Abstract

This paper explores the complexities of measuring impact from placemaking in the context of public and community housing (sometimes known as social or subsidised housing) in Aotearoa New Zealand. Placemaking refers to a range of practices and interventions—including the provision or facilitation of access to community infrastructure—that seek to cultivate a positive sense of place through everyday experiences, spaces, relationships, and rituals. Drawing on interviews with four community housing providers (CHPs), analysis of their documentation, and tenant survey and interview data from two of those CHPs, this research examines providers’ change theories about placemaking in relation to tenants’ experiences of safety, belonging and connectedness, including access to local amenities, ease of getting around, and a sense of neighbourhood and community affiliation. Based on the importance of these variables to wellbeing outcomes, the study highlights the potential of placemaking to support tenant wellbeing, while also recognising that providers must navigate trade-offs and co-benefits, limited resources, and varying levels of tenant engagement. While placemaking can help to foster feelings of connection, belonging and safety, its impact depends on providers’ capacity to initiate and sustain such efforts amidst competing demands and constraints. The study offers indicative findings and recommendations for future research. Although the impacts of placemaking and community infrastructure provision are difficult to quantify, research findings are synthesised into a prototype framework to support housing providers in their decision-making and housing development processes. The framework, which should be adapted and evaluated in situ, potentially also informs other actors in the built environment—including architects, landscape architects, urban designers, planners, developers and government agencies. In Aotearoa New Zealand, where housing provision occurs within a colonial context, government agencies have obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi to actively protect Māori rights and to work in partnership with Māori in housing policy and delivery. This underscores the importance of placemaking practices and interventions that are culturally and contextually responsive.

1. Introduction

1.1. Placemaking in Public and Community Housing

Public and community housing plays a crucial role in providing affordable and secure homes for vulnerable populations [1]. A recent systematic literature review by Chisholm et al. [2] highlights how crucial it is to understand the dynamics of placemaking in public and community housing contexts, and reveals some key gaps in our current knowledge. Placemaking can be understood as “practices through which people form a sense of place, and interventions to encourage a sense of place” [2,3]. While placemaking initiatives in these contexts generally promise to boost tenants’ wellbeing and belonging, Chisholm et al.’s [2] review reveals that we are not seeing the full picture across different housing communities worldwide. For example, there is not enough research on how changes in the physical layout of neighbourhoods affect people’s feelings about their community. We are also missing insights into how placemaking efforts unfold over time, which is important for developing effective strategies to support tenants’ long-term wellbeing and belonging in a place. While public and community housing tenants generally feel a strong connection to their communities, there is not much research on how different groups within these communities experience placemaking [2].

One key factor affecting tenants’ sense of place in public and community housing is how long they have lived there and how secure they feel in their housing [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Changes in housing policies or redevelopment projects can disrupt this sense of connection and lead to tenants feeling excluded, marginalised, or uncertain about their future in a place [10,11,12]. This all underscores the need for more research to dive deeper into placemaking processes and outcomes that can help foster safety, belonging, and connectedness in the context of public and community housing, and to derive evidence-based strategies that genuinely work for tenants and for their housing providers. In response to this need, the authors—researchers within the Public Housing & Urban Regeneration: Maximising Wellbeing (PH&UR) Research Programme1—have investigated how public and community housing providers in Aotearoa New Zealand (AoNZ) think about placemaking and its capacity for positively impacting the lives of their tenants. This includes strategies for delivering or facilitating access to community infrastructure, encompassing both physical elements (e.g., community rooms, gathering spaces) and social and operational components (e.g., events, wrap-around services, and cultural considerations). Placemaking often involves creating or activating this infrastructure to foster people/people and people/place connections. The study examines the role of placemaking and community infrastructure in tenants’ experiences of safety, belonging, and connectedness. In doing so, it explores relationships between tenants’ experiences and the underlying change theories that inform each provider’s placemaking efforts.

Change theories “represent theoretical and empirically grounded knowledge about how change occurs” [13]. In relation to placemaking and community infrastructure provision, policies advocated by each housing provider likely stem from certain ideals or beliefs (the theoretical) and understandings about what kind of initiatives have worked or not worked in the past (the empirical) about how change occurs. These change theories “go beyond one project” and are held across an organisation, ideally providing the underlying rationale of each project, or the theory of change “which supports planning, implementation, and assessment” [13]. By illuminating a provider’s change theory about the anticipated impact of placemaking efforts on tenant wellbeing, then examining how that theory relates to the design/development of, and service provision at, specific housing sites and tenants’ experiences of living at those sites, we can gain insights into how impactful design, activation, and engagement strategies may be for tenants’ sense of safety, belonging, and connectedness, both in their immediate housing areas and in their broader neighbourhoods and social networks.

1.2. Aotearoa New Zealand Housing Context

AoNZ—like many countries around the world—is grappling with significant challenges in creating accessible places of belonging for its population, particularly in the face of urgent housing demands, rising living costs, and pressures associated with urbanisation [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Arguably, the most important place of belonging is one’s home [20,21,22], yet too many people do not have access to this human right [19,23]. As recently articulated by Paul Gilberd, CEO of Community Housing Aotearoa (CHA), the peak body for AoNZ’s community housing sector:

“New Zealand’s housing history has had its highs and lows. There were times when the majority had adequate housing, strong communities, and affordable living costs, with housing taking up about a third of household income. But New Zealand and the world have changed significantly in recent decades. More families are finding it harder to live securely and affordably. Supporting them is a key challenge, which community housing organisations have taken up”.[24]

In AoNZ, public and community housing refers to affordable rental homes provided either by the central government housing agency Kāinga Ora—Homes and Communities, or by community housing organisations. Registered community housing providers (CHPs)—including charitable trusts, iwi (Māori tribes), hapū (Māori sub-tribes), Pacific, and faith-based groups—are eligible to receive the government Income-Related Rent Subsidy (IRRS) to house people on the Public Housing Register. The IRRS covers the difference between tenants’ rent (usually set at 25% of their income) and market rent. In addition to registered CHPs, other community housing organisations may offer alternative affordable housing options—including rentals and assisted ownership—but are not eligible for the IRRS. Together, these organisations provide a diverse and growing sector aimed at ensuring all people are well housed [25]. There is currently more demand for this housing than there is supply [19,26,27]. Yet while the quantity of dwellings provided is important, how those dwellings are designed and developed in coordination with their surrounding context, and through processes inclusive of communities and stakeholders, is equally important. “Access to high quality affordable housing helps to foster community development, reduces social inequality, and promotes social inclusion” [19].

As noted by Rangiwhetu et al. [28], “[h]ousing for low-income populations… differs in form depending on the context and country”; in AoNZ, there is a noticeable variety in the form and arrangement of public and community housing, from stand-alone single-family houses to medium-density townhouses and apartment blocks that incorporate community infrastructure and, to a lesser degree, high-density and mixed-use/mixed-tenure developments [29,30,31]. Sites vary in both size, from small dwelling plots to housing developments covering entire city blocks, and in some cases, large regeneration areas, and location, from centrally located urban sites to more isolated suburban and rural areas [32]. Certain housing forms, arrangements, sizes, and locations are better suited to meeting tenants’ needs and fostering a sense of safety, belonging, and connectedness, while others present more challenges in achieving these outcomes [2,33,34]. In other words, public and community housing have varying levels of success when it comes to placemaking.

Placemaking is understood by CHA to be “crucial in rebuilding social connectedness and cohesion” [24]. In the first edition of their recently initiated Impact Report, CHA declared the following:

“Community housing providers believe in community building, which means creating mixed, diverse, and inclusive developments and delivering homes, not just houses… The most successful community-led developments deliberately include shared spaces, community hubs, and ‘bump spaces’ (a public space to promote community connection), to support residents in getting to know each other in mixed-tenure environments”.[24]

Public and community housing tenants in AoNZ represent diverse groups with varied experiences, needs, and aspirations. Around 39% identify as Māori [14,27,35], many of whom (mana whenua) have intergenerational connections and rights to a place, while others (mātāwaka) may live away from their ancestral whenua (land). Eligibility criteria for the Public Housing Register have become increasingly targeted to people with severe and persistent needs, including homelessness, disability, and poor health [36]. As a result, housing providers are working with complex tenant demographics—from isolated older adults to single parents and large whānau—each with different needs for connection, support, and cultural recognition. This diversity underscores the importance of placemaking strategies that are flexible, culturally and contextually responsive, and capable of supporting a range of everyday lives and relationships.

1.3. Structure of the Paper

In what follows, the study’s materials and methods are described, including its focused scope within the broader PH&UR Research Programme. While the programme includes both large-scale public housing regeneration areas and CHP development sites, this study focuses solely on the latter. The authors employed a mixed-methods approach—described further in the following section—to test the following hypothesis: In CHP developments where comprehensive community infrastructure is provided on site, a higher proportion of tenants will report their neighbourhood meets their needs, including their access to green space; report a greater sense of safety and belonging in their neighbourhood; and report a greater sense of belonging to social networks in their community than tenants living in developments where such infrastructure is limited or absent on site. The authors recognise the limitations of these methods, particularly with respect to the tenant participant sample, and treat the findings as indicative rather than definitive.

The results are presented in two parts. First, the change theories of four CHPs are introduced and used to interpret levels of access to on-site and neighbourhood community infrastructure and green space across five case study sites, as evaluated through site visits, spatial analysis, and accessibility index scores. Second, tenants’ experiences are examined by comparing survey responses from three of those sites in relation to two of the CHPs’ change theories. Tenant interviews are used to triangulate and enrich the survey findings. The discussion reflects on these findings in light of the relevant literature and working hypothesis. The paper concludes with indicative findings, recommendations for future research, and a framework to support housing providers in their decision-making and processes around placemaking and community infrastructure provision. The framework is positioned as an empirically grounded synthesis of the case study analyses and relevant literature rather than a tested model; it is offered as a prototype to guide practice and to be adapted and evaluated across contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Partnership and Multimethodological Approach

This study forms part of the PH&UR Research Programme, undertaken in partnership with six public and community housing providers On behalf of the wider programme, dedicated research liaisons negotiated partnerships with four CHPs—Dwell Housing Trust (DHT); Salvation Army Social Housing (SASH); Ōtautahi Community Housing Trust (ŌCHT); and Te Toi Mahana (TTM), which transitioned from Wellington City Council (WCC) City Housing to became a registered CHP during the research period—and two large-scale public housing regeneration programmes—Tāmaki Regeneration Company (TRC); and Eastern Porirua Development (EPD), which Kāinga Ora: Homes and Communities (KO) are undertaking in partnership with the local council and mana whenua. The researchers understand that measuring the impact of provider placemaking efforts on tenant experiences is complex and cannot be captured by a single study or method. While this study does not claim to provide definitive answers to the aforementioned hypothesis, it seeks to generate insights through the use of multiple methods across a focused set of CHPs and case study sites. Data collection, which took place between 2022 and 2024, included semi-structured interviews with CHP staff, document analysis, site visits, spatial analysis and scoring of an accessibility index2, a tenant survey called ‘Your wellbeing at home’, and conversational interviews with a sub-sample of tenant participants. The authors were granted approval by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (21/115, D22/205, and D22/190) to conduct this study.

Interviewees from the four CHPs—TTM, ŌCHT, SASH, and DHT—were organisational representatives selected for their roles in developing or managing dwellings, community infrastructure, and tenancies, and for their knowledge or involvement in placemaking efforts (see Table 1 for a detailed summary of data collection involving participants). To inform and contextualise these interviews, the research team also analysed publicly available documents from each CHP, including policies, strategies, development plans, design guidance, and communications material3.

Table 1.

Data collection methods involving participants.

From the four CHPs whose representatives were interviewed and whose documentation was analysed, the study hones in on two—TTM and ŌCHT—and three case study sites. Two of these sites—Central Park Apartments and Daniell Street (Wellington) —are owned by Wellington City Council and managed by TTM. The third site—Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (Christchurch)—is owned by Christchurch City Council and managed by ŌCHT.

All case study sites in the broader PH&UR Research Programme were initially identified in collaboration with partner providers, based on their potential to demonstrate diverse placemaking conditions, contribute to other programme research aims, and allow for appropriate tenant recruitment and participation. Some, such as TTM’s Central Park Apartments or SASH’s Kaitiakitanga housing, represented recently upgraded or new developments with a high level of on-site community infrastructure. Others, such as Daniell Street, were older developments awaiting upgrades and offered a useful contrast. In each case, site selection reflected a partnership approach and was shaped by providers’ knowledge of their portfolios and tenants.

For the purposes of this study, site selection was further refined based on a combination of practical and analytical considerations. First, the study required sites where tenant survey responses were sufficiently concentrated to allow meaningful analysis. This excluded developments provided by DHT, where respondents were geographically dispersed, and supported the exclusion of large regeneration areas, where low response numbers at one site limited the potential for meaningful comparison with the other. Second, the study prioritised sites that could be grouped into two broad categories: those with high levels of on-site community infrastructure and good local access (Central Park Apartments) and those with lower levels of on-site provision but similarly good access to surrounding community infrastructure (Daniell Street and Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place). Controlling for good neighbourhood access in both groups allowed the analysis to isolate the added value—if any—of on-site provision for tenants’ reported safety, belonging, and connectedness. A potential fourth site, provided by SASH, did not align clearly with either group because its neighbourhood offered more limited community infrastructure.

Members of the research team visited each site to inform the spatial analysis, photograph key features (while respecting tenant privacy), and contextualise other data. The spatial analysis drew on architectural drawings from TTM and ŌCHT, GIS data, the Wellington and Christchurch District Plans, and other relevant urban planning and historical sources. Data from an accessibility index provided information on how easily tenants can reach essential services and amenities by driving. The index is an aggregate measure of proximity to a range of community infrastructure, such as public transportation, green space, and facilities like grocery stores, healthcare centres, and schools, and the area’s overall access rank.

Tenant participants were first recruited to participate in a survey (Figure 1) distributed to their households during June–August 2022; a sub-sample of these tenant participants agreed to participate in further research and, from these, 42 were recruited from TTM and ŌCHT to be interviewed about their experiences of home, place, and belonging in their housing development and surrounding neighbourhood4.

Figure 1.

Survey with CHP tenants (photo by first author).

2.2. Analytical Approach

In this multimethodological study, the researchers employed a range of analytical techniques to bring the data together and generate meaningful results. For qualitative data gathered from interviews with CHP representatives and organisational documentation, the researchers used thematic analysis—a flexible method for developing patterns of meaning through a process of deep engagement and interpretive analysis [39]. This approach facilitated a nuanced exploration of how CHPs understand and enact placemaking and community infrastructure provision, particularly in relation to tenant outcomes. Codes were developed inductively through repeated, reflective engagement with the data, and then organised into themes that captured shared meanings. Rather than seeking consensus or reliability across coders, the researchers foregrounded analytic depth, theoretical coherence, and transparency in interpretation, in keeping with the principles of reflexive thematic analysis [37,40].

For analysis of the three case study sites that are the focus of this paper, a triangulated approach was used, combining site visits, interview data, spatial analysis, and accessibility index scoring. The spatial analysis drew on data from multiple sources to document site- and neighbourhood-level features relevant to wellbeing outcomes. It was used to assess each site’s layout, the presence and distribution of community infrastructure and green space, and the relationship between each site and its surrounding neighbourhood, including access to a broader network of community infrastructure and green space. An accessibility score was estimated for all Statistical Area 1 (SA1) areas in AoNZ and extracted for each site. Locations of education, employment, transport, health, recreation, retail, social and cultural facilities, Māori cultural sites, and environmental ‘bads’—such as gambling and alcohol outlets—were collected from publicly available sources (central and local government databases, GeoHealth Labs, Overture, and Open Street Maps) and a commercial data provider (National Map), and used to rank the access from each SA1 centre to each service category using an enhanced 2-step floating catchment method [41,42]. SA1s were then assigned quintiles based on these ranks for each service category and an overall mean rank. Together, these analyses provide a comprehensive view of each CHP case study site’s physical environment, including any on-site community infrastructure—community rooms, gathering spaces, green spaces, community gardens, play areas, etc.—provided for tenants, in relation to the physical environment and community infrastructure accessible to tenants in the surrounding neighbourhood.

‘Your wellbeing at home’ survey data were analysed to identify associations between CHPs’ approaches to placemaking and their tenants’ reported experiences of safety, belonging, and connectedness. For the analysis presented in this paper, respondents were placed into one of two location groups based on where they lived. Group one represented people who lived in a site with high on-site service provision and good local amenities (Central Park Apartments), and group two represented those who lived in areas with lower on-site services and fewer, although still relatively good, local amenities (Daniell Street and Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place). After data cleaning and summary socioeconomic and demographic descriptions of the groups were carried out, regression analyses were used to identify associations between differences in respondents’ scores on six outcome measures and their location group. The outcome measures, detailed in Table 1, were whether the area suits the respondent’s needs (area_suits), ease of access to green space (ease_green), feelings of safety when walking alone after dark in the neighbourhood (safety_hood) (measured on a 5-point Likert scale), travel satisfaction (travel_sat) and a sense of belonging to the neighbourhood (belong_neighbour) (measured on a 10-point scale), and a binary variable indicating membership to a neighbourhood group (network_neighbour). Ordinal regression was used for the 5- and 10-point scale variables, and a binary logit model was used for the binary variable. Ordinal regression was chosen for the scale variables because it is designed for data that represent ordered responses with unquantifiable and potentially unequal intervals between points [43]. Four regressions were carried out for each outcome variable. Firstly, an uncontrolled regression using only the dummy location group as the explanatory variable; secondly, controlling for gender; thirdly, controlling for gender and income; and finally, a full model controlling for gender, income, age, employment status, number of children in the household, and length of residency. All analyses were carried out in R (version 4.4.2) using the Ordinal package [44].

For qualitative data collected from interviews conducted with a sub-sample of the survey respondents (CHP tenants), the researchers’ analysis was supplementary and involved a close reading of transcripts to identify quotes that spoke to key themes emerging from the survey data. For the purposes of this study, these interviews were not analysed as a standalone dataset, nor were they coded thematically in the same way as the CHP interviews. Rather, selected quotes are used in this paper to illustrate key points, enrich the interpretation of the survey findings, and offer additional context from the tenant perspective5.

Together, these methods enable the interrogation of multiple, diverse datasets to provide an understanding of how placemaking and community infrastructure strategies are shaped and implemented by CHPs, and how they relate to tenants’ lived experiences. Findings are presented in the following section, beginning with each CHP’s change theory and its spatial and infrastructural manifestations across the case study sites.

3. Results

3.1. CHPs’ Change Theories About Placemaking and Community Infrastructure

The four CHPs whose representatives were interviewed for this study each hold distinct but overlapping change theories about the role of placemaking and community infrastructure in relation to tenant outcomes. While their approaches differ, all recognise that physical and social environments shape tenants’ experiences of safety, belonging, and connectedness. The researchers’ understanding of placemaking—as the “practices through which people form a sense of place, and interventions to encourage a sense of place” [2,3]—aligns with these theories, though its application and manifestations vary.

TTM’s change theory emphasises diverse tenant mixes, strategic community infrastructure provision, and tenant engagement in design and placemaking as key to fostering social connectedness and community interactions. Their approach sees placemaking as structured and multi-faceted, integrating both physical infrastructure (e.g., community rooms, shared spaces) and social initiatives (e.g., cultural events, tenant-led activities). This has been realised most comprehensively at their Central Park Apartments site in Wellington:

“For Central, it was very much a placemaking exercise, so we had a lot of community engagement, placemaking experts, literature, and we had… IAP2 (The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) is a global organisation dedicated to promoting and enhancing public participation in decision-making processes. Established in 1990, IAP2 serves individuals, governments, institutions, and other entities that affect the public interest. Its mission is to advance public participation through education, advocacy, and the development of best practices.) [training]… which was really successful. We wanted the tenants to feel like they were an integral part of making their homes—that was probably the top priority. And they were involved in every stage of the design. We did make changes every time based on that”.[45]

While challenges exist in resourcing for infrastructure provision and maintaining sustained tenant engagement, TTM understands placemaking as a long-term strategy for tenant wellbeing and community resilience, rather than as a one-off intervention. When placemaking opportunities are missed or awaiting the right resourcing, this is recognised, such as with their housing along Daniell Street, which is described as “a family site” that “doesn’t have a lot” in terms of community infrastructure and is “quite concrete-y for the kids”, which is “a shame” [46].

ŌCHT, on the other hand, places a greater emphasis on integrating tenants into the broader community, on placemaking that is supported by the surrounding context. As one representative explained:

“Our model is that we don’t include community services. Our model is that we work with our tenants so they reach out into what is around them. What we do, it’s a little bit of the navigation. We will know of all the services that are available to them, be it doctors, dentists, all the usual, parks, schools, and we will advise people”.[47]

Their change theory posits that leveraging existing neighbourhood services and amenities, alongside strategic tenancy placement and diversified household types, enhances tenant wellbeing, social connectedness, and sense of place. ŌCHT retains community rooms on older sites, but instead of providing extensive infrastructure in new developments, it prioritises locating these developments near existing services and amenities and supports tenants to access those resources. Within their new developments, placemaking efforts focus on modest interventions, such as “bump spaces… gardens, all those kinds of things” [47], which facilitate passive social interaction and may help strengthen community ties. ŌCHT also supports tenants through limited social support roles, including digital skills and employment mentoring. While not delivering employment services directly, staff help tenants connect with job opportunities and external networks, aligning with their broader goal of fostering independence and community integration.

For SASH—a faith-based organisation—placemaking is structured and inseparable from holistic wraparound support services and strategic tenancy mixes. Nearly every SASH housing site has “a corresponding [Salvation Army] corps office nearby” [48], forming part of the suite of community infrastructure they provide or support access to, to facilitate social, cultural, and spiritual wellbeing. Where possible, SASH also provides substantial on-site community infrastructure, such as community rooms, kitchens, and gardens. This extensive provision is enabled by their unique positioning within the wider Salvation Army network:

“The structure… is so much to get your head around because there’s the church side and then there’s the army side, and then you’ve got the chaplaincy which is a different part of that as well. So, this is another really awesome thing about Salvation Army is just the resources we can pull from… We’ve got like chaplaincy and stuff like that and these corps offices, [which are] in that area to support not only our tenants but just the local congregation and stuff like that as well. Run programmes, do English classes and just be there in general to support”.[48]

Their change theory posits that integrating social services, cultural connections, and safe gathering spaces into housing developments—with the right mix of compatible tenants—strengthens tenant wellbeing and community. For SASH, placemaking is largely about fostering interconnected support networks.

DHT takes a pragmatic, opportunity-driven approach to placemaking, viewing the provision of on-site community infrastructure—particularly physical spaces such as community rooms and shared spaces—as beneficial but not essential. Their change theory prioritises well-connected locations with existing community infrastructure, which can support tenants to connect with people and place:

“We choose our locations carefully so that people aren’t at a loss when we build out because they can walk to a park. They can walk to the library. They can walk to the school yard. And hear the water, you know, the ocean, so I guess the point would be we take every location very seriously and weigh up that series of factors”.[49]

When community spaces are incorporated into DHT developments, they are multi-functional and shaped by external requirements or opportunities, rather than forming a core design priority. The organisation’s placemaking to date has not been systematically planned, but rather has emerged responsively—shaped by regulatory constraints, site opportunities, and known tenant needs or aspirations. This adaptive approach is evident in DHT’s Kilbirnie development, Mahora Te Aroha, where district planning regulations required a commercial frontage along Onepu Road. Rather than resisting the requirement, DHT embraced the opportunity to house their offices and a space shared with tenants: “We could have fought that, we actually could have fought that but we thought, no, this is good” [49]. A similar scenario unfolded with an unused 33-square-metre piece of land with unclear ownership next to their site. Although DHT were not able to build on this piece of land without a lengthy and expensive process, they were advised that they could “just have it there”; not wanting to turn their back on the opportunity, they envision using it as a shared amenity for their tenants: “a green space for all twenty-nine homes” [49].

Across these four organisations, change theories reveal both commonalities and key differences in how CHPs seem to conceptualise placemaking and community infrastructure in AoNZ (Figure 2). While all acknowledge the importance of connections to people and place for supporting tenant wellbeing, their strategies range from more structured placemaking where feasible (TTM, SASH) to supported approaches that focus on leveraging existing infrastructure and opportunities (ŌCHT, DHT). These perspectives shape not only how CHPs develop housing, but also how they engage with tenants and the broader community, influencing the potential impact of placemaking efforts. Table 2 summarises the four CHPs’ change theories, placemaking approaches, and community infrastructure provision.

Figure 2.

Authors’ interpretation of the conceptual approaches to placemaking and community infrastructure among four CHPs in AoNZ (diagram by first author). NOTE: This diagram represents the authors’ interpretation of data collected and analysed for this study; it does not necessarily reflect official CHP policies, and the CHPs depicted may describe their placemaking approaches differently.

Table 2.

Change theories, placemaking, and community infrastructure across four CHPs.

In what follows, three case study sites across two of these CHPs—TTM and ŌCHT—are presented, with the results of researchers’ spatial analysis and accessibility index scoring together illustrating how these sites manifest (or not) their providers’ change theories about placemaking and community infrastructure provision. Notably, both TTM and ŌCHT have origins in council housing. TTM’s transition from Wellington City Council’s social housing portfolio is relatively recent (2023), while ŌCHT was established by Christchurch City Council in 2016 to manage its social housing units. Despite this shared background, they have developed distinct conceptual approaches to placemaking and community infrastructure, reflecting their unique change theories.

3.2. CHP Case Study Sites

The three case study sites—Central Park Apartments (TTM), Daniell Street (TTM), and Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT)—demonstrate how two CHPs’ change theories about placemaking and community infrastructure provision manifest in practice and in relation to each site’s wider neighbourhood.

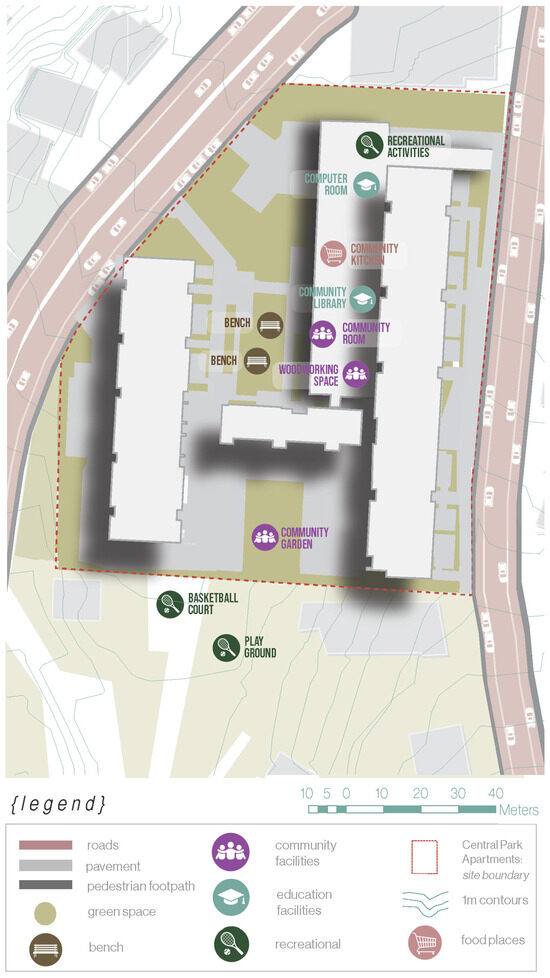

Central Park Apartments (Figure 3 and Figure 4) represents TTM’s most comprehensive example of structured placemaking and integrated community infrastructure. This site—upgraded in 2012 through a design process informed by IAP2 tenant engagement—aligns closely with TTM’s change theory, which emphasises connectivity with people and place through diverse tenant mixes, strategic community infrastructure provision, tenant engagement, and placemaking as a long-term strategy. The development features an unusually high level of on-site community infrastructure, including a large community room, community kitchen, small library, flexible gym space, laundry, woodworking workshop, and computer room (Figure 4). These physical on-site provisions are complemented by a range of on-site services, activities, and events offered, overall reducing reliance on external community infrastructure. Further, this comprehensive on-site provision serves not only tenants of Central Park Apartments, but also acts as a kind of hub for tenants from further afield. The site’s green space provision is also strong, with a community garden, a playground, landscaped courtyards, mature trees, and adjacency to Wellington’s Central Park. The accessibility index scoring for Central Park Apartments is high due to its proximity to key amenities, services, and bus transport routes (Figure 3). The site is within walking distance of the city centre, public transport, and educational institutions. However, healthcare access is less convenient, requiring, in most cases, additional transportation. Overall, Central Park Apartments exemplifies TTM’s structured approach to placemaking, where tenant engagement and diversity combine with comprehensive on-site community infrastructure provisions to support tenant wellbeing.

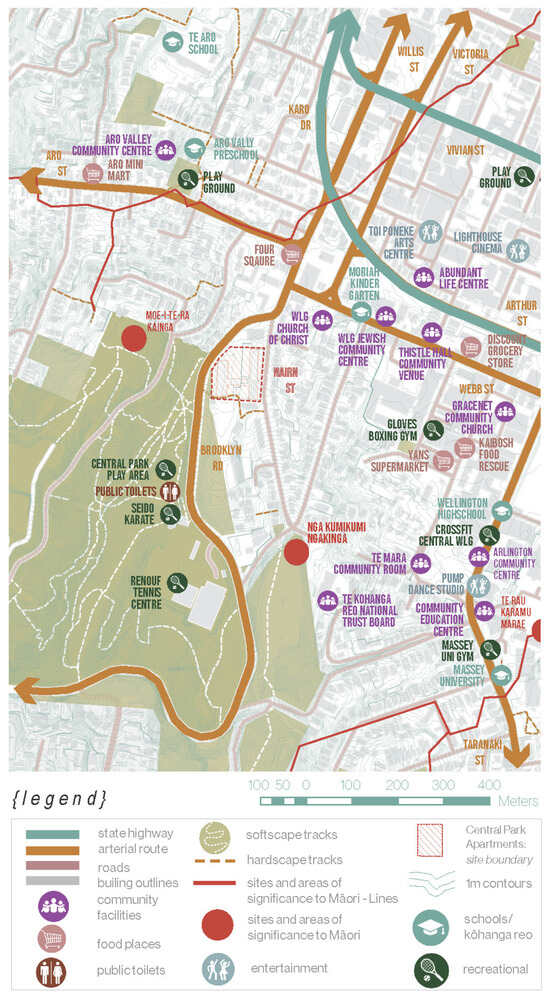

Figure 3.

Access to neighbourhood community infrastructure from Central Park Apartments (TTM); high accessibility index score (drawing by Lucy Kokich).

Figure 4.

High level of on-site community infrastructure at Central Park Apartments (TTM) (drawing by Lucy Kokich).

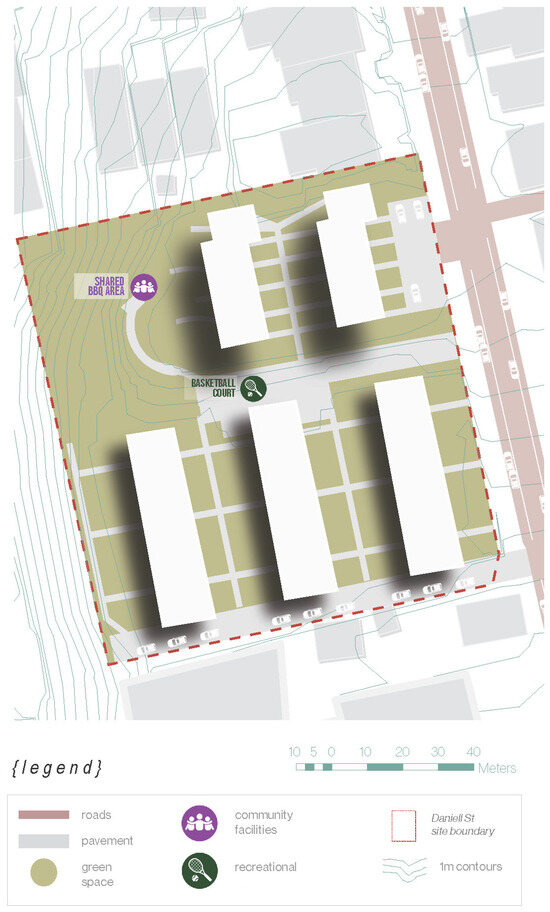

In contrast to Central Park Apartments, Daniell Street housing (Figure 5 and Figure 6), which consists of a collection of buildings and sites pepper-potted along the street, reflects TTM’s recognition of placemaking gaps. On-site community infrastructure within the Daniell Street housing consists of a basketball court, BBQ area, one community garden, and small planted areas (Figure 6). The back corner of one site is covered in native bush. This case study illustrates TTM’s acknowledgement that some of their housing—particularly that due for upgrades, including housing along Daniell Street—is some distance from their aspirational placemaking ideals. This site lacks quality shared and community spaces. Minimal physical community infrastructure also limits the potential to offer substantial services, activities, or events on site. Tenants instead draw on the surrounding neighbourhood for services, including parks, other TTM housing sites, and Newtown’s centre, which includes a library, community centre, low-cost doctor, supermarket, and other shops (Figure 5). The accessibility index scoring for Daniell Street is medium, reflecting its convenient location within Newtown, but also some barriers to access. While the site is well-connected by bus routes and walkable, the hilly topography and lack of dedicated cycling infrastructure reduce overall accessibility. Daniell Street serves as a counterpoint to Central Park Apartments, demonstrating that TTM’s approach to placemaking and community infrastructure provision is not uniformly applied across its housing portfolio. While Central Park Apartments reflects TTM’s aspirations for high-quality community housing, Daniell Street highlights areas for future intervention.

Figure 5.

Access to neighbourhood community infrastructure from Daniell Street (TTM); medium accessibility index score (drawing by Lucy Kokich).

Figure 6.

Low level of on-site community infrastructure at the largest Daniell Street housing site (TTM) (drawing by Lucy Kokich).

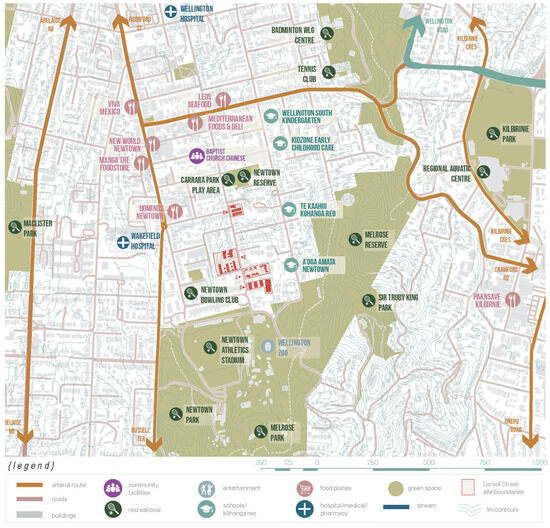

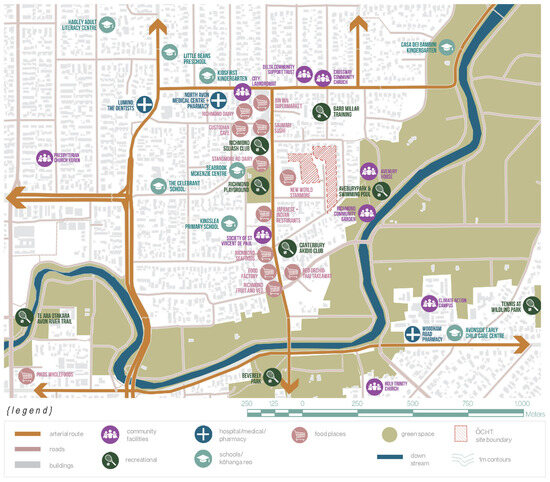

Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (Figure 7 and Figure 8) illustrate ŌCHT’s approach to placemaking as primarily about community integration rather than extensive on-site provision. These sites feature some limited community infrastructure, far less than Central Park Apartments, aligning with ŌCHT’s change theory that tenants should be integrated into the surrounding neighbourhood rather than relying on in-house services. Shared amenities on site include a community garden at Gowerton Place and seating that supports social interaction in good weather (Figure 8). The wider neighbourhood offers Richmond Community Garden, Avon Park, Avebury House, and a local supermarket (Figure 7). The accessibility index scoring for Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place is medium due to mixed levels of connectivity. While it is close to green space and some essential services, transport access is limited. Unlike TTM—which actively invests in placemaking as a structured strategy—ŌCHT focuses more on placing developments in well-connected locations and encouraging tenants to engage with existing community infrastructure. Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place reflects this philosophy, manifested in a site with low-mid on-site placemaking situated within wider community offerings.

Figure 7.

Access to neighbourhood community infrastructure from Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT); medium accessibility index score (drawing by Lucy Kokich).

Figure 8.

Low-mid level of on-site community infrastructure at Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT) (drawing by Lucy Kokich).

These three case study sites illustrate the practical manifestations of TTM and ŌCHT’s differing change theories and approaches to placemaking, as well as the possibilities and limitations presented by their sites. TTM invests in structured, tenant-led placemaking and substantial on-site provision of community infrastructure where possible (e.g., Central Park Apartments), but not all of their housing stock reflects this aspirational level of investment (e.g., Daniell Street). ŌCHT takes a more external-facing approach, placing less emphasis on on-site community infrastructure and more emphasis on supporting tenants to integrate within their wider community and neighbourhood. Both CHPs provide housing in locations with reasonable (medium-to-high) accessibility to a range of services and amenities, but Central Park Apartments stands out as the site with the most amenities, with a greater potential to reduce tenant reliance on external infrastructure. Together, these case studies illustrate some of the trade-offs and co-benefits between structured placemaking and integration-based approaches taken by providers, setting the stage for further discussion on how these different approaches may impact tenant experiences of safety, belonging, and connectedness.

3.3. Insights from Tenant Survey Responses

Tenant survey responses were grouped into two study groups across the three case study sites; see Table 3 for the socioeconomic and demographic description of these study groups.

Table 3.

Socioeconomic and demographic description of the study groups.

Survey responses indicate generally positive perceptions of neighbourhood suitability and satisfaction with ease of getting around. However, responses on belonging, group participation, and safety at night are more mixed, with minimal differences between Central Park Apartments (TTM) and the grouped responses from Daniell Street (TTM) and Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT) (please see Supplementary Materials provided for an illustration of these results).

Table 4 presents regression results of the survey analysis, which are the estimated contribution to changes in the outcome variable for living in Central Park Apartments (with a high level of on-site community infrastructure) compared to living in Daniell Street or Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (with a low- or low-mid level of on-site community infrastructure). Positive estimates can be interpreted as an improvement in the outcome variable by living in Central Park Apartments rather than in Daniell Street or Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place. Negative estimates indicate a worsening in the outcome variable for those in Central Park Apartments versus Daniell Street or Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place. No results were significant at the p < 0.05 level, meaning that the 95% confidence interval for all results includes “0” (i.e., no difference between Central Park Apartments and Daniell Street or Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place). Initial (uncontrolled) analysis of the survey data suggested that tenants living at Central Park Apartments might have had a greater sense of safety when travelling around their neighbourhoods after dark (safety_hood). However, once gender differences between Central Park Apartments and Daniell Street or Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place were controlled for, these differences disappeared. Controlling for other socioeconomic and demographic differences (Table 3) between the two groups did not find any significant associations between location group and any of the outcome variables.

Table 4.

Regression estimates for being in Central Park Apartments (TTM) vs. Daniell Street (TTM) combined with Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place (ŌCHT).

In sum, the survey results point to broadly similar experiences of safety, belonging, and connectedness across Central Park Apartments, Daniell Street, and Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place. Despite different levels of on-site community infrastructure, survey results show minimal differences between developments, and interview data from a subset of survey respondents point to a diversity of tenant experiences at each site, as discussed in relation to each theme below.

3.4. Tenant Experiences of Safety

The survey’s safety_hood item revealed moderate feelings of safety overall and no statistically significant difference between Central Park Apartments and the comparison group of Daniell Street with Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place, once gender was controlled for. Interviews confirm this mixed picture. Several interviewees from Central Park Apartment reported feeling safe, with some expressing their appreciation for upgraded access controls: “You need a code to get into the building… extra safety is very good” [50]. Yet several still described living on alert, with vigilance extending beyond the front door. One Central Park Apartment tenant described having “some pretty scary experiences coming home late at night” [51], and another admitted to weighing up each short errand:

“Moving about the place… I always think, should I take my cell phone with me because you’re never sure when you’re going to encounter anyone who’s disorderly or drunk or having a domestic dispute”.[52]

At Daniell Street, a ground-floor tenant relayed neighbourly warnings when they first moved in, not to hang clothes out “because [they] will get stolen”, and worried that glass-panel doors “would be easy to get in”. They concluded that they “don’t really feel that safe here” [53]. Yet another interviewee from Daniell Street described feeling “very safe”, although “there was that one night… someone was trying to get through the back door” [54]. Another reported “the odd occasion where I’ve seen like say sketchy looking characters… but apart from that, no, I don’t think there’s too many places where I don’t sort of walk” [55].

At Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place, an interviewee reporting feeling “mostly” safe and “pretty secure”, despite incidents such as a recent “fight and someone was out with a machete” [56]. One tenant reported simply, “I feel safe, yes, no problem” [57], while someone answered directly, “No, I don’t” [58] in response to the question “Would you say you feel safe where you are?”. Another interviewee from Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place reported feeling safe in their building and “in the daytime in my neighbourhood”, but that the neighbourhood “feels a bit worrisome and heavy on you somehow” and said they “wouldn’t necessarily feel safe in the evening” [59].

These accounts point to layered and sometimes contradictory experiences of safety being shaped by many things, including—but not limited to—personal histories, gender, site design and building details, mental health, and unpredictable dynamics.

3.5. Tenant Experiences of Belonging and Connectedness

Belonging and connectedness are interrelated and encompass both people/place ties (neighbourhood suitability, travel satisfaction, ease of reaching green space) and people/people ties (social networks and community). Survey items on belonging to the neighbourhood (belong_neighbour) and to local groups showed mid-range scores with no site differences. Survey indicators (area_suits, travel_sat, ease_green, network_neighbour) were generally positive but again showed no significant site effect. The subset of survey respondents who were interviewed often discussed belonging and connectedness together.

Interviewees from Central Park Apartments offered diverse perspectives on what supports—or sometimes limits—their sense of belonging and connectedness. One tenant described how a nearby community art studio helped foster a critical sense of place-based stability: “If [art studio] wasn’t here, I would probably unravel because it would mean that I would be more isolated” [52]. Another tenant volunteers with a group located beyond the complex: “I’m the administrator of a community group… outside Central Park” [60]. Another relies on friendships across the city for whom they rely on for help and companionship, explaining, “I’ve got a friend in the [neighbouring city] who I sometimes go out and do laundry at” [61].

Several tenants spoke about informal, everyday encounters as a foundation for belonging. One tenant “know[s] a few of the neighbours” through a “Community Action Programme, CAP chat” and retains those connections despite not going to CAP chats “these days” [60]. Another described how everyday greetings helped build familiarity:

“When I go to [food distribution event] or I go to the computer room and everyone’s chatty… there’s not one person that I haven’t got a response of ‘Hi’ or anything after I said it to them”.[62]

Facilities and activities provided on site also contributed to experiences of belonging and connectedness at Central Park Apartments. One tenant described the importance of connection to their quality of life: “I can tell you that life here is much better because I know lots of people” [63]. They said the Wednesday afternoon tea “basically goes on forever”, drawing the same familiar group each week and offering a consistent social outlet [63]. They describe it as their first step toward being “more social here in these flats”, even though they now attend less often because of work [63]. A neighbour then drew them into morning teas held in a nearby location, where they “enjoyed listening to everybody… enjoyed the interaction” [63]. The same tenant now stays linked in through a weekly computer class (“I definitely hang around and I love it”) and a mix of gardening, exercise at local facilities, blending on-site amenities with external routines to maintain their social ties [63]. One resident reflected on the value of cultural events and shared meals:

“Just generally to see the people from different cultures and exchange views and everything. Quite often they have international cuisines, you can try different food. It is very well organised I must say, this of course is thanks to Council”.[64]

However, not all tenants made use of the on-site provisions. The aforementioned tenant who administrates an external community group noted they “seldom” used the community room, gym space, or outdoor areas [60]. Another described feeling unwelcome in shared spaces because they feel “too… exposed” and vulnerable to harassment: “I know that a lot of the women here do not use the laundry services… because they get approached by men with ulterior motive… You just don’t know who to trust here” [51].

At Daniell Street, a tenant spoke of the importance of “belong[ing] to the community”, and regularly talked to their neighbours [65]. They said that “most days I try to get out of the house” and made use of an array of services in Newtown and beyond, including the City Mission, library, church services, and activities at the Newtown Community Centre [65]. Another tenant got to know neighbours through their child playing with others in the development, having conversations around common interests, and providing assistance to others [66]. In addition, having a child at the local school had connected them to other locals [66].

At Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place, one tenant described everyday neighbourly dynamics:

“Everything’s accessible and the neighbours are all friendly and everyone makes an effort to make it nice… Everyone says hi when you walk past but leaves you alone if you want… if you need help a neighbour… yeah”.[67]

Another tenant there spoke about participating in a regular support group where members shared life experiences and supported one another:

“Well, we’ve all got [an illness], and we can all relate to each other. We don’t dwell on it if you’re not feeling too well one particular day, you can still go there’s no rules, you don’t have to paint. If you want to just sit there and talk you can. It’s really quite therapeutic. We’ve got a good bonding. A sense of belonging there”.[58]

Taken together, these accounts suggest that belonging and connectedness can be fostered through structured activities as well as through more informal, everyday interactions; and are shaped by the availability of shared spaces and/or shared experiences, the presence of social norms of respect and care, and the willingness of tenants to participate when they feel safe and welcomed enough to do so.

4. Discussion

4.1. Aligning Provider Intentions with Tenant Realities

To ground the discussion, Table 5 synthesises provider change theories, site- and neighbourhood-level provision, and tenant-reported outcomes across the three sites. As Table 5 indicates, provider aspirations for placemaking do not necessarily translate into the built or operational environment, nor into the tenant experiences they aim to support. Central Park Apartments combines a high accessibility index score—indicating strong neighbourhood access to shops, parks, health services, and public transport—with a high level of on-site community infrastructure and a range of coordinated social and operational supports, exemplifying TTM’s structured, participatory approach to placemaking. Daniell Street and ŌCHT’s Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place both sit in neighbourhoods with medium accessibility scores, yet offer only low and low-mid on-site provision, respectively. Despite these contrasts, tenant survey scores on safety, belonging, and connectedness were statistically indistinguishable across the three sites. This is consistent with some of the evidence base, including for older people (noting that the participant sample in this study skewed older). For example, for older Americans, objective and perceived neighbourhood accessibility has been shown to have no association with social support or loneliness [68]. Research in AoNZ has shown that, although older people with access to shared spaces valued them, social connections were mostly maintained through hosting people in their own home, visiting others, and attending church and other activities, rather than through visiting local amenities [69].

Table 5.

Alignment of provider change theories, site- and neighbourhood-level provision, and tenant-reported outcomes across case study sites.

These findings may seem counterintuitive due to understandings common in the broader literature on both neighbourhood and on-site amenities. Neighbourhood interventions to enhance public spaces increase neighbourhood satisfaction, wellbeing, and social connections [70,71,72], and convenient access to amenities supports wellbeing and social connectedness for public housing tenants (and others) [9,73]. On-site housing amenities such as gardens and community rooms are highly valued by residents [74,75,76,77,78,79], and some studies have shown that their presence and quality is associated with positive outcomes like wellbeing and social connectedness [80,81,82].

However, further consideration reveals that the findings presented here do support this broader literature, in that they illustrate how sites with lower-than-ideal accessibility scores or on-site provision can still be relatively accessible in certain ways. OCHT’s Whakahoa Village/Gowerton site has low-mid on-site provision, yet many interviewees expressed their enjoyment of socialising at on-site park benches and spending time in on-site green space. TTM’s Daniell Street has only a medium accessibility score, but, for tenants who are mobile, their home is a short 8–15 min walk to a library, community centre, and shops, all of which interview participants regularly visited. Together, this indicates that housing sites and their surrounding neighbourhoods—as illustrated by the case studies investigated here—work together to enable people to meet their social, placemaking, and wellbeing needs.

Tenant interviews also illuminate other complexities. At Central Park Apartments, many tenants expressed appreciation for secure buildings, and for a range of amenities and activities, but others described feeling unsafe due to neighbours having arguments or mental health episodes and other social tensions. This suggests the benefit of a single-site permanent support housing model for some tenants [73,83]. Similar experiences emerged at the leaner sites, suggesting that even where built and social infrastructure are in place, tenant wellbeing may still be affected by unpredictable or unresolved social dynamics. These findings reinforce the view that the impact of placemaking efforts relates not only to what is provided but also to how shared spaces are perceived, experienced, and negotiated in everyday life over time. These perceptions and interactions—whether individual or collective—are not necessarily stable, and may shift in response to changing social or environmental dynamics, or institutional arrangements beyond the control of housing providers [84,85,86].

ŌCHT’s integration-oriented change theory provides a contrasting lens on the same data. Rather than investing heavily in on-site community infrastructure, the provider focuses on locating housing in well-connected neighbourhoods and supporting tenants to engage with existing services and resources. Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place, reflecting this model, combines medium neighbourhood accessibility with low-to-mid on-site provision. Survey scores at this site were similar to those at Central Park Apartments—despite the latter having both higher accessibility and more extensive on-site infrastructure—suggesting that neither location nor amenity provision alone can explain differences in tenant-reported experiences of safety, belonging, or connectedness. Supplementary interviews with a sub-sample of Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place tenants help contextualise these findings. Several residents spoke positively about the site’s accessibility, neighbourly culture, and informal social exchanges, including gifting home-grown flowers or participating in local art groups. Others expressed ambivalence or discomfort in the surrounding neighbourhood—particularly at night—or described incidents involving antisocial behaviour that undermined their sense of safety.

This cross-site pattern—where tenants valued secure buildings, provision of spaces and services, but reported mixed experiences of safety, belonging, and connectedness—held across both ŌCHT’s integration-oriented model and TTM’s structured, participatory placemaking approach. While Central Park Apartments offered more on-site facilities and programming, and Whakahoa Village/Gowerton Place encouraged informal connections through smaller-scale, neighbourly interactions, tenants’ survey responses showed no significant differences in reported experiences of social connection or belonging. Interview data further suggested that these experiences were shaped less by the quantity of provision than by the quality of everyday interactions and the social dynamics within shared spaces. Connecting and belonging in a community housing context is not guaranteed by access to community infrastructure, whether on-site or nearby; this complex situatedness in relation to people and place warrants further research.

4.2. Study Limitations

These findings should be read as indicative rather than definitive. While they offer insights into relationships between provider intentions and tenant experiences, they also highlight the complexity of measuring impact from placemaking efforts, which cannot capture the full diversity of perspectives or practices across the public and community housing sector. The study draws on two uneven strands of data. On the provider side, analysis is based on twelve staff interviews and a limited number of documents across four CHPs, with in-depth case studies focused on just two of these providers. Interview participants did not include the full range of provider staff and were skewed more toward those in management or leadership positions, meaning the views of frontline workers and contractors are limited or excluded in this account of organisational intent. Provider perspectives are therefore partial and shaped by internal narratives and positional authority and were not corroborated with systematic data on implementation or outcomes.

Tenant data comes with its own significant limitations, with the sample reflecting only part of the full diversity of tenant experiences. The survey reached 113 tenants across three case study sites—a fraction of the total tenant population—and relied on voluntary participation, most likely to be by those who had the time and inclination to respond. This reflects the housing mix at case study sites, which are predominantly studio or one-bedroom units (with a small number of two-bedroom units). These sites tend to house older, single-person households, whereas many Māori and Pacific tenants in public housing live in larger family households requiring more bedrooms. As such, while the survey participants may be broadly representative of the tenant populations at these sites, they are not representative of the public and community housing population as a whole.

Māori and Pacific tenants were under-represented in the sample, despite making up a significant proportion of AoNZ’s public and community housing population [14,27,35]. This limits the applicability of findings and the proposed framework to these groups, as it risks masking unmet needs, overlooking within-group diversity, and failing to account for the intersection of ethnicity with other factors such as age, household composition, and migration history. For Pacific tenants, undersampling means the research likely does not capture the cultural priorities and practices or family structures that can shape their experiences of placemaking. For Māori, as tāngata whenua and Treaty partners, under-representation raises additional concerns. It risks undermining Te Tiriti commitments and principles of data sovereignty, which uphold Māori rights to have research data be relevant, equitable, and useful for Māori communities. Future research on placemaking and community infrastructure in public and community housing should, where possible, adopt kaupapa Māori and Pacific-led approaches that centre these perspectives from the outset. To help address this important limitation here, the below-proposed framework has been developed with reference to Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers [87] and its underpinning Whakawhanaungatanga Māori Wellbeing Model [38], and to principles underpinning Pacific worldviews [39].

Overall, the participant sample was skewed toward older, largely single-person households. More than two-thirds of respondents at each site were aged 55 or over, and most lived without children. Diverse cultures, families, younger adults, and children were under-represented—groups whose needs and experiences of placemaking are likely to differ in important ways. Most respondents were unemployed and on low incomes, and tenant participants from Central Park Apartments were predominantly male.

The limited sample means that the survey analysis is underpowered and unlikely to detect anything less than large effect sizes, increasing the likelihood of Type II statistical errors (to considerably more than the conventionally acceptable likelihood of 20%) [88]. Given that many factors are likely to influence people’s perceptions of their area and their sense of belonging to their neighbourhood, provider approaches to placemaking are expected to make only a small contribution to these overall experiences. Therefore, it cannot be determined whether the failure to reject the null hypothesis is due to similarities in the study sites and tenant experiences, or to false negatives where real-world differences are too small to be detected within the sample. However, the sample does reflect a population group for whom social connectedness is particularly important [89,90]. With an ageing population and rising housing costs in AoNZ and globally, the experiences of older tenants in secure public and community housing are increasingly relevant [91,92].

The study’s cross-sectional design provides a snapshot in time and cannot track change or causality. Limitations constrain the ability to explain why tenant-reported experiences of safety, belonging, or connectedness are similar or different across sites. All outcomes were self-reported and not verified through independent measures such as incident data or observation. While the three case study sites were selected to reflect provider approaches in relation to geography, built form, and community infrastructure provision, they represent only a narrow slice of community housing in AoNZ. Findings should therefore not be generalised to other locations, tenant groups, or organisational models without further investigation. Future research would benefit from larger, more inclusive tenant samples, longitudinal data, and a broader cross-section of provider voices to more fully understand how and why placemaking strategies are experienced and enacted, from theory to practice.

4.3. Placemaking Decision Framework

Drawing on the combined empirical insights from the case studies and relevant literature, a six-stage Placemaking Decision Framework (Table 6) is presented as an empirically grounded synthesis. It is intended as a prototype that translates observed patterns and provider/tenant insights into actionable steps; it has not been formally validated. While adaptable to international contexts, the framework is grounded in the AoNZ context, where public and community housing providers carry obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi to partner with mana whenua and uphold Māori rights to participation and self-determination. Globally, comparable commitments exist in Treaty relationships, Indigenous rights frameworks, and evolving community development practices.

Table 6.

Placemaking Decision Framework.

The first stage—partnership, co-design, and engagement—is foundational and continuous. Rather than a discrete step, it frames how all other stages are undertaken. Meaningful engagement from the outset, including shared governance or partnership arrangements, can support culturally responsive design, build trust, and lead to more durable placemaking outcomes. Recognising Indigenous and community partners early, and resourcing them to participate meaningfully, is central to meeting Te Tiriti o Waitangi (or comparable) obligations and strengthening legitimacy across the development process.

Concept design is where shared values are translated into spatial and social intentions. This includes physical elements like community rooms, shared spaces or gardens, but also the anticipated uses of those spaces, such as support services, creative programmes or everyday gatherings. Design development should test and further explore these intentions to ensure that spaces are well located, flexible, and usable, and that the complementary social infrastructure can be resourced and is viable. This includes clarifying the staffing, governance, and operational plans that will support ongoing use. Physical infrastructure alone is not enough—spaces must also be activated, socially and culturally embedded, and nurturing of tenant agency, if they are to be safe and help foster belonging and connection [2,93]. Consenting and approvals formalise what will be delivered and how. In AoNZ, this includes engaging with planning authorities and demonstrating that mana whenua have been meaningfully involved, with cultural, community, and environmental impacts addressed [94]. In other contexts, heritage protections, equity assessments, or community consultation requirements may play a similar role [95].

Construction and integration of new buildings, spaces, and their inhabitants sit together. High-quality built outcomes matter, but so do the processes that lead to them. Construction activity, if poorly managed, can damage relationships with neighbours before new residents even arrive. Transparent communication, respectful site practices, and visible accountability during the build phase help foster goodwill and lay the groundwork for positive community reception [18]. Integration is equally shaped by how new tenants are welcomed and supported. Coordinated move-in processes, early activation of shared spaces, and a staff presence that fosters familiarity can support tenants to settle and begin forming connections [96,97]. Several tenant participants in this study described early experiences—positive or negative—that had a lasting impact on their sense of comfort and trust. Monitoring and evaluation support learning across projects, place, and time [28,96]. As findings from this study suggest, infrastructure does not automatically generate belonging or connection. Post-occupancy evaluation—including both quantitative usage data and qualitative tenant feedback—can help providers understand what is working, what is not, and why—not just within housing [98], but in the shared spaces (and activities) surrounding it [74,77,99]. This stage can also inform future upgrades or investment—physical or operational—at a given site, ensuring that placemaking remains responsive over time.

Accordingly, readers should treat the framework as a grounded starting point for practice and inquiry, to be adapted and evaluated in situ. The framework should be tested and refined through reflective practice and further research. It offers a starting point for a structured yet adaptable process to guide public and community housing providers. It highlights the importance of not only delivering high-quality built outcomes, but also ensuring the processes that underpin design, construction, and tenant integration are inclusive, supportive, and socially and culturally responsive. While grounded in AoNZ’s policy and Treaty context, the framework can be adapted to settings with similar commitments to equity, participation, and Indigenous or community self-determination.

4.4. Future Research

There is considerable scope to build on the indicative findings presented here. Longitudinal research would strengthen understandings of how safety, belonging, and connectedness change over time, and whether those shifts can be attributed to specific placemaking or infrastructure interventions. In addition to tracking these outcomes, future studies should investigate the underlying reasons for similarities and differences in tenant experiences—clarifying how and why placemaking strategies are experienced and enacted, and how these processes translate from theory to practice. Repeated survey and interview cycles, paired with post-occupancy evaluations, would allow researchers to trace both measurable outcomes and lived experience across different phases of occupancy.

More inclusive and culturally grounded research is also needed (for example, see [74]). Māori and Pacific tenants were under-represented in this study relative to their presence in the public and community housing system. This under-representation reflects broader participation barriers for these groups, and highlights the need for research approaches that are designed from the outset to reflect their values, priorities, and lived realities. Kaupapa Māori research, underpinned by the philosophies and principles of te ao Māori (Indigenous world), centres Māori ways of knowing, being, and doing in all stages of the research process [100]. Applied here, such an approach would guide the design, engagement, analysis, and use of research so that it upholds whakapapa (genealogical connection), whanaungatanga (relationship building), manaakitanga (care and hospitality), kaitiakitanga (guardianship), and tino rangatiratanga (self-determination). In practical terms, this could involve early and sustained consultation with Māori communities and housing providers, over-sampling to ensure adequate representation, and relational, kanohi ki te kanohi (face-to-face, in-person) engagement to build trust. Pacific-led research approaches share similar commitments to cultural integrity, relationality, and collective wellbeing, and would embed principles such as vā (relational space), alofa (love and compassion), fa’aaloalo (respect), and reciprocity into research design and delivery. This could involve partnering with Pacific researchers and community leaders to co-design methods, ensuring research contexts and processes are culturally safe, and valuing collective rather than solely individual perspectives.

Such approaches would help generate findings that are more accurate, relevant, and useful to Māori and Pacific tenants, and that contribute to Treaty commitments, equity, social and spatial justice goals. Similar approaches are relevant in other international contexts where Indigenous or historically marginalised communities are central to public and community housing systems. Comparative research across housing providers, cities, countries, and policy settings would help clarify which combinations of built infrastructure, social programming, and partnership approaches (including Indigenous and other culturally grounded approaches) most consistently support tenant wellbeing. Case study comparisons could identify not just what works, but under what conditions, for whom, and why. Complementing self-reported data with other measures will help to create a fuller understanding. These might include police call-outs, space-use observations, maintenance request patterns, participation rates in events or programmes, or staff records of tenant engagement. Unlike the accessibility scoring and spatial analysis already employed in this study, such data could offer insight into how and why spaces are used and experienced over time, and how community infrastructure is maintained and activated in practice.

Finally, the proposed framework itself warrants further testing and refinement. While grounded in development logic and shaped by evidence from literature, four CHP organisations and three case study sites, its adaptability should be trialled and evaluated in situ across more diverse projects and contexts. Feedback from practitioners, tenants, and Indigenous or community partners could help strengthen its practical value and cultural integrity.

5. Conclusions

Community housing providers increasingly recognise that quality housing extends beyond the dwelling to embrace shared spaces, community infrastructure, and the everyday interactions that help to foster safety, belonging, and connectedness. The findings presented here offer a partial view. Across four providers, change theories converged on strengthening tenant connections to people and place, yet diverged in method: TTM pursued more structured, participatory placemaking; ŌCHT favoured an integration-oriented model that leverages existing services and resources; SASH embedded housing within holistic wrap-around services; and DHT adopted an opportunity-driven, location-first stance. Across the three case study sites examined in depth, higher levels of on-site community infrastructure did not translate into clearly stronger feelings of safety, belonging, or connectedness amongst tenants. However, this does not imply that placemaking efforts are irrelevant. Rather, it reflects the study’s limited sample and design, and the complexities of measuring impact. All outcome measures were self-reported, and the tenant sample was small, skewed toward older, mostly single-person households, and under-represented Māori, Pacific, families, and younger tenants.

More fundamentally, the findings reflect a comparison between approaches that each involve some degree of placemaking or investment in community infrastructure—whether through on-site provision or integration with surrounding neighbourhoods, or a combination of both. The study did not compare these to another possible approach: providers that make no investment in placemaking and regard themselves purely as landlords. The absence of a comparison group with no placemaking investment limits conclusions about its added value; future research could address this by including providers that adopt a more strictly landlord-focused role. Rather than offering definitive evidence, the study signals possibilities, prompts reflective practice, and suggests further avenues for research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/architecture5030069/s1, Figure S1: Life satisfaction scores for all respondents in Daniell Street, Gowerton Place/Whakahoa Village and Central Park Apartments; Figure S2: Area suits needs for whole sample; Figure S3: Overall satisfaction with area in terms of ability to travel; Figure S4: Overall sense of belonging to neighbourhood; Figure S5: Respondents who belong to neighbourhood group; Figure S6: Overall ease of access to green space; Figure S7: Overall feelings of safety walking alone after dark in neighbourhood; Figure S8: Life satisfaction scores by housing group; Figure S9: Area suits needs by housing group; Figure S10: Satisfaction with area in terms of ability to travel, by housing group; Figure S11: Sense of belonging to neighbourhood; Figure S12: Belonging to neighbourhood group; Figure S13: Ease of access to green space; Figure S14: Feelings of safety walking alone after dark in neighbourhood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V.O.; methodology, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C., A.L. and P.H.-C.; software, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C. and A.L.; validation, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C. and A.L.; formal analysis, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C. and A.L.; investigation, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C. and A.L.; resources, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C., A.L., P.H.-C. and L.L.; data curation, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.O. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, C.V.O., K.W., E.R., E.C., A.L., P.H.-C. and L.L.; visualization, C.V.O.; supervision, C.V.O.; project administration, C.V.O.; funding acquisition, P.H.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment—Grant number: 20476 UOOX2003.

Institutional Review Board Statement