the lowest weight (0.307). Weights sum to approximately 1.0, enabling weighted averaging of base model predictions: Ensemble_prediction = 0.307 × RF_prediction + 0.335 × SVM_prediction + 0.358 × ANN_prediction. This weighting scheme allows the ensemble to adaptively combine base models with relative contributions proportional to their individual predictive performance.

| Model | RMSE (g) | Weight |

|---|

| Random Forest | 1.791 | 0.307 |

| Support Vector Machine | 1.642 | 0.335 |

| Artificial Neural Network | 1.534 | 0.358 |

Table 8.

Cross-validation stability metrics for base models were evaluated via 10-fold GroupKFold cross-validation. RMSE_Mean represents the average RMSE across all 10 folds; RMSE_SD shows the standard deviation of RMSE values across folds; CV% (Coefficient of Variation) expresses this standard deviation as a percentage of the mean (CV% = 100 × SD/Mean), providing a scale-invariant measure of fold-to-fold variability; RMSE_95CI_Lower and RMSE_95CI_Upper are the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval calculated using the t-distribution with 9 degrees of freedom. Narrower confidence intervals indicate more consistent model performance across different pond/cycle groupings. ANN exhibited the narrowest confidence interval (0.708 g) and the lowest CV (27.7%), indicating stable predictions across folds. Random Forest and SVM showed wider confidence intervals (1.037 and 0.981 g, respectively) and higher CV values (38.0% and 40.2%), indicating greater sensitivity to fold composition.

Table 8.

Cross-validation stability metrics for base models were evaluated via 10-fold GroupKFold cross-validation. RMSE_Mean represents the average RMSE across all 10 folds; RMSE_SD shows the standard deviation of RMSE values across folds; CV% (Coefficient of Variation) expresses this standard deviation as a percentage of the mean (CV% = 100 × SD/Mean), providing a scale-invariant measure of fold-to-fold variability; RMSE_95CI_Lower and RMSE_95CI_Upper are the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval calculated using the t-distribution with 9 degrees of freedom. Narrower confidence intervals indicate more consistent model performance across different pond/cycle groupings. ANN exhibited the narrowest confidence interval (0.708 g) and the lowest CV (27.7%), indicating stable predictions across folds. Random Forest and SVM showed wider confidence intervals (1.037 and 0.981 g, respectively) and higher CV values (38.0% and 40.2%), indicating greater sensitivity to fold composition.

| Model | RMSE_Mean (g) | RMSE_SD | CV% | RMSE_95CI_Lower | RMSE_95CI_Upper |

|---|

| Random Forest | 1.907 | 0.725 | 38.014 | 1.389 | 2.426 |

| SVM | 1.704 | 0.686 | 40.249 | 1.214 | 2.195 |

| ANN | 1.787 | 0.495 | 27.689 | 1.433 | 2.141 |

Table 9.

Consensus feature importance rankings for shrimp mean body weight prediction, derived by averaging permutation importance scores across Random Forest, SVM, and Artificial Neural Network base models. The Consensus Score represents the mean importance value across all three algorithms. Features are ranked from highest (DoC, 4.213) to lowest importance (pH, 0.015) and categorized by type: Temporal (rearing cycle duration), Operational (farm management practices), Infrastructure (pond characteristics and equipment), and Environmental (water quality parameters). Harvesting-related variables (harvest_cum_kg, partial_count, partial_harvest_kg) ranked 4th, 5th, and 11th, respectively, among all features. DoC accounted for 51.1% of total consensus importance, with the top three features (DoC, feed_cum, stocking_density) collectively accounting for 81.0%.

Table 9.

Consensus feature importance rankings for shrimp mean body weight prediction, derived by averaging permutation importance scores across Random Forest, SVM, and Artificial Neural Network base models. The Consensus Score represents the mean importance value across all three algorithms. Features are ranked from highest (DoC, 4.213) to lowest importance (pH, 0.015) and categorized by type: Temporal (rearing cycle duration), Operational (farm management practices), Infrastructure (pond characteristics and equipment), and Environmental (water quality parameters). Harvesting-related variables (harvest_cum_kg, partial_count, partial_harvest_kg) ranked 4th, 5th, and 11th, respectively, among all features. DoC accounted for 51.1% of total consensus importance, with the top three features (DoC, feed_cum, stocking_density) collectively accounting for 81.0%.

| Rank | Feature | Consensus Score | Category |

|---|

| 1 | DoC | 4.213 | Temporal |

| 2 | feed_cum | 1.679 | Operational |

| 3 | stocking_density | 0.783 | Operational |

| 4 | harvest_cum_kg | 0.471 | Operational |

| 5 | partial_count | 0.342 | Operational |

| 6 | pond_size | 0.285 | Infrastructure |

| 7 | num_aerators | 0.140 | Infrastructure |

| 8 | salinity | 0.097 | Environmental |

| 9 | feed | 0.094 | Operational |

| 10 | alkalinity | 0.050 | Environmental |

| 11 | partial_harvest_kg | 0.032 | Operational |

| 12 | do | 0.020 | Environmental |

| 13 | temp | 0.019 | Environmental |

| 14 | ph | 0.015 | Environmental |

Table 10.

Feature importance by category with both total consensus scores and mean importance per feature. Mean Score represents the average consensus importance for features within each category (Total Score ÷ Number of Features). This normalization accounts for unequal category sizes: Temporal (1 feature, mean 4.213); Operational (6 features, mean 0.567, including three harvesting-related variables); Infrastructure (two features, mean 0.212); Environmental (five features, mean 0.040). The Operational category contained three harvesting-related variables (harvest_cum_kg: 0.471, partial_count: 0.342, partial_harvest_kg: 0.032), which collectively contributed 0.845 importance points to the operational category total of 3.400.

Table 10.

Feature importance by category with both total consensus scores and mean importance per feature. Mean Score represents the average consensus importance for features within each category (Total Score ÷ Number of Features). This normalization accounts for unequal category sizes: Temporal (1 feature, mean 4.213); Operational (6 features, mean 0.567, including three harvesting-related variables); Infrastructure (two features, mean 0.212); Environmental (five features, mean 0.040). The Operational category contained three harvesting-related variables (harvest_cum_kg: 0.471, partial_count: 0.342, partial_harvest_kg: 0.032), which collectively contributed 0.845 importance points to the operational category total of 3.400.

| Rank | Category | Mean Score per Feature | Total Score | Number of Features |

|---|

| 1 | Temporal | 4.213 | 4.213 | 1 |

| 2 | Operational | 0.567 | 3.400 | 6 |

| 3 | Infrastructure | 0.212 | 0.425 | 2 |

| 4 | Environmental | 0.040 | 0.201 | 5 |

Table 11.

SHAP feature importance ranking for the best-performing ANN model based on mean absolute SHAP values across 200 test samples. Mean SHAP Contribution indicates the average signed SHAP value (negative values represent features that typically decrease predictions; positive values represent features that increase predictions). Std SHAP shows the standard deviation of SHAP values across samples. Three harvesting-related variables: harvest_cum_kg (rank 5), partial_count (rank 6), and partial_harvest_kg (rank 14). DoC ranks first (Mean |SHAP| = 2.833), followed by stocking_density (1.871) and feed_cum (1.510).

Table 11.

SHAP feature importance ranking for the best-performing ANN model based on mean absolute SHAP values across 200 test samples. Mean SHAP Contribution indicates the average signed SHAP value (negative values represent features that typically decrease predictions; positive values represent features that increase predictions). Std SHAP shows the standard deviation of SHAP values across samples. Three harvesting-related variables: harvest_cum_kg (rank 5), partial_count (rank 6), and partial_harvest_kg (rank 14). DoC ranks first (Mean |SHAP| = 2.833), followed by stocking_density (1.871) and feed_cum (1.510).

| Rank | Feature | Mean |SHAP| | Mean SHAP Contribution | Std SHAP |

|---|

| 1 | DoC | 2.833 | −1.315 | 3.064 |

| 2 | stocking_density | 1.871 | 0.493 | 2.048 |

| 3 | feed_cum | 1.510 | −0.911 | 1.482 |

| 4 | pond_size | 0.675 | −0.035 | 0.766 |

| 5 | harvest_cum_kg | 0.376 | −0.349 | 0.277 |

| 6 | partial_count | 0.292 | 0.235 | 0.249 |

| 7 | num_aerators | 0.244 | 0.024 | 0.337 |

| 8 | salinity | 0.243 | −0.146 | 0.273 |

| 9 | feed | 0.221 | −0.039 | 0.323 |

| 10 | alkalinity | 0.190 | −0.164 | 0.244 |

| 11 | temp | 0.123 | −0.120 | 0.146 |

| 12 | do | 0.077 | 0.019 | 0.138 |

| 13 | ph | 0.065 | −0.064 | 0.089 |

| 14 | partial_harvest_kg | 0.014 | −0.014 | 0.090 |

Table 12.

Pearson correlation coefficients and statistical significance between features and mean body weight (mbw) across the entire dataset. Correlation coefficient (r) and two-tailed p-values are reported. Statistical significance at α = 0.05 is indicated: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, ns = not significant. Of 14 features evaluated, 13 showed statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05), while pH was not significant (p = 0.360). Three harvesting-related variables: partial_count (r = 0.760, rank 3), harvest_cum_kg (r = 0.665, rank 4), and partial_harvest_kg (r = 0.194, rank 6). Positive correlations ranged from 0.012 to 0.940, while negative correlations ranged from −0.042 to −0.196.

Table 12.

Pearson correlation coefficients and statistical significance between features and mean body weight (mbw) across the entire dataset. Correlation coefficient (r) and two-tailed p-values are reported. Statistical significance at α = 0.05 is indicated: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, ns = not significant. Of 14 features evaluated, 13 showed statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05), while pH was not significant (p = 0.360). Three harvesting-related variables: partial_count (r = 0.760, rank 3), harvest_cum_kg (r = 0.665, rank 4), and partial_harvest_kg (r = 0.194, rank 6). Positive correlations ranged from 0.012 to 0.940, while negative correlations ranged from −0.042 to −0.196.

| Feature | r | p-Value | Significant |

|---|

| DoC | 0.940 | <0.001 | *** |

| feed_cum | 0.7900 | <0.001 | *** |

| partial_count | 0.7600 | <0.001 | *** |

| harvest_cum_kg | 0.665 | <0.001 | *** |

| feed | 0.374 | <0.001 | *** |

| partial_harvest_kg | 0.194 | <0.001 | *** |

| salinity | 0.187 | <0.001 | *** |

| ph | 0.012 | 0.360 | ns |

| pond_size | −0.042 | 0.002 | ** |

| num_aerators | −0.047 | <0.001 | *** |

| stocking_density | −0.067 | <0.001 | *** |

| temp | −0.079 | <0.001 | *** |

| alkalinity | −0.145 | <0.001 | *** |

| do | −0.196 | <0.001 | *** |