Interventions in Historic Urban Sites After Earthquake Disasters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

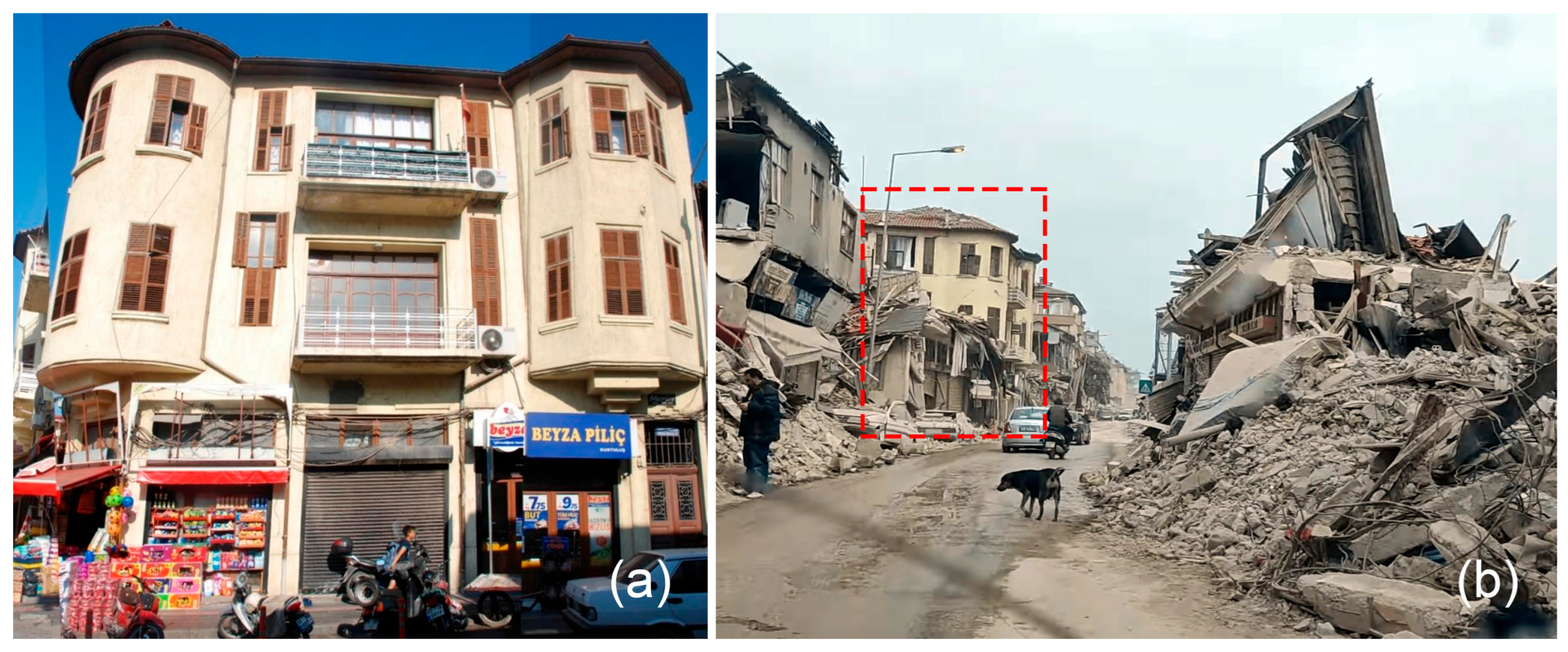

3.1. Characteristics of Case Study Sites

3.1.1. Building Periods

3.1.2. Road Network Morphology

3.1.3. Lot–Building Relationships

3.1.4. Figure–Ground

3.1.5. Land Use

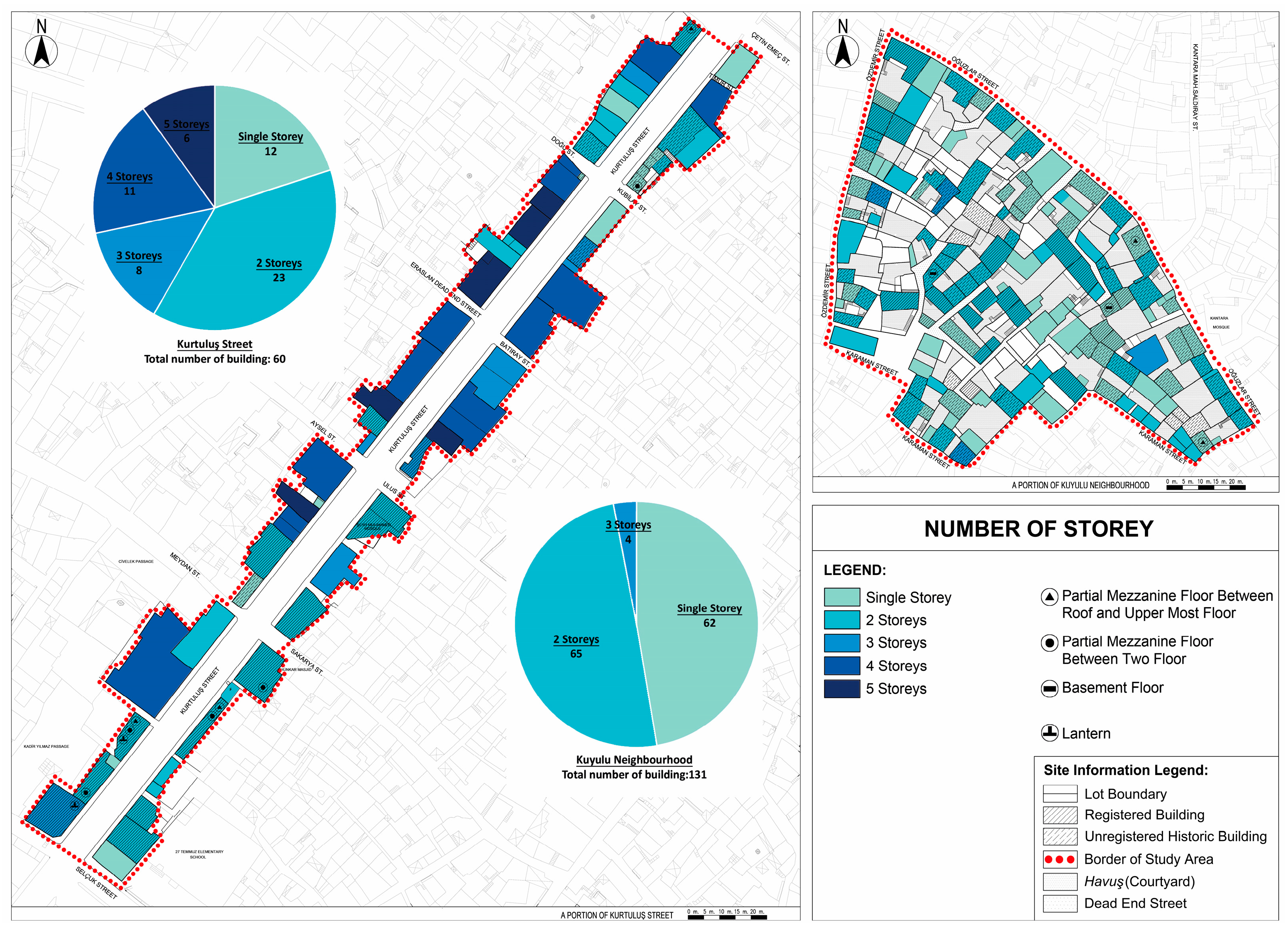

3.1.6. Number of Stories

3.1.7. Spatial Characteristics

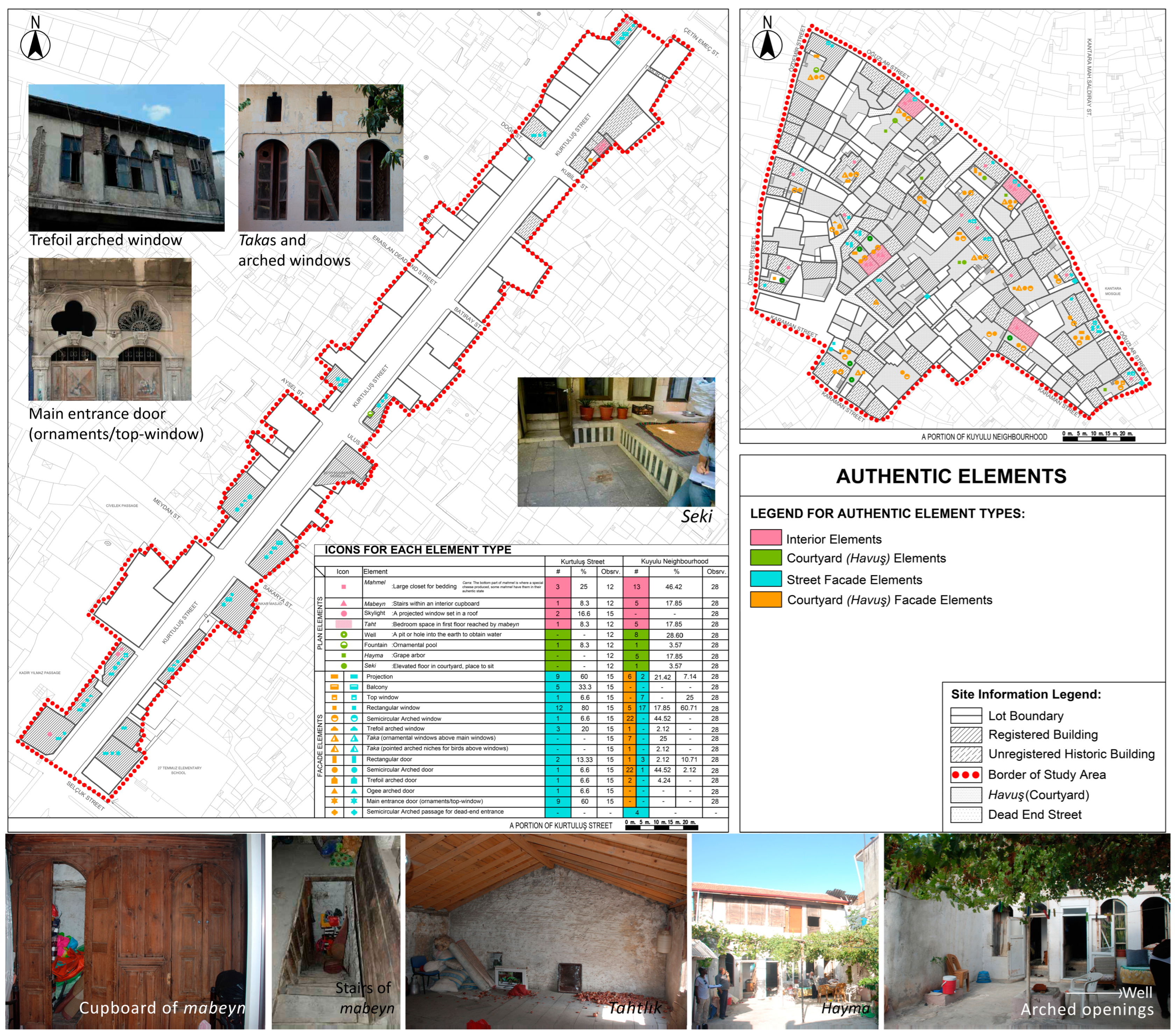

3.1.8. Authentic Elements

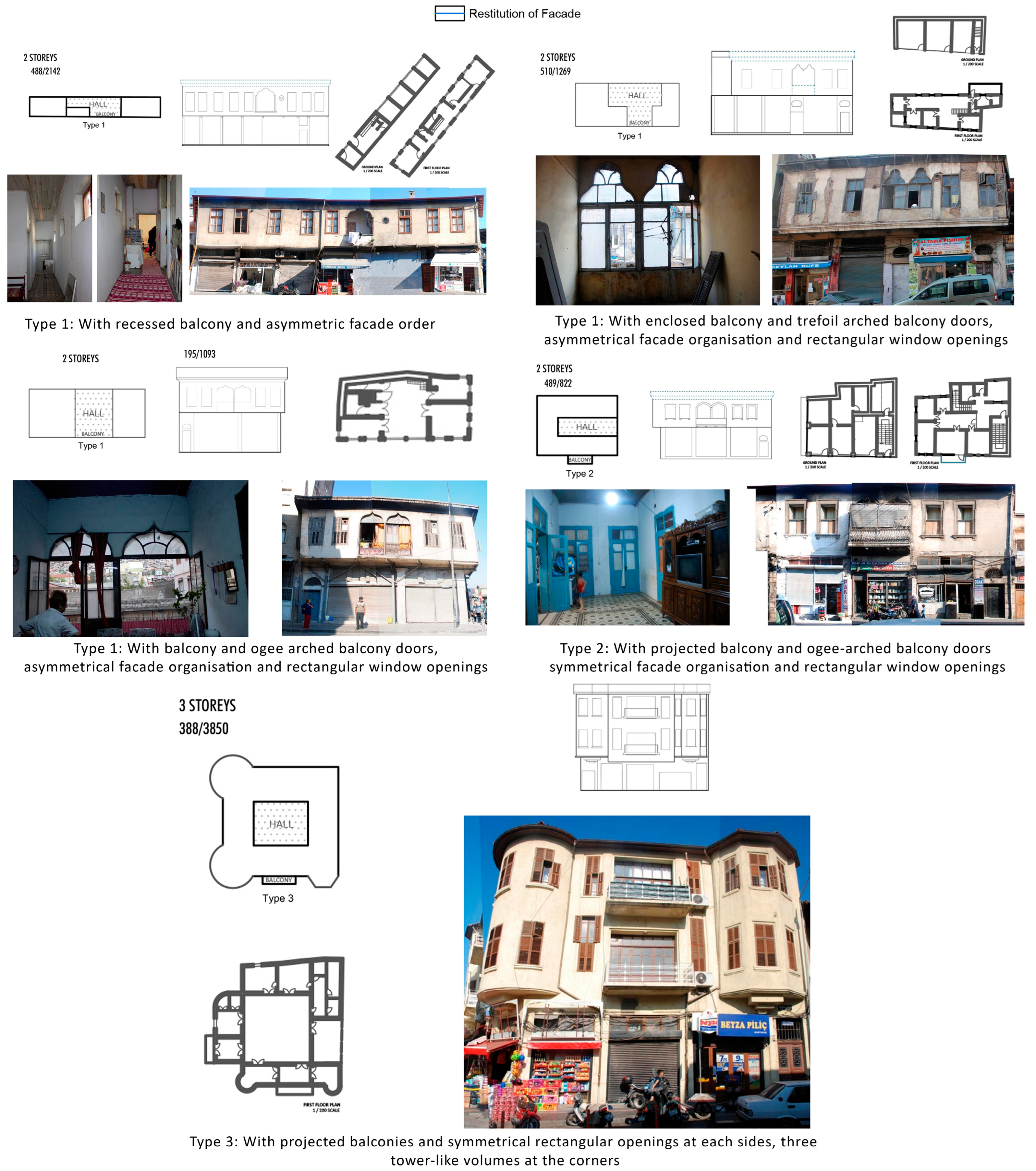

3.1.9. Housing Unit Typologies

Kuyulu Neighborhood Typologies

- The first typology was “courtyard juxtaposed at one side by main mass,” which included one- or two-story buildings, and just three of them had traces of a taka above the ground-floor windows. Its subheadings are mainly “1.1. Courtyard juxtaposed at short side by main mass,” “1.2. Courtyard juxtaposed at long side by main mass,” and “1.3. With a big squarish courtyard,” as shown in Figure 13. As a rare example of the “courtyard juxtaposed at long side by main mass” type, two examples were seen with a hayat space on the first floor. On the first floor, openings had cinquefoil arches, and they faced the hayat space, while on the ground floor, either segmental arched or rectangular openings existed. The facades had asymmetrical organization. The only example belonging to the “with a big squarish courtyard” typology had a garden wall addition separating the courtyard in the middle. Therefore, the façade of the building, which was used as a French school for a period, was also divided into two. The façade organization was symmetrical, and the ground-floor openings had ornamented taka designs above them, which differentiated the building and made it a rare example for the site.

- The second typology was “courtyard juxtaposed at two sides by masses.” In this typology, the living area and wet spaces were located in two different masses around the havuş. Its subheadings are mainly “2.1. Courtyard juxtaposed at its two opposing short sides by main masses” and “2.2. Courtyard juxtaposed at its two opposing long sides by main masses,” as shown in Figure 14. In the second sub-type, the openings as windows, takas, and doors had level differences between adjacent masses with different mass heights.

Kurtuluş Street Typologies

3.1.10. Structural System Types

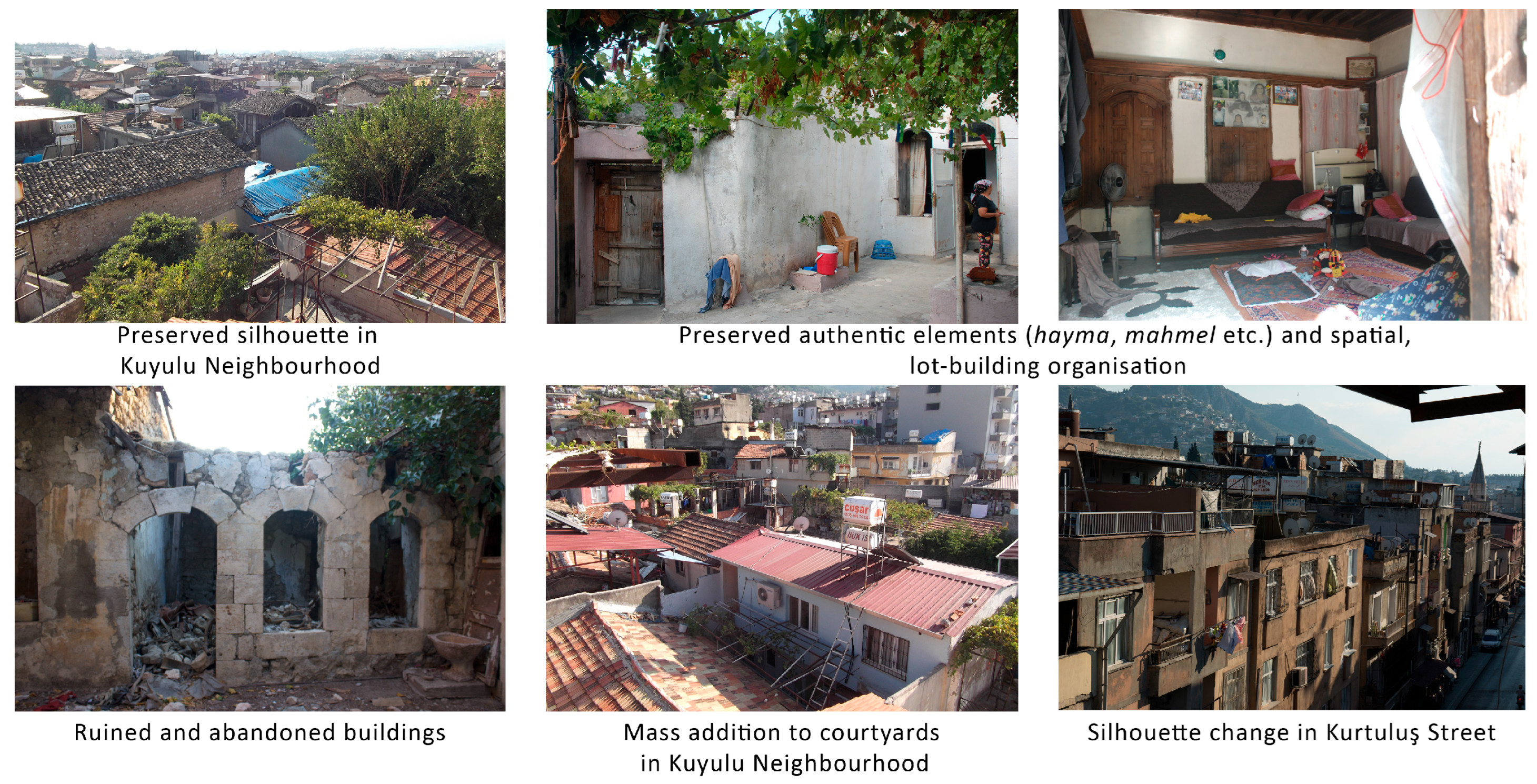

3.1.11. Conservation Conditions

3.1.12. Alterations

3.2. Values, Problems, and Potential of Sites Before and After the Earthquake

4. Discussion: Authenticity and Community-Based Strategies for Interventions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICOMOS. The Washington Charter: Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas. 1987. Available online: https://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0627717001536681570.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. Valetta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas. 2011. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Valletta-Principles-GA-_EN_FR_28_11_2011.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. European Quality Principles for Eu-Funded Interventions with Potential Impact Upon CH. 2018. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2083/6/European_Quality_Principles_2019_EN_OK.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Historic England. Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance. 2008. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-principles-sustainable-management-historic-environment/conservationprinciplespoliciesandguidanceapril08web/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on Historic Urban Landscape. 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Conservation of Cultural Property-Condition Survey and Report of Built Cultural Heritage, European Standard, EN16096. 2012. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/8f845d25-2dce-4edb-ba2a-b74a72267119/en-16096-2012?srsltid=AfmBOoq71NLyORLUv79KcM62qZVKTYegWbHBFSbleC2ANCJApsvOjOxx (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. Guidance on Post-Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties. 2017. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1763/19/ICOMOS%20Guidance%20on%20Post%20Trauma%20Recovery%20.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- UNESCO and The World Bank. Culture in City Reconstruction and Recovery. 2018. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/708271541534427317/pdf/131856-WP-REVISED-II-PUBLIC.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- ICOMOS and ICCROM. Guidance on Post-Disaster and Post-Conflict Recovery and Reconstruction for Heritage Places of Cultural Significance and World Heritage Cultural Properties. 2023. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/publications/2024-02/en_icomos-iccrom_guidance_iccrom_2024.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity. 1994. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/386-the-nara-document-on-authenticity-1994 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/about-the-centre/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/165-icomos-charter-principles-for-the-analysis-conservation-and-structural-restoration-of-architectural-heritage (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. Québec Declaration on the Preservation of the Spirit of Place. 2008. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-646-2.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance: The Burra Charter. 2013. Available online: http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. "Resilience". 2017. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/terminology/resilience (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining Urban Resilience: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Xi’an Declaration on the Conservation of the Setting of Heritage Structures, Sites and Areas. 2005. Available online: https://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0931541001587380534.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- ICOMOS. Lima Declaration for Disaster Risk Management of Cultural Heritage. 2010. Available online: https://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0621998001587380717.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Puma, P. Building Resilience: Documentating, Surveying, and Representing the Historical Urban Contexts. In Built Heritage in Post-Disaster Scenarios; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/media/16176/download?startDownload=20251014 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Piazzoni, F. What’s Wrong with Fakes? Heritage Reconstructions, Authenticity, and Democracy in Post-Disaster Recoveries. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2020, 27, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, A.; Graziosi, F.; Herrero, I.V.; Peruzzo, J.K.; de Miguel, M.L. The Dimensions of Heritage as Strategies for Action Plans for Pre and Post Disaster Intervention. In Built Heritage in Post-Disaster Scenarios; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulersoy, N.Z.; Koyunoglu, A.B. Understanding the Vulnerability of Historic Urban Sites. In International Planning History Society, Proceedings of the 17th IPHS Conference, History-Urbanism-Resilience, TU Delft, Delft, The Netherlands, 17–21 July 2016; Hein, C., Ed.; TUDelft Open: Delft, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 3, p. 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briz, E.; Garmendia, L.; Marcos, I.; Gandini, A. Improving the Resilience of Historic Areas Coping with Natural and Climate Change Hazards: Interventions Based on Multi-Criteria Methodology. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2024, 18, 1235–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandani, K.C.; Karuppannan, S.; Sivam, A. Importance of Cultural Heritage in a Post-Disaster Setting: Perspectives from the Kathmandu Valley. J. Soc. Political Sci. 2019, 2, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, D.; Forino, G.; Blaschke, T. Measuring the Progress of a Recovery Process after an Earthquake: The Case of L’aquila, Italy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Top-down Reconstruction and the Failure to “Build Back Better” Resilient Communities after Disaster: Lessons from the 2009 L’Aquila Italy Earthquake. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 29, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P.; Ninglekhu, S.; Hollenbach, P.; McCaughey, J.W.; Lallemant, D.; Horton, B.P. Rebuilding Historic Urban Neighborhoods after Disasters: Balancing Disaster Risk Reduction and Heritage Conservation after the 2015 Earthquakes in Nepal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 86, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, F.; De Falco, A.; Cutini, V. The Role of Urban Configuration during Disasters. A Scenario-Based Methodology for the Post-Earthquake Emergency Management of Italian Historic Centres. Saf. Sci. 2020, 127, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, G. Ancient Antioch; Series: Princeton Legacy Library; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Mihçioğlu Bilgi, E.; Uluca Tümer, E. Building Typologies in Between the Vernacular and the Modern: Antakya (Antioch) in the Early 20th Century. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020933318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Earth. 2025. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/antakya/@36.2001249,36.16534722,97.24557545a,2613.33051031d,35y,-0h,0t,0r/data=CiwiJgokCSD9530eOjRAER39530eOjTAGfMyB4XpFUlAIX3RWPvAyEnAQgIIAToDCgEwQgIIAEoNCP___________wEQAA (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Google Earth. 2019. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/antakya/@36.20018814,36.16558508,97.14819699a,2613.42767081d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=Cj4iJgokCSD9530eOjRAER39530eOjTAGfMyB4XpFUlAIX3RWPvAyEnAKhAIARIKMjAxOS0wNi0wMxgBQgIIAToDCgEwQgIIAEoNCP___________wEQAA?authuser=0 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- IZTECH. Conservation Project of Two Listed Urban Sites in Historic Antakya. Course: RES511 Preservation and Development Methods of Historic Environment 2019-2020 Fall, MSc Program in Architectural Restoration, Izmir Institute of Technology 2019, supervised by Prof. Dr. Mine Hamamcıoğlu-Turan, Res. Assist. Fatma Sezgi Mamaklı, Res. Assist. Keziban Çelik, and Res. Assist. Emre İpekçi. Students: Ayşe Bayram, Dilara Dikmen, Elif Çam, Hatice Ayşegül Demir, Khalid Abshir, Mine Derin Sönmez, Mukhtar Mamedov, Sait Aydınalp, Tuğçe Işık, Tuğçe Tekin.

- Tari, U.; Tüysüz, O.; Can Genç, Ş.; Imren, C.; Blackwell, B.A.B.; Lom, N.; Tekeşin, Ö.; Üsküplü, S.; Erel, L.; Altiok, S.; et al. The Geology and Morphology of the Antakya Graben between the Amik Triple Junction and the Cyprus Arc. Geodin. Acta 2013, 26, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydland, L.; Grahn, W. Identifying Heritage Values in Local Communities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredheim, L.H.; Khalaf, M. The Significance of Values: Heritage Value Typologies Re-Examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor Pérez, A.; Barreiro Martínez, D.; Parga-Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. Democratising Heritage Values: A Methodological Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altyazı Fasikül Özgür Sinema. Available online: https://fasikul.altyazi.net/pano/acinin-yerini-ofke-aldi-hesap-soracagiz/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Google Earth. 2024. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/antakya/@36.19979326,36.16604819,99.92067178a,2358.58032397d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=Cj4iJgokCSD9530eOjRAER39530eOjTAGfMyB4XpFUlAIX3RWPvAyEnAKhAIARIKMjAyNC0wMy0wMxgBQgIIAToDCgEwQgIIAEoNCP___________wEQAA?authuser=0 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Apaçık Radyo. Available online: https://apacikradyo.com.tr/kulturel-miras-ve-koruma-kim-icin-ne-icin/antakya-koruma-planlari-askida-deprem-ve-sonrasi (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Yapı Sektörünün Haber Portalı. Available online: https://www.yapi.com.tr/haberler/antakyanin-tarihi-dokusu-yok-ediliyor_211135.html (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Ripp, M.; Egusquiza, A.; Lückerath, D. Urban Heritage Resilience: An Integrated and Operationable Definition from the SHELTER and ARCH Projects. Land 2024, 13, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, A. Adaptive Reuse as a Catalyst for Post-2030 Urban Sustainability: Rethinking Industrial Heritage beyond the SDGs. Discover Sustainability. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfa, F.H.; Zijlstra, H.; Lubelli, B.; Quist, W. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings: From a Literature Review to a Model of Practice. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 13, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarza Pérez, A.J.; Verbakel, E. The Role of Adaptive Reuse in Historic Urban Landscapes towards Cities of Inclusion. The Case of Acre. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 15, 306–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Rodríguez, M.; López López, D.; Nadal, S.; Queralt, A.; Cornadó, C. Reprogramming Heritage: An Approach for the Automatization in the Adaptative Reuse of Buildings. Architecture 2024, 4, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisano, M.; Bottero, M.; Cavana, G.; Fabbrocino, F.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Fusco Girard, L. Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Built Heritage: Towards the Implementation of the Circular City Model. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1561982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehralian, H.; Chieffo, N.; Moritz, M.; Gögen, B.; Khodadadi, A.; Amaral Ferreira, M.; Oliveira, C.S. Enhancing Urban Resilience in Historical Centers: A Scenario-Based Approach to Seismic Risk and Strengthening Interventions. Disaster Prev. Resil. 2024, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.; Shen, Z. Conservation of Urban Heritage Post-Earthquake Reconstruction through Community Involvement: Case Study of THIMI-Issues and Lessons Learned. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulles, K.; Conti, I.A.M.; de Kleijn, M.B.; Kusters, B.; Rous, T.; Havinga, L.C.; Ikiz Kaya, D. Emerging Strategies for Regeneration of Historic Urban Sites: A Systematic Literature Review. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 35, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title of the Document | Identified Characteristics Giving Authenticity to a Heritage Place | Resilience Approach in Historic Urban Landscapes | Reconstruction Approach in Heritage Sites | Is There an Attempt to Direct the Pre-Disaster Documentation Process or to Benefit From It to Guide Post-Disaster Interventions in Heritage Sites? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington Charter (ICOMOS, 1987) [1] | Urban patterns (lots and streets), scale, size, style, construction, materials, color and decoration of buildings, functions | Continuous maintenance, compatible new functions and activities, careful improvement or installation of contemporary public facilities | When it is necessary to construct new buildings or adapt existing ones, the existing spatial layout should be respected, especially in terms of scale and lot size. | “Whatever the nature of a disaster affecting a historic town or urban area, preventative and repair measures must be adapted to the specific character of the properties concerned.” The expression gives importance to the specific character of the site but does not exemplify/explain the documentation process to be used in a post-disaster case. |

| Nara Document (ICOMOS, 1994) [10] | Particular forms and means of tangible and intangible expression rooted in cultures and societies: form and design, materials, use and function, traditions, setting, spirit and feeling | - | - | - |

| Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage (ICOMOS, 2003) [11] | The value of architectural heritage is not only in its appearance but also in the integrity of all its components as a unique product of the specific building technology of its time. In particular, the removal of the inner structures, maintaining only the façades, does not fit the conservation criteria. | Regular maintenance, strengthening, and monitoring is suggested for heritage buildings. | - | “Safety evaluation and an understanding of the significance of the structure should be the basis for conservation and reinforcement measures.” Without mentioning disasters, the importance of understanding the significance is stated. |

| Xi’an Declaration (ICOMOS, 2005) [16] | Beyond the physical and visual aspects, the setting includes interaction with the natural environment; past or present social or spiritual practices, customs, traditional knowledge, use, or activities; and other forms of intangible CH aspects that created and form the space, as well as the current and dynamic cultural, social, and economic context. | Monitoring should prevent or remedy decay, loss of significance, or trivialization and propose improvement in conservation management. Cooperation and engagement with associated and local communities is essential as part of developing sustainable strategies for conservation. | - | - |

| Quebec Declaration (ICOMOS, 2008) [15] | The spirit of place is made up of tangible (sites, buildings, landscapes, routes, objects) as well as intangible elements (memories, narratives, written documents, festivals, commemorations, rituals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, colors, odors, etc.). | The inhabitants and local authorities should be made aware of the safeguarding of the spirit of place so that they are better prepared to deal with the threats of a changing world. Use of modern digital technologies (digital databases, websites) can be considered to document the spirit of place. | - | - |

| Lima Declaration (ICOMOS, 2010) [17] | - | Disaster mitigation and preparedness require a comprehensive assessment of risks to the site and its occupants and visitors. Detailed rescue and response plans should also be drawn up. In historic urban areas and living cultural landscapes and their settings, identifying, assessing, and monitoring disaster risks should be carried out in collaboration with local public, governmental, and non-governmental organizations. | - | “The local authorities often demolish historic fabric after a severe earthquake. However, all cultural remains must be conserved or restored by taking into account the principles of integrity and authenticity understood in the local context.” This does not directly explain how to conserve authenticity and integrity but gives importance to it. |

| Valetta Principles (ICOMOS, 2011) [2] | Urban patterns as defined by the street grid, the lots, the green spaces, and the relationships between buildings and green and open spaces; structure, volume, style, scale, materials, color, and decoration of buildings; functions | Continuous monitoring and maintenance are essential to safeguarding a historic town or urban area effectively. | - | - |

| Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (UNESCO, 2011) [5] | The site’s topography, geomorphology, hydrology, and natural features; its built environment, both historic and contemporary; its infrastructures above and below ground; its open spaces and gardens; its land use patterns and spatial organization; perceptions and visual relationships; and all other elements of the urban structure, such as social and cultural practices and values, economic processes, and the intangible dimensions of heritage, are related to the diversity and identity of historic urban landscapes. | The historic urban landscape approach may assist in managing and mitigating impacts of sudden disasters and armed conflicts by considering ecologically sensitive policies and practices aimed at strengthening sustainability and the quality of urban life. | - | - |

| Burra Charter (ICOMOS, 2013) [13] | Cultural significance (authenticity) means aesthetic, historic, scientific, social, or spiritual value for past, present, or future generations. Cultural significance is embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places, and related objects. | Maintenance should be undertaken where fabric is of cultural significance and its maintenance is necessary to retaining that cultural significance. | The removed significant fabric should be reinstated when circumstances permit. Reconstruction is appropriate only where a place is incomplete due to damage or alteration, and only where there is sufficient evidence to reproduce an earlier state of the fabric. In some cases, reconstruction may also be appropriate as part of a use or practice that retains the cultural significance of the place. Reconstruction should be identifiable on close inspection or through additional interpretation. | - |

| Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance (Historic England 2008) [4] | Fabric, evolution of place, identified values | Regular monitoring should inform continual improvement of planned maintenance and identify the need for periodic repair or renewal at an early stage. | - | “Accessible records of the justification for decisions and the actions that follow them are crucial to maintaining a cumulative account of what has happened to a significant place, and understanding how and why its significance may have been altered.” Do not express the disaster terminology, but emphasize the use of documentation records without explaining how to apply them. |

| Conservation of cultural property—Condition survey and report of built cultural heritage (European Standard (2012) [6] | - | Maintenance: Preventive measures and simple repair can be recommended by using this standard. Other interventions cannot be recommended based on this condition survey alone. | - | - |

| Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (2015) [19] | - | Resilience is ensured by understanding disaster risk, strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk, investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience, and enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. | In the post-disaster recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction phase, it is critical to prevent the creation of disaster risk and to reduce disaster risk by “Building Back Better” and increasing public education and awareness of disaster risk. | Understanding disaster risk is possible due to the collection, analysis, management, and use of relevant data. |

| Guidance on Post-Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties (ICOMOS, 2017) [7] | Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) in world heritage sites shows the authenticity. Components of OUV: form and design; materials and substance; use and function; traditions, techniques, and management systems; location and setting; language and other forms of intangible heritage; spirit and feeling; and beliefs, stories, festivals, and rituals | Destruction impacting urban fabric may offer the opportunity to remediate problematic situations, improve living conditions, and/or improve the setting of what has survived. Articulating an approach for rebuilding urban areas requires recovering and sustaining OUV. | Reconstruction as a critical element to the maintenance of customary knowledge, practices, and beliefs, or as an opportunity to sustain these or other intangible attributes: supporting the capacity of affected communities to maintain their cultural space, activities, and values in the context of changed circumstances | “While the existence of documentation prior to disaster is fundamental for comparison, the importance of early recording of damage and surviving elements is emphasized. The priority for documentation is established on the basis of historic records and the attributes of OUV, or on the more obvious and iconic attributes, internationally or locally referred to, and how they are manifested. Image capture (such as photographs, aerial views, etc.) is a first essential step; other forms of documentation such as audio recording must be utilized as circumstances allow.” While after-disaster documentation is emphasized, the pre-disaster documentation and benefiting from it is not considered. |

| Culture in City Reconstruction (UNESCO 2018) [8] | Admits the authenticity identification of the HUL Recommendation and finds it beneficial for balanced value-giving to natural and man-made components of heritage sites | Resilience rooted in community involvement in the reconstruction process and guiding the continuity of traditions is aimed for. | Reconstruction is defined as the medium- and long-term rebuilding and sustainable restoration of resilient infrastructure, services, housing, facilities, and livelihoods required for the full functioning of a community or a society affected by a disaster. | Not the pre-disaster documentation, but the communities’ memories, containing the living record of heritage sites, are considered the key source of directing post-disaster interventions to enliven spaces related to traditions, daily life, and rituals. |

| Post-Disaster and Post-Conflict Recovery and Reconstruction for Heritage Places of Cultural Significance and World Heritage Cultural Properties (ICOMOS and ICCROM 2023) [9] | - | “Build Back Better” in the heritage context includes ensuring that the issues that led to or contributed to the loss of a heritage place in a disaster (such as poor maintenance, poor drainage, inappropriate structural interventions, inappropriate use and/or abandonment, inoperative management plans) are addressed in the recovery. | Reconstruction is one of the strategies that may be adopted to maintain or restore the physical environment during the recovery process. Achieving this will involve the maximum retention of surviving material and, in certain circumstances, may involve adding new material where necessary to maintain or recover significance. | Does not focus on pre-disaster documentation but emphasizes in-detail post-disaster documentation on sites to guide interventions |

| Authenticity Parameters in Conservation Charters, Guidelines, and Standards | Analysis Themes Based on Authenticity Parameters |

|---|---|

| Urban patterns (lots and streets), scale, size (Washington Charter, 1987) [1] Form and design, setting (Nara Document, 1994) [10] Sites, buildings, landscapes (Quebec Declaration, 2008) [12] Urban patterns as defined by the street grid, the lots, the green spaces, and the relationships between buildings and green and open spaces, volume, and scale (Valetta Principles, 2011) [2] Fabric, setting (Burra Charter, 2013) [13] Fabric (Historic England, 2008) [4] Form and design, location and setting (Guidance on Post-Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties, 2017) [7] | Road network morphology Lot-building relationships Figure–ground Number of stories |

| Style (Washington Charter, 1987; Valetta Principles, 2011) [1,2] Evolution of place (Historic England, 2008) [4] | Building periods |

| Functions (Washington Charter, 1987; Valetta Principles, 2011) [1,2] Use or activities (Xi’an Declaration, 2005) [16] Land use patterns (HUL, 2011) [5] Use (Burra Charter, 2013) [13] Use and function (Nara Document, 2004; Guidance on Post-Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties, 2017) [7,10] | Land use |

| Built environment, its open spaces and gardens, spatial organization (HUL, 2011) [5] | Spatial characteristics Housing unit typologies |

| Decoration of buildings (Washington Charter, 1987; Valetta Principles, 2011) [1,2] Traditions, spirit, and feeling (Nara Document, 2004) [10] Past or present social or spiritual practices, customs, traditional knowledge (Xi’an Declaration, 2005) [14] Social and cultural practices (HUL, 2011) [5] Rituals, traditional knowledge (Quebec Declaration, 2008) [12] Associations, meanings, records (Burra Charter, 2013) [13] Traditions, spirit and feeling, beliefs, stories, festivals, rituals (Guidance on Post-Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties, 2017) [7] | Authentic elements Socio-cultural aspects |

| Construction, materials (Washington Charter, 1987) [1] Materials (Nara Document, 2004) [10] Building technology (Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage, 2003) [11] Structure, materials (Valetta Principles, 2011) [2] Materials and substance (Guidance on Post-Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties, 2017) [7] | Structural system types |

| 7. Continuing maintenance is crucial to the effective conservation of a historic town or urban area (Washington Charter, 1987) [1]. Knowledge and understanding of the material evidence of built cultural heritage and the information on its current state is important as it helps to specify measures necessary to preserve structures in an appropriate condition and ensure that the maintenance required to keep them at this level is well defined. Preventive conservation, regular condition surveys, and maintenance is the best way to conserve and maintain the significance of built cultural heritage while ensuring that its authenticity and integrity are retained (Conservation of cultural property—Condition survey and report of built cultural heritage, European Standard, 2012) [6] Article 16. Maintenance is fundamental to conservation. Maintenance should be undertaken where fabric is of cultural significance and its maintenance is necessary to retain that cultural significance (Burra Charter, 2013) [13] | Conservation conditions |

| The basis of appropriate architectural interventions in spatial, visual, intangible, and functional terms should be respected for historical values, patterns, and layers (Valetta Principles, 2011) [2]. Article 3. Cautious approach: The traces of additions, alterations, and earlier treatments to the fabric of a place are evidence of its history and uses, which may be part of its significance. Conservation action should assist and not impede their understanding (Burra Charter, 2013) [13]. 27.2 Existing fabric, use, associations, and meanings should be adequately recorded before and after any changes are made to the place (Burra Charter, 2013) [13]. | Alterations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Demir, H.A.; Turan, M.H. Interventions in Historic Urban Sites After Earthquake Disasters. Architecture 2025, 5, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040096

Demir HA, Turan MH. Interventions in Historic Urban Sites After Earthquake Disasters. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040096

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemir, Hatice Ayşegül, and Mine Hamamcıoğlu Turan. 2025. "Interventions in Historic Urban Sites After Earthquake Disasters" Architecture 5, no. 4: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040096

APA StyleDemir, H. A., & Turan, M. H. (2025). Interventions in Historic Urban Sites After Earthquake Disasters. Architecture, 5(4), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040096