Insecticidal Activity of Eco-Extracted Holopelagic Sargassum Against the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Infesting Tomato Crops

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algal Biomass Collection and Pretreatments

2.2. Extraction

2.2.1. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

2.2.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis (UAEH)

- -

- Protease Batch: a mixture of Flavourzyme (Novozymes, Bagsværd, Denmark), Maxipro NPU (DSM, Delft, Netherlands), Neutrase (Novozymes), and Protamex (Novozymes), also used at optimal conditions of 50 °C and pH 6.5.

- -

- Carbohydrase Batch: a blend of five enzymes, including Glucanex (Novozymes), Sumizyme (Shin Nihon Chemicals Co., Anjyo Aichi, Japan), Termamyl (Novozymes), and Ultraflo L (Novozymes), applied under optimal conditions of 50 °C and pH 6.5.

2.3. Biochemical Composition Analysis

2.4. Evaluation of Biological Activity

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical Composition

3.1.1. Raw Seaweed Biomass

3.1.2. Seaweed Extracts

3.2. Biological Activity of Seaweed Extracts

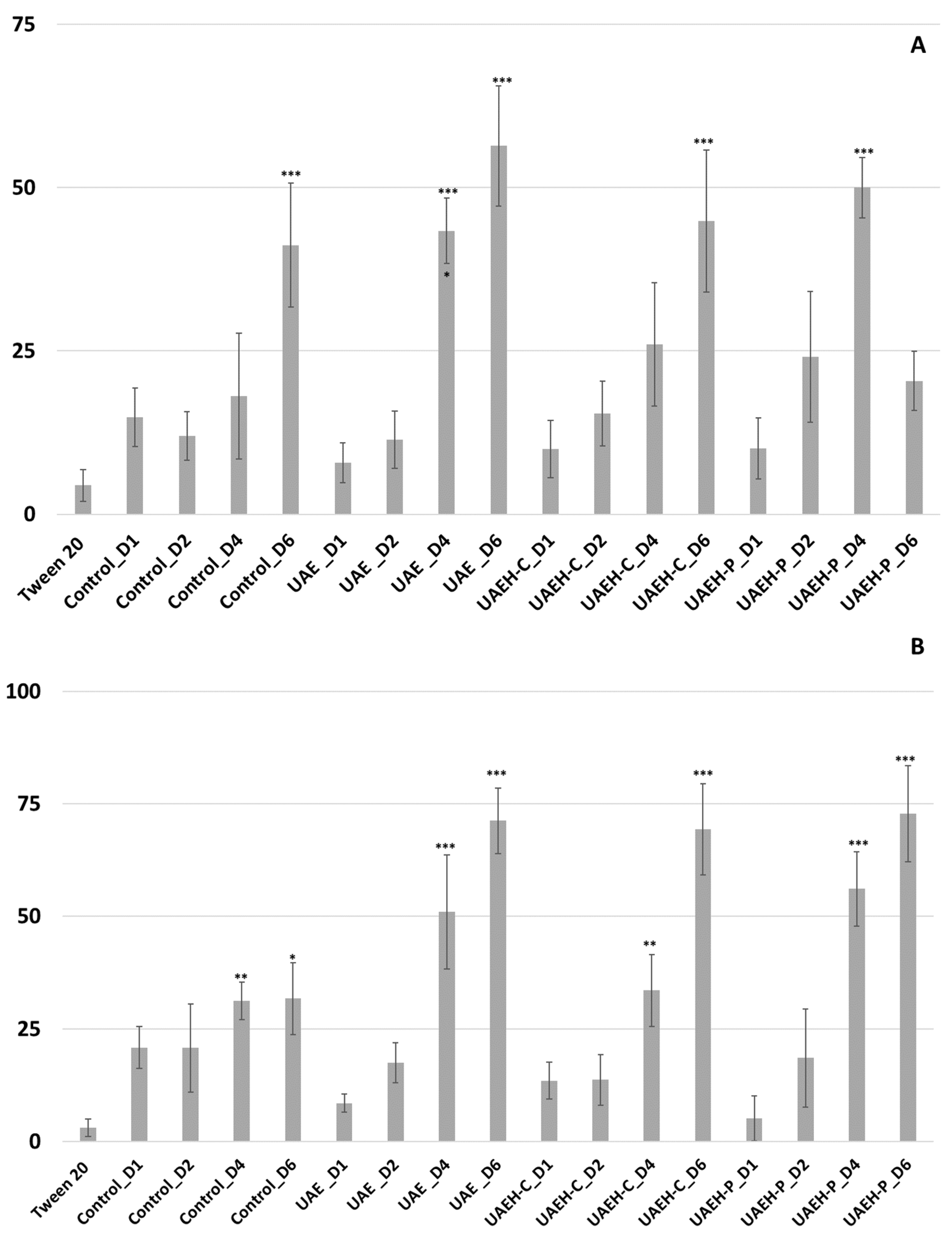

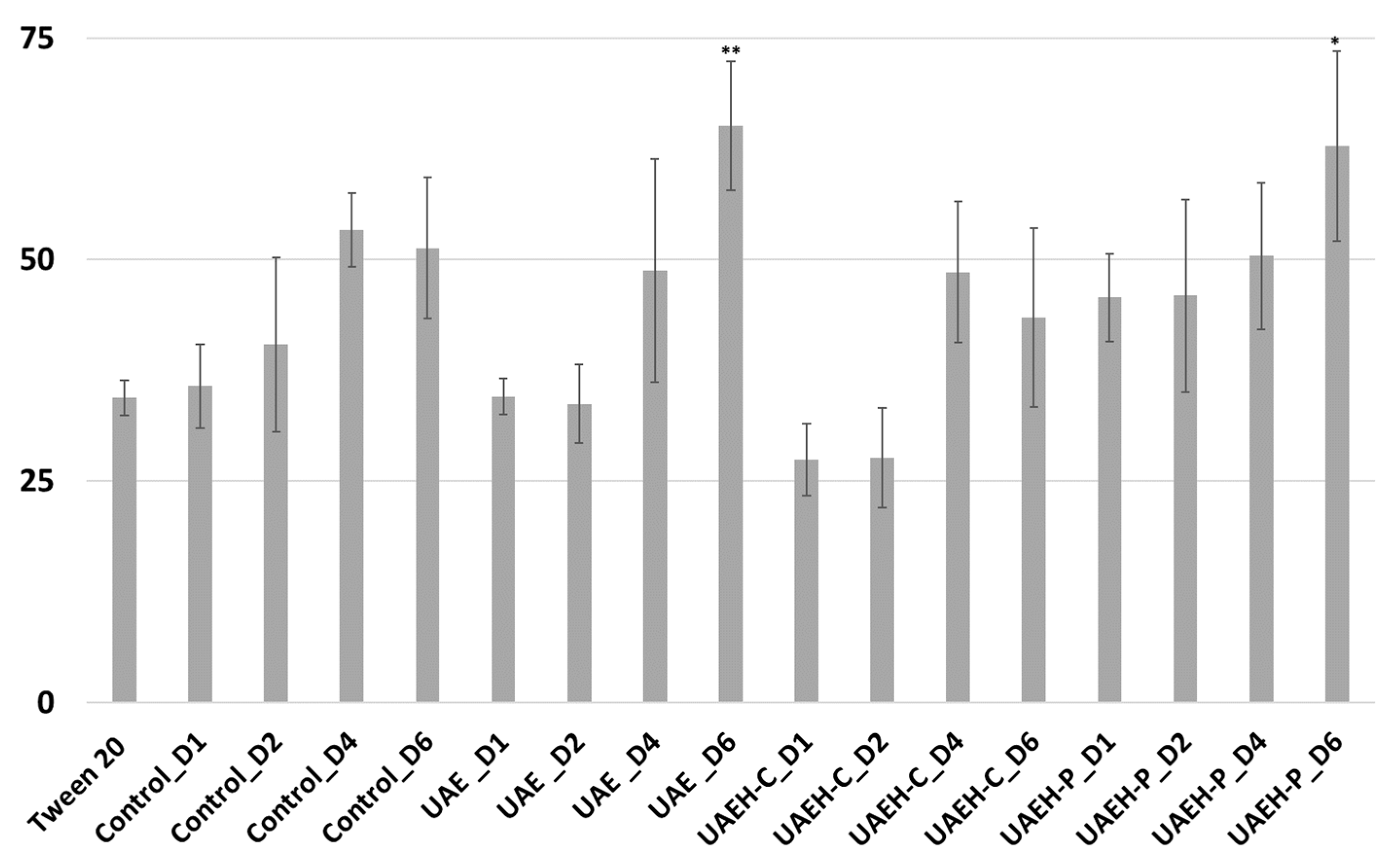

3.2.1. Biocidal Activity on Adult Whiteflies

3.2.2. Ovicidal Activity on the Immature Stages of Whiteflies (Eggs)

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization of Sargassum Biomass and Extracts

4.2. Biological Activities of Sargassum Extracts

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Mitchum, G.; Lapointe, B.; Montoya, J.P. The great Atlantic Sargassum belt. Science 2019, 365, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatier, M.; Duchaudé, Y.; Lanoir, R.; Thesnor, V.; Sylvestre, M.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G.; Vega-Rúa, A. Invasive brown algae (Sargassum spp.) as a potential source of biocontrol against Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comité Indépendant d’Experts sur la problématique Sargasses et en Martinique. Echouements massifs sargasses Martinique en 2025: Enjeux prioritaires concernant le collège Robert 3 (Pontalery) et d’autres établissements sco-laires impactés. Available online: https://www.madinin-art.net/data/Rapport-Comite-Sargasses-16-05-2025_final.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Resiere, D.; Mehdaoui, H.; Florentin, J.; Gueye, P.; Lebrun, T.; Blateau, A.; Viguier, J.; Valentino, R.; Brouste, Y.; Kallel, H.; et al. Sargassum seaweed health menace in the Caribbean: Clinical characteristics of a population exposed to hydrogen sulfide during the 2018 massive stranding. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 59, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardouin, K.; Bedoux, G.; Burlot, A.-S.; Donnay-Moreno, C.; Bergé, J.-P.; Nyvall-Collén, P.; Bourgougnon, N. Enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE) for the production of antiviral and antioxidant extracts from the green seaweed Ulva armoricana (Ulvales, Ulvophyceae). Algal Res. 2016, 16, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador-Castro, F.; García-Cayuela, T.; Alper, H.S.; Rodriguez-Martinez, V.; Carrillo-Nieves, D. Valorization of pelagic Sargassum biomass into sustainable applications: Current trends and challenges. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.; March, A.; Li, H.; Lallemand, P.; Maréchal, J.-P.; Failler, P. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of Sargassum valorisation solutions for the Caribbean. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 381, 124954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniaud-Bouët, E.; Kervarec, N.; Michel, G.; Tonon, T.; Kloareg, B.; Hervé, C. Chemical and enzymatic fractionation of cell walls from Fucales: Insights into the structure of the extracellular matrix of brown algae. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vaquero, M.; Ummat, V.; Tiwari, B.; Rajauria, G. Exploring Ultrasound, Microwave and Ultrasound–Microwave Assisted Extraction Technologies to Increase the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidants from Brown Macroalgae. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadar, S.S.; Rathod, V.K. Ultrasound assisted intensification of enzyme activity and its properties: A mini-review. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A.; Geertman, R.; Wierschem, M.; Skiborowski, M.; Gielen, B.; Jordens, J.; John, J.J.; Van Gerven, T. Ultrasound-assisted emerging technologies for chemical processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, C.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Miao, N.; Shi, Y.; Ri, I.; Wang, W.; Wang, H. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted enzymatic pretreatment for enhanced extraction of baicalein and wogonin from Scutellaria baicalensis roots. J. Chromatogr. B 2022, 1188, 123077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Castro, A.L.; Muñoz-Ochoa, M.; Hernández-Carmona, G.; López-Vivas, J.M. Evaluation of seaweed extracts for the control of the Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 3815–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisha, J.M.; Srinivasan, G.; Shanthi, M.; Mini, M.L.; Vellaikumar, S.; Sujatha, K. Phytochemical profiling and toxicity effect of various seaweed species against diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2023, 43, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchidurai, G.; Sahayaraj, K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Albogami, B.Z.; Sayed, S.M. Insecticidal Activity of Tannins from Selected Brown Macroalgae against the Cotton Leafhopper Amrasca devastans. Plants 2023, 12, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashwan, R.S.; Hammad, D.M. Toxic effect of Spirulina platensis and Sargassum vulgar as natural pesticides on survival and biological characteristics of cotton leaf worm Spodoptera littoralis. Sci. Afr. 2020, 8, e00323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mbata, G.N.; Simmons, A.M.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Wu, S. Management of Bemisia tabaci on vegetable crops using entomopathogens. Crop Prot. 2024, 180, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.R.V.; Henneberry, T.J.; Anderson, P. History, current status, and collaborative research projects for Bemisia tabaci. Crop Prot. 2001, 20, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalappara, S.R.; Milner, H.; Konakalla, N.C.; Morgan, K.; Sparks, A.N.; McCregor, C.; Culbreath, A.K.; Wintermantel, W.M.; Bag, S. High Throughput Sequencing-Aided Survey Reveals Widespread Mixed Infections of Whitefly-Transmitted Viruses in Cucurbits in Georgia, USA. Viruses 2021, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radouane, N.; Ezrari, S.; Belabess, Z.; Tahiri, A.; Tahzima, R.; Massart, S.; Jijakli, H.; Benjelloun, M.; Lahlali, R. Viruses of cucurbit crops: Current status in the Mediterranean Region. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2021, 60, 493–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmão, M.R.; Picanço, M.C.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Galvan, T.L.; Pereira, E.J.G. Economic injury level and sequential sampling plan for Bemisia tabaci in outdoor tomato. J. Appl. Entomol. 2006, 130, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mbata, G.N.; Punnuri, S.; Simmons, A.M.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I. Bemisia tabaci on vegetables in the southern United States: Incidence, impact, and management. Insects 2021, 12, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrosso, S.E.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Mbega, E.R. Farmers’ knowledge on Whitefly Populousness among tomato insect pests and their management options in tomato in Tanzania. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terme, N.; Hardouin, K.; Cortès, H.P.; Peñuela, A.; Freile-Pelegrín, Y.; Robledo, D.; Bedoux, G.; Bourgougnon, N. Emerging seaweed extraction techniques: Enzyme-assisted extraction a key step of seaweed biorefinery? In Sustainable Seaweed Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 225–256. ISBN 978-0-12-817943-7. [Google Scholar]

- Romarís-Hortas, V.; Bermejo-Barrera, P.; Moreda-Piñeiro, A. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis for iodinated amino acid extraction from edible seaweed before reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography–inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1309, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guillard, C.; Bergé, J.-P.; Donnay-Moreno, C.; Cornet, J.; Ragon, J.-Y.; Fleurence, J.; Dumay, J. Optimization of R-Phycoerythrin Extraction by Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis: A Comprehensive Study on the Wet Seaweed Grateloupia turuturu. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filisetti-Cozzi, T.M.C.C.; Carpita, N.C. Measurement of uronic acids without interference from neutral sugars. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 197, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Krohn, R.I.; Hermanson, G.T.; Mallia, A.K.; Gartner, F.H.; Provenzano, M.D.; Fujimoto, E.K.; Goeke, N.M.; Olson, B.J.; Klenk, D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985, 150, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.E.; Butler, L.G. Choosing appropriate methods and standards for assaying tannin. J. Chem. Ecol. 1989, 15, 1795–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaques, L.B.; Balueux, R.E.; Dietrich, C.P.; Kavanagh, L.W. A microelectrophoresis method for heparin. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1968, 46, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardouin, K.; Burlot, A.-S.; Umami, A.; Tanniou, A.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Widowati, I.; Bedoux, G.; Bourgougnon, N. Biochemical and antiviral activities of enzymatic hydrolysates from different invasive French seaweeds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenheim, J.A.; Hoy, M.A. Confidence intervals for the Abbott’s formula correction of bioassay data for control response. J. Econ. Entomol. 1989, 82, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Lei, C.; Sun, X. Comparison of lethal doses calculated using logit/probit–log(dose) regressions with arbitrary slopes Using R. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.B.; Maddix, G.-M.; Francis, P.; Thomas, S.-L.; Burton, J.-A.; Langer, S.; Larson, T.R.; Marsh, R.; Webber, M.; Tonon, T. Pelagic Sargassum events in Jamaica: Provenance, morphotype abundance, and influence of sample processing on biochemical composition of the biomass. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliego-Cortés, H.; Boy, V.; Bourgougnon, N. Instant Controlled Pressure Drop (DIC) as an innovative pre-treatment for extraction of natural compounds from the brown seaweed Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt 1955 (Ochrophytina, Fucales). Algal Res. 2024, 83, 103705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga-Hernandez, S.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Carrillo-Nieves, D.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Seasonal characterization and quantification of biomolecules from Sargassum collected from Mexican Caribbean coast—A preliminary study as a step forward to blue economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonon, T.; Machado, C.B.; Webber, M.; Webber, D.; Smith, J.; Pilsbury, A.; Cicéron, F.; Herrera-Rodriguez, L.; Jimenez, E.M.; Suarez, J.V.; et al. Biochemical and Elemental Composition of Pelagic Sargassum Biomass Harvested across the Caribbean. Phycology 2022, 2, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milledge, J.; Harvey, P. Golden tides: Problem or golden opportunity? The valorisation of Sargassum from beach inundations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2016, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.-E.; Turgeon, S.L. Seaweed carbohydrates. In Seaweed Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 141–192. ISBN 978-0-12-418697-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Bourgougnon, N.; Deslandes, E. Carbohydrates From Seaweeds. In Seaweed in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 223–274. ISBN 978-0-12-802772-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fleurence, J. Seaweed proteins. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, A.R.; Mata, L.; De Nys, R.; Paul, N.A. The protein content of seaweeds: A universal nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of five. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choulot, M.; Jabbour, C.; Burlot, A.-S.; Jing, L.; Welna, M.; Szymczycha-Madeja, A.; Le Guillard, C.; Michalak, I.; Bourgougnon, N. Application of enzyme-assisted extraction on the brown seaweed Fucus vesiculosus Linnaeus (Ochrophyta, Fucaceae) to produce extracts for a sustainable agriculture. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.V.; Milledge, J.J.; Hertler, H.; Maneein, S.; Al Farid, M.M.; Bartlett, D. Chemical characterisation of Sargassum inundation from the Turks and Caicos: Seasonal and post stranding changes. Phycology 2021, 1, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspita, M.; Déniel, M.; Widowati, I.; Radjasa, O.K.; Douzenel, P.; Marty, C.; Vandanjon, L.; Bedoux, G.; Bourgougnon, N. Total phenolic content and biological activities of enzymatic extracts from Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2521–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouguerné, E.; Cesconetto, C.; Cruz, C.P.; Pereira, R.C.; Da Gama, B.A.P. Within-thallus variation in polyphenolic content and antifouling activity in Sargassum vulgare. J. Appl. Phycol. 2012, 24, 1629–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rodríguez, A.; Mawhinney, T.P.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Cruz-Suárez, L.E. Chemical composition of cultivated seaweed Ulva clathrata (Roth) C. Agardh. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, M.P.; Conde, E.; Domínguez, H.; Moure, A. Ecofriendly extraction of bioactive fractions from Sargassum muticum. Process Biochem. 2019, 79, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Lu, F.; Liu, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Multi-Enzyme Extraction for highly efficient extraction of poly-saccharides from Ulva lactuca. Foods 2024, 13, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Jasso, R.M.; Mussatto, S.I.; Pastrana, L.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Microwave-assisted extraction of sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidan) from brown seaweed. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiono, S.; Taufiq Hidayat, M.; Alrosyidi, F.; Nur Abadi, A.; Anam, K.; Zannuba, S.; Taufiky, A.; Hoiriyah, E.; Nugroho, M. Microwave Assisted Extraction in a sequential biorefinery of alginate and fucoidan from Brown Alga Sargassum cristaefolium. Food Sci. Technol. J. Foodscitech 2022, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Cassani, L.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Grosso, C.; Chamorro, F.; García-Pérez, P.; Carvalho, A.; Domingues, V.F.; Barroso, M.F.; et al. Exploring the potential of invasive species Sargassum muticum: Microwave-Assisted Extraction optimization and bioactivity Profiling. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaëlle, T.; Serrano Leon, E.; Laurent, V.; Elena, I.; Mendiola, J.A.; Stéphane, C.; Nelly, K.; Stéphane, L.B.; Luc, M.; Valérie, S.-P. Green improved processes to extract bioactive phenolic compounds from brown macroalgae using Sargassum muticum as model. Talanta 2013, 104, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Lee, J.W.; Ho, T.C.; Park, Y.; Ata, S.M.; Yun, H.J.; Gang, G.; Getachew, A.T.; Chun, B.-S.; Lee, S.G.; et al. A comparative study of extraction methods for recovery of bioactive components from brown algae Sargassum serratifolium. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denecke, S.; Swevers, L.; Douris, V.; Vontas, J. How do oral insecticidal compounds cross the insect midgut epithelium? Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 103, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeckel, A.M.; Beran, F.; Züst, T.; Younkin, G.; Petschenka, G.; Pokharel, P.; Dreisbach, D.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C.; Robert, C.A.M. Metabolization and sequestration of plant specialized metabolites in insect herbivores: Current and emerging approaches. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1001032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, M.; Koul, B.; Chandrashekar, K.; Raut, A.; Yadav, D. Whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) Management (WFM) strategies for sustainable agriculture: A review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateyyat, M.A.; Al-Mazra’awi, M.; Abu-Rjai, T.; Shatnawi, M.A. Aqueous extracts of some medicinal plants are as toxic as Imidacloprid to the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci. J. Insect Sci. 2009, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldin, E.L.; Fanela, T.L.; Pannuti, L.E.; Kato, M.J.; Takeara, R.; Crotti, A.E. Botanical extracts: Alternative control for silverleaf whitefly management in tomato Extratos botânicos: Controle alternativo para o manejo de mosca-branca em tomateiro. Hortic. Bras. 2015, 33, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.R.; Hwang, H.; Acharya, R.; Kim, D.; Lee, K. Stage-specific susceptibility of Bemisia tabaci MED eggs and neonates to insecticides with different modes of action. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 119, e70087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, J.T.; Srinivasan, G.; Shanthi, M.; Mini, M.L. Multifaceted effects of seaweed extracts against cowpea aphid, Aphis craccivora Koch, by evaluating four macroalgae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matloub, A.A.; Awad, N.E.; Khamiss, O.A. Chemical composition of some Sargassum spp. and their insecticidal evaluation on nucleopolyhedrovirus replication in vitro and in vivo. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2012, 11, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Suganya, S.; Ishwarya, R.; Jayakumar, R.; Govindarajan, M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Al-anbr, M.N.; Vaseeharan, B. New insecticides and antimicrobials derived from Sargassum wightii and Halimeda gracillis seaweeds: Toxicity against mosquito vectors and antibiofilm activity against microbial pathogens. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 125, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aziz, F.E.-Z.A.A.; Hifney, A.F.; Mohany, M.; Al-Rejaie, S.S.; Banach, A.; Sayed, A.M. Insecticidal activity of brown seaweed (Sargassum latifolium) extract as potential chitin synthase inhibitors: Toxicokinetic and molecular docking approaches. S.Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 160, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extract | UAE | Enzyme treatment | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Maceration) | No | No | Control |

| UAE | Yes | No | UAE |

| UAEH-Protease | Yes | Protease mixture | UAEH-P |

| UAEH-Carbohydrase | Yes | Carbohydrase mixture | UAEH-C |

| Sample | Ash % ± sd | Neutral sugars % ± sd | Uronic acids % ± sd | Sulfates % ± sd | Proteins % ± sd | Phenolics % ± sd | Total % ± sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass | 45.22 ± 0.41 | 14.22 ± 0.79 | 5.30 ± 0.04 | 2.12 ± 0.01 | 11.26 ± 0.39 | 3.38 ± 0.11 | 81.50 ± 1.75 |

| Control | 67.72 ± 0.00 | 5.13 ± 0.15 | 5.50 ± 0.07 | 3.33 ± 0.18 | 6.44 ± 0.22 | 1.67 ± 0.04 | 89.79 ± 0.66 |

| UAE | 65.93 ± 0.18 | 5.13 ± 0.02 | 5.00 ± 0.17 | 3.49 ± 0.01 | 6.96 ± 0.17 | 1.54 ± 0.22 | 88.05 ± 0.77 |

| UAEH-C | 61.40 ± 0.51 | 11.54 ± 2.08 | 4.73 ± 0.34 | 1.87 ± 0.01 | 5.12 ± 0.17 | 1.86 ± 0.21 | 86.52 ± 3.32 |

| UAEH-P | 62.33 ± 0.32 | 3.35 ± 0.06 | 2.46 ± 0.05 | 3.60 ± 0.00 | 6.52 ± 0.28 | 1.19 ± 0.05 | 80.34 ± 0.76 |

| Modality | Adults 24 h | Adults 48 h | Eggs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water (natural mortality) | 82 | 81 | 616 |

| Tween 20 (negative control) | 79 | 77 | 623 |

| Control_D1 | 78 | 73 | 593 |

| Control_D2 | 76 | 82 | 616 |

| Control_D4 | 87 | 81 | 669 |

| Control_D6 | 81 | 83 | 595 |

| UAE_D1 | 68 | 67 | 649 |

| UAE_D2 | 75 | 77 | 616 |

| UAE_D4 | 77 | 79 | 604 |

| UAE_D6 | 82 | 80 | 597 |

| UAEH-C_D1 | 86 | 88 | 584 |

| UAEH-C_D2 | 83 | 81 | 555 |

| UAEH-C_D4 | 83 | 77 | 624 |

| UAEH-C_D6 | 89 | 87 | 571 |

| UAEH-P_D1 | 73 | 78 | 551 |

| UAEH-P_D2 | 78 | 60 | 558 |

| UAEH-P_D4 | 79 | 71 | 612 |

| UAEH-P_D6 | 72 | 70 | 585 |

| Extract | LD50 ± se %—(μg. mL−1) | 95% Confidence Interval %—(μg mL−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| B. tabaci adults (after 48 h exposure) | |||

| UAEH-C | 4.5 ± 0.4—(45) | 3.7%—(37) | 5.4%—(54) |

| UAEH-P | 4.0 ± 0.3—(40) | 3.3%—(33) | 4.6%—(46) |

| UAE | 3.9 ± 0.3—(39) | 3.3%—(33) | 4.5%—(45) |

| B. tabaci eggs (7 days after treatment) | |||

| UAEH-P | 1.9 ± 0.3—(19) | 0.7%—(7) | 3.0%—(30) |

| UAE | 2.8 ± 0.3—(28) | 2.3%—(23) | 3.3%—(33) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jabbour, C.; Rhino, B.; Corbanini, C.; Bergé, J.-P.; Hardouin, K.; Bourgougnon, N. Insecticidal Activity of Eco-Extracted Holopelagic Sargassum Against the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Infesting Tomato Crops. Phycology 2025, 5, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040079

Jabbour C, Rhino B, Corbanini C, Bergé J-P, Hardouin K, Bourgougnon N. Insecticidal Activity of Eco-Extracted Holopelagic Sargassum Against the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Infesting Tomato Crops. Phycology. 2025; 5(4):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040079

Chicago/Turabian StyleJabbour, Chirelle, Béatrice Rhino, Chloé Corbanini, Jean-Pascal Bergé, Kevin Hardouin, and Nathalie Bourgougnon. 2025. "Insecticidal Activity of Eco-Extracted Holopelagic Sargassum Against the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Infesting Tomato Crops" Phycology 5, no. 4: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040079

APA StyleJabbour, C., Rhino, B., Corbanini, C., Bergé, J.-P., Hardouin, K., & Bourgougnon, N. (2025). Insecticidal Activity of Eco-Extracted Holopelagic Sargassum Against the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Infesting Tomato Crops. Phycology, 5(4), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040079