1. Introduction

Hamstring strain injury is a common musculoskeletal condition that affects both active individuals and professional athletes [

1]. Many risk factors for hamstring injury have been identified in the literature. Nevertheless, only a few of them are based on evidence, while the majority are based on theory and can be classified into modifiable factors and non-modifiable factors [

2]. Modifiable risk factors include muscle shortening, lack of muscle flexibility, discrepancy in muscle strength between one limb and another, insufficient warm-up, fatigue, lower back injury, and increased muscle neural tension. Non-modifiable risk factors include muscle composition, age, ethnicity, and previous injuries [

3]. These injuries account for more than 39% of all recorded sports injuries and can result in prolonged time lost due to the injury, ranging from 17 to 90 days, and therefore requiring extensive therapeutic intervention and rehabilitation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Furthermore, 12–63% of individuals who suffer a hamstring injury are susceptible to recurrence [

4,

5,

6,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Moreover, one third of these recurrences occur within one year of the initial injury and are often more severe [

16]. The high rate of hamstring injury recurrence can be attributed to insufficient rehabilitation interventions, failure to address the true etiology of the injury, or failure to meet the objective criteria for return to sport (RTS) [

1,

17,

18].

Examination of athletes with hamstring injury has traditionally relied on combinations of pain with palpation of the injured area, traditional manual muscle testing, passive straight leg raises testing, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and isokinetic testing. However, the studies on diagnostic accuracy of palpation, traditional manual muscle testing, and leg raises testing have not provided sufficient information to quantify the clinical ability of these tests to differentiate between those with and without confirmed hamstring injury. In addition, some of these tests have been described only for assessment of readiness for RTS [

19]. MRI and ultrasonography (US) are considered the criterion reference standards for diagnosis of hamstring injuries. However, both MRI and US are not practical alternatives for diagnosis of hamstring injury often due to costs associated with these diagnostic tests [

19]. Other methods are commonly used in a field setting [

20,

21] to assess RTS or injury severity.

The Nordic hamstring exercise is widely used to assess the strength of the hamstring muscles and is characterized by a downward movement of the body until the moment the participant is no longer able to sustain the movement. This specific moment, often called break-point angle (BPA), is represented by the angle that the trunk makes with the ground and has a significant relationship with peak torque, when evaluated in an isokinetic movement [

22]. Additionally, it has a meaningful correlation between eccentric knee flexion strength and knee flexion angle [

23]. Therefore, the moment of muscle failure, determined by the BPA becomes fundamental for estimating hamstring strength.

Recurrence suggests a significant gap in the effectiveness of current rehabilitation and prevention strategies, as well as evaluation procedures [

1,

24,

25]. Therefore, amongst other factors, the need for simplified, accurate, and accessible assessment procedures is essential to identify risk factors, and how to monitor the progression of rehabilitation and effectively implement preventive strategies.

In this context, smartphone-based applications have emerged as a promising solution. Portability, low cost, wide availability, and the fact that the assessments can be carried out in real-time, with quick access to the results [

22], offer significant advantages for physical and clinical assessment. This is particularly important in sports environments where specialized equipment may not be readily available and is usually intrusive, difficult to transport, and complicated to operate [

26].

My Jump Lab is a smartphone application (app) that has been established as a validated method for assessing jump height [

27] or sprint performance [

28]. It has embedded a sub-application called Nordics, which is used for assessing the Nordic hamstring exercise and estimating the BPA. This angle is highly related to hamstring eccentric strength, and My Jump Lab has been confirmed as a valid and reliable instrument for its determination [

29]. Also, based on the angle and some previous measurements, it can estimate torque (rotational force) at that point [

30].

Peak torque analysis is an important tool in both the prevention of hamstring injuries and the assessment of an athlete’s readiness to RTS, though it should always be interpreted in context and alongside other measures. This type of assessment helps to identify neuromuscular imbalances and residual weakness. In practice, asymmetrical thresholds can guide decision-making RTS clearance. However, it should integrate other types of evaluations (functional testing or clinical evaluation), since peak torque reflects muscle performance in a controlled setting that may not fully replicate the high-speed, lengthened-muscle conditions of a specific sport context point [

31,

32].

Some authors have already demonstrated the validity of this type of method for evaluating other physical assessment parameters, such as asymmetry and muscle fatigue in the lower limbs [

22,

33], gait/running asymmetry [

34], and muscle strength levels [

35]. One study used a setup identical to our study to evaluate the validity of a portable device for assessing hamstring eccentric strength, with moderate correlation with the isokinetic dynamometer [

36].

However, despite the potential of these technologies, there is still a scarcity of data available on the efficiency and applicability of the many applications that are available on the market. In fact, the validity and reliability of many smartphone applications, which assess various components of physical assessment, is still relatively unclear [

37,

38], as they have not been tested and compared with gold-standard equipment [

39]. These applications, whose validity is unknown, include those that assess hamstring injury parameters.

Hence, there is a distinct gap in the existing literature investigating the development and validation of mobile applications as assessment and monitoring tools in general, specifically for hamstring injuries, and there is a need to validate practical and accessible tools and solutions in this field [

33,

34,

35,

37,

38].

The aim of this study is to establish the validity and reliability of the peak torque estimate made by the My Jump Lab app in the Nordic hamstring exercise by comparing it with the values obtained by an isokinetic dynamometer in recreational athletes.

If the application is valid, it will be very useful in the field, as it will allow for more regular monitoring of the hamstring muscles, thereby helping to prevent injury. We hypothesized that the My Jump Lab app would demonstrate good validity and reliability compared to isokinetic dynamometry for assessing eccentric hamstring peak torque.

2. Results

A total of twenty-seven participants (age = 23.15 ± 2.16 years; height = 177.86 ± 7.1 cm; weight = 76.93 ± 12.42 kg) which met the inclusion criteria took part in the present study.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics related to the average values obtained with the My Jump Lab app (ANAMED1 corresponds to the assessments performed by evaluator 1, while ANAMED2 reflects the same procedure carried out by evaluator 2), as well as the isokinetic assessments.

In all three assessments that were evaluated, the sample consisted of 27 participants, with no missing data. Regarding ANAMED1, the mean value recorded was 394 ± 70.6 Nm, while for ANAMED2 the mean results were 395 ± 71.6 Nm. The range of values could indicate consistency in the measurements for both evaluators. Finally, the dynamometry results revealed a significantly lower mean of 166 ± 41.1 Nm, reflecting reduced force or torque recorded in this specific assessment. The standard deviation suggested less dispersion compared to the other analyses.

Table 2 displays the Pearson correlation coefficients between the values obtained in the two ANAMED assessments (ANAMED1 and ANAMED2) and the dynamometry results, all expressed in Newton-meters (Nm). A nearly perfect positive correlation was observed between ANAMED1 and ANAMED2 (r = 0.999), indicating a very high level of consistency. This correlation was statistically significant (

p < 0.001). Additionally, both ANAMED measurements showed strong positive correlations with dynamometry values and were statistically significant (

p < 0.001).

The reliability analysis (

Table 3) between ANAMED 1 and the dynamometry test revealed a value of 0.7599 and a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.5367 to 0.876. The results on this table show good agreement between raters, indicating high repeatability of the app measurements.

When looking at the results between ANAMED 2 and the isokinetic assessment, intraclass coefficient (ICC) value was 0.7574, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.5320 to 0.874. Like evaluator 1, these results reveal good reliability and consistent agreement between ANAMED 2 and isokinetic dynamometry.

ANAMED measurements (ANAMED 1 and ANAMED 2) demonstrated excellent consistency and reproducibility. The coefficient of variation (CV) was remarkably low at 0.66%, indicating high measurement stability across the two time points. The standard error of measurement (SEM) was 2.6019 Nm, while the standard error of the estimate (SEE), and the standard error of prediction (SEP) were 3.6773 Nm and 5.2022 Nm, respectively, reflecting minimal random variability. The very low SEM reinforces the good agreement between the two evaluators using the same tool, underscoring its reproducibility.

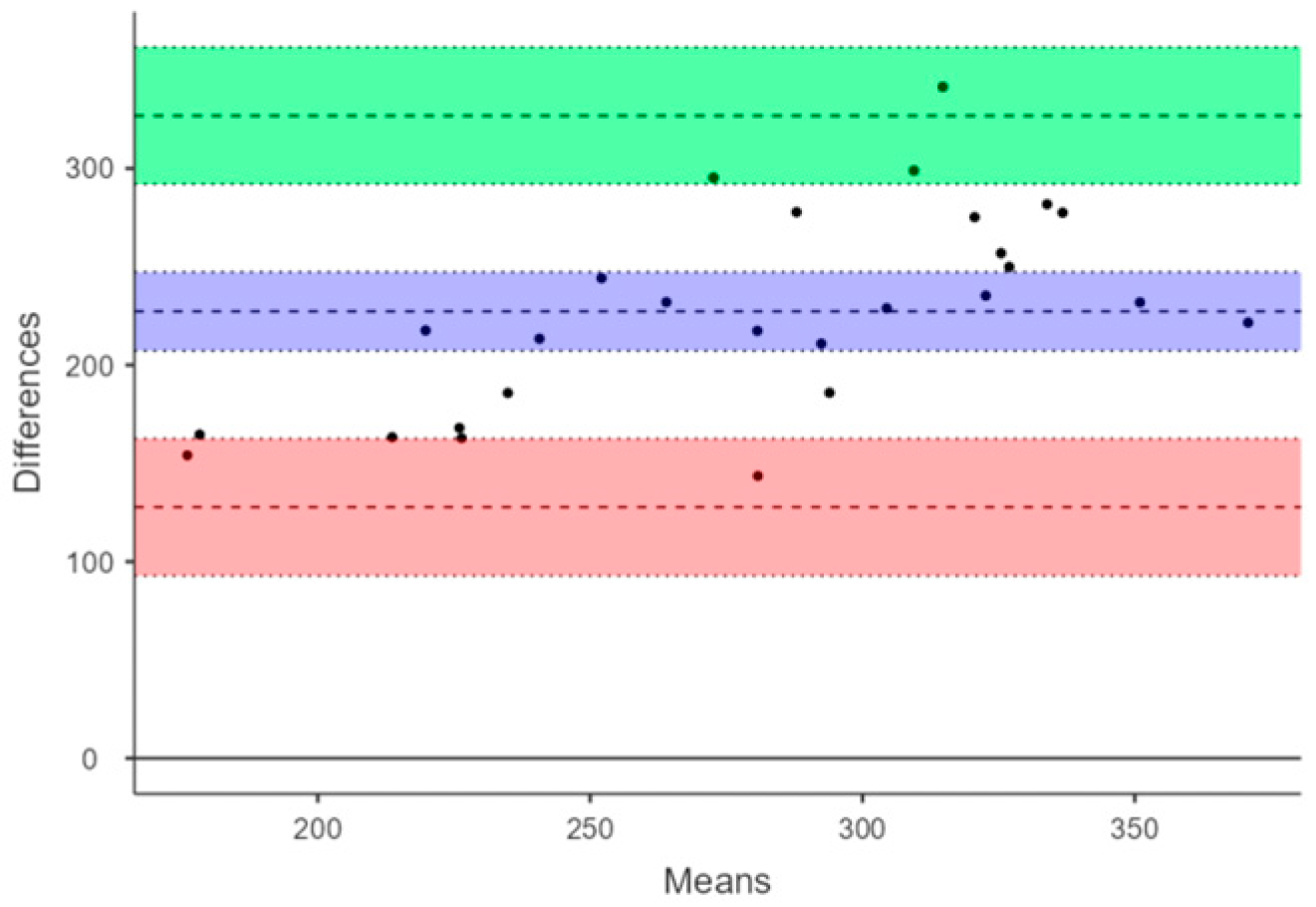

Figure 1 presents the Blandi–Alman plot between ANAMED 1 and isokinetic assessment.

The mean bias between the two methods was 227 Nm, indicating that, on average, the value obtained with ANAMED 1 was higher than those recorded by the dynamometer. The 95% confidence interval for the bias ranged from 207.2 Nm to 247 Nm, confirming the presence of a systematic difference between the two methods. The limits of agreement ranged from 128 Nm (lower limit) to 327 Nm (upper limit), with respective confidence intervals of 92.9 Nm to 162 Nm and 292.1 Nm to 362 Nm. These wide limits suggest considerable variability in the differences between the two measurements across individuals.

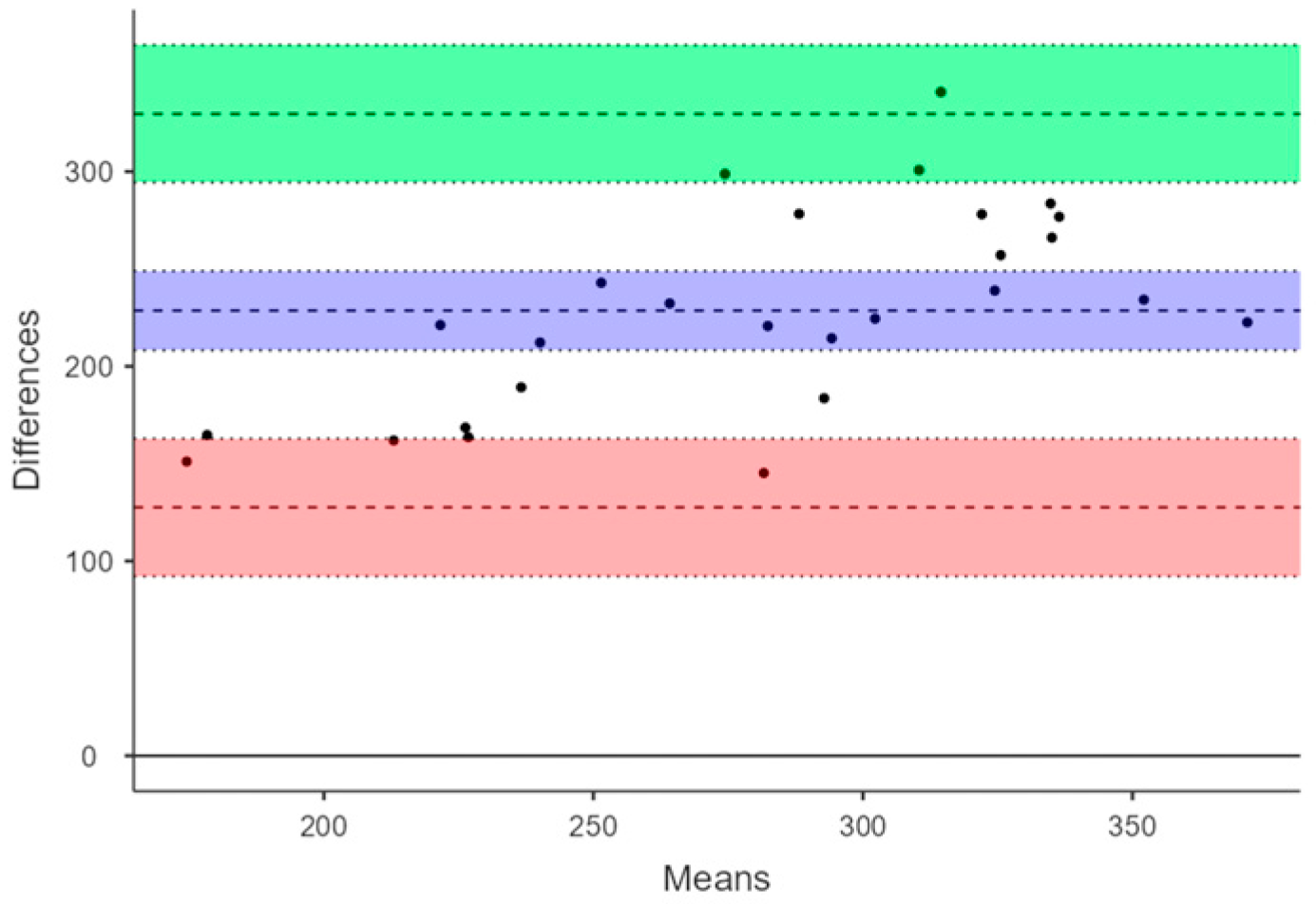

The Bland–Altman analysis comparing ANAMED 2 with the dynamometer (

Figure 2) revealed a mean bias of 229 Nm, indicating a systematic overestimation of values by ANAMED 2. In other words, the measurements obtained using ANAMED 2 were, on average, 229 Nm higher than those recorded by the reference device. The 95% confidence interval for the bias ranged from 208.2 Nm to 249 Nm, reinforcing the presence of a consistent and statistically significant discrepancy between the two methods. The limits of agreement were calculated to range from 128 Nm (lower limit) to 330 Nm (upper limit), with respective confidence intervals of 92.2 Nm to 163 Nm and 294.4 Nm to 365 Nm.

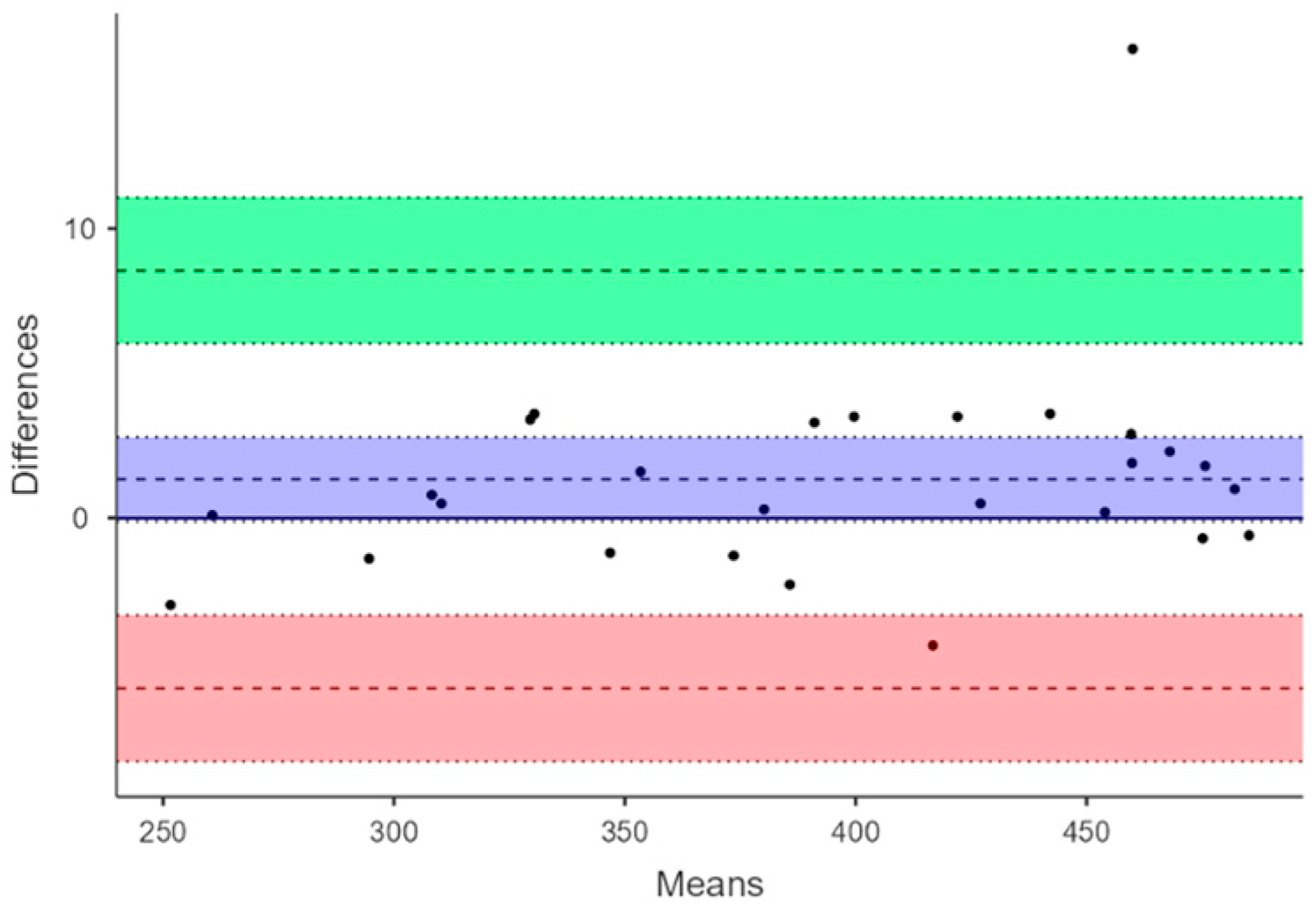

The plot comparison between ANAMED1 and ANAMED2 (

Figure 3) showed a very small mean bias of 1.34 Nm, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.12 to 2.79 Nm, indicating a high level of agreement between the two raters. The limits of the agreement ranged from −5.87 Nm (lower limit) to 8.55 Nm (upper limit).

3. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the validity and reliability of the My Jump Lab smartphone application for measuring peak torque of the hamstring muscles during the Nordic exercise, using isokinetic dynamometry as a reference instrument. This study represents, to date, the first study to specifically validate the peak torque estimated by the My Jump Lab app, thus filling an important gap identified in the literature, as highlighted in the introduction. Until now, most studies [

39,

40,

41,

42] have focused on assessing the BPA during the Nordic exercises, using different mobile applications, but none had directly validated the estimate of eccentric force expressed in the torque obtained by this application.

Among the main findings, the high inter-rater reliability stands out, evidenced by an ICC of 0.999 between ANAMED1 and ANAMED2. In addition, the application demonstrated good relative validity, with ICC values of 0.7599 for ANAMED1 and 0.7574 for ANAMED2 in relation to the dynamometer, and a significant Pearson correlation (r ≈ 0.705 for both comparisons with the dynamometer, p < 0.001). However, a substantial systematic bias was identified, with the values obtained by the application exceeding the dynamometer values.

It is also important to highlight the CV values, used as an additional indicator of the reliability of the methods. The CV between ANAMED1 and ANAMED2 reinforces the exceptional consistency of the measurements between evaluators. On the other hand, the CV values between ANAMED1 and the dynamometer and between ANAMED2 and the dynamometer are slightly above the 10% threshold, traditionally considered indicative of good reliability. However, several authors report that CV values up to 15% are still considered acceptable [

43], in muscle performance and sports science studies, especially in contexts where small individual variations are expected. In this sense, the CV values obtained in the present study can be classified as indicative of acceptable to good reliability, reinforcing the robustness of the observed results. This interpretation is further supported by the SEM values between the application and the dynamometer. Although acceptable, these values should be considered when analyzing individual changes over time, especially in assessments of progress or response to interventions.

In this study, the My Jump Lab application demonstrated good relative validity, reflected in statistically significant correlations with the dynamometer. This validity is especially relevant in the context of functional assessment of recreational athletes, where measuring eccentric hamstring strength is essential for the screening for injury risk, monitoring training, and returning to sports. Although the app systematically overestimated torque compared with dynamometry, the strong correlation and low inter-rater error support its use for tracking relative changes rather than absolute torque values.

Multiple indicators were used for assessing reliability, with great correlation between evaluators. On the other hand, when comparing the application with the dynamometer, although reliability remained within an acceptable range, the SEM values were higher. The heterogeneity of our sample may have led to greater variability in the measurements and, as a result, a larger standard error of measurement. These results may have relevant implications for the interpretation of small clinical changes, especially in individual assessments. Given the SEM of ~36 Nm, only changes exceeding this threshold should be interpreted as true performance variation. Thus, although the relative reliability between the methods is adequate, the magnitude of the SEM should be considered when making clinical decisions based on absolute values.

It is important to highlight the different comparison methods used, which are related to the biomechanical differences in the type of measurement performed, which could account for difference in the results. Torque output was measured with two different methods and positions. The My Jump Lab application evaluates the Nordic exercise bilaterally, capturing the combined eccentric force of both lower limbs. In contrast, isokinetic dynamometry performs a unilateral assessment, usually of the dominant leg. This difference may partly explain the systematic bias identified in the Bland–Altman analysis. In addition, it is also important to consider that the method of calculating torque differs substantially between the methods. The My Jump Lab application calculates torque based on a classic formula (T = body mass × lever length × sine of the angle of the stopping point), which implies a simplification of variables and theoretical assumptions. On the other hand, the isokinetic dynamometry assessment directly measures the torque exerted during movement, in a continuous and controlled manner, with well-defined parameters of speed and joint position. Opposingly, it was not feasible to establish a predetermined velocity in the Nordic exercise. Given that velocity could affect torque production, this also may help to explain the differences in torque output by the two methods used.

Another contrast is the difference in the position and execution of the movement between the two methods, which may influence muscle recruitment, and the magnitude of the force produced, since it has been reported that peak torque output is generally higher in the seated position [

43]. Therefore, the difference in device analysis as well as assessment position could explain the results between My Jump App and the isokinetic evaluation.

A high systematic bias was identified in our study when comparing the results. This difference can be attributed to the difference between bilateral (smartphone application) and unilateral (dynamometer) measurements, which is an aspect not controlled in previous studies.

It could suggest that, although the methods are correlated, they do not produce directly interchangeable values. Despite this limitation, the dispersion of differences remained within margins that are considered clinically acceptable for practical use, especially in contexts where the objective is to monitor changes in muscle performance over time, rather than to obtain absolute measurements of strength.

The methodological differences previously mentioned could be considered as potential causes of the systematic bias identified. They reinforce the need to use the application mainly for relative monitoring purposes (e.g., trends over time) and not as a direct substitute for dynamometry in obtaining absolute values.

The results of this study, which evaluated the validity and reliability of the My Jump Lab application for measuring eccentric peak torque of the hamstrings during the Nordic exercise, reveal similarities and relevant differences in relation to the existing literature. Støve et al. [

36] compared isokinetic assessment with a portable device for assessing Nordic hamstring strength. The results of the study revealed moderate agreement between equipments, with excellent reliability, which is similar to ours. Another study by Vercelli et al. (2020) [

44] analyzed the reproducibility of the DrGoniometer application in measuring the break-point angle during the Nordic exercise and observed high inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.82–0.89), with low SEM (2°). Although the parameter evaluated was different (angle vs. torque), both studies demonstrated high consistency between evaluators when using mobile tools in the context of the Nordic exercise. The present study showed even higher inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.999), even in different measurement contexts. In turn, Soga et al. [

40] explored the validity of an app for measuring the break-point angle, finding a strong correlation (r = 0.75) with two-dimensional analysis and perfect reliability (ICC = 1.00), with no significant differences between methods. As in the present study, limitations such as the use of only one session and a small sample size were pointed out, which affect the generalization of the results. With a similar methodology to our study, Lee et al. [

42] employed video analysis of the Nordic Exercise and compared it with isokinetic dynamometry assessment. The authors reported correlations between 0.58 and 0.88, like those reported in the present study. Additionally, the authors also reported that the BPA was highly correlated with the isokinetic peak torque, thus providing evidence on the methods used in our study.

The results obtained in our study are encouraging and provided support for the use of the application as a viable tool for measuring hamstring eccentric strength, both in clinical and sports settings, especially in situations where the use of isokinetic dynamometry is not possible or feasible.

3.1. Practical Applications

The My Jump Lab application offers several advantages that are relevant to clinical and sports practice. Its portability, low cost, and ease of use make it particularly suitable for field settings, such as sports clubs, gyms, or clinics with limited resources. In addition, it provides real-time results, which facilitates immediate decision-making in the management and monitoring of athletes. Another positive point is its high inter-rater reliability, which ensures consistency of results regardless of the professional responsible for the assessment. The application is also useful for monitoring the evolution of eccentric hamstring strength over time and is particularly suitable for injury prevention programs or gradual return to sports programs. However, the results of this study indicate that its use by practitioners, coaches or physical therapy professionals should focus on the assessment of relative progress and individual trends, rather than obtaining absolute values. This is due to the fact that systematic bias was identified in the measurements compared to the isokinetic dynamometer.

3.2. Study Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the comparison between bilateral measurements, performed using the app, and unilateral measurements, performed with the dynamometer, limits the direct comparability of the values obtained. In addition, the distinct way in which torque was estimated in each method may introduce additional discrepancies. The sample used consisted exclusively of recreational athletes, which limits the generalization of the results to other populations, namely elite athletes or individuals in rehabilitation. Data collection was performed in a single session, which makes it impossible to analyze intersession reliability, limiting the understanding of the temporal stability of the measurements. Finally, the present study was conducted in a controlled setting (laboratory) and its transfer to different contexts (e.g., training settings) should be made with caution.

3.3. Suggestions for Future Research

To deepen knowledge about the My Jump Lab application and explore its full potential, several directions for future research are suggested. First, it would be pertinent to compare the values obtained by the application with the bilateral sum of dynamometry data to ensure greater biomechanical equivalence between the methods. In addition, conducting intersession test–retest studies would allow for the evaluation of measurement stability at different times, an essential factor for more robust clinical validations. Furthermore, we propose the inclusion of complementary devices such as NordBord, which allows for the performance of classic Nordic exercises while dynamometers positioned on each lower limb individually measure the force applied [

44]. This approach would allow for a more accurate analysis of the distribution of forces between the limbs, contributing to the validation of the bilateral measurement provided by the My Jump Lab application. The application should also be tested in clinical populations and high-performance athletes to expand the applicability of its results. Integration with additional technologies, such as three-dimensional motion analysis or surface electromyography (EMG), could enrich the cross-validation process. Finally, it will be essential to investigate the sensitivity of the application to specific training programs to confirm whether it can detect real improvements in eccentric strength over time with accuracy and reproducibility. Future studies should automate break-point detection to minimize observer bias and include test–retest reliability across sessions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

At the laboratory of the Egas Moniz Physical Therapy Clinic, participants were greeted and oriented to the process of data collection and informed consent. The informed consent form, which described all the stages they would be put through during the study, was delivered a week before the participants went to the testing site to ensure that they had time to reflect on their participation and did not feel pressured to accept. After signing the informed consent form, body mass, height and age data were collected from each participant. It is essential to note that, to calculate peak torque with the My Jump Lab app, it asked for data on the height from the knee to the head, so it was necessary to collect this data as well.

Afterwards, the participants began a warm-up, which consisted of dynamic movements such as leg swings, lunges, and squats, with two sets of ten repetitions each [

40]. When the warm-up was over, the order in which the exercises were performed (Nordic or isokinetic movement) was randomized. Participants which were assigned an odd number (S1, S3…) started with Nordics and participants with even numbers (S2, S4,…) started with the isokinetic assessment.

The isokinetic assessment was performed with the isokinetic dynamometer (Humac Norm, Stoughton, MA, USA). This guaranteed impartial selection of participants to start with one of the exercises, which ensured the integrity of the study results.

4.2. Study Settings

The study was carried out in the laboratory of the physiotherapy clinic at the Egas Moniz School of Health and Science, and each subject went to the laboratory once to carry out the two assessments [

41]. Data collection began in October 2024 and ended in December 2024.

4.3. Eligibility Criteria

Regarding the inclusion criteria, participants of both sexes had to be aged between 18 and 35, as has been performed in previous studies [

40,

41,

42,

45], having to be considered recreational athletes, meaning that they exercise >4 h/week for pleasure, to keep fit or for unregulated competitions [

45]. Participants were excluded if (a) they were unable to complete the Nordic exercise due to pain or physical incapacity [

40,

41]; (b) if they had any type of lower limb injury in the last six months [

23,

42]; (c) inability to walk normally, as this may indicate possible motor or muscular deficiencies that could compromise the validity of the test results (

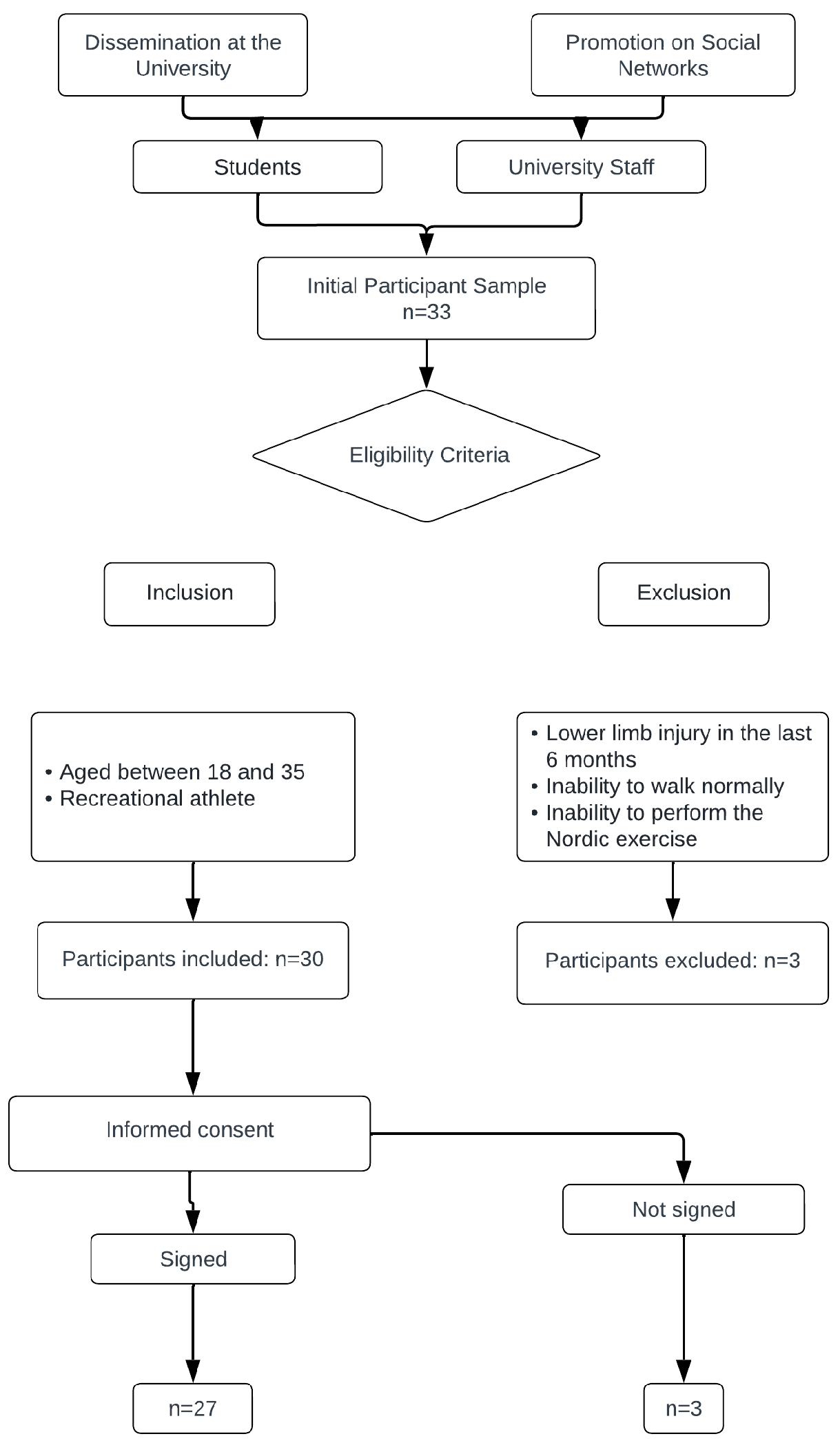

Figure 4).

4.4. Recruitment Plan

The recruitment plan included the distribution of flyers at the Egas Moniz School of Health and Science, publicizing the study on social networks and interacting socially with students and adults at the school. If an individual showed interest, a QR code was made available on the flyer which would direct them to an anonymous approval form for participation in the study, where they will be questioned according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, to understand whether they are suitable to take part in the study.

4.5. Sample Size Calculation

For achieving the purpose of this study, a sample size of 27 participants (accounting for a 10% dropout) was determined using the calculation to detect a minimum accepted ICC of 0.9, an alpha error probability set at 0.05, and a power (1-Beta) of 0.9 [

46].

4.6. Data Collection and Management

A week before data collection, an informed consent form was delivered to the participants, along with an explication of all procedures. Afterwards, biometric data collection was conducted in a standardized way, using a digital scale (Omron, Kyoto, Japan) and a tape measure (Stanley, New Britain, CT, USA). Additionally, the distance from the knee to the head (lever), as required by My Jump Lab for torque estimation, was measured with a measuring tape (measured in cm), where one end was placed on the lateral condyle of the knee and the other end on the highest point of the head (measured on a vertical line).

Data collection was preceded by three minutes of dynamic movements such as leg swings, lunges, and squats, with two sets of ten repetitions each [

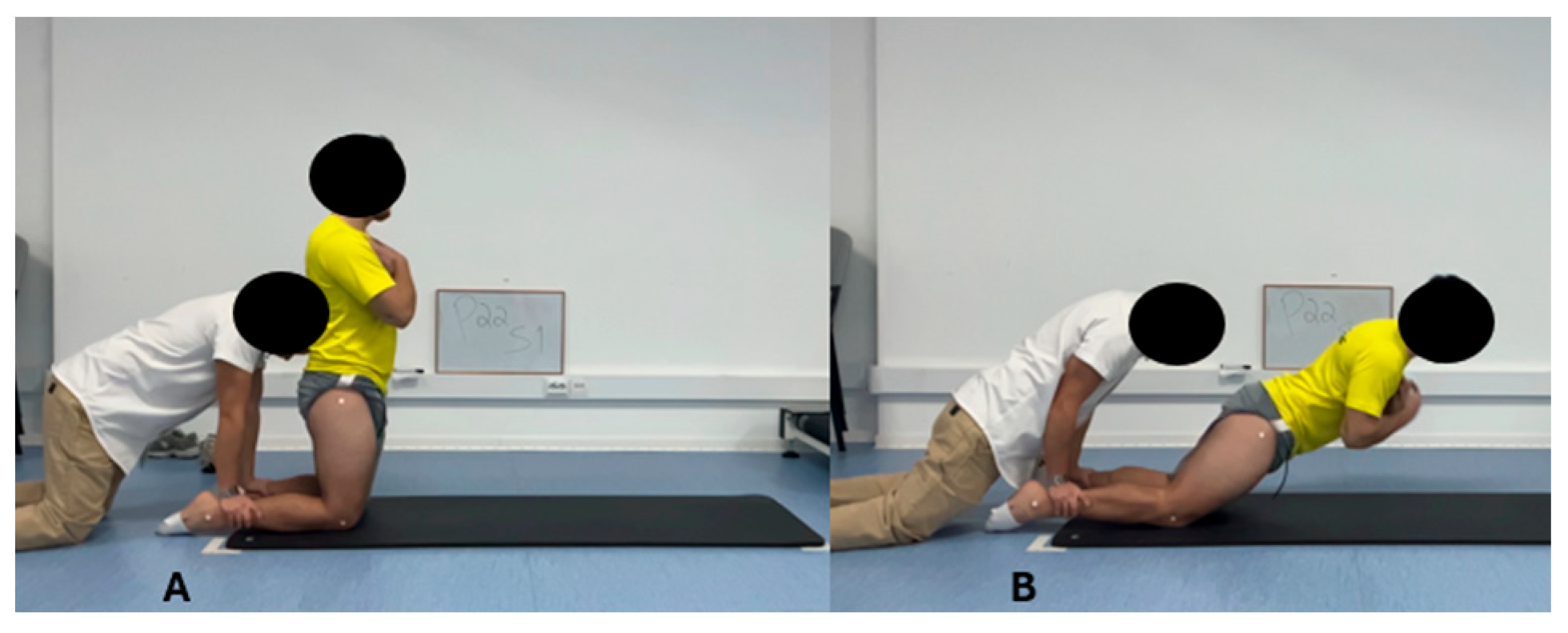

40]. After the warming up, three pieces of Kinesiotape (markers) were placed on the participants to serve as anatomical references for break-point angle determination with the My Jump Lab app. The markers were placed on the external malleolus, the lateral epicondyle of the knee, and the greater trochanter of the femur. These markers were approximately 1.5 cm in size. To perform the Nordic exercise, participants were asked to assume the starting position, by kneeling on a soft surface with their knees aligned with their pelvic girdle and crossing their arms over their chest. A physical therapist kneeled behind the participants and held the lower part of their legs with both hands, above the ankle joint, pushing them to the floor with their body weight. During the exercise, the participants’ body was completely aligned, from head to knee. Participants were asked to lean slowly forward, performing only knee extension, trying to maintain the position with the thigh muscles and at a constant speed. When they could no longer hold the position, the participants were instructed to remove their hands from their shoulders and place them into a push-up position, to support the fall (

Figure 5) [

44].

Participants performed three repetitions of the Nordic exercise with a 1 min break between repetitions [

23], with the supervision of two physiotherapists. One physiotherapist performed the assessment using the My Jump Lab app, and the other helped the participant perform the exercise. After placing their knees on a mattress, participants were asked to lean their body forward, extending their knees, until they can no longer perform the exercise. A physiotherapist would stand behind and hold their feet. Additionally, participants were asked to perform the exercise with their hands crossed on their chest and, when it is not possible to continue extending their knees, they should remove their hands and place them next to their chest to support the fall [

22]. The moment the participants removed their hand from their chest was deemed the criteria for BPA estimation and eccentric peak torque assessment.

Before data collection, participants had the opportunity to become familiar with the exercise, by performing up to three repetitions.

This assessment was carried out in the laboratory of the physiotherapy clinic at the Egas Moniz School of Health and Science. All Nordic exercises were recorded by a tablet (Ipad mini-6, Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA), with the My Jump Lab app installed, positioned on the sagittal plane of the participants and mounted on a tripod, at a distance of 2.80 m and at 70 cm height. The data were recorded at a high frame rate (240 Hz). After each repetition, video analysis of the participants was performed, to ensure that they did not display excessive hip movement and managed to control the descent from the start of the exercise, since hip flexion during the Nordic exercise could influence knee joint torque [

47]. The values obtained by the app were the BPA and its respective hamstring peak torque, which were recorded for future comparison with the data collected by the isokinetic dynamometer. All data from the app was stored in the tablet, which was kept in the clinic and access to the data was exclusive to researchers involved in the study, solely for the duration of the present study. Regarding the procedure on the isokinetic dynamometer (Humac Norm, Stoughton, MA, USA), participants performed a warm-up which consisted of 20 repetitions of knee extensions and flexions, to understand how the dynamometer works submaximal repetitions and to become acquainted with the equipment and the movement. Afterwards, the participants performed the exercise five times with the dominant leg, with an angular velocity of 60°/s, for peak torque measurement, with 30 s of rest between each isometric contraction. The dominant leg was assessed by asking participants to step on a small bench and the limb first used was considered. The protocol used for the isokinetic dynamometer was similar to previous studies [

41]. Participants were seated with the hip joint at 90° (supine position = 0°), as recommended in previous studies [

11,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The dynamometer’s axis of rotation was aligned with the axis of rotation of the knee, between the lateral condyles of the femur and tibia. The clamp of the dynamometer’s lever arm was attached to the ankle, five centimeters from the malleolus, and the moment that the arm was adjusted to correct the gravity. Compensatory movements were limited by straps placed on the hip, shoulder, and tested thigh. Participants were instructed to hold onto the handles located under the seat. The range of movement was set as close to 90° as possible, with full knee extension being zero [

47].

The app measures torque bilaterally based on the body’s lever arm, while the isokinetic dynamometer assesses unilateral torque. This design was chosen to reflect common field practice but was acknowledged as a potential source of systematic bias.

4.7. Data Analysis

For the evaluation with the My Jump Lab, three repetitions were performed, while in the evaluation with the isokinetic dynamometer, five repetitions were performed. Data from the My Jump Lab app was analyzed by two independent evaluators, who selected manually (in the app) the BPA moment. This was determined by the frame where participants removed their hands from their chest, to stop the fall. With this angle calculated, the app estimated peak torque, considering the body measurements previously made for each participant. The mean torque value was considered for analysis. These two independent evaluators were blinded to the results from the isokinetic evaluation.

With regard to the isokinetic assessment, peak eccentric knee flexor torque for each of the five repetitions was established. The repetition eliciting the greatest peak torque was saved for further analysis.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

The mean and standard deviation were calculated to describe the characteristics of the collected data. The normality of the variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Concurrent validity was evaluated through the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), using a two-way random-effects model with a 95% confidence interval. The ICC values were interpreted as follows: values below 0.40 indicated poor reliability; values between 0.40 and 0.75 were considered to have moderate to good reliability; and values above 0.75 reflected excellent reliability. To assess the strength of association between methods, the Pearson correlation coefficient was also calculated and interpreted according to the following thresholds: values between 0.10 and 0.39 indicated a weak correlation; between 0.40 and 0.69 a moderate correlation; between 0.70 and 0.89 a strong correlation; and between 0.90 and 1.00 a very strong correlation [

52]. Reliability was evaluated using a two-way random-effects model with absolute agreement. The 95% confidence intervals for ICC were reported. Bland–Altman analysis was performed to assess systematic bias and limits of agreement between the My Jump Lab application and the isokinetic dynamometer, with the latter being considered as the gold standard. Additionally, the coefficient of variation (CV), expressed as a percentage, and the standard error of measurement (SEM) were calculated to provide further insights into the reliability of each method. A CV equal to or less than 15% was considered an indicator of good reliability [

52]. The significance level was set at

p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Jamovi statistical software (version 2.4).