Environmental Degradation in the Italian Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons Shown by Satellite Imagery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

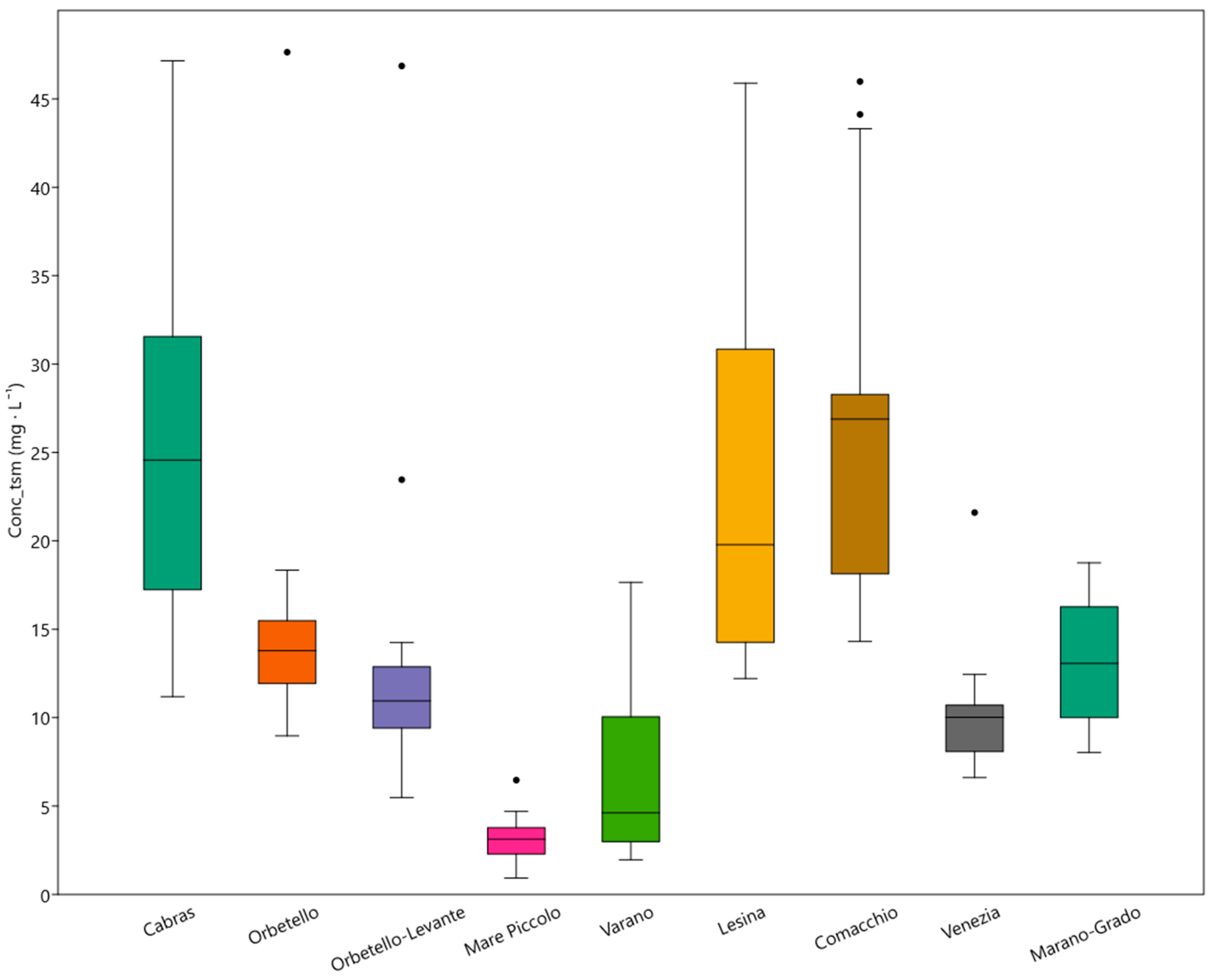

3.1. General Characteristics of Optical Parameters During the Study Period

3.2. Temporary Trends in Water Quality by Lagoon

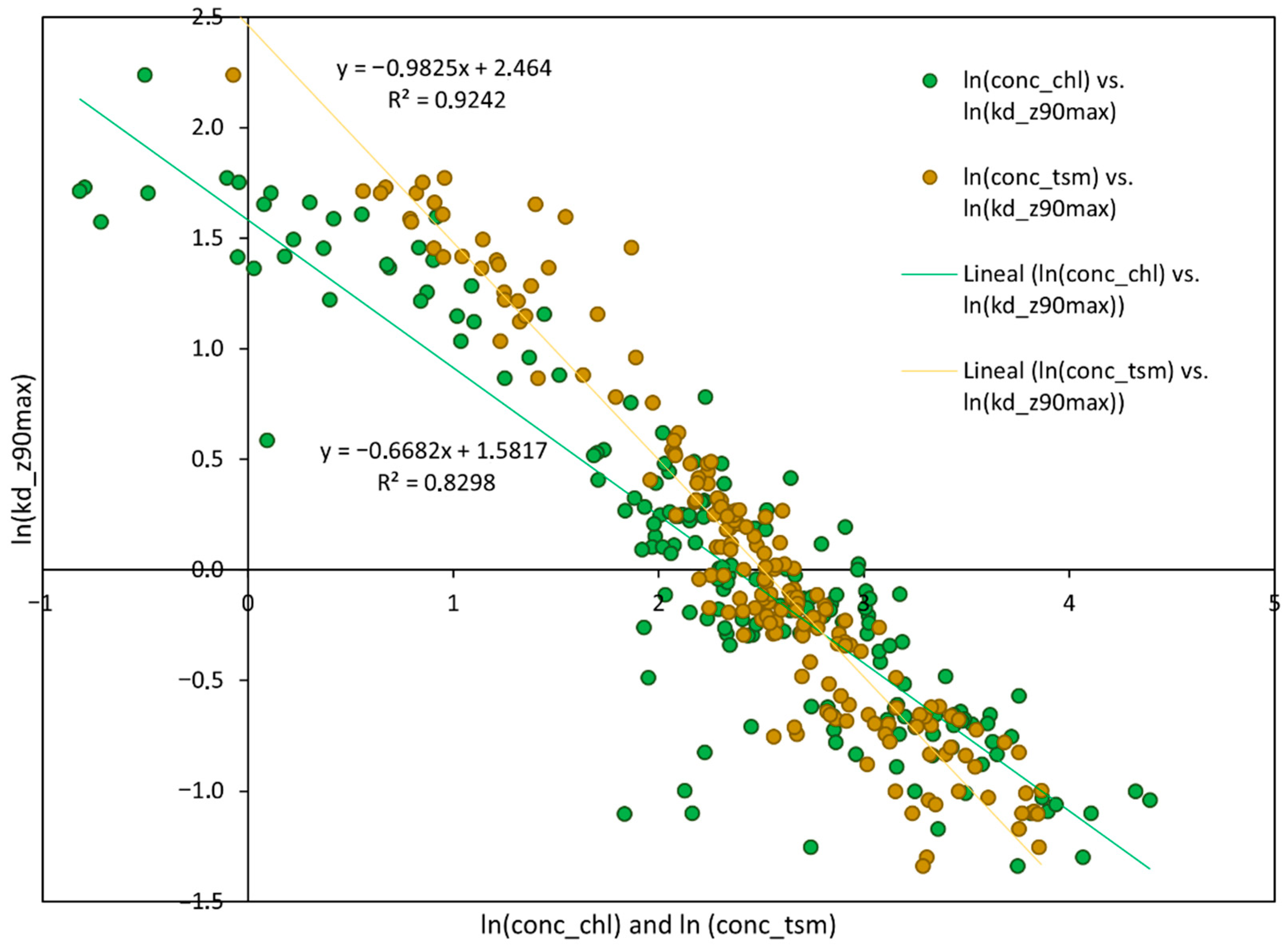

3.3. Relationship Between Transparency and Water Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TSM | Total suspended matter concentration |

| Kd_z90max | Water transparency |

| Chl-a | Chlorophyll-a concentration |

References

- Soria, J.; Pérez, R.; Sòria-Pepinyà, X. Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons Review: Sites to Visit before Disappearance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Rieradevall, M.; Farrés-Corell, R.; Newton, A. Annual characterisation of four Mediterranean coastal lagoons subjected to intense human activity. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 114, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjerfve, B. Coastal Lagoons. In Coastal Lagoons Processes; Kjerfve, B., Ed.; Elsevier Oceanography Series; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 60, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.-L. Improved modelling of the Messinian Salinity Crisis and conceptual implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2006, 238, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, R. Biodiversity of coastal lagoon ecosystems and their vulnerability to global change. In Ecosystems Biodiversity; Grillo, O., Venore, G., Eds.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. 1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A31992L0043 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rodrigues-Filho, J.L.; Macêdo, R.L.; Sarmento, H.; Pimenta, V.R.A.; Alonso, C.; Teixeira, C.R.; Pagliosa, P.R.; Netto, S.A.; Santos, N.C.L.; Daura-Jorge, F.G.; et al. From ecological functions to ecosystem services: Linking coastal lagoons biodiversity with human well-being. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2611–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, A.; Brito, A.C.; Icely, J.D.; Derolez, V.; Clara, I.; Angus, S.; Schernewski, G.; Inácio, M.; Lillebø, A.I.; Sousa, A.I.; et al. Assessing, quantifying and valuing the ecosystem services of coastal lagoons. J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 44, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataudella, S.; Crosetti, D.; Massa, F. Mediterranean coastal lagoons: Sustainable management and interactions among aquaculture, capture fisheries and the environment. Gen. Fish. Comm. Mediterr. Stud. Rev. 2015, 95, 293. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2b9abb35-bb50-4c9d-bd7c-cbc98d21600c/content (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Lewis, D.M.; Cook, G.S. Freshwater discharge disrupts linkages between the environment and estuarine fish community. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo Brusà, R.; Feola, A.; Cacciatore, F.; Ponis, E.; Sfriso, A.; Franzoi, P.; Lizier, M.; Peretti, P.; Matticchio, B.; Baccetti, N.; et al. Conservation actions for restoring the coastal lagoon habitats: Strategy and multidisciplinary approach of LIFE Lagoon Refresh. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 979415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Campillo, S.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; García-Lacunza, A.; García-Oliva, M.; Ibañez, H.; Navarro-Martínez, P.C.; Pérez-Marcos, M.; Pérez-Ruzafa, I.M.; Quispe-Becerra, J.I.; et al. Long-Term Dynamic in Nutrients, Chlorophyll a, and Water Quality Parameters in a Coastal Lagoon During a Process of Eutrophication for Decades, a Sudden Break and a Relatively Rapid Recovery. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmit, X.; Thieu, V.; Billen, G.; Campuzano, F.; Dulière, V.; Garnier, J.; Lassaletta, L.; Ménesguen, A.; Neves, R.; Pinto, L.; et al. Reducing marine eutrophication may require a paradigmatic change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 1444–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nienhuis, P.H. Eutrophication, Water Management, and the Functioning of Dutch Estuaries and Coastal Lagoons. Estuaries 1992, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Losada, I.J.; Hendriks, I.E.; Mazarrasa, I.; Marbà, N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrackin, M.L.; Jones, H.P.; Jones, P.C.; Moreno-Mateos, D. Recovery of lakes and coastal marine ecosystems from eutrophication: A global meta-analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017, 62, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, G.M.; Zaggia, L.; Manfè, G.; Lorenzetti, G.; Parnell, K.; Soomere, T.; Rapaglia, J.; Molinaroli, E. The effects of ship wakes in the Venice Lagoon and implications for the sustainability of shipping in coastal waters. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorini, V.; Malet, N.; Garrido, M.; Four, B.; Etourneau, S.; Leoncini, A.S.; Dufresne, C.; Cecchi, P.; Pasqualini, V. Long-term ecological trajectories of a disturbed Mediterranean coastal lagoon (Biguglia lagoon): Ecosystem-based approach and considering its resilience for conservation? Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 937795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Hennig, K.; Kala, J.; Andrys, J.; Hipsey, M.R. Climate change overtakes coastal engineering as the dominant driver of hydrological change in a large shallow lagoon. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 5673–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, S.; Ren, P. Underwater color disparities: Cues for enhancing underwater images toward natural color consistencies. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Q. WaterCycleDiffusion: Visual–Textual Fusion Empowered Underwater Image Enhancement. Inf. Fusion 2026, 127, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquavita, A.; Aleffi, I.F.; Benci, C.; Bettoso, N.; Crevatin, E.; Milani, L.; Tamberlich, F.; Toniatti, L.; Barbieri, P.; Licen, S.; et al. Annual characterization of the nutrients and trophic state in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon: The Marano and Grado Lagoon (northern Adriatic Sea). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2015, 2, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facca, C.; Ceoldo, S.; Pellegrino, N.; Sfriso, A. Natural recovery and planned intervention in coastal wetlands: Venice Lagoon (Northern Adriatic Sea, Italy) as a case study. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 968618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Venice and Its Lagoon. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/394/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Patonai, K.; Lanzoni, M.; Castaldelli, G.; Jordán, F.; Gavioli, A. Eutrophication triggered changes in network structure and fluxes of the Comacchio Lagoon (Italy). PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, L.; Fabbrocini, A.; Manzo, C.; D’Adamo, R. Hydrological heterogeneity, nutrient dynamics and water quality of a non-tidal lentic ecosystem (Lesina Lagoon, Italy). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2009, 84, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchiulli, A.; Focardi, S.; Renzi, M.; Scirocco, T.; Cilenti, L.; Breber, P.; Bastianoni, S. Environmental heterogeneity patterns and assessment of trophic levels in two Mediterranean lagoons: Orbetello and Varano, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 402, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, M.; De Vittor, C.; Comici, C.; Relitti, F.; Auriemma, R.; Alabiso, G.; Del Negro, P. Recent evolution of the physical–chemical characteristics of a Site of National Interest—The Mar Piccolo of Taranto (Ionian Sea)—And changes over the last 20 years. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 12675–12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, E.; Bergamin, L.; Croudace, I.W.; Ausili, A.; Maggi, C.; Gabellini, M. Establishing geochemical background levels of selected trace elements in areas having geochemical anomalies: The case study of the Orbetello lagoon (Tuscany, Italy). Environ. Pollut. 2015, 202, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, P.; De Falco, G.; Como, S.; Casu, D.; Floris, A.; Petrov, A.N.; Castelli, A.; Perilli, A. Distribution and ecological relevance of fine sediments in organic-enriched lagoons: The case study of the Cabras lagoon (Sardinia, Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 56, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.E. A trophic state index for lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Observer, Volume 1982, Issue 1; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulina, S.; Padedda, B.M.; Satta, C.T.; Sechi, N.; Lugliè, A. Long-term phytoplankton dynamics in a Mediterranean eutrophic lagoon (Cabras Lagoon, Italy). Plant Biosyst. 2012, 146, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padedda, B.M.; Pulina, S.; Magni, P.; Sechi, N.; Lugliè, A. Phytoplankton dynamics in relation to environmental changes in a phytoplankton-dominated Mediterranean lagoon (Cabras Lagoon, Italy). Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 2012, 3, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaroli, P.; Bartoli, M.; Giordani, G.; Naldi, M.; Orfanidis, S.; Zaldivar, J.M. Community shifts, alternative stable states, biogeochemical controls and feedbacks in eutrophic coastal lagoons: A brief overview. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2008, 18, S105–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, Y.I.; Dallocchio, F.; Gelli, F.; Pregnolato, L. Phosphorus metabolism in anthropogenically transformed lagoon ecosystems: The Comacchio lagoons (Ferrara, Italy). J. Sea Res. 1996, 35, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroppo, C.; Roselli, L.; Di Leo, A. Hydrological conditions and phytoplankton community in the Lesina lagoon (southern Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1784–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangio, D.; Manella, N.; Ungaro, N. Environmental quality characteristics of the Apulian transitional waters. Case study: Lagoons of Lesina and Varano (Italy). Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2020, 23, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi Aubry, F.; Acri, F.; Finotto, S.; Pugnetti, A. Phytoplankton Dynamics and Water Quality in the Venice Lagoon. Water 2021, 13, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominik, J.; Leoni, S.; Cassin, D.; Guarneri, I.; Bellucci, L.G.; Zonta, R. Eutrophication history and organic carbon burial rate recorded in sediment cores from the Mar Piccolo of Taranto (Italy). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 56713–56730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Palmieri, R.; Porrello, S.; Tomassetti, P. Restoration of the Orbetello lagoon (Tyrrhenian coast, Italy): Water quality management. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2005, 15, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focardi, S.; Mariottini, M.; Renzi, M.; Perra, G.; Focardi, S.E. Anthropogenic impacts on the Orbetello lagoon ecosystem. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2009, 25, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouineau, H.; Durif, C.; Castonguay, M.; Mateo, M.; Rochard, E.; Verreault, G.; Yokouchi, K.; Lambert, P. Freshwater eels: A symbol of the effects of global change. Fish Fish. 2018, 19, 903–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschonitis, V.; Castaldelli, G.; Lanzoni, M.; Rossi, R.; Kennedy, C.; Fano, E.A. Long-term records (1781–2013) of European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) production in the Comacchio Lagoon (Italy): Evaluation of local and global factors as causes of the population collapse. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2017, 27, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molner, J.V.; Soria, J.M.; Pérez-González, R.; Sòria-Perpinyà, X. Estimating Water Transparency Using Sentinel-2 Images in a Shallow Hypertrophic Lagoon (The Albufera of Valencia, Spain). Water 2023, 15, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molner, J.V.; Mellinas-Coperias, I.; Canós-López, C.; Pérez-González, R.; Sendra, M.D.; Soria, J.M. Seasonal Dynamics and Environmental Drivers of Phytoplankton in the Albufera Coastal Lagoon (Valencia, Spain). Environments 2025, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vittor, C.; Faganeli, J.; Emili, A.; Covelli, S.; Predonzani, S.; Acquavita, A. Benthic fluxes of oxygen, carbon and nutrients in the Marano and Grado Lagoon (northern Adriatic Sea, Italy). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 113, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, E.; Cacciatore, F.; Bernarello, V.; Boscolo Brusà, R.; Novello, M.; Sfriso, A.; Strazzabosco, F.; Cornello, M.; Bonometto, A. Assessment of the Trophic Status and Trend Using the Transitional Water Eutrophication Assessment Method: A Case Study from Venice Lagoon. Environments 2024, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.; Caniego, G.; Hernández-Sáez, N.; Dominguez-Gomez, J.A.; Erena, M. Phytoplankton Distribution in Mar Menor Coastal Lagoon (SE Spain) during 2017. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, I.; Roca, M.; Santos-Echeandía, J.; Bernárdez, P.; Navarro, G. Use of the Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Satellites for Water Quality Monitoring: An Early Warning Tool in the Mar Menor Coastal Lagoon. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.Z.A.; Gharib, S.M. Spatial and temporal patterns of phytoplankton composition in Burullus Lagoon, Southern Mediterranean Coast, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2014, 40, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, A.A.; El-Horiny, M.M.; Khairy, H.M.; El-Sheekh, M.M. Phytoplankton dynamics and renewable energy potential induced by the environmental conditions of Lake Burullus, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 66043–66071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inácio, M.; Barboza, F.R.; Villoslada, M. The protection of coastal lagoons as a nature-based solution to mitigate coastal floods. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 34, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Peng, Y.; Grossi, A.A.; Pang, Z.; Zou, F. Lower reclamation of coastal lagoon conserves higher waterbird assemblage phylogenetic diversity. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 62, e03803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Behja, H.; El M’rini, A.; Nachite, D.; Bouchkara, M.; El Khalidi, K.; Zourarah, B.; Uddin, M.G.; Abioui, M. Evaluating coastal lagoon sustainability through the driver-pressure-state-impact-response approach: A study of Khenifiss Lagoon, southern Morocco. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1322749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereher, M.; Salem, M.; Darwish, D. Mapping water quality of Burullus Lagoon using remote sensing and geographic information system. J. Am. Sci. 2011, 7, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Erena, M.; Domínguez, J.A.; Aguado-Giménez, F.; Soria, J.; García-Galiano, S. Monitoring coastal lagoon water quality through remote sensing: The Mar Menor as a case study. Water 2019, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, C.; Galeone, C.; Savino, I.; Campanale, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Towards Sustainable Management of Mussel Farming through High-Resolution Images and Open Source Software—The Taranto Case Study. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsico, A.; Rizzo, A.; Capolongo, D.; De Giosa, F.; Di Leo, A.; Lisco, S.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Moretti, M.; Scardino, G.; Scicchitano, G. Spatial Distribution of Trace Elements in Sub-Surficial Marine Sediments: New Insights from Bay I of the Mar Piccolo of Taranto (Southern Italy). Water 2023, 15, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabal, N.; Puche, E.; Armenta, S.; García-Atienza, P.; Rodrigo, M.A. Constructed wetlands for the mitigation of pesticide and heavy metal concentrations in a protected agrolandscape: Removal efficiencies and ecological risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1001, 180466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.; Rosińska, J.; Wejnerowski, Ł.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Joniak, T. Submerged macrophyte self-recovery potential behind restoration treatments: Sources of failure. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1421448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Roy, D.P.; Zhang, H.; Yan, L.; Huang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. Assessing global Sentinel-2 coverage dynamics and data availability for operational Earth observation applications using the EO-Compass. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezonik, P.L.; Menken, K.D.; Bauer, M.E. Landsat-based remote sensing of lake water quality characteristics, including chlorophyll and colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM). Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 94, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grendaitė, D.; Stonevičius, E. Uncertainty of atmospheric correction algorithms for chlorophyll α concentration retrieval in lakes from Sentinel-2 data. Geocarto Int. 2021, 37, 6867–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molner, J.V.; Pérez-González, R.; Sòria-Perpinyà, X.; Soria, J. Climatic Influence on the Carotenoids Concentration in a Mediterranean Coastal Lagoon Through Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Sea Basin | Lat. | Long. | Perim. (km) | Area (km2) | Depth (m) | Open (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabras | Tyrrhenian | 39.94 | 8.48 | 33.75 | 23.66 | 2 | 204 |

| Orbetello | Tyrrhenian | 42.45 | 11.21 | 21.47 | 14.02 | 1 | 70 |

| Orbetello−Levante | Tyrrhenian | 42.45 | 11.21 | 16.19 | 10.95 | 1 | 20 |

| Mare Piccolo | Ionian | 40.48 | 17.28 | 25.17 | 21.20 | 13 | 142 |

| Varano | Adriatic | 41.88 | 15.74 | 34.97 | 65.52 | 1 | 56 |

| Lesina | Adriatic | 41.88 | 15.45 | 52.23 | 51.01 | 3 | 27 |

| Comacchio | Adriatic | 44.60 | 12.18 | 51.79 | 147.53 | 2 | 48 |

| Venezia | Adriatic | 45.40 | 12.30 | 148.20 | 563.69 | 22 | 1730 |

| Marano−Grado | Adriatic | 45.74 | 13.20 | 80. 11 | 160.96 | 6 | 1788 |

| Conc_chl | Conc_tsm | kd_z90max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 181 | 181 | 181 |

| Min | 0.44 | 0.93 | 0.26 |

| Max | 80.81 | 47.64 | 9.37 |

| Mean | 15.41 | 15.09 | 1.51 |

| Variance | 191.03 | 112.70 | 2.30 |

| Stand. dev | 13.82 | 10.62 | 1.52 |

| Median | 10.51 | 12.44 | 0.90 |

| 25 prcntil | 6.90 | 8.88 | 0.54 |

| 75 prcntil | 20.54 | 18.40 | 1.51 |

| Skewness | 1.85 | 1.29 | 2.10 |

| Kurtosis | 4.58 | 1.40 | 4.68 |

| Coeff. var | 89.72 | 70.33 | 100.43 |

| Cabras | Orbetello | Orbetello-Levante | Mare Piccolo | Varano | Lesina | Comacchio | Venezia | Marano-Grado | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Min | 10.30 | 8.38 | 4.23 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 8.69 | 10.20 | 3.93 | 6.57 |

| Max | 42.64 | 23.90 | 20.65 | 2.77 | 17.84 | 47.78 | 80.81 | 10.24 | 24.17 |

| Mean | 27.23 | 15.27 | 12.59 | 1.43 | 5.47 | 20.78 | 37.83 | 7.43 | 10.66 |

| Std. error | 2.22 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 1.08 | 2.33 | 4.19 | 0.33 | 1.03 |

| Variance | 98.75 | 21.76 | 21.37 | 0.56 | 23.17 | 97.36 | 368.18 | 2.35 | 22.34 |

| Stand. dev | 9.94 | 4.67 | 4.62 | 0.75 | 4.81 | 9.87 | 19.19 | 1.53 | 4.73 |

| Median | 28.63 | 15.09 | 12.14 | 1.19 | 3.25 | 21.06 | 32.92 | 7.53 | 8.83 |

| 25 prcntil | 17.51 | 10.50 | 9.99 | 0.91 | 1.57 | 11.46 | 24.13 | 6.67 | 7.50 |

| 75 prcntil | 36.39 | 19.23 | 16.40 | 2.22 | 8.98 | 24.77 | 50.18 | 8.36 | 12.63 |

| Skewness | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 0.79 | −0.24 | 1.70 |

| Kurtosis | −1.13 | −0.87 | −0.59 | −1.21 | 0.62 | 1.98 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 2.53 |

| Chl-a | TSM | kd_z90max | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Z | p | S | Z | p | S | Z | p | |

| Cabras | 66 | 2.11 | 0.03 * | 14 | 0.42 | 0.67 n.s | −23 | −0.71 | 0.48 n.s |

| Orbetello | 20 | 0.62 | 0.54 n.s | −18 | −0.55 | 0.58 n.s | −4 | −0.1 | 0.92 n.s |

| Orbetello-Levante | 36 | 1.14 | 0.26 n.s | −48 | −1.52 | 0.13 n.s | 14 | 0.42 | 0.67 n.s |

| Mare Piccolo | −11 | −0.32 | 0.75 n.s. | −7 | −0.19 | 0.85 n.s. | −19 | −0.58 | 0.56 n.s. |

| Varano | 76 | 2.43 | 0.01 * | 82 | 2.63 | 0.008 ** | −72 | −2.30 | 0.02 * |

| Lesina | 40 | 1.61 | 0.11 n.s. | 30 | 1.1946 | 0.23 n.s | −28 | −1.11 | 0.27 n.s. |

| Comacchio | 4 | 0.09 | 0.93 n.s. | −34 | −1.0 | 0.32 n.s. | −19 | −0.54 | 0.59 n.s. |

| Venezia | −2 | −0.03 | 0.97 n.s | 30 | 0.88 | 0.38 n.s | −35 | −1.03 | 0.3 n.s |

| Marano-Grado | −6 | −0.15 | 0.88 n.s | 2 | 0.03 | 0.98 n.s | 24 | 0.69 | 0.49 n.s |

| Date | Cabras | Orbetello | Orbetello- Levante | Mare Piccolo | Varano | Lesina | Comacchio | Venezia | Marano- Grado |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer 2015 | 7.53 | 20.37 | |||||||

| Winter 2015–2016 | 10.30 | 13.58 | 10.14 | 1.12 | 6.27 | 29.84 | 6.90 | 7.97 | |

| Summer 2016 | 17.31 | 20.28 | 11.82 | 2.39 | 1.44 | 58.36 | 7.77 | 9.92 | |

| Winter 2016–2017 | 35.67 | 9.36 | 7.03 | 0.90 | 1.20 | 10.38 | 32.17 | 7.26 | 7.45 |

| Summer 2017 | 22.48 | 16.28 | 13.75 | 2.47 | 1.52 | 23.60 | 17.33 | 6.45 | 10.46 |

| Winter 2017–2018 | 41.17 | 12.35 | 10.32 | 0.96 | 3.49 | 8.69 | 38.37 | 8.13 | 7.15 |

| Summer 2018 | 15.52 | 19.53 | 12.45 | 1.49 | 0.45 | 21.73 | 49.15 | 7.80 | 10.51 |

| Winter 2018–2019 | 11.66 | 9.87 | 14.49 | 2.50 | 5.50 | 9.24 | 10.20 | 5.66 | 7.54 |

| Summer 2019 | 42.64 | 16.29 | 10.05 | 0.61 | 2.32 | 20.52 | 80.81 | 7.61 | 15.47 |

| Winter 2019–2020 | 15.47 | 8.38 | 6.26 | 2.30 | 2.82 | 11.11 | 51.20 | 7.22 | 6.82 |

| Summer 2020 | 31.10 | 18.33 | 10.16 | 1.03 | 1.74 | 24.45 | 32.92 | 9.22 | 13.36 |

| Winter 2020–2021 | 23.56 | 14.96 | 14.36 | 1.08 | 3.00 | 16.45 | 33.95 | 5.47 | 6.57 |

| Summer 2021 | 18.11 | 8.78 | 4.23 | 0.49 | 2.97 | 19.33 | 60.59 | 10.24 | 15.56 |

| Winter 2021–2022 | 28.80 | 15.22 | 20.23 | 1.25 | 11.43 | 14.73 | 24.46 | 5.39 | 8.28 |

| Summer 2022 | 27.99 | 23.90 | 19.46 | 0.44 | 4.56 | 31.03 | 16.83 | 8.59 | 11.89 |

| Winter 2022–2023 | 37.10 | 17.12 | 17.58 | 1.35 | 11.89 | 32.77 | 28.14 | 8.58 | 7.63 |

| Summer 2023 | 30.76 | 14.04 | 9.27 | 0.95 | 17.84 | 23.35 | 45.29 | 10.07 | 24.17 |

| Winter 2023–2024 | 32.34 | 20.55 | 20.65 | 1.99 | 8.59 | 25.73 | 23.79 | 8.03 | 6.90 |

| Summer 2024 | 28.45 | 22.74 | 12.50 | 2.77 | 9.11 | 21.59 | 42.41 | 7.29 | 9.20 |

| Winter 2024–2025 | 36.63 | 9.88 | 17.03 | 1.96 | 12.14 | 11.58 | 25.83 | 6.88 | 7.84 |

| Summer 2025 | 37.59 | 14.03 | 9.97 | 0.61 | 1.10 | 47.78 | 75.33 | 3.93 | 8.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagliani, V.; Arnau-López, E.; Campillo-Tamarit, N.; Muñoz-Colmenares, M.; Soria, J.M.; Molner, J.V. Environmental Degradation in the Italian Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons Shown by Satellite Imagery. Phycology 2025, 5, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040087

Pagliani V, Arnau-López E, Campillo-Tamarit N, Muñoz-Colmenares M, Soria JM, Molner JV. Environmental Degradation in the Italian Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons Shown by Satellite Imagery. Phycology. 2025; 5(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040087

Chicago/Turabian StylePagliani, Viola, Elena Arnau-López, Noelia Campillo-Tamarit, Manuel Muñoz-Colmenares, Juan Miguel Soria, and Juan Víctor Molner. 2025. "Environmental Degradation in the Italian Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons Shown by Satellite Imagery" Phycology 5, no. 4: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040087

APA StylePagliani, V., Arnau-López, E., Campillo-Tamarit, N., Muñoz-Colmenares, M., Soria, J. M., & Molner, J. V. (2025). Environmental Degradation in the Italian Mediterranean Coastal Lagoons Shown by Satellite Imagery. Phycology, 5(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040087