1. Introduction

Social justice concerns have become increasingly central to architectural practice and education, underscoring the urgent need for innovative methods to address issues like equity, accessibility, and environmental justice in urban environments. These issues are not only critical for fostering inclusive urban spaces but also for preparing future architects to engage with the complexities of socio-spatial dynamics in an increasingly interconnected and inequitable world [

1]. Architectural education provides a unique opportunity to instill social awareness and equip students with the skills to address these challenges through interdisciplinary learning and hands-on urban interventions [

2].

The intersections of architecture, urban design, and social justice have been explored through various lenses, including participatory design, community-driven planning, and Tactical Urbanism. Scholars have highlighted how urban interventions can address systemic inequities by empowering marginalized communities and fostering collaboration among stakeholders [

3,

4]. However, while these approaches demonstrate promise, there remains a critical gap in structured educational interventions that explicitly address social justice issues within architectural curricula [

5]. This gap reflects broader challenges in bridging theory and practice, as well as integrating interdisciplinary methods into design education.

This study addresses these challenges by exploring how collaborative design and participatory research methods can be integrated into architectural education to foster social awareness and community engagement. Drawing on theories such as Lefebvre’s “Right to the City” and Fraser’s concept of participatory parity, it examines the potential of interdisciplinary approaches to enable students to critically engage with real-world inequities and develop actionable solutions. The research posits that interdisciplinary urban interventions offer a practical and impactful framework for addressing these challenges while preparing students for the complexities of professional practice [

6,

7].

The primary research question guiding this study is as follows: How can urban interventions within architectural education effectively address social justice issues?

Additional questions include the following: What role do collaborative design and participatory research play in fostering community engagement? How can these approaches equip students with practical skills for addressing urban inequities?

This study uses a comparative case study framework, focusing on student-led projects in Houston, San Diego, and Amsterdam. These projects address social justice themes such as Art Activism, Tactical Urbanism, environmental justice, and gender equity. By analyzing these cases, this study demonstrates how interdisciplinary and multi-scalar approaches can provide innovative solutions to complex urban problems.

This paper is organized as follows: The Methodology section details the tools and frameworks employed, including digital mapping, poster creation, and case study analysis. The Results section presents findings from student-led projects, emphasizing key outcomes. The Discussion section analyzes these findings in relation to existing literature, highlighting study limitations and areas for future research. Finally, the Conclusion reflects on the broader implications for architectural education and the potential for urban interventions to advance social justice in diverse contexts.

2. Methodology

This study adopts an interpretivist research philosophy to explore social justice in architectural education through comparative case study analysis. We examine student-led projects across different cities to assess the impact of collaborative design on community challenges. Using a multiple case study approach with a cross-sectional time horizon, this study focuses on projects completed within a single academic semester, providing immediate insights into the short-term effects of each intervention.

City Selection: The purposive sampling strategy guided the selection of cities based on their unique social justice challenges. The chosen cities—Houston, San Diego, Burlington, Amsterdam, and Thessaloniki—each represent different social justice themes. For instance, Houston was selected for its relevance to racial and environmental justice, San Diego for Art Activism, and Thessaloniki for gender justice. This diversity allows for a comprehensive examination of urban equity across varied settings, and the students chose these specific case studies to respond effectively to the unique social justice challenges present in each city [

6].

Data Collection: Data were gathered through digital mapping, poster creation, and case study analysis. Student-created artifacts and community feedback were thematically analyzed to capture insights into each project’s social justice focus. The cross-sectional nature of this study limits our ability to assess long-term impacts; additionally, purposive sampling introduces potential selection bias. Future research could address these limitations by expanding the range of cities and adopting a longitudinal approach.

The methodology combines urban design, social science, and digital technology to address social justice issues. Participatory methods, such as community feedback sessions and workshops, deepened students’ understanding of local dynamics and allowed them to create design interventions tailored to the unique social justice contexts of cities like Houston, Burlington, and Thessaloniki.

Project Themes: This comparative framework allowed students to explore different facets of social justice through multiple lenses:

- -

Art Activism in Houston and San Diego: Projects employed digital mapping and poster creation to visualize the impact of Art Activism in fostering community identity and social awareness. Students analyzed graffiti walls, murals, and multimedia expressions to understand their role in challenging stigmas and promoting cross-cultural understanding.

- -

Tactical Urbanism in Burlington, Oak Cliff, and Jersey City: Case study analysis and design interventions examined how Tactical Urbanism initiatives enhance public spaces and social cohesion. Students explored temporary urban interventions like sidewalk extensions and bikeways and assessed their impact on community engagement and street safety.

- -

DIY Practices in Austin and Amsterdam: Projects focused on grassroots efforts and community-led initiatives, employing observational studies, interviews, and design proposals. Students investigated the role of DIY practices in empowering communities to actively shape their environments and address issues such as homelessness and urban agriculture.

- -

Environmental Justice in West Virginia, Houston, and Amsterdam: Through literature review, spatial analysis, and case study examination, students explored environmental injustices in marginalized communities. They assessed the impacts of coal mining, illegal dumping, and unequal access to green spaces on the health and well-being of residents.

- -

Gender Justice in the United States and Iran: Using visual communication and critical analysis, students examined the intersection of architecture and gender justice. They analyzed how architectural spaces serve as platforms for advocacy, referencing movements like the Abortion Rights Movement and the Mahsa Amini protests.

- -

Racial Justice in Houston, Los Angeles, and El Paso: Projects combined qualitative research, policy analysis, and visual storytelling to investigate racial discrimination and violence in urban environments. Students examined incidents of racial injustice to understand their implications for urban planning and community development.

Before delving into each case study, it is essential to understand the broader context of these urban interventions. Together, these case studies illustrate how collaborative design, and research can address complex social justice issues in urban environments, providing concrete examples of how such approaches can drive meaningful community change.

3. Art Activism in Houston and San Diego

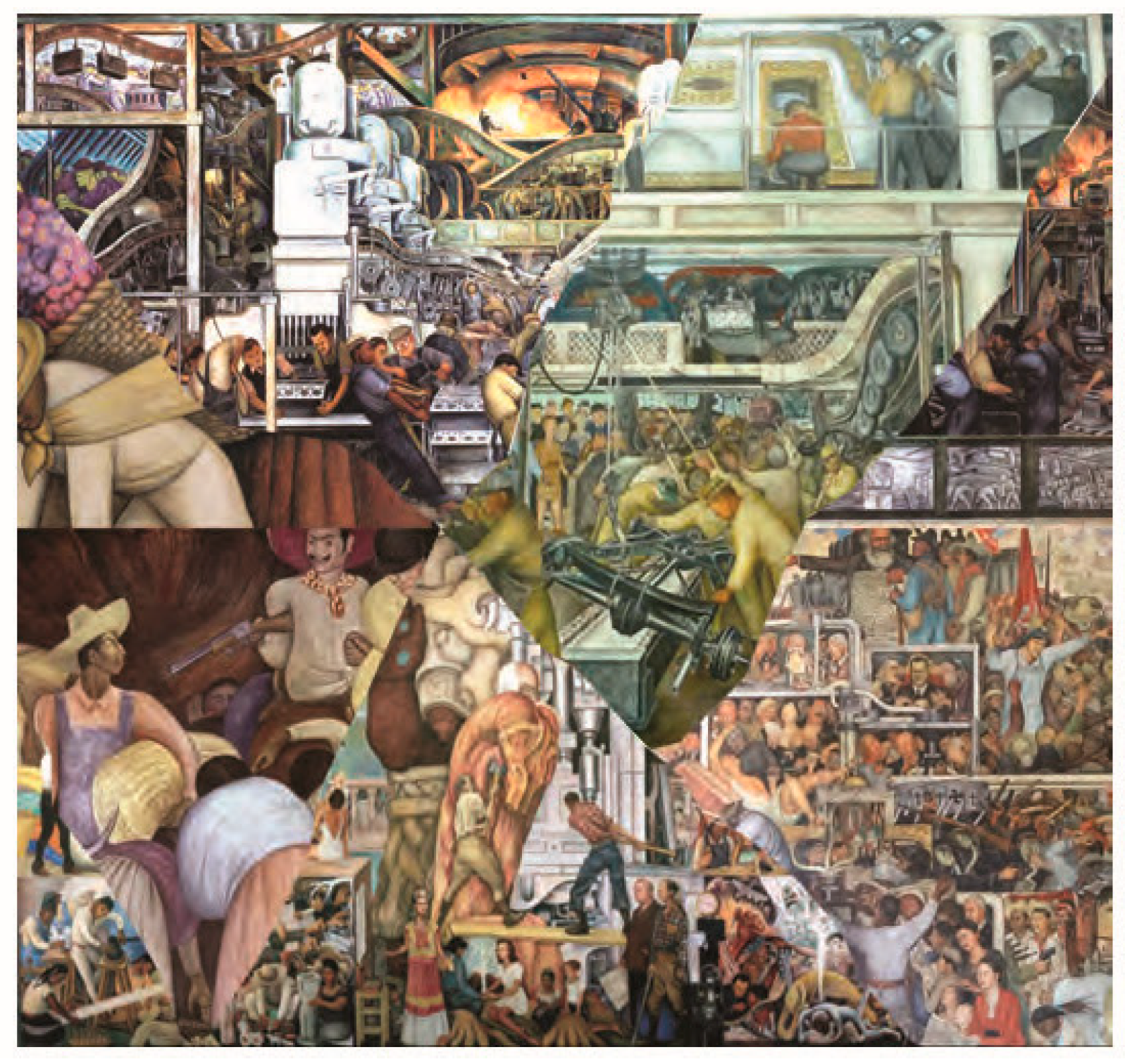

Art Activism is manifested throughout the world. Focusing on the specific cities of Houston, Texas; and San Diego, California, these two cities are no strangers to the manifestation of activism using art. The members Megan M. Reynolds and Chantal Rivas explored and analyzed the case study of Art Activism throughout the semester. Art Activism, present in both cities, is manifested through graffiti walls and murals, writings, music, and films. This movement is known to display community identity, neighborhood cohesion, creativity, education, and sustainability.

To visualize the concept of Art Activism, posters were produced to relay the messages of different case studies acknowledging the importance of this movement.

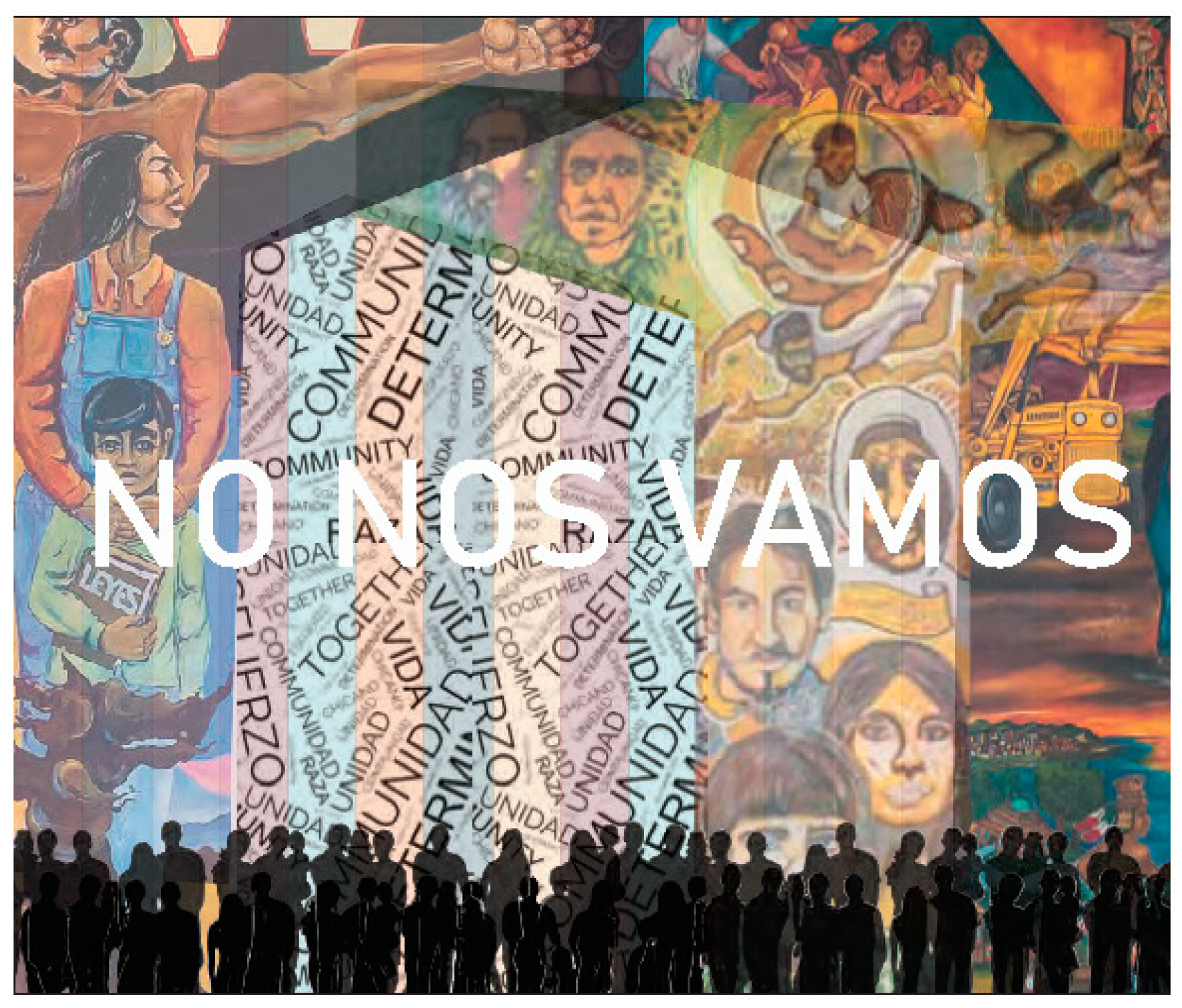

Figure 1 shows the AIA Project depicting self-identity in the immigration community in San Diego. The poster depicts the frustration that may come from being a part of a marginalized group, as the immigrant population is in this part of the world. The hands represent the AIA Project and the help they provide to artists, which helps people represent themselves and not be afraid to tell their stories. The background of the poster is composed of several Art Activism posters, which include some graffiti works which is what started the entire project topic.

The determination of the residents serves as inspiration for

Figure 2, which shows Chicano Park. The phrase “no nos vamos” meaning “we will not leave”—highlighted in white—reflects the solidarity shown through the depiction of a human chain around the bulldozers. The black silhouettes at the bottom of the poster symbolize the struggle that the Chicano community had to endure to retain the space they had long utilized before it was overtaken by the U.S. Government [

7]. Words like “unidad”, “comunidad”, “raza”, and “esfuerzo” are written, translating to unity, community, Hispanic people, and effort, respectively, in English [

8]. Using these words, the students Chantal Rivas and Megan Reynolds encapsulate the essence and values of Chicano Park in San Diego, California. Furthermore, the poster features selected murals from Chicano Park, demonstrating the visual representation of the murals and the stories they convey about the Hispanic community in the area.

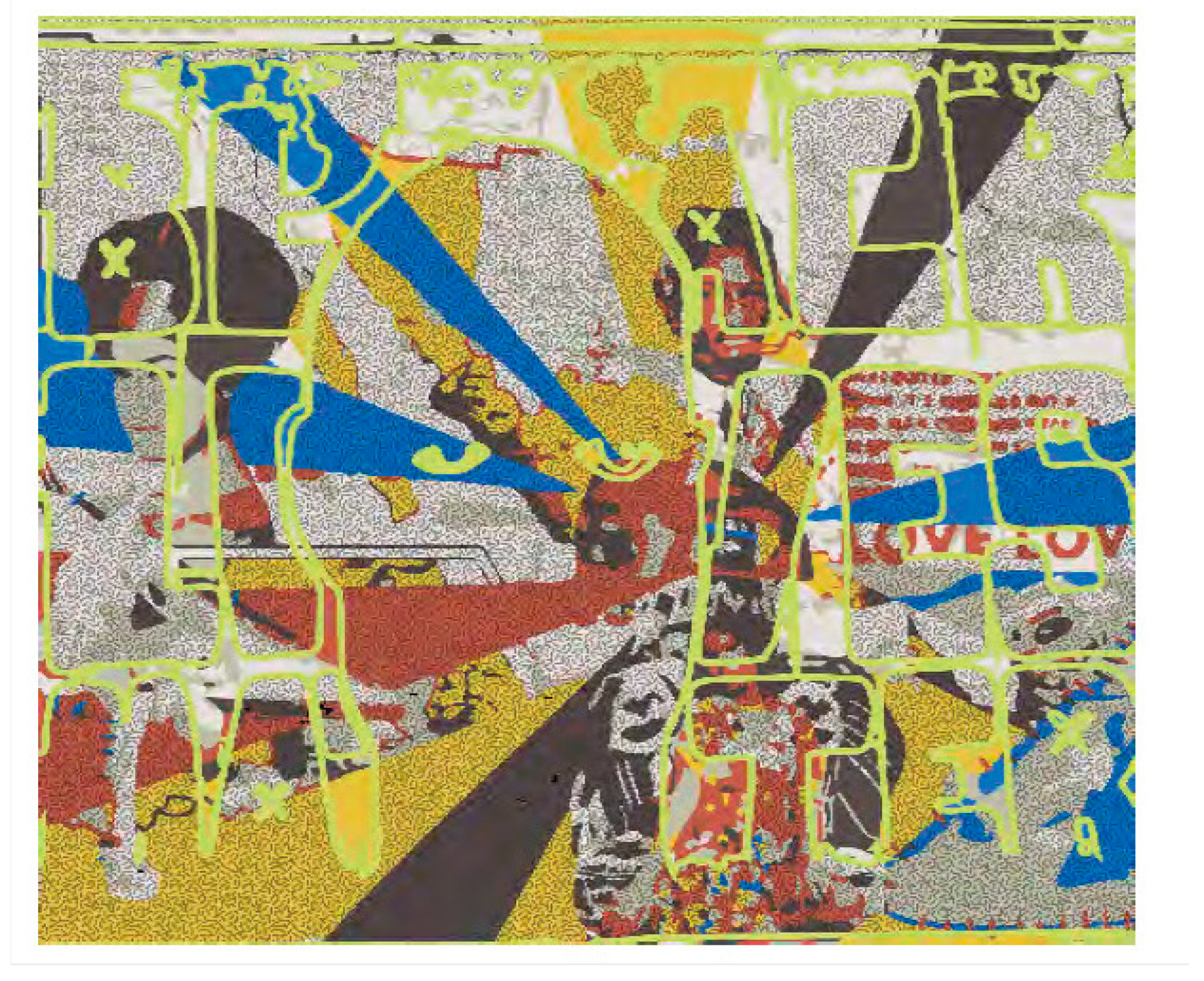

Leo Tanguma’s renowned East End mural, “The Rebirth of our Nationality” [

9], holds significant cultural importance in the Chicano neighborhood. Recently restored to its original state, this 240-foot mural is adorned with the headline “to become aware of our history is to become aware of our singularity”, visible in the background alongside pastel hues of red and green inspired by the Mexican flag. In the lower corner, a muralist can be seen contributing to its restoration. The Mexican American Youth Organization [

10] (MAYO) started the Chicano protests in Houston on February 15, 1970, and this is where the collage’s main image comes from. The collage’s base image is sourced from the Chicano protests in Houston on February 15, 1970, which initiated these protests after Presbyterian church leaders ignored requests for a cultural center and attempted to sell the church building to another congregation [

10]. In response, MAYO protestors occupied the building, organizing history classes, free meals, and fostering positive community interaction. Over 21 days (about 3 weeks), they served more than 40 children daily. Eventually, the congregation that acquired the building continued the services initiated by MAYO activists, leaving a lasting positive impact on the neighborhood.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, UP Art Studio created the Houston Mural Map (

Figure 3) to represent the city’s vibrant art culture. Among its features is “Black Lives Matter”, a mural painted by artist Nicky Davis on Houston’s North Side. This mural portrays George Floyd with the BLM slogan in the background; the image was transformed into a vectorized form in Photoshop, serving as the visible foreground of the collage. The collage’s background predominantly showcases the artwork of Hodge Robert, an artist born in Houston’s Third Ward. Robert’s pieces often encapsulate themes of memory and commemoration and have recently gained recognition as a feature in the Museum of Contemporary Art. It was deemed significant to highlight an activist whose artistic contributions extend beyond street art to gallery exhibitions and collages. The BLM movement has seen significant participation across Houston communities, marking one of the more recent displays of mass activism [

11,

12].

In both Houston and San Diego, Art Activism predominantly centers around celebrating the vibrant Hispanic and Chicano cultures. Graffiti, once stigmatized as a criminal activity, is now increasingly recognized as a form of representation and expression within these communities. The proliferation of art throughout these cities serves as a powerful motivator for individuals to delve deeper into the cultural narratives they encounter. By utilizing art as a medium, stories can be vividly told, enabling people from diverse backgrounds to gain insights into these rich cultures and fostering cross-cultural understanding and appreciation.

4. Tactical Urbanism in Burlington, Oak Cliff, and Jersey City

Tactical Urbanism is a proactive approach focused on enhancing local neighborhoods through short-term initiatives to achieve lasting objectives [

13]. These aims encompass various aspects such as public space, street safety, and social cohesion. Typically employing inexpensive materials, these projects are initiated by community members who seek improvements in their neighborhoods [

13]. While sometimes led by governmental or non-profit entities, community-led projects often serve to advocate for improvements made by governmental officials. This method catalyzes community betterment, adaptable to diverse contexts and locations. Its foundation lies in implementing short-term endeavors to achieve enduring goals [

13]. These projects, which are temporary and budget-friendly, aim to generate long-term improvements within communities. While effective implementation is crucial, initiating change ultimately hinges on taking decisive action. Tactical Urbanism has emerged as a popular approach for addressing imperfections within cities and neighborhoods worldwide, with traction in the United States. To illustrate its effectiveness, we examined three case studies in Burlington, Vermont; Oak Cliff, Texas; and Jersey City, New Jersey. These cities offer compelling examples of how Tactical Urbanism can be applied, the benefits it provides, and the impact it can have on communities.

In the small city of Burlington, where a university contributes to a high percentage of residents walking or biking to school or work, Street Plans, along with the Department of Public Works and Local Motion, initiated the PlanBTV Walk Bike project (Shown in

Figure 1. This project aimed to address mobility obstacles by implementing four short-term projects across busy streets [

14]. These projects included colorful sidewalk extension plazas and various types of bikeways and intersections. The primary objectives were to encourage community involvement in enhancing walking and cycling conditions and to assess the effectiveness of city policies in achieving these improvements.

In Oak Cliff, there is a street called Tyler Street that was once vibrant but fell into disrepair due to years of retail neglect with a focus on automobiles, resulting in numerous urban shortcomings (shown in

Figure 2). These issues included empty lots, abandoned storefronts, rundown buildings, and underutilized parking spaces. In response, a small group of neighborhood activists and artists initiated the Build a Better Block project as part of an art festival. This initiative aimed to transform a four-lane street into a pedestrian-friendly neighborhood in two days [

15]. The project involved creating sidewalk dining, protected bike parking, pop-up shops, and other small-scale amenities. Despite allowing vehicular access during the festival to demonstrate that amenities could still function with traffic, the project showcased how to revitalize a neglected area without relying on angel investors or government agencies.

The final case studies took place in Jersey City, New Jersey, where the city planned to introduce a Pedestrian Enhancement Plan prioritizing pedestrian safety and experience to reduce accidents and fatalities (

Figure 4). Seeking input from citizens, the city collaborated with Fitzgerald & Halliday Inc., a design firm dedicated to community enhancement, and Street Plans to organize six walkability workshops aimed at gathering residents’ feedback to inform the plan [

16]. These workshops, held in three different locations across the city, involved Street Plans leading three parklets where surveys were distributed by Fitzgerald & Halliday Inc. The temporary curb extensions designed by Street Plans included public feedback boards, wayfinding signage, planters, and colorful paint. These extensions allowed residents to experience a potential safety project firsthand while contributing input to the Pedestrian Enhancement Plan.

All these case studies share a common objective: to enhance the communities where people live. Communities thrive on the active participation of their residents, and it is incumbent upon them to contribute to the improvement of their neighborhoods, underscoring the essence of Tactical Urbanism as a proactive approach focused on action.

5. DIY Practices in Austin and Amsterdam

DIY practices are prevalent globally, often adopted by individuals and communities seeking to actively transform and empower their environments for the betterment of their community. Through these grassroot initiatives, environments are improved in alignment with the unique needs, values, and conditions of the local area [

17]. DIY efforts are particularly common in neighborhoods facing challenges such as a lack of affordable housing or recovering from natural disasters. As community-driven endeavors, they utilize urban design strategies to tackle social inequalities and foster inclusive, resilient neighborhoods that prioritize livability for all residents.

DIY practices offer numerous advantages to communities, including the ability to address issues of social inequality and exclusion, fostering more inclusive, resilient, and livable cities and neighborhoods. Empowering people to actively create, design, and shape their built environment, these practices provide individuals and communities with a sense of ownership and agency over their living spaces. They are adaptable to various cultures worldwide and are often undertaken by those seeking to take control of their surroundings in ways that reflect their needs, preferences, and values. DIY initiatives can emerge in response to various challenges, such as a lack of affordable housing or natural disasters.

Moreover, DIY practices have a unifying effect, bringing people together from diverse backgrounds and interests to collaborate on construction projects, share skills and knowledge, and forge social connections that strengthen community bonds. The inclusion of individuals with different skills expands the possibilities of these practices, enabling them to address environmental concerns and promote sustainability. DIY fosters experimentation, creativity, and innovation by encouraging the exploration of new materials, construction techniques, and urban design approaches. Projects of varying sizes offer opportunities for novel and inventive approaches to building and community development.

The first case study explored by students Edgar Montejano and Elias Hernandez is Community First Village, located in Austin, Texas, which is a non-profit organization dedicated to addressing homelessness by providing affordable housing and supportive communities [

18]. The village, spanning 51 acres (about twice the area of Chicago’s Millennium Park), is renowned for its comprehensive master plan aimed at transitioning homeless individuals into permanent housing [

19]. Divided into two phases, the completed first phase includes various amenities for over two hundred residents, with diverse housing options such as donated or locally built tiny homes. Central to the village’s ethos is community development, with numerous programs and amenities designed to engage residents and foster a sense of belonging. One prominent feature is the Genesis Garden, a community garden symbolizing rediscovery of purpose and establishment of roots in a new home. This garden not only provides organic produce but also serves as a collaborative space where residents work together, fostering relationships and a sense of achievement.

The village’s innovative townhomes exemplify sustainable design principles, emphasizing low-maintenance materials, energy efficiency, and careful site selection. Utilizing techniques like the “stack effect” ventilation system, homes are designed to maximize comfort while minimizing energy consumption. Local, sustainably sourced materials such as Silver Top Ash cladding further reduce environmental impact and embody the community’s commitment to sustainability. In addition to physical infrastructure, DIY projects like urban agriculture initiatives play a crucial role in community building and sustainability efforts. By transforming underutilized urban spaces into productive gardens, these projects empower residents to actively participate in creating green spaces and fostering social connections. Modular designs offer flexibility and adaptability, encouraging creativity and innovation while promoting community engagement. Furthermore, innovative projects like the VR urban SMS slingshot project demonstrate how technology can facilitate participatory urban design processes [

20]. By allowing individuals to contribute their own designs for public spaces using virtual reality and SMS messaging, this project empowers residents to reimagine their urban environment and actively shape their communities (

Figure 5) [

21].

6. Environmental Justice in West Virginia, Houston, and Amsterdam

The village’s innovative townhomes exemplify sustainable design principles, emphasizing low-maintenance materials, energy efficiency, and careful site selection. Utilizing techniques like the “stack effect” ventilation system, homes are designed to maximize comfort while minimizing energy consumption. Local, sustainably sourced materials such as Silver Top Ash cladding further reduce environmental impact and embody the community’s commitment to sustainability. In addition to physical infrastructure, DIY projects like urban agriculture initiatives play a crucial role in community building and sustainability efforts. By transforming underutilized urban spaces into productive gardens, these projects empower residents to actively participate in creating green spaces and fostering social connections. Modular designs offer flexibility and adaptability, encouraging creativity and innovation while promoting community engagement. Furthermore, innovative projects like the VR urban SMS slingshot project demonstrate how technology can facilitate participatory urban design processes [

22]. By allowing individuals to contribute their own designs for public spaces using virtual reality and SMS messaging, this project empowers residents to reimagine their urban environment and actively shape their communities.

Engaging in DIY practices can cultivate a sense of togetherness among individuals by providing opportunities for collaboration, skill sharing, and creativity (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). These practices can be tailored to fit diverse cultural backgrounds and interests, fostering social bonds, and promoting sustainable living practices. Overall, DIY initiatives contribute to the resilience and livability of communities while empowering individuals to take ownership of their built environment.

Student posters were created using Photoshop, utilizing images that best represent each case study and emphasize the impact of DIY practices on the community. These practices, being community-based, serve as effective means to improve the urban environment while fostering a sense of community among residents. For instance, the Community First Village poster highlights the concept of community gardens featuring live poultry, showcasing their proximity to residential areas. This resonates with Elias and Edgar as they have encountered similar living conditions in Mexico, where urban design incorporates elements like live poultry and locally grown produce to foster community cohesion. The parallels between these projects underscore the universality of DIY practices in enhancing urban living spaces and promoting community engagement.

DIY practices can foster sustainability, affordability, innovation, and community cohesion, empowering individuals and communities to actively shape their living environments (

Figure 8). Through DIY initiatives, communities flourish and thrive, enhancing their quality of life and revitalizing neglected or underdeveloped areas.

6.1. West Virginia, USA

West Virginia presents a unique case in terms of environmental justice, juxtaposed with its breathtaking landscapes is the extensive exploitation of natural resources, particularly coal, gas, and oil. While the state is rich in resources, its residents have not historically enjoyed significant wealth. Coal mining, a traditional industry in West Virginia, has posed considerable risks to miners’ health and safety due to cave-ins, heavy machinery use, and exposure to toxic air filled with coal particles [

22]. As coal usage declines due to its environmental impact, the state faces economic challenges. Moreover, environmental degradation persists, with runoff from coal mines polluting water sources and ongoing damage from natural gas and oil extraction activities (

Figure 9).

A significant portion of West Virginia’s population resides near these extraction sites, enduring the environmental consequences, including water and air pollution [

18]. Despite the importance of energy production for global needs, the residents of West Virginia bear the brunt of its negative effects. They contend with health hazards and environmental damage while providing resources essential for sustaining modern life.

6.2. Houston, Texas

In June 2022, the Department of Justice initiated an environmental justice investigation into allegations of illegal dumping in Black and Latino neighborhoods in the City of Houston. Illegal dumping, defined as the improper disposal of waste outside designated sites, poses significant public health risks and compromises the safety of residents near dumpsites [

23]. The investigation was prompted by a complaint filed by Lone Star Legal Aid on behalf of the Trinity/Houston Gardens Neighborhood, alleging discriminatory practices by the city against minority neighborhoods in Northeast Houston. Residents reported instances of illegal dumping, including tires, furniture, and other items, which obstructed drainage ditches and exacerbated flooding issues during heavy rains [

23]. Despite residents’ complaints, the city allegedly failed to address the problem adequately, prompting the Department of Justice to launch an investigation through its Civil Rights Division and Office of Environmental Justice. The investigation aims to address discriminatory actions against communities of color and lower socioeconomic classes [

23]. This case highlights the disparity in access to a clean and unpolluted environment, even in developed countries. Achieving environmental justice requires equitable treatment across all communities, ensuring that the same level of care is extended to every area (

Figure 10).

6.3. Amsterdam, Netherlands

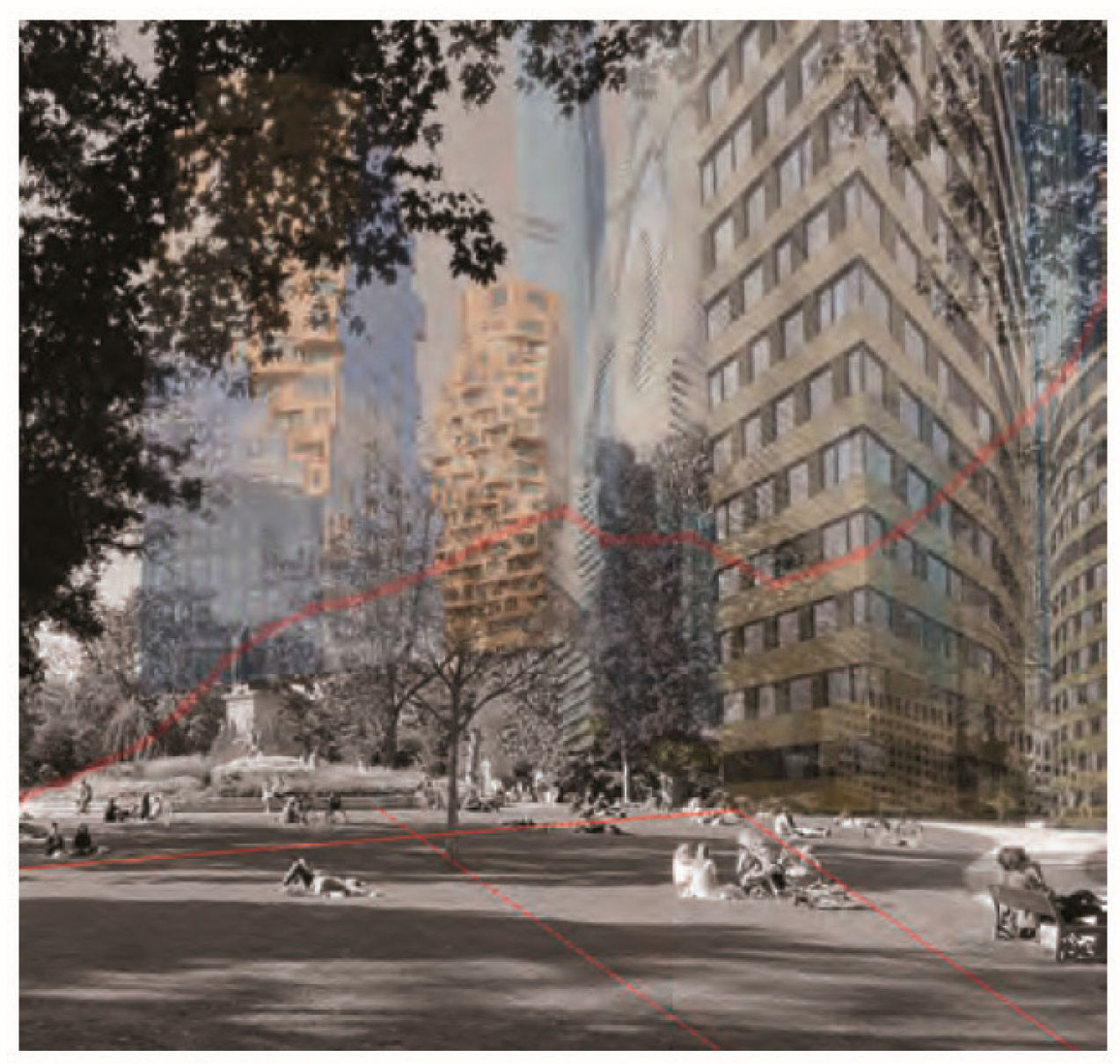

This case study examined the presence and quality of greenspaces in residential areas across various neighborhoods with different socioeconomic statuses, focusing particularly on dense urban cities like Amsterdam, Netherlands [

24]. Using data from the Statistics Netherlands database in 2012, neighborhoods were categorized based on indicators such as the percentage of households with low and high annual incomes, as well as average residential property values [

25].

In Amsterdam, this study assessed the quality of greenspaces by evaluating the ratio of greenspace available to the anticipated number of visitors and the scenic beauty of these areas. Mapping was conducted to identify the capacity for recreational walks in natural environments per neighborhood centroid. The findings revealed consistent socioeconomic disparities in the greenness of neighborhoods, regardless of the evaluation criteria used. These disparities underscore the importance of addressing environmental justice issues in greenspace management, particularly in densely populated urban areas. Accessible greenspaces play a crucial role in promoting the health and well-being of residents and communities, making it a matter of public health and safety (

Figure 11).

As urban populations continue to grow and cities densify, it is essential to revisit and adjust the standards for greenspace provision. Environmental justice should not only focus on cleaning up polluted areas and protecting the environment but also ensuring equitable access to greenspaces for all individuals. As cities evolve and expand, prioritizing equitable access to greenspaces becomes increasingly vital.

6.4. Thessaloniki, Greece

A city can be unjust in various ways, including limited access to essential services such as grocery stores, clinics, and educational facilities. This injustice often stems from unequal access to transportation options. The concept of a “15 min city” aims to address this by ensuring that citizens can reach most services and facilities within a 15 min walk or bike ride. A survey conducted in Thessaloniki, Greece, examined residents’ willingness to financially support infrastructure improvements to metro stations. However, the analysis revealed disparities in the distribution of these facilities, with some residents lacking access to essential services and amenities near metro stations. This lack of available spaces diminishes residents’ willingness to support infrastructure changes. Equitable distribution of services, including public transportation options like metro stations, as well as safe walking and cycling infrastructure, is crucial for achieving spatial justice in cities (

Figure 12).

In the poster creation process, students Georgia and Luke aimed to clearly identify each instance of environmental injustice by highlighting the actions and locations involved. Luke and Georgia intentionally included multiple case studies from various locations worldwide to underscore the prevalence of environmental injustice globally. These posters were crafted using Photoshop and carefully selected images depicting the specific actions and locations relevant to each case. By layering and juxtaposing multiple scenes, the posters were designed to engage viewers effectively. Each poster addresses a distinct aspect of environmental injustice. They do not offer idealized solutions but rather portray the harsh reality of issues such as illegal dumping, neighborhood disparities, and environmental harm resulting from unsafe development practices. Environmental justice is a universal issue that affects everyone. Whether it is the Bhalia Pipeline case in Memphis, highlighting the careless actions of corporations, or the situation in Houston, showcasing illegal dumping in minority neighborhoods, these actions have significant consequences. In many cases of injustice, activism emerges as a response to rectify the situation and protect both the environment and individuals’ resources. It is our responsibility to educate individuals about their rights to an environment that fosters physical and mental well-being, connecting each case study with the broader topics discussed in class.

7. Gender Justice in the United States and Iran

For generations, the architectural field has been predominantly shaped by the male gaze, resulting in designs that often reflect a masculine perspective and fail to consider the diverse experiences and viewpoints of women and marginalized groups [

26]. Activists, theorists, and feminist architects have spearheaded efforts to promote a more inclusive approach to design and planning, recognizing the urgent need for change. Feminist architecture goes beyond just physical design aspects; it encompasses a broader critique of the social, cultural, and economic factors influencing the built environment. It interrogates gender norms that have influenced architectural practices, such as the perpetuation of gender stereotypes in architectural representations or the relegation of women to supportive roles. A critical aspect of feminist architecture involves examining women’s experiences within architectural spaces, including their safety, comfort, and sense of agency influenced by spatial design. This entails challenging the dominance of male-centric design principles that prioritize esthetics over functionality or disregard the specific needs of diverse user groups [

26].

The following case studies were carried out by students Tahseen Anika and Karla Hernandez, to best exemplify how social, cultural, and economic issues affect the matter.

7.1. Abortion Rights Movement, USA

Abortion remains a contentious issue in the United States, with ongoing battles for reproductive rights and healthcare access, while pro-life proponents advocate for restrictions. The Texas Heartbeat Act, enacted in May 2021 [

27], has sparked criticism and legal challenges for potentially infringing on the abortion rights precedent established in Roe v. Wade. The Supreme Court’s decision not to block the law on September 1, 2021 has raised concerns about the potential loss of legal abortion access in numerous states, disproportionately affecting low-income women, women of color, and those in rural areas. Supporters of abortion rights argue that women should have the autonomy to make decisions about their bodies, emphasizing that limiting access to safe and legal abortion could result in severe health complications and curtail women’s opportunities. The recent implementation of stringent anti-abortion legislation in the United States has prompted widespread protests and demonstrations nationwide [

27].

In response to restrictive abortion regulations, architectural spaces can serve as platforms for reproductive justice advocacy. Community centers, parks, cultural institutions, and other architectural settings can be utilized by activists and organizations to host events, raise awareness, and mobilize support for reproductive rights. These venues can function as focal points for promoting advocacy, conducting outreach, and providing education on women’s reproductive health and abortion access (

Figure 13).

The poster regarding the abortion protest serves as a compelling tool in the ongoing discourse on reproductive rights in the U.S. It showcases photos of marches, rallies, and social media campaigns that aim to increase awareness of the issue and inspire supporters to act. The poster’s striking visuals, including vivid colors and eye-catching imagery, are reminiscent of the colors of the country’s flag. The collage Tahseen and Karla created incorporates photos from these protests. Overall, advocates for abortion rights believe that access to safe and legal abortion is essential for women’s autonomy, health, and well-being. They argue that women should be able to make their own decisions about their reproductive health without interference from the government or other outside forces.

7.2. Masha Amin Protest, Iran

For decades, Iranian women have been required by law to wear a hijab covering their hair in public, a mandate implemented after the Iranian Revolution in 1979 [

28]. While this law was somewhat relaxed during President Rouhani’s tenure, it was reinforced under President Raisi, leading to increasing discontent among the public. The death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman, on September 14, 2022, after being detained for not wearing a proper hijab and allegedly subjected to beatings and suffocation while in custody, sparked widespread protests. These demonstrations, known as the Mahsa Amini protests, were primarily aimed at ending mandatory hijab laws and advocating for greater political and social freedoms, including freedom of speech, expression, and an end to gender discrimination. The protests ignited a nationwide discussion about the role of women in Iranian society and inspired a surge of activism among women’s rights advocates. However, authorities responded with a violent crackdown, resulting in numerous deaths, injuries, and reports of human rights abuses and excessive force against protesters and detainees [

28]. Many individuals, including journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens, faced arrests and severe sentences for their involvement in the protests. The Iranian government’s handling of the protests and its efforts to suppress free speech and peaceful assembly have drawn criticism from international observers. In Iran, where architecture often reflects cultural values and societal norms, challenging these norms is essential to combatting violence against women and advancing gender equality. Architects can play a role in this by incorporating elements in their designs that challenge conventional gender roles and celebrate women’s achievements. By reshaping architectural representations, architects have the potential to influence cultural perceptions of women and violence, contributing to broader social change.

The poster serves as a poignant symbol of the women’s rights movement in Iran, showcasing compelling artwork that embodies the essence of the protests and sheds light on the challenges faced by women in the nation (

Figure 14). The striking depiction of a woman, her face partially obscured, conveys the ongoing battle for liberation and parity. With its bold imagery, the poster effectively raises awareness and galvanizes backing for the advancement of women’s rights in Iran.

7.3. Human Trafficking and Exploitation of Women, Amsterdam

Poverty and economic inequality are key drivers behind human trafficking and the exploitation of women in Amsterdam’s sex industry. Traffickers and pimps often use deceptive tactics, coercion, and violence to control and exploit women, particularly those from developing countries who lack access to education and economic opportunities. Many women are driven into prostitution by having their identification documents or passports withheld [

29].

The legalization of prostitution in Amsterdam has led to the implementation of regulations aimed at protecting sex workers, including licensing and healthcare services [

30]. However, critics argue that this approach merely perpetuates the objectification of women and fails to address the underlying causes of exploitation. Some believe that licensing legitimizes the exploitation of vulnerable women, and the government’s response does not adequately tackle issues of poverty or gender inequality [

30,

31]. Addressing human trafficking and exploitation in Amsterdam’s sex industry requires a comprehensive strategy that addresses root causes such as poverty, inequality, and gender-based violence. Raising awareness about the harms of prostitution and providing economic opportunities for women in developing countries are crucial steps. Additionally, promoting alternative approaches to addressing sexual needs is important. Furthermore, human trafficking has broader implications for the urban environment. Urban planning and zoning laws play a significant role in managing the spatial distribution of establishments that may facilitate human trafficking. Cities like Amsterdam can modify the physical environment to deter unlawful activities and create safer, more inclusive neighborhoods by implementing strict regulations and enforcement measures.

The poster is a powerful tool in raising awareness about human trafficking and exploitation of women in Amsterdam’s sex industry (

Figure 15). Through creative and thought-provoking images, it can help convey the message about the harms of prostitution and the need to address the root causes of trafficking and exploitation, including poverty and gender inequality. It can inspire action and create a dialog about how society can work towards a more equitable and just future for women in Amsterdam and around the world. The issue of human trafficking and exploitation of women in Amsterdam’s sex industry is complex and requires a multi-faceted approach. Women in prostitution are entitled to basic human rights, including health, safety, and dignity, and the protection of these rights requires addressing the root causes of exploitation and providing support services for those who choose to leave prostitution. Raising awareness about the harms of the sex industry and promoting alternative approaches to sexual desires and needs is also important.

8. Racial Justice

The pursuit of racial justice, as outlined by the American Civil Liberties Union, involves challenging and dismantling the systems of racial oppression that have historically targeted Black, Native American, and other marginalized communities in the United States [

31]. Each racial identity group experiences racial justice differently, with distinct challenges and injustices stemming from systems of white supremacy, colonialism, and patriarchy.

Racial discrimination remains pervasive worldwide, with ongoing struggles for racial equality [

32]. Instances of racial injustice, including mass shootings targeting minorities and gender disparities, continue to occur, fueled by supremacist ideologies. These injustices have led to widespread protests and calls for legal reforms to address discrimination and unequal treatment. Efforts to combat racial violence and discrimination have resulted in strengthened laws and enforcement measures against such acts [

33].

Across the nation, there is a growing movement of people participating in demonstrations for racial justice, expressing frustration with systemic oppression faced by people of color. Various institutions, including government, healthcare, media, education, and the criminal justice system, are scrutinized for their role in perpetuating racial inequality [

34]. The ongoing fight for racial justice aims to ensure equitable treatment and opportunities for all members of society, regardless of race, and to address systemic barriers to equality.

Society continues to adhere to outdated notions of race, leading to racial injustice and unfair treatment based on factors such as color, gender, religion, and culture. Immigration exacerbates these issues, as newcomers often face challenges and discrimination in their host countries.

Regina Lechuga, Maria Martinez, and Raymundo Retana focused on cities with high immigration rates where immigration is viewed as a problem, resulting in unfair treatment of newcomers. For instance, in Houston, Texas, a lawsuit filed by the Department of Justice in September 2016 alleged that a nightlife venue, previously known as Gaslamp, engaged in discriminatory practices by discouraging or denying admission to African American, Hispanic, and Asian-American customers [

35]. The owners violated Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin in public establishments like restaurants, hotels, and entertainment venues. As part of the settlement, the defendants agreed to cease discriminatory practices, adopt non-discriminatory admission criteria, establish a system for addressing discrimination complaints, and monitor employee behavior to ensure compliance with federal law [

35,

36].

Two of Regina, Maria, and Raymundo’s case studies take place in Los Angeles and Amsterdam. In Los Angeles, two men were apprehended in 2020 for assaulting five individuals inside a Turkish family-owned restaurant. During the attack, the perpetrators shouted ethnic slurs, threw chairs, and made death threats. This racially motivated violence stemmed from heightened tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with Turkey supporting the latter (

Figure 16).

While in Amsterdam, American singer Ari Lennox encountered racial discrimination while traveling in 2021. Lennox accused an airline staff member of discriminatory behavior and engaged in a dispute, resulting in police intervention. According to Lennox, she was arrested without being given the opportunity to explain her side of the situation. She asserted that the authorities showed bias by refusing to consider her account in their decision-making process [

37].

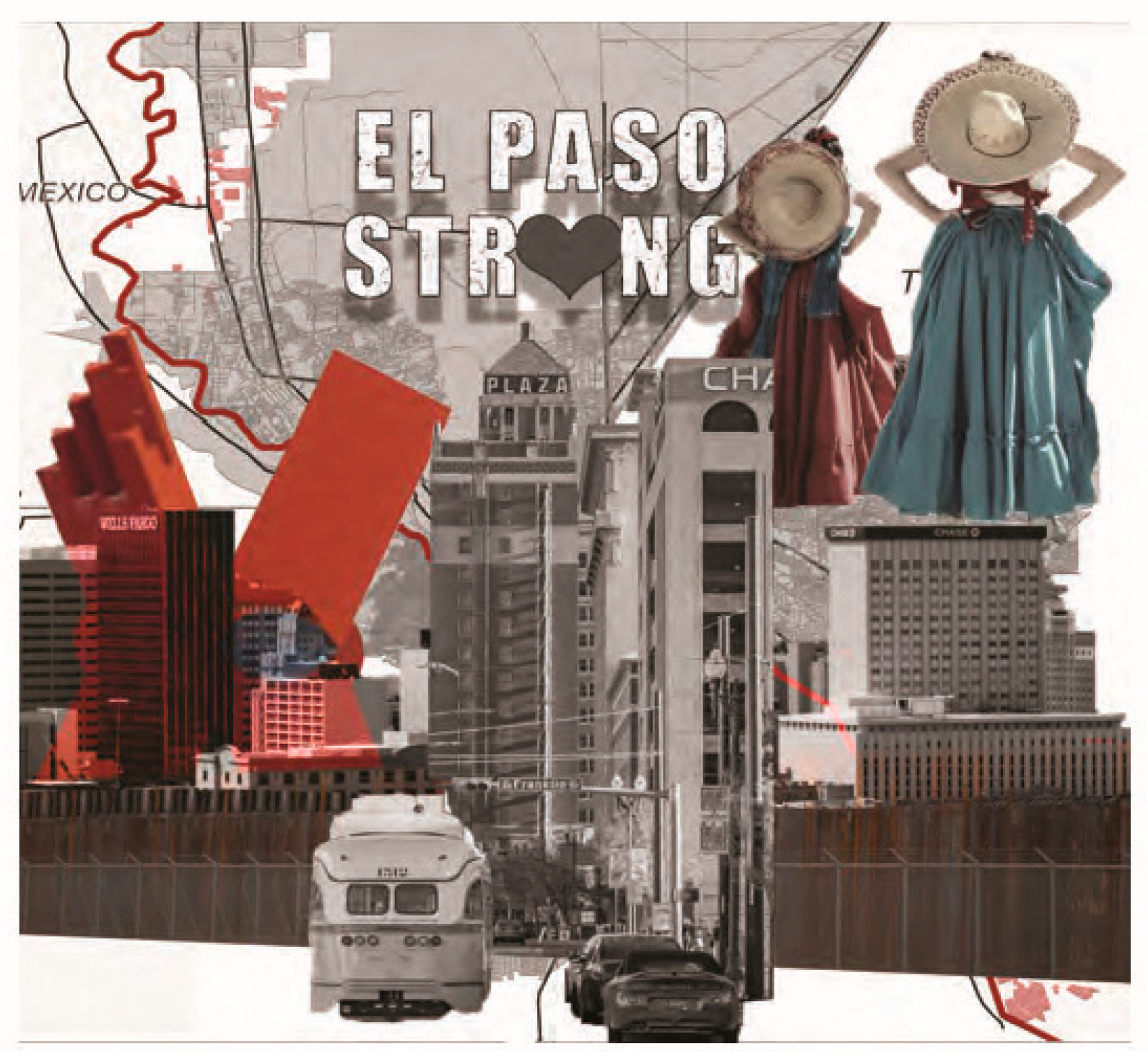

The final case study by Regina, Raymundo, and Maria occurred in El Paso, Texas, in September 2019, where Mexican citizens were targeted in a racial attack (

Figure 17). Patrick Wood Crusius, a 21-year-old white suspect, carried out the assault, opening fire with an AK-47 at the Cielo Vista Walmart. The attack resulted in the deaths of 23 people and left 22 others injured [

38,

39]. Crusius, who hailed from Dallas, Texas, chose to target the Walmart because it was frequented by Hispanic and Latino individuals, particularly those crossing over from Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Prior to the shooting, Crusius allegedly posted a “racist, anti-immigrant manifesto” on a website associated with white supremacy groups. In this manifesto, he expressed sentiments against interracial mixing and condemned what he perceived as a “Hispanic invasion of Texas”. Crusius claimed to be defending his country from what he saw as cultural and ethnic replacement caused by immigration. His language echoed that of certain political and media figures who characterized immigration from south of the border as an “invasion” and part of the “great replacement” of white people with people of color.

Racial injustice significantly affects people’s lives around the world, limiting their opportunities and jeopardizing their safety. Migration introduces new cultures and beliefs to communities, which some residents may perceive as threatening or distressing (

Figure 18 and

Figure 19). This perception often exacerbates the issue of racial injustice. Our case studies focus on communities with significant immigrant populations, where immigration is often viewed as problematic, leading to unfair treatment of new immigrants [

40].

The posters were crafted with a clear intention to convey the main ideas of the case studies through visually compelling collages. Each poster aimed to succinctly represent complex topics by merging images strategically, ensuring clarity and ease of understanding for viewers. Utilizing Photoshop, students Regina Lechuga, Maria Martinez, and Raymundo Retana carefully juxtaposed images to create artistic compositions that effectively communicate the essence of racial justice and its various manifestations in real-life events. These posters serve as visual aids that directly reflect the themes and ideas outlined in our manifestos, providing concrete examples of racial injustice and its impacts on individuals based on their race, skin color, or ethnicity (

Figure 18 and

Figure 19).

9. Discussions

In the area of Art Activism in Houston and San Diego, projects involved digital mapping and poster creation to visualize Art Activism’s role in fostering community identity [

40]. Murals and graffiti were analyzed for their impact on cultural cohesion, especially within Hispanic and Chicano communities. Findings indicated that Art Activism raised awareness and strengthened community bonds, offering a vibrant means for community members to engage with their cultural heritage and social identity [

41,

42].

For Tactical Urbanism in Burlington, Oak Cliff, and Jersey City, projects utilized short-term urban interventions like sidewalk extensions and bike lanes to enhance public space and social cohesion [

43]. Student evaluations revealed that these temporary, low-cost interventions significantly improved street safety and community engagement, demonstrating the potential of adaptable and budget-friendly urban designs to foster positive social interactions and make public spaces more inclusive [

44].

The DIY practice projects in Austin and Amsterdam focused on community-led initiatives in neighborhoods facing challenges such as homelessness and food insecurity. Through these DIY practices, residents were empowered to take ownership of their environments. Findings highlighted an increase in local agency and resilience, emphasizing the value of grassroots involvement in urban development and the potential of DIY methods to address urgent local needs [

45].

In the environmental justice projects conducted in West Virginia, Houston, and Amsterdam, students explored environmental inequities in marginalized communities affected by coal mining, illegal dumping, and limited green spaces. Spatial analysis revealed that residents in these areas faced disproportionate environmental health risks, underscoring the importance of equitable urban design in promoting health and well-being and addressing systemic environmental injustices.

Projects on gender justice in the United States and Iran examined architectural spaces as platforms for gender advocacy, including sites associated with the Abortion Rights Movement in the U.S. and the Mahsa Amini protests in Iran [

46]. These case studies revealed how spatial design can support gender advocacy and highlighted the need for gender-sensitive approaches in architecture, allowing for spaces that reflect diverse experiences and promote social equity.

In the racial justice projects, set in cities like Houston, Los Angeles, and El Paso, students explored racial discrimination in urban spaces by analyzing incidents and policies that have perpetuated racial inequalities. The results emphasized architecture’s role in either reinforcing or challenging racial biases, illustrating the impact of intentional design in creating inclusive urban environments that combat racial injustice.

Each of these projects demonstrated the potential of interdisciplinary urban interventions to promote social equity and strengthen community resilience. Collectively, they underscored the capacity of architectural education to address complex social issues through collaborative design and research, fostering a deeper understanding of the critical intersections between urban space, equity, and community engagement.

10. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to explore how interdisciplinary urban interventions in architectural education can address social justice issues. Key findings reveal that collaborative design and participatory research approaches, applied across diverse urban contexts, enhance students’ understanding of social justice themes such as environmental, racial, and gender equity. These findings underscore the value of integrating multi-scalar, interdisciplinary frameworks into architectural education, preparing students to tackle complex urban challenges with empathy and awareness.

The case studies, ranging from Art Activism to Tactical Urbanism, reveal the transformative power of integrating social justice considerations into architectural practice and education. For instance, the Art Activism projects in Houston and San Diego underscore the role of artistic expression in challenging societal norms and fostering a sense of community identity. Similarly, the Tactical Urbanism initiatives in Burlington, Oak Cliff, and Jersey City illustrate how small-scale interventions can lead to significant improvements in public spaces and social cohesion. Furthermore, the projects emphasize the need for a multi-scalar approach that addresses social justice issues at various levels, from individual buildings to entire neighborhoods and cities. The DIY practices in Austin and Amsterdam, for example, highlight the potential of community-led initiatives to create more livable and equitable urban environments. Additionally, the focus on environmental, gender, and racial justice in the case studies underscores the interconnectedness of social justice issues and the necessity of a holistic approach to urban design and planning.

The results align with current literature on the value of interdisciplinary approaches in social justice-oriented architectural education. This study demonstrates that when architecture students engage directly with community challenges, they gain a deeper understanding of complex urban issues and develop practical skills in collaborative problem-solving. Compared to traditional architectural education, the interdisciplinary, participatory approach used here provided students with a holistic view of urban design. For example, Tactical Urbanism projects reinforced the importance of low-cost, adaptable solutions, while environmental justice projects underscored the need for inclusive green space planning. In conclusion, the interdisciplinary and multi-scalar design and research models showcased in this paper provide valuable insights for architectural practice and education. They illustrate the importance of addressing social justice issues in the urban context and demonstrate the potential of collaborative and participatory approaches to create more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable cities. As we move forward, it is crucial to continue exploring and integrating these interdisciplinary approaches to address the complex challenges facing urban environments today.

This study’s implications suggest that policymakers and industry leaders could benefit from adopting similar collaborative approaches in urban design, emphasizing inclusivity and resilience in community planning. This model can inform policy decisions aimed at fostering equitable urban environments and encourage industry practices that prioritize social justice outcomes in the built environment.

Future research could expand on this framework by exploring its application in a broader range of urban contexts and conducting longitudinal studies to examine the long-term impact of these interventions. Such studies would further establish interdisciplinary urban interventions as an effective model for advancing social equity in architectural education and practice.