Analysis of One-Stop-Shop Models for Housing Retrofit: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Retrofit at Scale

1.2. Barriers to Retrofit

1.3. One-Stop Shops in Housing Retrofit

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy, Inclusion Criteria and Scope

2.2. Selection of Studies

2.3. Data Items

3. Results

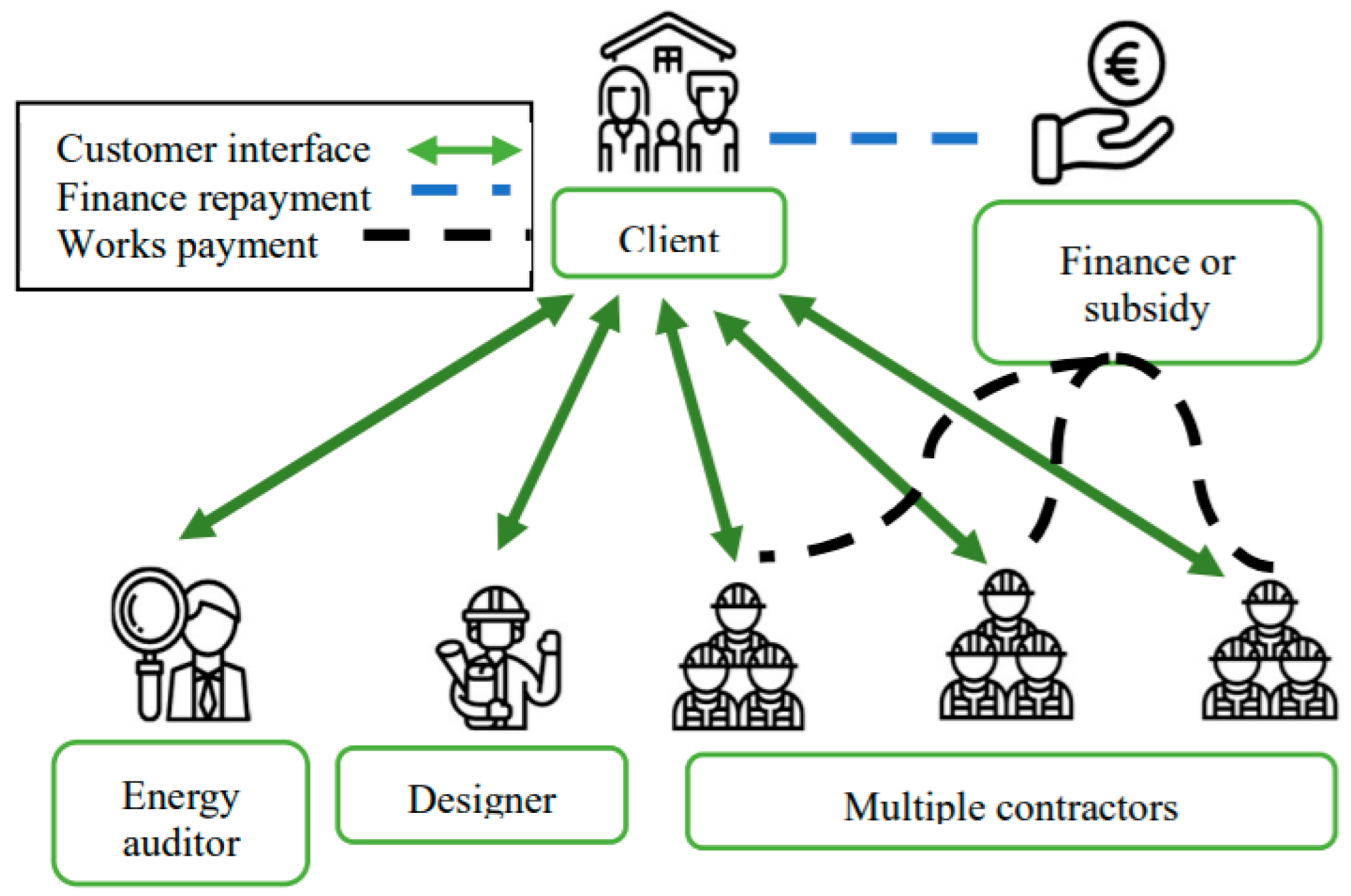

3.1. Level of Responsibility

3.2. Ownership

3.3. Delivery Method

4. Discussion

4.1. Responsibility Levels of One-Stop Shops

4.2. Ownership of One-Stop Shops

4.3. Delivery Methods of One-Stop Shops

4.4. Recommendations for Retrofit at Scale

4.5. Limitations and Implications of the Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Climate Change Act 2008; UK Government: London, UK, 2019.

- DESNZ. 2022 UK Provisional Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Department for Energy Security and Net Zero: London, UK, 2022.

- RICS. Retrofitting to Decarbonise UK Existing Housing Stock—RICS Net Zero Policy Position Paper; Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- BRETrust. The Housing Stock of the United Kingdom; Building Research Establishment: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UKGBC. Database on Residential Properties; United Kingdom Green Building Council: London, UK, 2024.

- Skidmore, C.; McWhirter, S. Mission Retrofit; United Kingdom Green Building Council: London, UK, 2023.

- ONS. Dwelling Stock: By Tenure, United Kingdom, as at 31 March; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2022.

- Holms, C. Demand: Net Zero Tackling the Barriers to Increased Homeowner Demand for Retrofit Measures; Citizens Advice: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fylan, F.; Glew, D. Barriers to domestic retrofit quality: Are failures in retrofit standards a failure of retrofit standards? Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 31, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. Business models for residential retrofit in the UK: A critical assessment of five key archetypes. Energy Effic. 2018, 11, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickaby, P. The Importance of Standards for Safe Energy Retrofit|A BSI White Paper; The British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfield, P. Each Home Counts; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG): London, UK, 2016.

- Cicmanova, J.; Maraquin, T.; Eisermann, M. How to Set up a One-Stop-Shop for Integrated Home Energy Renovation? Energy Cities: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Energy Authority Of Ireland. One Stop Shop Service. Available online: https://www.seai.ie/grants/home-energy-grants/one-stop-shop (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- McGinley, O.; Moran, P.; Goggins, J. Key Considerations. In The Design of a One-Stop-Shop Retrofit Model; Civil Engineering Research: Cork, Ireland, 2020; Available online: https://sword.cit.ie/ceri/2020/13/5 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Bertoldi, P.; Boza-Kiss, B.; Della Valle, N.; Economidou, N. The role of one-stop shops in energy renovation—A comparative analysis of OSSs cases in Europe. Energy Build. 2021, 250, 111273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biere-Arenas, R.; Spairani-Berrio, S.; Spairani-Berrio, Y.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C. One-Stop-Shops for Energy Renovation of Dwellings in Europe—Approach to the Factors That Determine Success and Future Lines of Action. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaini, A.; Croci, E.; Molteni, T. Boosting energy home renovation through innovative business models: ONE-STOP-SHOP solutions assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.; Marthe, P.; Stephane, G.; Claire, O.; Marion, B. European market structure for integrated home renovation support service: Scope and comparison of the different kind of one stop shops. AIMS Energy 2023, 11, 846–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, R.; Mlecnik, E.; Visscher, H.; Qian, Q. Integrated home renovation services as a means to boost energy renovations for homeowner associations: A comparative analysis of service providers’ business models. Energy Build. 2024, 320, 114589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biere-Arenas, R.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C. One Stop Shops on Housing Energy Retrofit. European Cases, and Its Recent Implementation in Spain. In Sustainability in Energy and Buildings 2022; Littlewood, J., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panakaduwa, C.; Coates, P.; Munir, M. Evaluation of Government Actions Discouraging Housing Energy Retrofit in the UK: A Critical Review. In Proceedings of the European Energy Markets 2024, Istanbul, Turkey, 10–12 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.; Mahapatra, K.; Pardalis, G. Strategies for deep renovation market of detached houses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimigharehbaghi, S.; Qian, Q.K.; Meijer, F.M.; Visscher, H.J. Unravelling Dutch homeowners’ behaviour towards energy efficiency renovations: What drives and hinders their decision-making? Energy Policy 2019, 129, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunikka-Blank, M.; Galvin, R. Irrational homeowners? How aesthetics and heritage values influence thermal retrofit decisions in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrova, Y.; Papachristos, G.; Cooper, A. Process perspective on homeowner energy retrofits: A qualitative metasynthesis. Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, J. EnerPHit: A Step by Step Guide to Low Energy Retrofit; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Energiesprong. Energiesprong Global Alliance Explained. Available online: https://energiesprong.org/about/ (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Volt, J.; McGinley, O. Underpinning the Role of One-Stop Shops in the EU Renovation Wave; BPIE—Buildings Performance Institute: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PAS 2035:2023; Retrofitting Dwellings for Improved Energy Efficiency—Specification and Guidance. The British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2023.

- Brook, M. Estimating and Tendering for Construction Work, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimigharehbaghi, S. Understanding the Decision-Making Process in Homeowner Energy Retrofits. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Delft, Delft, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørneboe, M.G.; Svendsen, S.; Heller, A. Using a One-Stop-Shop Concept to Guide Decisions When Single-Family Houses Are Renovated. J. Archit. Eng. 2017, 23, 05017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardalis, G.; Mahapatra, K.; Mainali, B.; Bravo, G. Future Energy-Related House Renovations in Sweden: One-Stop-Shop as a Shortcut to the Decision-Making Journey. In Advances in Sustainability Science and Technology; Howlett, R.J., Littlewood, J.R., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Duffy, A. A Digital Support Platform for Community Energy: One-Stop-Shop Architecture, Development and Evaluation. Energies 2022, 15, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Mazaheri, A.; Mainali, B.; Mahapatra, K. Integrating Digital Tools in One-Stop-Shop Business Models for Climate-Smart Single-Family Home Renovation in the European Union. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Built Environment and Urban Transition, Växjö, Sweden, 12–13 October 2023; ISBN 9789180820424. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira, M.M.; Gouveia, J.P. A Sequential Multi-Staged Approach for Developing Digital One-Stop Shops to Support Energy Renovations of Residential Buildings. Energies 2022, 15, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddiki, M.; Bennadji, A.; Laing, R.; Gray, D.; Alabid, J.M. Review of Existing Energy Retrofit Decision Tools for Homeowners. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan-Sharif, S.; Mura, P.; Wijesinghe, S.N.R. A systematic review of systematic reviews in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, K.; Thayaparan, M.; Kaluarachchi, Y.; Pathirage, C. Challenges Faced by Marginalized Communities in a Post-Disaster Context: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardalis, G.; Mahapatra, K.; Bravo, G.; Mainali, B. Swedish House Owners’ Intentions Towards Renovations: Is there a Market for One-Stop-Shop? Buildings 2019, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardalis, G.; Talmar, M.; Keskin, D. To be or not to be: The organizational conditions for launching one-stop-shops for energy related renovations. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copiello, S.; Donati, E.; Bonifaci, P. Energy efficiency practices: A case study analysis of innovative business models in buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 313, 114223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardalis, G.; Mainali, B.; Mahapatra, K. One-stop-shop as an innovation, and construction SMEs: A Swedish perspective. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 2737–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, P.; Economidou, M.; Palermo, V.; Boza-Kiss, B.; Todeschi, V. How to finance energy renovation of residential buildings: Review of current and emerging financing instruments in the EU. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2021, 10, e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teli, D.; Dimitriou, T.; James, P.A.B.; Bahaj, A.S.; Ellison, L.; Waggott, A. Fuel Poverty-Induced ‘Prebound Effect’ in Achieving the Anticipated Carbon Savings From Social Housing Retrofit. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 37, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Less, B.; Walker, I.S.; Casquero-Modrego, N. Emerging Pathways to Upgrade the US Housing Stock: A Review of the Home Energy Upgrade Literature; Berkeley Lab: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.; Yordi, S.; Besco, L. The Role of Pilot Projects in Urban Climate Change Policy Innovation. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 48, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Energy Authority Of Ireland. One Stop Shop Registered Providers. Available online: https://www.seai.ie/find-grants-and-contractors/find-contractors/registered-one-stop-shops (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Pardalis, G.; Mahapatra, K.; Mainali, B. Comparing public- and private-driven one-stop-shops for energy renovations of residential buildings in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askim, J.; Fimreite, A.L.; Moseley, A.; Pedersen, L.H. One-stop Shops for Social Welfare: The Adaptation of an Organizational Form in Three Countries. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1451–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrorie, R.; Arbabi, H.; Eadson, W.; Hanna, R.; McCluskey, K.C.; Simpson, K.; Wade, F. Support Place-Based and Inclusive Supply Chain, Employment and Skills Strategies for Housing-Energy Retrofit. In Strengthening European Energy Policy; Crowther, A., Foulds, C., Robison, R., Gladkykh, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozer, L.; MacRae, H.; Smit, E. Achieving Deep-Energy Retrofits for Households in Energy Poverty. Build. Cities 2023, 4, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C. Putting one-stop-shops into practice: A systematic review of the drivers of government service integration. Evid. Base J. Evid. Rev. Key Policy Areas 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, J.; Childs, S. The Cynefin framework: A tool for analyzing qualitative data in information science? Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2013, 35, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panakaduwa, C.; Coates, P.; Munir, M. One-Stop Shop Solution for Housing Retrofit at Scale in the United Kingdom. Architecture 2025, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Economic | High initial cost of retrofit and longer payback. Split interests between tenants and landlords. |

| 2 | Informational | Lack of awareness about the retrofit process and benefits. Uncertainty of the benefits and unintended consequences. Informational asymmetry. |

| 3 | Regulatory | Inconsistencies in policies. Complex administrative procedures. |

| 4 | Behavioural | Resistance to change. Social influence. Lack of trust in the retrofit. |

| 5 | Technical | Disruption to the residents. Lack of skills to deliver retrofit at scale. Market fragmentation. |

| Title | Authors | Year | Article Type | Source/Journal | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Business models for residential retrofit in the UK: A critical assessment of five key archetypes | Donal Brown | 2018 | Journal article | Energy Efficiency | [10] |

| 2 | Swedish House Owners’ Intentions Towards Renovations: Is there a Market for One-Stop-Shop? | Georgios Pardalis, Krushna Mahapatra, Giangiacomo Bravo and Brijesh Mainali | 2019 | Journal article | Buildings | [42] |

| 3 | The role of one-stop shops in energy renovation—A comparative analysis of OSSs cases in Europe | Paolo Bertoldi, Benigna Boza-Kiss, Nives Della Valle and Marina Economidou | 2021 | Journal article | Energy & Buildings | [16] |

| 4 | Strategies for the deep renovation market of detached houses | Brijesh Mainali, Krushna Mahapatra and Georgios Pardalis | 2021 | Journal article | Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | [23] |

| 5 | To be or not to be: The organisational conditions for launching one-stop-shops for energy related renovations | Georgios Pardalis, Madis Talmar and Duygu Keskin | 2021 | Journal article | Energy Policy | [43] |

| 6 | One-Stop-Shops for Energy Renovation of Dwellings in Europe—Approach to the Factors That Determine Success and Future Lines of Action | Rolando Biere-Arenas, Silvia Spairani-Berrio, Yolanda Spairani-Berrio and Carlos Marmolejo-Duarte | 2021 | Journal article | Sustainability | [17] |

| 7 | Boosting energy home renovation through innovative business models: ONE-STOP-SHOP solutions assessment | Annamaria Bagaini, Edoardo Croci and Tania Molteni | 2022 | Journal article | Journal of Cleaner Production | [18] |

| 8 | A Sequential Multi-Staged Approach for Developing Digital One-Stop Shops to Support Energy Renovations of Residential Buildings | Miguel Macias Sequeira and João Pedro Gouveia | 2022 | Journal article | Energies | [37] |

| 9 | One Stop Shops on Housing Energy Retrofit. European Cases, and Its Recent Implementation in Spain | Rolando Biere-Arenas and Carlos Marmolejo-Duarte | 2023 | Conference paper | Sustainability in Energy and Buildings | [21] |

| 10 | European market structure for integrated home renovation support service: Scope and comparison of the different kinds of one-stop shops | Estay Lucas, Peperstraete Marthe, Ginestet Stephane, Oms-Multon Claire and Bonhomme Marion | 2023 | Journal article | AIMS Energy | [19] |

| 11 | Energy efficiency practices: A case study analysis of innovative business models in buildings | Sergio Copiello, Edda Donati and Pietro Bonifaci | 2024 | Journal article | Energy & Buildings | [44] |

| 12 | Integrated home renovation services as a means to boost energy renovations for homeowner associations: A comparative analysis of service providers’ business models | Ragy Elgendy, Erwin Mlecnik, Henk Visscher and Queena Qian | 2024 | Journal article | Energy & Buildings | [20] |

| Description | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Low | One-stop shops with low responsibility regarding their delivery of services. | [10,18,19,21,37] |

| Medium | One-stop shops, which have a medium level of responsibility over their services. | [10,17,18,19,21,44] |

| High | One-stop shops with a higher level of responsibility for their services. | [10,16,18,19,21,44] |

| Description | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Government | One-stop shops, funded and operated by government-related institutions. | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| Contractor | One-stop shops, operated by retrofit contractors. | [16,17,18,19,20,42,43] |

| Other | One-stop shops, operated independently by other stakeholders such as NGOs or energy companies. | [10,16,18,19,21] |

| Description | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | One-stop shops with a physical presence in a location where people can call over and meet professionals. | [16,19,37] |

| Online | One-stop shops without a physical presence but functioning online. | [10,16,19,37,42] |

| Hybrid | One-stop shops, which have both a physical location and an online presence. | [17,18,37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panakaduwa, C.; Gunasekara, I.; Coates, P.; Munir, M. Analysis of One-Stop-Shop Models for Housing Retrofit: A Systematic Review. Architecture 2025, 5, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030047

Panakaduwa C, Gunasekara I, Coates P, Munir M. Analysis of One-Stop-Shop Models for Housing Retrofit: A Systematic Review. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030047

Chicago/Turabian StylePanakaduwa, Chamara, Ishika Gunasekara, Paul Coates, and Mustapha Munir. 2025. "Analysis of One-Stop-Shop Models for Housing Retrofit: A Systematic Review" Architecture 5, no. 3: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030047

APA StylePanakaduwa, C., Gunasekara, I., Coates, P., & Munir, M. (2025). Analysis of One-Stop-Shop Models for Housing Retrofit: A Systematic Review. Architecture, 5(3), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030047