1. Introduction

This paper examines how pedagogical innovation in architecture schools can affect the city’s social spaces, land use, and understanding of local everyday practices, through architecture and design teaching. It uses selected student projects as case studies to illustrate the argument. The findings are based on two specific pedagogical formats: the ‘Architecture and Activism’ design studio at the Royal College of Art, which the author co-authored and led between 2012 and 2016, and the postgraduate program ‘Design for Cultural Commons’ at the London Metropolitan University (LMU), which the author wrote and led between 2018 and 2024. The latter was designed after analyzing the ‘Architecture and Activism’ design briefs linked to the impact of student’s work in communities. The design studio ‘Architecture and Activism’ was developed in collaboration with Andreas Lang and Francesco Sebregondi. Both formats position the postgraduate teaching environment as a Participatory Action Research (PAR) laboratory [

1,

2] in which students, communities and teachers collaborate. This challenges the mainstream teaching of architecture and urbanism, which still treats communities as abstract concepts. To clarify what is meant here by ‘abstract concept’ is that the pedagogy generalize societal behavior around the architectural project or brief rather than taking an ethnographic approach as architects. Teaching community engagement is a grounded and embodied practice. In both formats, staff-student relationships and the learning environments were conceived as spaces for exchanging knowledge and skills. Rather than providing set briefs, the pedagogy offered methodological frameworks for experimentation rather than linear knowledge transfer.

The author’s critique of the role of the professional architect in neoliberal cities, which largely perpetuates the privatization of land, is linked to the commissioning and financing of architecture by top-down and commercial powers. The pedagogical approaches described in this paper redefine the role of the architect as a practitioner, with communities and grassroots organizations acting as clients. Architectural education still deals minimally with the skills required for active engagement with communities and institutions which can be framed as a new craft. The biggest challenge of this approach is funding. However, numerous scholars are involved with the topic of grassroots economics, ranging from Gibson-Graham and Dombroski’s The Handbook on Diverse Economies [

3] to economies for the common good [

4] and various practice-based activities in credit commons [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The bottom-up role of the architect is not currently legitimized as a socio-political need and thus not funded. Teaching students to be grassroots architects without providing them with an economic arena in which to work and implement this learning is not sustainable beyond academia.

For development of module content for ‘Design for Cultural Commons’, the interdisciplinary postgraduate program that had to be invented without precedent at LMU used a wide set of theories beyond the commons that included political science, philosophy, material anthropology, organizational theory, and polycentric commons governance. However, the key theoretical concept that runs as a thread across the whole paper is the methodological theory of Participatory Action Research (PAR).

These theoretical frameworks guided the work that the students produced and how they did so, using PAR methods. PAR challenges conventional knowledge production methods by questioning how data are collected, what forms of knowledge are generated and valued, and who benefits from them. The definitions of PAR used came from Kindon et al. and Torre et al. According to them, PAR is a collaborative practice that combines research, education and action to foster social change. It involves participants from academic and non-academic contexts collaborating to address issues defined by communities. PAR is action-oriented, and its intellectual roots can be traced to Kurt Lewin’s iterative “spiral science” [

9], William Foote Whyte’s community-focused work [

10], and most notably Paulo Freire’s emancipatory pedagogy [

11], which emphasized knowledge production grounded in lived struggles. While diverse in form, PAR is consistently defined by its commitment to local engagement, mutual respect, dialogue, and inclusive knowledge production. These shared principles underpin the politics, practices, and professional identities of those engaged in PAR, which is why it was identified as relevant for the development of an architecture and activism pedagogy. However, participatory approaches, also face critique, much of it informed by post-structuralist and postcolonial thought. Critics argue that participatory methods risk being appropriated and commodified within top-down development and policy frameworks that remain essentially extractive [

1]. More severe critiques suggest that participation itself can function as a form of governance, potentially reinforcing hierarchical power relations and reproducing inequalities rather than dismantling them [

1].

These critiques were taken seriously, resulting in the adoption of commons governance systems and acknowledging that participatory approaches are not power-free or inherently emancipatory but are situated, contested, and always under evaluation. Adopting reflection ‘in’ and ‘on’ action, as conceptualized by Donald Schön [

12], enables both students and teachers to address the criticisms of a participatory approach. This approach is valuable not as an absolute solution, but as a flexible and adaptable tool for fostering social transformation, while acknowledging its limitations and the power dynamics in which the projects are embedded. Participatory research requires more than the application of participatory methods; it necessitates an epistemological and ethical shift in how knowledge is defined and how relationships with participants are structured. We can be more explicit about the cartographies of our engagements and ensure that all three elements of participation, action, and research combine productively to effect positive political change. This requires a critical and honest awareness of its challenges and dangers by recognizing the roles of power, emotions, space, and place.

The theoretical discourse on the commons that formed the basis for the development of the pedagogical design of the ‘Design for Cultural Commons’ program is shaped by the philosophical concept of distributive commons [

13]. The boundaries of distributive commons and their access regimes are co-designed with citizens. Unlike the unbounded communal commons, which assumes that citizens detached from their personal needs strive for the greater collective good, the distributive commons recognizes that individuals belong to groups with sectional interests, shaped by class, gender, and other social structures [

13]. The distributive commons concept negotiates between interests linked to personal needs of citizens, mapped against the common interests of the locality and society. They are negotiated through deliberation and relational obligations, while also incorporating inequalities in ways that benefit the least advantaged. This model critiques rationalist frameworks, such as Rawls’s difference principle [

14], for privileging abstract justice over relational and emotional dimensions of community life. Members within distributive commons engage in joint activities, democratic production and self-governance of facilities and resources [

15]. They prioritize being together rather than merely coming together for decision-making, creating political communities grounded in everyday interactions. Since Elinor Ostrom’s book on governing the commons, there has been extensive writing about the governance of such self-governing environments [

16]. The theory of distributive commons is used to describe the commons pedagogies and the conceptualization of learning commons.

The educational theories that have informed both pedagogical developments are critical pedagogy [

11], situated learning [

17], and civic education [

18,

19,

20]. These theories have been used to further develop PAR methodologies. Critical pedagogy views teaching and learning as integral to social justice, political action, and democracy, directly impacting participant engagement and enabling them to effect change in the world. Such a pedagogical approach, accompanied by action, can lead to personal and collective empowerment [

21] (pp. 24–42). Critical pedagogy advocates democratic and emancipatory teaching methods, whereas situated learning centers on the creation of communities of practice [

22] (p. 178). Conceptualization of situated learning by Lave and Wenger focuses on the quality and types of social engagements that facilitate learning [

17]. While these two theoretical frameworks consider the intimate social relationships involved in community building, civic education views the societal context as a process that influences people’s beliefs, commitments and actions. Institutions, families, friends and communities transmit civic learning without being conscious of its socializing effect [

20]. Combining these theoretical frameworks is useful for developing a pedagogy that fosters a PAR approach to architectural and design practice.

The paper describes the pedagogy and the students’ case studies of the ‘Architecture and Activism’ design studio, with all its challenges, as material and methods that resulted in the development of the pedagogy of the postgraduate program ‘Design for Cultural Commons’. This then leads to a discussion section framed as ‘learning commons’ where a proposition is made for an inclusive learning environment that sits seamlessly between the academic classroom and the city.

2. Materials and Methods

The author is framing the ‘Architecture and Activism’ pedagogy developed with Andreas Lang and Francesco Sebregondi as the PAR method that led to her developing the following interdisciplinary post graduate program ‘Design for Cultural Commons’. The former pedagogy tested the social impact of student projects in a studio for year 4 and 5 of a two-year postgraduate architecture program as action research. The following text describes the ‘Architecture and Activism’ design studio:

As architects influence major political issues such as land value and use, and the fabric of our everyday lives, their practice is social and political. Every artifact, from a mobile phone to an Olympic stadium, becomes entangled in a web of social and political relations during its production and throughout its lifespan. The shape, appearance, value and use of an artifact all directly affect the fabric of the people and things it is embedded in. These include the students as part of the network of relationships between the things being produced, the city, and its socio-political life.

The syllabus included three briefs: (1) Letter to Your Future Self, (2) Cartography of an Object, and (3) Campaigns of Disclosure.

2.1. Brief 1, Year 4 & 5: Letter to Your Future Self

Both year 4 and 5 students were asked to reflect on their personal interests, their architectural journey, and their future aspirations. PAR as an embodied methodology, requires the awareness of the self as integral to the modes of engagement students will design and implement. This enabled students to engage with who they are as citizens, architects and activists.

2.2. Brief 2, Year 5: Cartography of an Object

In the ‘Cartography of an Object’ brief, year 5 students were tasked with selecting an object that reflected their personal interests. This object did not have to be architectural. Some students chose seaweed whilst others chose their personal IP address. For a period of three months, students would closely examine the object, mapping its material composition, labor and power dynamics, manufacturing processes, environmental impact, and political directives that contributed to its existence. This brief was designed for students to understand how their own identity linked to politics, economics and systemic vulnerabilities. This offered students a critical understanding of a specific system, linked to their artifact, to help them grasp the complexity of their role within a material context.

2.3. Brief 3, Year 5: Campaigns of Disclosure

In the ‘Campaigns of Disclosure’ brief, year 5 students engaged in architectural production as a campaign. It is best to describe this brief using an example of a student’s project. Matthew Powell chose his IP address as his cartographic object in brief 2, leading to his project being about ‘commoning the Cloud’ (

Figure 1).

The project intended to raise awareness of our right to our digital data through an architectural campaign, working closely with Hack Space, a community of hackers in London. It considered how the right to manage our data and its monetization can also affect our right to control what is built in our neighborhoods. Powell’s earlier cartographies enabled him to understand intricate material and spatial configurations of the internet, both at the global and the neighborhood scale. He proposed that if each of the 20,000 residents in the neighborhood had their own servers in their gardens, capable of both heating their homes and providing internet access, the community could manage the monetization of its data as a common pool resource. Developing and employing a localized civic data infrastructure to fund a civic center was a new concept. It offered a novel method for grassroots projects to be funded (

Figure 1). Powell designed a civic building as a speculative proposition, whose aim was to manage the civic data infrastructure. As a phased process, the civic building’s public service offerings could grow, driven by increased needs and revenue from data sales. This places the community as client to fund a civic building through a digital common (

Figure 2). The civic building and its infrastructure were presented to Hack Space, who outlined the time, investment, political will, and broader interdisciplinary knowledge required to appeal to funders and policy makers. In the absence of such resources, the project was framed as a campaign. This involved creating a fake Metro newspaper and circulating photoshopped billboards on social media to highlight issues surrounding our data rights and its potential agency (

Figure 3).

Bringing such ambitious and complex projects to fruition using the PAR methodology would require students to commit to developing their projects by imagining new forms of architectural practice. However, most of them are too early in their careers and lack the skill to obtain the resources for such a task. To realize the PAR methodology’s social change priority, it is preferable to encourage students to spend more time reflecting on their impact and funding of such projects, and less time producing architectural images. To create architectural imaginaries with an activist nature, the PAR pedagogical design can fundamentally reshape the production of architecture and its role as a political tool for community campaigns.

The focus of the architectural project shifted from buildings to the funding of civic infra structure with communities as clients. Consequently, students devoted a greater proportion of their time to developing spatial cartographies, undertaking journalistic investigations, and producing architectural artifacts that would in turn give rise to novel forms of architectural practice. Here, architectural formalism and issues around architectural taste became less significant. Year 5 students refined their practice, which could place architects in a variety of work environments beyond conventional architectural firms. After graduating, a significant number of ‘Architecture and Activism’ students worked for organizations such as London Festival of Architecture, local governments, charities and think tanks. Here, they deployed their skills, strategic and complex thinking, and visual-transformation capabilities to influence socio-political policies.

2.4. Brief 2, Year 4: The Civic Classroom

For Year 4 students, the second brief, ‘The Civic Classroom’, followed their earlier brief, ‘Letter to Your Future Self’. Here, students were asked to identify areas of common interest between their personal interests identified in brief 1 and those of the communities in London Borough of Wembley. They had to engage with the local authority and community groups to negotiate these interests. To facilitate this learning experience, we took the classroom out of the institution and into the neighborhood (

Figure 4).

We were given a room-sized space by Brent council to develop a high street place making strategy. For one semester, year 4 students worked at the situated civic classroom. They became architects in residence to rigorously understand urban dynamics and test solutions unique to the locality. The concept of a researcher in residence was inspired by the work of the Artist Placement Group, which was developed in the UK in the 1960s by Ian Breakwell, Barbara Steveni, Nicholas Tresilian, John Latham and Hugh Davies [

23]. They developed residency programs for artists to be placed in institutions as critical agents. The name ‘The Civic Classroom’ was inspired by John Godard et al.’s concept of the modern civic university [

24]. He described the civic university as one that is deeply rooted in its community, balancing global research with local responsibility. By intervening in the city outside the institution, students had to engage with the city’s messy, social and political realities and learn to be agile thinkers.

However, the unpredictable, open-house nature of the space slowed down the students’ architectural productivity, which they found frustrating when speaking with colleagues in other design studios within the institution. Those students started architectural production from the first day of their studies. In the civic classroom, the development of their expertise was less about architectural form and details and more about the dynamics of the city, its needs, its emotions, and local identities and knowledge held in common [

25]. Through the agile and non-linear form of brief making in this situated pedagogical context, students learned to become empathetic designers, which challenged them to think about their agency and role as architects.

2.5. Brief 3, Year 4: The Civic Fragments

The brief ‘Civic Fragments’ tasked the students to design mobile structures that roam the city, engaging with residents who will not enter the civic classroom (

Figure 5).

These mobile structures were framed as relational architectures. They emerged from students’ personal interests linked to local narratives. Their form made them recognizable as micro-architectures in placemaking or as installations, which opened them up to various publics. As mobile structures, the ‘Civic Fragments’ acted as tools for community engagement, encouraging residents to participate playfully. As a one-to-one model, its purpose was not to represent the future form of permanent architecture, but to enable events and relationships to emerge that can inform solutions that are urban, systemic and spatial.

3. Results

The results in this paper are based on self-evaluating the ‘Architecture and Activism’ design studio syllabus, and the impact of some of the students’ work in the three years it ran. The most significant impact was the project by Tom Dobson whose work led to saving a large piece of real estate in London. This became a significant learning on author’s research focus on neighborhood commons where land is a core material. Most students described a unique, bottom-up political role of the architect in their projects that required new organizational design. This opened a new space outside the industry’s focus on form and esthetics of buildings as ultimate value.

3.1. Challenges in ‘Architecture and Activism’

A bottom-up role of the architect is not institutionally endorsed or recognized. This reframing of the role of architecture as tools to enable grassroots power was alien in an education context where buildings were designed to serve imagined and predictable social behaviors, i.e., a community kitchen is designed where the local people are supposed to cook and eat collectively without understanding of who they are and knowing about conditions in which specific communities gather. The social life of the city is messy and unpredictable, and students need time to engage with real-life situations, build trust, common ground, and encourage residents to make their voices heard. Thus, students either did not understand the architectural relevance, or they understood that engaging with complex issues in the real world has challenges. This sometimes deterred students from choosing the studio.

Pedagogies of situated learning and community engagement, when taught as a craft, can evaluate the impact that student projects have in communities. In this context, architectural assessors are often not privy to the standards by which to grade an architectural campaign, or the process of mobilizing a community to develop new forms of practice. The unlearning of architectural norms will take time. For the bottom-up role of the architect to be fully integrated into architectural education and endorsed by external regulatory bodies, educators of architecture and the built environment need to understand its value and advocate for change collectively.

Another challenge the studio faced was that architecture students who had earned degrees in architecture and design often lacked the knowledge and skills necessary for community engagement. Lack of pedagogical precedent in architecture and design education, where community engagement is not merely consultation, but rather, community development required experimentation. Hence, embracing moments of confusion and engaging in trial and error was a risk both students and teachers took. The pedagogical experiments required engagement with interdisciplinary theories in education, political science, social science and ethics.

3.2. Result: Commons Curriculum

One barrier that was identified was the disciplinary boundaries of architecture education at the time. Building on these reflections, the author proposed the interdisciplinary postgraduate design program at London Metropolitan University entitled ‘Design for Cultural Commons’. This was to test the hypothesis if architecture education was one of the barriers to impact based community projects. The new program was to explore its curriculum as a political project in a broader design discipline, using the commons discourse. It would support interdisciplinary, commons-based design practices and prepare students from all disciplines to become future changemakers. It also meant that the pedagogy and assessment criteria could be tailored to align with PAR methods, focusing on creating impact for socio-ecological practices tested in real life [

10]. Since the PAR methodology is action-centric, the quality of a project was regarded in terms of an action that is followed by a reflection on the action, leading to the design of the next action, and so forth.

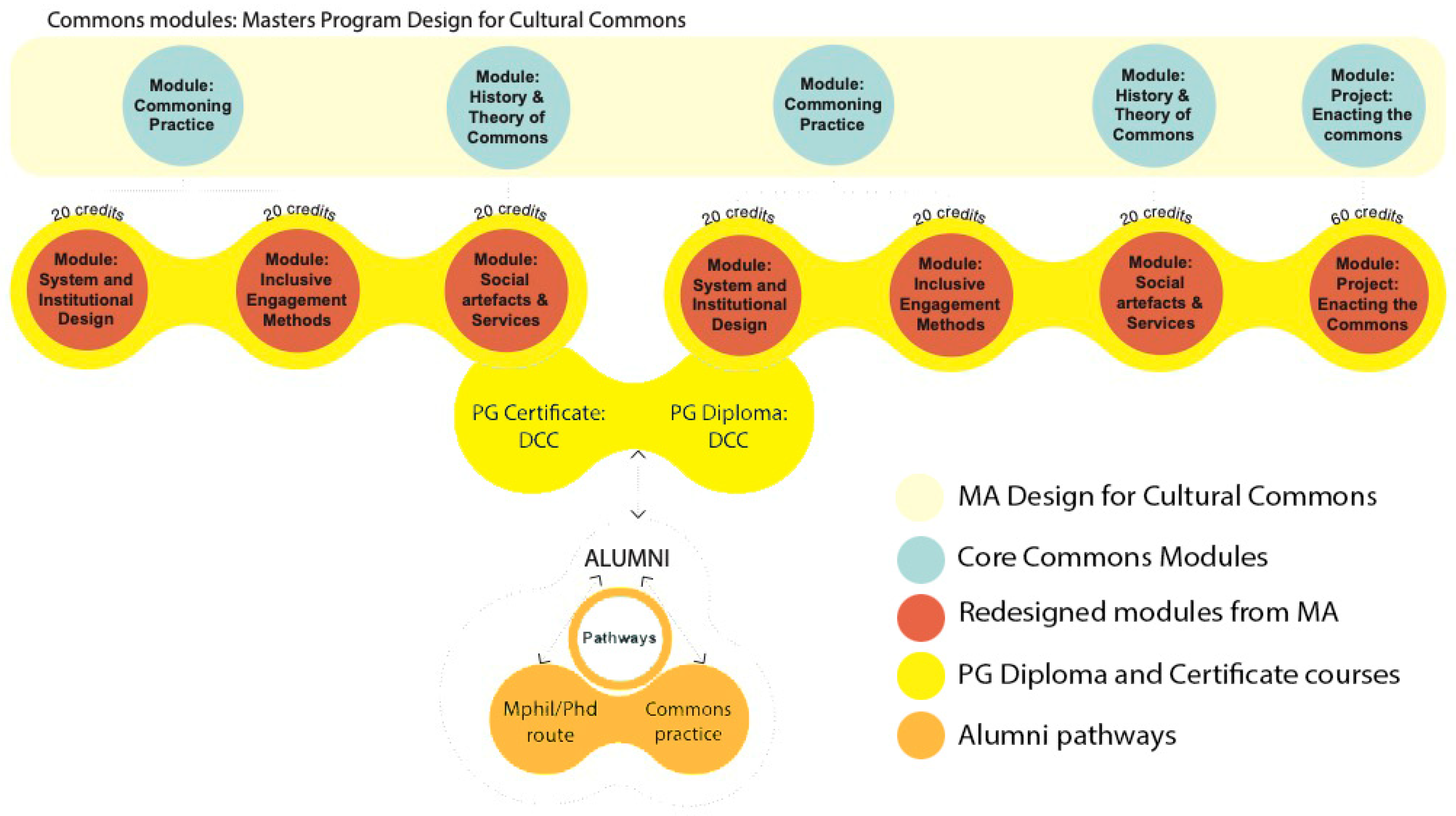

The design of the post graduate program ‘Design for Cultural Commons’ was the result of reflection on the ‘Architecture and Activism’ briefs and authors research on the commons as the third space between the private financial markets and the public state. The program content included three commons-themed modules: (1) Commoning Practice, (2) History and Theory of Commons, and (3) Project: Enacting the Commons. Other modules were borrowed from various schools at London Metropolitan University, such as the School of Social Sciences and Professions; Art, Architecture and Design; and Computing and Digital Media (

Figure 6).

The modules borrowed included social psychology, theories of citizenship, human rights and social justice, system design, comparative governance, history and theory of art, architecture and design and development of digital software applications. Workshops and discussions in the program involved how the commons can collaborate with the market and the state without being co-opted. The practice-based approach involved students developing various types of commons organization and practices that went beyond conventions, creating new forms of organizing.

Students were asked to consider questions such as whether commons practices had to intervene directly in the realm of waged work, ethical labor practices, and how waged work can be designed as an alternative to extractive systems in neoliberal capitalism. The practices and organizations the students developed always involved a specific place in the city. As the program’s content and students’ backgrounds straddled the disciplines of art, architecture, design, sociology, law and politics, the neighborhoods they engaged with offered the common ground. The program ‘Design for Cultural Commons’ is here framed as the main result of this research in deploying architectural thinking in teaching wider socially engaged design practices in the city.

The practice module focused on organizational design, drawing inspiration from the innovative architectural practices created by students as part of the ‘Architecture and Activism’ studio. The task given to the students was to design organizations that would be governed using commons principles. They would make and design products and services as collective pooled assets for the sustainability of the commons as socio-ecological enterprises. The ‘Commoning Practice’ module covered topics such as theories of power and empowerment, models of engagement, event design, collaborative governance, relational ethics of care, intellectual property, collectivism and individualism, inclusive organizational membership, interpersonal conflict resolution and social impact monitoring. Artists, architects and designers with interdisciplinary knowledge provided lectures, enabling students to develop creative approaches to tackling systemic problems. Students from disciplines such as fashion and graphic design who had never considered their role in shaping cities and engaging with communities and local government became aware of the broader impact of their field.

This module began by teaching the history and theory of the commons. However, as literature on the subject was experimental and rapidly emerging at the time, and the program aimed to invent ‘New Commons’ practices [

26], its focus shifted. Consequently, the module was renamed ‘Social Artifacts and Services’ to focus on the critical nature of artifacts as social objects within commons material systems. It also aimed at a wider audience unfamiliar with discourse of commons. The module covered theories of collective goods and commodified systems, an anthropological discourse on the materiality of artifacts, relational pictorial representation of artifacts, and esthetic theories based on relational and feminist literature [

27,

28].

The module ‘Project: Enacting the Commons’ focused on production methods for pooling common good resources and the development of practices for producing the goods and services needed by the commons’ organization. The objective of this project module was to test whether the organizations conceptualized within the ‘Commoning Practice’ module were designed to deliver commons projects. The students were tasked with broadening their disciplinary scope, moving beyond the creation of individual artifacts to more extensive systems and networks.

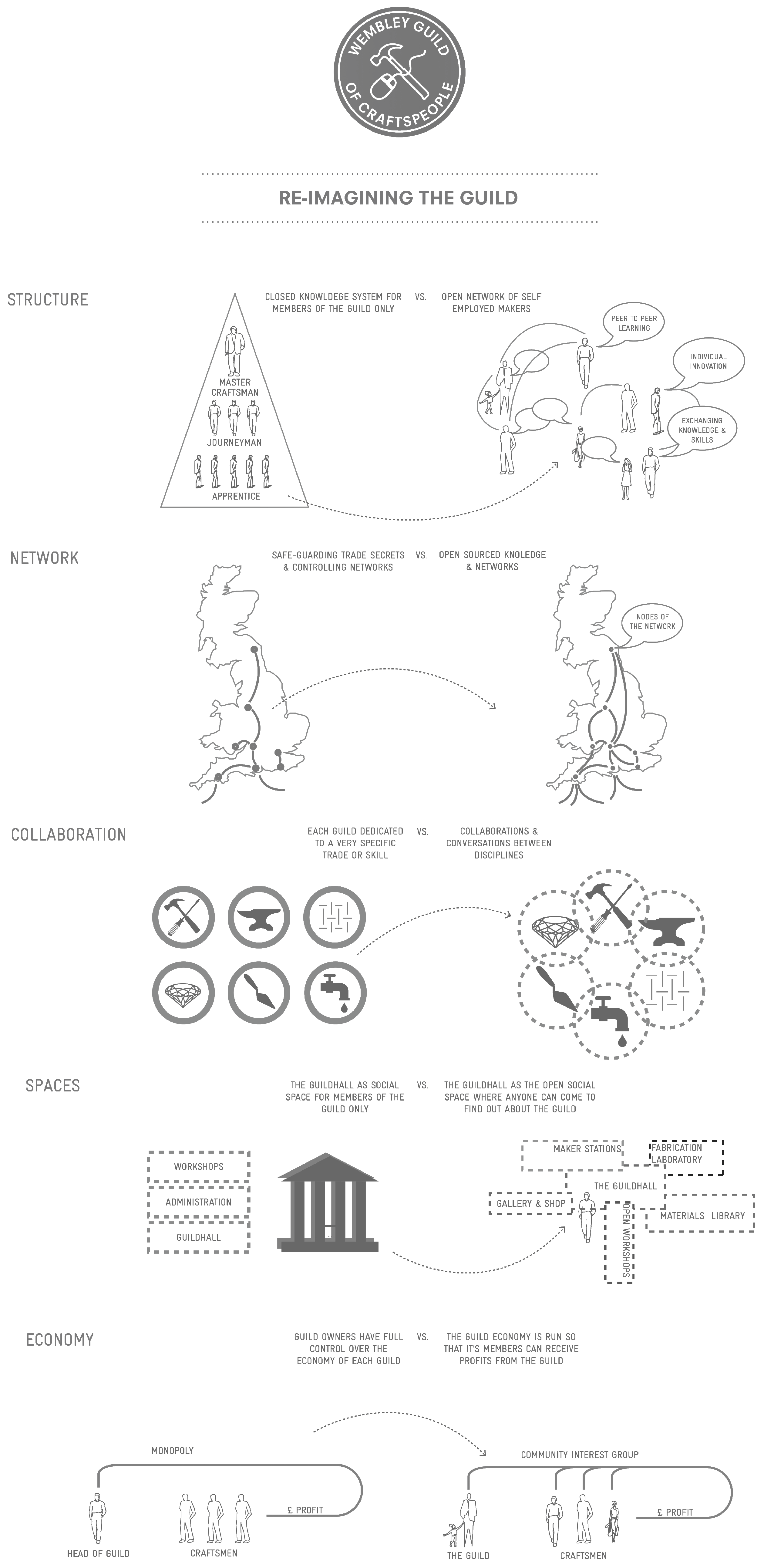

In all the modules, teaching was delivered in the form of one-hour lectures introducing students to specific topics, followed by two-hour workshops where students developed their own practice or project applying the knowledge from the lectures. In the second part of the class, students were the experts as they knew more about their project through the lens of their discipline than the teachers. This created an environment of mutual learning within the classroom. It soon became clear that the students interested in this program were mid-career professionals who either wanted to change careers or extend their work to address social issues. This also posed a challenge as professional and mature students are time-poor in cities like London. Financial constraints meant that students had to finish their studies as quickly as possible, which added to the problem of time scarcity to develop their commons organizations. This led to the creation of the concept of a Cultural Commons Guild (

Figure 7), which could provide a space for alumni to develop projects as a community of practice and enable teachers and students to continue their collaboration beyond the program.

Each module in the course was connected to an institutional partner. The ‘Commoning Practice’ module was linked to the Design Museum in London, while the ‘Enacting the Commons’ module was linked to Tate Modern’s Tate Exchange program. The ‘History and Theory of the Commons’ module was linked to London Metropolitan University’s public program, ‘The Commons’, in which students presented their projects and invited guests who spoke about the commons. The aim was to connect students with these institutions and encourage dialogue between them. The hope was that the partners would become part of the community of learners, but the emerging, unestablished nature of the commons discourse and lack of funding meant that interest waned.

4. Discussion

Based on both pedagogical designs that ran between 2012 and 2024 and the obstacles and challenges encountered, it transpired that pedagogical innovation that goes beyond institutional norms are difficult to embed within current higher educational institutions. This is because their legitimacy relies on upholding societal norms and expectations, as well as familiar paradigms recognized by students pursuing education to secure waged employment. This also affects how students perceive innovative courses and, consequently, how institutions promote education in a society facing systemic challenges. Should academia prepare students for existing jobs, or support them in creating innovative new ones?

The PAR methodology seeks to reorient hierarchical relations in the production of knowledge, disrupting conventional ways of doing teaching, research and practice. By positioning communities not as subjects but as co-researchers whose lived experiences are central to the inquiry, we can frame the third space of the commons as an environment that straddles between the academic institution and the city. The term ‘learning commons’ is here framed to describe this space.

4.1. Learning Commons

The current literature on ‘learning commons’ is in library and media studies, and the realm of digital repositories of information [

29,

30,

31]. Some literature exists on the quality of the physical spaces in libraries as important in shaping the learning commons as places where the educational community can collaborate, work together and mutually support each other [

30] (pp. 2–19). The author’s book entitled Commons and Public Partnership: Commons as Third Political Sphere has a chapter on ‘learning commons’ as being embedded in informal learning within local neighborhoods focusing on communities that occupy a space between households and the state [

15]. There, she defined ‘learning commons’ as environments that can build capacity and resilience by building a community of practice. The impact of ‘learning commons’ is heightened by being situated in a place through a civic classroom.

As the author describes, learning commons are community-based spaces designed to empower residents through civic education and dialogic learning [

32,

33,

34]. They have the potential to unearth residents’ knowledge and thus reduce status hierarchies by including both local and expert knowledge to develop solutions. Grounded in critical pedagogy and situated learning, they foster social mobility, political community building, and collaboration across diverse skills and identities. In essence, non-institutional learning commons are informal and locally governed. They value non-expert knowledge and aim to empower individuals and communities within a commons culture of sharing resources.

4.2. Institutional Boundaries

In the UK, higher education is controlled by two main institutional boundaries that restrict access: (1) a prior qualification to enter a master’s program, and (2) the finances required to provide students with access to the program. This paper does not address the issue of knowledge being monetized but instead focuses on how to enable access by reducing barriers based on prior qualifications. As a vocational-focused institution, London Metropolitan University permits students with prior experience in industry to enter a master’s program in art and design courses without a bachelor’s degree. Entry to Architecture is made more difficult due to professional qualifications. The removal of this barrier to access can improve social mobility for individuals who were unable to do a bachelor’s degree due to financial, social or cultural hindrances at a younger age. Entry to the program ‘Design for Cultural Commons’ was based on an interview, proof of prior community-engaged work and a statement of the applicant’s motivation to do the course. Situated students’ projects also enabled community members to engage with the program. They could also enter the program to gain academic credentials. Three students entered the course based on their participation in community-engaged projects of previous students. Students pay per 20 credit units. To make the program more accessible to a range of students, the author created PG. Certificate and PG. Diploma courses whose credits ranged between 60 and 120 credits rather than 180 credits required for a master’s qualification. This was to offer more affordable pathways into developing commons organizations (

Figure 8). The PAR methodology used in the design of the pedagogies outlined in this paper enabled learning commons to be conceptualized as spaces of knowledge transfer in localized neighborhoods.

4.3. Learning Environments

The PAR pedagogical methods lend themselves to expanding the formal learning environment outside the institution and creating learning communities in neighborhoods. This impacts participants’ everyday lives by exposing them to new ideas about commons systems and how they can engage in diverse political deliberation and self-govern local resources. These hybrid environments are found within grassroots organizations, urban spaces and local events, capturing undiscovered knowledge useful for systemic solutions. The intersection of educational and local spaces gives rise to new roles and forms of practice. The back-and-forth flow of knowledge, in neighborhoods and in institutions, offers mutual benefits in ways that an enclosure of knowledge cannot. In such a situation, the positions of student and master become blurred and thus have the potential to break the power relationship between educator and learner.

We explored two types of learning environments that, although we call them “classrooms”, operate as much looser learning environments. The first is The Civic Classroom, and the second is the institutional classroom. The Civic Classroom was a space for incidental encounters that valued the sharing of informal, localized and expert knowledge. The institutional classroom became a constant space of negotiation and tension between the institutional need for academic delivery and the space to process and evaluate the wider, unpredictable societal dynamics of students engaging with residents in live contexts. The permanent presence of both worlds expanded the institutional classroom’s learning environment, while presenting students with the challenge of deciding what to prioritize: the community or academic excellence.

4.4. Challenges of Community Action

What is the best way to establish collaborative relationships with community organizations, within the context of curriculum development? How can we cooperate to create learning commons and overcome knowledge enclosures imposed by neoliberal politics?

No partnership can exist without some level of hierarchy. The understanding of this power relation enables all involved to use a theory of relational power to design collaborative engagement. This allows power to flow, enabling everyone within the learning commons to have power during the partnership [

35]. This sharing of power, in which different forms of knowledge are valued, should not be seen as a loss of power by the expert but as the power of knowledge as a common asset within the community of learners to address complex problems. It is vital that the partnership clearly defines the expectations and needs of the communities involved at the most important stages of the action research process. This will help to ensure that the work is carried out ethically and that neither party uses the communities’ knowledge for their own private interests.

Empirical data from the program indicate that it takes at least one year to build relationships with communities, and that the institution must maintain those relationships after students graduate. After the first year, the clarity of the terms of engagement between students and residents is established to sustain collaborative relations between the university and the neighborhood. Complexities are involved when students engage in communities. In every London neighborhood we worked in, we found historical community conflicts from competition over resources and territories, to desire for power. Unraveling such historical conflicts requires the assistance of conflict resolution experts or years of engagement in a place. We understand that students should distance themselves from such conflicts, learn from them, and ensure their engagement does not create further conflicts or fuel existing ones. Setting boundaries based on realistic expectations for all involved is key. This is to protect students from being expected to do too much in the service of the community, which would result in them neglecting their studies, and to ensure that the community’s already scarce time is not used without reciprocity. Ensuring that students do not create conditions that could give rise to conflict between different parties in a neighborhood is the role of the teacher, who needs to be trained in conflict management. The teacher must also understand the capabilities and limits of the learning commons and be selective about which communities to collaborate with. Communities selected should be happy to engage and understand the reciprocal benefits.

The next step was to co-produce a neighborhood curriculum that included teachers, students, community members and practitioners as co-creators of the curriculum [

36]. Here, designing curricula becomes more about pedagogical agility than the linear design process that underpins brief making and module design. Achieving social and political impact is the driving force behind the ongoing work to co-produce teaching and learning structures. This, in turn, will redefine the role of curricula and the nature of final academic outputs. By questioning the canons within disciplinary fields, the learning commons provides a productive space in which to unlearn, and critique normalized pedagogical practices and values enclosed by disciplinary boundaries.

The curriculum that embraces plural values and methods of accessing knowledge beyond monetization is a key component of a learning commons. If all learners become members of the learning commons, a diverse range of skills and commitments will be represented in the learning environment, with both local and expert knowledge being valued. Actors within the learning commons become project collaborators in funded research, where finance can be circulated locally and support grassroots resilience.

5. Conclusions

The ‘Architecture and Activism’ design studio, rooted in PAR, demonstrated that architectural education can move beyond the conventional focus on form, function and esthetics to prioritize social engagement, activism, and commons-based practices. Through briefs such as ‘Letters to the Future Self’, ‘Cartography of an Object’, and ‘Campaigns of Disclosure’, students cultivated a deeper awareness of the political, ecological, and economic entanglements of architecture, situating themselves as both designers and agents of social change. However, the self-evaluation of this format highlights the enduring challenges of embedding PAR methods in accredited architectural education. Institutional assessment structures privilege outputs rooted in formalism and tasteful buildings over processes of activism, campaigning, and community mobilization. As a result, students navigating activist pedagogy often face additional burdens, working harder than peers whose outputs align more easily with traditional assessment metrics. This reveals a structural tension within architecture schools, where evaluative systems remain ill-equipped to measure the social, political, and ecological impacts of design interventions. However, the challenge in funding grassroots practices remains the prime concern.

The ‘Civic Classroom’ and ‘Civic Fragments’ further foregrounded architecture as a relational and community-embedded practice, emphasizing co-production of knowledge and civic agency. The transition from ‘Architecture and Activism’ syllabus to the ‘Design for Cultural Commons’ program reflects an attempt to overcome disciplinary limitations by fostering an interdisciplinary pedagogy situated in the broader discourse of the commons. By integrating modules across art, politics, sociology, law, and design, this curriculum reframed architecture’s activist potential within wider struggles for collective ownership, ethical labor, and community resilience.

Reimagining architectural education through PAR and commons-based approaches offers pathways for architects to act as civic agents, activists, and commoners, capable of intervening in political and ecological systems. At the same time, it underscores the need for institutional reform in assessment and accreditation, without which the transformative potential of such pedagogies will remain only partially realized.

To address the complex systemic problems of today, the paper conceptualizes the learning commons as a socio-political space that values both informal, local and experiential knowledge and academic expertise. By embedding education within neighborhoods through civic classrooms and partnerships with community organizations, the learning commons fosters dialogic learning, political capacity-building, and social resilience. These hybrid environments challenge entrenched power relations by redistributing knowledge production and creating opportunities for unlearning dominant paradigms. If sustained, they can generate new forms of socially and politically engaged practice, positioning the university not as an extractive institution but as a collaborative participant in co-cultivating resilient communities.