1. Introduction

Supplementation of algae in poultry feed has gained interest due to the presence of antioxidative, immunostimulatory and anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds that could increase poultry health and furthermore improve meat and egg quality due to the presence of poly-unsaturated fatty acids, amino acids and pigments [

1,

2]. Microalgae such as

Chlorella vulgaris and

Spirulina (Arthrospira) platensis therefore show potential as a sustainable replacements for antibiotic growth promotors. Also, macroalgae (seaweed, e.g.,

Ulva spp.) can have beneficial effects on poultry health. Furthermore, microalgae (particularly

Spirulina sp. and

Chlorella sp.) are rich in protein and thus show potential as a source of protein in poultry feed [

3].

In recent years consumer behavior has tended toward increasing awareness of the environmental impact of food choices; however, this change is often limited to a niche group, including consumer segments comprising people concerned about either the environment or their health [

4]. As microalgae in broiler diets can affect the color of chicken meat (e.g., more yellow), it is important to assess how this may affect consumer willingness to purchase this meat. The color effect is highly dependent on the inclusion rate of microalgae in poultry feed [

5]. Furthermore, meat color preferences are regionally and culturally dependent [

6].

Only a limited number of studies have been published on consumer perception of algae-fed chicken meat. More research has been performed on consumer opinions regarding the consumption of micro- and macroalgae in the form of either feed supplements or as ingredients in food products [

4,

7,

8,

9]. In Flanders (Belgium), the present study was the first assessment of public perception of consuming chicken meat from algae-fed chickens.

In the present study, consumers were asked about their willingness to buy algae-fed chicken meat and were informed that this meat could appear more yellow than conventional chicken meat. Several questions were included to assess their knowledge of algae and algae products and their motivations to buy or eat algae, meat or algae-fed chicken meat. Barriers to the acceptance of algae-fed chicken meat were evaluated, i.e., the color of the meat, the unfamiliarity with algae or food neophobia. Questions on the importance of labeling and the influence of price were also included. The population of Flanders was approximated as closely as possible by covering different groups of age, gender, degree, income, place of residence and dietary lifestyle preferences (omnivore, flexitarian, vegetarian, vegan or pescatarian). This way, the study can provide group-specific recommendations and highlight the importance of differentiated products on the market.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hypothesis Model

A structured hypothesis model was made when compiling the information to be collected in the questionnaire (

Figure 1). First, demographic data, habits and beliefs of the respondents were evaluated. Second, consumers were asked about their current algae and meat consumption behavior (status quo) and furthermore about what they find important when considering purchasing these products (drivers). Then, questions were asked about their perception of the use of algae in chicken feed (main research question), and the last section assessed their reflections on certain obstacles/opportunities that come with the consumption of algae-fed chicken meat.

2.2. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The research was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Social Science and Humanities (comESSH) of Flanders Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (ILVO) with ethics clearance number ComESSH_2024_11 according to the Code of Ethics for Scientific Research in Belgium. Respondents were first required to sign a comprehensive informed consent form before proceeding with the questionnaire. The informed consent included information on the project and goal of the survey, consent and refusal, benefits, risks, costs, confidentiality and data storage and protection. After completing the survey, participants were asked to agree or disagree with the following statements: ‘I have read and understood the “Informed Consent.” I am aware of the nature of the research study, its purpose, duration, and what is expected of me’, ‘I agree to participate in the research study’, ‘I understand that participation in the study is voluntary and that I can withdraw at any time’, and ‘I consent to the collection, processing, and use of the data within the framework of the scientific research as described in the “Informed Consent” for participants’.

2.3. Questionnaire and Scaling

The questionnaire consisted of 18 main questions, some of which were divided into sub-questions. The survey first collected demographic data (age, gender, degree, income, place of residence) and dietary lifestyle preferences (omnivore, flexitarian, vegetarian, vegan or pescatarian). Secondly, respondents were asked how often they buy chicken meat. In case ‘never’ was indicated, the survey ended. The next question probed the consumers’ openness to new food products using a standardized food neophobia attribute scale with questions such as ‘

I’m afraid to eat things I’ve never eaten before’ [

10]. Participants were asked to answer on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Then the following topics were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale: importance of sustainability in food production and knowledge of microalgae,

Chlorella,

Spirulina and macroalgae (seaweed). The second part of the survey first presented the following statement to ensure that participants all shared the same background information: ‘

Microalgae are microscopic algae that live in freshwater or saltwater. They naturally have a high protein content, and some species (including Chlorella and Spirulina) are approved for consumption by humans and animals’. The questionnaire continued with questions about the following topics: importance of different attributes regarding the consumption of algae, importance of different attributes regarding the purchase of chicken meat, knowledge of potential effects of including algae in chicken feed, importance of labeling feed ingredients on chicken meat packaging and the importance of different attributes when considering the purchase of the meat of algae-fed chickens. Prior to the last question, the following information was provided: ‘

Chicken meat from algae-fed chickens may have a slightly more yellow color than the conventional chicken meat we know’. The questionnaire then gauged the respondent’s willingness to buy chicken meat that appears more yellow than conventional chicken meat, as well as the respondent’s willingness to pay a higher price for algae-fed chicken. The entire questionnaire can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Data Collection

The online questionnaire, compiled in Qualtrics, was disseminated via LinkedIn, Facebook and personal communication via email and orally. The questionnaire was initially distributed via the authors’ professional and personal social media networks (e.g., LinkedIn connections and Facebook friends) in several waves on a weekly basis. It was also shared within other people’s networks, creating a snowball effect. The questionnaire was open for one month between January and February 2025, with the aim of reaching at least 200 representative respondents in Flanders. The raw dataset (n = 320) was cleaned by removing responses from participants who did not complete the whole survey or who responded incorrectly to the validation question. The dataset was also checked for ‘speeders’ (i.e., participants who completed the survey in a remarkably short time). The median response time was 473 s. As the fastest respondent completed the survey in 180 s, no speeders were removed from the dataset. Only responses from people living in the region of Flanders were retained. In total, 23 respondents who stated that they never buy chicken meat were removed from the main dataset. After data clean-up, 275 responses were retained and used for further data analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R version 4.1.2 for Windows [

11]. Linear regression models were built using forward model selection. Variables were retained when their significance was

p < 0.05. Other tested variables with

p > 0.05 were not added in the models. Multicollinearity of the variables was tested using the variance inflation factor (VIF) test. Income was correlated with academic degree and age; thus, this variable was removed from the analysis. Estimates (β) and standard error (SE) are given in the results section.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

Demographic data (age, gender, education and income) were collected (

Table 1). Of the whole dataset (

n = 298), 67.9% indicated that they were omnivorous, and 32.1% indicated that they follow an alternative (i.e., vegetarian, vegan, flexitarian or pescatarian) diet. Of the dataset that retained for data analysis (

n = 275, excluding people that never buy chicken meat), 73.6% were omnivorous, and 26.4% follow an alternative diet.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.2.1. Knowledge About Algae

Figure 2 shows the respondents’ knowledge about algae. In total, 51.3% indicated that they had never heard of

Chlorella, and 40.3% had never heard of

Spirulina. Macroalgae (seaweed) were the most known; only 3.3% had never heard of them. In total, 69.6% had already tasted macroalgae (seaweed), whereas only 11.4% and 24.6% had tasted

Chlorella and

Spirulina, respectively.

3.2.2. Motivations to Eat Algae

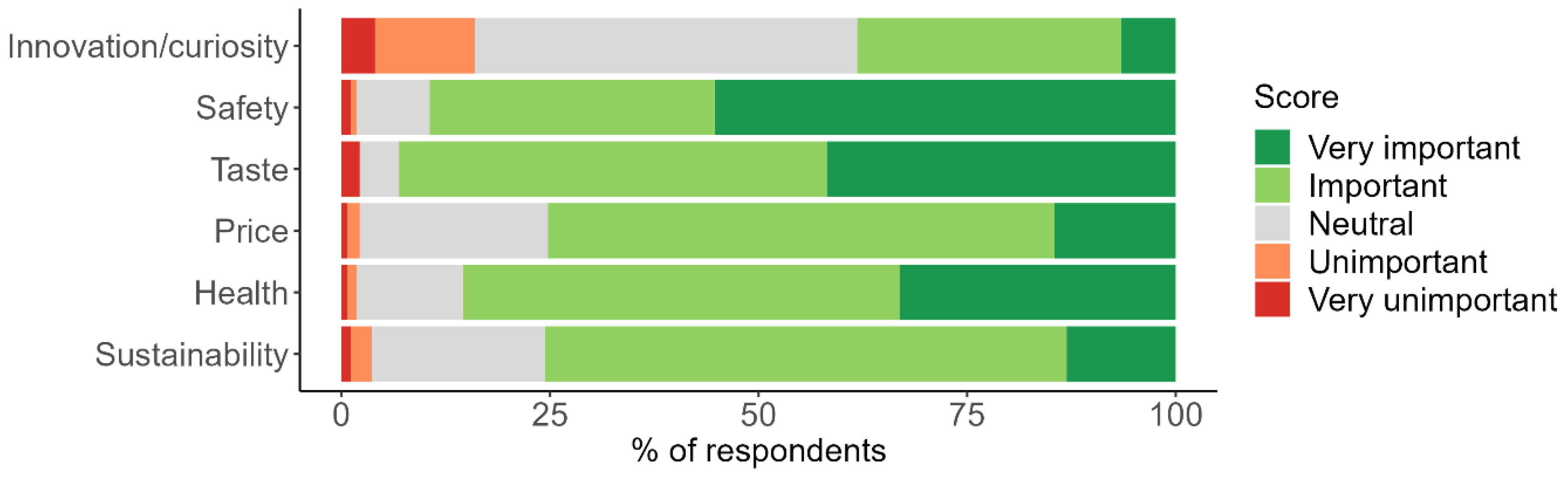

Figure 3 shows the most important factors when eating algae. These are taste, safety and health, with 93.1%, 89.3% and 85.4% indicating ‘important’ or ‘very important’, respectively. Innovation and curiosity appeared to be the least important factor, with 16.1% indicating ‘unimportant’ or ‘very unimportant’ and 45.4% indicating ‘neutral’.

3.2.3. Motivations to Purchase Chicken Meat

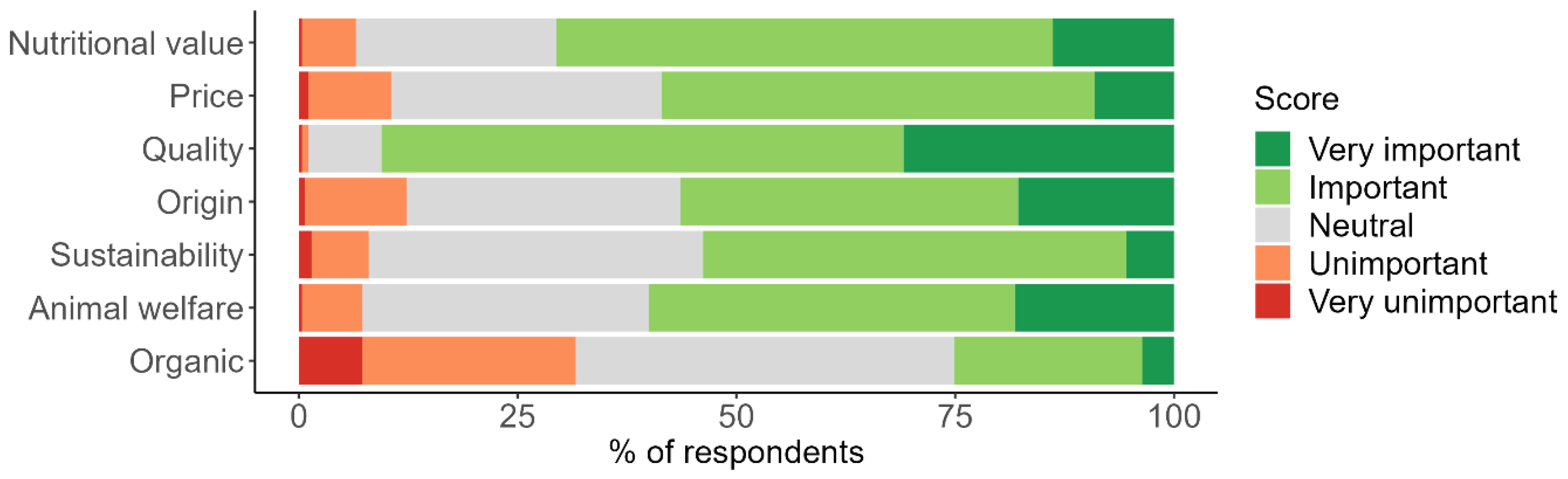

Figure 4 shows the factors influencing the respondents’ motivation to buy chicken meat. Meat quality seemed to be the most important factor, with 90.5% indicating ‘important’ or ‘very important’. Whether the chicken meat was produced in an organic farming system appeared to be of least importance, with only 25.3% indicating ‘important’ or ‘very important’.

3.2.4. Knowledge About the Benefits of Algae in Chicken Feed

Figure 5 shows the knowledge of potential benefits of algae in chicken feed. In total, 61.7% indicated that they expect algae inclusion to increase sustainability of broiler production. For the other benefits, ‘I do not know’ is the most chosen answer (approximately 40% for each question). For taste, only 12.5% of the respondents indicated that they think this would be affected by the use of algae in chicken feed.

3.2.5. Labeling of Algae-Fed Chicken Meat

Figure 6 shows the opinion of the respondents on the use of labeling of chicken meat when algae are used in the feed. In total, 72.5% indicated they would buy chicken meat that has an ‘algae-fed’ label. Only 12.5% disagreed with the statement regarding importance of mentioning feed ingredients on the packaging of chicken meat. When asked about the importance of the label ‘algae-fed’, 19.6% stated that this has little importance for them.

3.2.6. Motivations to Buy Algae-Fed Chicken Meat

Figure 7 show the factors that can motivate consumers to buy algae-fed chicken meat. All variables were approximately of equal importance to the respondent, with around 75% indicating ‘important’ and ‘very important’.

3.3. Willingness to Buy Algae-Fed Chicken Meat

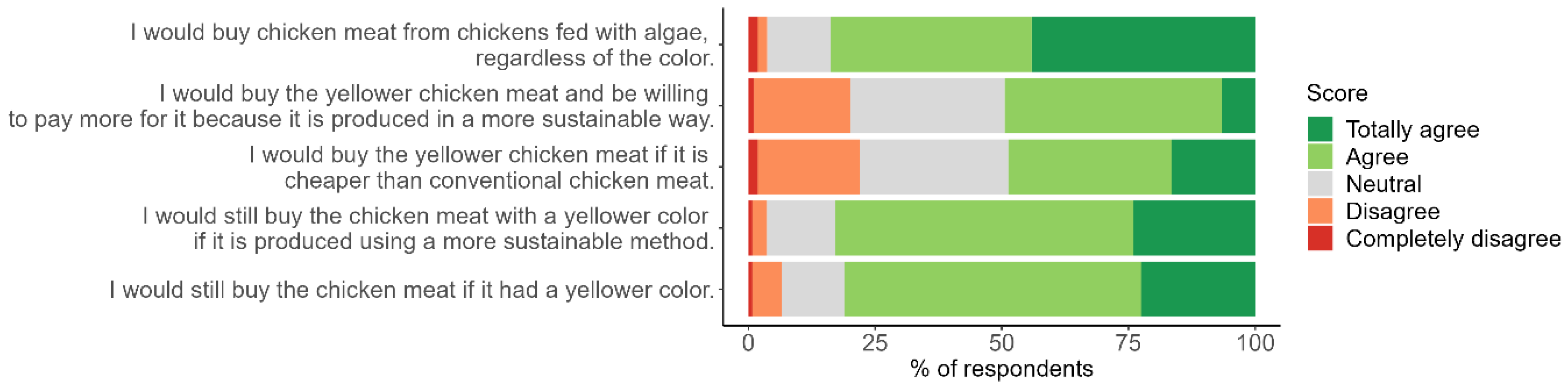

Figure 8 shows the willingness of the respondents to buy algae-fed chicken meat. Color appeared unimportant, with 80.9% indicating that they would still buy chicken meat with a yellower color. This percentage was similar (82.8%) if broiler production would be more sustainable. In total, 83.7% indicated they would buy algae-fed chicken meat, regardless of the color. Remarkably, 48.3% indicated they would buy yellower chicken meat if it was cheaper than conventional meat. Similarly, 49.8% indicated a willingness to pay more if the yellower meat is related to a more sustainable production.

Table 2 shows the variables that influence the responses related to the willingness to buy algae-fed chicken meat. Question (Q) 1, ‘

I would still buy the chicken meat if it had a yellower color’, was mainly influenced by sustainability beliefs and degree. People with a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree or higher scored higher than ‘high school degree or lower’ (

p = 0.007 and 0.001, respectively).

Q2, ‘I would still buy the chicken meat with a yellower color if it is produced using a more sustainable method’, was influenced by the same variables as Q1. Sustainability beliefs had a significant impact on this statement (p < 0.001). Master’s degree or higher scored higher compared to a high school degree or lower (p = 0.006).

Q3, ‘I would buy the yellower chicken meat if it is cheaper than conventional chicken meat’, was mainly influenced by age. In comparison to the 18–30 age group, older age groups scored increasingly lower.

Q4, ‘I would buy the yellower chicken meat and be willing to pay more for it because it is produced in a more sustainable way’, was influenced by sustainability beliefs (p < 0.001). All age groups above 30 scored significantly higher than the baseline group (18–30). Female respondents scored 0.20 ± 0.10 (p = 0.047) points higher compared to male respondents.

Q5: ‘I would buy chicken meat from chickens fed with algae, regardless of the color’ was influenced by sustainability beliefs (p < 0.001), knowledge of algae (p = 0.002) and degree. Bachelor’s degree and master’s degree or higher scored higher than high school degree or lower (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Coefficient estimates from the linear regression models explaining the willingness to buy algae-fed chicken meat (Q1 to Q5).

Table 2.

Coefficient estimates from the linear regression models explaining the willingness to buy algae-fed chicken meat (Q1 to Q5).

| Variable | Β | SE | p-Value |

|---|

| Q1: I would still buy the chicken meat if it had a yellower color. |

| Sustainability | 0.42 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Bachelor’s | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.007 |

| Master’s or higher | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.001 |

| Q2: I would still buy the chicken meat with a yellower color if it is produced using a more sustainable method. |

| Sustainability | 0.55 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Bachelor’s | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.233 |

| Master’s or higher | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.006 |

| Q3: I would buy the yellower chicken meat if it is cheaper than conventional chicken meat. |

| Age: 30–40 | −0.37 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Age: 40–50 | −0.50 | 0.18 | 0.045 |

| Age: 50–60 | −0.72 | 0.18 | 0.006 |

| Age: 60+ | −0.99 | 0.22 | 0.001 |

| Q4: I would buy the yellower chicken meat and be willing to pay more for it because it is produced in a more sustainable way. |

| Sustainability | 0.66 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Age: 30–40 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.018 |

| Age: 40–50 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.116 |

| Age: 50–60 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.006 |

| Age: 60+ | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.013 |

| Female | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.047 |

| Q5: I would buy chicken meat from chickens fed with algae, regardless of the color. |

| Sustainability | 0.28 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Knowledge | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Bachelor’s | 0.53 | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Master’s or higher | 0.59 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

Baseline for degree is ‘high school or lower’, baseline for age is ‘18–30’, and baseline for gender is ‘male’. ‘Sustainability’ is a scale for three questions from the questionnaire assessing opinion on sustainability (higher is more important). ‘Knowledge’ is a scale for four questions from the questionnaire gauging the knowledge of algae products (higher represents more knowledge). β are the estimates, SE is standard error, p-value with significance level α = 0.05 from the Wald test.

4. Discussion

Microalgae have been studied widely for their potential health benefits in poultry. Several articles reported improvements in the morphology of the intestinal tract (villi and crypts) [

12,

13]. Other studies reported improvements in the antioxidant status of broilers [

14,

15]. Therefore, algae could serve as health-promoting agents. This study aimed to gauge people’s opinion on the use of algae in broiler feed. General knowledge of microalgae and macroalgae appeared to differ greatly. To clarify the term ‘macroalgae’, the word ‘seaweed’ was added (which is indeed more generally known). The terms

Chlorella and

Spirulina were unfamiliar to most consumers. In Belgium, these microalgae are mainly sold as food supplements in specialized stores and are not as commonly known as the seaweed preparations served in restaurants and found in many grocery stores. Another study in Belgium reported similar observations, where 51.9% of the respondents had never heard of foods with microalgae [

4]. A study in Spain by Lafarga et al. (2021) [

16] revealed that 26% of the respondents had never heard of microalgae, in comparison to the 15% in the current study who never heard of it before. In Lafarga et al. (2021), 25% of respondents indicated having heard of both

Chlorella and

Spirulina, while 1.3% had only heard of

Chlorella and 37.6% had only heard of

Spirulina [

16]. This indicates that in that group,

Spirulina is much more known than

Chlorella. In our study of Flanders

Spirulina was also slightly more known than

Chlorella, but the discrepancy was much smaller

The survey results indicated that 80.9% of the study group would buy algae-fed chicken meat if it had a yellower color. Furthermore, 83.7% indicated they would buy algae-fed chicken meat regardless of the color. This indicates that for most people, color would not be a barrier to buy algae-fed chicken meat. However, this survey only asked these questions without showing pictures of the actual breast meat. Therefore, in future studies, choice experiments should be performed. These results are in accordance with the German study of Altmann et al. (2019) [

17], which conducted a choice experiment where three breast fillets were offered to consumers, i.e., one fillet from broilers fed with either

Spirulina, insect meal or conventional soy, respectively. Insect meal shows only a limited impact on the color of the breast meat, while microalgae inclusion can affect the color. When no information was given about the animal diets, consumers showed equal appreciation for all three samples. However, when information was provided about the sustainability of these feed ingredients, environmentally-concerned people preferred the use of sustainable feed ingredients such as

Spirulina or insect meal. This indicated the importance of information and labeling. Another German study (Weinrich and Busch, 2021) [

18] found that 45% of the respondents indicated a willingness to buy meat from chickens fed with algae in their diets, which was lower than in the present Flemish study. This may point to cultural or regional differences in preference for color of chicken meat [

6].

Obviously, food safety is an important criteria that influences consumer willingness to eat meat produced using algae in the animal diet. In contrast, innovation or curiosity scored rather low. However, the study of Van der Stricht et al. (2024) [

4] found that consumers showing high willingness to try microalgae saw the algae as innovative ingredients that are rich in vitamins, minerals and fibers. Another study by Meixner et al. (2023) [

19] found that consumers in Austria scored 5.66 and 5.02 out of 7 on novelty and curiosity, respectively.

In the current study, 72.5% of the respondents indicated that they would buy chicken meat labeled as ‘algae-fed’. However, 12.5% of respondents indicated that they do not find labeling of feed ingredients important, and even more people indicated that an ‘algae-fed’ label would not influence their decision to buy a product. A review study by Potter et al. (2021) [

20] revealed that ecolabels can enhance and promote selection, purchase and consumption of sustainable products and that especially logos can help in this. The combination of logos and text appeared to be less effective. The majority of respondents found labeling rather important; therefore, labeling might possibly influence their decision to purchase these products. A study by Pinto da Rosa (2021) [

21] also showed that labeling influences the acceptability of a product. Furthermore, that study showed the importance of animal welfare in the decision of consumers to buy chicken meat.

Nearly half (48.3%) indicated they would buy yellower chicken meat if it were cheaper than conventional meat. This effect was mainly found in the under-30 group, while for the 30+ groups this was less important. Likewise, the older age groups indicated a willingness to pay more for algae-fed chicken meat because it is a more sustainable production method. The study of Van der Stricht et al. (2024) [

4] also indicated that price is an important factor in people’s decision to buy sustainable products.

Sustainability beliefs and educational level appeared to be the most important factors that influence consumer opinions regarding the purchase of algae-fed chicken meat. This is important information for retail, as adding background information (production practices, feed ingredients, potential advantages, etc.) regarding the sustainable production of foods could enhance sales of these products, especially for environmentally concerned consumers. These are important factors for marketing and communication. The heightened interest shown by higher educated consumers might be due to either increased awareness of environmental and climate issues or a higher trust in innovation and technology. Notably, almost 50% of the respondents indicated ‘I do not know’ for the potential benefits algae might have on chicken meat. Therefore, informing consumers about possible advantages might help to inform their perception of these products. Recent studies have indeed shown that sustainability considerations are important for consumers but only when sustainable choices are also related to easy behavior. The carbon footprint should be taken into account when setting prices. Furthermore, labeling should indicate the carbon footprint, which makes it easier to compare with alternatives [

22].

The study showed that it is important to tailor marketing strategies to specific segments of the population. Some respondents consider sustainability important, while others focus primarily on price. The color did not appear to be a major concern. However, these results might differ if a real choice experiment were conducted. A limitation of this study was that it covered only a limited segment of the Flemish population. However, the respondents were fairly well distributed across different demographic categories. The survey was primarily distributed through social media, which may have restricted the participation of certain groups, such as older people.