Effects of Bodypump Training on Blood Pressure and Physical Fitness in Sedentary Older Adults with Hypertension: A Randomized Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

Covariate-Adjusted Analyses

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

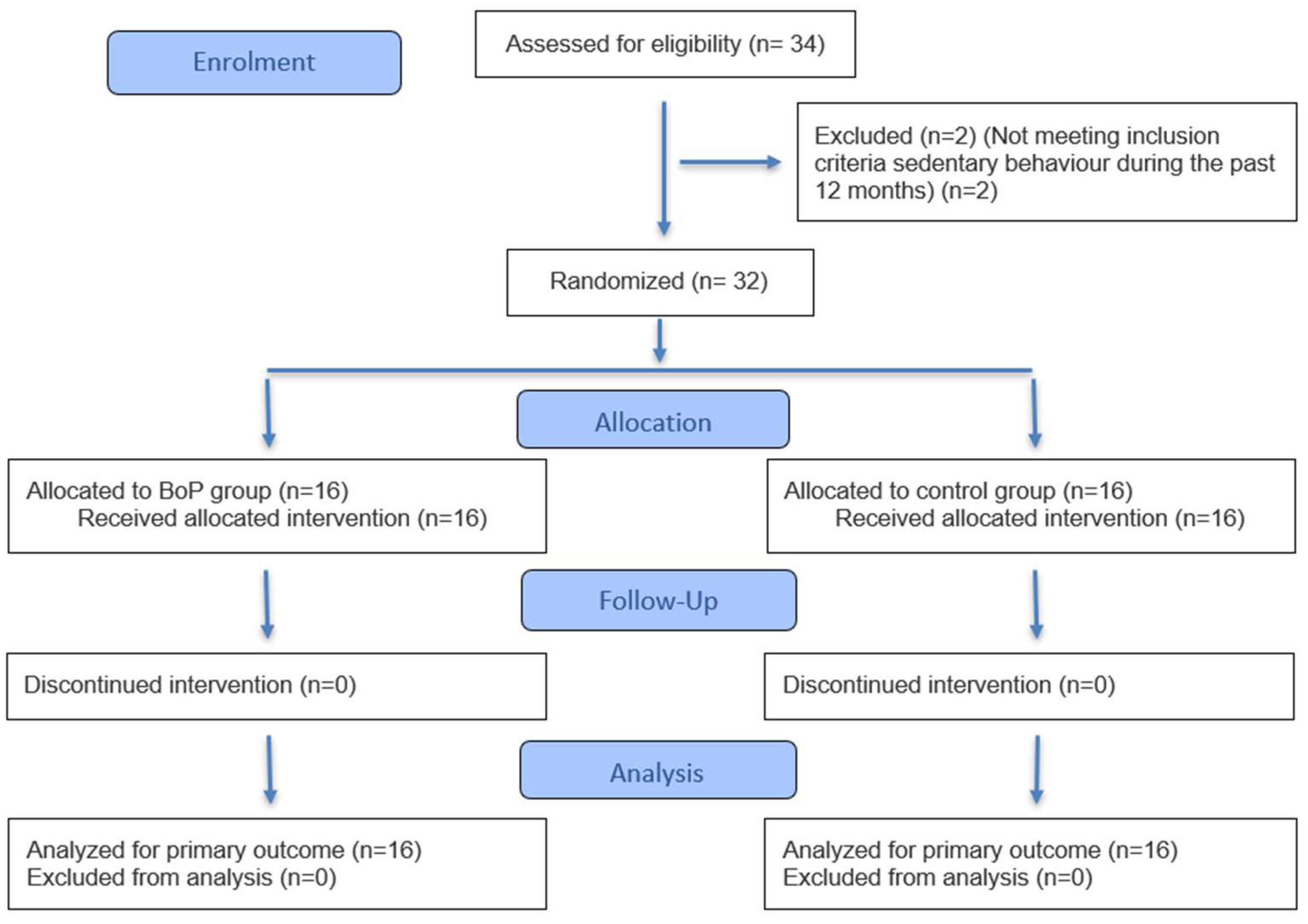

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Bodypump Training Program

4.4. Measurements

4.4.1. Resting Blood Pressure

4.4.2. Physical Fitness—Senior Fitness Test (SFT)

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Arm Curl |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| BoP | Bodypump |

| CG | Control Group |

| CS | Chair Stand |

| CS&R | Chair sit and reach |

| BS | Back Scratch |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| RPE | Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SFT | Senior Fitness Test |

| 2MS | 2-Minute Step |

| 8FUG | 8-Foot Up-and-Go |

References

- DeGuire, J.; Clarke, J.; Rouleau, K.; Roy, J.; Bushnik, T. Blood pressure and hypertension. Health Rep. 2019, 30, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Hypertension. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The SPRINT Research Group. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.M.; Musini, V.M. First-line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 8, CD001841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, B.M.Y.; Wong, Y.L.; Lau, C.P. Queen Mary Utilization of Antihypertensive Drugs Study: Side-effects of antihypertensive drugs. J. Clin. Pharm Ther. 2005, 30, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivasi, G.; Coscarelli, A.; Capacci, M.; Ceolin, L.; Turrin, G.; Tortù, V.; D’Andria, M.F.; Testa, G.D.; Ungar, A. Tolerability of Antihypertensive Medications: The Influence of Age. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2024, 31, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.R.; Mohile, S.G.; Juba, K.M.; Awad, H.; Wells, M.; Loh, K.P.; Flannery, M.; Culakova, E.; Tylock, R.; Ramsdale, E. Association of polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions with adverse treatment outcomes in older adults with advanced cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrod, P.J.J.; Doleman, B.; Blackwell, J.; O’Boyle, F.; Lund, J.N.; Phillips, B.E. Non-pharmacological strategies to reduce blood pressure in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2017, 390, S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carpio-Rivera, E.; Moncada-Jiménez, J.; Salazar-Rojas, W.; Solera-Herrera, A. Acute effects of exercise on blood pressure: A meta-analytic investigation. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2016, 106, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.J.; Deenmamode, A.H.P.; Griffiths, M.; Arnold, O.; Cooper, N.J.; Wiles, J.D.; O’Driscoll, J.M. Exercise training and resting blood pressure: A large-scale pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1317–1326. Available online: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/57/20/1317 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, G.M.d.V.d.; Frajácomo, F.T.T.; Haagsma, A.B.; Souza, D.L.B.; de Oliveira, V.B.; Olandoski, M.; Neto, J.R.F.; Jerez-Roig, J.; Baena, C.P. Physical activity and functional preservation in older adults with hip osteoarthritis: A comparative analysis of age cohorts in the SHARE study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acree, L.S.; Longfors, J.; Fjeldstad, A.S.; Fjeldstad, C.; Schank, B.; Nickel, K.J.; Montgomery, P.S.; Gardner, A.W. Physical activity is related to quality of life in older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkin, J.S.; Pinto, R.S.; Machado, C.L.F.; Wilhelm, E.N. Chronic effect of resistance training on blood pressure in older adults with prehypertension and hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 177, 112193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.A.; Huffman, K.M.; Wolever, R.Q.; Smith, P.J.; Siegler, I.C.; Ross, L.M.; Hauser, E.R.; Jiang, R.; Jakicic, J.M.; Costa, P.T.; et al. Determinants of Dropout from and Variation in Adherence to an Exercise Intervention: The STRRIDE Randomized Trials. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sports Med. 2022, 7, e000190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrance, C.; Tsofliou, F.; Clark, C. Adherence to community based group exercise interventions for older people: A mixed-methods systematic review. Prev. Med. 2016, 87, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Ruissen, G.R.; Dunlop, W.L.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Harden, S.M.; Wolf, S.A.; Liu, Y.; Schmader, T.; Puterman, E.; Sheel, A.W.; et al. Group-based physical activity for older adults (GOAL) randomized controlled trial: Exercise adherence outcomes. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Gottschall, J.S.; Benson, A.J.; Eys, M.; Hastings, B.; Evans, M.B. Perceptions of groupness during fitness classes positively predict recalled perceptions of exertion, enjoyment, and affective valence: An intensive longitudinal investigation. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2019, 8, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustaden, A.M.; Gjestvang, C.; Bø, K.; Haakstad, L.A.H.; Paulsen, G. Similar Energy Expenditure During BodyPump and Heavy Load Resistance Exercise in Overweight Women. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavarrías-Olmedo, M.; Franco-García, J.M.; García-Paniagua, R.; Calzada-Rodríguez, J.I.; Pérez-Gómez, J. Efectos agudos y crónicos de la práctica de Bodypump. J. Negat. No Posit. Results 2021, 6, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.; Kilding, A.; Sethi, S.; Merien, F.; Gottschall, J. A comparison of the acute physiological responses to BODYPUMPTM versus iso-caloric and iso-time steady state cycling. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Development and Validation of Criterion-Referenced Clinically Relevant Fitness Standards for Maintaining Physical Independence in Later Years. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, V.A.; Smart, N.A. Exercise training for blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e004473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.C.; Oliveira, A.S.; Pereira, M.P.; Figueira, T.R.; Ruas, V.D.; Goncxalves, M.; Denadai, B.S. Improvements in metabolic and neuromuscular fitness after 12-week bodypump® training. J. Strength Cond Res. 2011, 25, 3422–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrod, P.J.J.; Lund, J.N.; Phillips, B.E. Time-efficient physical activity interventions to reduce blood pressure in older adults: A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 389, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, J.W.D.; O’Driscoll, J.M.; Hulbert, S.; Scales, J.; Wiles, J.D. Convergent Validity of Ratings of Perceived Exertion During Resistance Exercise in Healthy Participants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, J.P.; Borg, G.A.V. Borg’s scales in strength training; from theory to practice in young and older adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.S.; Krinski, K.; Alves, R.C.; Benites, M.L.; Redkva, P.E.; Elsangedy, H.M.; Buzzachera, C.F.; Souza-Junior, T.P.; da Silva, S.G. The Use of Session RPE to Monitor the Intensity of Weight Training in Older Women: Acute Responses to Eccentric, Concentric, and Dynamic Exercises. J. Aging Res. 2014, 2014, 749317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmar, R.; Khabouth, J.; Topouchian, J.; El Feghali, R.; Mattar, J. Validation of three automatic devices for self-measurement of blood pressure according to the International Protocol: The Omron M3 Intellisense (HEM-7051-E), the Omron M2 Compact (HEM 7102-E), and the Omron R3-I Plus (HEM 6022-E). Blood Press. Monit. 2010, 15, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | BoP (n = 16) | CG (n = 16) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Δ% | d | p | Pre | Post | Δ% | d | p | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 155.9 ± 27.8 | 131.4 ± 18.0 a # | −15.7 | 2.7 | 0.001 | 153.1 ± 8.0 | 153.0 ± 11.1 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 0.164 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83.9 ± 12.1 | 76.8 ± 6.2 a # | −8.5 | 1.3 | 0.025 | 92.9 ± 10.3 | 92.3 ± 11.4 | −0.6 | −0.1 | 0.633 |

| CS (rep) | 15.3 ± 2.1 | 19.4 ± 2.8 a | 26.8 | −2.8 | <0.001 | 15.7 ± 3.2 | 16.1 ± 3.4 | 2.5 | −0.5 | 0.054 |

| AC (rep) | 19.4 ± 2.2 | 23.5 ± 2.2 a | 21.1 | −2.3 | <0.001 | 19.6 ± 3.8 | 20.3 ± 3.7 | 3.6 | −0.7 | 0.116 |

| 2MS (rep) | 90.9 ± 16.0 | 106.7 ± 13.2 a | 17.4 | −1.5 | <0.001 | 90.8 ± 13.6 | 91.7 ± 13.2 | 1 | −0.6 | 0.057 |

| 8FUG (sec) | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 7.3 ± 0.9 a | −7.6 | 3.6 | <0.001 | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 1.1 | −1.5 | 0.3 | 0.261 |

| CS&R (cm) | 24.3 ± 13.3 | 32.4 ± 12.0 | 33.3 | −1.6 | 0.057 | 27.8 ± 4.9 | 27.8 ± 5.2 | 0 | −0.1 | 0.751 |

| BS (cm) | 13.6 ± 8.2 | 18.5 ± 7.4 | 36 | −1.1 | 0.136 | 15.9 ± 5.2 | 16.5 ± 4.7 | 3.8 | −0.9 | 0.053 |

| Variable | BoP (95% CI) | CG (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Difference Between Groups (95% CI) | p | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 141.1–170.8 | 121.8–140.9 | 148.9–157.4 | 147.1–158.9 | 15.8 (12.7–18.8) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.4–90.3 | 73.5–80.1 | 87.4–98.4 | 86.3–98.4 | 8.1 (4.9–11.2) | <0.001 |

| CS (rep) | 14.2–16.3 | 17.9–20.8 | 14.0–17.4 | 14.2–17.9 | 3.8 (2.9–4.6) | <0.001 |

| AC (rep) | 18.2–20.5 | 22.3–24.7 | 17.6–21.7 | 18.4–22.3 | 3.4 (2.4–4.5) | <0.001 |

| 2MS (rep) | 82.4–99.4 | 99.7–114 | 83.5–98.0 | 84.6–98.7 | 14.9 (9.5–20.2) | <0.001 |

| 8FUG (sec) | 7.39–8.43 | 6.78–7.78 | 6.23–7.36 | 6.17–7.32 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | <0.001 |

| CS&R (cm) | 17.2–31.4 | 26.0–38.8 | 25.1–30.4 | 25.1–30.6 | 8.0 (5.6–10.4) | <0.001 |

| BS (cm) | 9.19–17.9 | 14.6–22.4 | 13.1–18.6 | 14.0–19.0 | 4.3 (1.9–6.7) | <0.001 |

| Variable | BoP adj Mean (95% CI) | CG adj Mean (95% CI) | η2p | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | 131 (128–133) | 147 (145–149) | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.8 (78.9–84.6) | 90.2 (88.1–92.3) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| CS (rep) | 19.6 (18.6–20.5) | 15.9 (15.2–16.5) | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| AC (rep) | 23.7 (22.6–24.9) | 20.3 (19.5–21.1) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| 2MS (rep) | 107.4 (102.2–112.6) | 92.1 (88.3–96.0) | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| 8FUG (sec) | 6.62 (6.49–6.75) | 7.25 (7.15–7.35) | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| CS&R (cm) | 34.4 (32.0–36.8) | 26.3 (24.5–28.1) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| BS (cm) | 19.3 (16.9–21.6) | 15.8 (14.1–17.5) | 0.2 | 0.010 |

| Variable | BoP adj Mean (95% CI) | CG adj Mean (95% CI) | η2p | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | 131 (128–133) | 147 (144–149) | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.9 (77.9–82.0) | 88.5 (86.0–90.9) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| CS (rep) | 19.3 (18.6–20.0) | 15.6 (14.9–16.4) | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| AC (rep) | 23.4 (22.6–24.3) | 20.0 (19.0–21.0) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| 2MS (rep) | 106.3 (102.5–110.1) | 91.0 (86.4–95.6) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| 8FUG (sec) | 6.86 (6.77–6.96) | 7.50 (7.38–7.62) | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| CS&R (cm) | 33.9 (32.1–35.6) | 25.7 (23.5–27.8) | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| BS (cm) | 19.3 (17.6–21.0) | 16.0 (13.9–18.0) | 0.2 | 0.021 |

| Variable | BoP (n = 16) | CG (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.3 ± 5.0 | 65.6 ± 7.7 |

| BMI | 30.6 ± 4.3 | 32.1 ± 5.2 |

| Medication n (%) | 0 | 5 (31.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez Chavarría, M.J.; Chavarrías-Olmedo, M.; Pérez-Gómez, J. Effects of Bodypump Training on Blood Pressure and Physical Fitness in Sedentary Older Adults with Hypertension: A Randomized Trial. Physiologia 2025, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040052

Rodríguez Chavarría MJ, Chavarrías-Olmedo M, Pérez-Gómez J. Effects of Bodypump Training on Blood Pressure and Physical Fitness in Sedentary Older Adults with Hypertension: A Randomized Trial. Physiologia. 2025; 5(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez Chavarría, Manuel Jesús, Manuel Chavarrías-Olmedo, and Jorge Pérez-Gómez. 2025. "Effects of Bodypump Training on Blood Pressure and Physical Fitness in Sedentary Older Adults with Hypertension: A Randomized Trial" Physiologia 5, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040052

APA StyleRodríguez Chavarría, M. J., Chavarrías-Olmedo, M., & Pérez-Gómez, J. (2025). Effects of Bodypump Training on Blood Pressure and Physical Fitness in Sedentary Older Adults with Hypertension: A Randomized Trial. Physiologia, 5(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia5040052