Assessing Productivity and Economic Returns of Integrated Aquaculture of Red Seaweed with Shrimp and Fish During Extensive Floodings in Central Java, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

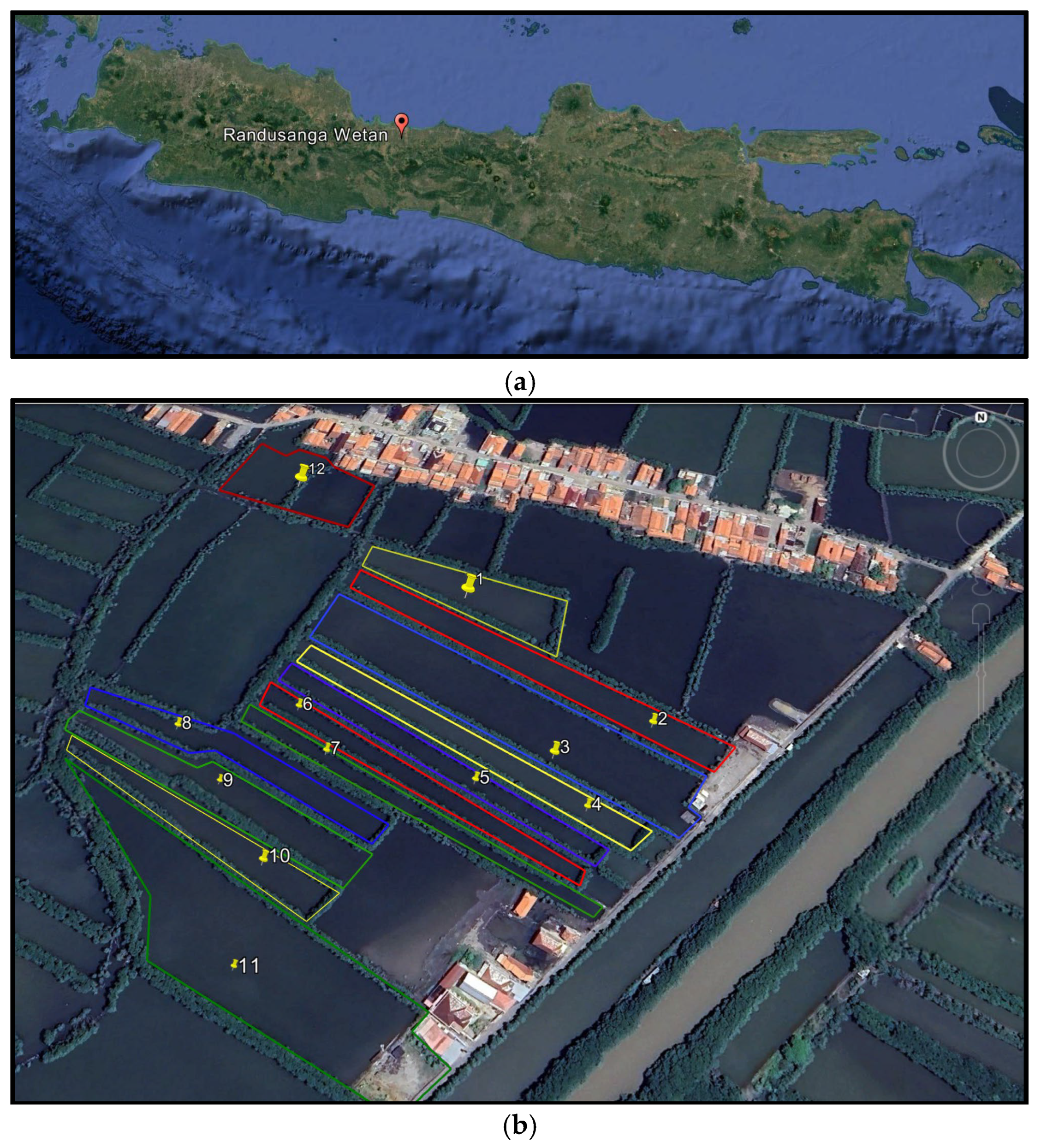

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Water Parameters

2.2. Stocking Densities

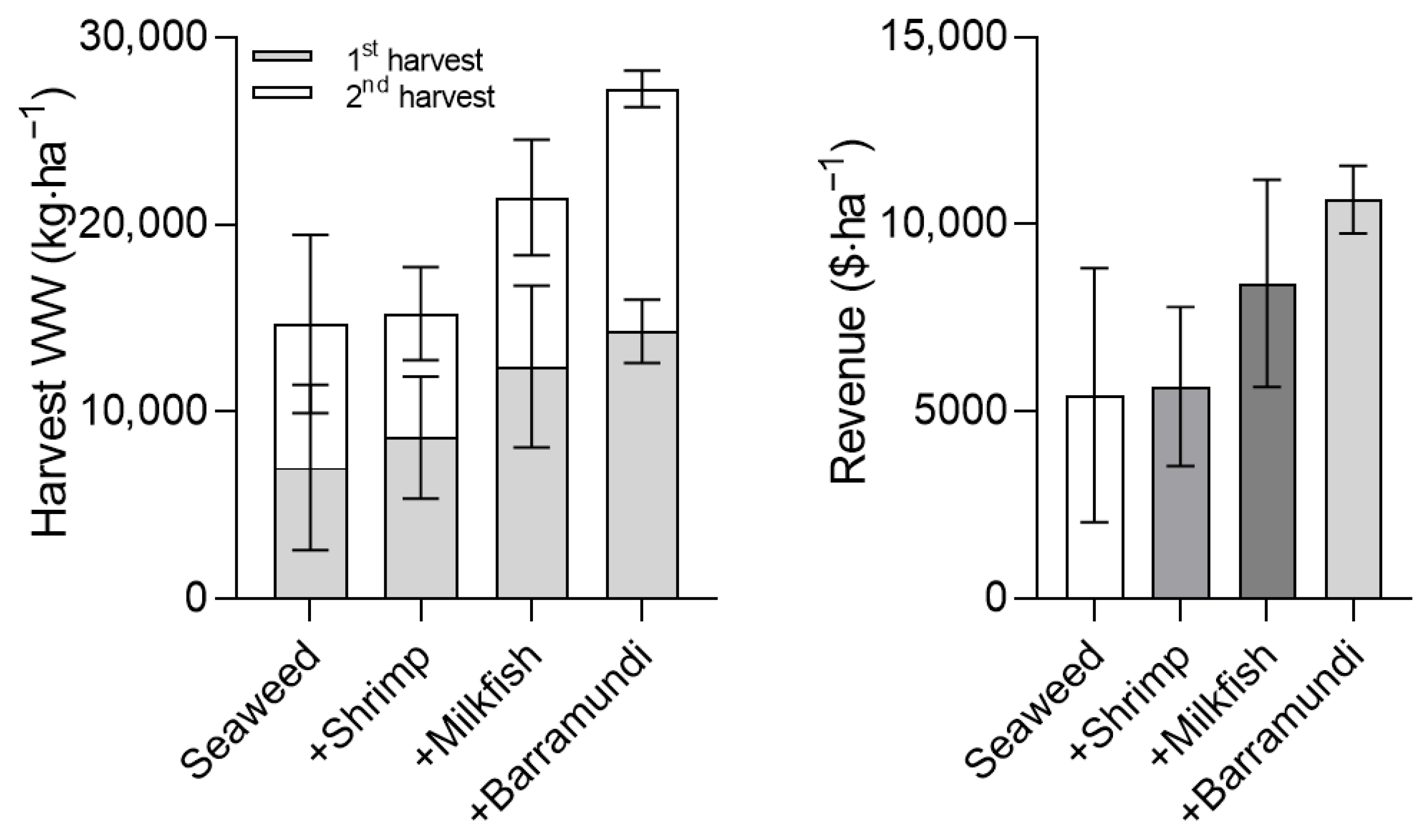

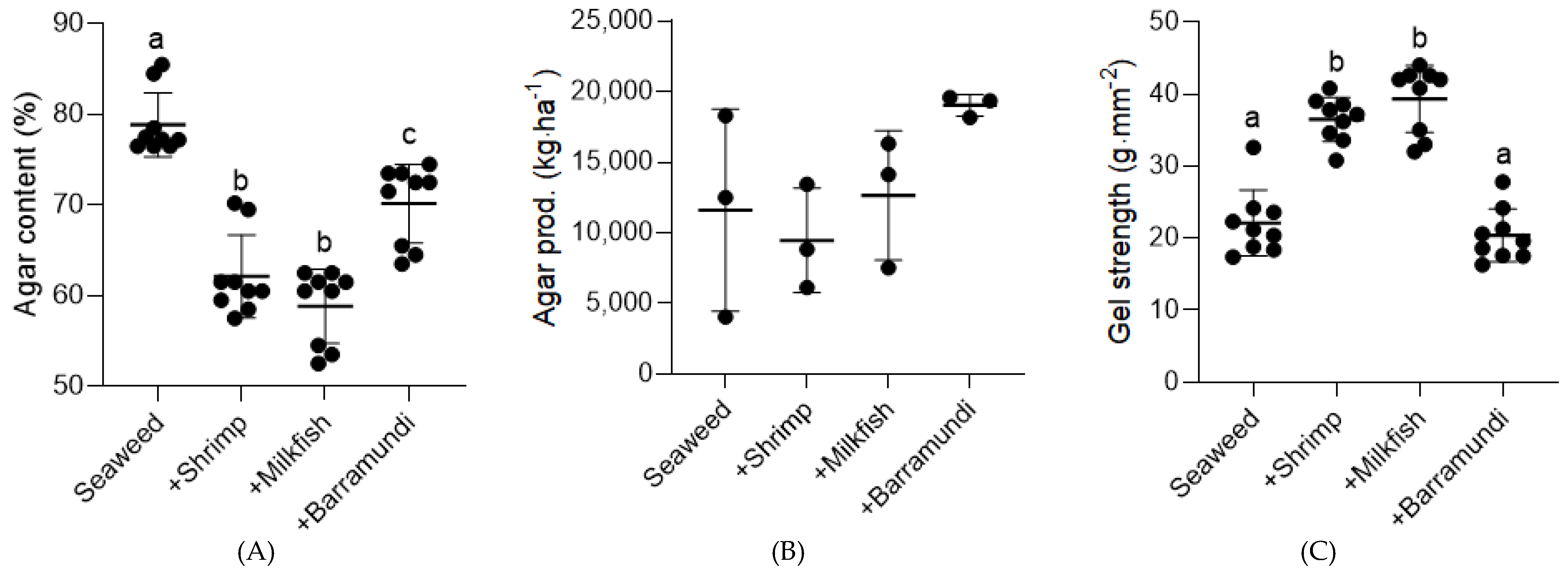

2.3. Production

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DW | Dry Weight |

| IDR | Indonesian Rupiah |

| LOD | Level of Detection |

| SGR | Specific Growth Rate |

| WW | Wet Weight |

References

- KKP (Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries). Indonesia Marine and Fisheries Book 2017; Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries: Jakarta, Indonesia; Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2017.

- Amelia, F.; Yustiati, A.; Andriani, Y. Review of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931)) farming in Indonesia: Management, operating, and development. World Sci. News 2021, 158, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, A. Community-Based Analysis of Coping with Urban Flooding: A Case Study in Semarang, Indonesia. Bachelor’s Thesis, International Institute for Geo-Information and Earth Observation, ITC, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marfai, M.A.; King, L. Coastal flood management in Semarang, Indonesia. Environ. Geol. 2008, 55, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfai, M.A.; King, L.; Sartohadi, J.; Sudrajat, S.; Budiani, S.R.; Yulianto, F. The impact of tidal flooding on a coastal community in Semarang, Indonesia. Environmentalist 2008, 28, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfai, M.A.; Almohammad, H.; Dey, S.; Susanto, B.; King, L. Coastal dynamic and shoreline mapping: Multi-sources spatial data analysis in Semarang, Indonesia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 142, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramita, A.W.; Syanfrudin, S.; Sugianto, D.N. Effect of seawater intrusion on groundwater in the Demak coastal area Indonesia: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 896, 012070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putiamini, S.; Mulyani, M.; Patria, M.P.; Soeliso, T.E.B.; Karsidi, A. Social vulnerability of coastal fish farming community to tidal (rob) flooding: A case study from Indramayu, Indonesia. J. Coast. Conserv. 2022, 26, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). King Tides Factsheet (EPA-842-F-11-010). Available online: http://water.epa.gov/type/oceb/cre/upload/king_tides_factsheet.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Lin, C.C.; Ho, C.R.; Cheng, Y.H. Interpreting and analyzing king tide in Tuvalu. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2014, 14, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaputra, A.A.; Ismunarti, D.H.; Pranowo, d.W.S. Inventarisasi Kejadian Banjir Rob Kota Semarang Periode 2012–2020. Indones. J. Oceanogr. 2022, 4, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, E.; Lubis, S.W.; Harjana, T.; Purwaningsih, A.; Risyanto Ridho, A.; Andarini, D.F.; Ratri, D.N.; Widyaningsih, R. Large-scale meteorological drivers of the extreme percipitation events and devastating floods of early February 2021 in Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAOO–What Are El Niño and La Niña. Available online: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina.html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- FAO. La Niña: Anticipatory Action and Response Plan, September–December 2024. In Mitigating the Expected Impacts of La Niña-Induced Climate Extremes on Agricltue and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Wang, G.; Santoso, A.; McPhaden, M.J.; Wu, L.; Jin, F.F.; Timmermann, A.; Collins, M.; Vecchi, G.; Lengaigne, M.; et al. Increased frequency of extreme La Niña events under greenhouse warming. Nat. Clima Change 2015, 5, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagu, N.; Lessy, M.R.; Nur, D.K. Disaster management on small islands; lessons from flash flood. J. Ilmu Lingkung. 2025, 23, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wesenbeeck, B.K.; Balke, T.; Van Eijk, P.; Tonneijck, F.; Siry, H.Y.; Rudianto, M.E.; Winterwerp, J.C. Aquaculture induced erosion of tropical coastlines throws coastal communities back to poverty. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 116, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifanti, V.B.; Novita, N.; Subarno; Tosiani, A. Mangrove deforestation and CO2 emissions in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 874, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primavera, J.H. Overcoming the impacts of aquaculture on the coastal zone. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2006, 49, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, C.; Prasad, S.N. Assessment of aquaculture impact on mangroves of Mahanadi delta (Orissa), East coast of India using remote sensing and GIS. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.M.; Bryan, K.R.; Horstman, E.M.; Mullarney, J.C. Attenuation of tides and surges by mangroves: Contrasting case studies from New Zealand. Water 2018, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyaningsih, A.P.; Deanova, A.K.; Pristiawati, C.M.; Ulumuddin, Y.I.; Kusumaningrum, L.; Setyawan, A.D. Review: Causes and impacts of anthropogenic activities on mangrove deforestation and degradation in Indonesia. Int. J. Bonorowo Wetl. 2022, 12, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Vanoye, J.A.; Diaz-Parra, O.; Márquez Vera, M.A.; Fuentes-Penna, A.; Barrera-Cámara, R.A.; Ruiz-Jaimes, M.A.; Toledo-Navarro, Y.; Bernábe-Loranca, M.B.; Simancas-Acevedo, E.; Trejo-Macotela, F.R.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Quality of Aquaculture Services in Integrated Multi-Trophic Systems. Fishes 2025, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Mahmud, M.N. Potential role of Aquaculture in advancing sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh. Aquac. Res. 2025, 2025, 6035730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Hasanuzzaman, A.F.M.; Islam, S.S.; Sarower, M.G.; Mistry, S.K.; Arafat, S.T.; Huq, K.A. Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA): Enhancing growth, production, immunological responses, and environmental management in aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, N.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Luo, J.; Christakos, G.; Wu, J. The Role of Seaweed Cultivation in Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA): The Current Status and Challenges. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e70042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muin, H.; Alias, Z.; Nor, A.; Taufek, N. Co-cultured of red hybrid tilapia and Gracilaria changii (Gracilariaceae: Rhodophyta): Effects on water quality, growth performance and algal density. Phycologia 2024, 63, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayatulbaroroh, R. Manajemen Produksi Rumput Laut Gracilaria (Gracilaria SP) Di Desa Domas, Pontang, Serang-Banten. J. Ilmiah Vastuwidya 2020, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawi, S.; Krishnan, S.; Din, M.; Arumugam, N.; Chelliapan, S. Bioremediation potential of macroalgae Gracilaria edulis and Gracilaria changii co-cultured with shrimp wastewater in an outdoor water recirculation system. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huo, Y.; Han, F.; Liu, Y.; He, P. Bioremediation using Gracilaria chouae co-cultured with Sparus macrocephalus to manage the nitrogen and phosphorous balance in an IMTA system in Xiangshan Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 91, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in Action; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeki, S.; Ariyati, R.W.; Widowati, L.L.; Bosma, R.H. The effect of three cultivation methods and two seedling types on growth, agar content and gel strength of Gracilaria verrucosa. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2018, 44, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendri, M.; Rozirwan, R.; Apri, R.; Handayani, Y. Gracilaria sp. seaweed cultivation with net floating method in traditional shrimp pond in the Dungun River of Marga Sungsang village of Banyuasin District, South Sumatera. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication, University of Galway, Ireland. 2022. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Strickland, J.-H.; Parsons, T.R. A Practical Handbook of Seawater Analysis; Fisheries Research Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1968; pp. 1–311. [Google Scholar]

- APHA/AWWA/WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Widyastuti, Y.R.; Setiadi, E. Optimization of stocking density of milkfish (Chanos chanos) in polyculture system with seaweed (Gracilaria sp.) on the traditional pond. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 744, 012099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, F.; Bosu, A.; Hasan, M.M.; Islam, M.A.; Ullah, M.R.; Khan, A.B.S.; Akhter, M.; Karim, E.; Hasan, K.R.; Mahmud, Y. Assessment of Growth Performance and Survivability of Asian Seabass (Lates calcarifer) under Different Stocking Densities in Brackish Water Ponds of South-West Coast of Bangladesh. Sustain. Aquat. Res. 2023, 2, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, R.W.; Lansbergen, R.A.; Ariyati, R.W.; Widowati, L.L.; Rejeki, S.; Debrot, A.O. Co-culture of Gracilariopsis longissima seaweed and Penaeus monodon shrimp for environmental and economic resilience in poor Southeast Asian coastal aquaculture communities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOBP. Gracilaria Production and Utilization in the Bay of Bengal; Bay of Bengal Programme for Fisheries Development: Tamil Nadu, India, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, M.E.; Martínez-Castellanos, G.; López-Méndez, M.C.; Reyes-Gonzalez, D.; González-Moreno, H.R. Production Costs and Growth Performance of Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Intensive Production Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.T.N.; Vinh, N.H.; Doan, D.T.; Lan, L.M.; Kurihara, A.; Hai, T.N. Co-culture of red seaweed Gracilaria tenuistipitata and black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon in an improved extensive pond at various stocking densities with partially reduced feed rations: A pilot-scale study. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.T.; Theuerkauf, S.J.; Rose, J.M.; Alleway, H.K.; Bricker, S.B.; Parker, M.; Petrolia, D.R.; Jones, R.C. Sustainable growth of non-fed aquaculture can generate valuable ecosystem benefits. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 53, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, L.B.; Calumpong, H.P.; Martinez-Goss, M.R.; Meñez, E.G.; Israel, A. Comparison of the performance of the agarophyte Gracilariopsis bailinae and the Milkfish Chanos chanos in mono- and biculture. In Developments in Hydrobiology; Kain, J.M., Brown, M.T., Lahaye, M., Eds.; Sixteenth International Seaweed Symposium; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhan, D.T.; Tu, N.P.C.; Tu, N.V. Comparison of growth performance, survival rate and economic efficiency of Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) intensively cultured in earthen ponds with high densities. Aquaculture 2022, 544, 738151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Bosu, A.; Hasan, M.; Yasmin, F.; Bakker, A.; Khan, S.; Akhter, M.; Ullah, R.; Karim, E.; Rashid, H.; et al. Culture techniques of seabass, Lates calcarifer in Asia: A review. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. Arch. 2023, 4, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rashdi, B.; Gallardo, W.G.; Yoon, G.; Al Masroori, H. Optimal density of Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) in combination with the Omani abalone (Haliotis mariae), brown mussel (Perna sp.), and seaweed (Ulva fasciata) in a land-based recirculating integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) system. J. Agric. Mar. Sci. 2020, 25, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapawi, R.; Zamry, A.A. Response of Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer juvenile fed with different seaweed-based diets. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2016, 44, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarudin, M.F.; Yusoff, F.; Idrus, E.S.; Aliyu-Paiko, M. Brown seaweed Sargassum polycystum as dietary supplement exhibits prebiotic potentials in Asian sea bass Lates calcarifer fingerlings. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedalhosseini, S.H.; Salati, A.P.; Mozanzadeh, M.T.; Parrish, C.C.; Shahriari, A. Effects of dietary seaweeds (Gracilaria spp. and Sargassum spp.) on growth, feed utilization, and resistance to acute hypoxia stress in juvenile Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer). Aquac. Rep. 2023, 31, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapawi, R.; Safiin, N.S.Z.; Senoo, S. Improving dietary red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty ex. P. Silva meal utilization in Asian sea bass Lates calcarifer. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 1681–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, A.; Zhang, J.; Waldron, S.; Julianto, B.; Siradjuddin, I.; Neish, I.; Nuryartono, N. Price analysis of the Indonesian carrageenan seaweed industry. Aquaculture 2022, 550, 737828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Velazco, J.M.J.; Hernández-Llamas, A.; Gomez-Muñoz, V.M. Management of stocking density, pond size, starting time of aeration, and duration of cultivation for intensive commercial production of shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Eng. 2010, 43, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Milstein, A.; Wahab, M.A.; Dewan, S. Production and economic return of shrimp aquaculture in coastal ponds of different sizes and with different management regimes. Aquac. Int. 2005, 13, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mramba, R.P.; Kahindi, E.J. Pond water quality and its relation to fish yield and disease occurrence in small-scale aquaculture in arid areas. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, P.; Imron, I.; Gunadi, B.; Van den Burg, S.; Komen, H.; Camara, M. Current status, trends, and future prospects for combining salinity tolerant tilapia and shrimp farming in Indonesia. Aquaculture 2022, 561, 738658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, T.P.; Bhatt, S.; Gokulnath, S.R.; Vasanthakumaran, K.; Solomon, J.J.; Naveen, S.K.; Selvarani, B.; Akhila, S.; Gupta, S.S.; Varghese, T. Carbon Credits and Sustainable Aquaculture: Pathway to a Greener Future. In Food Security, Nutrition and Sustainability Through Aquaculture Technologies; Sundaray, J.K., Rather, M.A., Ahmad, I., Amin, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Mean +/− SD | Min | Max | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 29.5 ± 1.1 | 24.2 | 33.7 | 29.5 |

| Salinity (‰) | 25.0 ± 3.9 | 13.1 | 32.5 | 24.9 |

| pH | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 7.0 | 8.9 | 7.7 |

| Chl-A (µg·L−1) | 1.82 ± 1.27 | 0.06 | 10.76 | 1.87 |

| Nitrate (mg·L−1) | 0.468 ± 0.268 | 0.035 | 1.197 | 0.495 |

| Phosphate (mg·L−1) | 0.34 ± 0.39 | 0.015 | 1.281 | 0.051 |

| Seaweed | Shrimp | Milkfish | Barramundi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seaweed | Stocking (kg·ha−1) | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| First harvest WW (kg·ha−1) | 7017 ± 4416 | 8631 ± 3261 | 12,403 ± 4323 | 14,297 ± 1689 | |

| Second harvest WW (kg·ha−1) | 7681 ± 4769 | 6615 ± 2493 | 9045 ± 3090 | 12,965 ± 977 | |

| Total harvest WW (kg·ha−1) | 14,699 ± 9182 | 15,246 ± 5746 | 21,447 ± 7413 | 27,263 ± 2661 | |

| Total harvest DW (kg·ha−1) | 2100 ± 1312 | 2178 ± 821 | 3064 ± 1059 | 3895 ± 380 | |

| SGR | 2.10 ± 0.64 | 2.23 ± 0.33 | 2.51 ± 0.33 | 2.75 ± 0.08 | |

| Price per kg DW | $ 0.37 | $ 0.37 | $ 0.37 | $ 0.37 | |

| Mean yield ($·kg−1) | $ 777 ± 485 | $ 805 ± 304 | $ 1134 ± 392 | $ 1441 ± 141 | |

| Added Commodity | W0 (g) | 0.23 ± 0.00 | 4.51 ± 0.07 | 28.10 ± 1.25 | |

| W120 (g) | 14.10 ± 0.22 | 131.53 ± 83.35 | 301.26 ± 12.90 | ||

| SGR (%) | 3.42 ± 0.01 | 2.71 ± 0.49 | 1.98 ± 0.05 | ||

| Harvest (kg·ha−1) | 49.6 ± 11.6 | 315.2 ± 75.2 | 283.5 ± 49.0 | ||

| Price per kg | $ 0.54 | $ 1.55 | $ 2.02 | ||

| Mean yield ($·ha−1) | $ 27 ± 6 | $ 488 ± 117 | $ 573 ± 99 | ||

| Total revenue ($·ha−1) | $ 777 ± 485 | $ 832 ± 308 | $ 1622 ± 429 | $ 2014 ± 85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nauta, R.W.; Widowati, L.L.; Ariyati, R.W.; Rejeki, S.; Debrot, A.O. Assessing Productivity and Economic Returns of Integrated Aquaculture of Red Seaweed with Shrimp and Fish During Extensive Floodings in Central Java, Indonesia. Aquac. J. 2025, 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5040026

Nauta RW, Widowati LL, Ariyati RW, Rejeki S, Debrot AO. Assessing Productivity and Economic Returns of Integrated Aquaculture of Red Seaweed with Shrimp and Fish During Extensive Floodings in Central Java, Indonesia. Aquaculture Journal. 2025; 5(4):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5040026

Chicago/Turabian StyleNauta, Reindert Wieger, Lestari Lakhsmi Widowati, Restiana Wisnu Ariyati, Sri Rejeki, and Adolphe Oscar Debrot. 2025. "Assessing Productivity and Economic Returns of Integrated Aquaculture of Red Seaweed with Shrimp and Fish During Extensive Floodings in Central Java, Indonesia" Aquaculture Journal 5, no. 4: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5040026

APA StyleNauta, R. W., Widowati, L. L., Ariyati, R. W., Rejeki, S., & Debrot, A. O. (2025). Assessing Productivity and Economic Returns of Integrated Aquaculture of Red Seaweed with Shrimp and Fish During Extensive Floodings in Central Java, Indonesia. Aquaculture Journal, 5(4), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5040026