Placemaking and the Complexities of Measuring Impact in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Public and Community Housing: From Theory to Practice and Lived Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Placemaking in Public and Community Housing

1.2. Aotearoa New Zealand Housing Context

“New Zealand’s housing history has had its highs and lows. There were times when the majority had adequate housing, strong communities, and affordable living costs, with housing taking up about a third of household income. But New Zealand and the world have changed significantly in recent decades. More families are finding it harder to live securely and affordably. Supporting them is a key challenge, which community housing organisations have taken up”.[24]

“Community housing providers believe in community building, which means creating mixed, diverse, and inclusive developments and delivering homes, not just houses… The most successful community-led developments deliberately include shared spaces, community hubs, and ‘bump spaces’ (a public space to promote community connection), to support residents in getting to know each other in mixed-tenure environments”.[24]

1.3. Structure of the Paper

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Partnership and Multimethodological Approach

2.2. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. CHPs’ Change Theories About Placemaking and Community Infrastructure

“For Central, it was very much a placemaking exercise, so we had a lot of community engagement, placemaking experts, literature, and we had… IAP2 (The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) is a global organisation dedicated to promoting and enhancing public participation in decision-making processes. Established in 1990, IAP2 serves individuals, governments, institutions, and other entities that affect the public interest. Its mission is to advance public participation through education, advocacy, and the development of best practices.) [training]… which was really successful. We wanted the tenants to feel like they were an integral part of making their homes—that was probably the top priority. And they were involved in every stage of the design. We did make changes every time based on that”.[45]

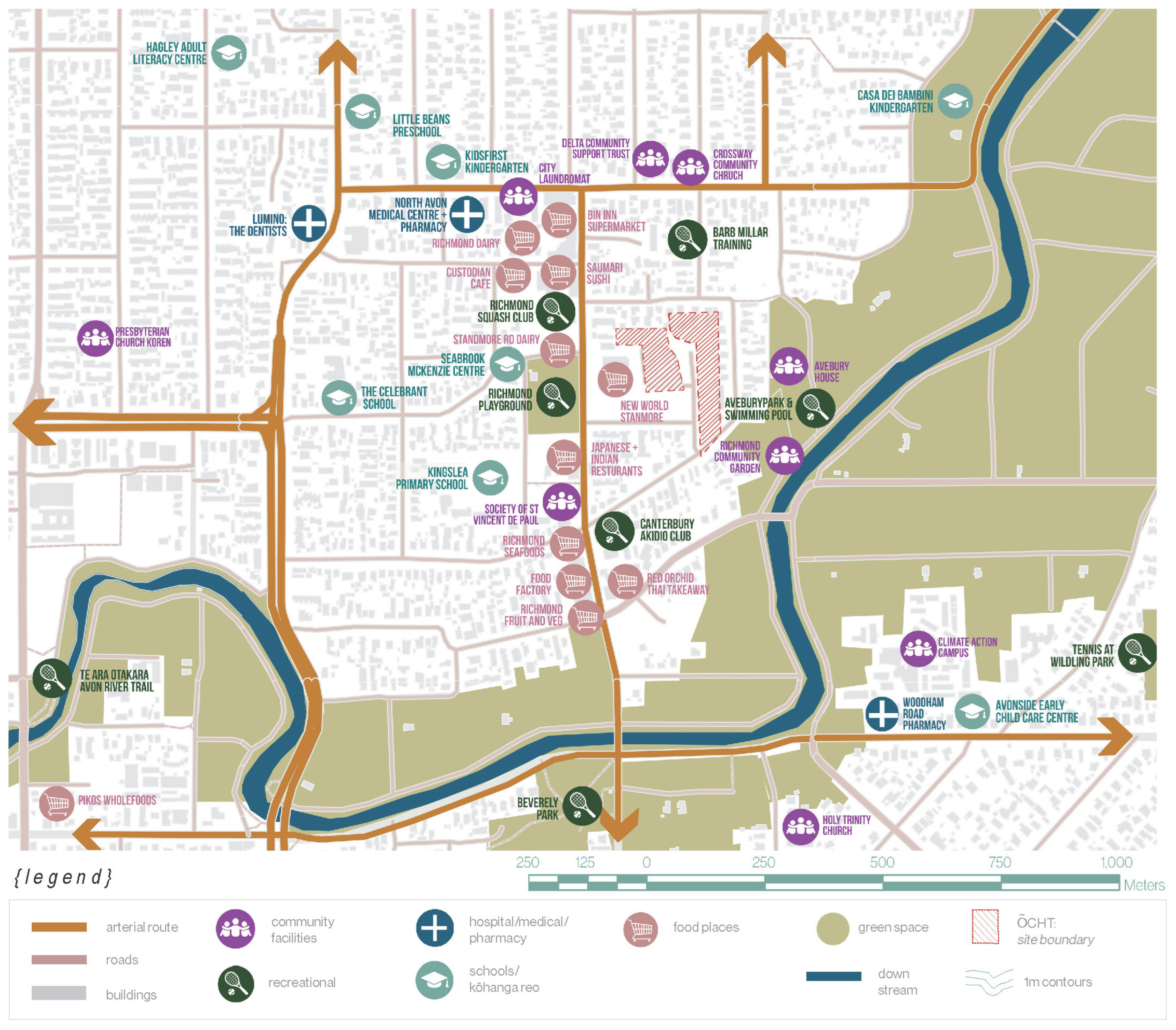

“Our model is that we don’t include community services. Our model is that we work with our tenants so they reach out into what is around them. What we do, it’s a little bit of the navigation. We will know of all the services that are available to them, be it doctors, dentists, all the usual, parks, schools, and we will advise people”.[47]

“The structure… is so much to get your head around because there’s the church side and then there’s the army side, and then you’ve got the chaplaincy which is a different part of that as well. So, this is another really awesome thing about Salvation Army is just the resources we can pull from… We’ve got like chaplaincy and stuff like that and these corps offices, [which are] in that area to support not only our tenants but just the local congregation and stuff like that as well. Run programmes, do English classes and just be there in general to support”.[48]

“We choose our locations carefully so that people aren’t at a loss when we build out because they can walk to a park. They can walk to the library. They can walk to the school yard. And hear the water, you know, the ocean, so I guess the point would be we take every location very seriously and weigh up that series of factors”.[49]

3.2. CHP Case Study Sites

3.3. Insights from Tenant Survey Responses

3.4. Tenant Experiences of Safety

“Moving about the place… I always think, should I take my cell phone with me because you’re never sure when you’re going to encounter anyone who’s disorderly or drunk or having a domestic dispute”.[52]

3.5. Tenant Experiences of Belonging and Connectedness

“When I go to [food distribution event] or I go to the computer room and everyone’s chatty… there’s not one person that I haven’t got a response of ‘Hi’ or anything after I said it to them”.[62]

“Just generally to see the people from different cultures and exchange views and everything. Quite often they have international cuisines, you can try different food. It is very well organised I must say, this of course is thanks to Council”.[64]

“Everything’s accessible and the neighbours are all friendly and everyone makes an effort to make it nice… Everyone says hi when you walk past but leaves you alone if you want… if you need help a neighbour… yeah”.[67]

“Well, we’ve all got [an illness], and we can all relate to each other. We don’t dwell on it if you’re not feeling too well one particular day, you can still go there’s no rules, you don’t have to paint. If you want to just sit there and talk you can. It’s really quite therapeutic. We’ve got a good bonding. A sense of belonging there”.[58]

4. Discussion

4.1. Aligning Provider Intentions with Tenant Realities

4.2. Study Limitations

4.3. Placemaking Decision Framework

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For more information about the PH&UR Research Programme, visit the following website: https://www.sustainablecities.org.nz/our-research/current-research/public-housingurban-regeneration-programme) (accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| 2 | An accessibility index is a tool used to measure how easily people can reach desired services or destinations, such as jobs, schools, or healthcare facilities, within a specific area; it is a way to gauge how convenient and reachable important places are for individuals in a community. |

| 3 | In a separate paper, Witten et al. [37] give a fuller report on the placemaking practices and related decision-making of these four CHPs and two urban regeneration pro-grammes. |

| 4 | To manage participant burden across the many projects undertaken for the PH&UR Research Programme, tenant participants who agreed to participate in further re-search after taking the survey were approached for no more than two additional studies. This means that a limited number of participants were available for each study, and the authors were unable to interview tenants from all housing providers partnered with in this research. |

| 5 | In a separate paper entitled “Like a family without being a family”: Social connected-ness between social housing tenants in Aotearoa New Zealand, which is currently under review, Chisholm et al. will present findings from a template analysis of the full dataset of tenant interviews conducted across six public and community housing sites, using both deductive and inductive coding to explore tenants’ experiences of social connectedness. |

References

- Kromhout, S.; van Ham, M. Social Housing: Allocation. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Smith, S.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 284–388. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, E.; Olin, C.; Randal, E.; Witten, K.; Howden-Chapman, P. Placemaking and public housing: The state of knowledge and research priorities. Hous. Stud. 2023, 39, 2580–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, P.J.; Ellery, J.; Borkowsky, M. Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2021, 4, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijen, G.; Piracha, A. Future directions for social housing in NSW: New opportunities for ‘place’ and ‘community’ in public housing renewal. Aust. Plan. 2017, 54, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, A.; Smith, C.; O’Sullivan, K.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Gros, L.L.; Dohig, R.K. Housing Tenure and Subjective Wellbeing: The Importance of Public Housing. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C. The Experience of Displacement on Sense of Place and Well-being. In Sense of Place, Health and Quality of Life; Williams, A., Eyles, J., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2008; pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mee, K. A Space to Care, a Space of Care: Public Housing, Belonging, and Care in Inner Newcastle, Australia. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2009, 41, 842–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. “It was like leaving your family”: Gentrification and the impacts of displacement on public housing tenants in inner-Sydney. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2017, 52, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, G.; Ruel, E.; Anderson, A.; Reitzes, D.C.; Oakley, D. Sense of Place among Atlanta Public Housing Residents. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, P. Displacement and estate demolition: Multi-scalar place attachment among relocated social housing residents in London. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 1686–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, M.; Rogers, D. Inhabitance, place-making and the right to the city: Public housing redevelopment in Sydney. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2014, 14, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.; Collins, F.L.; Kearns, R. ‘It is the People that Have Made Glen Innes’: State-led Gentrification and the Reconfiguration of Urban Life in Auckland. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinholz, D.L.; Andrews, T.C. Change theory and theory of change: What’s the difference anyway? Int. J. STEM Educ. 2020, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, K.; Viggers, H.; Howden-Chapman, P. Severe Housing Deprivation in New Zealand, 2018; University of Otago: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, A. Improving Well-Being through Better Housing Policy in New Zealand (Renforcer le bien-être en améliorant la politique du logement en Nouvelle Zélande); No. 1565; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Early, L.; Ombler, J. Cities in New Zealand: Preferences, Patterns and Possibilities; Steele Roberts: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Olin, C.V.; Berghan, J.; Thompson-Fawcett, M.; Ivory, V.; Witten, K.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Duncan, S.; Ka’ai, T.; Yates, A.; O’Sullivan, K.C.; et al. Inclusive and collective urban home spaces: The future of housing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2022, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey University. Community Acceptance of Medium Density Housing Development; Massey University: Porirua, New Zealand, 2020; Available online: https://d39d3mj7qio96p.cloudfront.net/media/documents/ER57_Community_acceptance_of_MDH_development.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- StatsNZ. 2023 Census Severe Housing Deprivation (Homelessness) Estimates; Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024.

- Barrett, P. Intersections between housing affordability and meanings of home: A review. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2023, 18, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, A.; Varley, A. Geographies of Home. Cult. Geogr. 2004, 11, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.; Allport, T.; Kaiwai, H.; Harker, R.; Osborne, G.P. Māori perceptions of ‘home’: Māori housing needs, wellbeing and policy. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2021, 17, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangata, T.K.T. Right to a Decent Home. Human Rights Commission, n.d. Available online: https://tikatangata.org.nz/human-rights-in-aotearoa/right-to-housing (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- CHA. Insight Report—Community Housing Providers: Examining the Role of Community Housing Providers and CHA; Community Housing Aotearoa: Wellington, New Zealand, 2025. Available online: https://communityhousing.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Insight-Report-Edition-1-Community-Housing_May-2025.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- HUD. Income-Related Rent Subsidy. Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. 2024. Available online: https://www.hud.govt.nz/funding-and-support/income-related-rent-subsidy? (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- CPAG; PHF. A People’s Review of Kāinga Ora: In Defence of Public Housing; Child Poverty Action Group: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- MSD. Housing Register. Ministry of Social Development. 2024. Available online: www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/housing/housing-register.html#latestresultsdecember20241 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Rangiwhetu, L.; Pierse, N.; Chisholm, E.; Howden-Chapman, P. Public Housing and Well-Being: Evaluation Frameworks to Influence Policy. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, E.; Pierse, N.; Howden-Chapman, P. Perceived benefits and risks of developing mixed communities in New Zealand: Implementer perspectives. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 15, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G. Building the New Zealand Dream; Dunmore Press with the assistance of the Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, B. We Call it Home: A History of State Housing in New Zealand; Reed: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, E.; Pierse, N.; Howden-Chapman, P. What is a Mixed-tenure Community? Views from New Zealand Practitioners and Implications for Researchers. Urban Policy Res. 2021, 39, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sarkissian, W. Housing as If People Mattered: Site Design Guidelines for the Planning of Medium-Density Family Housing; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Randal, E.; Logan, A.; Penny, G.; Teariki, M.A.; Chapman, R.; Keall, M.; Howden-Chapman, P. Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants—A Scoping Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUD. Public Housing Quarterly Report. Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. 2023. Available online: https://www.hud.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Documents/Public-Housing/HQR-Mar23-web-V2.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- MSD. Briefing to the Associate Minister—Social Development and Employment: Housing Responsibilities; The Ministry of Social Development: Welington, New Zealand, 2023.

- Witten, K.; Olin, C.V.; Logan, A.; Chisholm, E.; Randal, E.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Leigh, L. Placemaking for tenant wellbeing: Exploring the decision-making of public and community housing providers in Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 8, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, G.; Logan, A.; Olin, C.V.; O’Sullivan, K.C.; Robson, B.; Pehi, T.; Davies, C.; Wall, T.; Howden-Chapman, P. A Whakawhanaungatanga Māori wellbeing model for housing and urban environments. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2024, 19, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teariki, M.A.; Leau, E. Understanding Pacific worldviews: Principles and connections for research. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2024, 19, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.; Carr, P.A.; Scott, N.; Lawrenson, R. Structural disadvantage for priority populations: The spatial inequity of COVID-19 vaccination services in Aotearoa. N. Z. Med. J. 2022, 135, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, J.; Pearson, A.L.; Lawrenson, R.; Atatoa-Carr, P. Defining general practitioner and population catchments for spatial equity studies using patient enrolment data in Waikato, New Zealand. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 115, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R. Analyzing and Interpreting Data from Likert-Type Scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.H.B. Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- TTM Representative A. Interview with TTM Representative A. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Representative B. Interview with TTM Representative B. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ŌCHT Representative. Interview with ŌCHT Representative. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- SASH Representative. Interview with SASH Representative. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- DHT Representative. Interview with DHT Representative. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant A, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant A. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant B, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant B. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant C, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant C. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant I, resident of Daniell Street. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant I. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant J, resident of Daniell Street. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant J. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant K, resident of Daniell Street. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant K. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ŌCHT Tenant Participant A, resident of Gowerton Place/Whakahoa Village. Interview with ŌCHT Tenant Participant A. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ŌCHT Tenant Participant B, resident of Gowerton Place/Whakahoa Village. Interview with ŌCHT Tenant Participant B. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ŌCHT Tenant Participant C, resident of Gowerton Place/Whakahoa Village. Interview with ŌCHT Tenant Participant C. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ŌCHT Tenant Participant D, resident of Gowerton Place/Whakahoa Village. Interview with ŌCHT Tenant Participant D. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant D, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant D. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant E, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant E. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant F, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant F. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant G, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant G. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant H, resident of Central Park Apartments. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant H. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant L, resident of Daniell Street. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant L. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TTM Tenant Participant M, resident of Daniell Street. Interview with TTM Tenant Participant M. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ŌCHT Tenant Participant E, resident of Gowerton Place/Whakahoa Village. Interview with ŌCHT Tenant Participant E. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Walk Lee, J.H.; Tan, T.H. Neighborhood Walkability or Third Places? Determinants of Social Support and Loneliness among Older Adults. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2023, 43, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboshima, Y.; McIntosh, J. The Impact of Housing Environments on Social Connection: An Ethnographic Investigation on Quality of Life for Older Adults with Care Needs. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2023, 38, 1353–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, V.; Dines, N.; Gesler, W.; Curtis, S. Mingling, Observing, and Lingering: Everyday Public Spaces and Their Implications for Well-Being and Social Relations. Health Place 2008, 14, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; March, T.L. An Urban Community-Based Intervention to Advance Social Interactions. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; March, T.L.; Bontempo, B.D. Community-Initiated Urban Development: An Ecological Intervention. J. Urban Health. 2007, 84, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossey, E.; Harvey, C.; McDermott, F. Housing and Support Narratives of People Experiencing Mental Health Issues: Making My Place, My Home. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, L.; Randal, E.; Logan, A.; Witten, K.; Olin, C.V.; Chisholm, E.; Howden-Chapman, P. Cultivating Wellbeing: Healing Effects of an Urban Māra Kai (Community Garden) in Community Housing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Local Environ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, S.; Gray, T.; Ward, K. Enhancing Urban Nature and Place-Making in Social Housing through Community Gardening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 72, 127586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L.; Lietz, C.A. Benefits and Risks for Public Housing Adolescents Experiencing Hope VI Revitalization: A Qualitative Study. J. Poverty 2008, 12, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tually, S.; Skinner, W.; Faulkner, D.; Goodwin-Smith, I. (Re)Building Home and Community in the Social Housing Sector: Lessons from a South Australian Approach. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, E.; McKerchar, C.; Thompson, L.; Berghan, J. Māori Experiences of Social Housing in Ōtautahi Christchurch. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2023, 18, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviten-Reid, C.; Lake, A. Building Affordable Rental Housing for Seniors: Policy Insights from Canada. J. Hous. Elder. 2016, 30, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Matsuoka, R.H.; Huang, Y.-J. How Do Community Planning Features Affect the Place Relationship of Residents? An Investigation of Place Attachment, Social Interaction, and Community Participation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Z. The Characteristics of Leisure Activities and the Built Environment Influences in Large-Scale Social Housing Communities in China: The Case Study of Shanghai and Nanjing. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, R.L.; Sullivan, W.C.; Kuo, F.E. Where Does Community Grow? The Social Context Created by Nature in Urban Public Housing. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. Kāhui Tū Kaha to Deliver 24/7 Wrap Around Support Services at 139 Greys Avenue. Available online: https://www.hud.govt.nz/news/kahui-tu-kaha-to-deliver-247-wrap-around-support-services-at-139-greys-avenue (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Horelli, L. The Role of Shared Space for the Building and Maintenance of Community from the Gender Perspective—A Longitudinal Case Study in a Neighbourhood of Helsinki. SocSciDir 2013, 2, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.H.M.S.D.; Rathnayake, R.; Mahanama, P.K.S.; Wickramaarachchi, N. An Investigation on Community Spaces in Condominiums and Their Impact on Social Interactions among Apartment Dwellers Concerning the City of Colombo. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020, 2, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.E.L.; Easthope, H.; Davison, G. Including the Majority: Examining the Local Social Interactions of Renters in Four Case Study Condominiums in Sydney. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 46, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, G.; Leigh, L. Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers; New Zealand Centre for Sustainable Cities: Welington, New Zealand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Sorolla, R.; Montoya, A.K.; Reifman, A.; Carpenter, T.; Lewis, N.A.; Aberson, C.L.; Bostyn, D.H.; Conrique, B.G.; Ng, B.W.; Schoemann, A.M.; et al. Power to Detect What? Considerations for Planning and Evaluating Sample Size. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 28, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvinen, T.; Linnosmaa, I.; Rijken, M. Do people’s health, financial and social resources contribute to subjective wellbeing differently at the age of fifty than later in life? Wellbeing Space Soc. 2024, 7, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.; Wiles, J.; Park, H.-J.; Moeke-Maxwell, T.; Dewes, O.; Black, S.; Williams, L.; Gott, M. Social connectedness: What matters to older people? Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 1126–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, B.L.; Bates, L.; Coleman, T.M.; Kearns, R.; Cram, F. Tenure insecurity, precarious housing and hidden homelessness among older renters in New Zealand. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C.L.; Kwon, C.; Yau, M.; Rios, J.; Austen, A.; Hitzig, S.L. Aging in Place in Social Housing: A Scoping Review of Social Housing for Older Adults. Can. J. Aging 2023, 42, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, S.; Walker, R.; Newhouse, D. Indigenous placemaking and the built environment: Toward transformative urban design. J. Urban Design 2020, 25, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raerino, K.; Macmillan, A.; Field, A.; Hoskins, R. Local-Indigenous Autonomy and Community Streetscape Enhancement: Learnings from Māori and Te Ara Mua—Future Streets Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiddle, R. Engaging Communities in the Design of Homes and Neighbourhoods in Aotearoa New Zealand. CounterFutures 2020, 9, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, L.; Rolfe, S.; Anderson, I.; Seaman, P.; Godwin, J.; Donaldson, C. Intervening in the cycle of poverty, poor housing and poor health: The role of housing providers in enhancing tenants’ mental wellbeing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, K.; Kearns, R.; Opit, S.; Fergusson, E. Facebook as soft infrastructure: Producing and performing community in a mixed tenure housing development. Hous. Stud. 2020, 36, 1769035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslova, S. Delivering human-centred housing: Understanding the role of post-occupancy evaluation and customer feedback in traditional and innovative social housebuilding in England. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. Exploring the Nature of Third Places and Local Social Ties in High-Density Areas: The Case of a Large Mixed-Use Complex. Urban Policy Res. 2018, 36, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Interview: Kaupapa Māori: The Dangers of Domestication. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2012, 47, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

| Data Collection Details | # Of Participants |

|---|---|

| Interviews with CHP representatives | 12 |

| Each interview conducted with a CHP representative involved a semi-structured approach and lasted 1–1.5 h, covering placemaking and community resource provision, rationale, discontinued resources, usage patterns, observed effects, challenges, tenant selection criteria, community engagement, community fostering strategies, Māori and Pacific peoples’ wellbeing considerations, and engagement with cultural values and communities. For the purposes of this study, interview analysis includes all four CHPs who have partnered with researchers on the PH&UR Research Programme. | 4 (TTM) 3 (ŌCHT) 2 (SASH) 2 (DHT) |

| Survey with CHP tenants (‘Your wellbeing at home’) | 113 |

The ‘Your wellbeing at home’ survey consisted of 79 questions covering demographics, life satisfaction and control, dwelling quality and condition, health and wellbeing, sense of belonging, access and travel to/from places, culture and spirituality, affordability, work and education, crime and trust, and household makeup. For the purposes of this study, survey analysis has been limited to participants from the three case study sites around the following:

| 59 Central Park (TTM) 24 Daniell Street (TTM) 30 Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT) |

| Interviews with CHP tenants | 42 |

| Participants for the tenant interview were recruited from the tenant survey, as a subset of the overall survey participant pool. The interview was conversational and lasted anywhere between 30 min and 3 h, covering residency details, accessibility, relocation experiences, impressions of home, complex (where relevant), and neighbourhood, changes over time, community engagement, support networks, amenities, and ideas for improvements. The interview schedule was workshopped with expert colleagues to ensure it would enable exploration of aspects related to Māori and Pacific peoples’ wellbeing [38,39]. For the purposes of this study, interview analysis has been limited to participants from the TTM and ŌCHT case study sites to triangulate and enrich the survey findings. | 18 Central Park (TTM) 10 Daniell Street (TTM) 14 Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT) |

| TTM | ŌCHT | SASH | DHT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHANGE THEORY | Emphasises diverse tenant mixes, strategic community infrastructure, and tenant engagement in placemaking to enhance wellbeing and connections to place and community | Leverages existing neighbourhood amenities, strategic tenancy placement, and tenant support pathways to enhance wellbeing and connections to place and community | Integrates social services, cultural connections, and safe gathering spaces—with the right mix of compatible tenants—to enhance wellbeing and connections to place and community | Prioritises well-connected locations with existing infrastructure that tenants can leverage; views placemaking infrastructure as beneficial, but not essential, to enhancing wellbeing and connections to place and community |

| PLACEMAKING APPROACH | Structured and multi-faceted approach—including both physical infrastructure and social initiatives, including participatory design where possible | Modest, supported approach focused on integrating tenants within surrounding neighbourhood and wider community | Structured approach inseparable from holistic wraparound support and strategic tenancy mixes; about fostering interconnected support networks | Supported approach adaptive to given situation, especially regulatory constraints or site opportunities, in relation to known tenant needs or aspirations |

| COMMUNITY INFRASTRUCTURE PROVISION | Where feasible, on-site provision of community rooms, shared amenities/resources, and green spaces, cultural events, tenant-led activities | Retains existing community rooms, but does not build them in new developments; provides small ‘bump spaces’ and green spaces; leveraging of offerings in wider neighbourhood and community | Corps offices and associated programmes as part of the housing environment, as well as community rooms, shared amenities/resources, and green spaces provided on site where feasible | Multi-functional spaces included on site where opportunity presents; not a core design priority; leveraging of offerings in wider neighbourhood and community |

| Daniell Street (TTM) Combined with Whakahoa Village/ Gowerton Place (ŌCHT) | Central Park Apartments (TTM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 53 | 58 | |

| GENDER | Female | 26 | 17 |

| Male | 26 | 40 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| AGE | 25–54 years | 18 | 17 |

| 55 years+ | 32 | 40 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | |

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS | Employed | 10 | 16 |

| Unemployed | 42 | 40 | |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | |

| ANNUAL HOUSEHOLD INCOME | Less than NZD 20,000 | 21 | 13 |

| NZD 20,000 or more | 27 | 38 | |

| Missing | 5 | 7 | |

| CHILDREN IN HOUSEHOLD? | Yes | 6 | 1 |

| No | 47 | 57 | |

| MEAN YEARS OF RESIDENCE (STANDARD DEVIATION) | 9.04 (8.36) | 9.80 (6.45) | |

| Network_neighbour is a binary variable, so a binary logit model was used for analysis. The other variables are ordinal, so ordinal regression was used. Fully controlled regression estimates, controlling for gender, income, age, employment status, children in household, and length of residency. Note, ease of access to greenspace (ease_green) did not have sufficient variation across the subgroups to calculate standard errors or p-values. S.E. = standard error. | ||||

| Regression Model | Outcome | Estimate | S.E. | p Value |

| UNCONTROLLED | area_suits travel_sat belong_neighbour ease_green safety_hood network_neighbour | 0.159 0.557 −0.114 −0.0428 0.676 0.345 | 0.353 0.349 0.340 0.369 0.358 0.676 | 0.653 0.11 0.737 0.908 0.059 0.61 |

| CONTROLLED FOR GENDER | area_suits travel_sat belong_neighbour ease_green safety_hood network_neighbour | 0.140 0.542 −0.152 −0.0926 0.496 0.268 | 0.363 0.357 0.348 0.376 0.365 0.690 | 0.7 0.129 0.661 0.806 0.174 0.698 |

| CONTROLLED FOR GENDER AND INCOME | area_suits travel_sat belong_neighbour ease_green safety_hood network_neighbour | 0.300 0.559 0.0371 −0.568 0.387 0.204 | 0.385 0.383 0.376 0.413 0.397 0.778 | 0.436 0.144 0.921 0.168 0.329 0.793 |

| FULLY CONTROLLED | area_suits travel_sat belong_neighbour ease_green safety_hood network_neighbour | 0.900 0.747 0.223 - 0.822 0.367 | 0.515 0.513 0.484 - 0.519 1.02 | 0.0807 0.145 0.645 - 0.114 0.718 |

| SITE (CHP) | Change Theory | On-Site Infrastructure | Neighbourhood Access | Safety (Survey) | Belonging/ Connectedness (Survey) | Key Qualitative Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CENTRAL PARK APARTMENTS (TTM) | Structured, participatory placemaking with strategic on-site provision and tenant engagement (exemplified here) | High (community room, kitchen, small library, gym space, laundry, workshop, computer room; garden, courtyard, playground) | High (close to city centre, key amenities, services, and public transport; healthcare access less convenient) | No statistically significant difference vs. comparison sites once controlled (Table 4) | No statistically significant difference vs. comparison sites (Table 4) | Amenities and activities support connection for many; a subset avoids some shared spaces due to safety/harassment concerns |

| DANIELL STREET (TTM) | Same TTM theory; site awaiting upgrades and some distance from aspirational placemaking ideals | Low (basketball court, BBQ, garden, small planted areas) | Medium (convenient location near local centre; hills and lack of cycling infrastructure lower overall access) | No statistically significant difference vs. comparison sites once controlled (Table 4) | No statistically significant difference vs. comparison sites (Table 4) | Tenants draw heavily on nearby New-town facilities; mixed perceptions of safety |

| WHAKAHOA VILLAGE/ GOWERTON PLACE (ŌCHT) | Integration-oriented model; supporting tenants to use existing community infrastructure | Low-mid (some shared amenities and bump spaces; garden) | Medium (close to green space and some essentials; transport more limited) | No statistically significant difference vs. comparison sites once controlled (Table 4) | No statistically significant difference vs. comparison sites (Table 4) | Friendly neighbourly culture and local group participation, alongside some reports of discomfort at night and isolated safety incidents |

| This prototype framework supports public and community housing providers to determine whether, where, and how to invest in community infrastructure and placemaking across the lifecycle of new builds or upgrades. It is grounded in insights from the present case studies and relevant literature, but has not yet been formally tested; it is intended to be adapted and evaluated in different contexts. It recognises that wellbeing outcomes depend not only on the quality of shared physical spaces (like community rooms, gathering areas, or gardens), but also on the presence of social, cultural, and service-based activities that make those spaces meaningful. While grounded in AoNZ’s obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the framework is intended to be adaptable to international settings with comparable legal and ethical commitments to local and Indigenous communities. For those based in AoNZ, the authors recommend that this framework be used in coordination with the recently published Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers [87] and principles underpinning Pacific worldviews [39]. | |||

| Stage | Purpose | Key Questions | Evidence/Tools |

| PARTNERSHIP, CO-DESIGN & ENGAGEMENT (THROUGHOUT) | Build shared ownership, cultural legitimacy, and enduring relationships from the outset |

| MOUs, hui or community meeting notes, co-design and engagement processes, partnership charters, legal obligations, funding requirements, and agreements |

| CONCEPT DESIGN | Develop a shared vision that integrates physical, social, and cultural goals |

| Spatial concepts, early programming ideas, local/cultural reviews, visioning workshops, local authority plans/strategies, community aspirations documents |

| DESIGN DEVELOPMENT | Refine spatial design and programme delivery plans |

| Detailed drawings, cost estimates, service delivery plans, partnership agreements |

| CONSENTING & APPROVALS | Secure required regulatory and cultural approvals |

| Consent applications, cultural and environmental impact assessments, usage outlines |

| CONSTRUCTION & INTEGRATION | Deliver quality spaces and enable early relationship-building |

| Quality inspections, welcome events, tenant onboarding, space commissioning |

| MONITORING & EVALUATION | Track usage, outcomes and feedback over time |

| Post-occupancy evaluation, tenant interviews/surveys, participation data, lessons learned, maintenance plans |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olin, C.V.; Witten, K.; Randal, E.; Chisholm, E.; Logan, A.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Leigh, L. Placemaking and the Complexities of Measuring Impact in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Public and Community Housing: From Theory to Practice and Lived Experience. Architecture 2025, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030069

Olin CV, Witten K, Randal E, Chisholm E, Logan A, Howden-Chapman P, Leigh L. Placemaking and the Complexities of Measuring Impact in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Public and Community Housing: From Theory to Practice and Lived Experience. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030069

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlin, Crystal Victoria, Karen Witten, Edward Randal, Elinor Chisholm, Amber Logan, Philippa Howden-Chapman, and Lori Leigh. 2025. "Placemaking and the Complexities of Measuring Impact in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Public and Community Housing: From Theory to Practice and Lived Experience" Architecture 5, no. 3: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030069

APA StyleOlin, C. V., Witten, K., Randal, E., Chisholm, E., Logan, A., Howden-Chapman, P., & Leigh, L. (2025). Placemaking and the Complexities of Measuring Impact in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Public and Community Housing: From Theory to Practice and Lived Experience. Architecture, 5(3), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030069