Abstract

Place attachment, or the emotional bond between people and physical settings, is a central concept in urban design and environmental psychology. Although biophilic and restorative environmental frameworks have stressed the value of natural environments, empirical research investigating nature and place attachment often reduces naturalness to simple greenness metrics, leaving the role of aesthetic and visual structural qualities underexplored. This study addresses this gap by drawing on empirical aesthetics and Christopher Alexander’s theory of living structures, which frames aesthetics as an underlying order that gives rise to the experience of visual coherence and beauty. We conducted a multi-method quantitative case study on ten campus open spaces, combining a student survey (n = 447), timed-interval behavioural observations, independent aesthetic ratings, and computational image analysis. The data analysis relied on correlation and regression, as well as data triangulation from multiple sources that encompassed both subjective and objective measurements. Regression and mediation models showed that perceived restorativeness was the strongest predictor of place attachment, complemented by sense of community, perceived wholeness, and naturalness. Indirect pathways revealed that passive interaction enhanced attachment through restorativeness, while active interaction did so through a sense of community. Image-based metrics, particularly fractal dimension and entropy, were closely aligned with perceptions of naturalness and restoration, while behavioural observations confirmed the distinct roles of social hubs, solitary natural retreats, and transitional spaces. The findings demonstrate that both naturalistic structure and social affordances are essential to attachment, and that living structure qualities offer a valuable framework for linking aesthetic order to restorative and emotional bonds. These insights provide both theoretical enrichment and practical guidance for designing restorative and life-enhancing public environments.

1. Introduction

Public open spaces are among the most vital components of the urban fabric. They offer shared environments where daily life, community engagement, and cultural practices unfold. The design characteristics of these public spaces influence not only patterns of use but also the psychological and emotional bonds that people form with their surroundings. Understanding the qualities of public open spaces that foster such meaningful connections is a central concern in contemporary urban design.

Central to these aims is the notion of place, which is conceived as more than abstract space, and forms a nexus of physical form, social interaction, and symbolic meaning [1,2]. Place attachment refers to the emotional ties that individuals and groups develop with physical settings. It is shaped by personal factors (e.g., age, gender, income, length of residence), social factors (e.g., interaction, community, culture), and physical factors (e.g., accessibility, greenery, built form) [3,4]. Classical place research has focused on the social dimension, with social interaction emerging as a major factor that leads to an enhanced sense of community and place attachment [4].

Recent place-based research has also looked at physical components, particularly emphasising the role of nature in enhancing place experience through its restorative potential [5,6,7,8]. Nature supports experiences of ‘being away’, replenishing exhausted psychological resources [9]. Repeated restorative experiences pave the way for more lasting attachments [10,11]. In urban contexts, the presence of green spaces is a common object of investigation. However, the role of nature extends beyond exposure to green space. It also involves the underlying formal and aesthetic structure of environments [12,13]. Research has shown that aesthetic qualities of place, often operationalised as the appreciation of visual beauty, landscape quality, and design character, contribute to place attachment [14,15,16,17]. However, aesthetics in place research is often treated broadly, reduced to measures of satisfaction or preference, leaving a gap in understanding the role of aesthetic structure in fostering attachment to public settings.

Recent advances in landscape aesthetics, empirical aesthetics, and neuroaesthetics are beginning to move beyond subjective preference models toward identifying the perceptual and structural features that shape aesthetic experience, which can be encompassed in such concepts as coherence, complexity, symmetry, and fractal scaling [18,19,20]. These developments provide methods for describing the physical environment in objective and operational terms, enabling researchers to transition from general discussions of preference to tangible links between place attachment and environmental aesthetic principles. Prefiguring this paradigm, Christopher Alexander’s theory of living structures introduced a coherent framework for connecting aesthetic order with human experience [21]. In The Nature of Order, Alexander proposed that both natural and designed environments are organised through a principle of wholeness, defined as the underlying and pervasive structural quality that arises from the interplay of a system’s parts and is responsible for experienced beauty and harmony. Alexander reframed aesthetics not as surface beauty or subjective preference, but as an objective structural condition that shapes the experience of place. Both restorative environments and empirical aesthetics perspectives converge due to a shared biological basis: aesthetic pleasure has been linked to visual patterns and proportions that embody the organisation of living systems, while restorative environments theory similarly locates psychological benefits in contact with nature and its characteristic forms of order.

This study examines the role of aesthetic–restorative qualities in the development of place attachment, alongside more established social interaction factors in the context of public open spaces on a college campus. Building on this theoretical background, the study tested the following hypotheses:

H1.

Place attachment is jointly predicted by aesthetic–restorative perceptions (e.g., perceived naturalness, perceived aesthetic order, and restorativeness) and social factors (e.g., interaction and sense of community).

H2.

Places that support higher levels of social interaction and social affordances yield stronger attachment outcomes.

H3.

Spaces exhibiting greater structural richness—quantified through image-based metrics such as fractal dimension and entropy—correspond to higher perceived aesthetic–restorative qualities.

Conceptually, this study aims to link aesthetics-oriented frameworks with theories of place. Empirically, it applies a multi-method approach, combining surveys, behavioural observations, and image-based analysis, to capture both subjective and objective dimensions of place experience. These contributions enrich urban design scholarship by grounding the concept of place in aesthetic and structural principles, while also offering practical insights into designing public spaces that support restoration and attachment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Theory of Place Attachment

Place attachment has been one of the most enduring and influential concepts in environmental psychology, humanistic geography and environmental design. It refers to the affective bonds that connect people to meaningful settings [1,2,3,22,23,24]. It is widely regarded as a relational process and an outcome of continuous interaction between individuals and their physical and social environments [4]. From this perspective, attachment develops as people interpret, value and act within particular places, integrating them into their cognitive self-image and emotional responses.

Scholars have conceptualised place attachment in multiple ways, ranging from phenomenological interpretations of dwelling and belonging [25] to attitude-based models that emphasise measurable components [26,27]. The latter approach, dominant in empirical research, treats place attachment as a multidimensional construct consisting of affective, cognitive and behavioural elements that together express a person’s evaluation of a meaningful setting. Although the field lacks a complete consensus on its dimensional structure, a large body of literature defines attachment through two key aspects: place identity and place dependence. Place identity reflects the emotional and symbolic ties that allow individuals to integrate a setting into their self-concept [28], while place dependence refers to the functional fit between the environment and the individual’s goals or activities [29]. The scale developed by Williams and Vaske [27] operationalised these two dimensions and remains the most widely used measure of place attachment. A more recent instrument [30] builds on these earlier measures by developing the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS), a concise and psychometrically validated measure that retains these two dimensions while reducing redundancy and respondent burden.

The development of place attachment can be understood by referring to the organising tripartite framework [3]. According to this model, place attachment develops through the interplay of person, place, and process dimensions. The person dimension concerns who is attached (the individual or collective characteristics that shape attachment tendencies). Place refers to the physical and social attributes of settings that serve as the object of attachment, with both tangible physical qualities (e.g., layout, coherence, landscape content) and social affordances (e.g., opportunities for interaction, community bonds). The process dimension captures the affective, cognitive, and behavioural mechanisms through which attachment develops and is maintained.

Under the place dimension, decades of empirical research have identified a wide range of social and physical predictors of attachment. The physical setting provides the aesthetic, functional, and restorative conditions that anchor perception and use, while the social fabric imbues places with community, belonging, and security [31,32,33,34]. When explaining their attachment, people may be more inclined to cite social, environmental, or a combination of both factors as reasons for attachment [31]. The relative weight of social versus physical factors remains contested and context-dependent. Due to these contested findings, some scholars view place attachment as primarily social, with physical form acting as backdrop; others argue that place is inherently a constantly evolving fusion of material setting and human process, making the two inseparable [35].

2.2. Social and Physical Predictors of Place Attachment

The social underpinnings of place attachment are well established. Historically, interest in the social dimension has outweighed attention to the physical, largely because early work stemmed from community studies where place was treated as a container of social relations [4]. Social factors, such as neighbourhood ties, trust, and community participation, have been consistently shown to predict stronger attachment [31,36]. In public settings, social interaction is a major correlate of place attachment [4]. Social interaction refers to the observable behaviours and encounters through which individuals relate to one another and to the environment. From a sociological perspective, interaction in public space ranges from brief visual contacts and incidental co-presence to sustained, face-to-face encounters [37,38,39]. Social interactions constitute the micro-foundations of public life, linking individual behaviour to the collective vitality of places. Classic urban design theorists [39,40] demonstrated that the physical layout of space can invite or inhibit interaction. Whyte’s idea of triangulation showed that small design features such as fountains, performers, or café edges can spark casual encounters, while Gehl distinguished between necessary, optional, and social activities, observing that the latter flourish in comfortable and human-scaled environments. Building on these foundations, Mehta [41,42] operationalised two forms of social interaction: active (direct engagement such as conversation or shared activity) and passive (co-presence or observation). His studies revealed that even low-intensity encounters contribute to feelings of safety and belonging, and that spaces facilitating passive interaction often evolve into settings of active engagement.

While social interaction reflects observable behavioural patterns, a deeper form of social connection to place develops through a sense of community. This refers to feelings of belonging, mutual influence, and shared emotional connection, grounded in four dimensions: membership, influence, fulfilment of needs, and shared emotional bonds [43]. The meaning of “community” may vary depending on whether it refers to geographically bounded settings or interest-based groups [44]. Across environmental psychology and community studies, sense of community has been closely intertwined with place attachment, with empirical studies showing that social belonging, mutual influence, and local identity strengthen emotional bonds to places [45,46,47,48].

The physical environment has also been extensively examined as a predictor of place attachment, though its formulation is less agreed upon. The selection of variables has often been arbitrary and lacking a theoretical basis [4]. Commonly studied features include greenery and natural elements, walkability and accessibility features, maintenance, spatial scale, and architectural character [49,50,51,52]. The role of the physical setting has been more systematically theorised in urban design theory, from Lynch’s triads of form-activity-meaning [53] to the definition of place-making as the integration of setting, activity, and meaning [54,55]. Yet across these theories, the aesthetic and structural principles underlying why certain environments feel coherent, organic, or restorative remain underexplored. When aesthetics is considered, it is often treated broadly; operationalised as attractive architecture, traditional styles, visual harmony, or perceived complexity and harmony [50,56,57]. These critiques converge on a shared gap: despite disciplinary differences, there is a lack of frameworks that systematically explain how the formal and aesthetic order of environments contributes to place attachment. This also calls for a reconsideration of the physical vs. social influence debate in light of environmental aesthetics frameworks.

2.3. Aesthetic–Restorative Quality of the Environment

An overwhelming amount of evidence supports that exposure to naturalistic environments promotes psychological benefit and well-being [58]. Much of this evidence stems from the restorative environments theory, which explains how specific environments facilitate individuals’ recovery from stress and mental fatigue [9,59]. Four components characterise restorative settings: compatibility (supporting individual needs and goals); being away (escape from routine demands); fascination (effortless, non-demanding attention); and extent (a coherent, immersive structure that invites exploration) [9]. Decades of empirical research have substantiated the theory across multiple contexts, confirming that environments perceived as restorative are associated with improved mood, attentional recovery and well-being [59]. Additionally, restorative experience often mediates the relationship between environmental perception and place attachment: places perceived as restorative are more likely to foster emotional bonds, and attachment can, in turn, deepen restorative benefits [5,11,60,61]. In this sense, restoration functions not only as a short-term psychological benefit but also as an affective mechanism linking environmental qualities to place attachment.

While restorative environment theory emphasises the process of restoration, it says less about the form of environments that evoke it. Nevertheless, numerous studies have found that certain aesthetic and visual-perceptual qualities strongly predict perceived restorativeness, with most showing that natural environments are consistently rated as more restorative than urban ones [62,63,64,65,66]. Early restorative environments studies focused primarily on content, such as the presence of greenery or water, whereas recent work emphasises the role of form, including concepts like coherence, complexity, textural richness, symmetry, and visual balance, in shaping how environments are perceived and felt beyond simple aesthetic preference [66,67]. This insight is mirrored by contemporary design approaches that call for greening urban environments not merely by adding explicit natural content (nature in space), but by embodying the formal and structural order (nature of space) that makes natural settings aesthetically pleasing and restorative [12,13]. The term aesthetic–restorative quality is used in this study to denote this integrated experiential domain, where the experience of restoration arises through aesthetic experience.

Landscape aesthetics frameworks help discern these qualities and their potential role in restorative experience. Classical theories such as Gestalt psychology and prospect–refuge theory were centred around perceptual ease or environmental content. Recent developments in neuroaesthetics and empirical aesthetics have renewed interest in how specific formal and structural properties of environments influence aesthetic experience and emotional response. Computational modelling and machine learning have made it possible to test features that predict aesthetic judgments and understand underlying brain mechanisms [68]. Christopher Alexander’s theory of living structures represents an early synthesis of principles now being validated under this new paradigm of objective aesthetics. It posits that aesthetic experience is rooted in the structural order of environments themselves, an order that arises from the way spatial elements interrelate across different scales, governed by geometrical laws that mirror laws of physics and biological growth [21]. His model subsumes content and perception into a principled structural ontology. For studies of place, it is especially apt: it allows the environment to be treated as an active, living entity whose internal coherence, scale relations, and structural complexity shape attachment, mainly through aesthetic–restorative quality, rather than simply being a passive backdrop or stimulus.

In The Nature of Order, Alexander describes wholeness as the underlying order that makes certain environments, artefacts, and buildings feel more alive, coherent, and beautiful [21]. It arises from a field of centres (or a system’s parts) that mutually reinforce one another across scales, from small architectural details to urban layouts. Wholeness refers both to a visible structural pattern and to a felt quality of “life” in space. Alexander emphasised that when wholeness is present, people experience environments as “whole, comfortable, and free of inner contradiction” and describe them as “alive, beautiful, and harmonious” [21]. In earlier work, he called this the “quality without a name,” noting that great places often seem “timeless” and imbued with a sense of welcoming comfort [69]. These experiential dimensions: beauty, unity, warmth and comfort, life, and timelessness, capture some of the aspects of the lived experience of wholeness. They provide a conceptual basis for examining how structural properties translate into emotional responses in everyday settings.

A major contribution of this framework is the identification of 15 fundamental properties of living structure. These represent spatial and geometric arrangements that strengthen centres and maximise structural coherence. They include principles such as levels of scale, strong centres, boundaries, gradients, contrast, and local symmetries. The properties occur in both natural systems (e.g., tree branching, coastlines) and the built environments (e.g., historic squares, building facades). Alexander emphasised that the more these properties overlap, the stronger the sense of life and coherence. Importantly, they are not prescriptive design rules, but rather outcomes of a generative process, whereby environments evolve step by step through “structure-preserving transformations” rather than top-down imposition—a process that can be observed in organic forms and natural processes. This perspective is valuable both for design practice and for interpreting existing places shaped by incremental change.

Empirical research, though still limited, supports some of these ideas. A recent study found that judgments of naturalness and beauty in buildings correlate with features such as fractal complexity, contrast, and edge density, which serve as proxies for two fundamental properties [70]. Jiang [71,72] proposed computational measures of living structure, simplifying the 15 properties into two scaling laws: (1) far more smalls than larges, and (2) repeating substructures across scales. Using the head/tail breaks mathematical scheme, he proposed a possible measurement of structural beauty [71,72]. Beyond the validation of these ideas, empirical aesthetics research combining computational metrics and neuroscience continuously shows that fractal geometry, moderate complexity, and curvature—features abundant in natural settings—predict both visual preferences and measurable neural responses (and even reduced stress) in real environments [18,73,74,75,76]. However, claims of objective aesthetics remain a subject of debate. Some critics have challenged the universality of ‘beauty’ or ‘life’, arguing that what feels ‘alive’ or coherent may depend on cultural familiarity, symbolic associations or situated meanings rather than purely geometric properties [77,78,79]. This critique is particularly relevant to place research, where complex interrelated physical and social facets shape attachment. Wholeness and structural beauty risk circularity if detached from measurable perceptual processes. Contemporary neuroaesthetics and embodied cognition suggest that aesthetic pleasure results from the interaction between perceiver and environment, through neural efficiency, sensorimotor resonance, and affective engagement, rather than solely from formal order [68,80].

While these critiques highlight the limits of universal or purely formal accounts of beauty, they also underline the need for an integrative approach that links structural order with the lived, psychological experience of the built environment. In this study, the notion of aesthetic–restorative quality is understood as the convergence of perceptual coherence, naturalistic structure, and restorative experience, examined in relation to place attachment. Within this framework, the concept of living structure provides a vocabulary for translating the geometry of space into experiential constructs. In doing so, the study employs living structure as an interpretive and operational model that bridges objective spatial form with the emotional and restorative dimensions of place.

2.4. University Campuses as Sites of Place Experience

Across the world, universities compete to create green, attractive campuses as part of institutional branding and to enhance student experience [81,82]. This trend is reinforced by global sustainability rankings such as UI GreenMetric and AASHE’s STARS framework, which assess not only academic excellence but also ecological design and campus liveability [83,84]. Campuses often act as testing grounds and pioneering exemplars for landscape and urban design ideas, and their compact, mixed-use settings make them ideal for studying how design supports well-being, social life, and place attachment.

Empirical research confirms the importance of environmental quality in enhancing the campus experience and promoting student well-being. One Study found that students who perceived their campus as greener reported a higher quality of life, mediated by perceived restorativeness [85]. In a cross-cultural study across U.S. and Turkish campuses, researchers confirmed that both objective greenness and perceived greenness were linked to restoration and improved quality of life [86]. More recent studies highlight specific mechanisms: sensory richness and solitude opportunities [87], greenery and biodiversity [88], and sensory dimensions such as “serenity” or “refuge” [89]. The evidence shows that naturalistic features, such as greenery, sky views, biodiversity, and sensory richness, predict students’ restoration, well-being, and sense of belonging.

2.5. Summary

The reviewed literature demonstrated that place attachment is a multi-dimensional construct influenced by various social and physical factors. While both are well-documented, the aesthetic and structural attributes of spaces remain underexplored. Research in biophilia and restoration highlights the psychological benefits of nature, while Alexander’s theory of living structures provides a systematic account of aesthetic order. Together, these perspectives suggest that both the content and the form of environments contribute to restorative experiences that may strengthen place attachment.

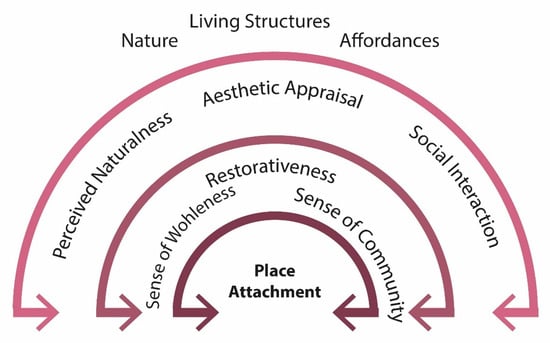

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework guiding this study. It depicts a layered model in which the objective environment is perceived and interpreted through experiential mediators, which in turn support the core bond of place attachment. Restorativeness and sense of community are conceptualised as experiential mediators that reflect the physical and social dimensions of place experience. Restorativeness represents the psychological mechanism through which natural and aesthetically coherent settings support recovery, comfort, and reflection, capturing the individual’s affective response to the physical environment. Sense of community reflects the social mechanism through which shared use, participation, and interpersonal relationships within a public space setting foster belonging and collective identity. Together, these constructs describe how environmental qualities are internalised through both restorative and social experiences, providing complementary pathways that translate spatial form and activity into emotional attachment.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of the study.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted an exploratory multi-method case study design, focusing on a college campus setting with multiple outdoor spaces analysed as embedded, comparison-based units. The case study approach is particularly suited to the aims of this research, as it integrates multiple sources of evidence, supports theoretical development, and situates findings within real-life environments [90]. This enables an in-depth examination of how physical design, social interaction, and individual perception intersect to shape the place experience.

The study was conducted at the Istanbul Technical University (ITU) Ayazağa campus located in Maslak District, in Istanbul, Turkey. The campus combines contemporary built facilities with green and extensive outdoor areas. The naturalistic qualities of its open spaces make it a suitable setting to test the influence of restorative environments, while its diversity of design styles provides variation for comparison.

Within the campus, ten distinct open spaces were identified as embedded units of analysis. The selection of campus open spaces followed a systematic process combining field observation, user input, and design-based criteria. The aim was to identify spaces that were both relevant to student life and diverse in their environmental characteristics, ensuring meaningful comparison across physical and experiential qualities.

The process began with extensive site visits and photographic documentation of the campus to record the spatial, visual, and ecological features of potential study areas. Informal conversations with students complemented this phase: participants were asked to name their most frequented outdoor places on campus. This initial phase yielded a list of twenty candidate sites, including plazas, lawns, courtyards, and recreational areas. From this list, ten open spaces were selected based on the following criteria:

- Proximity and relevance: priority was given to spaces that are well-integrated into the pedestrian circulation system and adjacent to major academic and social facilities, such as major faculties, lecture halls, libraries, and student centres. Peripheral or semi-private areas were excluded.

- Accessibility: Only spaces fully open to all campus users, regardless of faculty affiliation, were included.

- Spatial definition: Each site had to possess a clear spatial enclosure, defined by architectural, natural, or infrastructural boundaries, to allow consistent observation and visual assessment.

- Environmental variety: The final selection represented a gradient from vegetated, naturalistic areas to built, hardscaped environments, enabling comparison across levels of perceived naturalness and aesthetic order.

- Observational and evaluative feasibility: Sites were required to be of manageable size and coherent spatial character to facilitate systematic behavioural observation and perceptual evaluation.

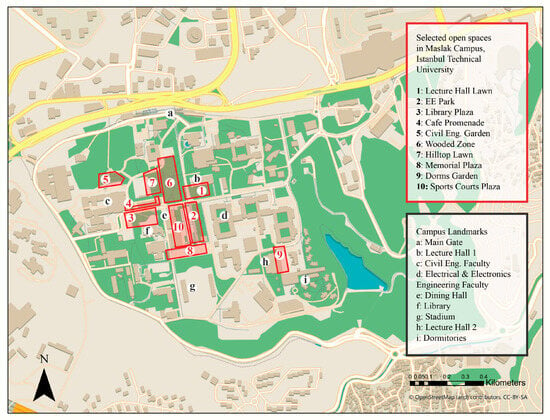

Figure 2 illustrates the locations of the ten selected sites, and Table 1 presents photographs of the settings along with a brief description of each.

Figure 2.

Location of the ten selected open spaces within the ITU Ayazağa campus. Base map data © OpenStreetMap contributors (ODbL 1.0), rendered by Carto (Voyager No Labels). Map prepared by the author.

Table 1.

Description of the selected sample of open spaces on Ayazağa campus.

The study was designed as a multi-method study with an objective to triangulate subjective and objective sources of data to enhance internal validity and capture different dimensions of place experience. Four complementary components structured the design:

- 1.

- Survey of users (students): An online survey built on the SurveyMonkey platform was distributed to a representative sample of the university’s student body. The university’s student population was approximately 40,000. Based on a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and an assumed population proportion of 0.5, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 381. The achieved sample of 447 corresponds to an achieved precision of approximately ±4.6%, indicating adequate statistical power. Demographic checks showed balanced representation across gender, study level, and faculties (Table 2). The survey link was distributed through the university’s official mailing lists and student networks to reach all faculties and study levels, while the introduction specified that responses were sought only from students who regularly use the Ayazağa campus, as some faculties are located on remote campuses. Participation was voluntary, but open access to the entire student body allowed responses to approximate a probability-based sample. Demographic checks confirmed balanced representation across gender, faculty, and study level, supporting the representativeness of the final sample (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the student sample (n = 447).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the student sample (n = 447).

The survey measured psychological constructs derived from the conceptual aims and framework (see Appendix A). These include Place Attachment, measured using the six-item abbreviated scale, including place dependence and place identity [30], Perceived Restorativeness; measured with a 4-item scale based on the four dimensions of restorative experience [91], and seven measures developed by the authors; namely Passive/Active Social Interactions (3 item each) Sense of Community (3 item), Perceived Naturalness (5 item), and two novel measures were also derived from Alexander’s theory of living structure; Sense of Wholeness (5 item) and Perceived Order (6 items), the former interpreting some of the experiential aspects of spaces rich in living structures, and the latter measuring perception of 6 of the 15 properties, translated into semantic differential scale. Other variables included frequency and familiarity with the setting. All main variable items were measured on a scale of 1–5, including agreement-type Likert scales and semantic differential items. In addition, the survey included open-ended questions about place meaning associations and activities, as well as questions that collected demographic and personal information. The survey was offered in both English and Turkish, and pilot-tested to assess clarity, wording, and content validity prior to its full distribution. To reduce fatigue, questions for the ten settings were rotated among participants in three blocks.

- 2.

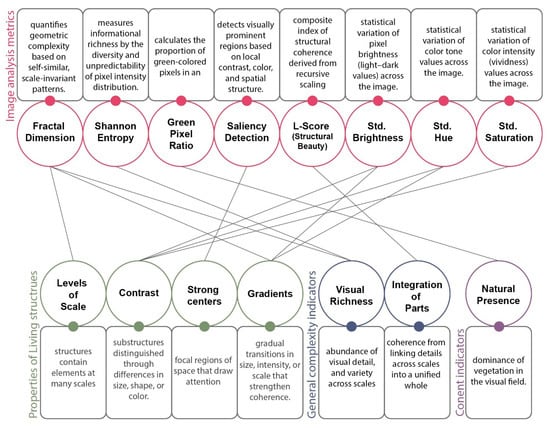

- Image-based computational analysis: We employed image analysis techniques to draw on objective measures of aesthetics that approximate some of the general qualities and properties of living structures by building on previous work in computational aesthetics. For example, Ref. [70] found that fractal dimension, entropy and other metrics correlated with judgments of naturalness and beauty in architecture, reflecting two of the 15 fundamental properties: levels of scale and contrast. Similarly, Refs. [71,72] formalized structural beauty (L-score) through recursive scaling laws, demonstrating that elements of Alexander’s framework can be quantified mathematically.

Building on previous work, the present study employed a set of metrics as proxies for structural properties, expanding the range of indicators. In addition to measures used in prior studies (fractal dimension, Shannon entropy, variation in hue, saturation, and brightness), green pixel ratio was used to capture the immediate nature in space, saliency detection, to approximate strong centres and contrast through visually prominent regions; and the L-score, a composite index of structural beauty based on recursive order. Together, these measures approximate both specific properties (e.g., levels of scale, strong centres, boundaries) and broader qualities of living structures such as multiscale complexity, informational richness, and ecological integration. Figure 3 outlines the image analysis metrics and their link to properties of living structures. These links represent proxies rather than one-to-one translations, providing a structured but approximate means of operationalising Alexander’s concepts for empirical analysis.

Figure 3.

Computational measures (pink) approximating aspects of living structures. Some metrics align with specific properties (green), while others correspond more broadly to qualities of wholeness (blue) or content indicators (purple).

In practice, standardised photographs of the ten campus open spaces taken by the author were analysed using open-source Python scripts (version 3.8.10), and mean scores for each metric were calculated across images to represent the structural profile of each setting. This procedure enabled empirical testing of whether environments richer in structural coherence and complexity also elicited higher perceptions of aesthetic–restorative perceptions.

- 3.

- Behavioural observations: A structured behavioural observation protocol was employed to document patterns of user activity and social interaction modes within the selected campus open spaces. This component complemented the survey and image analysis by providing objective behavioural evidence of how different environments support social use. A standardised observation sheet was developed containing a list of predefined behavioural categories with quantitative entries reflecting the observed number of people. Pilot trials were conducted to calibrate category coding. These final checklist recorded people who were observed alone, in groups, engaged in active interaction (such as conversation, shared activity, exercise), passive interaction (co-presence without engagement, looking at phone, reading, people-watching) and predetermined categories of behaviour types (eating/drinking, meeting/talking, playing/exercising, using phone, passing by, other). A mark was noted in each box corresponding to the category for each observed person; the total number of people present at the site was later calculated and entered. A timed interval scan method was applied, in which all visible behaviours were recorded as a snapshot at five-minute intervals over 30 min sessions (six scans per session). Each location was observed during three daily periods: morning (09:00–12:00), midday (12:00–14:00), and afternoon (14:00–17:00) on regular weekdays in April and May 2025, excluding days with atypical weather or events. When activity levels were moderate, data were recorded directly on paper; in busier periods, observations were narrated into a voice recorder phone app and later transcribed. A single observer conducted all sessions, and at each site, the observer positioned themselves at a fixed vantage point that offered the widest possible view of the area while remaining unobtrusive to users. In spaces with limited visibility or physical obstructions, short walkthroughs were conducted at each time interval to ensure full coverage. In one high-density location, the Lecture Hall Lawn, individual counting was not feasible during peak hours; therefore, numbers were estimated based on group averages and zone density to maintain consistency across sessions.

- 4.

- Independent aesthetic ratings: To compare user vs. non-user evaluation of the visual aesthetics dimension, an independent group of non-user participants took a visual aesthetics survey. The independent rater group (n = 150) was recruited through the Prolific online research platform. Eligibility criteria included age between 18 and 65 years, a minimum high school education, and current residence in the United States or the United Kingdom to ensure both English proficiency and cultural distance from the study setting. These raters, unfamiliar with the campus, assessed images of the same spaces using the semantic scales from the student survey, which measured Sense of Wholeness and Perceived Order properties. This comparison enabled the study to test bias, which can be generated from contextual familiarity and attachment, and to uncover whether there are generalizable aesthetic tendencies.

Data were analysed at the level of places rather than individuals, allowing both within-site and cross-site comparisons. The triangulated design facilitated cross-validation of findings: survey data captured subjective impressions, observations provided behavioural evidence, image analysis quantified physical properties, and independent ratings tested broader aesthetic principles and the effect of bias. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.2, while Microsoft Excel was employed for organising data and generating graphs and summary visualisations. Ethical approval was obtained from the Istanbul Technical University Ethics Committee, and institutional permission was secured for survey distribution. Participation was voluntary, with confidentiality ensured.

4. Findings

Data analysis proceeded in two stages: (1) identifying correlations and predictors of place attachment across all campus sites, and (2) comparing across the ten sites using the survey, image analysis, independent ratings, and observations.

4.1. Predictors of Place Attachment

Reliability analysis indicated acceptable to high internal consistency for all measured constructs with Cronbach’s α values exceeding the 0.70 threshold (see Table 3)

Table 3.

Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) for the study constructs.

Reliability, correlation, and regression analyses employed two-tailed tests (α = 0.05). Pearson’s correlation analysis across the ten campus settings showed that Place Attachment was strongly correlated with Perceived Restorativeness (r = 0.72), Sense of Wholeness (r = 0.63), and Perceived Naturalness (r = 0.60). As expected, Sense of Wholeness and Perceived Order strongly correlated, confirming the shared theoretical relevance (r = 0.75). Moderate correlations were also observed between Place Attachment and social constructs, particularly Passive Social Interaction (r = 0.57) and Sense of Community (r = 0.49). Contrary to expectation, Frequency of visits was negatively correlated with place attachment (r = −0.38), suggesting that bonds were generally more strongly generated in places outside of routine daily use.

To identify the key predictors of Place Attachment, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted across all settings, using seven independent variables (see Appendix B). The model explained 57.8% of the variance in Place Attachment. Four variables had significant contributions:

- Perceived Restorativeness (β = 0.43, p < 0.001): the strongest predictor, uniquely explaining 5.3% of the variance in Place Attachment.

- Sense of Community (β = 0.26, p < 0.001): explained 2.28% in unique variance.

- Sense of Wholeness (β = 0.16, p = 0.006): contributing only 0.66% of unique variance.

- Perceived Naturalness (β = 0.10, p = 0.032): explaining 0.40% of variance.

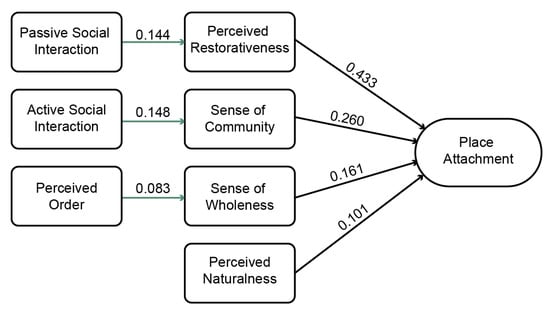

Because this initial model showed that Active Social Interaction, Passive Social Interaction and Perceived Order did not have significant direct effects on place attachment, mediation analysis was employed to explore indirect effects through the strongest experiential predictors, restorativeness and sense of community. This empirically guided step reflects the theoretical expectation that attachment develops through both restorative and social experience and that the properties of order are theoretically linked to Sense of Wholeness. Mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 5000 bootstrapped resamples. First, Passive Social Interaction contributed to Place Attachment indirectly through enhanced perceptions of Restorativeness. (Effect = 0.14, 95% CI [0.10, 0.19]). The relationship between Active Social Interaction and Place Attachment was completely mediated by Sense of Community (Effect = 0.15, 95% CI [0.09, 0.21]). This suggests that the social interaction dimension of campus spaces operates through restorativeness and community ties rather than individual acts of interaction. Finally, Perceived Order also had a significant indirect effect on Place Attachment through Sense of Wholeness (Effect = 0.08, 95% CI [0.02, 0.15]), which confirms a hypothesised path from perceived visual and structural aesthetics properties to psychological outcomes. Figure 4 summarises the results from regression and mediation analysis.

Figure 4.

Results of regression and mediation analyses showing predictors of Place Attachment. Arrows indicate significant paths with standardised coefficients (β).

4.2. Comparative Pathways to Attachment

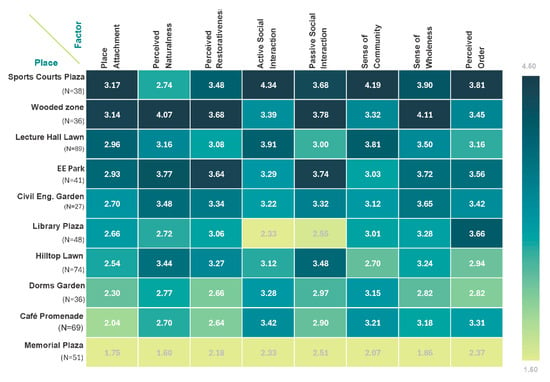

At the place level, mean scores were calculated for each measured construct in the survey. Combined with one-way ANOVA, these provided a comparative understanding of how perceptual variables differed across the sampled locations (see Appendix C). First, Place Attachment varied across the ten sites: Four settings achieved relatively higher levels of Place Attachment (3.00–3.20), three fell in the mid-range (2.50–3.00), and three scored lowest (1.75–2.30). A Welch ANOVA followed by Games–Howell post hoc confirmed statistically significant differences in Attachment scores (F(9, 167.17) = 13.29, p < 0.001). The effect size was large (η2 = 0.19, ω2 = 0.17), indicating that between-place differences accounted for approximately 17–18% of the variance in Place Attachment. High-attachment places (e.g., Sports Courts Plaza, Wooded zone, Lecture Hall Lawn) scored significantly higher than low-attachment places (e.g., Memorial Plaza, Cafes Promenade). Specifically, Memorial Plaza scored significantly lower than most other locations, while Sports Courts Plaza scored significantly higher than several others. Figure 5 illustrates a means comparison matrix of factor scores for each setting. Comparing these scores, some places appeared as all-rounders, performing consistently across most measured variables, whereas others leaned more toward either social or naturalness/aesthetic dimensions.

Figure 5.

Mean comparison matrix of survey measures across the ten campus open spaces. Values represent mean scores on a 5-point Likert scale, normalised within each column. Places are ranked according to their mean place attachment score (first column). Darker cells indicate higher relative values within each variable.

To illuminate these emerging patterns of place experience, the meaning association multiple-choice question and open-ended questions in the survey were analysed qualitatively, and the results so far were combined with other data sources. Place meaning questions included, “What comes to mind when you think of this place?”, “What do you typically do when you are here?” and “If there was anything you could change about this place, what would it be?”. Table 4 presents the extracted themes for each setting, along with illustrative evidence, triangulated with quantitative scores of key aesthetic–restorative and attachment perception scores.

Table 4.

Qualitative Themes of place associations for the ten settings.

By comparing survey and observational results, the following themes were found to underlie place experience in the selected settings:

- Natural retreats: places which had dense vegetation, a secluded enclosure with greenery, or picturesque nature, such as the Wooded zone, the EE Park, the Hilltop Lawn and the Civil Eng. Gardens were appreciated for the sense of peace and quiet they afforded, while scoring moderate to high on naturalness and attachment. The observed interaction in these spaces was dominated by passive as well as mixed use. While most settings averaged moderately in terms of the number of people present per observation period, the Hilltop Lawn had the sparsest visitation, which may have increased its value for some students as a “getaway” place.

- Social Hubs: these are places that were recognised for their role in affording social contacts, food, and other community interactions. The Lecture Hall lawn had the highest social presence with dominant active interactions in groups. However, it was also the place that generated some negative feedback regarding overcrowding and a lack of hygiene. While reported as a social contact and food attraction, the Sports Courts Plaza had relatively lower observed social presence but was dominated by active and group interactions. Both these settings scored lower on aesthetic and naturalness ratings but high on Sense of Community. The Café Promenade had a balanced mix of social interactions and was primarily perceived through its eating activities; however, many students reported using this space only for passing through.

- Transitory places: some places were part of daily commutes rather than a destination for recreation activity, such as the Wooded Zone and Library Plaza. Observed and reported type of activity confirmed that these were spaces mainly used for passing by. However, despite the similar social affordance profile, the Wooded Zone still emerged as a restorative and highly attached setting, suggesting that even brief exposure to natural environments can foster meaningful bonds and support an ecological campus identity.

- Symbolic places: both the Library Plaza and the Monumental Plaza had symbolic meanings but resulted in different emotional responses. The Monumental Plaza was designed with an emphasis on university identity; however, the design was perceived in a dominantly negative way, with some participants commenting on its harshness and underutilization. Confirming this, a relatively small number of people were observed using this space and those who did were sitting passively on the edges facing the outside view. The Library Plaza was closely tied to the library building itself, evoking symbolic associations with academia, knowledge, and personal memories of studies, though many noted the lack of features that allowed lingering.

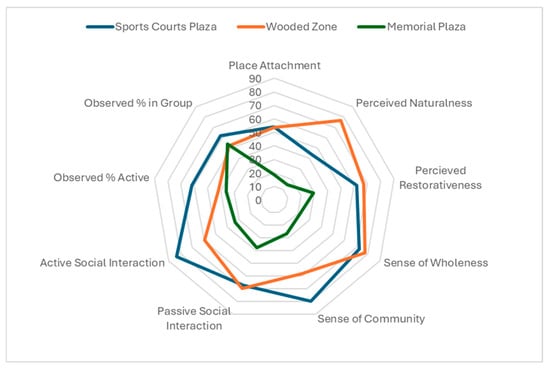

Figure 6 illustrates three different cases that show distinct profiles of natural retreats and social hubs, as well as the profile of the lowest performing place.

Figure 6.

Profiles of three campus spaces across social, restorative, and attachment dimensions. Survey-based indicators (place attachment, naturalness, restorativeness, wholeness, sense of community, active and passive social interaction) are shown alongside behavioural observations (% active use, % in groups), all rescaled to a 0–100% scale for comparability.

4.3. Convergence and Divergence of Computational Aesthetics Metrics and Human Judgments

Image analysis was conducted to examine whether measurable visual properties of the selected places aligned with users’ perceptions. Each place was represented by eight standardised images, analysed using Python scripts, and the mean scores of each metric were calculated. Correlations among the image-analysis variables revealed a strong structural cluster, with Fractal Dimension, Entropy, L-score, saliency, and Green Pixel Ratio all being highly interrelated (r = 0.40–0.81, p < 0.001), indicating a shared dimension of structural richness and naturalness. In contrast, colour-based measures showed weaker or independent relationships: Saturation was moderately related to Saliency and Entropy, while Hue variability was largely orthogonal, and negatively associated with Green Pixel Ratio.

Spearman’s rho correlations between objective indicators and survey constructs showed clear links between visual structure and perceived experience. Perceived Naturalness was most strongly associated, correlating with Fractal Dimension (r = 0.88, p < 0.001), Green Pixel Ratio (r = 0.84, p = 0.01), L-score (r = 0.74, p = 0.02), and Entropy (r = 0.702, p = 0.024). Perceived Restorativeness was similarly related to Fractal Dimension (r = 0.76, p < 0.001), Green Pixel ratio (r = 0.61, p = 0.004), and Entropy (r = 0.49, p = 0.02). Sense of Wholeness correlated with Fractal Dimension (r = 0.79, p = 0.007), while Passive Social Interaction was associated with Fractal Dimension (r = 0.86, p = 0.002) and Green Pixel ratio (r = 0.69, p = 0.03). Active interaction, Sense of Community, and Perceived Order showed weak or non-significant associations. Overall, Fractal Dimension emerged as the most consistent objective predictor, aligning with perceptions of naturalness, restorativeness, wholeness, and passive social engagement.

A principal components analysis of the image metrics extracted three dominant dimensions:

- Structural Complexity and Naturalness (Fractal Dimension, Greenness, L-score, Entropy, and Saliency).

- Colour–brightness contrast (Std Brightness, Std Saturation and Saliency).

- Diversity of tones (Std Hue).

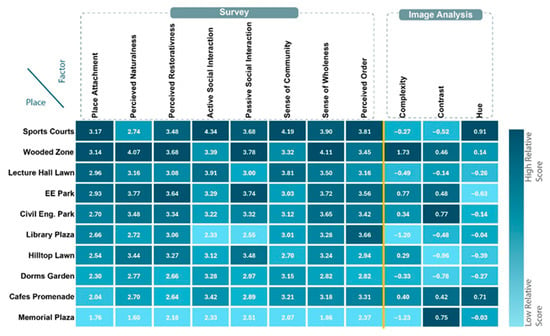

Comparing mean standardised scores across places revealed clear cross-site patterns. Figure 7 presents survey constructs alongside PCA-derived image factors, ranked by Place Attachment. The Wooded zone consistently scored high in both domains, suggesting that structural complexity and greenness strongly align with students’ place attachment. By contrast, the Sports Courts Plaza ranked highest in attachment and social interaction but did not stand out in image-based metrics, indicating that social use compensated for weaker visual complexity. Conversely, Library and Memorial Plazas scored lowest across both domains, reflecting their lack of supportive physical and experiential qualities. Overall, the findings suggest that while physical complexity and naturalness play a role in supporting psychological outcomes in some places, social and cultural meanings may play a decisive role in others. This further illustrates the previously illustrated place profiles of natural retreats and social hubs.

Figure 7.

Mean comparison of survey constructs and Image analysis compound factors, rows are ranked according to place attachment scores. Survey constructs are on a 1–5 Likert scale; PCA factors are standardised (z-scores, mean = 0). Darker cells indicate higher relative values within each variable.

In addition to image analysis, an independent group of 150 non-user participants evaluated images of the ten campus open spaces, along with five control images, on measures of Perceived Naturalness, Sense of Wholeness, and Structural Coherence. Each place image was rated 50 times. Unlike students, these raters had no direct experience of the settings and thus judged them solely on their visual qualities.

A one-way ANOVA with Games–Howell post hoc tests confirmed significant differences across places on all three constructs. As expected, naturalistic settings achieved the highest ratings: the Wooded zone scored strongest overall (Naturalness = 4.38, Wholeness = 4.08, Coherence = 4.04), followed by EE Park and Hilltop Lawn. In contrast, more formalised or built spaces, such as Dorms Garden, Memorial Plaza, and Library Plaza, consistently received the lowest evaluations (e.g., Dorms Garden: Naturalness = 2.48, Wholeness = 1.71, Coherence = 2.26). The control images aligned with expectations, with the naturalistic exemplar clustering alongside the highest-rated campus spaces.

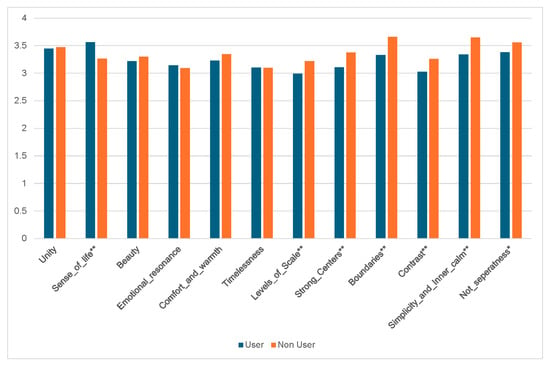

Independent-samples t-tests for individual survey items further revealed differences between students and non-users on individual items of the aesthetics judgment scales. Students gave significantly higher ratings on Sense of Life, t(996) = 3.58, p < 0.001, d = 0.22. By contrast, non-users rated several structural properties more highly, including Levels of Scale (p = 0.006, d = −0.17), Strong Centres (p = 0.001, d = −0.20), Boundaries (p < 0.001, d = −0.26), Contrast (p = 0.002, d = −0.18), Simplicity and Inner Calm (p < 0.001, d = −0.30), and Not-separateness (p = 0.031, d = −0.14). No significant differences were observed for Unity, Beauty, Emotional Resonance, Comfort and Warmth, or Timelessness (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

T-test comparison between users’ and non-users’ aesthetics ratings. (* weak significant differences, ** Moderate significant differences).

These findings suggest that while students connect more strongly to the vitality of places, non-users are more critical of structural and aesthetic dimensions, albeit with small to moderate effect sizes.

The evaluations provided by independent raters showed strong convergence with the results of the objective image analysis. Places such as the Wooded zone and EE Park, which were visually rated as highly natural and coherent, also scored highest in structural metrics, including Fractal Dimension, Green Pixel Ratio, Entropy, Saliency, and Std Saturation. Conversely, low-rated places, such as the Memorial Plaza and Library Plaza, also exhibited weak or negative z-scores in terms of Greenness, Entropy, and Saturation. This alignment reinforces the argument that independent raters, unconstrained by personal experience, respond primarily to the same visual-structural cues captured in objective measures.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the qualities fostering place attachment in open spaces arise from the interplay between their structural, aesthetic, and social characteristics. Restorative experience and sense of community together emerged as the strongest predictors, explaining the largest share of variance in place attachment. Across surveys, image analysis, independent ratings, and observations, two consistent pathways to attachment emerged: restorative bonds nurtured in nature-rich settings, and communal bonds forged in socially vibrant hubs.

A central contribution of this research is to demonstrate that the qualities described in Alexander’s theory of living structures closely align with perceptions of naturalness, wholeness, and restorative potential. Image metrics such as fractal dimension, entropy, green ratio, and structural beauty correlated with student perceptions of naturalness and restorativeness and converged with the evaluations of independent raters. These results suggest that environments rich in layered structural detail and coherent spatial order are not only aesthetically preferred, as prior neuroscience and environmental psychology have shown [70,92], but also play a role in forming deeper experiences of attachment. In Alexander’s terms, spaces that embody wholeness, coherent interplay of boundaries, gradients, and nested scales, are experienced as more “alive” and supportive of well-being.

The mediated role of wholeness is particularly revealing. Structural properties did not directly predict attachment but exerted influence through perceived wholeness, underscoring that no single attribute guarantees a positive experience. Instead, it is the integration of multiple properties into a coherent whole that elicits vitality and attachment. This finding empirically supports Alexander’s claim that aesthetic structure is not decorative, but fundamental to human flourishing.

The comparative case design clarified how place attachment is supported through distinct yet complementary pathways. Prior work has long recognised that both physical and social dimensions contribute to attachment [4,36,93], with some demonstrated contested weight of influence [94,95,96]. This has addressed this debate by showing the interrelated and dual effect of social and physical factors and how they connect to other experiential constructs and measurable features of space within the tested model. Tranquil, nature-rich environments such as the Wooded Zone and EE Park generated attachment by affording restoration and passive co-presence. Students valued these settings for peace, quiet, and connection to nature, confirming the mediating role of restorative experience between physical qualities and attachment. This pattern is consistent with qualitative findings that wild or highly natural settings afford deeper emotional connection, reflection, spiritual values, and place bonding [97,98]. In contrast, social hubs like the Sports Courts Plaza and Lecture Hall Lawn fostered attachment through active interaction and a sense of community, where bonds were built through shared activities and active encounters. This pattern approximates previous findings that both perceived wildness and perceived management of the environment contribute positively to place attachment through distinct experiential pathways, freedom and escape on one hand, and care and security on the other [99]. This implies that designers should aim for environments where different degrees of intervention coexist by integrating patches of unstructured greenery, textural richness, and ecological variety within accessible, well-maintained, and socially active settings. Such a balance allows both solitude and sociability, supporting the dual pathways of restoration and community that underpin lasting attachment to place.

Spaces that lacked both restorative and communal qualities, such as the Memorial Plaza and the Memorial Plaza, consistently recorded the lowest attachment, showing that successful environments must provide at least one pathway, and ideally both in a larger-scale environment like a campus or a neighbourhood. Another notable finding was the negative correlation between visit frequency and place attachment, implying that attachment was stronger toward spaces experienced as distinctive rather than routine. Places used less frequently but associated with rest, reflection, or collective experience appear to hold greater symbolic and affective value than others. This pattern resonates with the idea that attachment is not merely a function of exposure, but of the quality and meaning embedded in spatial experience. Duration of lingering in a place also did not seem to be a deciding factor in all cases. The Wooded Zone was mainly a passage area, but still one of the highest attached places, proving the value of micro-restorative experiences and wild pockets.

Overall, the findings carry important implications for the urban and landscape design of campuses, as well as for other urban environments, such as parks and neighbourhoods. First, they confirm the value of biophilic strategies that integrate naturalistic forms and ecological content into the urban fabric. It also supports the view that greening alone misses the full picture: although green spaces are widely assumed to foster attachment, empirical work shows that the mere presence of green space may not suffice [100]. Our results, which show that structural/aesthetic order and social interaction also play key roles, offer one explanation for these mixed findings, highlighting that it is how green space is experienced and structured, not simply how much there is, that matters.

Second, the significance of both passive and active interaction highlights the need for spatial diversity. Consistent with earlier studies showing that lively public spaces accommodate a spectrum of engagement [42,101], our results add nuance by revealing distinct pathways through which these interactions foster attachment. Mediation analysis showed that passive interaction indirectly enhanced place attachment via restorativeness, while active interaction did so through sense of community. In our case, tranquil co-presence in semi-wild or secluded areas was as valued as active gathering in social hubs. A successful campus or neighbourhood environment, therefore, requires a mosaic of spatial types: open lawns for flexible use, semi-wild wooded retreats, pedestrian promenades for circulation and encounter, and multifunctional plazas. Such complementarity ensures that different modes of attachment—restorative and communal—can coexist within the same setting.

Although previous research has shed light on the positive role of symbolism and cultural identity in developing place attachment in certain contexts [49,50,57,102,103], our case revealed a general aversion or ambivalence to the monumentally designed spaces (namely, the library plaza and memorial plaza). Furthermore, the contrast between the Wooded zone and the Memorial Plaza illustrates how design intentions can diverge from lived experience. Although the Plaza was designed as a symbolic focal point, its rigid monumentalism and hard surfaces yielded some of the lowest ratings across all measures. By contrast, the Wooded zone, despite being largely a circulation space and with minimum design intervention, generated strong restorative and attachment outcomes. This divergence indicates that attachment may not necessarily be supported by symbolic design. Qualities of softness, adaptability, and ecological presence matter more than monumentality. This can be especially the case for campus design, where young people may be less inclined to connect to institutional identity and more towards their personal relationships and opportunities for restoration during stressful academic life [85,87,88,89]. In aesthetic terms, the Wooded zone embodied structural properties such as roughness, gradients, and levels of scale in an unplanned but coherent way, whereas the Plaza suppressed them through formal rigidity.

Although this study focused on environmental aesthetics and visual perception, the principles of naturalistic structure also extend to spatial configuration. Properties such as strong centres, boundaries, and levels of scale may also have a performative role through the organisation of space. For example, boundaries can organise social activity and create comfortable edges for lingering, while strong centres are related to properties of spatial integration. Such an approach complements configurational approaches such as space syntax and movement-based theories, which similarly link spatial structure to social behaviour and accessibility [104,105,106]. Although examining these configurational dimensions lies beyond the scope of this study, future research could integrate Alexander’s generative principles with spatial network analysis and place attachment outcomes to better understand how living structure supports both spatial and functional dimensions of public space.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the operationalisation of wholeness and the 15 properties required significant simplification. Metrics such as fractal dimension and entropy capture aspects of complexity but cannot fully represent the nuances of Alexander’s concepts nor the full range of complexity features. Second, the study was confined to a single campus, which limited its generalizability. Third, relying on photographs for image analysis and external ratings overlooks the multisensory and temporal qualities of place. Despite these constraints, the triangulation of methods strengthened validity, and the findings should be read as exploratory evidence of theoretical links. Future research should extend cross-cultural comparisons, integrate multimodal measures such as soundscapes and movement patterns, and develop richer ways to operationalise structural properties.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that place attachment in public open spaces arises from the interplay of aesthetic–restorative qualities and social dynamics. By integrating Alexander’s theory of living structures with restorative frameworks, it extends place attachment theory beyond simple greenness metrics to show that structural order, complexity, and perceived wholeness contribute to meaningful bonds with place.

H1 proposed that place attachment would be jointly predicted by aesthetic–restorative qualities and social factors. The results supported this: both domains significantly predicted attachment, with perceived restorativeness and sense of community emerging as the strongest predictors in the regression model. Comparisons across campus settings further showed that the relative influence of physical versus social qualities depended on each place’s design characteristics and social activity profile. H2 proposed that places affording higher social interaction would yield stronger place attachment. This hypothesis was also supported, with mediation analyses revealing that passive interaction enhanced attachment indirectly through restorativeness, whereas active interaction did so through sense of community. These findings suggest distinct but complementary psychological routes linking social experience to attachment. H3 predicted that spaces exhibiting greater structural richness—quantified through image-based metrics—would correspond to higher perceived aesthetic–restorative qualities. This was partially supported: correspondence was strongest in settings high in natural content, and aesthetic evaluations showed strong convergence between users and non-users, indicating shared perceptual sensitivity to structural and naturalistic order.

These findings carry implications for urban and landscape design practice that aims to support emotionally sustainable and nourishing public spaces. They support design strategies that preserve semi-wild character, feature detail and visual richness, and provide varied affordances by accommodating both retreat and encounter. It also highlights that successful open spaces depend less on institutional symbolism or formal monumentality than on the subtle integration of natural complexity, spatial hierarchy, and social affordances for different modes of social interaction.

While the study was limited to a single campus context, its approach offers a transferable model for evaluating how naturalistic and social affordances interact in other institutional or urban settings. Future work could extend these findings through longitudinal and cross-cultural studies, and by integrating configurational analysis, such as spatial analyses, to better understand how spatial organisation supports restorative and communal experience.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/architecture5040114/s1, 1. Image analysis Python codes; 2. Photographs used in image analysis; 3. Observation raw data; 4. Independent raters’ survey data.

Author Contributions

Data curation, S.A.-A.; formal analysis, S.A.-A.; investigation, S.A.-A.; methodology, S.A.-A.; project administration, G.İ. and S.A.-A.; resources, S.A.-A.; software, S.A.-A. and N.A.-A.; supervision, G.İ.; validation, G.İ. and S.A.-A.; visualization, S.A.-A.; writing—original draft, S.A.-A.; writing—review & editing, S.A.-A. and G.İ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The student online survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Technical University (approval code: 613; approval date: 13 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants prior to data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical restrictions, individual survey responses are not publicly available. Anonymized aggregated data, Python analysis scripts, and other Supplementary Materials are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors used generative AI tools (ChatGPT, version GPT-5 and Grammarly Premium v1.2.211.1787) for language refinement under full author oversight; no AI was used for data generation, analysis, or interpretation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Operationalization of Constructs

Appendix A.1. Variables and Question Items Used in the Student Survey

| Variable Item | Definition | Item | Scale Measurement | Sources of Questionnaire Items/Adaptation |

| familiarity | ||||

| Recognition | eligibility check | “Do you recognize the place depicted in the images?” | yes/no | |

| “Have you been to this place at least once during your time on campus?” | yes/no | |||

| Frequency of Use | Parallel measure to “length of residence”, which is usually applied in SoP research in a residential context | “How often do you visit this place when you are on campus?” | 5-item

| |

| Proximity | The perceived distance from where students usually attend their educational activities | “How close is this place to your faculty building (or the building you use the most)?” |

| |

| Place attachment | ||||

| Place Meaning | the meanings associated with the place | “What comes to mind when you think of this place?” | open-ended | [30] |

| “If you could change one thing about this place what would it be?” | open-ended | |||

| “Which of the following do you associate with this location? (you can choose more than one)” |

| |||

| Place attachment (6 items): | ||||

| Place identity | The value of place in the identification process | “This open space on campus means more to me than other places on campus.” | 5-item:agreement | [30] |

| “This open space reflects who I am as a student.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “I feel very attached to this open space compared to other places on campus.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| Place dependence | refers to the useful value (services, aesthetic) that a place has in comparison to other places to satisfy an individual’s specific goals and desired activities | “This open space is the best place on campus for the activities I enjoy.” | 5-item:agreement | [30] |

| “I feel happiest when I am in this open space compared to other areas on campus.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “No other place on campus can compare to this open space.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| Environmental perception | ||||

| Perceived naturalness * | the degree to which a scene is felt to be natural, whether through its explicit natural content or through its overall visual impression and atmosphere | “This place feels predominantly natural rather than artificial.” | 5-item:agreement | [21,70,99,107,108,109,110] |

| explicit nature presence | “This place has plentiful and diverse natural elements such as vegetation and water.” | 5-item:agreement | ||

| Life quality | “This place appears vibrant and life-like.” | 5-item:agreement | ||

| perceived wildness | “This open space seems more wild and untamed than overly planned.” | 5-item:agreement | ||

| nature connectedness | “Spending time here makes me feel connected to the natural environment.” | 5-item:agreement | ||

| Perceived Restoration | perceptions of being away, fascination, extent, and compatibility that support psychological restoration | “This place helps me clear my mind and escape daily demands.” | 5-item:agreement | [91] |

| “This place has features that captivate my interest and curiosity.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “This place is spacious and offers opportunities for exploration in many directions.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “This place feels organized and easy to navigate, which suits my needs.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| Social Interaction | ||||

| Active Social Interaction * | active interactions include engagement with other people in the place | “I enjoy spending time with my friends and socializing here.” | 5-item:agreement | [40,42,111,112] |

| “This space is well-suited for organized group activities or events.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “I often see people interacting actively (e.g., talking, playing, collaborating) in this space.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| Passive Social Interaction * | observation of social life without direct participation | “This is a good place to relax and be alone when I need to.” | 5-item:agreement | |

| “This space offers comfortable areas to sit and observe the surroundings.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “I enjoy observing other people using this space.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| Sense of Community * | supporting forming social network and trust, and local identity | “This space provides opportunities to build and strengthen friendships.” | 5-item:agreement | [10,44] |

| “This place is a good representation of ITU student community.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| “Spending time in this space makes me feel more connected to the campus community.” | 5-item:agreement | |||

| Type of activity | “What is the primary activity you engage in when you are here? (you can choose multiple)” |

| ||

| Person-based factors | ||||

| age | “What is your age group?” |

| ||

| gender | “What is your gender?” |

| ||

| years studying on campus | “How many years have you been enrolled as a student in ITU?” |

| ||

| faculty | “What faculty are you associated with?” | open ended | ||

| Level of Education | “Which applies to you?” |

| ||

| average time spent on campus | “On average how much time do you spend at campus during the academic semester?” |

| ||

| residence | “do you reside on campus?” | yes/no | ||

| * Novel Variables developed from the theoretical framework. | ||||

Appendix A.2. Variables and 5-Point Semantic Differential Items Developed from the Theory of Living Structures

| Construct | Variable | Semantic Pair | Prompt | Reference Quote from The Nature of Order |

| Sense of Wholeness * | Harmony and Unity | Fragmented and disjointed ↔Unified and harmonious | Consider whether this space feels like a cohesive whole or if it seems fragmented and disjointed | “Wholeness is the overriding structure which exists in space, and it is from this wholeness that the life of the space emerges. Every part works together to enhance the whole.” |

| Sense of Life | Lifeless and dull ↔Vibrant and full of life | Reflect on whether this space feels vibrant and alive, or if it seems lifeless and unengaging | “The degree of life in a structure depends on its wholeness. It is the feeling that every part contributes to the creation of something that feels vibrant and alive.” | |

| Beauty | Unattractive and ordinary ↔Beautiful and inspiring | Think about whether this space inspires you with its beauty or if it feels plain and unattractive | “True beauty arises from wholeness, when every element of a space works together to create a harmonious and inspiring whole that resonates deeply with us.” | |

| Emotional Resonance | Emotionally distant ↔Emotionally engaging | Does this space evoke an emotional connection, or does it feel distant and impersonal? | “The spaces that move us most deeply are those which resonate emotionally with our own sense of being, creating a profound connection between us and the place.” | |

| Comfort and Warmth | Cold and uninviting ↔Warm and inviting | Consider whether this space feels welcoming and comfortable, or if it feels cold and uninviting | “A living structure radiates warmth, creating an emotional atmosphere that makes us feel safe, comfortable, and at home.” | |

| Timeless Quality | Temporary and forgettable ↔Timeless and memorable | Reflect on whether this space has a timeless quality that makes it memorable, or if it feels temporary and forgettable | “A timeless quality emerges when a space reflects the deep structure of wholeness that has been present in beautiful places throughout history, making it unforgettable.” | |

| Perceived Order (from the 15 fundamental properties) * | Levels of Scale | Simple and monotonous ↔Rich and varied | Think about whether this space includes a variety of elements of different sizes and scales, or if it feels monotonous and simple | “The strength of any centre depends on the centres of the next smaller size that support it and help it intensify. The richness of this structure derives from the interweaving of levels of scale.” |

| Strong Centres | No clear focal points ↔Well-defined focal points | Consider whether there are clear focal points in this space that attract your attention and feel important, or if no part of the space stands out | “A strong centre is a configuration of field-like effects that draws the observer’s attention and creates a point of focus, giving structure to the whole.” | |

| Boundaries | Undefined and vague ↔Clearly defined | Reflect on how well-defined the edges of this space are—do they make the space feel structured and contained, or do they seem vague and undefined | “Boundaries strengthen a centre by differentiating it from what surrounds it, while simultaneously connecting it to the larger whole.” | |