1. Introduction

Aotearoa New Zealand (AoNZ) continues to face challenges in delivering housing that is both suitable and supportive of diverse needs, particularly for vulnerable populations such as those diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), also known as autistic people. The interplay of rising housing costs, increasing demand for public and community housing, and an urban housing stock that too frequently overlooks the diverse needs of its residents—such as the needs of autistic people—has created a pressing issue in AoNZ [

1,

2,

3]. Although affordability remains a key focus of housing policy, the inclusivity and adaptability of these dwellings can be marginalised in planning and design decisions [

4,

5]. Furthermore, ASD is often infantilised, with autistic people commonly imagined as children—overlooking the reality that autistic children grow into adults who may seek independent or semi-independent living [

6]. Such infantilisation contributes to a lack of appropriate support and housing options available to autistic adults, particularly when their parents or wider family are no longer able to house and care for them. In AoNZ, support systems are limited, with families often needing to navigate complex processes to access funding [

7]. Those with less obvious support needs

1 are especially likely to be overlooked. As such, this exploratory study focuses on autistic adults with less severe needs or those who have previously been diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome.

The importance of home as a place of security and identity is well-documented, with research highlighting its role in shaping wellbeing, autonomy, and social integration [

1,

5]. Yet for individuals with ASD, standard housing designs can lead to sensory and spatial challenges that undermine their ability to live independently [

8,

9,

10]. The built environment plays a fundamental role in shaping experiences for autistic individuals, yet public and community housing projects—which could offer substantial contributions in this space [

11,

12]—usually fail to consider autism-friendly design as a priority. Those in AoNZ who do recognise the importance of autism-friendly housing lack the required funding to undertake such projects [

13]. Internationally, research has explored the relationship between housing design and ASD, but much of this work has focused on privately owned residential settings, such as cluster housing developments, rather than public and community housing—also known as social housing [

9,

14].

In AoNZ and for the purposes of this study, public and community housing refers to dwellings managed by either Kāinga Ora—Homes and Communities, a government-owned entity, or registered Community Housing Providers (CHPs). These homes are allocated to individuals and families listed on the public housing register, which is maintained by the Ministry of Social Development (MSD). Eligibility for this housing is determined based on several factors, including residency status, income and asset thresholds, and the severity of housing need. The register prioritises those who cannot access or sustain tenancies in the private rental market due to these criteria.

The architectural and spatial design of public and community housing—and associated public housing design guides [

4]—in AoNZ remains largely oriented toward general physical accessibility features without explicit consideration of cognitive and sensory accessibility features such as the needs of autistic individuals [

15]. Public and community housing designs vary in how well they support autistic individuals. For example, Te Kī a Alasdair in Wellington [

16] provides high-density community housing with some accessibility features but limited sensory considerations. The symmetrical layout and simple circulation paths create a familiar and easy-to-navigate environment for autistic tenants, but the lack of communal areas may contribute to social isolation. Te Mātāwai in Auckland [

17,

18] provides support services within a mixed-tenure model, but its design does not appear to explicitly address the sensory sensitivities of autistic residents. While the use of colour-coded doors for wayfinding and ground-floor communal spaces fosters social connections, the open-plan kitchen and living spaces may pose sensory challenges for some tenants due to the lack of clear thresholds. Similarly, Central Park Apartments—another high-density community housing site in Wellington [

19]—incorporates community amenities but lacks modifications to accommodate the needs of autistic residents. The redevelopment of this site

2 introduced colour-coded building sections, a community room, and improved passive surveillance, enhancing safety. However, the open-plan kitchen and living spaces blur programmatic boundaries, which may create discomfort for some autistic residents. These examples highlight a gap in design strategies that explicitly support autistic individuals within AoNZ’s public and community housing sector. Architecturally, the main shortcomings of these developments—which may hinder autistic adults—include open-plan layouts that can be confusing for autistic adults, limited apartment size, colour and material choices that risk overstimulation or poor indoor health, and lighting conditions that create uncomfortable environments.

International case studies offer some insights into design strategies tailored to autistic individuals. Linden Farm in the UK [

20] demonstrates the impact of sensory-friendly supported housing tailored for autistic individuals. The design prioritises sensory regulation, with gradual lighting transitions, high ceilings, and restrained material and colour palettes inside the dwelling. However, the stark contrast between interior and exterior finishes risks overstimulation for colour-sensitive residents. The Sweetwater Spectrum Community in the USA [

21,

22] provides a purpose-built housing model for autistic adults with adaptable, sensory-conscious spatial configurations. The development incorporates a hierarchy of spatial organisation, clear transition thresholds, and reduced sensory stimuli through subdued colours and indirect lighting, contributing to a calm and predictable environment for residents. De Hogeweyk in the Netherlands [

23,

24], while primarily a dementia-focused community, illustrates the benefits of placemaking and environmental familiarity. Research has highlighted parallels between dementia and autism, particularly in relation to sensory sensitivities, spatial orientation challenges, and the need for structured environments [

25,

26]. As such, De Hogeweyk’s design approach—emphasising clear wayfinding, predictable environments, and controlled sensory stimuli—offers some insights that may be valuable for autism-supportive housing models. Architecturally, international case studies that support autistic adults emphasise sensory environments in housing design, creating more comfortable spaces for autistic adults. Simple colour palettes and indirect lighting reduce visual stimuli, while natural materials lower exposure to harmful chemicals.

Table 1 summarises architectural features that support or hinder autistic adults, based on the case studies considered in this study, which include public and community housing in AoNZ and international examples designed for autistic adults or those with similar needs.

In response to growing recognition of comprehensive design guidance for accessibility needs in public and community housing [

4,

5,

27,

28,

29], this study takes an explorative approach to ask how housing design might facilitate and help enable semi-independent living for autistic adults with less obvious support needs. By integrating existing knowledge on autism-friendly environments with insights from participatory research and a speculative redesign exploration, this paper proposes guiding principles and detailed guidance points for public and community housing design that align with the unique and too-often-overlooked needs of this population.

The following sections present the study’s methodology, key findings from participatory research, and the development of a speculative redesign of a community housing site in Newtown, Wellington, AoNZ. The paper concludes with a discussion of the study’s implications, including a critical reflection on feasibility and limitations, and presents a set of guiding principles—with detailed guidance points—to support housing providers, architects, and other stakeholders in creating more inclusive living environments for autistic adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Partnership, Multimethodological, and Iterative Approach

This exploratory study has been undertaken as part of the Public Housing and Urban Regeneration: Maximising Wellbeing (PH&UR) Research Programme

3 [

30], and in partnership with Wellington’s largest Community Housing Provider (CHP), Te Toi Mahana (TTM)

4 [

31]. A key component of this partnership has been sustained engagement with TTM, as well as industry and other stakeholder organisations to ensure the research remains both grounded in real-world housing challenges and is useful and relevant for the industry. This engagement has taken multiple forms, including initial site selection discussions with TTM in early 2024, collaboration on identifying potential tenant participants, and ongoing dialogue regarding research findings. Regular touchpoints, including participation in research presentations and follow-up meetings, have facilitated an exchange of knowledge and ensured that emerging insights can contribute to TTM’s work, including their future housing upgrades and redevelopments. Furthermore, key TTM staff were involved in project reviews, providing critical feedback on the speculative design explorations.

Beyond TTM, the research has engaged with other professionals working in the public and community housing sector, including Novak + Middleton Architects, who provided expert critique of the in-progress research and design explorations, then evaluated the final body of work by giving verbal feedback during an in-person presentation of the findings, and written feedback following. Their long-standing expertise in designing public and community housing has provided a valuable industry perspective, supporting the refinement of the study’s guiding principles. From reviewing the concept design, feedback from Novak + Middleton Architects helped shape the refinement of the apartment design through critical feedback regarding the optimisation of apartment footprints. This clarified funding requirements for public and community housing in AoNZ, and helped ensure the final design proposal would be viable within these requirements. Further discussions took place with Community Housing Aotearoa (CHA) and the Autism Charitable Trust, a recently registered CHP focused on housing autistic adults. These engagements helped situate the study within a broader conversation on the right to housing, the availability of appropriate housing options for autistic adults, and the intersections between design, industry, and policy.

Alongside partnership, a multimethod and iterative approach was used (see

Figure 1), recognising that no single method can fully address the complexities of autism-friendly housing design for semi-independent living. The process was non-linear, with methods building on and informing one another to enrich the research from multiple angles. Literature and case study analysis established a theoretical foundation and international precedents, participatory methods brought in user-driven insights, and early design explorations tested emerging ideas spatially. Together, these informed the development of the guiding principles and detailed guidance points, which sat at the centre of the process and were continually refined as the study progressed. As shown in

Figure 1, the methods were interrelated and overlapping rather than sequential, with the guiding principles and guidance points both shaped by and feeding into each phase. The speculative redesign of an existing TTM community housing site in Newtown, Wellington, tested these principles through tangible—though ambitious—design solutions. This approach enabled a holistic investigation that bridged research, design, and industry needs—ensuring the findings are grounded, relevant, and responsive to the current gap in autism-friendly housing strategies.

2.2. Participatory Methods and Analytical Approach

The participatory phase of this research—approved by the Victoria University of Wellington Human Ethics Committee (ID: 0000031565)—was central to understanding the lived housing experiences, preferences, and needs of autistic adults. Following ethics approval, written informed consent was obtained from each participant. They were also welcome to have a support person present during their participation. This exploratory study employed a participant-led photo elicitation method followed by semi-structured interviews. While this approach shares methodological roots with the photovoice method developed by Wang and Burris [

32], it was adapted to suit the study’s interpretive and design-oriented focus. Participants were invited to document their homes and neighbourhoods by photographing spaces they found comfortable, overwhelming, socially enabling, or restrictive, as these themes were highlighted as important by the literature and case studies [

8,

9,

10,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. These images then formed the basis for one-on-one interviews, rather than group discussions, as used in traditional photovoice. This adaptation aligns with previous research highlighting photo-based methods as effective in engaging neurodivergent individuals [

33] and helped accommodate participants’ communication preferences. It also mitigated the risk of discomfort or withdrawal in group settings, ensuring each participant’s perspective was clearly heard. The use of imagery helped bridge cognitive and verbal communication barriers, offering direct insight into participants’ spatial and sensory experiences.

Out of respect for privacy and to mitigate any ethical concerns, all potential participants were first contacted by key TTM staff and through Autism New Zealand social media posts. Interested parties then contacted the researchers directly to be involved in the study. Many expressions of interest were received after multiple triangulated recruitment efforts were made through TTM and Autism New Zealand; however, only three autistic adults (with less obvious support needs) decided to participate from TTM and Autism New Zealand. While the small sample size was not intentional, it reflects the difficulty of engaging this often-overlooked group within housing research and highlights the need for further participatory studies. It also presents a methodological limitation in terms of the diversity and representativeness of perspectives captured. Nevertheless, the qualitative depth of data offers meaningful insights into housing design considerations for this population, with several key similarities evident across participant accounts. Following the photo elicitation phase, semi-structured conversational interviews were conducted, focusing on participants’ preferences for spatial organisation, experiences of sensory stimuli—such as lighting, sound, and materials—interactions with shared spaces, and adaptations to their environments.

Thematic analysis [

34] was undertaken to make sense of the collected data and to identify patterns and commonalities across participants’ responses. This involved an iterative coding process, beginning with listening to interview recordings and transcribing the discussions. Key points were then reviewed and assigned provisional themes related to spatial comfort, stress triggers, privacy preferences and social engagement. These preliminary codes were refined and collated into a shared list, which guided the analysis of each individual participant’s input. Participant photographs were also reviewed and annotated, with sketches used to highlight recurring spatial preferences and design needs. These were then synthesised into overarching themes, focusing on key design moves relevant to autism-friendly housing. Data was coded manually and cross-checked against the existing literature to ensure consistency and alignment with broader research findings. Findings from the participatory phase were used to refine the study’s guiding principles and related guidance points, as reported in the results section of this paper, and informed the speculative redesign exploration.

2.3. Speculative Redesign of Community Housing Site

The speculative redesign phase served as a means to test, develop, and further refine the guiding principles and guidance points derived from the literature, case study analysis, and participatory research. Focusing on one of TTM’s community housing sites that is currently awaiting upgrades (see

Figure 2), this iterative design approach allowed for the practical application of identified principles in a real-world housing context. This focus ensured the study’s applicability to current challenges and constraints of public and community housing provision in AoNZ.

The speculative design process employed a research-through-design methodology, incorporating iterative design development cycles. The process was structured into three primary stages: (1) analysis of the existing site and its relationship with the surrounding urban fabric which identified existing strengths—such as the presence of some shared outdoor spaces—and weaknesses—including the lack of clear transitions between public and private spaces and limited opportunities for sensory retreat; (2) preliminary design explorations—beginning with individual apartment design—that provided a structured means of evaluating design proposals against core principles such as safety, choice, predictability, and sensory modulation—and in turn evaluated the effectiveness of the guiding principles and guidance points; and (3) refinement of the design proposal based on stakeholder engagement and feedback.

Furthermore, iterative refinement of the speculative design proposal was informed by ongoing discussions with stakeholders, including TTM and industry experts, ensuring that the proposal remained both feasible and aligned with the needs of autistic adults. Initial design explorations were tested and enhanced through spatial modelling, sketching, and feedback sessions. The resulting design proposal and key design considerations are discussed alongside other results in the next section of this paper.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Lived Experiences of Home

Data collected through participatory methods outlined in the previous section—a photo elicitation study followed by semi-structured interviews—captured participant views on spaces that shape their daily routines, comforts, and interactions with others, providing nuanced perspectives on how they navigate and adapt their home environments. This section presents results from this data, highlighting common themes and spatial considerations that emerged from participant accounts.

The three participants who agreed to take photos of their current homes were provided with a series of 10 photo prompts (

Table 2), and given two weeks to take their photos, which resulted in 76 photos (see

Figure 3) being taken between them.

Table 2 lists the full set of photo prompts and accompanying descriptions as well as some examples of participant photos in response to each prompt. These prompts were developed through thematic analysis of the literature and case studies, identifying key aspects of the home environment that are particularly important for autistic adults. They were written in plain language to ensure accessibility for participants. To ensure anonymity, raw image files were password-protected and accessible only to the primary researcher. Pseudonyms were used in all reporting, and identifying details—such as family photographs and street names—were blurred from the images.

Despite the small participant pool, there were a number of key similarities between participants’ accounts of their lived experiences, desires, and concerns, with four overlapping themes common: (1) viewpoints, (2) visual privacy, (3) spaces to connect, and (4) connection to the outdoors. These results are discussed in more detail in the following paragraphs.

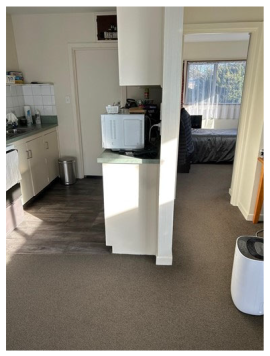

Two of the strongest themes to emerge from participant responses were viewpoints and visual privacy. All participants expressed (through photographs and follow-up interviews) the desire to look out of their windows to connect to the wider urban environment but to do so in ways where they felt visually safe and secure.

“I’ve always been more comfortable in spaces that are up higher when I can see out. […] Looking at nice things [out the window] makes it easier to make me happy like that. That’s what it is with autism, I get sensitive to things, so the things I like I really really like, and the things I don’t like I really really don’t like”.

All participants expressed feeling uncomfortable and unsafe when they knew others could see into their homes and observe them (e.g., if windows were placed too low, lacked appropriate screening, or faced shared walkways). “I like being able to look out and occasionally looking out at the street, but I don’t like people being able to look in and see me… so that’s why we have the blinds” [

36]. “I like having the net curtains because they provide a bit more privacy” [

37]. To improve their visual privacy, all participants used some form of curtain or blind to reduce exposure to the public eye while at home (see

Figure 4). These findings highlight the importance of ensuring that dwelling designs balance outward connectivity and personal security, particularly for autistic adults, who may be more sensitive to feeling observed in their private space. Further studies indicate that feeling safe at home is not just about physical security but also about visibility and interactions with the surrounding environment [

38,

39,

40].

“[…] curated boundaries, limitations, lines of flight, “blind spots”, and spaces of total visibility—all within which architecture itself exerts both ostensible and surreptitious power over the lives of human beings”.

Careful window placement, screening options, and the ability to regulate sightlines are critical design considerations for autistic adults who may have heightened sensitivities to personal boundaries. Ensuring adjustable privacy solutions, such as operable louvres, layered window treatments, or controlled sightlines through careful site layout and urban design, can enhance both visual security and access to outdoor views.

From participant responses, it became apparent that housing design solutions for autistic adults need to take the surrounding environment into account. Easy access to spaces outside of the dwelling to connect—with friends, with family, and/or with the wider community—were important to the autistic adults who participated in this study. The lack of these spaces readily available to them in their current home environments posed challenges, with one participant (who lives alone) describing feelings of loneliness and isolation due to the lack of accessible and inviting spaces for social connection (see

Figure 5): “this place is very alienating because there’s nothing here [for me]” [

35].

This finding also aligns with existing research on public housing environments, which highlights the critical role of well-designed public and shared spaces in fostering social ties and mitigating isolation. Studies have shown that accessible community spaces—such as courtyards, community rooms, and well-maintained green spaces—are particularly valuable for tenants who may have limited space within their homes and limited mobility to access such spaces further afield [

41]. For autistic adults, these shared spaces may be even more crucial, not only for facilitating social interaction but also for providing structured and predictable environments where they can engage with others on their own terms.

Furthermore, the desire to connect to the outdoors through viewpoints and outdoor spaces was highlighted by two of the three participants in this study (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), as illustrated by the following interview quotes and photographs:

“I like sitting out [on the deck] if it’s nice weather, I can always see people going past”.

“[Having bush/outdoor zones on site] would be nice, I love having trees around… that’s what I liked when I lived back in Poland… they built big buildings but they were relatively far apart with trees and grass in-between and I liked that… it was a shock when I moved here and saw that there wasn’t really that and it was more carparks in-between”.

Easily accessible green spaces can offer autistic adults safe, restorative environments that support mental wellbeing, enable self-regulation for those who find nature calming, and allow for the creation of diverse sensory experiences [

14,

42,

43]. Access to outdoor spaces can support autonomy and sensory regulation by providing opportunities for self-directed engagement with the outdoor environment in spaces that cater to their preferences [

43]. However, the extent to which outdoor spaces are beneficial depends on their quality and accessibility. Poor maintenance, lack of seating, and safety concerns can deter use, as seen in public housing developments where tenants avoid outdoor areas due to crime or neglect [

41]. To ensure that outdoor spaces effectively support both autistic adults and others, they should be designed with a variety of spatial conditions—combining open areas for movement and social interaction with quieter, sheltered nooks for retreat. Providing seating, shade and natural elements can enhance comfort and usability, while ensuring ongoing maintenance and security can help foster a sense of safety.

These findings captured through participant photography and follow-up interviews highlight key spatial and sensory considerations that influence the ability of autistic adults to feel safe, comfortable, connected and independent in their home environments. While each participant had unique experiences and perspectives, common themes emerged around the importance of viewpoints, visual privacy, spaces to connect with others, and connection to the outdoors. These insights reinforce the need for housing, site and neighbourhood design that challenges assumptions and takes into account the nuanced needs of autistic adults, who offer insights to improve public and community housing that may benefit a wider tenant population as well. The next section of this paper presents guiding principles for autism-friendly housing design, developed through a critical review of the literature and case studies, then refined based on participant insights and speculative design explorations.

3.2. Guiding Principles and Related Guidance Points for Autism-Friendly Housing Design

Design guidance provides a structured approach to translating research into practical design considerations. Rather than prescribing fixed solutions, guidance offers flexible recommendations that can be adapted across different models and contexts [

8,

43]. For this study, the researchers have taken a principled approach to guidance, which is intended to assist housing providers, architects, urban designers, and other professionals and stakeholders in creating more inclusive and supportive living environments for autistic adults. The guidance presented as a result of this exploratory study has been developed iteratively by critically engaging with the relevant literature, case studies, participant photos and follow-up interviews, and design investigations.

While the guiding principles and guidance points presented here (

Table 3) are presented as results to be utilised and further tested in the design of future public and community housing environments, their development was also crucial as part of the research process: they helped guide, test, and refine the speculative redesign of an existing community housing site. In turn, the design explorations helped to further refine the guiding principles, which were approached from multiple directions to form an integrated body of work. Developed through a critical review of the academic literature reporting on research undertaken in AoNZ and internationally, through the analysis of case studies also spanning AoNZ and international contexts, and participatory studies, seven key principles were identified to structure the guidance: (1) familiarity and clarity, (2) health and safety, (3) choice, (4) public–private interface, (5) sensory environment, (6) external environment, and (7) privacy.

The first principle, familiarity and clarity, explores how clear layouts and predictable spaces can enhance comfort and support wayfinding within the home. The second principle, health and safety, highlights the importance of accessible design features and safe housing developments in ensuring tenant wellbeing. The third principle, choice, emphasises the need to provide options throughout the built environment, allowing tenants to tailor spaces to their individual needs and maintain control over their living situation. The fourth principle, public–private interface, focuses on balancing communal and private spaces within housing developments, as well as ensuring clear boundaries and transitions between public and private areas to reduce anxiety and enhance both security and autonomy. The fifth principle, sensory environment, addresses how design can respond to visual and auditory sensitivities, creating comfortable spaces that minimise overstimulation. The sixth principle, external environment, extends accessible design considerations beyond the dwelling, recognising the role of well-designed outdoor and shared spaces in fostering connections with nature and the wider community while maintaining a sense of safety and comfort. Finally, the seventh principle, privacy, highlights the importance of carefully designed private spaces that give tenants control over their personal environment, supporting a sense of security and providing areas for self-regulation when needed. These spaces also help establish clear boundaries for those living in shared housing.

3.3. ‘Apartment Seed’ Method: Speculative Designing with Principles from the Inside Out

Utilising the guiding principles and guidance points, the speculative design method involved an iterative process that alternated between refining the individual dwelling(s) and the wider development. Alternating between the two scales allowed for greater refinement of the design, ensuring a strong relationship between the individual dwelling and surrounding built form and spaces, aiding wayfinding through the development and wider urban environment [

44,

45,

46]. This meant that design explorations started with the individual apartment—termed an ‘apartment seed’

5 in this study, as the wider development formed and grew out of it—or standardised designs that were replicated and adapted throughout the housing development (see

Figure 8). This exploratory method of designing was chosen as a way of prioritising tenants and their immediate home environments, echoing recent findings from the PH&UR Research Programme about the priority housing providers give individual dwellings before other amenities—such as shared or community spaces [

47], ensuring the immediate living condition for autistic adults was considered first and foremost. Furthermore, this method allowed for autistic people’s dwelling needs to be heard and used as key design drivers from the ‘inside out’, enabling autism-supportive design decisions about immediate home environments to be made early on in the process. This method focused on the lived experiences of the immediate home environment earlier than the more common ‘outside in’ approach would, allowing autism-supportive dwelling design decisions to have a much greater impact on the wider buildings and site masterplan [

46].

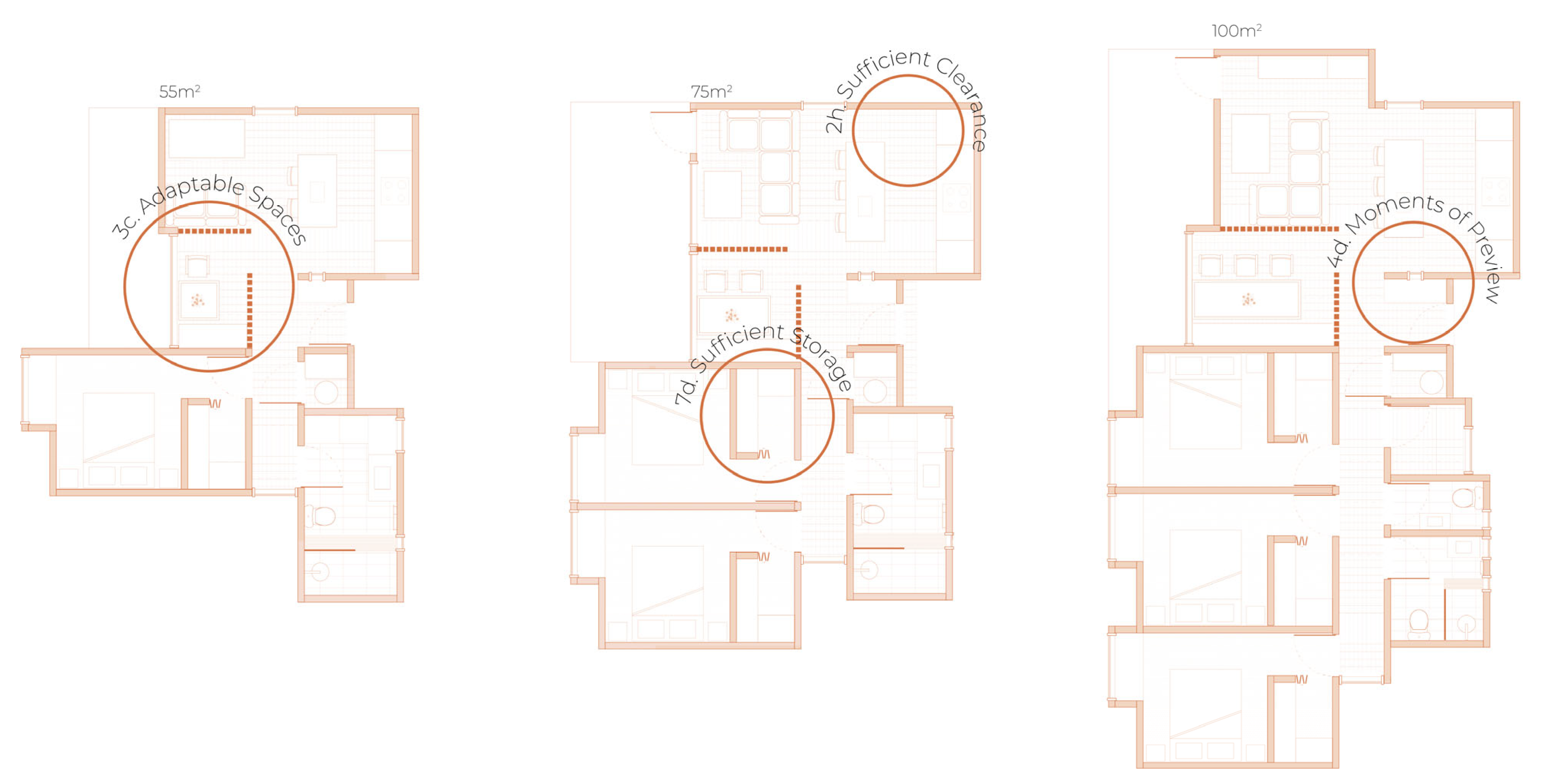

Given that autism is a spectrum, the type of support needed for each individual can vary immensely. While some autistic adults prefer to spend time alone, others may enjoy socialising and spending time in shared spaces or feel more supported knowing there are others at home. Providing different types of dwellings acknowledges that autistic adults have preferences just like anyone else in the wider population, and that they have the right to be able to choose what dwelling type they reside in, as highlighted in existing research [

48,

49,

50]. This has been echoed in specialty developments overseas, with Linden Farm in the UK offering one-, two-, and three-bedroom facilities across their developments [

51]. In response, this proposal includes one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments in the design that cater to autistic people’s needs (Guidance Point #3a). Tenants would have the option to live individually or with others, while larger apartments could accommodate families with autistic members more comfortably. Although apartment sizes vary, all follow a consistent layout, with spatial dimensions adjusted according to intended occupancy. Apartment sizes align with public and community housing guidelines in AoNZ [

4], which specify maximum size thresholds for funding eligibility. In this study, the designs stayed within those limits: 55 m

2 for one-bedroom apartments

, 75 m

2 for two-bedroom apartments, and 100 m

2 for three-bedroom apartments (

Figure 9).

Shared spaces such as the kitchen, living, and dining areas are located at one end of the apartment, while private spaces such as bedrooms and bathrooms are located at the other (Guidance Points #1b; 4f; 4g; 6f), establishing clear boundaries between public and private spaces and forming a clearly defined public–private gradient

6 (Guidance Point #1b). Timber slatted walls were found to be an effective solution to creating clear thresholds, offering spatial separation while allowing light and views to pass through, and providing moments of preview and retreat throughout the dwelling (Guidance Points #4d; 4e). This approach supports sensory awareness and clarity of spatial boundaries while maintaining a sense of openness that resonates with the familiarity and clarity and public–private interface guiding principles.

Dropped ceilings were introduced to further reinforce clarity of navigating the public–private gradient and help support the sensory environment. Ceilings in shared spaces are raised significantly higher than those in private spaces to shift spatial atmosphere and reinforce the programmatic intention of each zone. Recessed LED strips are integrated into the dropped ceilings throughout each dwelling to support a more sensory-friendly living environment by avoiding harsh downlights, diffusing light to produce a softer ambience that reduces sensory stimuli and gives occupants control over lighting intensities and hues (Guidance Point #5d). The strips are placed around the perimeter of each ceiling, ensuring gentle, even lighting throughout the room (see

Figure 10).

Alongside lighting, a restrained colour palette and natural materials reduces sensory stimuli and creates a calmer environment to support comfortable and healthy environments (Guidance Points #2i; 5a; 5b). Echoing participant concerns, windows are positioned carefully to ensure privacy, and sills throughout the dwellings are raised higher than typical to prioritise user comfort (Guidance Points #6a; 6b). In bedrooms, these raised window sills allow for built-in seating and storage (

Figure 11), providing different spaces for users to sit within their private space (Guidance Points #6c; 6d).

Alongside the sensory environment, ensuring the dwellings meet suggested health and safety guidelines is crucial. The main area of concern in this regard is the kitchen, due to its inherent dangers with the use of cooking appliances. Recognising the importance of safe kitchen design, clearance around benchtops and appliances was increased to help reduce potential injury (Guidance Points #2g; 2h), also allowing multiple people to cook safely at once in shared dwellings (see

Figure 12). The oven is raised above ground to help reduce risks associated with bending down to reach inside.

3.4. Wider Development—Speculative Re-Design of TTM Housing Site

While the ‘apartment seed’ design focuses on the internal layout and sensory experience of individual dwellings, the full speculative redesign of TTM’s community housing site includes an expanded scope to consider how the wider development could support autistic tenants’ wellbeing, autonomy, and social connectedness. This includes a mixed-tenure approach to housing, the inclusion of a versatile community hub with on-site support, and a variety of shared outdoor spaces on both the ground floor and rooftops. Together, these design strategies aim to reduce isolation, offer appropriate support, and foster a stronger sense of community among all residents.

Initial research into cluster housing models—where multiple units for people with disabilities are grouped together—suggests limited benefits for quality of life [

52,

53]. Dispersed housing—which integrates specialised dwellings amongst mainstream ones—is considered more inclusive [

53]. To adapt this model to the scale of TTM’s 0.6-hectare site, a medium-density mixed-tenure approach was adopted. Mixed-tenure models can reduce stigma and improve community outcomes [

54,

55]. In this proposal, most autism-friendly units are distributed across the site, with a small cluster included for those who prefer proximity to others with similar needs (Guidance Point #3b). In line with Kāinga Ora’s

7 accessibility policy [

4], at least 15% of all units are designed to be accessible for autistic tenants.

While participants expressed a desire for community connection, they also faced barriers such as limited facilities, accessibility challenges, and social anxiety. When social activities are regular, predictable, and embedded in everyday settings, they are more likely to feel manageable and meaningful for autistic adults [

56]. Accordingly, a multi-functional community hub near the site’s edge is proposed to provide inclusive social infrastructure accessible on site (Guidance Point #4a). Some of the guidance points have been utilised in the design of the community hub to ensure it is comfortable and effective at providing a space for people to come together. For example, its location on site was chosen to ensure clear thresholds between the public-facing community hub and private residential spaces. This hub is designed to include set spaces for staff and for socialising, along with flexible spaces for events and activities. Drawing on Shea [

57], a small café and shop are proposed within the hub with the hope that they may provide comfortable everyday settings in which autistic tenants can spend time and engage with others outside of their dwellings. Similarly to the apartments, this café features a dropped ceiling to improve the acoustic environment, diffuse lighting, and create a more comforting atmosphere within a larger flexible space (Guidance Point #5d). Furthermore, the community hub was designed utilising the public–private interface principle as a key driver (Guidance Point #4f). The ground floor space is public, with semi-public and private spaces located on the first and second floors, respectively. A restrained colour and natural material palette are again utilised to reduce sensory stimuli and reduce potential toxicity from the use of unnatural building materials (Guidance Points #5a; 5b; 2i). To improve user comfort—and as participants suggested is important—window sills are again raised higher than typical to reduce the fear of being seen (Guidance Point #6a).

To further support those who require assistance with daily living, space is provided for an on-site carer. Some autistic tenants may live independently, while others may benefit from support with day-to-day tasks and executive functions, such as nourishing themselves and maintaining good hygiene. Inspired by the case studies Linden Farm and Sweetwater Spectrum Community, the proposed development includes dedicated space for an on-site carer who would be available 24/7 to help when required. This space is situated in-between tenants’ more private residential spaces and the public-facing community hub (Guidance Points #2c; 2d), to help maintain boundaries between public and private, and to mitigate any intrusion of tenants’ privacy. This positioning allows the carer to be close to both tenants in the residential area, and to other staff working in the community hub, while maintaining clear boundaries and privacy.

A variety of shared outdoor facilities are included within the wider development proposal to enhance wellbeing and support the formation of connections throughout the community (Guidance Point #4a). At ground level, facilities are open to the public, with tenants given priority access. This aims to build connections between tenants and the wider community in safe and familiar spaces. Shared garden spaces throughout the site provide quiet spaces for reflection and nature connection, while a community garden encourages participation—for those who wish—in shaping the space and connecting with others over collaborative gardening activities. This participation benefits those who have a special interest in gardening or want to learn more about it [

43]. Taking inspiration from the site’s existing offerings, a basketball court is provided to support physical activity in a flexible setting (see

Figure 13), with seating provided around the edges for those who prefer to observe rather than participate.

To make better use of rooftop areas and offer more outdoor amenities, each building in the proposed development includes additional shared facilities above. These are reserved for tenants only, providing quiet refuge from the more public ground-floor spaces. Rooftop amenities include silent gardens (see

Figure 14), butterfly gardens, green roofscapes, play areas and shared barbeque areas. This range of environments supports different sensory and social preferences, giving tenants more autonomy over how and where they spend their time (Guidance Points #3d; 4a; 7b; 7d).

The results of this exploratory study highlight a set of recurring spatial and design preferences expressed by the literature, case studies, and autistic participants, including the need for visual privacy, outward viewpoints, access to outdoor space, and clearly defined social environments. While individual experiences varied, there was notable alignment across participant accounts, reinforcing the relevance of these priorities for future housing design. The guiding principles and related guidance points developed in response were tested and refined through the speculative redesign of one of TTM’s community housing sites, offering a grounded application of participant insights and exploration of how design can respond to these insights in an urban context. Together, these findings provide a practical starting point for considering how public and community housing in AoNZ—and, potentially, elsewhere—might better support autistic adults to live with greater comfort, autonomy, and security. The following discussion situates these findings within the broader literature, reflects on their implications for housing, site and neighbourhood design, and outlines key limitations and suggestions for future research.

5. Conclusions

The current housing market in AoNZ puts autistic adults at a disadvantage due to its inaccessibility, even within the public and community housing sector. This inaccessibility may have detrimental impacts on autistic adults who currently rely on support from their parents, wider family and friends, when these support networks can no longer help care for them. This exploratory study aims to aid architects, urban designers, housing providers, and other professionals and stakeholders in the design and development of autism-friendly housing that helps support and enable semi-independent living for autistic adults, which can help ease the anxiety of those individuals and their supporters looking ahead to an uncertain future. While applicable to many dwelling types and context, this study has focused on the design of medium-density public and community housing in an urban setting in AoNZ.

Honed from the literature review, case study analysis, and participatory research, this study has developed seven guiding principles to consider when designing autism-friendly living environments: (1) familiarity and clarity, (2) health and safety, (3) choice, (4) public–private interface, (5) sensory environment, (6) external environment, and (7) privacy. These principles are accompanied by detailed guidance points (as listed in

Table 3). The development and testing of these principles and their guidance points through a speculative design process was an effective method of developing and illustrating the spatial and architectural qualities needed to help enable semi-independent living for autistic adults in future public and community housing. In doing so, this study offers a foundational step toward better supporting the autism community and those who advocate with and for them.