Reviving Territorial Identity Through Heritage and Community: A Multi-Scalar Study in Northwest Tunisia (El Kef and Tabarka Cities)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context as a Basis for Local Collective Identity Interpretation

2.1. El Kef’s Heritage

2.2. Tabarka’s Heritage

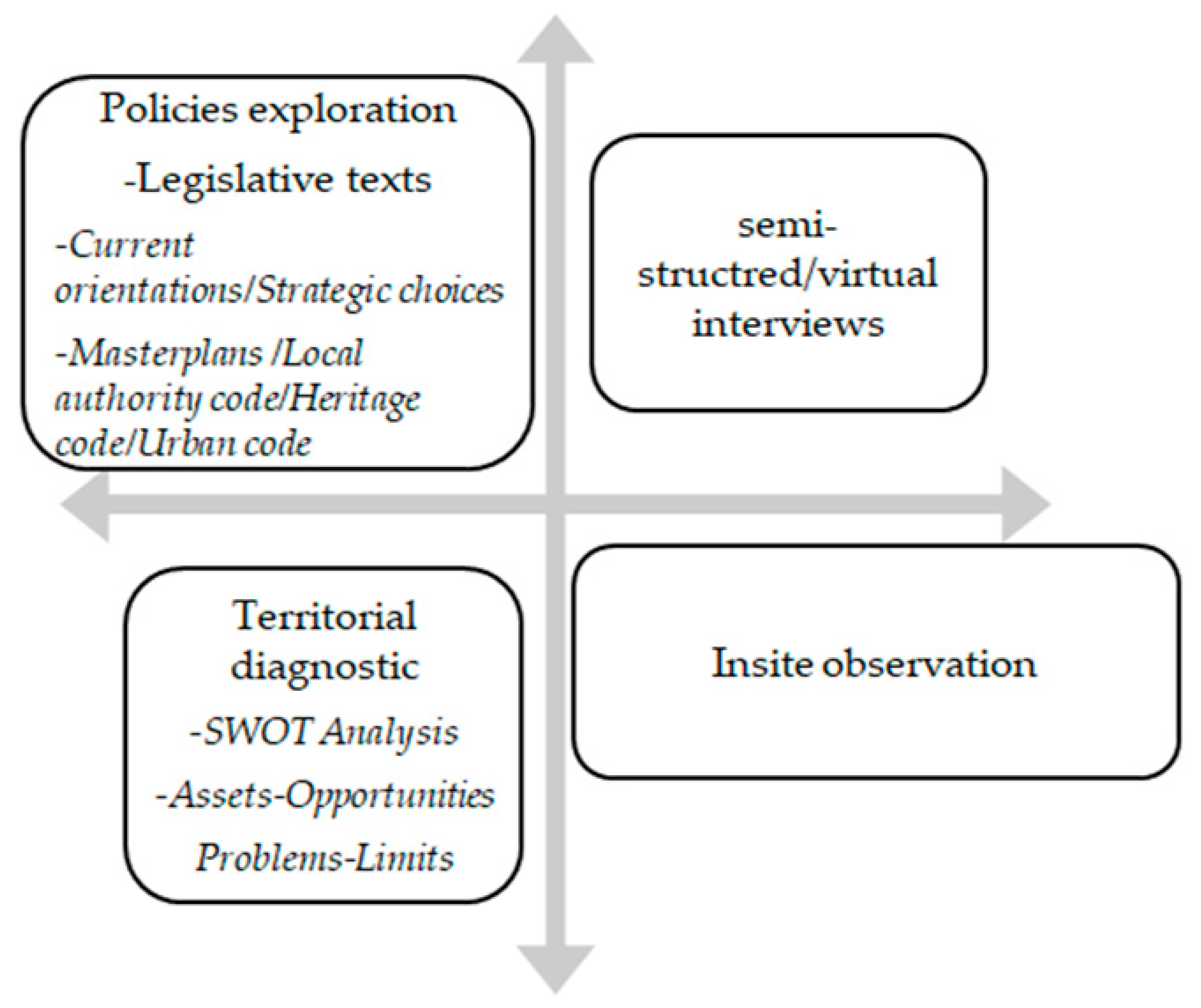

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Challenges of Cultural Heritage in City Centres of El Kef and Tabarka

4.1.1. El Kef: Abandonment and Desertion of the Centre

4.1.2. Tabarka: Densification of the Centre on the Seafront

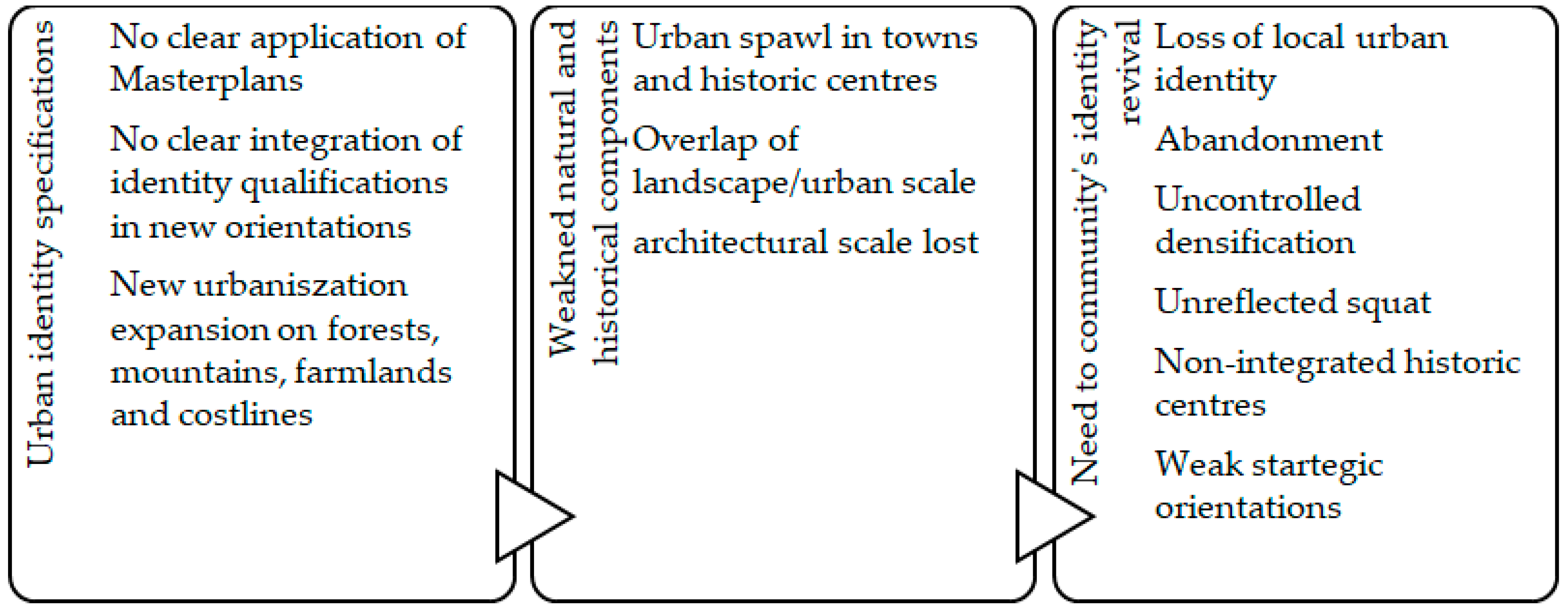

4.2. Dysfunction in Architectural and Urban Planning Policy

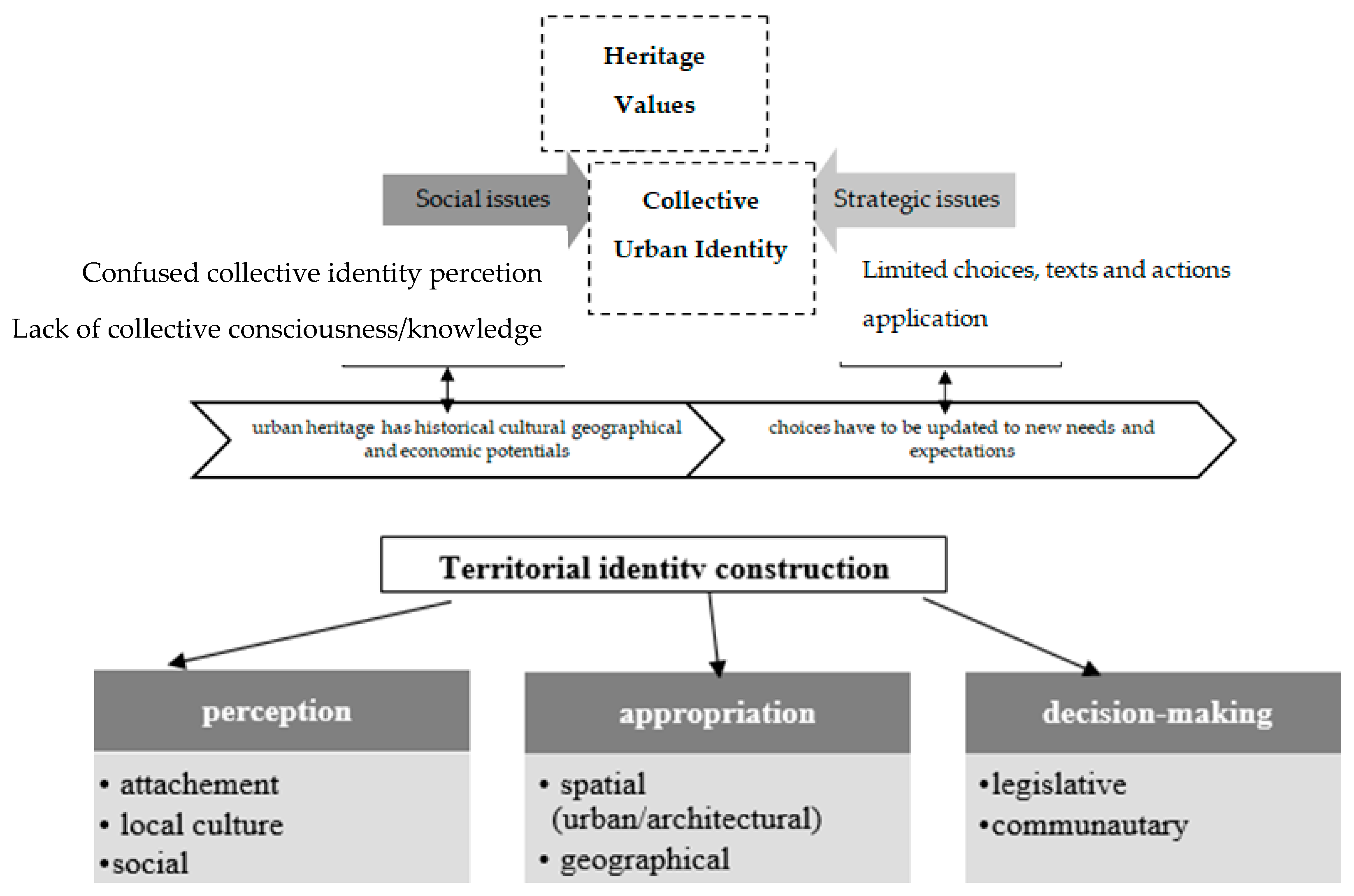

5. Discussion

- -

- Complexity and Diversity: Territorial identity is multifaceted, influenced by cultural, historical, and social factors.

- -

- Methodological Issues: Developing effective methodologies for assessing territorial identity requires balancing qualitative and quantitative approaches, often necessitating extensive fieldwork and community engagement. Cultural landscapes and heritage help people connect physically and emotionally, as people often feel tied to a place through its unique qualities that symbolise how they define themselves.

5.1. Denial of Historical Identity

5.2. Lack of Knowledge and Investment in Traditional Building Techniques

5.3. Inclusive Governance as a Strategic Challenge

5.4. Recommendations for the Revival of Northwest’s Territorial Identity

5.4.1. Development of a New Proximity Heritage Artefact

5.4.2. Restructuring Urban Development

5.4.3. Revised Policy: Towards Adaptive Governance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDA | Master Plan for the Planning and Development SchémaDirecteurd’Aménagement |

Appendix A

Interview Questions

- -

- Did you know that the El Kef and Tabarka regions contain important archaeological sites?

- -

- If so, do you know the distance between the historic centre and the surrounding archaeological sites?

- -

- What are the problems blocking our enhancement of the city’s cultural and built heritage?

- -

- Does the city preserve its cultural and architectural identity?

- -

- If so, how? If not, why?

- -

- Do you have any suggestions about how to strengthen the promotion of the city’s social, urban, and cultural development?

- -

- If you could choose the type of construction of your house, would you prefer the solid slab or the red-tiled roofs?

- -

- Do you suggest a strategy for enhancing the city and its historic centre?

- -

- Are past and current initiatives sufficient to promote the image of the cities of El Kef and Tabarka as distinguished tourist and cultural destinations?

References

- Bailly, A. Espace géographique et espacevécu: Vers de nouvelles dimensions de l’analysespatiale. In Espace et Localisation; Paelinck, J.H.P., Sallez, A., Eds.; Économica: Paris, France, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bossé, M. La question de l’identitéengéographieculturelle. Géogr. Cult. 1999, 31, 115–126. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/gc/10466 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Coco, C.; Klein, J.L. Identity and Territory in the Reconstruction of the Viger Malecite Community. Cah. Géogr. Qué. 2012, 56, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiki, L. Regional Development in Tunisia: The Consequences of Multiple Marginalization; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4141104/regional-development-in-tunisia/4949728/ (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Mautner, T. Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd ed.; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2005; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, A. Temps et Sociétés. In Introduction à la Géographie Humaine; Bailly, A., Beguin, H., Scariati, R., Eds.; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi, A. Formalisation of the Teleomorphic Identity of Facades: Case of Residential Buildings Ennacer City, Tunis, 1990–2015. Ph.D. Thesis, National School of Architecture and Urbanism (ENAU), Tunis, Tunisia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Règles de L’art; Éditions de Minuit: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. Misère de L’historicisme; Pocket: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Verdier, P. Le Projet Urbain Participatif: Apprendre à Faire la Ville Avecses Habitants; Adels/Yves Michel: Gap, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Di Méo, G. Subjectivité, socialité, spatialité: Le corps, cetimpensé de la géographie. Ann. Géogr. 2010, 675, 466–491. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/revue-annales-de-geographie-2010-5-page-466?lang=fr (accessed on 6 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Souissi, M. Les ressources du Nord-Ouest tunisien dans les stratégies du pouvoir. In Actes du Colloque du Centre de Publication Universitaire; CPU: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Faleh, M.; Gharbi, A.; Ben Fatma, N. Tunisia’s El Kef City Is Rich in Heritage: Centuries of Cultural Mixing Give It a Distinct Identity. The Conversation, 8 April 2024. Available online: https://theconversation.com/tunisias-el-kef-city-is-rich-in-heritage-centuries-of-cultural-mixing-give-it-a-distinct-identity-224518 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Bouchoucha, A. Centre de Réflexion Stratégique Pour Le Développement du Nord-Ouest. In Actes Premier Forum Annuel Perspectives du Développement Régional dans La Tunisie Post-Révolutionnaire; Turess: Tunis, Tunisia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Belhedi, A. Les dispariés régionales en Tunisie. Défis et enjeux. In Les Conférences de Beit al-Hikma 2017–2018; Beit al-Hikma: Tunis, Tunisia, 2019; pp. 7–62. [Google Scholar]

- MEHAT. Master Plan for the Planning and Development of the Governorate of Jendouba by 2030; General Directorate of Regional Planning: Tunis, Tunisia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MEHAT. Master Plan for the Planning and Development of the Governorate of El Kef; Ministry of Housing and Equipment: Tunis, Tunisia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ltifi, A. An Uncertain Urban Future for Tunis? UrbanAfrica.Net. 2013. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opensecurity/uncertain-future-for-tunis. (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Ayadi, M.; El Lahga, A.; Chtioui, N. Analyse de la pauvreté et des inégalités en Tunisie entre 1988 et 2001: Une approche non monétaire. In Proceedings of the 5th PEP Research Network General Meeting, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 18–22 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère du Développement Régional et de la Planification; InstitutTunisien de la Compétitivité et des Études Quantitatives. Indicateur de Développement Régional: Étude Comparative en Terme de Développement Régional; Tunis, Tunisia. 2024. Available online: https://www.cgdr.nat.tn/upload/files/13.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Activités Techniques. Available online: https://www.inp2020.tn/activites-de-linp/activites-techniques/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Code of Archaeological, Historical and Traditional Arts Heritage, 2001–2025. Available online: https://www.jurisitetunisie.com/tunisie/codes/patri/patri1025.htm (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- UNESCO, ICH. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2024 ed.; Data for the Sustainable Development Goals; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/conservation-cultural-heritage (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Sub-Mediterranean Committee Announcements. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2012-Izmir-Presentation_Faika-Bejaoui.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Projet Bab Souika-Halfaouine. Available online: http://www.commune-tunis.gov.tn/publish/content/article.asp?id=200 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Beschaouch, A. Le territoire de Sicca Veneria (El-Kef), nouvelle Cirta, enNumidieproconsulaire (Tunisie). C. R. Séances Acad. Insc. Belles Lett. 1981, 125, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IACE. Annual Report on Regional Competitiveness; Institut Arabe des Chefs d’Entreprises: Tunis, Tunisia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gourdin, P. Tabarka. Histoire et Archéologie d’un Préside Espagnol et d’un Comptoir Génoisen Terre Africaine (XVe–XVIIIe siècle); École Française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Claval, P. Géographie Culturelle: Une Nouvelle Approche des Sociétés et des Milieux; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Places and Identity: A Sense of Place. In A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalisation; Massey, D., Jess, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press/Open University: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 87–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mommaers, P. Marcel Proust, Esthétique et Mystique: Une Lecture d’À la Recherche du Temps Perdu; Éditions du Cerf: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaud, J.-P.; Grosjean, M. L’espace Urbain en Méthodes; Parenthèses: Marseille, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Land Use and Urban Planning Code, Tunisie. 2011. Available online: https://cgdr.nat.tn/upload/files/18.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, P. An Austrian Contribution in the Theory of Territory. Rev. Écon. Rég. Urbaine 2001, 2, 229–240. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/revue-d-economie-regionale-et-urbaine-2001-2-page-229 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Morin, Y. University in Its Territories: Higher Education and Research as Territorial Operator. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aldana, A.M.; El Fassi, S. Tackling Regional Inequalities in Tunisia; ECDPM Briefing Note 84; European Centre for Development Policy Management: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://www.economie-tunisie.org/sites/default/files/bn-84-tackling-regional-inequalities-tunisia-ecdpm-2016.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Available online: https://chaexpert.com/documents/Code%20des%20Collectivit%C3%A9s%20Locales.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Tabarka: Le Projet Costa Coralis en Quête de Soutien Stratégique. Available online: https://africanmanager.com/tabarka-le-projet-costa-coralis-en-quete-de-soutien-strategique (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Programme d’Aménagement du Projet. Available online: https://www.costa-coralis.com (accessed on 24 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gharbi, A.; Faleh, M.; Fatma, N.B. Reviving Territorial Identity Through Heritage and Community: A Multi-Scalar Study in Northwest Tunisia (El Kef and Tabarka Cities). Architecture 2025, 5, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040104

Gharbi A, Faleh M, Fatma NB. Reviving Territorial Identity Through Heritage and Community: A Multi-Scalar Study in Northwest Tunisia (El Kef and Tabarka Cities). Architecture. 2025; 5(4):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040104

Chicago/Turabian StyleGharbi, Asma, Majdi Faleh, and Nourchen Ben Fatma. 2025. "Reviving Territorial Identity Through Heritage and Community: A Multi-Scalar Study in Northwest Tunisia (El Kef and Tabarka Cities)" Architecture 5, no. 4: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040104

APA StyleGharbi, A., Faleh, M., & Fatma, N. B. (2025). Reviving Territorial Identity Through Heritage and Community: A Multi-Scalar Study in Northwest Tunisia (El Kef and Tabarka Cities). Architecture, 5(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040104