A Proposed Framework for Nutritional Assessment in Compromised Ruminants

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

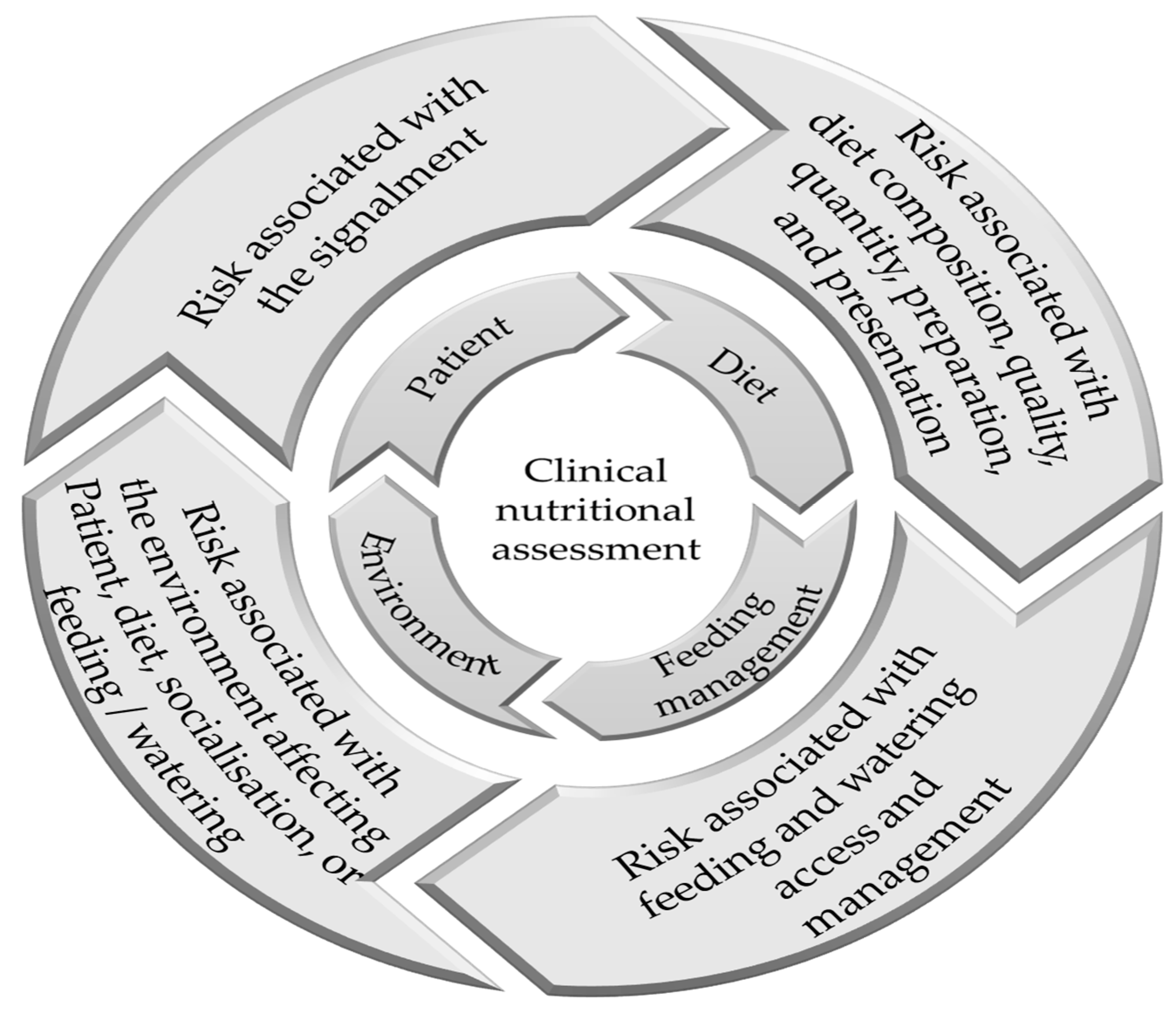

2. Nutritional Assessment Guidelines for Ruminants

- Animal-specific factors (signalment), discussed in this paper under a separate heading;

- Diet-specific factors.

- Diet-specific factors (appropriateness and safety of the diet);

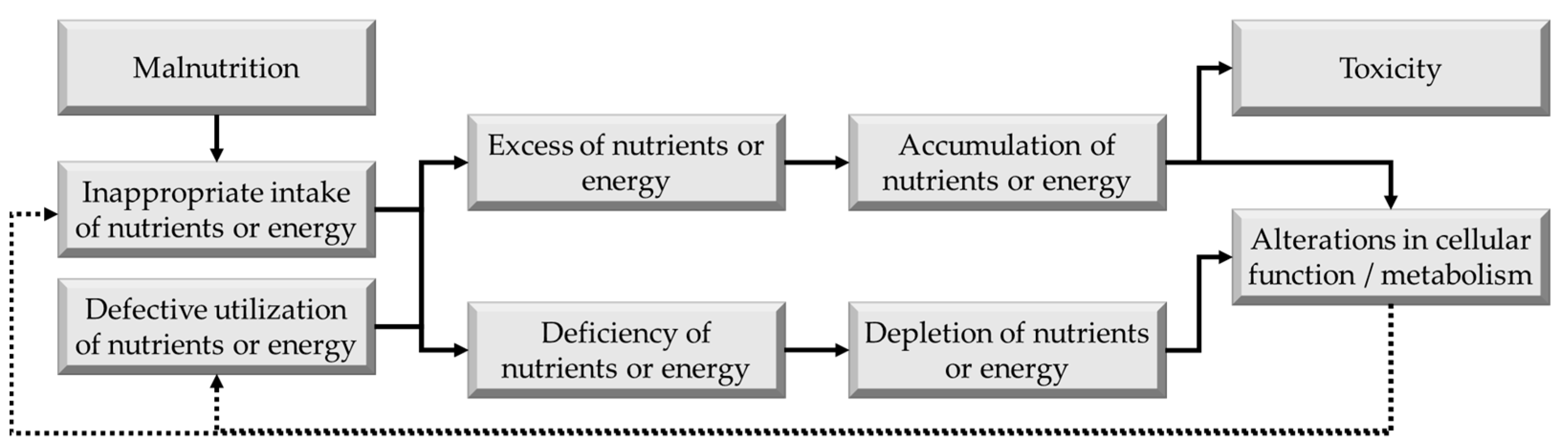

- Risk of diet-related morbidity (Figure 1);

- Feeding management and environmental factors;

- Risk of environment-related morbidity (e.g., access to the diet, competitive eating);

- Risk of feeding management morbidity (e.g., over- or underfeeding).

- Screening, every patient;

- Extended evaluation, when one or more of nutritional assessment elements during the screening process are found or suspected to have contributed to the morbidity.

2.1. Patient Signalment

- Age;

- Breed;

- Economic value;

- Identification;

- Production level;

- Production class;

- Sex;

- Species (e.g., cattle require less neutral detergent fiber (NDF) compared to sheep, and particularly goats) [30];

- Weight.

2.2. Health Interview

2.2.1. General Health Interview Enquiries Should Include the Following:

- Proportion of population affected.

- Note: May need to consider that this is the first case, and many others may occur or remain subclinical.

2.2.2. Diet-Related Enquiries Are as Follows:

- Is there a likelihood that appetite changes are due to increased intake of supplements at the detriment of the primary feedstuffs (e.g., pasture) [34]?

- This is an essential element of any nutrition assessment [21].

- Who prepares and delivers the diet, and have there been any changes?

- Details of the diet composition:

- Any known admixtures (e.g., dust, mold) [24]?

- Important to enquire as to subjectiveness in the diet assessment (e.g., weight or estimate of each diet component).

- Current and recent feeding practices [4]:

- Feeding type (e.g., bunk-fed, fed on ground, feeding rack, pasture-grazed, range-grazed):

- Any known problems (e.g., overcrowding, social interactions)?

- Current and recent grouping strategies (e.g., by age, BCS, production level, stage of reproduction) [29]:

- Is it possible that social interaction has resulted in the morbidity, or will affect the outcome of the clinical nutritional intervention?

- Calculate estimated energy and protein intake relative to current and desired BCS [4].

2.3. Examination of the Environment:

- Determine level of exposure to the elements [29] ± availability and suitability of shelter:

- May affect access and quality of the diet/drinking water [31].

- Diet/Feed residual:

- Too much (>7%) may be due to excessive offering, or inappetence to anorexia, at the population level;

- Too small (<3%) is indicative of hungry animals.

- Composition, maturity, and varieties;

- Grazing management (may need to be part of the health interview) [24];

- Topography [24];

- Note: Climate, fertilization, maturity, soil type, and time of the year significantly affect energy, fiber, mineral, protein, and vitamin content of the plants and preserved forages.

- Are concentrates fed?

- Maximum quantity may need to be considered, ensuring rumen health is not adversely affected.

- Are complete feeds provided [11]?

- The need for provision of supplements should be ensured.

- Partial/total mixed ration (partial mixed ration (PMR)/total mixed ration (TMR); when applicable).

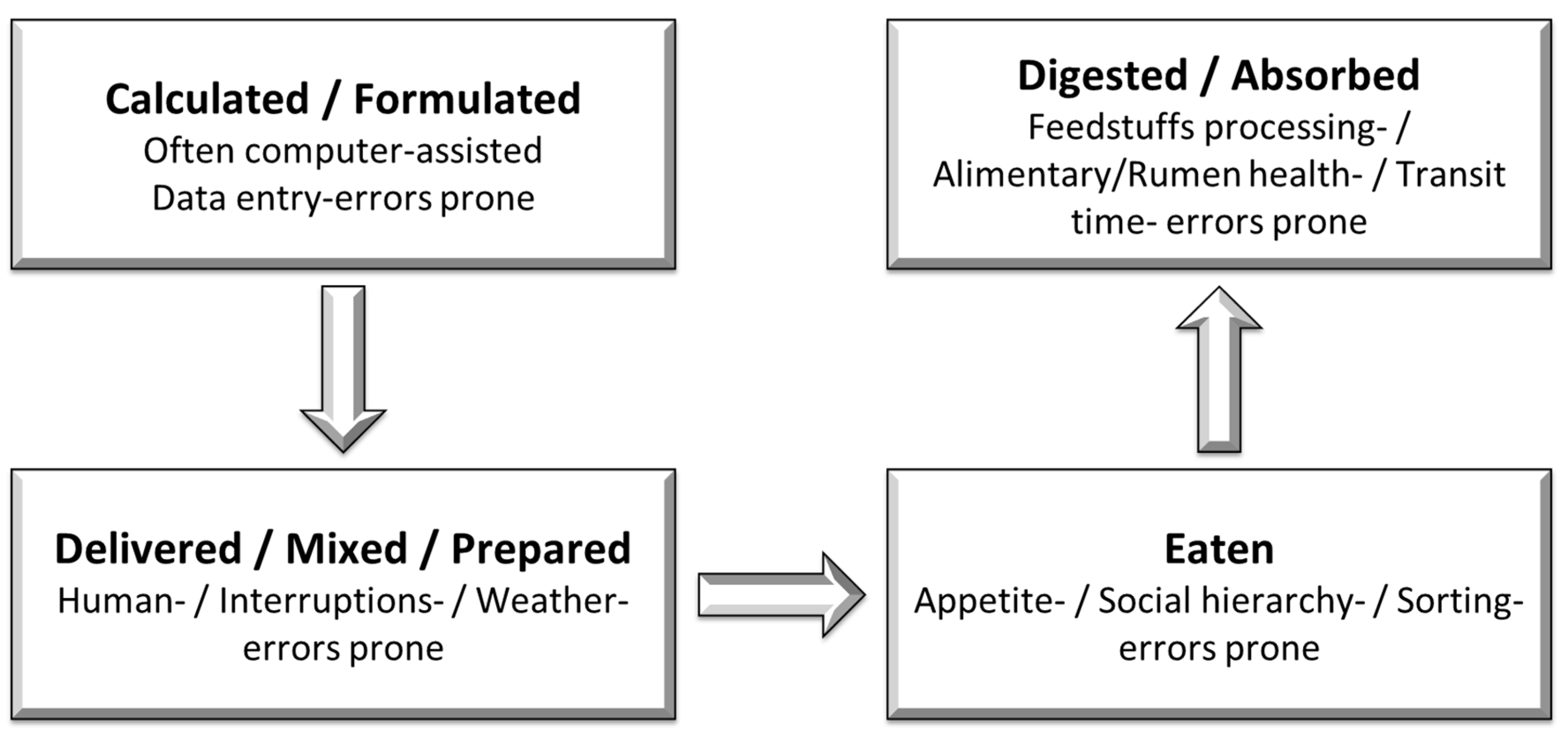

- Calculated/formulated diet:

- Look for mistakes in calculations;

- Examine possible wrong data about the composition of feedstuffs (e.g., assumptions of feedstuff composition, improper sampling technique, new batch delivered, or relying on published tables).

- Mixed/delivered diet to ruminants to eat:

- Is there an accurate weighing of feedstuffs?

- Is there a delayed delivery?

- Is there a possibility of some feedstuffs being lost after weighing (e.g., strong winds)?

- Is there too long/short mixing (allowing for sorting or provision of insufficient physically effective NDF (peNDF))?

- Eaten diet:

- Are there sufficient spaces for all animals, including the submissive, to eat simultaneously (e.g., insufficient space at the feed bunk or a too narrow strip for grazing)?

- Environmental conditions may affect DM (e.g., freezing, hot weather, rain).

- Is sorting of the diet allowed?

- Is there a coordination of the allowed access (at pasture) or delivery (at feed bunk) of the diet with the female’s return from the parlor (when applicable)?

- Is there a lack of appetite in some animals?

- Digested/absorbed:

- Is low-quality roughage fed?

- Has there been improper processing of grain?

- Consider altered function/integrity of the alimentary system.

- May affect diet access and quality;

- May affect water access.

- Nutrient analysis:

- More precise, but highly dependent on a representative sample.

- Olfactory/tactile/visual assessment:

- Color, leaf-to-stem ratio, odor/smell, uniformity;

- Evidence of spoilage;

- Presence of admixtures (any foreign material, e.g., dust, metal, plastic);

- Presence of peNDF [39]:

- May be estimated visually but also using the Penn State Forage Particle Separator.

- Nutritional biosecurity [29]:

- Accidental inclusion of carcasses (e.g., wildlife);

- Protection from vermin/wildlife.

- Nutrient storage assessment [29].

- Success of processing of feedstuffs (e.g., proportion of non-cracked grains).

- Total diet:

- Balancing/proportions;

- Preparation (e.g., over- or undermixing).

- Presence of algae in the water trough is indicative of the need for cleaning.

2.4. Nutrition-Focused Clinical Examination of the Patient

2.4.1. Examination from a Distance

- Fecal appearance, output, and evidence of presence of admixtures:

- Although presented for cattle, scores are similar for all ruminants.

- Rumination:

- At the population level, anecdotally, >60% of cows idling should be ruminating.

2.4.2. Examination from Up-Close (The Physical Examination) Investigates the Following:

- Appetite (by offering the diet in a restraining facility, particularly if not assessed during examination from a distance):

- Note that appetite may artificially change after the ruminant individual has been separated from its herd-mates.

- Note the body condition score (Table 7)/lactation status/pregnancy status (as applicable) [4,11,22,29,46]:

- Body condition score is a subjective estimate of the body fat coverage in the patient;

- May affect the time of initiation of clinical nutrition intervention;

- Over-conditioned ruminants are prone to hepatic lipidosis;

- Underconditioned ruminants with non-functional rumens require intensive care;

- Note: As changes in BCS are slow, for some patients it may be better to use body weight [29], but this may be significantly affected by the fullness of the alimentary system.

- Evidence of affected function/integrity.

- Evidence of altered elimination (e.g., constipation, diarrhea).

- Evidence of malabsorption/maldigestion syndrome.

- Patency (and if blocked, include where).

- Notes:

- In a patient with maintained gross function/integrity of the alimentary system, an oral or enteral approach to clinical nutrition intervention is recommended;

- In a patient with evidence of grossly affected function/integrity of the alimentary system, a parenteral approach to clinical nutrition intervention is recommended initially.

Table 7. Summary table for body condition scoring in cattle and buffaloes on a scale of 1 to 5. Drawings adapted from [47].Table 7. Summary table for body condition scoring in cattle and buffaloes on a scale of 1 to 5. Drawings adapted from [47].Score Description Short Ribs Spinous Processes Hook and Pin Bones Thurl Tail Head Figure Cross-section of hip bones and vertebrae Cross-section of vertebrae Cross-section of vertebrae NA Transversal section of hip to pin bone Caudal view 1 Emaciated Sharp, prominent Prominent Sharply defined Deep V-shape Very sunken 2 Thin Sharp, less prominent Less prominent Prominent V-shaped Sunken 3 Average Felt on light pressure Rounded ridge Rounded U-shaped Not sunken, but no fat deposits 4 Heavy Felt only on firm pressure Nearly flattened Smoothed over Flat with small amounts of fat deposits Not sunken, with small amounts of fat deposits 5 Fat/obese Not palpable even with firm pressure Flattened, rounded Smoothed over with obvious fat deposits Curved out Round with obvious fat deposits - Critical information on the function of the reticulorumen:

- To evaluate the forestomach function, careful auscultation and assessment of the rumen fluid are essential [22,23,41,48,49,50]:

- Note: In a patient with grossly maintained integrity but affected function, transfaunation and fluid therapy (oral or enteral) may be sufficient to ‘restart the rumen’.

- Affected function/integrity (e.g., evidence of indigestion/putrefaction):

- Including evidence of usual rumen layer stratification (dorsal-to-ventral: gas, mat, rumen liquid/slurry).

- 2.

- ii.

- See Examination from a distance.

- iii.

- Auscultation, ± palpation, and, least likely, inspection.

- iv.

- Inspection (abdominal silhouette, rumen fill score) and ± palpation.

- Critical information on the patency of various portions of the alimentary system:

- When patency is interrupted, dependent on the location of blockage, an enteral (blockage cranial to forestomaches) or parenteral (blockage caudal to forestomaches) approach to clinical nutrition intervention is recommended.

- Evidence of comorbidity.

- Likelihood of malabsorption/maldigestion syndrome [3].

- To increase absorption of nutrients, gradual diet composition approach to clinical nutrition intervention is recommended.

- Likelihood of nutrient being delivered to the intestinal mucosa [3]:

- To increase gut integrity and maintain the basic and barrier functions, oral/enteral approach to clinical nutrition intervention is recommended.

- Milk production (in lactating females) [39].

- Muscle score [29]:

- No universally accepted scoring system exists. However, the authors recommend the use of the following scoring system (Table 8). The authors have adjusted the system developed in Australia by the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries.

2.5. Laboratory Information

- Blood biochemistry:

- Acid-base balance;

- Acute phase proteins;

- Glucose levels;

- Insulin reactivity;

- Level of ROS produced:

- In high production of ROS, to minimize their negative effect, pharmaconutrients in the clinical nutrition intervention are recommended;

- Lipids content;

- Liver enzymes;

- Metabolite profiling, which is well-established for dairy cows (many others from these are mentioned in the former bullet points, e.g., ketones, NEFAs—non-esterified fatty acids);

- Mineral status (e.g., magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium for signs of refeeding syndrome).

- Hematology:

- Differential white cell counts;

- PCV (packed cell volume);

- Total protein ± various protein fractions.

- Milk quality records [39]:

- Milk:

- Fat/protein ± lactose;

- Milk urea nitrogen.

- Various metabolites (e.g., ketones, blood/serum urea nitrogen).

- Urine:

- Glucose levels;

- Protein levels.

3. Management Related to the Clinical Nutritional Intervention in Compromised Ruminants

- Establish:

- Primary concern should be addressing the primary morbidity ± comorbidities:

- Primary and supportive therapy (as required).

- Secondary concern should be given to the clinical nutritional intervention [3]:

- The need of clinical nutritional intervention;

- Nutritional requirements;

- Mode of delivery of the clinical nutritional intervention:

- How much can be provided and by which mode;

- Diet composition:

- Ensuring requirements are met for energy, fiber, minerals, protein, vitamins, and water:

- In some compromised ruminants, essential amino acids, such as lysine and methionine, should be considered, which, despite meeting total protein requirements, might induce negative effects on production and even the health status of a ruminant;

- Note: In some morbidities, clinical nutritional intervention addresses the primary morbidity (e.g., rumen acidosis/indigestion).

- Tertiary concern should be given to appropriate nursing care.

4. Monitoring of the Clinical Nutritional Intervention for Compromised Ruminants

- Frequency and type of monitoring will depend on the patient characteristics (e.g., age), primary morbidity (e.g., expected prognosis), and the mode of clinical nutritional intervention (e.g., more frequent and more laboratory-based with parenteral feeding).

- Triggers should be established that will allow for timely adjustments to be made (as required):

- Note: Introduction of clinical nutritional diet orally or enterally will need to be gradual.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Acidosis | Condition characterized by excess acids in the body fluids. |

| Anorexia | A complete absence of appetite (Synonym: aphagia). |

| Appetite | The desire to eat the offered diet. |

| Bloat | The distention of a portion of the forestomaches (i.e., rumen) resulting from the accumulation of free gas or froth (Synonym: tympany). |

| Clinical nutrition | The study and overall analysis of the interaction of nutrition and overall growth, health, and wellbeing of the (ruminant) body/individual. |

| Colostrum | The first secretion from the mammary gland after calving (giving birth), rich in antibodies, growth stimulating factors, other immune factors, and nutrients. |

| Dysphagia | Difficulty swallowing; in broader terms, it means difficulty in taking feed and/or liquids through the mouth, pharynx, and/or esophagus, therefore preventing entry into the stomach (dys-difficult + phagein-eat = difficulty eating). |

| Dysbiosis | An imbalance between the types of organism in an animal’s natural microbiota, especially that of the alimentary system, thought to contribute to a range of health effects. |

| Effective fiber (eNDF) | The fraction of fiber (NDF) that stimulates chewing activity, primarily related to the particle size (Synonym: physically effective fiber, peNDF). |

| Forage | The most important feed resource for ruminants globally. Representatives are grasses, forage crops, and legumes. May be fed as pastures or preserved forages (e.g., baleage, hay, or silage) |

| Hepatic lipidosis | A major metabolic disorder, most frequently in very late pregnancy or early lactation in female livestock, resulting from overproduction of fatty acids and accumulation of lipids within the liver (Synonym: fatty liver disease). |

| Hyperalimentation | Administration of excess nutrients by enteral/parenteral route, particularly in patients unable to ingest enough diet orally. |

| Immunocompetence | The immune system of the individual works properly and its body can mount an appropriate immune response as required. |

| Immunostimulant | A substance of natural or pharmaceutical origin that stimulates the body immune system, usually in a non-specific manner by activating or enhancing any of its components. |

| Inappetence | A decreased appetite (Synonym: hypophagia). |

| Indigestion | A disruption of the ‘normal’ function of the reticulorumen (main portion of the forestomaches in ruminants) that may affect forestomach motility and/or microbial fermentation. |

| Morbidity | Any illness in an individual. Proportion of the population affected by a particular condition/disorder/problem. State of being affected. |

| Neonate | Newborn individual. In ruminants, typically first 3–4 weeks of life before any forestomach activity is present (pre-ruminant stage). |

| Obtundancy | A dulled or reduced level of alertness or consciousness of an individual (common misnomer in veterinary medicine is depression, which is a symptom, not a sign). |

| Parenteral | Given/occurring/situated outside the intestines. |

| Patency | The quality and state of a tubular organ/system being open and the passage being uninterrupted. |

| Prebiotic | A non-digestible food ingredient that promotes the growth of beneficial gut microbiota. |

| Probiotic | Directly fed microbe which stimulates the growth of a particular enteric microbiota, especially those with beneficial properties). |

| Refeeding syndrome | A potentially fatal shift in electrolytes and fluids that may occur in severe malnourished patients receiving artificial refeeding, whether oral, enteral, or parenteral. |

| Reperfusion | The restoration of the blood flow to an organ or tissue after being significantly to completely blocked. |

| Resting energy requirement (RER) | The energy requirement of a livestock individual at rest in a thermoneutral environment. |

| Rumen | The first forestomach and the largest in a mature ruminant. It is a muscular sac that contains a large number of microbes involved in fermentation of the ingested diet. Fermented ingesta is passed into the reticulum. The fermentation of diet components unable to be digested by mammalian enzymes makes ruminants valuable in the eco system. |

| Rumen acidosis | A metabolic disease that affects all ruminants including both feedlot and dairy cattle. Rumen acidosis is usually associated with the ingestion of large amounts of highly fermentable, carbohydrate-rich feeds (e.g., cereal grains), which result in the excessive production and accumulation of acids in the rumen (pH of the rumen contents changes from mildly alkaline [around 7] to acidic [<5.6 down to <4.5]). |

| Rumenostomy | Surgical creation of temporary or permanent (insertion of rumen cannula) opening between the rumen and environment, including incising the skin, subcutaneous tissues, abdominal muscles, peritoneum, and the rumen wall. |

| Siallorrhoea | Excessive flow of saliva (‘drooling’). |

| Splanchnic | Related to organ/s within the abdominal cavity. |

| Stress | A non-specific response of the body to any demand, usually from the environment where the livestock individual resides, management, or nutrition. |

| Transfaunation | Procedure consisting of removal of rumen fluid with healthy microbiota and good quality from one ruminant, and transfer of the removed fluid into the rumen of another ruminant individual. |

References

- Freeman, L.; Becvarova, I.; Cave, N.; MacKay, C.; Nguyen, P.; Rama, B.; Takashima, G.; Tiffin, R.; Tsjimoto, H.; van Beukelen, P. WSAVA nutritional assessment guidelines. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2011, 52, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, E.A. Enteral/Parenteral nutrition in foals and adult horses Practical guidelines for the practitioner. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2018, 34, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, B.M.; Wilkins, P.A. Nutrition and the critically ill horse. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2004, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Nelson, S. Approach to clinical nutrition. UK-Vet Equine 2022, 6, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schcolnik, E. Basics of Dairy Diet Design: Feeds and How They Are Included in Diets. In Proceedings of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners Conference Proceedings, St. Louis, MO, USA, 12–13 February 2021; pp. 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, D.M.; Wall, E.H. The rumen and beyond: Nutritional physiology of the modern dairy cow. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4939–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jami, E.; Israel, A.; Kotser, A.; Mizrahi, I. Exploring the bovine rumen bacterial community from birth to adulthood. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira Rodrigues de Almeida, S.; Caetano, M.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. The Basics of Clinical Nutrition for Compromised Ruminants—A Narrative Review. Ruminants 2025, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Pathak, N.N. Clinical and Therapeutic Nutrition. In Fundamentals of Animal Nutrition; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, A. Clinical nutrition and therapeutic diets: New opportunities in farm animal practice. EC Vet. Sci. 2020, 5, 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, J.M.; Ralston, S.L. Large Animal Clinical Nutrition; Mosby Year Book: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Constable, P. Fluid and electrolyte therapy in ruminants. Vet. Clin. Food Anim. Pract. 2003, 19, 557–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, P.D.; Trefz, F.M.; Sen, I.; Berchtold, J.; Nouri, M.; Smith, G.; Grünberg, W. Intravenous and oral fluid therapy in neonatal calves with diarrhea or sepsis and in adult cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 603358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divers, T.J.; Sweeney, R.W.; Galligan, D. Parenteral nutrition in cattle. Bov. Pract. 1987, 22, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, G.; Remnant, J. Fluid therapy in calves. Practice 2016, 38, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Medicine, Division on Earth; Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council; Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Shakespeare, A.S. Rumen management during aphagia: Review article. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2008, 79, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.W.; Berchtold, J. Fluid therapy in calves. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2014, 30, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, L.T. Nutritional Management of the Sick Animal. In Proceedings of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners Conference Proceedings, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 13–16 September 1990; pp. 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, D. Practical clinical examinations of ewes and rams. Practice 2025, 47, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.; Kerby, M.; Remnant, J. Clinical examination of cattle. Part 1: Adult dairy and beef cattle. Practice 2022, 44, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radostits, O.M.; Mayhew, I.G.; Houston, D.M. Veterinary Clinical Examination and Diagnosis; Saunders: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P.G.G.; Cockcroft, P.D. Clinical Examination of Farm Animals, 1st ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger, G.; Dirksen, G.; Mack, R. Clinical Examination of Cattle, 2nd ed.; Verlag Paul Parey: Berlin, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.P.; Van Metre, D.C.; Pusterla, N. Large Animal Internal Medicine, 6th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, D.G.; Baird, A.N. Sheep and Goat Medicine, 2nd ed.; Elsevier/Saunders: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hesta, M.; Shepherd, M. How to perform a nutritional assessment in a first-line/general practice. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2021, 37, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.Q.; Südekum, K.H.; Clauss, M.; Jayanegara, A. Voluntary feed intake and digestibility of four domestic ruminant species as influenced by dietary constituents: A meta-analysis. Livest. Sci. 2014, 162, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, J.; Bosted, S. Veterinary Clinical Procedures in Large Animal Practice, 2nd ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lianou, D.T.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Michael, C.K.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Politis, A.P.; Kordalis, N.G.; Billinis, C.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Papadopoulos, E.; et al. A detailed questionnaire for the evaluation of health management in dairy sheep and goats. Animals 2020, 10, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetzel, G.R.; Berger, L.L. Protein-Energy Malnutrition in Beef Cows. In Proceedings of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners Conference Proceedings, Buffalo, NY, USA, 19–22 November 1985; pp. 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- de Aquino Monteiro, G.O.; dos Santos Difante, G.; Júnior, M.A.F.; da Silva Roberto, F.F.; Araújo, C.M.C.; da Silva, H.R.; Santana, J.C.S.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Longhini, V.Z.; Ítavo, C.C.B.F.; et al. Effects of dietary supplementation on ingestive behavior and consumption of grazing sheep: A systematic review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rharad, A.; El Aayadi, S.; Avril, C.; Souradjou, A.; Sow, F.; Camara, Y.; Hornick, J.-L.; Boukrouh, S. Meta-Analysis of Dietary Tannins in Small Ruminant Diets: Effects on Growth Performance, Serum Metabolites, Antioxidant Status, Ruminal Fermentation, Meat Quality, and Fatty Acid Profile. Animals 2025, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbuewu, I.P.; Mbajiorgu, C.A. Meta-analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on enhancement of growth performance, rumen fermentation and haemato-biochemical characteristics of growing goats. Heliyon 2023, 19, e14178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorantes-Iturbide, G.; Orzuna-Orzuna, J.F.; Lara-Bueno, A.; Mendoza-Martínez, G.D.; Miranda-Romero, L.A.; Lee-Rangel, H.A. Essential Oils as a Dietary Additive for Small Ruminants: A Meta-Analysis on Performance, Rumen Parameters, Serum Metabolites, and Product Quality. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cave, N. Nutritional Management of Gastrointestinal Diseases. In Applied Veterinary Clinical Nutrition; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 175–219. [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft, P. Bovine Medicine, 3rd ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovski, K.R.; Cusack, P.; Malmo, J.; Cockcroft, P. The value of ‘Cow Signs’ in the assessment of the quality of nutrition on dairy farms. Animals 2022, 12, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, I.J.; Golder, H.M.; Hall, M.B. Feeding, evaluating, and controlling rumen function. Vet. Clin. Food Anim. Pract. 2014, 30, 539–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, D.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xu, D.; et al. Relationship between sheep feces scores and gastrointestinal microorganisms and their effects on growth traits and blood indicators. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1348873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.W.A.; Anderson, N.; Vizard, A.L.; Anderson, G.A.; Hoste, H. Diarrhoea in Merino ewes during winter: Association with trichostrongylid larvae. Aust. Vet. J. 1994, 71, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, S.; Leonie, H.; Eva, G.; Christina, U. A Novel Chart to Score Rumen Fill Following Simple Sequential Instructions. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 82, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongini, A.; Van Saun, R.J. Pregnancy Toxemia in Sheep and Goats. Vet. Clin. N. Am.—Food Anim. Pract. 2023, 39, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Ghosh, C.P.; Datta, S. An overview of condition scoring as a management tool in goats. Indian J. Anim. Health 2022, 61, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonson, A.J.; Lean, I.J.; Weaver, L.D.; Farver, T.; Webster, G. A body condition scoring chart for Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, K.R. Assessment of the rumen fluid of a bovine patient. J. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2017, 2, 555588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.; Neidl, A.; Linhart, N.; Tichy, A.; Gasteiner, J.; Gallob, K.; Baumgartner, W.; Wittek, T. Randomised prospective study compares efficacy of five different stomach tubes for rumen fluid sampling in dairy cows. Vet. Rec. 2015, 176, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksen, G.; Smith, M.C. Acquisition and analysis of bovine rumen fluid. Bov. Pract. 1987, 22, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.S.; Rings, M.S. Current Veterinary Therapy: Food Animal Practice, 5th ed.; Elsevier—Health Sciences Division: Chantilly, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgarakis, N.; Gougoulis, D.A.; Psalla, D.; Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Katsoulis, K.; Angelidou-Tsifida, M.; Athanasiou, L.V.; Papatsiros, V.G.; Christodoulopoulos, G. Subacute rumen acidosis in Greek dairy sheep: Prevalence, impact and colorimetry management. Animals 2024, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voulgarakis, N.; Athanasiou, L.V.; Psalla, D.; Gougoulis, D.; Papatsiros, V.; Christodoulopoulos, G. Ruminal acidosis Part II: Diagnosis, prevention and treatment. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2024, 74, 6329–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | Description | Reasons and Interpretations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Creamy homogenous emulsion No visible undigested food particles Shiny surface of fresh feces | Good passage of ingesta through the alimentary system Good digestion Good food quality Good rumination Ideal score for cattle |

| 2 | Creamy homogenous emulsion A few undigested food particles of small size Shiny surface of fresh feces | Slightly impaired passage of ingesta through the alimentary system Slightly impaired digestion Less than ideal food quality Slightly impaired rumination Common in lactating and dry cows |

| 3 | Feces are not homogeneous. Some undigested particles On hand squeeze, some undigested fibers stick to the fingers Dull to shiny surface of fresh feces | Higher than normal speed of passage of the ingesta through the alimentary system Poor formation of rumen mat Poor digestion Problems with processing the grain (not broken) Acceptable score for dry cows and heifers fed on a high roughage diet due to slower passage rate |

| 4 | Bigger undigested food particles After squeezing, a ball of undigested food remains in the hand Particles sometimes >2 cm Dull surface of fresh feces | Higher than normal speed of passage of the ingesta through the alimentary system Poor formation of rumen mat Poor digestion Forages of poor quality Poor rumination Gastro-intestinal parasitism |

| 5 | Bigger food particles Undigested components of the feed ration are clearly recognizable Very dull surface of fresh feces | High speed of passage of the ingesta through the alimentary system Poor formation of rumen mat Poor digestion Forages of very poor quality Very poor rumination |

| Score | Description | Reasons and Interpretations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | After sieving, 0–25% of the original volume is left Fiber left in the sieve of short length and fluffy (<0.5 cm) | Excellent fiber digestion Ideal score |

| 2 | After sieving, 26–35% of the original volume is left Fiber left in the sieve mainly of short length (<0.5 to 1 cm) Some larger, undigested fiber particles detectable | Slightly impaired digestion Less than ideal food quality Slightly impaired rumination Common in lactating and dry cows |

| 3 | After sieving, 36–50% of original volume is left Some fiber left in the sieve >1 cm long | Poor digestion Problems with processing the grain (not broken) Poor formation of rumen mat Not acceptable for lactating cows May be acceptable for dry cows and heifers due to slower passage time |

| 4 | After sieving, 51–75% of the original volume is left Bigger undigested food particles Fiber particles sometimes >2 cm long | Poor digestion Poor formation of rumen mat Poor rumination Forages of poor quality Not acceptable for any class of dairy cattle May indicate rumen acidosis |

| 5 | Less than 10–15% reduction after sieving Bigger food particles Rough fiber particles, often >2 cm long Undigested components of the feed ration are clearly recognizable Casts of intestinal mucosa and fibrin may be present | Very poor digestion No formation of rumen mat Very poor rumination Forages of very poor quality Not acceptable for any class of dairy cattle May indicate rumen acidosis or enteritis |

| Score | Description | Reasons and Interpretations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very liquid Watery Thin Runs through fingers of a gloved hand Diarrhea Undesirable score | Various disorders of alimentary system Various generalized disorders Gastro-intestinal parasitism Excess of an osmotic gradient in the intestine Excessive readily fermentable carbohydrates Lack of fiber Some mineral excess or poisonings Moldy feed Acidosis (lighter color and low pH; usually presence of bubbles due to fermenting starch) Hindgut fermentation Very short passage time of ingesta |

| 2 | Runny, custard-like consistency Does not form a distinct pile Splatters moderately when it hits the ground Pat measures less than 2.5 cm in height More watery than optimal | Cattle on lush pasture Gastro-intestinal parasitism Excess readily fermentable carbohydrate Lack of functional fiber Excessive intake of sand/soil |

| 3 | Porridge-like appearance with several concentric rings, a small depression or dimple in the middle Makes a plopping sound when it hits concrete floors Spreads slightly on impact and settling Feces pat measures up 4 to 5 cm Sticks to the shoes | Cattle on mature pasture Optimal level of total and functional fiber |

| 4 | Thick porridge-like consistency Feces pat measures over 5 cm Original form very slightly distorted on impact and settling Firmly sticks to the shoes when touched Concentric rings evident | The level of total and functional fiber is high Low salt Low water Low protein and/or starch Adding extra grain and/or protein to the diet can decrease the score |

| 5 | Appears as firm fecal balls Original form not distorted on impact and settling Resembles horse feces Undesirable score | Excess of fiber (e.g., straw-based diet) Lack of rumen available starch Lack or rumen available protein/urea Dehydration (e.g., water deprivation) Blockage of the alimentary system |

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | No perineal fecal staining |

| 2 | Mild: Few flecks of perineal fecal staining (2–10%) |

| 3 | Moderate: Maximum up to 30% of the perineal area stained by feces (11–30%) |

| 4 | Severe: Large area of the perineal area stained with feces (31–60%) |

| 5 | Very severe: Nearly the whole perineal area stained with feces (>60%) |

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No perineal fecal staining |

| 1 | Light perineal fecal staining only around the anus |

| 2 | Mild: Perineal fecal staining around the anus and tail |

| 3 | Moderate: Perineal fecal staining around the anus, tail, and top two thirds of the thigh |

| 4 | Severe: Perineal fecal staining around the anus, tail, and the hindlimbs to the hocks |

| 5 | Very severe: Nearly the whole perineal area stained with feces |

| Score | Description | Causes and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A deep dip in the left flank More than one hand-width deep Rectangular appearance The skin under the lumbar vertebrae curves inwards The skin fold from the hook bone goes vertically downwards | Cattle have eaten little or nothing Sudden illness Insufficient food Unpalatable food Alarming situation |

| 2 | The skin under the lumbar vertebrae curves inwards for a hand-width behind the last rib Triangular appearance (referred to as ‘danger triangle’) The skin fold from the hook bone runs diagonally forward towards the last rib The paralumbar fossa behind the last rib is one hand-width deep | Common in cattle in the first week after calving In other cattle is an alarming situation May be indicative of acidosis Later in lactation sign of insufficient food intake or too-fast passage of food |

| 3 | The skin under the lumbar vertebrae goes vertically down for less than one hand-width and then curves outward The skin fold from the hook bone is not visible The paralumbar fossa behind the last rib is still just visible | Correct score for lactating cows and beef cattle on pasture Good food intake Good timing of the passage of food |

| 4 | The skin under the lumbar vertebrae curves outwards No paralumbar fossa is visible behind the last rib | Correct score for cows in late lactation Correct score for beef cattle in feedlot Correct score for early dry cows |

| 5 | The lumbar vertebrae are not visible as the rumen is very well filled The skin over the whole abdomen is quite tight No visible transition between the flank and ribs No visible transition between the flank and transverse processes | Correct score for late dry cows Correct score for heifers |

| Score | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Light muscling | Dairy type—very angular Sharp ‘tent topped’ over the top line Virtually no thickness through the stifle Stands with feet together, concave thigh |

| 2 | Moderate muscling | Narrow stance Flat to convex down the thigh Thin through the stifle Sharp, angular over the top line (except when very fat) |

| 3 | Medium muscling | Flat down thigh when viewed from behind Flat, tending to be angular over the top line |

| 4 | Heavy muscling | Thick stifle Rounded thigh viewed from behind Some convexity in the hindquarter from the side view Flat and wide over the top line—the muscle is at the same height as the backbone |

| 5 | Very heavy muscling | Extremely thick through the stifle area Muscle seams or grooves between muscles are evident ‘Apple bummed’—when viewed from the side, hindquarters bulge like an apple Butterfly top line—the loin muscles along the top of the animal are actually higher than the backbone |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrovski, K.R.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Teixeira Rodrigues de Almeida, S.; Caetano, M. A Proposed Framework for Nutritional Assessment in Compromised Ruminants. Ruminants 2025, 5, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040057

Petrovski KR, Kirkwood RN, Teixeira Rodrigues de Almeida S, Caetano M. A Proposed Framework for Nutritional Assessment in Compromised Ruminants. Ruminants. 2025; 5(4):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040057

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrovski, Kiro Risto, Roy Neville Kirkwood, Saulo Teixeira Rodrigues de Almeida, and Mariana Caetano. 2025. "A Proposed Framework for Nutritional Assessment in Compromised Ruminants" Ruminants 5, no. 4: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040057

APA StylePetrovski, K. R., Kirkwood, R. N., Teixeira Rodrigues de Almeida, S., & Caetano, M. (2025). A Proposed Framework for Nutritional Assessment in Compromised Ruminants. Ruminants, 5(4), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants5040057