Evolution of a Dystrophic Crisis in a Non-Tidal Lagoon Through Microphyte Blooms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

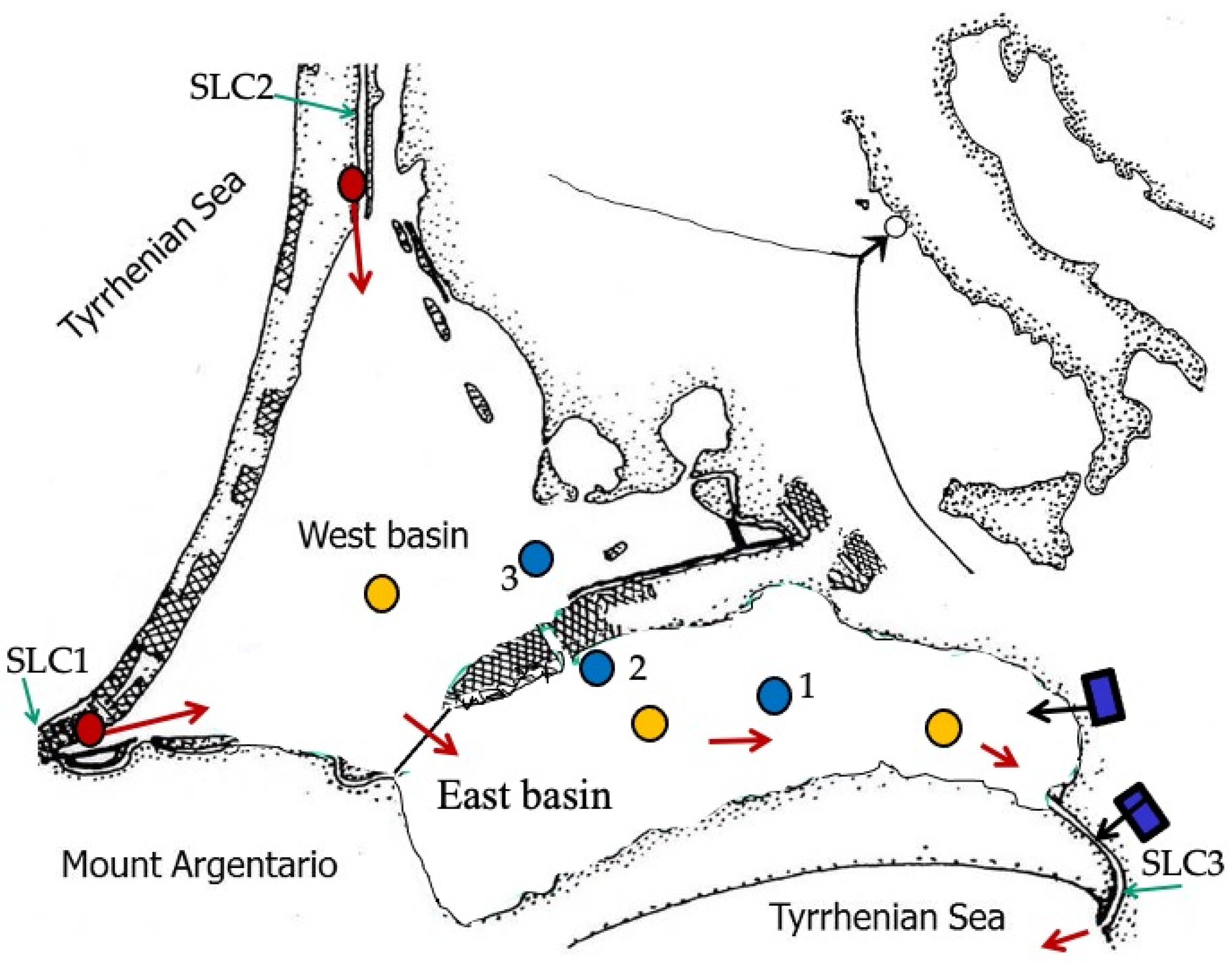

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. Macroalgae Monitoring

2.3. Sediment Organic Matter

2.4. Water Chemical-Physical Variables

2.5. Microphyte Determinations

2.6. Dystrophies

3. Results

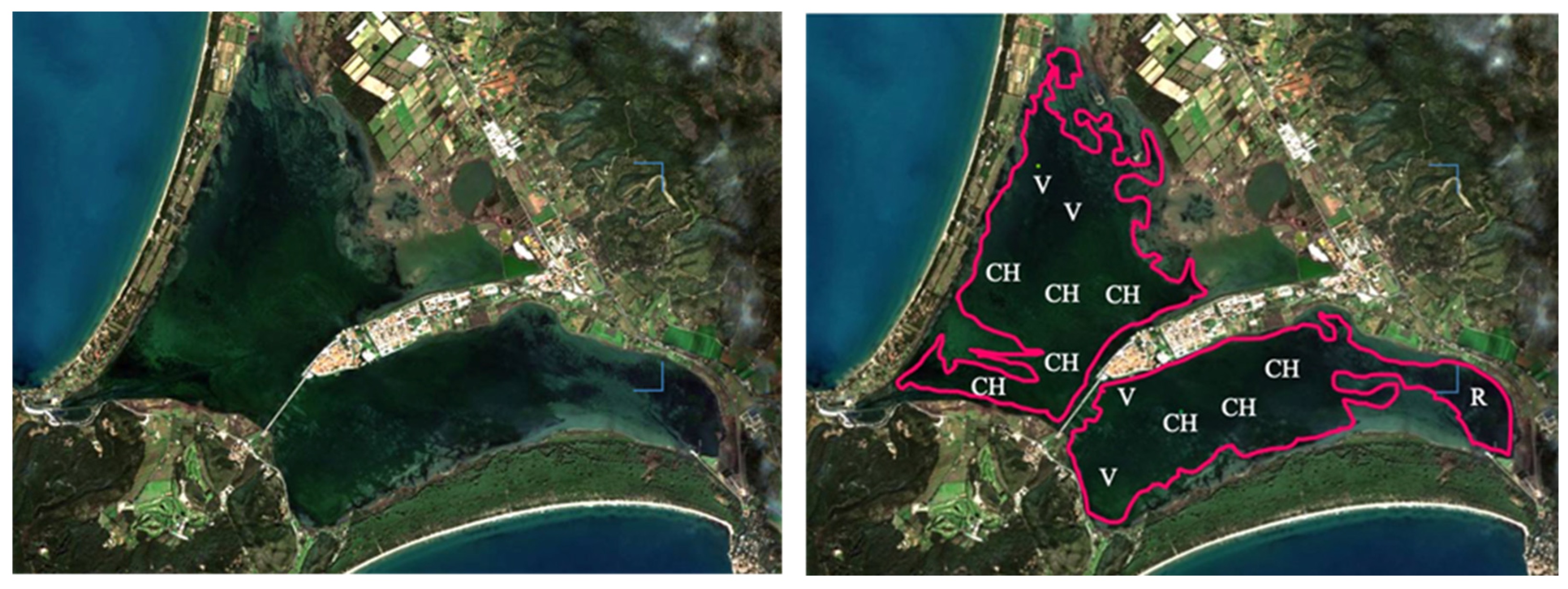

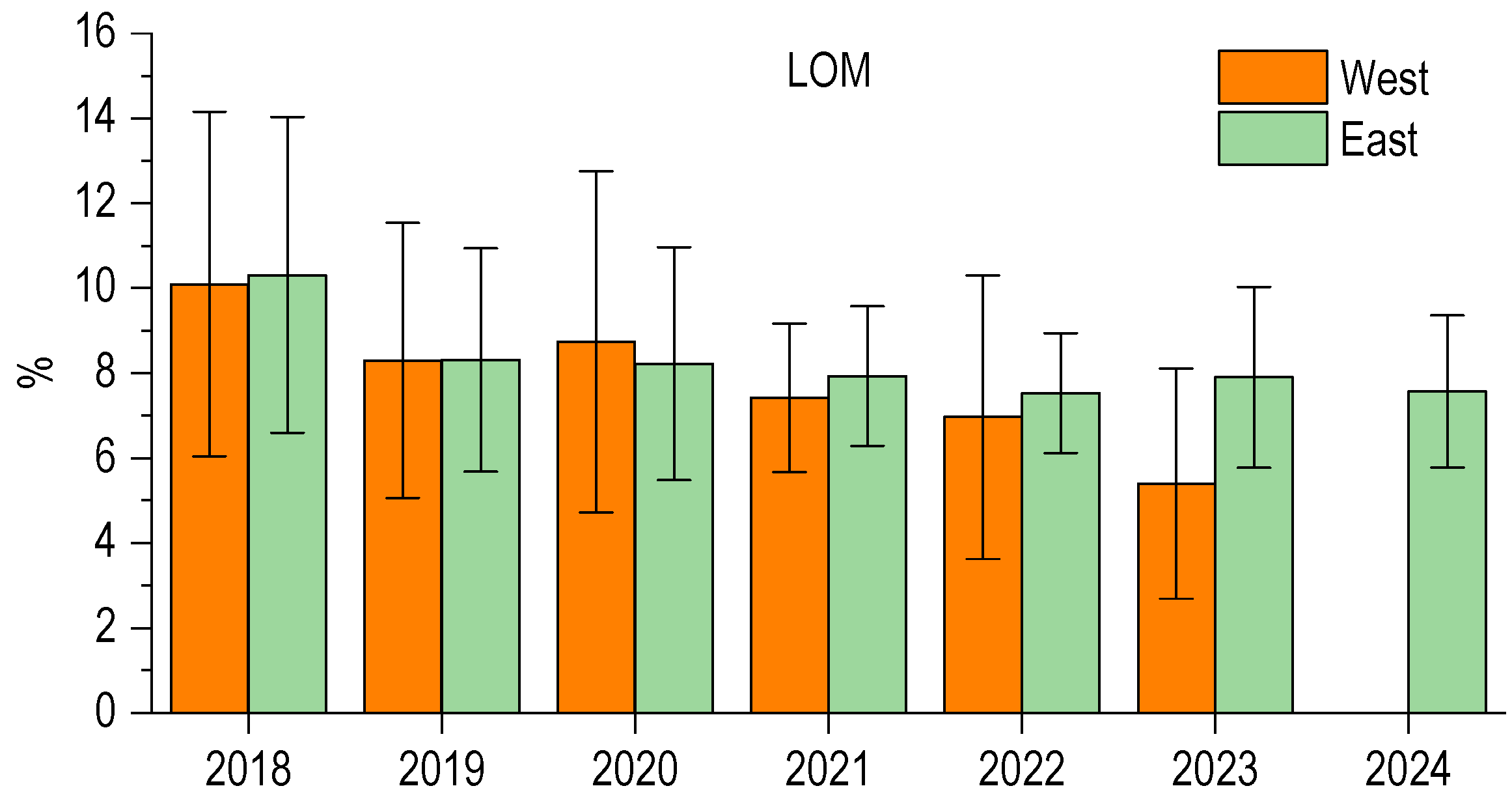

3.1. Macroalgae Monitoring

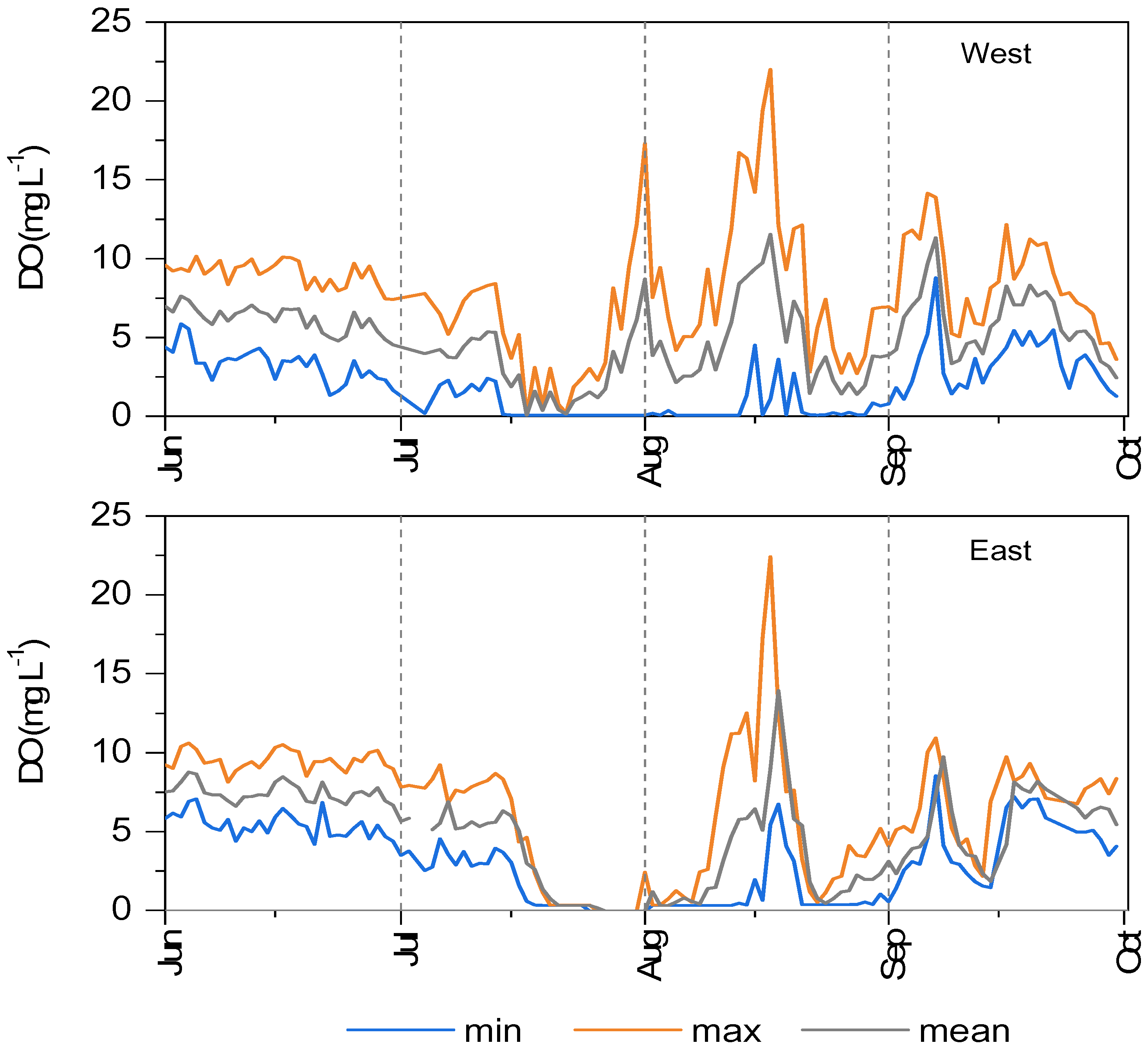

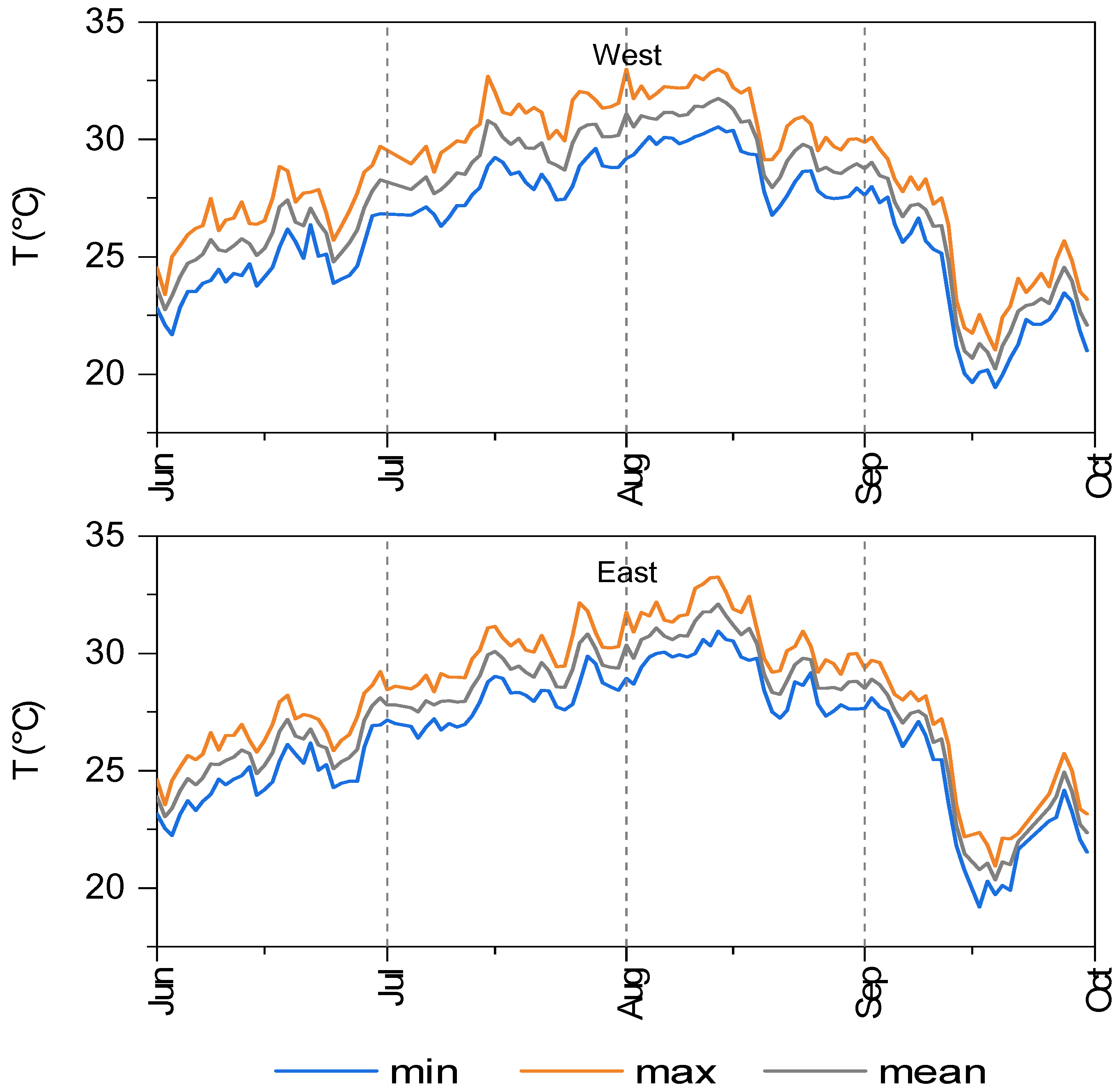

3.2. Water Chemical-Physical Variables

3.3. Sediment Organic Matter

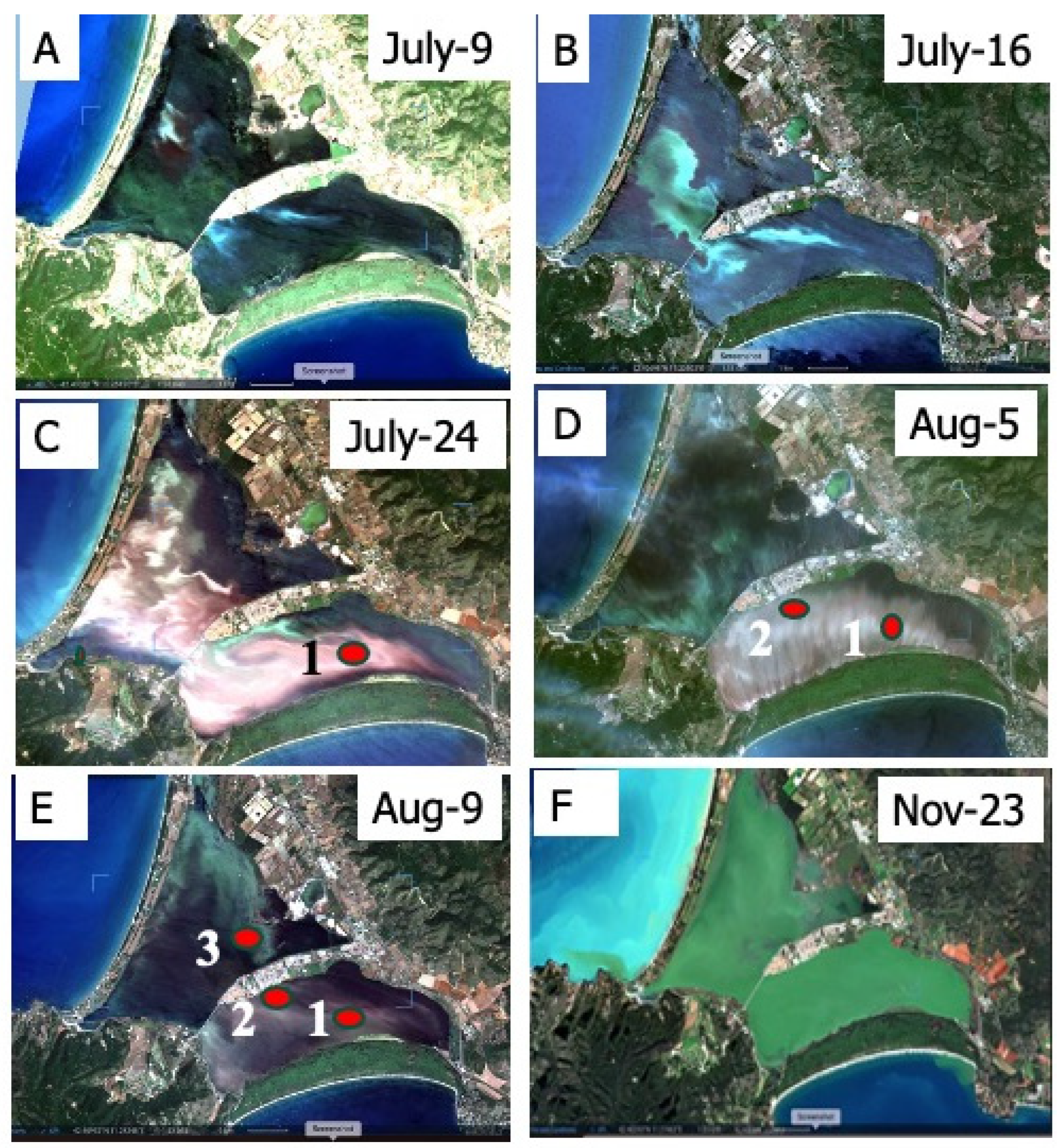

3.4. Dystrophy

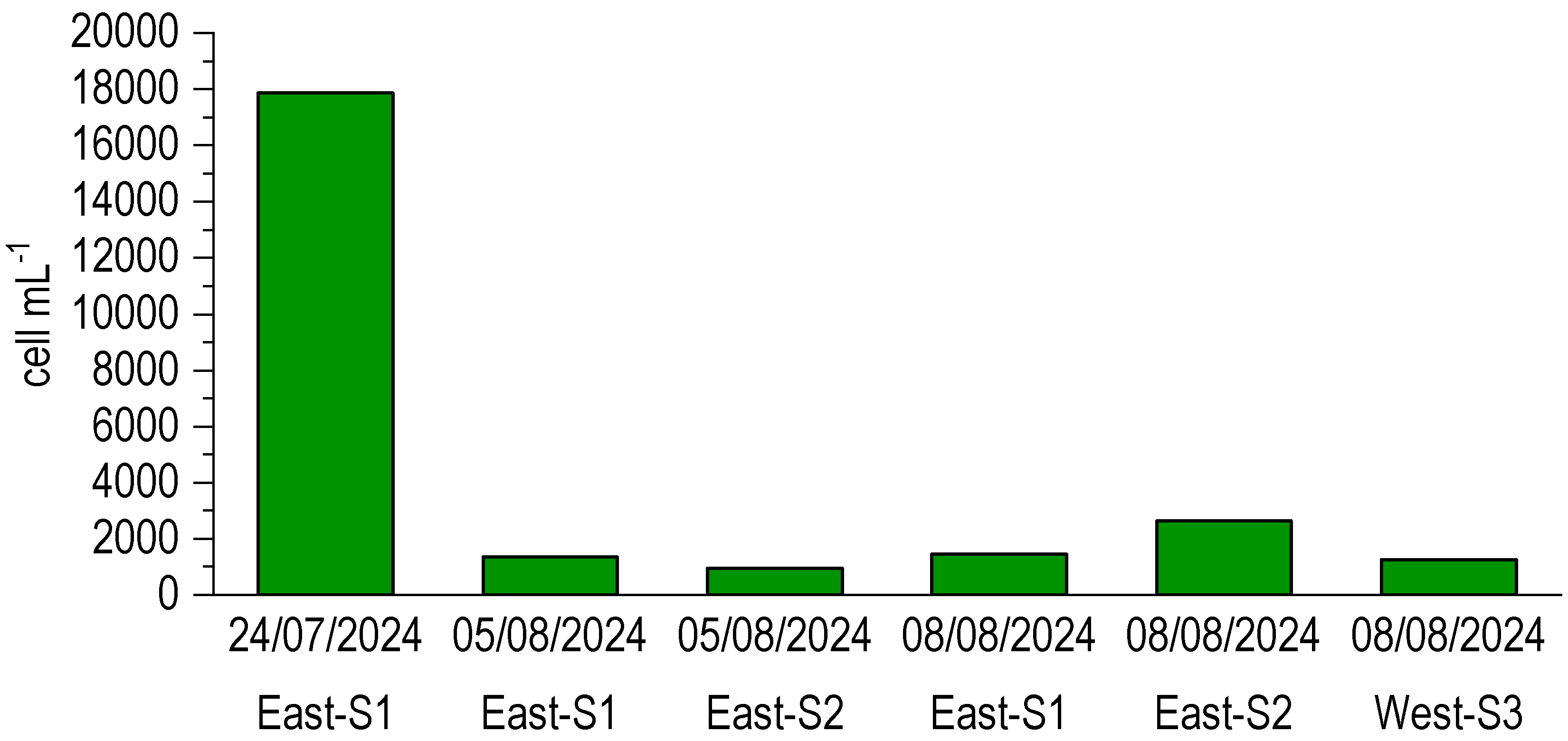

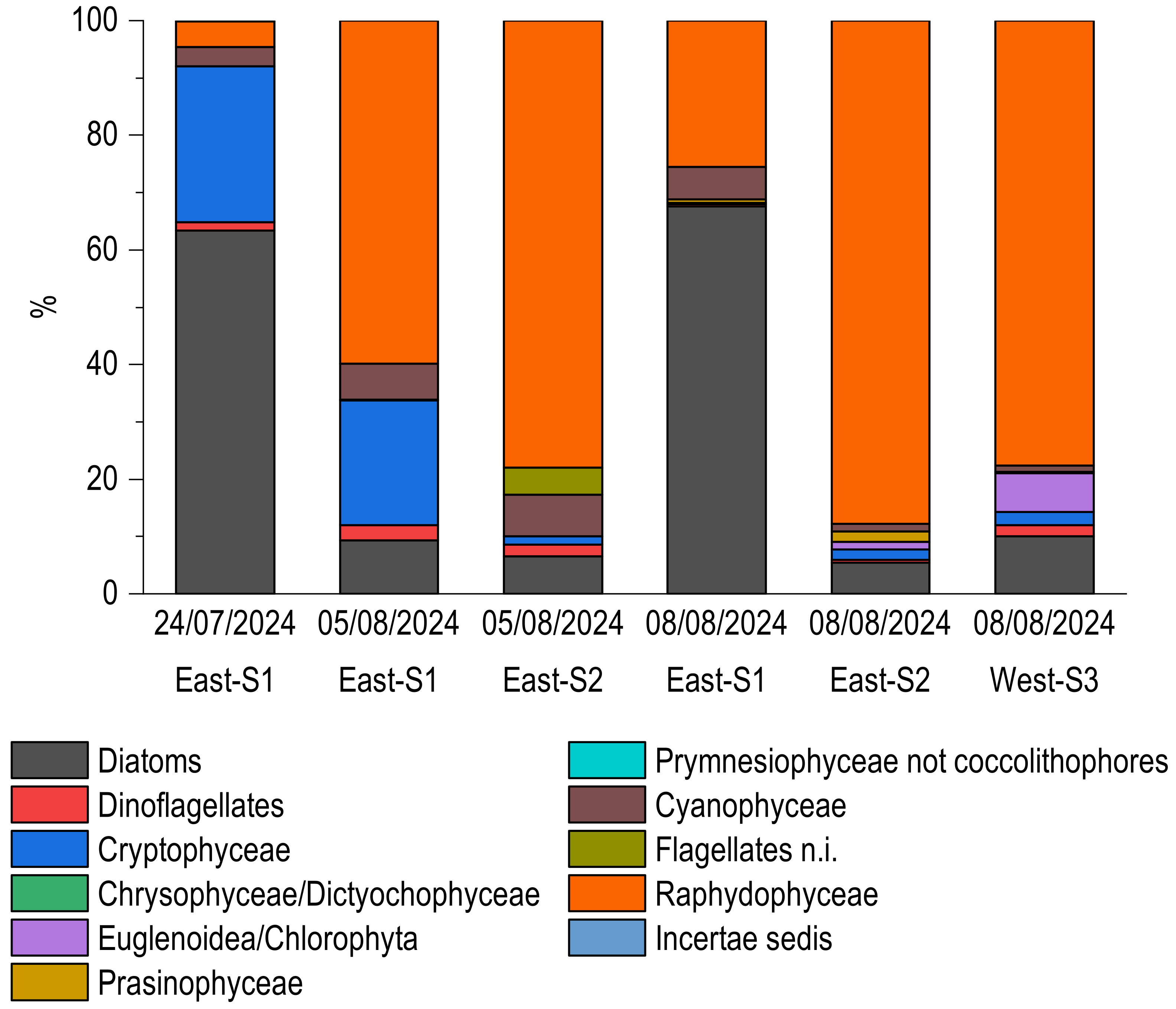

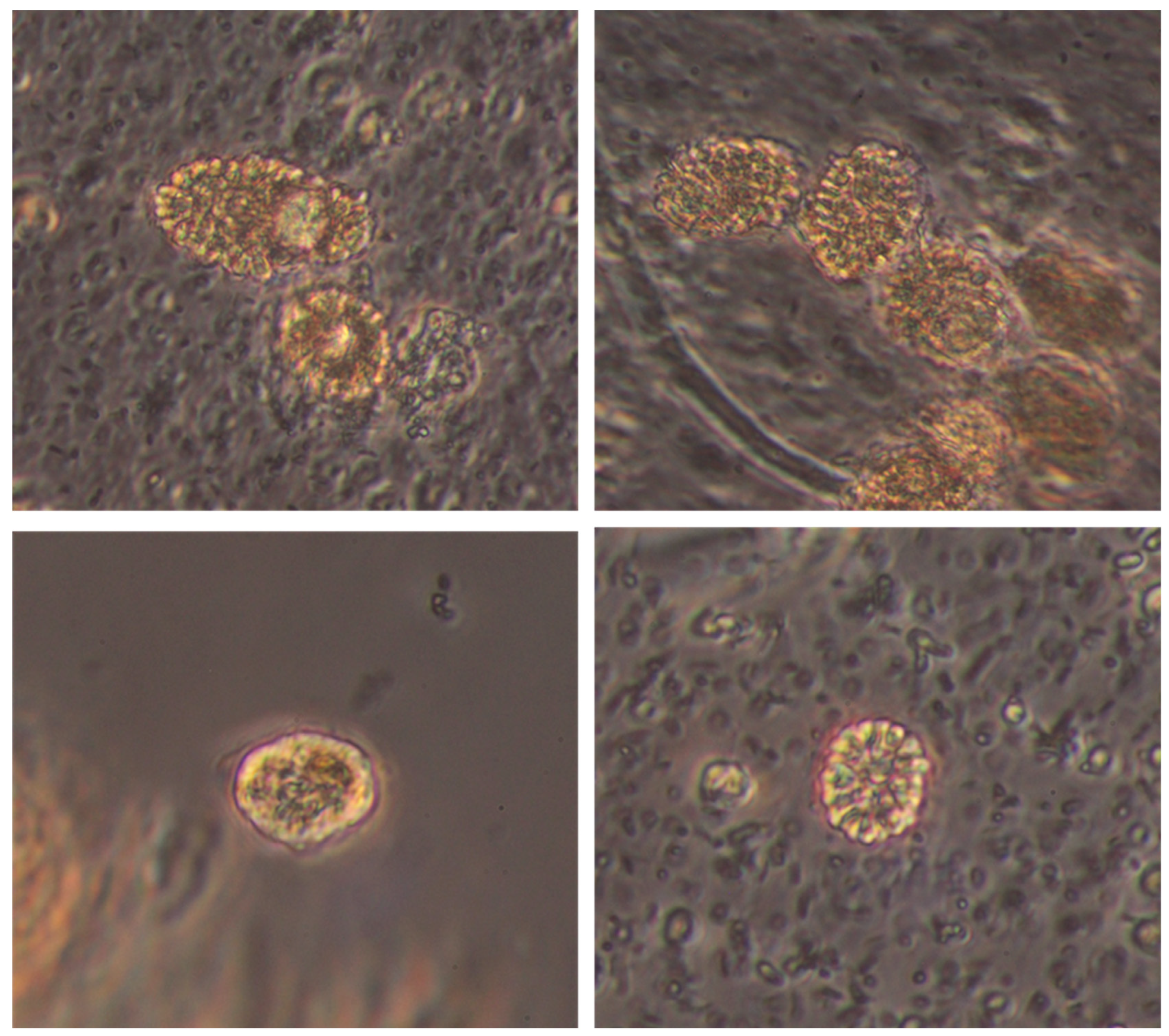

3.5. Microphyte Determinations

4. Discussion

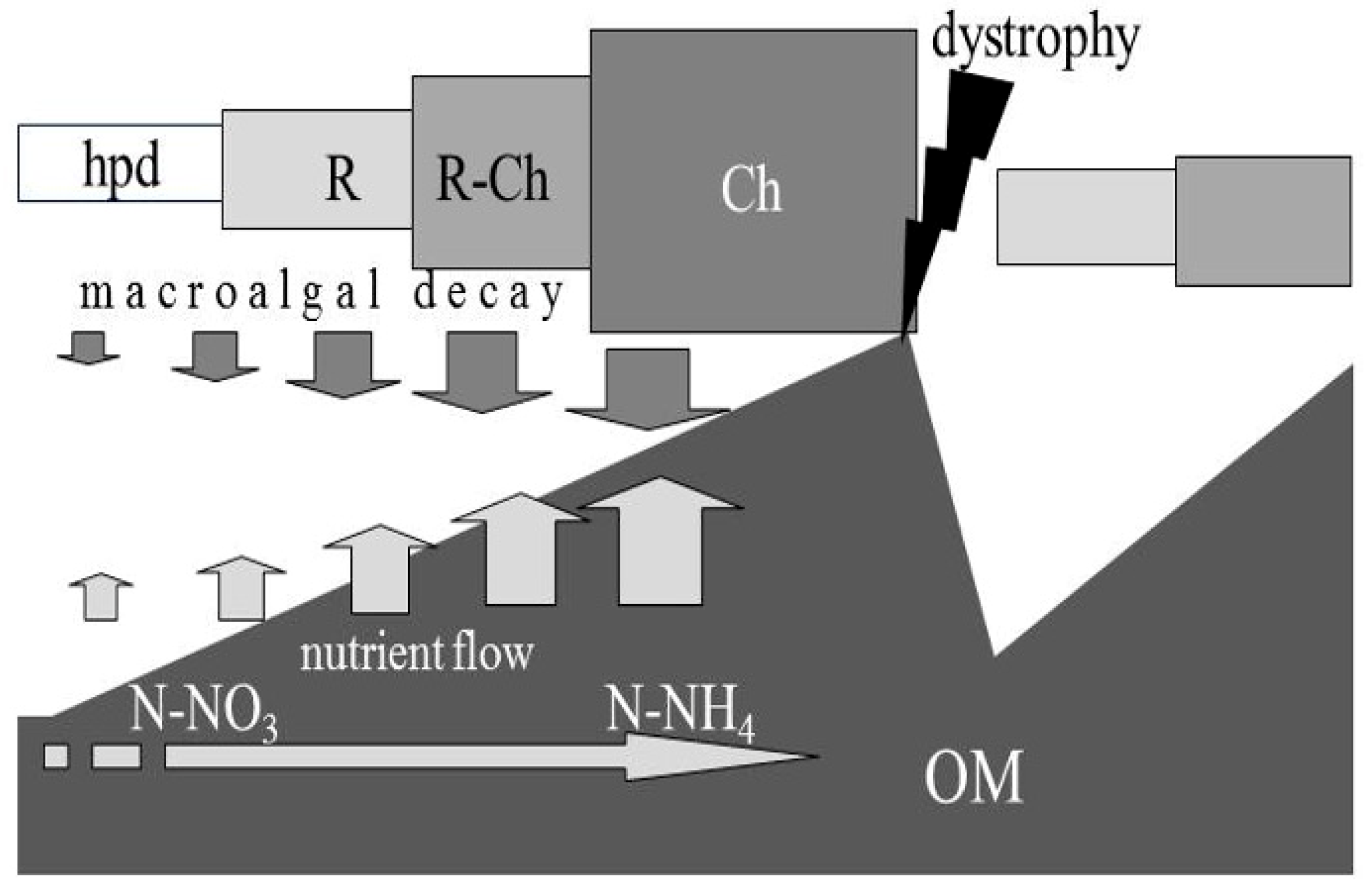

4.1. Macroalgae and Sediment Labile Organic Matter

4.2. Dystrophy Evolution and Microphyte Blooms

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boyer, W.; Howarth, R.W. Chapter 36—Nitrogen Fluxes from Rivers to the Coastal Oceans. In Nitrogen in the Marine Environment; Capone, D.G., Bronk, D.A., Mulholland, M.R., Carpenter, E.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.H.; Schluter, L.; Ærtebjerg, G. Coastal eutrophication: Recent developments in definitions and implications for monitoring strategies. J. Plankton Res. 2006, 28, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégori, G.J.; Dugenne, M.; Thyssen, M.; Garcia, N.; Nicolas, M.; Bernard, G. Monitoring of a Potential Harmful Algal Species in the Barre Lagoon by Automated in Situ Flow Cytometry. In Marine Productivity: Perturbations and Resilience of Socio-Ecosystems; Ceccardi, H.J., Hénocque, Y., Koike, Y., Komatsu, T., Stora, G., Tusseau-Vuillemin, M.-H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hauxwell, J.; Valiela, I. Effects of nutrient loading on shallow seagrass-dominated coastal systems: Patterns and processes. In Estuarine Nutrient Cycling: The Influence of Primary Producers; Nielsen, S.L., Banta, G.T., Pedersen, M.F., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier, R.H.; Morand, P.; Finkl, C.W.; Thys, A. Green tides on the Brittany coasts. Environ. Res. Eng Manag. 2007, 3, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Pang, S.; Chopin, T.; Gao, S.; Shan, T.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. Understanding the recurrent large-scale green tide in the Yellow Sea: Temporal and spatial correlations between multiple geographical, aquacultural and biological factors. Mar. Environ. Res. 2013, 83, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Quintino, V. The estuarine quality paradox, environmental homeostasis and the difficulty of detecting anthropogenic stress in naturally stressed areas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 54, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M. Submerged aquatic vegetation in relation to different nutrient regimes. Ophelia 1995, 41, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Gennaro, P.; Renzi, M.; Persia, E.; Porrello, S. Spread of Alsidium corallinum C. Ag. in a Tyrrhenian eutrophic lagoon dominated by opportunistic macroalgae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2699–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlathery, K. Macroalgal blooms contribute to the decline in seagrasses in nutrient-enriched coastal waters. J. Phycol. 2001, 37, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.; Jørgensen, B.B.; LaRowe, D.E.; Middelburg, J.J.; Pancost, R.D.; Regnier, P. Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: A review and synthesis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2013, 123, 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnars, A.; Blomqvist, S. Phosphate exchange across the sediment-water interface when shifting from anoxic to oxic conditions: An experimental comparison of freshwater and brackish-marine systems. Biogeochemistry 1997, 37, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozan, T.F.; Taillefert, M.; Trouwborst, R.E.; Glazer, B.T.; Ma, S.; Herszage, J.; Valdes, L.M.; Price, K.S.; Luther, G.W., III. Iron-sulphur-phosphorus cycling in the sediments of a shallow coastal bay: Implications for sediment nutrients release and benthic macroalgal blooms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2002, 47, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, P.N.; Klinkhammer, G.P.; Bender, M.L.; Luedtke, N.A.; Heath, G.R.; Cullen, D.; Dauphin, P.; Hammond, D.; Hartman, B.; Maynard, V. Early oxidation of organic-matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial atlantic-suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1979, 43, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikaew, P.; Sompongchaiyakul, P. Acid volatile sulphide estimation using spatial sediment covariates in the Eastern Upper Gulf of Thailand: Multiple geostatistical approaches. Oceanologia 2018, 60, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, A.; Jorgensen, B.B. Biogeochemistry of pyrite and iron sulfide oxidation in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochi. Acta 2002, 66, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenchel, T.; Jorgensen, B.B. Detritus food chains of aquatic ecosystems: The role of bacteria. In Advances in Microbial Ecology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1977; Volume 1, 58p. [Google Scholar]

- Berner, R.A. Sedimentary pyrite formation: An uptdate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisler, A.; de Beer, D.; Lichtschlag, A.; Lavik, G.; Boetius, A.; Jorgensen, B.B. Biological and chemical sulfide oxidation in a Beggiatoa inhabited marine sediment. ISME J. 2007, 1, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, G.; Azzoni, R.; Viaroli, P. A rapid assessment of the sedimentary buffering capacity towards free sulphides. Hydrobiologia 2008, 611, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M. Vegetation structure of lagoon environments as a result of sediment biogeochemical dynamics and organic matter load: A review. In Macrophytes. Biodiversity, Role in Aquatic Ecosystems and Management Strategies; Capello, R., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2014; Chapter 3; pp. 15–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, M.; Renzi, M.; Nesti, U.; Gennaro, P.; Persia, P.; Porrello, S. Vegetation cyclic shift in eutrophic lagoon. Assessment of dystrophic risk indices based on standing crop evaluations. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 13, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, A.; Dell’Anno, A.; Danovaro, R.; Marini, E.; Sarà, G.; Fabiano, M. Enzymatically hydrolysable protein and carbohydrate sedimentary pools as indicators of the trophic state of “detritus sink” systems: A case study in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Estuaries 2003, 26, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolomio, C.; Lenzi, M. Eaux colorees dans les lagunes d’Orbetello et de Burano (Mer Tyrrhenienne du Nord) de 1986 à 1989. Vie Milieu/Life Environ. 1996, 46, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, M.; Persiano, M.; Gennaro, P.; Rubegni, F. Wind Mitigating Action on Effects of Eutrophication in Coastal Eutrophic Water Bodies. Int. J. Mar. Sci. Ocean Technol. 2016, 3, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, L.; Adamson, J.; Suzuki, T.; Briggs, L.; Garthwaite, I. Toxic marine epiphytic dinoflagellates, Ostreopsis siamensis and Coolia monotis (Dinophyceae), in New Zealand. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2000, 34, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, N.; Szelag-Wasielewska, E. Toxic Picoplanktonic Cyanobacteria. Review. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1497–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Palmieri, R.; Porrello, S. Restoration of the eutrophic Orbetello lagoon (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy): Water quality management. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Gennaro, P.; Franchi, E.; Marsili, L. Assessment of fish-farms wastewater synergistic impact on a Mediterranean non-tidal lagoon. J. Aquac. Fisheries 2019, 3, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DICEA, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Research Activity for the Mitigation of Eutrophic Processes in the Orbetello Lagoon: Study on the Estimation of the Nutrient Balance and on the Numerical Model of the Hydrodynamic Circulation; University of Florence: Firenze, Italy, 2019; 264p. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzi, M.; Renzi, M. Effects of artificial disturbance on quantity and biochemical composition of organic matter in sediments of a coastal lagoon. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2011, 402, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, P.S. An Assessment of the Contribution of Terrestrial Organic Matter to Total Organic Matter in Sediments in Scottish Sea Lochs. Ph.D. Thesis, UHI Millenium Institute, Inverness, UK, 2005; 350p. [Google Scholar]

- Utermöhl, H. Zur Vervollkommnung der quantitativen Phytoplankton-Methodik: Mit 1 Tabelle und 15 abbildungen im Text und auf 1 Tafel. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. Mitteilungen 1958, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, A.; Totti, C.; Sarno, D.; Cabrini, M.; Caroppo, C.; Giacobbe, M.; Lugliè, A.; Nuccio, C.; Socal, G. Fitoplancton: Metodiche di analisi quali-quantitativa. In Metodologie di Studio del Plancton Marino; ISPRA SIBM: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, M.; Cianchi, F. Summer Dystrophic Criticalities of Non-Tidal Lagoons: The Case Study of a Mediterranean Lagoon. Diversity 2022, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M. Cacciatori di Solfaie Ambienti Lagunari Atidali Eutrofici e Meccaniche Distrofiche; PandioN: Roma, Italy, 2019; 116p. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, M.; Leporatti Persiano, M.; D’Agostino, A. Growth tests of Gongolaria barbata (Ochrophyta Sargassaceae), a native species producing pleustophitic blooms in a hypertrophic Mediterranean lagoon. J. Aquac. Mar. Biol. 2024, 13, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccio, C.; Melillo, C.; Massi, L.; Innamorati, M. Phytoplankton abundance, community structure and diversity in the eutrophicated Orbetello lagoon (Tuscany) from 1995 to 2001. Oceanol. Acta 2003, 26, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souchou, P.; Gasc, A.; Collos, Y.; Vaquer, A.; Tournier, H.; Bibent, B.; Desious-Paolin, J.-M. Biogeochimical aspects of bottom anoxia in a Mediterranean lagoon (Thau, France). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998, 164, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J.; Wei, Q.; Fu, F.; Shao, H. Decomposition of macroalgal blooms influences phosphorus release from sediments and implications for coastal restoration in Swan Lake, Shandong, China. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 60, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorce, C.; Persiano Leporatti, M.; Lenzi, M. Growth and physiological features of Chaetomorpha linum (Müller) Kütz. in high density mats. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 129, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzi, M. Growth Test of 5 Native Opportunistic Species Producing Blooms in a Hypertrophic Mediterranean Lagoon. Prog. Aqua Farming Mar. Biol. 2024, 4, 180043. [Google Scholar]

- Zannella, A.; Simonetti, I.; Lubello, C.; Cappietti, L. Hydrodynamics, transport time scales and water temperature dynamics in heavily anthropized eutrophic coastal lagoon. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 314, 109146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, A.; Dell’Anno, A.; Fabiano, M. Organic matter composition in coastal sediments at Terra Nova Bay (Ross Sea) during summer 1995. Pol. Biol. 2000, 23, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, A.; Dell’Anno, A.; Fabiano, M.; Danovaro, R. Quantity and bioavaillability of sediment organic matte ras signatures of benthic trophic status. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 375, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, A.; Grémare, A.; Escoubeyrou, K.; Amoroux, J.M.; Fiordelmondo, C.; Danovaro, R. Impact of natural (storm) and anthropogenic (trawling) sediment resuspension on particulate organic matter in coastal environments. Cont. Shelf Res. 2005, 25, 2506–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souchu, P.; Abadie, E.; Vercelli, C.; Buestel, D.; Sauvagnargues, J.-C. La Creise Anoxique du Basin de Thau de l’ete 1997. Bilqn Du phenomene et Perspectives; R.INT.DEL/98.04/SETE; IFREMER: Brest, France, 1998; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, A.; Lazure, P.; Souchu, P. Modelisation numerique des crisis anoxiques (malaigues) dand la lagune de Thau (France). Oceanol. Acta 2001, 24 (Suppl. S1), 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamon, P.-Y.; Vercelli, C.; Yves, P.; Lagards, F.; Le Gall, P.; Oheix, J. Les malaïgues de l’ètang de Thau. Tome 2. Descriptgion des malaïgues. Moyens de lute, Recommandations; DRV/RA/RST/2003-01; IFREMER: Brest, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cladas, Y.; Papantoniou, G.; Bekiari, V.; Fragkopoulu, N. Dystrophic crisis event in Papas Lagoon, Araxos Cape, Western Greece in the summer 2012. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2016, 17, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, A. Il fenomeno del lago di sangue nello stagno di Pergusa in Sicilia Alla Metà di Settembre 1932. G. Bot. Ital. 1933, 40, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruti, A. Le condizioni oceanografiche e biologiche del mar Piccolo di Taranto durante l’agosto del 1938. Boll. Pesca Piscic. Idrobiol. 1938, 14, 711–751. [Google Scholar]

- Cvliic, V. Apparition de’eau rouge dans le “Veliko jezero”. Rapp. P. Reun Commn int. Explor. Sci. Mer Mediterr. 1955, 15, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Truper, H.; Genovese, S. Characterization of photosynthetic sulfur bacteria causing red water in lake Faro (Sicily). Hydrobiologia 1968, 47, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caumette, P.; Baleux, B. Etude de eaux rouges dues à la proliferation des bacteries photosyntethetiques sulfo-oxydantes dans l’etang du Prevost, lagune saumatre mediterraneenne. Mar. Biol. 1980, 56, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SC (tww) | Dominances | Dystrophies/Basin | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 40,615 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc | |

| 2019 | 42,079 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc | |

| 2020 | 40,114 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc + Gb | |

| 2021 | 53,382 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc + Gb | |

| 2022 | 27,399 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc + Gb | D2, East |

| 2023 | 49,672 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc + Gb | |

| 2024 | 53,290 | CH > V >> Ac + Sc + Gb | D3, East and West |

| Year | Month | East | West | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Min | T-Mean | T-Max | T-Min | T-Mean | T-Max | ||

| 2013 | July | 24.1 | 29.0 | 32.7 | 24.1 | 29.0 | 29.0 |

| Aug | 25.4 | 28.2 | 30.8 | 25.4 | 28.3 | 28.3 | |

| 2014 | July | 24.3 | 27.2 | 29.6 | 24.3 | 27.3 | 27.3 |

| Aug | 24.3 | 27.4 | 30.7 | 24.3 | 27.4 | 27.4 | |

| 2015 | July | 28.3 | 31.2 | 34.9 | 28.3 | 31.1 | 31.1 |

| Aug | 25.8 | 28.6 | 32.5 | 25.8 | 28.5 | 28.5 | |

| 2016 | July | 21.9 | 28.4 | 33.1 | 21.9 | 28.5 | 28.5 |

| Aug | 21.9 | 27.3 | 30.9 | 21.9 | 27.4 | 27.4 | |

| 2017 | July | 23.8 | 28.3 | 31.7 | 23.8 | 28.4 | 28.4 |

| Aug | 23.5 | 28.1 | 32.5 | 23.5 | 28.1 | 28.1 | |

| 2018 | July | 25.4 | 28.4 | 31.0 | 25.4 | 28.4 | 31.2 |

| Aug | 23.3 | 28.6 | 32.5 | 23.3 | 28.6 | 32.1 | |

| 2019 | July | 23.7 | 28.8 | 32.1 | 23.7 | 28.7 | 32.7 |

| Aug | 25.4 | 28.6 | 31.5 | 25.4 | 28.7 | 31.8 | |

| 2020 | July | 25.2 | 28.3 | 32.2 | 25.2 | 27.3 | 32.0 |

| Aug | 23.7 | 28.3 | 31.1 | 23.7 | 28.2 | 31.2 | |

| 2021 | July | 24.2 | 27.6 | 30.7 | 24.2 | 27.3 | 31.1 |

| Aug | 23.1 | 28.1 | 32.0 | 23.1 | 28.1 | 31.9 | |

| 2022 | July | 24.5 | 29.6 | 33.0 | 24.5 | 29.6 | 32.7 |

| Aug | 24.6 | 28.3 | 32.4 | 24.6 | 28.3 | 31.8 | |

| 2023 | July | 25.7 | 28.7 | 32.0 | 25.7 | 29.8 | 32.7 |

| Aug | 22.6 | 27.8 | 31.1 | 22.6 | 27.6 | 31.1 | |

| 2024 | July | 25.6 | 29.0 | 32.5 | 25.6 | 29.3 | 32.7 |

| Aug | 26.9 | 30.1 | 34.1 | 26.9 | 30.1 | 33.0 |

| 1996 | 2003 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromista | |||

| Heterokontophyta | |||

| Bacillariophyceae | |||

| Chaetoceros spp. | X | X | |

| Chaetoceros neogracile | X | ||

| Chaetoceros simplex | X | X | |

| Chaetoceros compressus | X | ||

| Chaetoceros tenuissimus | X | X | |

| Leptocylindrus danicum | X | ||

| Bacellariophyceae centric undetermined | X | ||

| Proboscia alata | X | ||

| Paralia sulcata | X | ||

| Thalassiosira spp. | X | ||

| Thalassiosira angulata | X | ||

| Thalassiosira delicatula | X | ||

| Rhizosolenia cf. pungens | X | ||

| Rhizosolenia cf. setigera | X | ||

| Rhizosolenia sp. | X | ||

| Amphiprora gigantea var. sulcata | X | ||

| Skeletonema costatum | X | X | |

| Amphiprora spp. | X | ||

| Achnantes | X | ||

| Amphora cymbifera | |||

| Anphora hyalina | X | ||

| Amphora turgida | X | ||

| Amphora laevis | X | ||

| Amphora spp. | X | X | |

| Bacellariophyceae centric undetermined-2 | X | ||

| Asterionellopsis glacialis | X | ||

| Cocconeis scutellum | X | X | |

| Achnanthes brevipes | X | ||

| Cylindrotheca closterium | X | X | X |

| Cocconeis spp. | X | ||

| Diploneis crebro | X | ||

| Diploneis spp. | X | ||

| Bacillaria paxillifera | X | ||

| Bacillariophyceae pennate <20 µm | X | ||

| Bacillariophyceae pennate >20 µm | X | ||

| Pleurosigma sp. | X | X | |

| Pleurosigma affine | X | ||

| Pleurosigma normanii | X | X | |

| Pleurosigma elongatum | X | ||

| Eunotia sp. | X | ||

| Fragilaria spp. | X | ||

| Entomoneis cf. paludosa | X | ||

| Halamphora coffeiformis | X | ||

| Licmophora gracilis | X | ||

| Licmophora flabellata | X | ||

| Licmophora spp. | X | ||

| Navicula spp. | X | X | X |

| Navicula transitans var. derasa | X | ||

| Mastogloia sp. | X | ||

| Nitzschia distans | X | ||

| Nitzschia longissima | X | X | X |

| Nitzschia cf. acicularis | X | ||

| Nitzschia sp. | X | ||

| Grammatophora oceanica | X | X | |

| Striatella unipunctata | X | X | |

| Eutreptiella marina | X | ||

| Melosira juergensi | X | ||

| Grammatophora spp. | |||

| Synedra spp. | X | ||

| Thalassionema spp. | X | ||

| Thalassiothrix sp. | X | ||

| Bacillariophyceae undetermined-3 | X | ||

| Thalassionema nitzschioides | X | ||

| Tryblionella punctata | X | ||

| Dinophyceae | |||

| Amphidinium spp. | X | X | |

| Dinophysis caudata | X | ||

| Dinophysis spp. | X | ||

| Goniaulax scrippsae | X | ||

| Goniaulax spp. | X | ||

| Gymnodiniaceae | X | ||

| Akashiwo sanguinea (Gymnodinium sanguineum) | X | X | |

| Gymnodinium splendens | X | ||

| Gymnodinium sp. ° | X | X | |

| Gymnodiniaceae < 20 µm | X | ||

| Gymnodiniaceae > 20 µm | X | X | |

| Gymnodinium catenatum | X | ||

| Gyrodinium spp. | X | ||

| Heterocapsa sp. | x | ||

| Alexandrium catenella | X | ||

| Alexandrium cf. minutum | X | ||

| Alexandrium ostenfeldii | X | ||

| Alexandrium pseudogonyaulax | X | ||

| Alexandrium spp. | X | ||

| Dinophyceae thecate < 20 µm | X | ||

| Dinophyceae thecate > 20 µm | X | ||

| Oxyteoxum sceptrum | X | ||

| Oxytoxum sp. | X | ||

| Oxytoxum variabile | X | ||

| Prorocentrum dentatum | X | ||

| Prorocentrum gracile | X | ||

| Prorocentrum micans | X | X | |

| Prorocentrum cordatum (P. minimum) | X | ||

| Prorocentrum lima | X | X | |

| Prorocentrum spp. | X | ||

| Prorocentrum triestinum | X | ||

| Coolia monotis *** | X | ||

| Tryblionella compressa °° (Prorocentrum compressum) | X | ||

| Protoperidinium divergens | X | ||

| Pentapharsodinium tyrrhenicum | X | ||

| Blixaea quinquecornis (Protoperidinium quinquecorne) | X | X | |

| Protoperidinium spp. | X | X | |

| Scrippsiella sp. | X | ||

| Dinophyceae naked | X | ||

| Dinophyceae thecate | X | ||

| Cryptophyceae spp. ** | X | X | X |

| Alisphaera ordinata | X | ||

| Paulinella sp. | X | ||

| Calicomonas sp. | X | ||

| Syracosphaera mediterranea (Coronosphaera mediterranea) | X | ||

| Syracosphaera pulchra | X | ||

| Gephyrocapsa huxleyi (Emiliania huxleyi) | X | ||

| undetermined flagellates <10 mm | X | ||

| undetermined flagellates <20 mm | X | ||

| Prymnesiophycidae | |||

| Phaeocystis sp. | X | ||

| Dictyochophyceae | |||

| Apedinella radians (A. spinifera) | X | X | |

| Raphidophyceae | |||

| Chattonella subsalsa | X | ||

| Fibrocapsa japonica | X | ||

| Heterosigma akashiwo | X | ||

| Protozoa | |||

| Euglenoidea | |||

| Euglena acus | X | ||

| Euglena gasterosteus | X | ||

| Euglena caudata | X | ||

| Euglena pascheri * | X | ||

| Euglena mutabilis | X | ||

| Euglena sp. | X | ||

| Euglena acusformis | X | ||

| Eutreptia sp. | X | ||

| Eutreptia viridis | X | ||

| Eutreptia lanowi | X | ||

| Eutreptiella sp. | X | ||

| Eutreptiella marina | X | ||

| Eutreptiella braarudii | X | ||

| Discosea | |||

| Vannella simplex | X | ||

| Chlorophyta Prasinophyceae | |||

| Pyramimonas spp. | X | ||

| Chlorodendraceae | |||

| Tetraselmis sp. | X | ||

| Cyanobacteria | |||

| Chroococcus dispersus | |||

| Phormidium fragile | X | ||

| Phormidium sp. | |||

| Spirulina sp. | X | ||

| Spirulina subtilissima | |||

| Lyngbya martensiana | |||

| Lyngbya semiplena | |||

| Oscillatoria margaritifera | |||

| Oscillatoria semplicissima | |||

| Schizothrix minuta | |||

| Calothrix confervicola | |||

| Mixoderma goetzii | |||

| Chroococcus dispersus | |||

| Chroococcus limneticus | |||

| Chroococcus membranimus | |||

| Chroococcus turgidus | |||

| Xenococcus acervatus | |||

| Xenococcus cladophore | |||

| Xenococcus kerneri | |||

| Hyella caespitosa | |||

| Merismopedia sp. | X | ||

| Planktolyngbya contorta | X | ||

| Planktothrix sp. | X | ||

| Gloeocapsa sp. | X | ||

| Cyanophyceae undetermined | X | ||

| N. Taxa | 34 | 73 | 59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polonelli, F.; Leporatti Persiano, M.; Melillo, C.; Lenzi, M. Evolution of a Dystrophic Crisis in a Non-Tidal Lagoon Through Microphyte Blooms. Phycology 2025, 5, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040078

Polonelli F, Leporatti Persiano M, Melillo C, Lenzi M. Evolution of a Dystrophic Crisis in a Non-Tidal Lagoon Through Microphyte Blooms. Phycology. 2025; 5(4):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040078

Chicago/Turabian StylePolonelli, Francesca, Marco Leporatti Persiano, Chiara Melillo, and Mauro Lenzi. 2025. "Evolution of a Dystrophic Crisis in a Non-Tidal Lagoon Through Microphyte Blooms" Phycology 5, no. 4: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040078

APA StylePolonelli, F., Leporatti Persiano, M., Melillo, C., & Lenzi, M. (2025). Evolution of a Dystrophic Crisis in a Non-Tidal Lagoon Through Microphyte Blooms. Phycology, 5(4), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040078