Amazonian Fruit (Samanea tubulosa) in Dairy Cattle Diets: In Vitro Fermentation, Gas Production, and Digestibility

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Treatments and Experimental Design

2.2. In Vitro Assay

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.4. Calculations and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of BVP and Biological Effect

3.2. In Vitro Apparent Digestibility, Partition Factor, and Gas Production

3.3. In Vitro Fermentation

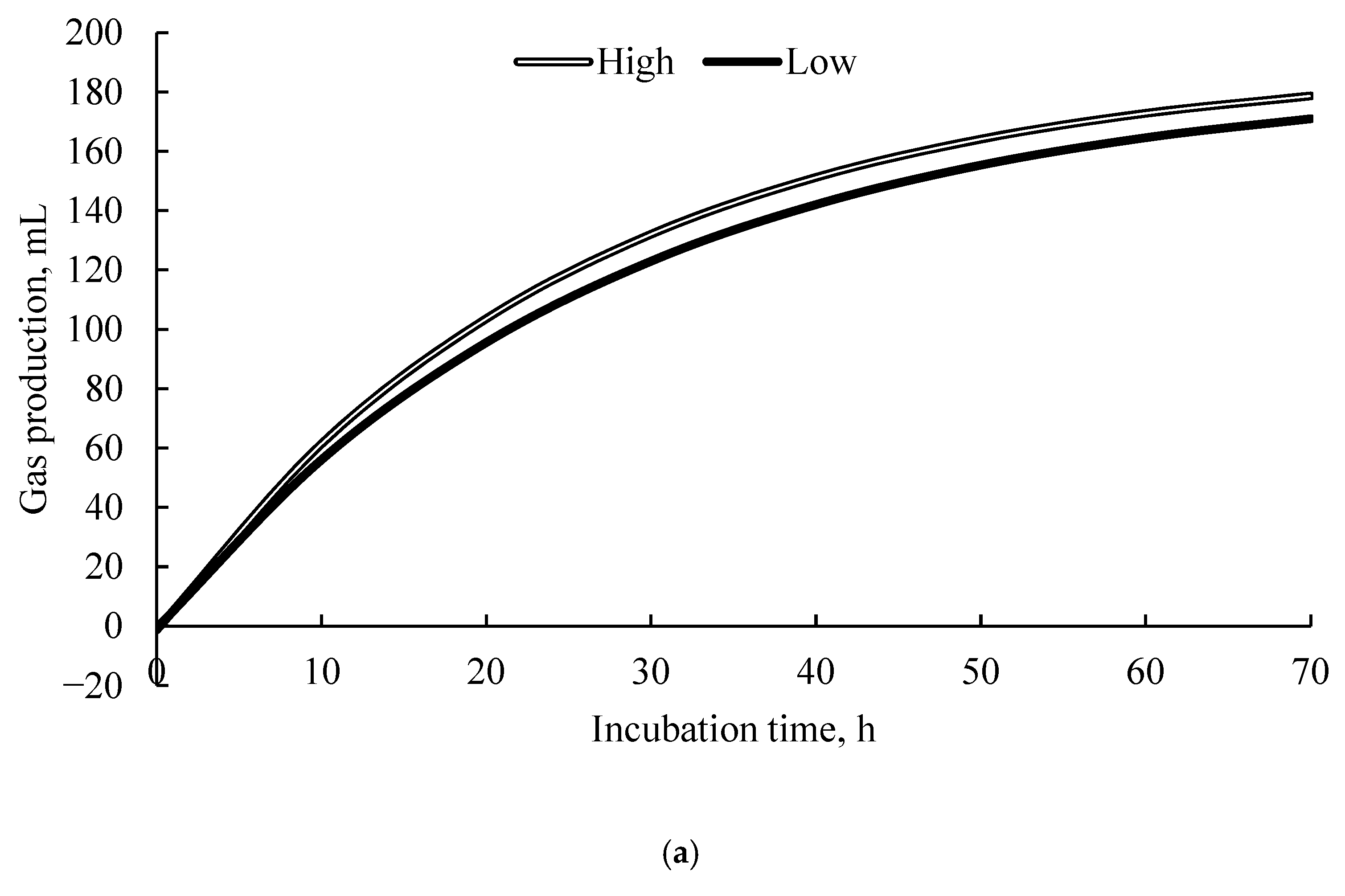

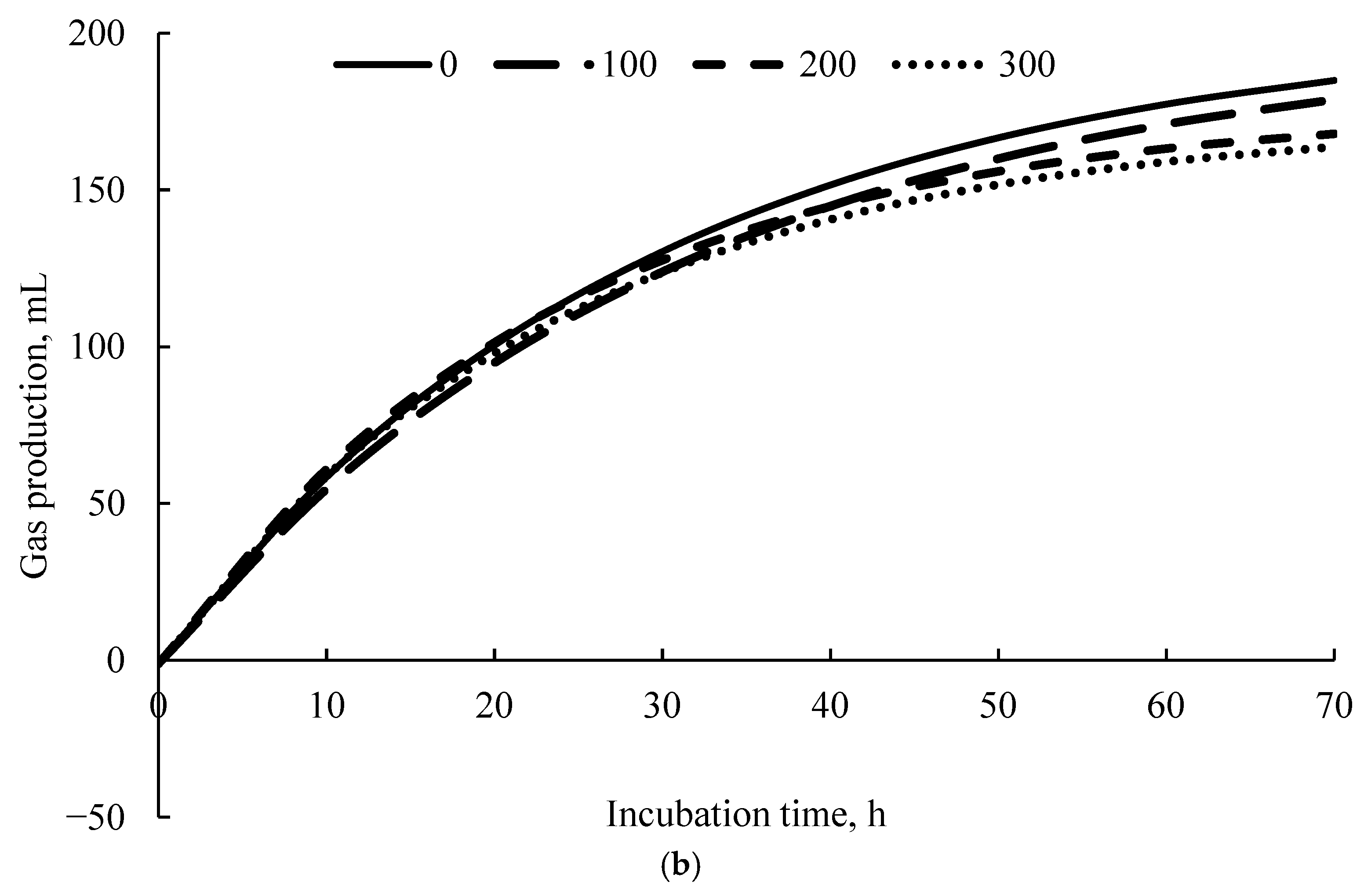

3.4. Kinetics of Gas Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olival, A.A.; Souza, S.E.X.F.; Morais, J.J.G.; Campana, M. Effect of Amazonian tree species on soil and pasture quality in silvopastoral systems. Acta Amaz. 2021, 51, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, D.C.; Hera, R.; Cairo, J.; Orta, Y. Samanea saman, árbol multipropósito con potencialidades como alimento alternativo para animales de interés productivo. Rev. Cubana Cienc. Agric. 2014, 48, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C.M.S.; Salman, A.K.D.; Oliveira, T.K. Guia Arbopasto: Manual de Identificação e Seleção de Espécies Arbóreas para Sistemas Silvipastoris; EMBRAPA: Brasília, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Staples, G.W.; Elevitch, C.R. Samanea saman (rain tree). In Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry; Elevitch, C.R., Ed.; Permanent Agriculture Resources: Holualoa, HI, USA, 2006; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, S.S.V.; Vasquez, A.T.P.; Botero, I.C.M.; Balbuena, F.J.L.; Narvaez, J.J.U.; Campos, M.R.S.; Avilés, L.R.; Sánchez, F.J.S.; Vera, J.C.K. Potential of Samanea saman pod meal for enteric methane mitigation in crossbred heifers fed low-quality tropical grass. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 258, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K. Enteric methane mitigation technologies for ruminant livestock: A synthesis of current research and future directions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 1929–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, J.R.; Laur, G.L.; Vadas, P.A.; Weiss, W.P.; Tricarico, J.M. Invited review: Enteric methane in dairy cattle production: Quantifying the opportunities and impact of reducing emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3231–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantasook, N.; Wanapat, M.; Cherdthong, A.; Gunun, P. Effect of tannins and saponins in Samanea saman on rumen environment, milk yield and milk composition in lactating dairy cows. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 99, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Kebreab, E.; Morgavi, D.P.; O’Kiely, P.; Reynolds, C.K.; Schwarm, A.; Shingfield, K.J.; Yu, Z.; et al. Design, implementation and interpretation of in vitro batch culture experiments to assess enteric methane mitigation in ruminants—A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 216, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Abdalla, A.L.; Álvarez, C.; Anuga, S.W.; Arango, J.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Becquet, P.; Berndt, A.; Burns, R.; De Camillis, C.; et al. Quantification of methane emitted by ruminants: A review of methods. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, I.C.S.; Cabral Filho, S.L.S.; Gobbo, S.P.; Louvandini, H.; Vitti, D.M.S.S.; Abdalla, A.L. Influence of inoculum source in a gas production method. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005, 123, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Bueno, I.C.S.; Nozella, E.F.; Godoy, P.B.; Cabral Filho, S.L.S.; Abdalla, A.L. The influence of headspace and inoculum dilution on in vitro ruminal methane measurements. Int. Congr. Ser. 2006, 1293, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümmel, M.; Bullerdieck, P. The need to complement in vitro gas production measurements with residue determinations from in sacco degradabilities to improve the prediction of voluntary intake of hays. Anim. Sci. 1997, 64, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, I.C.S.; Vitti, D.M.S.S.; Louvandini, H.; Abdalla, A.L.A. A new approach for in vitro bioassay to measure tannin biological effects based on a gas production technique. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 141, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkar, H.P.S. Effects and fate of tannins in ruminant animals, adaptation to tannins, and strategies to overcome detrimental effects of feeding tannin-rich feeds. Small Rumin. Res. 2003, 49, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B. Neutral Detergent-Soluble Carbohydrates: Nutritional Relevance and Analysis; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2000; 76p. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, T.R. Tropical Animal Feeding: A Manual for Research Workers; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, P.M.T.; Moreira, G.D.; Sakita, G.Z.; Natel, A.S.; Mattos, W.T.; Gimenes, F.M.A.; Gerdes, L.; McManus, C.; Abdalla, A.L.; Louvandini, H. Nutritional evaluation of the legume Macrotyloma axillare using in vitro and in vivo bioassays in sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, J.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Theodorou, M.K.; Lister, S.J.; Davies, D.R.; Isac, D. A model to interpret gas accumulation profiles associated with in vitro degradation of ruminant feeds. J. Theor. Biol. 1993, 163, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, I.C.S.; Brandi, R.A.; Fagundes, G.M.; Benetel, G.; Muir, J.P. The role of condensed tannins in the in vitro rumen fermentation kinetics in ruminant species: Feeding type involved? Animals 2020, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Saxena, J. Exploitation of dietary tannins to improve rumen metabolism and ruminant nutrition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantasook, N.; Wanapat, M.; Cherdthong, A. Manipulation of ruminal fermentation and methane production by supplementation of rain tree pod meal containing tannins and saponins in growing dairy steers. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2012, 98, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B. Rumen Microbiology and Its Role in Ruminant Nutrition; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, P.H. Influence of hydrogen on rumen methane formation and fermentation balances through microbial growth kinetics and fermentation thermodynamics. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 160, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wanapat, M. Feeding of Ruminants in the Tropicals Based on Local Feed Resources; Khon Kaen Publishing Company Ltd.: Khon Kaen, Thailand, 1999; 236p. [Google Scholar]

- Galyean, M.L.; Hubbert, M.E. Review: Traditional and alternative sources of fiber—Roughage values, effectiveness, and levels in starting and finishing diets. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2014, 30, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argôlo, L.S.; Pereira, M.L.A.; Dias, J.C.T.; Cruz, J.F.; Del Rei, A.J.; Oliveira, C.A.S. Mesquite pod meal in diets of lactating goats: Ruminal parameters and microbial efficiency synthesis. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2010, 39, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanghero, M.; Braidot, M.; Fabro, C.; Romanzin, A. A meta-analysis on the relationship between rumen fermentation parameters and protozoa counts in in vitro batch experiments. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 293, 115471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, I.C.S.; Cabral Filho, S.L.M.; Gobbo, S.P.; Costa, S.F.; Stefani, P.R.; Abdalla, A.L. Comparison of inocula from sheep and cattle for the in vitro fermentation of tropical feedstuffs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1999, 83, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, H.; Lobley, G.E. Nitrogen recycling in the ruminant: A review. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, G.; Makkar, H.P.S.; Becker, K. Tannins in tropical browses: Effects on in vitro microbial fermentation and microbial protein synthesis in media containing different amounts of nitrogen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3581–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghorn, G. Beneficial and detrimental effects of dietary condensed tannins for sustainable sheep and goat production—Progress and challenges. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 147, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | High-Energy 1 | Low Energy 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 2 | 100 2 | 200 2 | 300 2 | 0 2 | 100 2 | 200 2 | 300 2 | |

| Ingredients, g/kg DM 3 | ||||||||

| Corn silage | 460 | 370 | 280 | 190 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| BVP 4 | 0.0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 0.0 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| Cynodon hay | 30.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 500 | 400 | 300 | 200 |

| Ground corn | 241 | 248 | 255 | 262 | 252 | 214 | 176 | 138 |

| Soybean meal | 214 | 191 | 168 | 145 | 140 | 110 | 80.0 | 50.0 |

| Citric pulp | 45.0 | 30.0 | 15.0 | 0.0 | 90.0 | 80.0 | 70.0 | 60.0 |

| Soybean hulls | 0.0 | 31.0 | 62.0 | 93.0 | 0.0 | 78.0 | 156 | 234 |

| Mineral premix | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Urea | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| Chemical composition, g/kg DM | ||||||||

| Neutral detergent fiber | 347 | 347 | 347 | 347 | 488 | 488 | 488 | 488 |

| Non-fiber carbohydrates | 416 | 416 | 417 | 417 | 304 | 302 | 299 | 297 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 187 | 192 | 197 | 202 | 274 | 286 | 297 | 309 |

| Lignin | 3.1 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 6.6 |

| Crude protein | 166 | 166 | 166 | 166 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Ether extract | 30 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 32 | 28 | 25 | 22 |

| RDP 5 | 107 | 105 | 104 | 102 | 109 | 107 | 105 | 103 |

| RUP 6 | 60.0 | 61.3 | 62.7 | 64.0 | 41.0 | 43.3 | 45.7 | 48.0 |

| TDN 7 | 700 | 683 | 667 | 650 | 640 | 623 | 607 | 590 |

| Item | Diet 1 | BVP 2, g/kg DM | SEM | Probabilities 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | 0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | Diet | BVP | Lin. | Qua. | Diet × BVP | Diet × Lin. | Diet × Qua | ||

| DM 4 digestibility, g/kg | 650 | 584 | 617 | 622 | 610 | 619 | 3.56 | <0.01 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.57 | 0.7 | 0.26 |

| OM 5 digestibility, g/kg | 682 | 618 | 651 | 657 | 642 | 651 | 3.67 | <0.01 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.82 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.22 |

| Partition factor 6 | 4.09 | 3.93 | 3.89 | 4.01 | 3.96 | 4.18 | 0.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.20 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| High | 4.14 | 4.00 | 4.02 | 4.2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Low | 3.64 | 4.01 | 3.9 | 4.16 | 0.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.33 | ||||||

| GP:DOM 7, mL/g | 213 | 221 | 223 | 216 | 220 | 210 | 2.22 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.41 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.05 |

| High | 211 | 215 | 216 | 209 | 2.43 | 0.19 | 0.65 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Low | 235 | 217 | 223 | 211 | 2.43 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.41 | ||||||

| CH4:DOM 8, mL/g | 23.2 | 26.1 | 24.7 | 22.6 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.37 |

| Item | Diet 1 | BVP 2, g/kg | SEM | Probabilities 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | 0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | Diet | BVP. | Lin. | Qua. | Diet × BVP | Diet × Lin. | Diet × Qua | ||

| pH | 6.69 | 6.78 | 6.68 | 6.74 | 6.74 | 6.76 | 0.012 | <0.01 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 0.74 |

| NH3-N 4, % | 0.052 | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.0071 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.69 | <0.01 | 0.75 | <0.01 |

| High | 0.048 | 0.055 | 0.053 | 0.051 | 0.0080 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Low | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.053 | 0.057 | 0.0080 | 0.01 | 0.08 | <0.01 | ||||||

| SCFA 5, mmol/L | 176 | 162 | 173 | 174 | 166 | 165 | 1.6 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.49 |

| C2:C3 6 ratio | 0.80 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.015 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.70 |

| High | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.016 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.75 | ||||||

| Low | 0.91 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.016 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.81 | ||||||

| Isoacids, mmol/L | 4.33 | 4.12 | 4.37 | 4.48 | 4.18 | 3.87 | 0.087 | 0.07 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.08 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 0.37 |

| Substrate to gas, mg | 252 | 237 | 249 | 250 | 239 | 250 | 1.7 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.47 |

| Substrate to microbials, mg | 333 | 287 | 302 | 308 | 308 | 322 | 3.8 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.28 |

| Item | Diet 1 | BVP 2, g/kg | SEM | Probabilities 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | 0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | Diet | BVP. | Lin. | Qua. | Diet × BVP | Diet × Lin. | Diet × Qua | ||

| A 4 | 191 | 186 | 204 | 199 | 177 | 173 | 5.2 | 0.34 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.33 |

| B 5 | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.0014 | 0.12 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.82 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| C 6 | −0.018 | −0.012 | −0.022 | −0.008 | −0.017 | −0.013 | 0.0036 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.87 | 0.19 |

| L 7 | 0.164 | 0.097 | 0.115 | 0.145 | 0.137 | 0.125 | 0.0432 | 0.12 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.45 |

| µ48 8 | 157 | 147 | 157 | 154 | 150 | 147 | 2.6 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Morais, J.P.G.; Abdalla, A.L.; Olival, A.d.A.; Campana, M.; Facco, F.B.; Del Valle, T.A. Amazonian Fruit (Samanea tubulosa) in Dairy Cattle Diets: In Vitro Fermentation, Gas Production, and Digestibility. Ruminants 2025, 5, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040064

de Morais JPG, Abdalla AL, Olival AdA, Campana M, Facco FB, Del Valle TA. Amazonian Fruit (Samanea tubulosa) in Dairy Cattle Diets: In Vitro Fermentation, Gas Production, and Digestibility. Ruminants. 2025; 5(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040064

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Morais, Jozivaldo Prudêncio Gomes, Adibe Luiz Abdalla, Alexandre de Azevedo Olival, Mariana Campana, Francine Basso Facco, and Tiago Antonio Del Valle. 2025. "Amazonian Fruit (Samanea tubulosa) in Dairy Cattle Diets: In Vitro Fermentation, Gas Production, and Digestibility" Ruminants 5, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040064

APA Stylede Morais, J. P. G., Abdalla, A. L., Olival, A. d. A., Campana, M., Facco, F. B., & Del Valle, T. A. (2025). Amazonian Fruit (Samanea tubulosa) in Dairy Cattle Diets: In Vitro Fermentation, Gas Production, and Digestibility. Ruminants, 5(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040064