A Reliable Semi-Continuous Cultivation Mode for Stable High-Quality Biomass Production of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgal Strain and Maintenance Conditions

2.2. Algal Pre-Culture for PBR Inoculation

2.3. Flat-Panel PBRs

2.4. Gas-Air Mixture Supply

2.5. Temperature Control System

2.6. Growth Characteristics

- The productivity (P) was estimated by dry weight (g DW L−1 d−1):

- The specific growth rate (μ) was estimated by the change in the culture OD (d−1):

- The biomass productivity for each drainage period was calculated as the difference between the final and initial biomass concentrations, divided by the duration of the period. The specific growth rate was determined for each period using the same approach.

2.7. pH Measurements

2.8. Carbon Dioxide Utilization Efficiency

2.9. Biochemical Composition

- [Chl a]—chlorophyll a content,

- [Chl b]—chlorophyll b content,

- [Car]—total carotenoid content.

2.10. Photosynthetic Activity

2.11. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Cultivation in Batch Mode

3.2. Cultivation in Semi-Continuous Mode

3.3. Biochemical Composition and Photosynthetic Activity

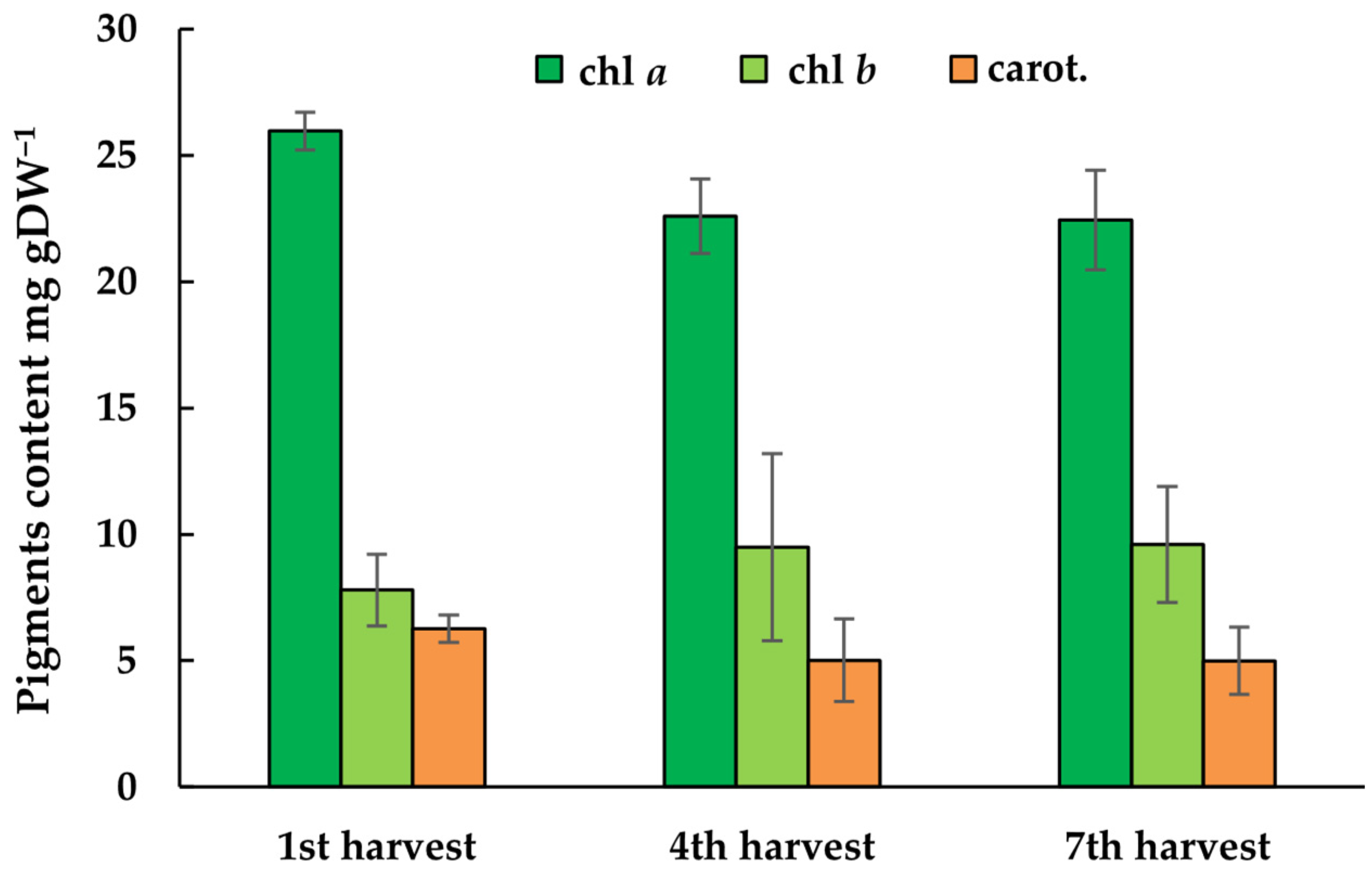

3.3.1. Pigment Content and Photosynthetic Activity

3.3.2. Protein, Total Lipid and Carbohydrate Composition of the Biomass

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultivation in Batch Mode

4.2. Cultivation in Semi-Continuous Mode

4.3. Stability of Biomass Composition and Photosyntetic Activity

4.4. Prospects of Chlorella Strains Semi-Continuous Cultivation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| µ | specific growth rate |

| CUE | cardon dioxide utilization efficiency |

| Iave | average irradiance or average illumination level |

| g DW | gram of dry weight |

| GAM | gas-air mixture |

| HRT | hydraulic retention time |

| IPP RAS | Institute of Plants Physiology of Russian Academy of Sciences |

| LED | light emitting diode |

| ρ | dry biomass concentration |

| ρ0 | starting dry biomass concentration |

| ρfin | final dry biomass concentration |

| MCO2 | mass of total supplied CO2 |

| M0 | starting weigh of dry biomass in PBR after inoculation |

| MPBR | weight of dry biomass in the working volume of PBR at the moment |

| PBR | photobioreactor |

| PBR FP | flat-panel photobioreactor |

| Psp | specific productivity |

| RGAM | GAM aeration rate |

| Tdbl | biomass doubling time |

| VPBR | working volume of PBR |

| vvm | volume of sparged gas per unit volume of growth medium per minute |

References

- Diaz, C.J.; Douglas, K.J.; Kang, K.; Kolarik, A.L.; Malinovski, R.; Torres-Tiji, Y.; Molino, J.V.; Badary, A.; Mayfield, S.P. Developing algae as a sustainable food source. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1029841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, W.S.; Kee, P.E.; Lan, J.C.-W.; Chen, W.-H.; Chang, J.-S.; Khoo, K.S. Unveiling the rise of microalgae-based foods in the global market: Perspective views and way forward. Food Biosci. 2025, 66, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourelle, M.L.; Díaz-Seoane, F.; Inoubli, S.; Gómez, C.P.; Legido, J.L. Microalgae and Cyanobacteria Exopolysaccharides: An Untapped Raw Material for Cosmetic Use. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwil, M.; Mihelic, R.; Matraszek-Gawron, R.; Terlecka, P.; Skoczylas, M.M.; Terlecki, K. Comprehensive Review of the Latest Investigations of the Health-Enhancing Effects of Selected Properties of Arthrospira and Spirulina Microalgae on Skin. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchkova, T.V.; Khapchaeva, S.A.; Zotov, V.S.; Lukyanov, A.A.; Solovchenko, A.E. Marine and freshwater microalgae as a sustainable source of cosmeceuticals. Mar. Biol. J. 2021, 6, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjakovic, M.; Sinaga, N. The Perspective of Large-Scale Production of Algae Biodiesel. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, A.; Dauvillée, D.; Lancelon-Pin, C.; Dimitriades-Lemaire, A.; Compadre, A.; Dubreuil, C.; Alvarez, P.; Sassi, J.-F.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Putaux, J.-L.; et al. From raw microalgae to bioplastics: Conversion of Chlorella vulgaris starch granules into thermoplastic starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 342, 122342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilling, K. (Ed.) Biofuels from Algae: Methods and Protocols; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Politaeva, N.; Smyatskaya, Y.; Al Afif, R.; Pfeifer, C.; Mukhametova, L. Development of Full-Cycle Utilization of Chlorella sorokiniana Microalgae Biomass for Environmental and Food Purposes. Energies 2020, 13, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.W.R.; Tan, X.; Khoo, K.S.; Ng, H.S.; Jonglertjunya, W.; Yew, G.Y.; Show, P.L. Microalgae-based bioplastics: Future solution towards mitigation of plastic wastes. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 112620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.K.; Lee, J. Achievements in the production of bioplastics from microalgae. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 1147–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chang, J.-S.; Ng, I.-S. Towards protein production and application by using Chlorella species as circular economy. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Wenqiang Qi, W.; Cheng, D.; Tang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Enhancing Carbohydrate Productivity of Chlorella sp. AE10 in Semi-continuous Cultivation and Unraveling the Mechanism by Flow Cytometry. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 185, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobus, N.V.; Knyazeva, M.A.; Popova, A.F.; Kulikovskiy, M.S. Carbon Footprint Reduction and Climate Change Mitigation: A Review of the Approaches, Technologies, and Implementation Challenges. C 2023, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, J.; Silva, T.P.; Paixão, S.M.; Alves, L. Development of a bench-scale photobioreactor with a novel recirculation system for continuous cultivation of microalgae. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, G.; Dubey, B.K.; Sen, R. A comparative life cycle assessment of microalgae production by CO2 sequestration from flue gas in outdoor raceway ponds under batch and semi-continuous regime. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Salinas, C.E.; Patlán-Juárez, G.; Okoye, P.U.; Guillén-Garcés, A.; Sebastian, P.J.; Arias, D.M. Long-term semi-continuous production of carbohydrate-enriched microalgae biomass cultivated in low-loaded domestic wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.B.; Lam, M.K.; Uemura, Y.; Lim, J.W.; Wong, C.Y.; Ramli, A.; Kiew, P.L.; Lee, K.T. Semi-continuous cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris using chicken compost as nutrients source: Growth optimization study and fatty acid composition analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 164, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Linares, L.C.; Gutiérrez-Márquez, A.; Guerrero-Barajas, C. Semi-continuous culture of a microalgal consortium in open ponds under greenhouse conditions using piggery wastewater effluent. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 12, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Gangwar, A.; Kumar, S. Semi-continuous cultivation of microalgae to treat coal mine effluent in pilot scale: Nutrient removal, biodesalination and fatty acid composition analysis. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 67, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetani, I.; Sposób, M.; Tiron, O. Semi-continuous cultivation for enhanced protein production using indigenous green microalgae and synthetic municipal wastewater. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ramaswamy, S. Dynamic process model and economic analysis of microalgae cultivation in flat panel photobioreactors. Algal Res. 2019, 39, 101445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Nielsen, S.L.; Eroldogan, O.T.; Haznedaroglu, B.Z.; Rinkevich, B.; Fazi, S.; Robbens, J.; Vasquez, M.; Einarsson, H. Overview and Challenges of Large-Scale Cultivation of Photosynthetic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz, D.; McGowen, J.A.; Quinn, J.C. Techno-economic analysis of microalgae cultivation strategies: Batch and semi-continuous approaches. Algal Res. 2025, 90, 104109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Kujawska, N.; Talbierz, S. Microalgae Cultivation Technologies as an Opportunity for Bioenergetic System Development—Advantages and Limitations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dailami, A.; Koji, I.; Ahmad, I.; Goto, M. Potential of Photobioreactors (PBRs) in Cultivation of Microalgae. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 27, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, X.; Chang, H.; Ou, S.; Wang, H. Role of Bioreactors in Microbial Biomass and Energy Conversion. In Bioreactors for Microbial Biomass and Energy Conversion; Liao, Q., Chang, J.S., Herrmann, C., Xia, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 39–78. [Google Scholar]

- Onen Cinar, S.; Chong, Z.K.; Kucuker, M.A.; Wieczorek, N.; Cengiz, U.; Kuchta, K. Bioplastic Production from Microalgae: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, R.; Pandey, F.K.; Ranganathan, P.; Singh, S.; Udayan, F.; Awasthi, M.K.; Hoang, A.T.; Chilakamarry, C.R.; Kim, S.H.; Sim, S.J. Design and applications of photobioreactors—A review. Biores. Technol. 2022, 349, 126858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirk, W.A.; Bálint, P.; Široká, J.; Novák, O.; Rétfalvi, T.; Berzsenyi, Z.; Notterpek, J.; Varga, Z.; Maróti, G.; Van Staden, J.; et al. Comparison of plant biostimulating properties of Chlorella sorokiniana biomass produced in batch and semi-continuous systems supplemented with pig manure or acetate. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 381, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Xu, X.; Dai, B. Optimization of semi-continuous cultivation conditions for the improvement of lipid productivity from thermo-tolerant Chlorella vulgaris XJW. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2021, 47, 6714–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Padhi, D.; Mandal, S.; Kumar, V.; Nayak, M. Performance evaluation of Chlorella sp. BRE5 for augmented biomass and lipid production implementing semi-continuous cultivation strategy. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025, 15, 12301–12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Kong, F.; Liu, B.-F.; Song, Q.; Ren, N.-Q.; Ren, H.-Y. Enhancement of microalgae lipid production under multiple stressors and tetracycline and heavy metal removal in semi-continuous operation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 162002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.; Bulynina, S.; Ziganshin, A. Semi-continuous cultivation of indigenous Chlorella sorokiniana for biomass and pigment production. In XI International Scientific and Practical Conference Innovative Technologies in Environmental Science and Education (ITSE-2023), Divnomorskoe Village, Russia; Rudoy, D.V., Olshevskaya, A.V., Odabashyan, M.Y., Eds.; E3S Web of Conferences: Les Ulis, France, 2023; Volume 431, p. 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Nayak, M. Enhancing biomass and lipid productivity of Chlorella sp. BRE5 with surplus phosphorus supply implementing semi-continuous cultivation in the indoor and outdoor reactor system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 23414–23429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinetova, M.A.; Sidorov, R.A.; Starikov, A.Y.u.; Voronkov, A.S.; Medvedeva, A.S.; Krivova, Z.V.; Pakholkova, M.S.; Bachin, D.V.; Bedbenov, V.S.; Gabrielyan, D.A.; et al. Assessment of the biotechnological potential of cyanobacterial and microalgal strains from IPPAS culture collection. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2020, 56, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielyan, D.A.; Sinetova, M.A.; Gabrielyan, A.K.; Bobrovnikova, L.A.; Bedbenov, V.S.; Starikov, A.Y.; Zorina, A.A.; Gabel, B.V.; Los, D.A. Laboratory System for Intensive Cultivation of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielyan, D.A.; Sinetova, M.A.; Gabel, B.V.; Gabrielian, A.K.; Markelova, A.G.; Rodionova, M.V.; Bedbenov, V.S.; Shcherbakova, N.V.; Los, D.A. Cultivation of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1 in Flat-Panel Photobioreactors: From a Laboratory to a Pilot Scale. Life 2022, 12, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielyan, D.A.; Gabel, B.V.; Sinetova, M.A.; Gabrielian, A.K.; Markelova, A.G.; Shcherbakova, N.V.; Los, D.A. Optimization of CO2 Supply for the Intensive Cultivation of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1 in the Laboratory and Pilot-Scale Flat-Panel Photobioreactors. Life 2022, 12, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivina, E.S.; Bobrovnikova, L.A.; Temraleeva, A.D.; Markelova, A.G.; Gabrielyan, D.A.; Sinetova, M.A. Description of Neochlorella semenenkoi gen. et. sp. nov. (Chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae), a Novel Chlorella-like Alga with High Biotechnological Potential. Diversity 2023, 15, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoglin, L.N.; Gabel, B.V. Potential productivity of microalgae in industrial photobioreactors. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 47, 668–673. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielyan, D.A.; Sinetova, M.A.; Savinykh, G.A.; Zadneprovskaya, E.V.; Goncharova, M.A.; Markelova, A.G.; Gabrielian, A.K.; Gabel, B.V.; Lobus, N.V. Productivity and Carbon Utilization of Three Green Microalgae Strains with High Biotechnological Potential Cultivated in Flat-Panel Photobioreactors. Phycology 2025, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, E.; Morimura, Y.; Tamiya, H. Some data on the growth physiology of Chlorella studied by the technique of synchronous culture. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1957, 69, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.A.; Curtis, B.S.; Curtis, W.R. Improving accuracy of cell and chromophore concentration measurements using optical density. BMC Biophys. 2013, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, W.L. Determination of the dry weight of herbage by drying methods. Grass Forage Sci. 1960, 15, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.M.M.N.; Sueitt, A.P.E.; Daniel, L.A. Using correlation of variables to compare different configurations of microalgae-based wastewater treatment systems. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 4957–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, C.G.; Lam, M.K.; Lee, K.T. Pilot-scale semi-continuous cultivation of microalgae Chlorella vulgaris in bubble column photobioreactor (BC-PBR): Hydrodynamics and gas–liquid mass transfer study. Algal Res. 2016, 15, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.J.; Garcin, C.; van Hille, R.P.; Harrison, S.T.L. Interference by pigment in the estimation of microalgal biomass concentration by optical density. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 85, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Su, Y. Process effect of microalgal-carbon dioxide fixation and biomass production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivina, E.; Sinetova, M.; Zadneprovskaya, E.; Ivanova, M.; Starikov, A.; Shibzukhova, K.; Lobakova, E.; Bukin, Y.; Portnov, A.; Temraleeva, A. The genus Coelastrella (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta): Molecular species delimitation, biotechnological potential, and description of a new species Coelastrella affinis sp. nov., based on an integrative taxonomic approach. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2024, 117, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, R.J. Consistent sets of spectrophotometric chlorophyll equations for acetone, methanol and ethanol solvents. Photosynth. Res. 2006, 89, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.C. Batch Cultivation of Microalgae in the Labfors 5 Lux Photobioreactor with LED Flat Panel Option. InforsHT Application Note. 2014; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/101601314/Batch_cultivation_of_microalgae_in_the_Labfors_5_Lux_Photobioreactor_with_LED_Flat_Panel_Option (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Soto-Ramírez, R.; Tavernini, L.; Zúñiga, H.; Poirrier, P.; Chamy, R. Study of microalgal behaviour in continuous culture using photosynthetic rate curves: The case of chlorophyll and carotenoid production by Chlorella vulgaris. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 3639–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.-Q.; Tan, X.-B.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Yang, L.-B.; Zhao, F.-C.; Guo, J. Continuous cultivation of Chlorella pyrenoidosa using anaerobic digested starch processing wastewater in the outdoors. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 185, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavřel, T.; Schoffman, H.; Lukeš, M.; Fedorko, J.; Keren, N.; Červený, J. Monitoring fitness and productivity in cyanobacteria batch cultures. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guschina, I.A.; Harwood, J.L. Lipids and lipid metabolism in eukaryotic algae. Prog. Lipid. Res. 2006, 45, 160–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenenko, V.E.; Vladimirova, M.G.; Orleanskaja, O.B.; Raikov, N.I.; Kovanova, E.S. Physiological characteristics of Chlorella sp. K under conditions of high extreme temperatures. II. Changes in biosyntheses, ultrastructure and activity photosynthetical apparatus during uncoupling of cellular functions by extreme temperature. Physiol. Plants (Fiziol. Rast.) 1969, 16, 210–220. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Chinjoo, N.; Golzary, A. Microalgae: Revolutionizing skin repair and enhancement. Biotechnol. Rep. 2025, 47, e00911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dilution Fraction, % | 0 | 50 | 75 | 87.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest volume in one reactor, L | 0 | 2.5 | 3.75 | 4.375 |

| Final Batch Biomass (day 3), g DW L−1 | 4.70 ± 0.25 | 4.66 ± 0.11 | 4.08 ± 0.13 | 4.53 ± 0.22 |

| Harvest period, days | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Biomass concentration of harvested suspension *, g DW L−1 | 7.21 ± 0.40 | 4.38 ± 0.06 | 3.74 ± 0.08 | 2.73 ± 0.17 |

| pH level range in harvest period | 6.28 ± 0.01–8.33 ± 0.03 | 7.82 ± 0.1– 8.25 ± 0.08 | 7.28 ± 0.09– 8.32 ± 0.06 | 6.72 ± 0.05– 8.16 ± 0.06 |

| Average biomass gained in harvest period, g DW | 36.07 ± 1.99 ** | 10.96 ± 0.16 | 14.03 ± 0.32 | 11.94 ± 0.86 |

| Productivity in harvest period *, g DW L−1 d−1 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 1.36 ± 0.04 | 1.11 ± 0.09 |

| Cultivation time, days | 16 (8 × 2) | 17 | 17 | 15 |

| Total harvested volume, L | 10 | 22.5 | 31.25 | 31.25 |

| Total biomass yield, g DW | 72.14 ± 1.99 | 96.56 ± 2.56 | 114.37 ± 3.28 | 83.81 ± 6.23 |

| FA, % | 1st Harvest | 4th Harvest | 7th Harvest |

|---|---|---|---|

| C14:0 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.03 |

| C16:0 | 25.9 ± 0.94 | 26.1 ± 0.66 | 25.8 ± 0.31 |

| C16:1Δ7 | 2.3 ± 0.46 | 2.5 ± 0.43 | 2.0 ± 0.26 |

| C16:1Δ9 | 0.6 ± 0.07 | 0.6 ± 0.09 | 0.6 ± 0.04 |

| C16:2Δ7,10 | 14.2 ± 1.64 | 13.9 ± 1.39 | 15.1 ± 1.03 |

| C16:3Δ7,10,13 | 5.1 ± 0.02 | 6.5 ± 0.44 | 5.3 ± 0.41 |

| C18:0 | 1.1 ± 0.25 | 1.5 ± 0.03 | 1.5 ± 0.09 |

| C18:1Δ9 | 3.9 ± 1.13 | 4.3 ± 1.31 | 3.1 ± 0.79 |

| C18:1Δ11 | 1.1 ± 0.06 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.08 |

| C18:2Δ9,12 | 32.8 ± 1.52 | 29.3 ± 1.81 | 33.1 ± 1.30 |

| C18:3Δ9,12,15 | 12.7 ± 0.45 | 14.1 ± 1.02 | 12.4 ± 1.21 |

| UI | 1.552 ± 0.035 | 1.564 ± 0.027 | 1.561 ± 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gabrielyan, D.A.; Sinetova, M.A.; Gabel, B.V.; Gabrielian, A.K.; Starikov, A.Y.; Voloshin, R.A.; Markelova, A.; Savinykh, G.A.; Shcherbakova, N.V.; Los, D.A. A Reliable Semi-Continuous Cultivation Mode for Stable High-Quality Biomass Production of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1. Phycology 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010004

Gabrielyan DA, Sinetova MA, Gabel BV, Gabrielian AK, Starikov AY, Voloshin RA, Markelova A, Savinykh GA, Shcherbakova NV, Los DA. A Reliable Semi-Continuous Cultivation Mode for Stable High-Quality Biomass Production of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1. Phycology. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabrielyan, David A., Maria A. Sinetova, Boris V. Gabel, Alexander K. Gabrielian, Alexander Y. Starikov, Roman A. Voloshin, Alexandra Markelova, Grigoriy A. Savinykh, Natalia V. Shcherbakova, and Dmitry A. Los. 2026. "A Reliable Semi-Continuous Cultivation Mode for Stable High-Quality Biomass Production of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1" Phycology 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010004

APA StyleGabrielyan, D. A., Sinetova, M. A., Gabel, B. V., Gabrielian, A. K., Starikov, A. Y., Voloshin, R. A., Markelova, A., Savinykh, G. A., Shcherbakova, N. V., & Los, D. A. (2026). A Reliable Semi-Continuous Cultivation Mode for Stable High-Quality Biomass Production of Chlorella sorokiniana IPPAS C-1. Phycology, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010004