Adaptation to Stressful Environments in Sheep and Goats: Key Strategies to Provide Food Security to Vulnerable Communities

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy and Selection of Literature

3. Results

3.1. Production System and Its Impact on the Adaptation to the Environment

3.2. Small Ruminants as a Model of Adaptation

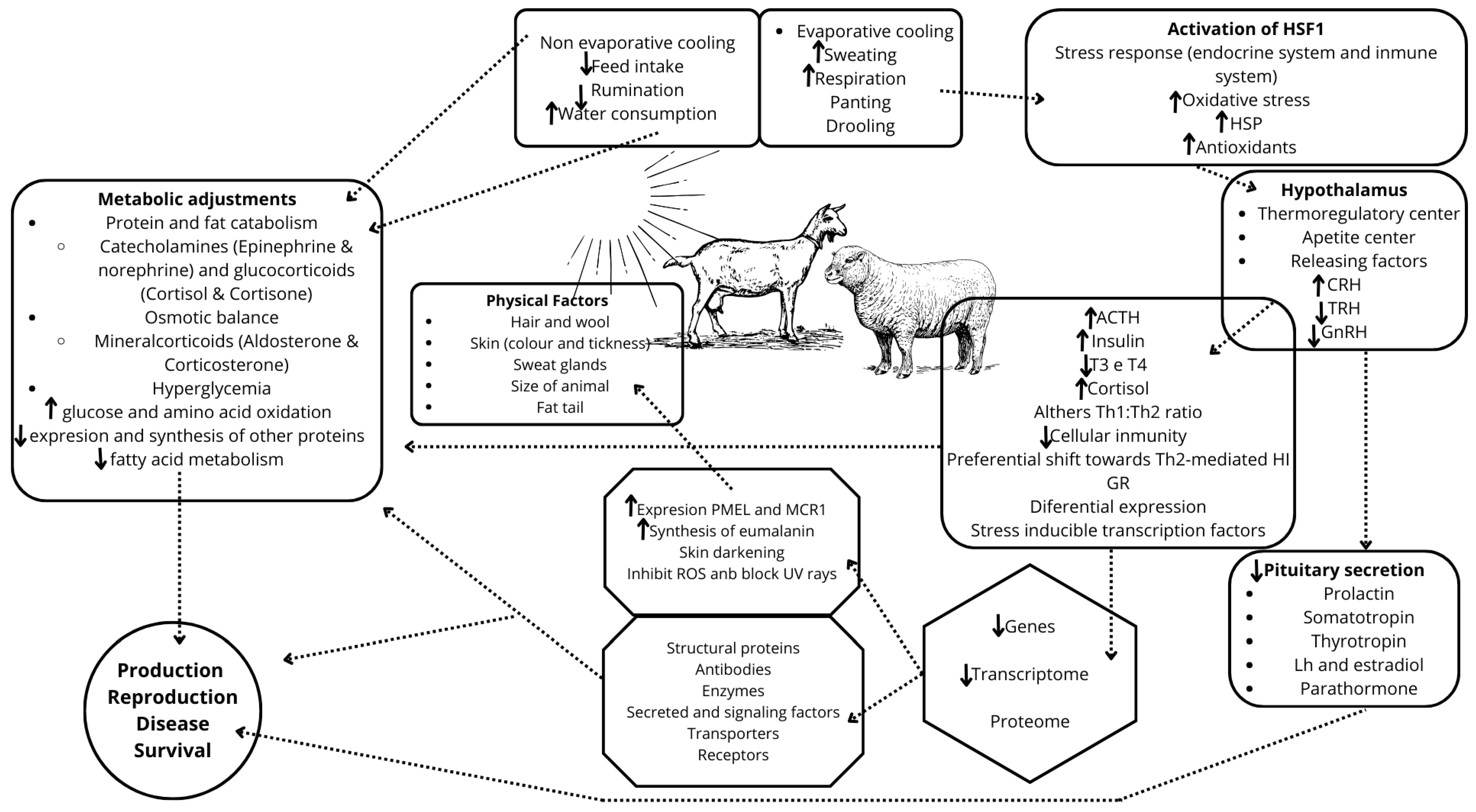

3.3. Anatomic and Metabolic Adaptations

3.4. Criteria and Variables Employed to Measure Adaptation in Small Ruminants

3.4.1. Ethology and Corporal Response

3.4.2. Phenotypic Typology

3.5. Metabolic Response Under Stress

3.6. Long-Term Implications in Adaptive Processes in the Genetic Improvement of Small Ruminants

4. Future Perspectives for Small Ruminant Breeding in a Changing Climate

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSP | Heat shock protein |

| THI | Temperature–humidity index |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acids |

| GI | Gastrointestinal tract |

| GIN | Gastrointestinal nematodes |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. |

References

- Brumfield, K.D.; Usmani, M.; Long, H.A.; Lupari, D.M.; Pope, R.K.; Jutla, A.S.; Huq, A.; Colwell, R.R. Climate change and Vibrio: Environmental determinants for predictive risk assessment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2420423122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcamu, B.S. Climate change effects on vulnerable populations in the Global South: A systematic review. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Hernández, G.; Maldonado-Jáquez, J.A.; Granados-Rivera, L.D.; Salinas-González, H.; Castillo-Hernández, G. Status quo of genetic improvement in local goats: A review. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2022, 65, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Cervantes, R.E. Vulnerabilidad y riesgo como conceptos indisociables para el estudio del impacto del cambio climático en la salud. Reg. Soc. 2018, 30, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, H.; Azita, A. Addressing food insecurity in vulnerable populations. Am. J. Nurs. 2019, 119, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodajo, H.D.; Gemeda, B.A.; Kinati, W.; Mulem, A.A.; van Eerdewijk, A.; Wieland, B. Contribution of small ruminants to food security for Ethiopian smallholder farmers. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 184, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R.J.; Renquist, B.J.; Xiao, Y. A 100-year review: Stress physiology including heat stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10367–10380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, P.M. What is environmental stress? Insights from fish living in a variable environment. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinmoladun, O.F.; Muchenje, V.; Fon, F.N.; Mpendulo, C.T. Small Ruminants: Farmers’ Hope in a World Threatened by Water Scarcity. Animals 2019, 9, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleke, F.B.; Berhe, M.; Gebru, G.; Hoag, D. Determinants of adaptation choices to climate change by sheep and goat farmers in northern Ethiopia: The case of southern and central Tigray, Ethiopia. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcan, N.K.; Silanikove, N. The advantages of goats for future adaptation to Climate Change: A conceptual overview. Small Rumin Res. 2017, 163, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshma Nair, M.R.; Sejian, V.; Silpa, M.V.; Fonsêca, V.F.C.; de Melo Costa, C.C.; Devaraj, C.; Krishnan, G.; Bagath, M.; Nameer, P.O.; Bhatta, R. Goat as the ideal climate-resilient animal model in tropical environment: Revisiting advantages over other livestock species. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 2229–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berihulay, H.; Abied, A.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Adaptation Mechanisms of Small Ruminants to Environmental Heat Stress. Animals 2019, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runa, R.A.; Brinkmann, L.; Gerken, M.; Riek, A. Adaptation capacity of Boer goats to saline drinking water. Animal 2019, 13, 2268–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilja, S.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Mech, A.; David, C.G.; Kurien, E.K.; Varma, G.; Bhatta, R. Adaptive capability as indicated by behavioral and physiological responses, plasma HSP70 level, and PBMC HSP70 mRNA expression in Osmanabadi goats subjected to combined (heat and nutritional) stressors. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 60, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archana, P.R.; Aleena, J.; Pragna, P.; Viya, M.K.; Abul Niyas, P.A.; Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Manimaran, A.; Beena, V.; Sejian, V.; et al. Role of heat shock proteins in livestock adaptation to heat stress. J. Dairy Vet. Anim. Res. 2017, 5, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejian, V.; Bhatta, R.; Soren, N.M.; Malik, P.K.; Ravindra, J.P.; Prasad, C.S.; Lal, R. Introduction to Concepts of Climate Change Impact on Livestock and Its Adaptation and Mitigation; Springer: Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, C.; Dagan, T.; Deines, P.; Dubilier, N.; Dushl, W.J.; Fraune, S.; Hentschel, U.; Hirt, H.; Hülter, N.; Lachnit, T.; et al. Meta organisms in extreme environments: Do microbes play a role in organismal ad-aptation? Zoology 2018, 127, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais Leite, J.H.G.; Evangelista Façanha, D.A.; Delgado-Bermejo, J.V.; Guilhermino, M.M.; Bermejo, L.A. Adaptive assessment of small ruminants in arid and semiarid regions. Small Rumin. Res. 2021, 203, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wu, C.; Sammad, A.; Ma, Z.; Suo, L.; Wu, Y.; Fu, X. The fiber diameter traits of Tibetan cashmere goats are governed by the inherent differences in stress, hypoxic, and metabolic adaptations: An integrative study of proteome and transcriptome. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abied, A.; Bagadi, A.; Bordbar, F.; Pu, Y.; Augustino, S.M.A.; Xue, X.; Xing, F.; Gebreselassie, G.; Han, J.-L.; Mwacharo, J.M.; et al. Genomic Diversity, Population Structure, and Signature of Selection in Five Chinese Native Sheep Breeds Adapted to Extreme Environments. Genes 2020, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewdu, E.; Hailu, D.; Tadelle, D.; Kwan-Suk, K. Genomic signatures of high-altitude adaptation in Ethiopian sheep populations. Genes Genom. 2019, 41, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarazaga, L.Á.; Gatica, M.-C.; De La Rosa, I.; Delgado-Pertíñez, M.; Guzmán, J.L. The High Testosterone Concentrations of the Bucks Used in the “Male Effect” Is Not a Prerequisite for Obtaining High Ovarian Activity in Goats from Mediterranean Latitudes. Animals 2022, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhlouf, A.; Titaouine, M.; Mohamdi, H.; Yakoub, F. Effect of differential altitude on reproductive performance and mineral assessment in Ouled Djelal ewes during the mating period. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 3275–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mili, B.; Chutia, T. Adaptive mechanisms of goat to heat stress. In Goat Science—Environment, Health and Economy; Kukovics, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista Façanha, D.A.; Ferreira, J.; Freitas Silveira, R.M.; Nunes, T.L.; de Oliveira, M.G.C.; de Sousa, J.E.R.; de Paula, V.V. Are locally adapted goats able to recover homeothermy, acid-base and electrolyte equilibrium in a semi-arid region? J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 90, 102593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonsêca, W.J.L.; Azevêdo, D.M.M.R.; Campelo, J.E.G.; Fonseca, W.L.; Luz, C.S.M.; Oliveira, M.R.A.; Evangelista, A.F.; Borges, L.S.; Sousa-Júnior, S.C. Effect of heat stress on milk production of goats from Alpine and Saanen breeds in Brazil. Arch. Zootec. 2016, 65, 615–621. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, A.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; Clarke, I.J.; DiGiacomo, K.; Chauhan, S.S. Resilience of Small Ruminants to Climate Change and Increased Environmental Temperature: A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Hernández, G.; Maldonado-Jáquez, J.A.; Granados-Rivera, L.D.; Wurzinger, M.; Cruz-Tamayo, A.A. Creole goats in Latin America and the Caribbean: A priceless resource to ensure the well-being of rural communities. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2022, 20, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thuwaini, T.M. The relationship of hematological parameters with adaptation and reproduction in sheep; a review study. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 2021, 35, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul Naga, A.M.; Abdel Khalek, T.M.; Osman, M.; Elbeltagy, A.R.; Abdel-Aal, E.S.; Abou-Ammo, F.F.; El-Shafie, M.H. Physiological and genetic adaptation of desert sheep and goats to heat stress in the arid areas of Egypt. Small Rumin Res. 2021, 203, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, N.; Sejian, V. Climate resilience of goat breeds in India: A review. Small Rumin Res. 2022, 206, 106630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcangiu, V.; Arfuso, F.; Luridiana, S.; Giannetto, C.; Rizzo, M.; Bini, P.P.; Piccione, G. Relationship between different livestock managements and stress response in dairy ewes. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2018, 61, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moutchou, N.; González, A.M.; Chentouf, M.; Lairini, K.; Rodero, E. Morphological differentiation of northern Morocco goat. J. Livest. Sci. Technol. 2017, 5, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullakkalparambil Velayudhan, S.; Sejian, V.; Devaraj, C.; Manjunathareddy, G.B.; Ruban, W.; Kadam, V.; König, S.; Bhatta, R. Novel insights to asses climate resilience in goats using a holistic approach of skin-based advanced technologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz-Domínguez, G.A.; Marín-Tun, C.G.; Torres-Fajardo, R.A.; González-Pech, P.G.; Capetillo-Leal, C.M.; Torres-Acosta, J.F.J.; Ventura-Cordero, J.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A. Selection of forage resources by juvenile goats in a cafeteria trial: Effect of browsing experience, nutrient and secondary compound content. Animals 2022, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Mao, S.; Zhu, W.; Liu, J. Proteomic identification of ruminal epithelial protein expression profiles in response to starter feed supplementation in pre-weaned lambs. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.H.; Ward, D.; Shrader, A.M. Salivary tannin-binding proteins: A foraging advantage for goats? Livest. Sci. 2020, 234, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Koluman, N.D. Impact of climate change on the dairy industry in temperate zones: Predications on the overall negative impact and on the positive role of dairy goats in adaptation to earth warming. Small Rumin. Res. 2015, 12, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.E.S. Physiological, hematological and biochemical alterations in heat stressed goats. Benha Vet. Med. J. 2016, 31, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rout, P.K.; Kaushik, R.; Ramachandran, N. Differential expression pattern of heat shock protein 70 gene in tissues and heat stress phenotypes in goats during peak heat stress period. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Foren, A.; Meikle, A.; de Brun, V.; Graña-Baumgartner, A.; Abecia, J.A.; Sosa, C. Metabolic memory determines gene expression in liver and adipose tissue of undernourished ewes. Livest. Sci. 2022, 260, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoui, A.; Najari, S.; Díaz, C.; Abdennebi, M.; Carabaño, M.J. On the modelling of weights of kids to enhance growth in a local goat population under Tunisian arid conditions: The maternal effects. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeltagy, A.R.; Aboul Naga, A.M.; Hassen, H.; Solouma, G.M.; Rischkowsky, B.; Mwacharo, J.M. Genetic diversity and structure of goats within an early livestock dispersal area in Eastern North Africa. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwacharo, J.M.; Kim, E.S.; Elbeltagy, A.R.; Aboul-Naga, A.M.; Rischkowsky, B.A.; Rothschild, M.F. Genomic footprints of dryland stress adaptation in Egyptian fat-tail sheep and their divergence from East African and western Asia cohorts. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes Neto, J.P.; Marques, J.I.; Furtado, D.A.; Lopes, F.F.d.M.; Borges, V.P.; Araújo, T.G.P. Pupillary stress index: A new thermal comfort index for crossbred goats. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agric. Ambient. 2018, 22, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Báez, P.; Torres-Hernández, G.; Castillo-Hernández, G.; Hernández-Rodríguez, M.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, R.A.; Vargas-López, S.; González-Maldonado, J.; Domínguez-Martínez, P.A.; Granados-Rivera, L.D.; Maldonado-Jáquez, J.A. Coat Color in Local Goats: Influence on Environmental Adaptation and Productivity, and Use as a Selection Criterion. Biology 2023, 12, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.; Freitas Silveira, R.M.; de Sousa, J.E.R.; Vasconselos, A.M.; Guilhermino, M.M.; Evangelista Façanha, D.A. Evaluation of homeothermy, acid-base and electrolytic balance of black goats and ewes in an equatorial semi-arid environment. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 100, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart-Fox, D.; Newton, E.; Clusella-Trullas, S. Thermal consequences of colour and near-infrared reflectance. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B or Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokoe, T.C.; Matelele, T.C.; Maqhashu, A.; Ramukhithi, F.V.; Mphahlele, T.D.; Mpofu, T.J.; Nephawe, K.A.; Mtileni, B. Phenotypic diversity of South African indigenous goat population in selected rural areas. Am. J. Anim. Vet. 2020, 15, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Jáquez, J.A.; Arenas-Báez, P.; Garay-Martínez, J.R.; Granados-Rivera, L.D. Body composition as a function of coat color, sex and age in local kids from northern Mexico. Agrociencia 2023, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, C.M.; Lucci, C.M.; Maranhao, A.Q.; Pimentel, D.; Pimentel, F.; Rezende-Paiva, S. Response to heat stress for small ruminants: Physiological and genetic aspects. Livest. Sci. 2022, 263, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, A.R. Effects of long-term restricted feeding on digestion and energy utilization in Balady vs. Shami goats. Livest. Sci. 2016, 185, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, C.; Del Viento, A.; Palma, J.M. Preferencia y consumo de diferentes partes morfológicas de Ricinus communis L. (higuerilla) por ovinos. Av. En Investig. Agropecu. 2016, 20, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño-Reyes, L.; Macías-Cruz, U.; Correa-Calderón, A.; Mellado, M.; Corrales, J.L.; Ramírez-Bribiesca, E.; Guerra-Liera, J.E. Biological responses of hair sheep to a permanent shade during a short heat stress exposure in an arid region. Small Rumin Res. 2020, 189, 106146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenyi, S.P.; Birindwa, A.B.; Mutwedu, V.B.; Mugumaarhahama, Y.; Munga, A.; Mitima, B.; Kamgang, V.W.; Ayagirwe, R.B.B. Effects of coat color pattern and sex on physiological traits and heat tolerance of indigenous goats ex-posed to solar radiation. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2020, 8, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Elbeltagy, A.R.; Aboul-Naga, A.M.; Rischkowsky Sayre, B.; Mwacharo, J.M.; Rothschild, M.F. Multiple genomic signatures of selection in goats and sheep indigenous to a hot arid environment. Heredity 2016, 116, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Santini, L.; Ríos de Álvarez, L.; Oliveros, I.; Pigliacampo, A.; Chacón, T. Índices fisiológicos em corderas tipo West African con acceso voluntario a sombra artificial bajo condiciones de emergencia de calor leve. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2014, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pragna, P.; Sejian, V.; Soren, N.M.; Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Beena, V.; Indira Devi, P.; Bhatta, R. Summer season induced rhythmic alterations in metabolic activities to adapt to heat stress in three indigenous (Osmanabadi, Malabari and Salem Black) goat breeds. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2017, 49, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, W.R.; Lv, F.H.; He, S.G.; Tian, S.L.; Peng, W.F.; Sun, Y.W.; Zhao, Y.X.; Tu, X.L.; Zhang, M.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing of native sheep provides insights into rapid adaptations to extreme environments. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 2576–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarekegn, G.M.; Khayatzadeh, N.; Liu, B.; Osama, S.; Haile, A.; Rischkowsky, B.; Zhang, W.; Tesfaye, K.; Dessie, T.; Mwai, O.A.; et al. Ethiopian indigenous goats offer insights into past and recent demo-graphic dynamics and local adaptation in sub-Saharan African goats. Evol. Appl. 2020, 14, 1716–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Q.; Cui, X.; Wang, Z.; Chang, S.; Wanapat, M.; Yan, T.; Hou, F. Rumen microbiota of Tibetan sheep (Ovis aries) adaptation to extremely cold season on the Qinhai-Tibetan plateau. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 673822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorkhali, N.A.; Dong, K.; Yang, M.; Song, S.; Kader, A.; Shrestha, B.S.; He, X.; Zhao, Q.; Pu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Genomic analysis identified a potential novel molecular mechanism for high-altitude adaptation in sheep at the Himalayas. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrangelo, S.; Moioli, B.; Ahbara, A.; Latairish, S.; Portolano, B.; Pilla, F.; Ciani, E. Genome-wide scan of fat-tail sheep identifies signals of selection for fat deposition and adaptation. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 59, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serranito, B.; Cavalazzi, M.; Vidal, P.; Taurisson-Mouret, D.; Ciani, E.; Bal, M.; Rouvellac, E.; Servin, B.; Moreno-Romieux, C.; Tosser-Klopp, G.; et al. Local adaptations of Mediterranean sheep and goats through an integrative approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, H.N.M.; Araújo Furtado, D.; Carvalho Fonsêca, V.F.; de Souza, B.B.; de Oliveira, A.G.; Leal Morais, F.T.; de Sousa Silva, R.; Rodrigues da Silva, M.; Figueiredo Batista, L.; Carvalho Dornelas, K.; et al. Thermal stress index for native sheep. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 115, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhong, J.; Li, L.; Zhong, T.; Wang, L.; Song, T.; Zhang, H. Comparative genome analyses reveal the unique genetic composition and selection signals underlying the phenotypic characteristics of three Chinese domestic goat breeds. Genet. Sel. 2019, 51, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danso, F.; Iddrisu, L.; Lungu, S.E.; Zhou, G.; Ju, X. Effects of Heat Stress on Goat Production and Mitigating Strategies: A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, T.; Haile, A.; Tessema, T.; Dea, D.; Edea, Z.; Rischkowsky, B. Participatory identification of breeding objective traits and selection criteria for indigenous goat of the pastoral communities in Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 2145–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, B.; Singh, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Kaushik, J.K.; Rao, A.R.; Ahmad, S.M.; Bhat, H.; Ayaz, A.; Sheikh, F.D.; Kalra, S.; et al. Comparativetranscriptome analysis reveals the genetic basis of coat color variation in Pashmina goat. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6361. [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberti, M.G.; Caroprese, M.; Albenzio, M. Climate resilience in small ruminant and immune system: An old al-liance in the new sustainability context. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 210, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, Z. GLIS1, a potential candidate gene affect fat deposition in sheep tail. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 4925–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, I.; Fernández, I.; Traoré, A.; Pérez-Pardal, L.; Ménendez-Arias, N.A.; Goyache, F. Genomic scan of se-lective sweeps in Djallonké (West African Dwarf) sheep shed light on adaptation to harsh environments. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadipoor-Saadatabi, L.; Mohammadabadi, M.; Amiri Ghanatsaman, Z.; Babenko, O.; Stavetska, R.; Kalashnik, O.; Kucher, D.; Kochuk-Yashchenko, O.; Asadollahpour Nanaei, H. Signature selection analysis reveals candi-date genes associated with production traits in Iranian sheep breeds. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, F.; Servin, B.; Talenti, A.; Rochat, E.; Kim, E.S.; Oget, C.; Palhière, I.; Crisà, A.; Catillo, G.; Steri, R.; et al. Signatures of selection and environmental adaptation across the goat genome pot-domestication. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2018, 50, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, J.; Saif, R.; Jagannathan, V.; Schmocker, C.; Zeindler, F.; Bangerter, E.; Herren, U.; Posantzis, D.; Bulut, Z.; Ammann, P.; et al. Selection signatures in goats reveal copy number variants underlying breed-defining coat color phenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stressor Type | Species | Breed | Country | Evaluated Traits | Conclusions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water restriction | Sheep | Morada Nova | Brasil | Rectal T°, respiratory rate coat thickness, length, diameter and fur density, hematology, hormonal profile | Hematologic, biochemical, and hormonal profiles are within the normal range in goats, confirming adaptability | [19] |

| Water restriction | Goats | Boer | Germany | Salt concentrations, water and food consumption, live weight, corporal condition | The response of the animal will vary in function of the sodium balance of the animal. | [14] |

| Digestive adaptations (fodder type/parasites) | Goats | Balady and Shami | Egypt | Heart rate, oxygenation, live weight, digestibility, energetic outcome | Balady goats are skilled in reducing their energetic outcome and improving energy balance with low energy intake. | [55] |

| Digestive adaptations (fodder type/parasites) | Sheep | Pelibuey | México | Live weight, preference of different parts of the plant, DM consumption, signs of intoxication | The animals preferred the leaf blade of Ricinis communis without signs of intoxication. | [56] |

| Heat stress | Sheep | 1Dp*Pb | México | Rectal T°, heart rate, hematology, consumption, live weight | Thermoregulation capacity is improved when using metallic shade devices; also, lack of sun protection affects food intake. | [57] |

| Heat stress | Goats | Indigenous | Congo | Coat color, food consumption, rectal T°, heart rate, hematology | There are physiological, hematologic, and biochemical variations that affect the productive and reproductive behavior in very warm environments. | [58] |

| Heat stress | Goats | Canindé | Brasil | Environmental T°, heat load, rectal T°, respiratory rate, electrolytic balance, sweating rate, pH, oxygen saturation | Variations in the thermoregulatory response and acid-base and electrolytic balance indicate that goats have the ability to recover after stressful environmental conditions. | [26] |

| Heat stress | Goats and sheep | Barki | Egypt | Gene expression | There were found candidate regions that group 119 genes involved in signs of a wide variety of cellular and biochemical processes. | [59] |

| Heat stress | Sheep | Morada Nova | Brasil | Coat color, solar exposure, coat thickness, length, diameter and hair density, rectal T°, respiratory rate, cutaneous evaporation | It was verified that coat color has a direct influence on the structure and activation of mechanisms related to thermoregulation. | [19] |

| Heat stress | Sheep | West African | Venezuela | Access to shade and sun, behavior in grazing, climate | The presence of shade seems to mitigate negative effects during grazing. | [60] |

| Heat stress | Goats | Osmanabadi Malabari Salem | India | Hormonal profile, rumen metabolites, VFA | In comparative terms, the Salem breed adapts better to the challenges of heat stress. | [61] |

| Heat stress | Goats | Canindé | Brazil | Respiratory rate, rectal T°, sweating rate, air T°, relative humidity, THI | The efficiency in body heat dynamism in local goats showed an ability to regulate the temperature. | [50] |

| Heat stress | Sheep | Native | NE | Selection signatures, environmental selection | These sheep have a set of genes associated with the response to hypoxia and water reabsorption. | [62] |

| Altitude and cold stress | Goats | Arsi-Bale y Nubian | Signature selection, environment selection | There were found signatures of adaptation in Arsi-Bale goats for altitude and low T°. In Nubian goats, they were observed for low altitudes and high T°. | [63] | |

| Altitude and cold stress | Sheep | Tibetan | Tibet | Fodder consumption, growth, hematology, FA profile, DNA sequencing | There are low degradation and fermentation values. The ruminal microbiota promotes fodder decomposition and energy maintenance with low nutritional intake. | [64] |

| Altitude and cold stress | Sheep | Indigenous | Nepal | SNP’s for gene identification | It was found that the FGF-7 gene improves pulmonary function (has not been reported in any other species). | [65] |

| Various stressors | Sheep | 21 sheep breeds | Five countries | Selection signatures, genomic information, polymorphism in markers | There were found associations to explain fat deposition in the tail as an energy-saving mechanism and climatic adaptations. | [66] |

| Various stressors | Goats and sheep | 17 goat breeds and 25 goat breeds | Italy, France, and Spain | Selection signatures, environment selection, the literature review | Genes involved in lipid metabolism were found (SUCLG2, BMP2), hypoxia stress/pulmonary function (BMPR2), seasonal patterns (SOX2, DPH6), neuronal function (TRPC4, TRPC6). And PCDH9 and KLH1 genes were found in both species. | [67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maldonado-Jáquez, J.A.; Torres-Hernández, G.; Castillo-Hernández, G.; Cruz-Colín, L.D.L.; Jiménez-Penago, G.; González-Luna, S.; Aguilar Marcelino, L.; Arenas-Báez, P.; Granados-Rivera, L.D. Adaptation to Stressful Environments in Sheep and Goats: Key Strategies to Provide Food Security to Vulnerable Communities. Ruminants 2025, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040063

Maldonado-Jáquez JA, Torres-Hernández G, Castillo-Hernández G, Cruz-Colín LDL, Jiménez-Penago G, González-Luna S, Aguilar Marcelino L, Arenas-Báez P, Granados-Rivera LD. Adaptation to Stressful Environments in Sheep and Goats: Key Strategies to Provide Food Security to Vulnerable Communities. Ruminants. 2025; 5(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaldonado-Jáquez, Jorge A., Glafiro Torres-Hernández, Gabriela Castillo-Hernández, Lino De La Cruz-Colín, Gerardo Jiménez-Penago, Sandra González-Luna, Liliana Aguilar Marcelino, Pablo Arenas-Báez, and Lorenzo Danilo Granados-Rivera. 2025. "Adaptation to Stressful Environments in Sheep and Goats: Key Strategies to Provide Food Security to Vulnerable Communities" Ruminants 5, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040063

APA StyleMaldonado-Jáquez, J. A., Torres-Hernández, G., Castillo-Hernández, G., Cruz-Colín, L. D. L., Jiménez-Penago, G., González-Luna, S., Aguilar Marcelino, L., Arenas-Báez, P., & Granados-Rivera, L. D. (2025). Adaptation to Stressful Environments in Sheep and Goats: Key Strategies to Provide Food Security to Vulnerable Communities. Ruminants, 5(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040063