Snack Attack: Understanding Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Favour and Disfavour for Cyanobacteria (Blue-Green Algae)-Based Crackers

Abstract

1. Introduction

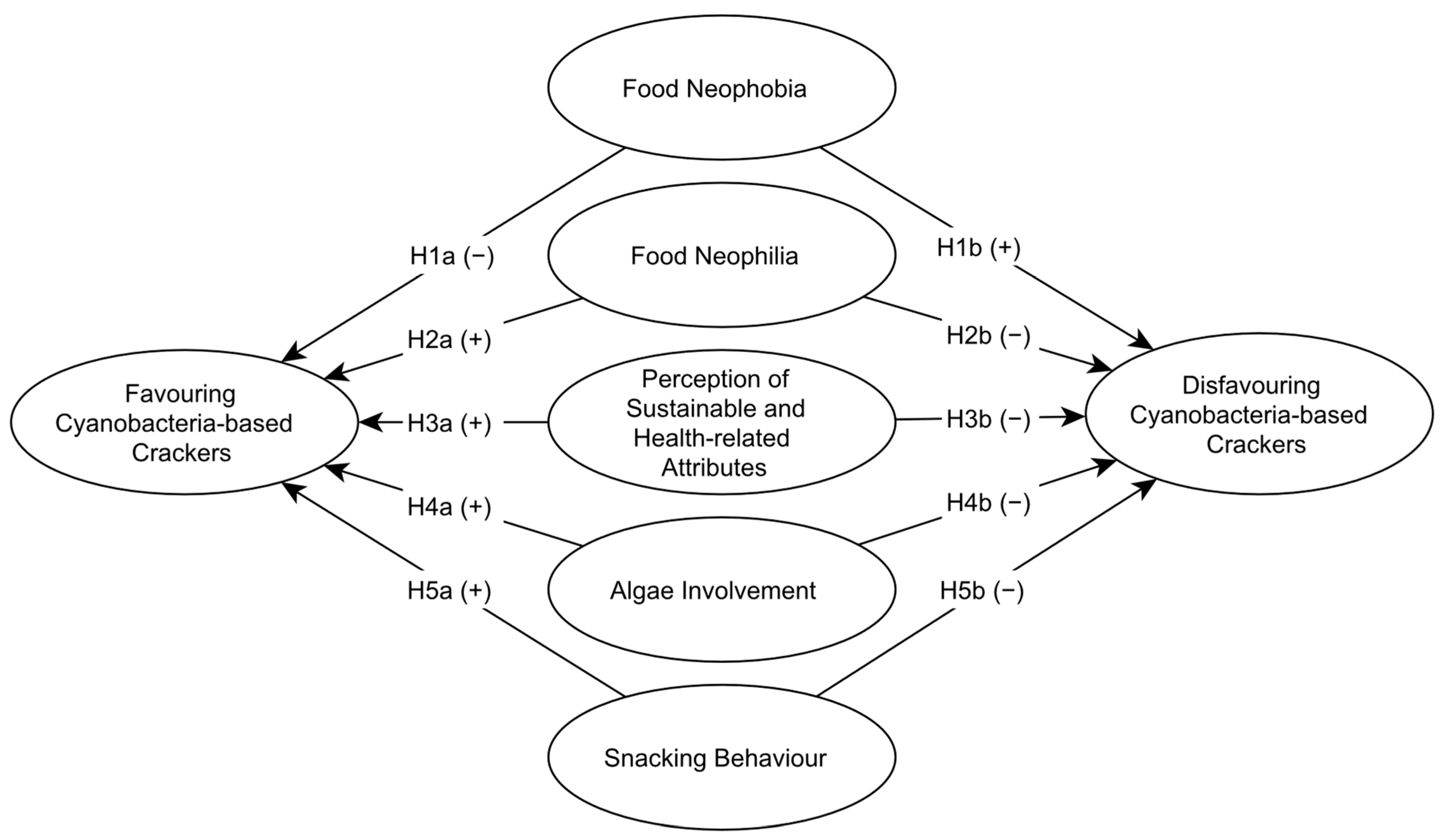

2. Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Food Neophobia and Food Neophilia

2.2. Perception of Sustainable and Health-Related Product Attributes

2.3. Involvement with Algae

2.4. Snacking Behaviour

3. Methods

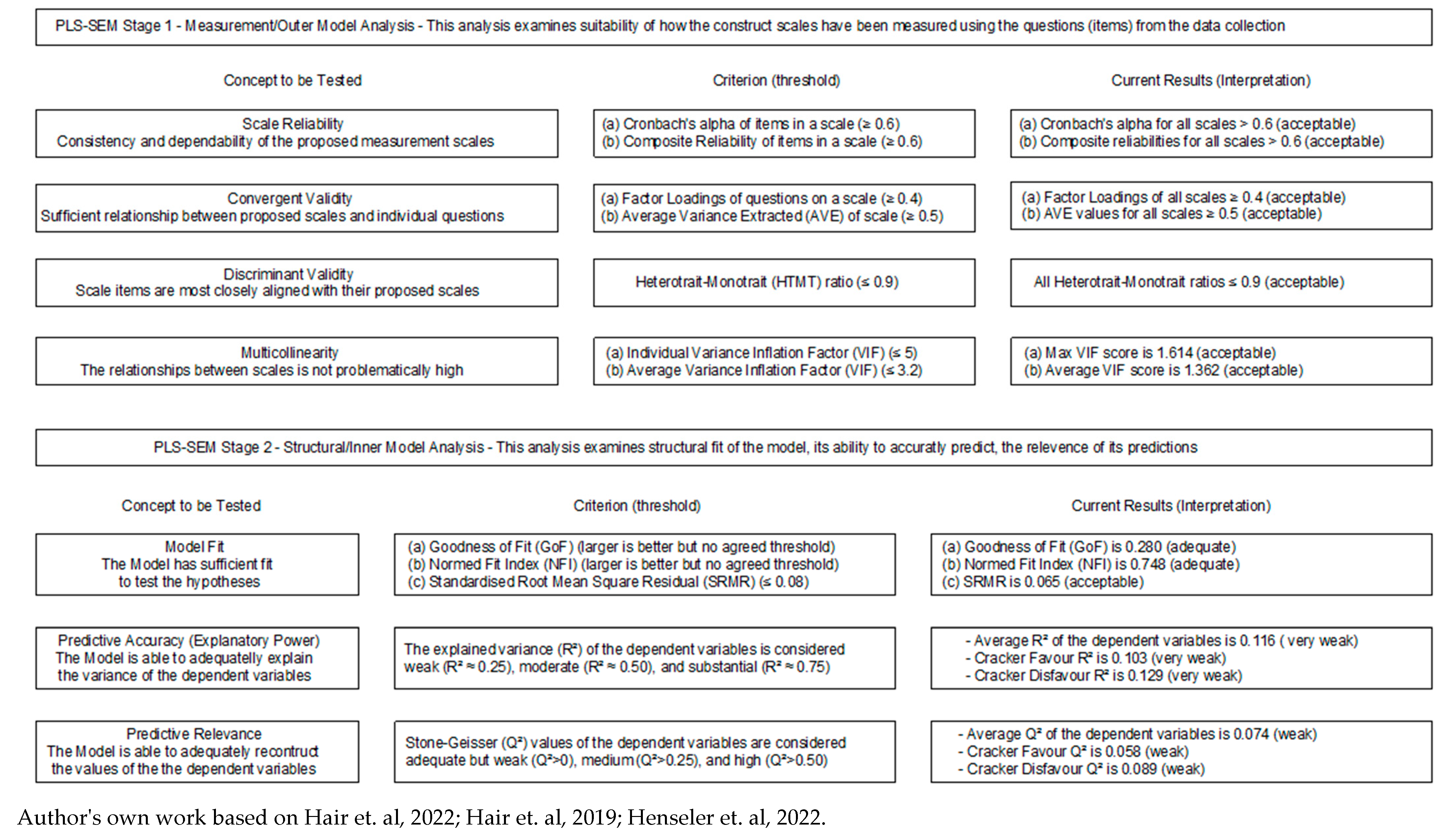

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monaco, A. Regulatory barriers and incentives for alternative proteins in the European Union and Australia–New Zealand. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giezenaar, C.; Coetzee, P.; Godfrey, A.J.R.; Foster, M.; Hort, J. Motivators and barriers to plant-based product consumption across Aotearoa New Zealand flexitarians. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 117, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Driver, T.; Zhang, R.; Guenther, M.; Duff, S.; Craigie, C.R.; Saunders, C.; Farouk, M.M. Survey of New Zealand consumer attitudes to consumption of meat and meat alternatives. Meat Sci. 2023, 203, 109232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, A.E.; Garnett, T.; Lorimer, J. Framing the future of food: The contested promises of alternative proteins. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2019, 2, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviolette, C.; Godin, L. Cultivating change in food consumption practices: The reception of the social representation of alternative proteins by consumers. Appetite 2024, 199, 107391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M.; Dean, D.L. Eating Macro-Algae (Seaweed): Understanding Factors Driving New Zealand Consumers’ Willingness to Eat and Their Perceived Trust towards Country of Origin. Foods 2024, 13, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombach, M.; Dean, D.L. Snacks, sweets, soups, salads and shakes: Investigating predictors of kiwi consumers’ willingness to recommend and pay more for sea-vegetable products. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.L.; Harrison, J.; Barnes, J. Mapping prevalence and patterns of use of, and expenditure on, traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in New Zealand: A scoping review of qualitative and quantitative studies. N. Z. Med. J. 2021, 134, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Lim, A.J.; Lin, J.W.X.; Oh, G.; Teo, P.S.; Bowie, D.; Samuelsson, L.M.; Chan, J.C.Y.; Bee Ng, S.; Foster, M.; et al. Perception and acceptance of high seaweed content novel foods (Ulva spp. and Undaria pinnatifida) across New Zealand and Singaporean consumers. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.; Major, R.; South, P.; Ogilvie, S.; Romanazzi, D.; Adams, S. Stocktake and Characterisation of New Zealand’s Seaweed Sector: Species Characteristics and Te Tiriti O Waitangi Considerations Sustainable Seas, Ko Ngā Moana Whakauka. 2021. Available online: https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/our-research/building-a-seaweed-economy (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Butcher, H.; Burkhart, S.; Paul, N.; Tiitii, U.; Tamuera, K.; Eria, T.; Swanepoel, L. Role of Seaweed in Diets of Samoa and Kiribati: Exploring Key Motivators for Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahl, S.; Strack, M.; Weinrich, R.; Mörlein, D. Consumer-oriented product development: The conceptualization of novel food products based on spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) and resulting consumer expectations. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 1919482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantechi, T.; Contini, C.; Casini, L. Pasta goes green: Consumer preferences for spirulina-enriched pasta in Italy. Algal Res. 2023, 75, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaró-Cos, S.; Sánchez, J.L.G.; Acién, G.; Lafarga, T. Research trends and current requirements and challenges in the industrial production of spirulina as a food source. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhila, N.O.; Kiselev, E.G.; Shishatskaya, E.I.; Ghorabe, F.D.; Kazachenko, A.S.; Volova, T.G. Comparative study of the synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates by cyanobacteria Spirulina platensis and green microalga Chlorella vulgaris. Algal Res. 2025, 85, 103826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.V.; Benemann, J.; Vonshak, A.; Belay, A.; Ras, M.; Unamunzaga, C.; Rizzo, A. Spirulina in the 21st century: Five reasons for success in Europe. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga-Souto, R.N.; Bürck, M.; Nakamoto, M.M.; Braga, A.R.C. Cracking Spirulina flavor: Compounds, sensory evaluations, and solutions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovando, C.A.; Carvalho, J.C.D.; Vinícius de Melo Pereira, G.; Jacques, P.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. Functional properties and health benefits of bioactive peptides derived from Spirulina: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2018, 34, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Driessche, J.J.; Plat, J.; Konings, M.C.; Mensink, R.P. Effects of spirulina and wakame consumption on intestinal cholesterol absorption and serum lipid concentrations in non-hypercholesterolemic adult men and women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 2229–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Primary Industry. Project Investigating Viability of Large-Scale Spirulina Production in New Zealand. Available online: https://www.mpi.govt.nz/news/media-releases/project-investigating-viability-of-large-scale-spirulina-production-in-new-zealand/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Foodnavigator Asia. Exotic Meets Provenance’ Frucor Suntory highlights Rising NZ Consumer Demand for Unique Juice Flavours Beyond Citrus. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator-asia.com/Article/2021/10/26/Exotic-meets-provenance-Frucor-Suntory-highlights-rising-NZ-consumer-demand-for-unique-juice-flavours-beyond-citrus/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Birch, D.; Skallerud, K.; Paul, N.A. Who are the future seaweed consumers in a Western society? Insights from Australia. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Skallerud, K.; Paul, N. Who eats seaweed? An Australian perspective. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Paul, N.; Birch, D.; Swanepoel, L. Factors Influencing the Consumption of Seaweed amongst Young Adults. Foods 2022, 11, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabitti, N.S.; Bayudan, S.; Laureati, M.; Neugart, S.; Schouteten, J.J.; Apelman, L.; Dahlstedt, S.; Sandvik, P. Snacks from the sea: A cross-national comparison of consumer acceptance for crackers added with algae. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2193–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürck, M.; Lemes, A.C.; Egea, M.B.; Braga, A.R.C. Exploring the Potential and Challenges of Fermentation in Creating Foods: A Spotlight on Microalgae. Fermentation 2024, 10, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Segovia, P.; García Alcaraz, V.; Tárrega, A.; Martínez-Monzó, J. Consumer perception and acceptability of microalgae-based breadstick. Food Sci. D Technol. Int. 2020, 26, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, A.M. Consumers’ Perspectives Regarding the Nutraceutical Nature of Spirulina: Perceptions of the Nourishing-Naturalness and Tastiness Tablets Vs Flakes. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2025, 37, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.L.; Olsen, K.; Jensen, P.E. Consumer acceptance of microalgae as a novel food- Where are we now? And how to get further. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahl, S.; Strack, M.; Mensching, A.; Mörlein, D. Alternative protein sources in Western diets: Food product development and consumer acceptance of spirulina-filled pasta. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istijanto; Arifin, Y.; Nurhayati. Examining customer satisfaction and purchase intention toward a new product before its launch: Cookies enriched with spirulina. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2257346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Baroni, M.; Fiorenza, M.; Bellotti, M.; Neri, G.; Guazzini, A. Readiness to Change and the Intention to Consume Novel Foods: Evidence from Linear Discriminant Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Khan Niazi, M.A.; Zafar, S. Food is fuel for tourism: Understanding the food travelling behaviour of potential tourists after experiencing ethnic cuisine. J. Vacat. Mark. 2025, 31, 274–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Castillo, S.; Espinoza-Ortega, A.; Sánchez-Vega, L. Perception of non-conventional food consumption: The case of insects. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyraz, S.S.; Ciftci, S. Mother’s food neophobia and eating disorder: Are they associated with child’s eating behavior? A study of mother-child pairs. Child. Health Care 2025, 54, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, N.; Gul, F.H. The relationships among food neophobia, mediterranean diet adherence, and eating disorder risk among university students: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcadu, M.; Cataldo, R.; Migliorini, L. Eating away from home: A quantitative analysis of food neophobia (FNS) and satisfaction with food life (SWFLS) scales among university students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 131, 105573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długoński, Ł.; Skotnicka, M.; Zborowski, M.; Skotnicki, M.; Folwarski, M.; Bromage, S. The Relationship Between the Level of Food Neophobia and Children’s Attitudes Toward Selected Food Products. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, F. Improvement of the nutritional value of biscuits by the addition of Spirulina powder and consumer acceptance. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2022, 28, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewska, M.; Dąbrowska, A.; Cano-Lamadrid, M. Sustainable Protein Sources: Functional Analysis of Tenebrio molitor Hydrolysates and Attitudes of Consumers in Poland and Spain Toward Insect-Based Foods. Foods 2025, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Hwang, J.S.; Kwak, H.S. Influence of Food Neophobia Levels on Recognition, Experience, Liking and Willingness-to-Try Foods of Varying Familiarity. J. Sens. Stud. 2025, 40, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.; Khalid, S.; Alomar, T.S.; AlMasoud, N.; Ansar, S.; Ghazal, A.F.; Kaddour, A.A.; Aadil, R.M. Ultrasound assisted natural deep eutectic solvents based sustainable extraction of Spirulina platensis and orange peel extracts for the development of strawberry-cantaloupe based novel clean-label functional drink. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 118, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aldana, D.; López, O.A.P.; Ley, F.J.C. Spirulina as a Novel Bioactive Material in Edible Films and Coatings as Sustainable Packaging Systems. In Food Security, Safety, and Sustainability; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilia, B.E.; Fibri, D.L.N.; Rahayu, E.S. Development and characterization of high-protein flakes made from Spirulina platensis in instant cereal drinks enriched with probiotic milk powder. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2025, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Marshall, D.W. The construct of food involvement in behavioral research: Scale development and validation☆. Appetite 2003, 40, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, I.; Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. The determinants of the adoption intention of eco-friendly functional food in different market segments. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Beaven, S.; Gaw, S.; Pearson, A.J. Shellfish consumption and recreational gathering practices in Northland, New Zealand. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 47, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotman, V.; Jeffs, A. The Aquaculture and Market Opportunities for New Zealand Seaweed Species. 2021. Available online: https://www.aquaculturescience.org/aquaculture-and-marketing-opportunities-nz-seaweed/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Gilham, B.; Hall, R.; Woods, J.L. Vegetables and legumes in new Australasian food launches: How are they being used and are they a healthy choice? Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boas, T.C.; Christenson, D.P.; Glick, D.M. Recruiting large online samples in the United States and India: Facebook, mechanical turk, and qualtrics. Political Sci. Res. Methods 2020, 8, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, F.G.; Couper, M.P.; Tourangeau, R.; Zhang, C. Reducing speeding in web surveys by providing immediate feedback. Surv. Res. Methods 2017, 11, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greszki, R.; Meyer, M.; Schoen, H. Exploring the effects of removing “too fast” responses and respondents from web surveys. Public Opin. Q. 2015, 79, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.E.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premordia, I.; Gál, T. Food neophilics’ choice of an ethnic restaurant: The moderating role of authenticity. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, L.A.; Pope, L.; Wansink, B. Food neophiles: Profiling the adventurous eater. Obesity 2015, 23, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, S.; Florack, A.; Campuzano, I.; Alves, H. The sustainability liability revisited: Positive versus negative differentiation of novel products by sustainability attributes. Appetite 2021, 167, 105637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, S.d.P.; Bürck, M.; Costa, S.F.F.d.; Assis, M.; Braga, A.R.C. Spirulina as a Key Ingredient in the Evolution of Eco-Friendly Cosmetics. BioTech 2025, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Esponda-Perez, J.A.; Millones-Liza, D.Y.; Haro-Zea, K.L.; Moreno-Barrera, L.A.; Ezcurra-Zavaleta, G.A.; Rivera-Echegaray, L.A.; Escobar-Farfan, M. The Influence of Healthy Lifestyle on Willingness to Consume Healthy Food Brands: A Perceived Value Perspective. Foods 2025, 14, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frewer, L.J. Risk Perception, Communication and Food Safety. In Strategies for Achieving Food Security in Central Asia; Alpas, H., Smith, M., Kulmyrzaev, A., Eds.; NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S. Customer experience and sustainability in social, environmental and economic contexts. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Snack Food New Zealand. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/confectionery-snacks/snack-food/new-zealand (accessed on 12 June 2025).

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | NZ Census | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | |||

| 18–24 years old | 62 | 14.2 | 12.2 |

| 25–34 years old | 79 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| 35–44 years old | 72 | 16.5 | 16.3 |

| 45–54 years old | 77 | 17.6 | 17.5 |

| 55–64 years old | 62 | 14.2 | 15.7 |

| 65 years old and older | 85 | 19.5 | 19.9 |

| Total | 437 | 100 | 100 |

| Household Income Group (per Year in NZD) | |||

| NZD 0 to NZD 24,999 | 50 | 11.4 | 19 |

| NZD 25,000 to NZD 49,999 | 125 | 28.6 | 40 |

| NZD 50,000 to NZD 74,999 | 116 | 26.5 | 24 |

| NZD 75,000 to NZD 99,999 | 65 | 14.9 | 11 |

| NZD 100,000 or higher | 81 | 18.5 | 6 |

| Total | 437 | 100 | 100 |

| Gender Group | |||

| Female | 224 | 51.3 | 50.7 |

| Male | 213 | 48.8 | 49.4 |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 437 | 100 | 100 |

| Scales and Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Neophilia | 0.727 | 0.829 | 0.550 | |

| I like to try new ethnic restaurants. | 0.807 | |||

| I like foods from different cultures. | 0.750 | |||

| At dinner parties, I will try new foods | 0.798 | |||

| I will eat almost anything | 0.631 | |||

| Food Neophobia | 0.792 | 0.863 | 0.613 | |

| I don’t trust new foods | 0.750 | |||

| If I don’t know what the food is, I won’t try it. | 0.733 | |||

| Ethnic food looks too weird to eat | 0.824 | |||

| I am afraid to eat things I have never had before. | 0.820 | |||

| Algae involvement | 0.734 | 0.828 | 0.561 | |

| I have been foraging for algae | 0.786 | |||

| I am committed to food processing and food preserving | 0.764 | |||

| I have watched YouTube videos about algae production | ||||

| I know how to identify algae | 0.757 | |||

| Perception of sustainable and health-related product attributes of Cyanobacteria-based Cracker | 0.872 | 0.889 | 0.527 | |

| Healthy | 0.788 | |||

| Nutritious | 0.638 | |||

| Good source of Omega 3 acids | 0.607 | |||

| Low in calories | 0.818 | |||

| Good Source of iodine | 0.698 | |||

| Sustainable | 0.683 | |||

| Product from the seafood industry | 0.770 | |||

| Good Source of protein | 0.779 | |||

| Snacking behaviour | 0.865 | 0.917 | 0.786 | |

| I eat a lot of snacks rather than having set mealtimes | 0.887 | |||

| I tend to snack during the day, which often means I am not hungry at mealtimes. | 0.876 | |||

| I eat a lot of small meals rather than keeping to fixed mealtimes. | 0.896 | |||

| Favouring Cyanobacteria-based Cracker | 0.722 | 0.843 | 0.705 | |

| I could eat this cracker | 0.837 | |||

| I would prefer this over crackers without spirulina | 0.730 | |||

| Adding spirulina like this makes it better | 0.831 | |||

| Disfavouring Cyanobacteria-based Cracker | 0.788 | 0.877 | 0.642 | |

| Adding Spirulina like this is a bad idea (1) | 0.900 | |||

| It is inappropriate to use Spirulina in this way | 0.867 | |||

| This cracker will taste worse than a cracker without spirulina | 0.744 |

| HTMT | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Disfavouring cyanobacteria-based crackers | |||||||

| (B) Favouring cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.527 | ||||||

| (C) Food neophilia | 0.305 | 0.245 | |||||

| (D) food neophobia | 0.335 | 0.1 | 0.663 | ||||

| (E) Algae Involvement | 0.07 | 0.235 | 0.163 | 0.254 | |||

| (F) Perception of health and sustainability-related product attributes | 0.25 | 0.295 | 0.332 | 0.177 | 0.329 | ||

| (G) Snacking Behaviour | 0.21 | 0.086 | 0.158 | 0.301 | 0.339 | 0.104 |

| Hypothesised Relationship | Coefficient | T Stat | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Food neophobia → Favouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.052 | 0.65 | 0.516 |

| H1b: Food neophobia → Disfavouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.130 | 1.714 | 0.087 |

| H2a: Food neophilia → Favouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.151 | 1.971 | 0.049 |

| H2b: Food neophilia → Disfavouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | −0.144 | 2.157 | 0.031 |

| H3a: Perception of health- and sustainability-related product attributes → Favouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.163 | 3.036 | 0.002 |

| H3b: Perception of health- and sustainability-related product attributes → Disfavouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | −0.145 | 2.776 | 0.006 |

| H4a: Algae involvement → Favouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.132 | 2.61 | 0.009 |

| H4b: Algae involvement → Disfavouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.019 | 0.387 | 0.698 |

| H5a: Snacking behaviour → Favouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | −0.081 | 1.624 | 0.104 |

| H5b: Snacking behaviour → Disfavouring Cyanobacteria-based crackers | 0.143 | 2.968 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rombach, M.; Dean, D.L. Snack Attack: Understanding Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Favour and Disfavour for Cyanobacteria (Blue-Green Algae)-Based Crackers. Phycology 2025, 5, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5030034

Rombach M, Dean DL. Snack Attack: Understanding Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Favour and Disfavour for Cyanobacteria (Blue-Green Algae)-Based Crackers. Phycology. 2025; 5(3):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleRombach, Meike, and David L. Dean. 2025. "Snack Attack: Understanding Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Favour and Disfavour for Cyanobacteria (Blue-Green Algae)-Based Crackers" Phycology 5, no. 3: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5030034

APA StyleRombach, M., & Dean, D. L. (2025). Snack Attack: Understanding Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Favour and Disfavour for Cyanobacteria (Blue-Green Algae)-Based Crackers. Phycology, 5(3), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5030034