Experiencing Change: Extended Realities and Empowerment in Community Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Academic Opportunities

2.1. Projecting Change 2017

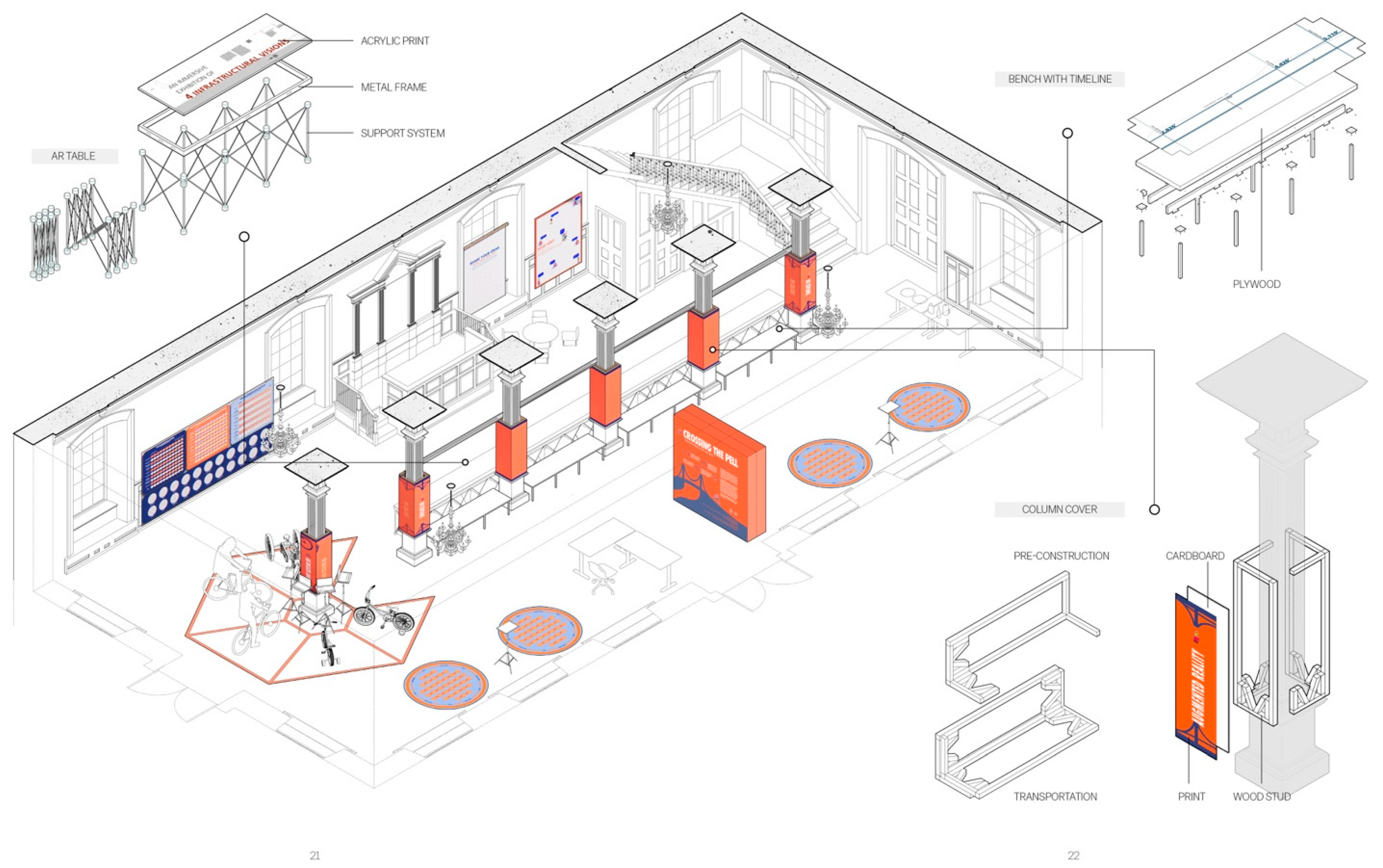

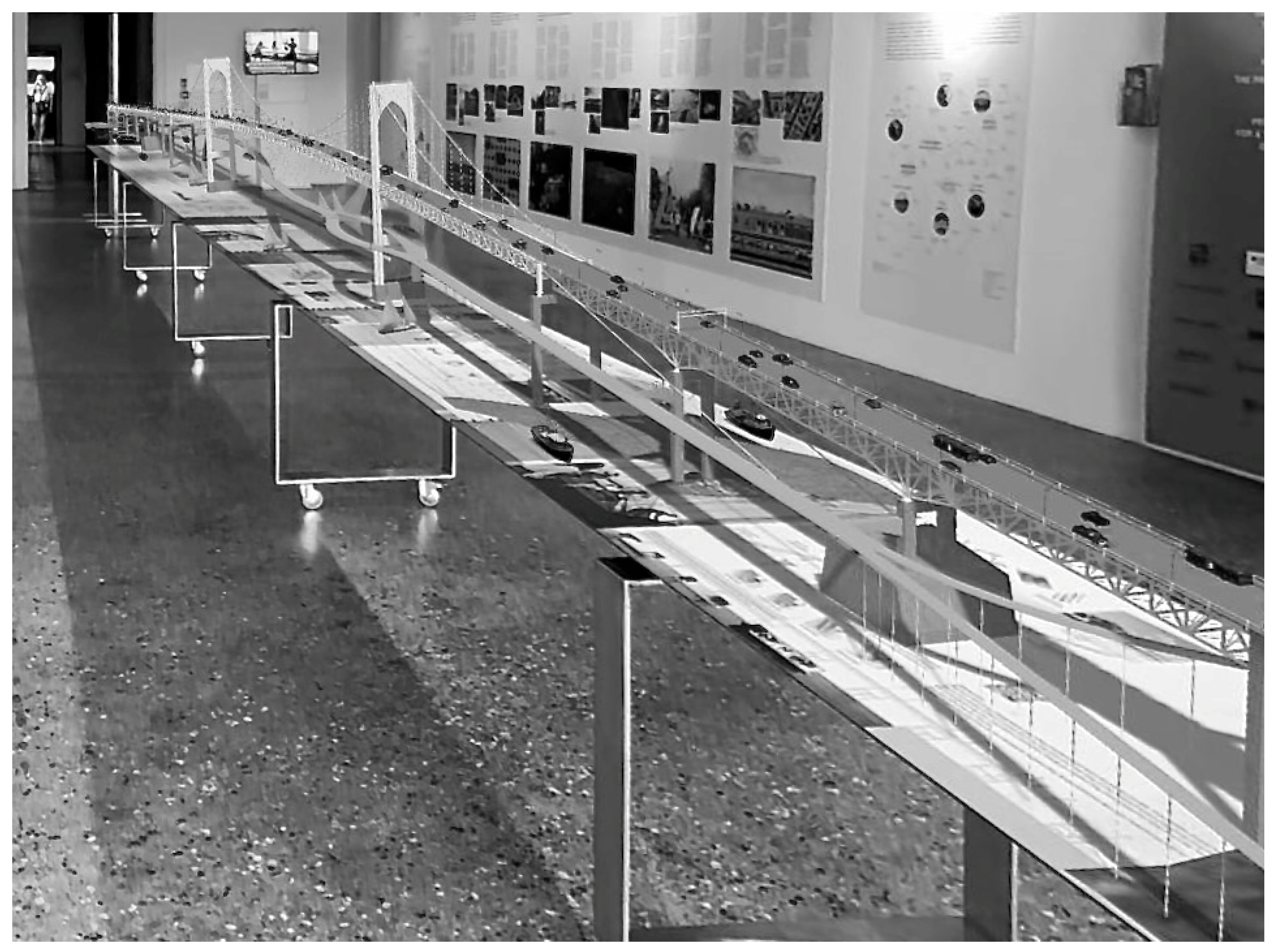

2.2. Crossing the Pell 2021–2024

3. Context: Community Engagement in the 21st Century

4. Research Objectives

- To create an exhibition on infrastructure that would be accessible to all ages and backgrounds.

- To create an exhibition that conveys four complex design proposals for adapting a 2.2 mile (3.5 km) long bridge.

- To create a system of feedback to assess the efficacy of immersive environments in engaging communities in projects of architecture and design.

5. Methodology: Design

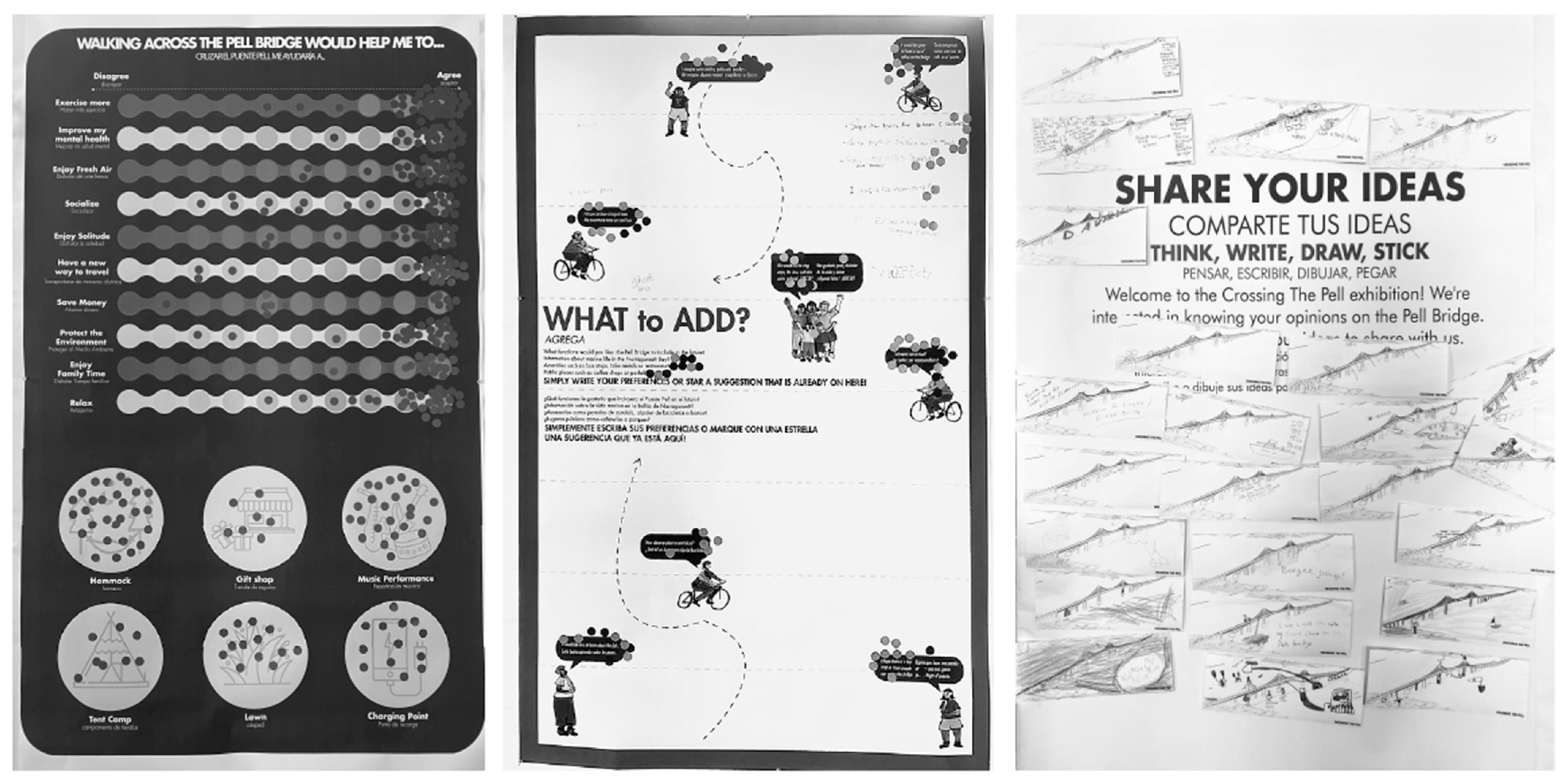

5.1. Type 1 Panels (Directed)

5.2. Type 2 Panels (Open Ended)

6. Methodology: Implementation

7. Data and Analysis

7.1. Qualitative

- Age (from conversations): The youngest visitor was three years old, she used the child bike experience. The oldest visitor was ninety-three years old and she thoroughly enjoyed the VR walking experience while her septuagenarian daughters hovered nervously by her side. There were visitors of all ages in between those two extremes.

- Gender (general observation): The audience was mixed with no discernible difference in one versus the other in any age groups.

- Ethnicity (general observation): White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, S. Asian with a majority of White visitors

- Socio-economic level (knowledge of BN)There was some indication of socio-economic levels only through the knowledge of our community partner, Bike Newport (BN). Through their advocacy for first time bikers, members of the BN team identified visitors from these neighborhoods where bike ownership was scarce. Similarly, they identified visitors who were supporters and funders of such initiatives.

- Occupation (through conversations):Occupations included the following: teacher, film maker, homemaker, construction worker, politician, museum staff, boat maker, members of the hospitality industry, graphic designer, printer, gardener, preservationist, government worker, baker, religious, lobbyist, photographer, architect, landscape architect, historian, student

7.2. Quantitative

- Number of public visitors: 492

- The number of visitors on Saturday and Sunday were accounted for visually at the entry by a BN staff member using a clicker. (Visitors to the preview were not counted.)

- Number of miles biked in total: 450 miles (725 km), each ride averaging 1.59 miles (2.5 km) (Retrieved from the computer programs connected to each bike)

- Responses to Feedback Panel Type 1: 1097 sticker responses (Table 1)

- Responses to Feedback Type 2A: 116 responses (Table 2)

- Responses to Feeback Type 2B: 24 drawings (Table 2)

- More than 500 visitors participated over three days

- The visitors reflect a makeup similar to the demographics of the city

- The visitors actively participated in the XR experiences

- Participation on the VR bike experience averaged 1.59 miles (2.5 km) per ride

- The visitors responded with feedback

- INFORMThe VR experiences offered the participant four different designs for providing bike and pedestrian access on the Pell Bridge. Without architectural drawings, the experiences conveyed extensive information on the different 2.2-mile long (3.5 km) design proposals. The AR table offered a different type of information: history and timeline of the Pell Bridge as well as contextual information of the city and the bay. The AR experience allowed the visitor to navigate the entire length for nuances of each design within a 40′ long (12.2 m) projected bridge. The I-pad permitted both overall observations and up-close interaction with the virtual bridge designs (Figure 6). All three experiences conveyed architectural information of the designs—overall strategy, siting, spatial sequences, programming and details.

- CONSULTThe Type 2A feedback panels solicited responses to questions specific to adapting the bridge for bike and pedestrian access. A total of 1097 responses were gathered. Members of the community recorded their preferences for walking and biking on the bridge through their opinion on issues both global and local. Panel Type 2B panels allowed the visitor to add observations of their own. These feedback activities were not unlike design charettes that take place in preliminary design processes for consulting with clients.

- INVOLVE, COLLABORATE AND EMPOWERThe responses to Type 2B panels offered a glimpse into the visitors’ understanding of the different schemes. Beyond the shared program of bike and pedestrian access, each project focused on its own theme: Conductivity on energy generation and public transportation, The Net on healthy aquatic ecosystems, All the World’s a Stage on tourism and performance venues and The Inhabited Bridge on outdoor urban spaces. The feedback responses for the Type 2B panels surprisingly revealed a substantial comprehension of the differences between the four schemes. While responses such as ‘ghost tour,’ ‘zip line’, ‘gondola’ or ‘bungee jumping’ may seem gratuitous, they in fact specifically relate to the adaptation of the Pell Bridge for tourism as presented in All the World’s a Stage. Responses such as “solar panel” and “wind turbines” refer directly to Conductivity where a new path not only serves non-vehicular access but also creates enough energy to power homes in the North End of Newport. Comments on the bus system and vans referred directly to a feature on the VR experience of Conductivity that shows the design of public transportation stops on the bridge. These comments exemplify an understanding of a massive design project and also its details.Type 2 Panels required the processing of information and a comprehension of the 2.2-mile long (3.5 km) designs. The comments received demonstrate the potential of community members to understand an intricate proposed design without the use of any architectural representation. This is an understanding that empowers members of the community to be collaborators.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This opportunity would extend over several academic semesters from the first advanced design studio in spring 2021 to the final installation team in Washington DC, Newport, RI and the UIA Congress in Copenhagen, DK concluding in summer 2023. The team included: Lead Faculty 2021-2024: Michael Grugl, Liliane Wong; Studio Faculty 2021: Michael Grugl, Wolfgang Rudorf, Liliane Wong; Consultant Faculty Andrew Hartness, Ben Cornelius, Tucker Houlihan; Studio Faculty 2022-23: Michael Grugl, Liliane Wong; Students 2021: Shuyi Guan, Nupoor Maduskar, Saira Nepomuceno, Seung Oh, Demilade Okunfulure, Sofia Paez, Mohan Wang, Yu Xiao; Students 2022: Chuchu Chen, Zhaoyang Cui, Yangchuang Deng, Xinzhu Huang, Jinlan Huang, Shravan Rao, Yicheng Ren, Hongli Song, Xueyun Tang, Zhijie Tang, Zefeng Wang, Xinjie Xiang, Chang Xie, George Xu; Special Guest 2022: Chance Chang; Students 2023: Zhaoyang Cui, Yangchuan Deng, Miranda Goldschmidt, Reem Habis, Rachel Strompf, Ruijie Tai, Tian Tian. |

| 2 | Crossing the Pell was funded by the Champlin Foundation, the Bafflin Foundation and the Bazarsky Family Foundation of RI. |

References

- Oladeji, S.O.; Grace, O.; Ayodeji, A.A. Community Participation in Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage Resources in Yoruba Ethnic Group of South Western Nigeria. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221130987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisić, V.; Tomka, G. Citizen Engagement & Education Learning Kit for Heritage Civil Society Organisations; Europa Nostra: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E. Whose Sense of Place? Reconciling Archaeological Perspectives with Community Values: Cultural Landscapes in England. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2005, 11, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graduate Degree Programs, Certificates and Concentrations. RISD. Available online: https://www.risd.edu/academics/graduate-study (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Wong, L. Projecting Change: Redefining Preservation in the Era of Sea Level Rise. In Design Cultures_Revolution, Cumulus Conference Proceedings Roma 2021. Volume 2. Available online: https://cumulusroma2020.org/proceedings/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Wong, L.; Wang, Y. Projecting Change—Visualization in Mitigating the Clash of Heritage Preservation and Sea Level Rise. Architect 2020, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. Projecting Change. Open Transcripts. Available online: http://opentranscripts.org/transcript/projecting-change/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- RISD Superman Project. Available online: https://savingsuperman.risd.edu/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- American Society of Civil Engineers. Report Card for Rhode Island’s Infrastructure 2020; ASCE: RI, USA, 2020; Available online: https://infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Report-2020-RI-IRC-FINAL-WEB.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- City of Newport. Keep Newport Moving: Transportation Master Plan; City of Newport: Newport, RI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rhode Island Turnpike and Bridge Authority. Newport/Pell Bridge Improving Road Safety & the Implementation of a Moveable Median Barrier; RITBA: Jamestown, RI, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.ibtta.org/sites/default/files/documents/2015/Dublin/Offenberg_Eric.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Grugl, M.; Wong, L. Crossing the Pell: Experiencing Design in the Age of Extended Realities. In Making Design Public; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Crossing the Pell. Available online: https://crossingthepell.risd.edu/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Salmela, U. The Faro Convention Action Plan Handbook 2018–2019; Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society: Faro, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage Convention’s 40th Anniversary Celebration Concludes and Launches Kyoto Vision. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/953/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Chitty, G. (Ed.) Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO World Heritage Centre—Compendium. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/compendium/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Capacity Building. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/capacity-building/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Heritage and Community Engagement: Collaboration or Contestation; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lao, T.W. Heritage Education as an Effective Approach to Enhance Community Engagement: A Model for Classifying the Level of Engagement. In Proceedings of the HERITAGE 2022—International Conference on Vernacular Heritage: Culture, People and Sustainability, Valencia, Spain, 15–17 September 2022; Universitat Politècnica de Valènci: Valencia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Historic England. Why Engage with Communities and Do It Effectively; Historic England: Swindon, UK, 2024; Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/caring-for-heritage/community-advice-hub/why-and-how-to-engage-with-communities/#93b93b87 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- International Association for Public Participation USA. IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. Available online: https://www.iap2usa.org/cvs (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Johnston, K. Community Engagement—A Relational Perspective. In Proceedings of the Australian & New Zealand Communication Association Annual Conference, Wellington, New Zealand, 9–11 July 2008; Australia and New Zealand Communication Association and La Trobe University: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frullo, N.; Mattone, M. Preservation and Redevelopment of Cultural Heritage Through Public Engagement and University Involvement. Heritage 2024, 7, 5723–5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census Reporter. Census Profile: Newport, RI. Available online: http://censusreporter.org/profiles/16000US4449960-newport-ri/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Data USA Newport County, RI. Available online: https://datausa.io/profile/geo/newport-county-ri (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Pérez Gómez, A.; Pelletier, L. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Institute of British Architects. Good Community Engagement Leads to Successful Projects. Available online: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/knowledge-landing-page/good-community-engagement-leads-to-successful-projects (accessed on 5 August 2025).

| Panel Type 1 | Subject | Topics to Rate (Number of Responses by Stickers Applied) | Amenities (Number of Responses by Stickers Applied) |

| A | “Walking the Pell Would Help Me To….” | Exercise more (42) Improve my mental health (26) Enjoy fresh air (28) Socialize (21) Enjoy solitude (20) Have a new way to travel (25) Save money (12) Protect the environment (23) Enjoy family time (17) Relax (29) | Hammock (28) Gift Shop (7) Music Performances (23) Tent Camp (8) Lawn (13) Charging Point (13) |

| B | “What Could We Do to Improve Your Biking Experience?” | Upgraded Infrastructure (23) Seating Areas (16) Bike Parking (22) Bike Lanes (32) Biking Instruction (10) Bike Rentals (16) Clear Signage (19) Safety Measures (22) Biking App (13) Ease of Access (26) | Viewing deck (23) Plants (37) Bicycle Lane (56) Snack Bar (69) Bench (16) Jogging track (9) |

| C | “Your Suggestions Matter…” | Local Economy (26) Social Equality (27) Convenient Transportation (26) Construction Expense (27) Local History (30) Sustainability (27) Views from the bridge (33) Entertainment Experience (22) Marine Ecology (31) Safety (35) | Information on the History of the Pell Bridge (13) Pet Park (17) Wheelchair rental (5) Coffee Shop (18) Book Shop (10) Storage Lockers (6) |

| Panel Type 2 | Subject | Topics Included (# of Stickers Placed) | Responses | Written Comments |

| A | What to Add? | Information on marine life (12) bus stop, bike rentals (7) restrooms (20) coffee shops (10) parks (12) benches and bike lane (12) viewing areas (10) | 108 stickers | Separate lanes for bikes and walkers Bike repair stations with tools Public Water Refills & Fountains I want a (sic) ice cream shop! EV and E-bike charging station A skate park Ghost tour Fishing |

| B | Share your ideas | NA | 24 pictures | Live entertainment with interactive history Cloud Hotel Bungee Jump Solar panels along south elevation of road bed Wind turbines (drawn suspended from road deck) Observatory (shown on top of cable stay) Gondola tram (drawn suspended below bridge deck) Zip line (drawn suspended between foundation piers) Tourism walk experience over top for sunrise/sunset Platform for bungee jumping and bridge swing VR room (drawn below bridge deck) Under detour, if terrible traffic Do this first to get people excited about being able to go across bridges without a car! No bikes get left behind unlike current #64 bus to/from NUWC from 1A Park & Ride Low cost, frequently running van service for Newport and Jamestown Bridges |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, L. Experiencing Change: Extended Realities and Empowerment in Community Engagement. Architecture 2025, 5, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040098

Wong L. Experiencing Change: Extended Realities and Empowerment in Community Engagement. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Liliane. 2025. "Experiencing Change: Extended Realities and Empowerment in Community Engagement" Architecture 5, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040098

APA StyleWong, L. (2025). Experiencing Change: Extended Realities and Empowerment in Community Engagement. Architecture, 5(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040098