1. Introduction

As digital technology permeates every aspect of our daily lives, our perception and interaction with architectural spaces are undergoing significant transformation. Social media platforms, particularly Instagram, have emerged as powerful mediators between individuals and their built environments [

1], reshaping not only spatial perceptions but also temporal interactions with architecture [

2,

3]. Since its launch in 2010, Instagram has attracted over 1 billion active users, who share more than 100 million photos and videos daily [

4]. Its visually driven interface, featuring filters, hashtags, geotagging, and stories, makes it a prominent tool for visual storytelling and social interaction [

3,

5,

6]. Instagram not only redefines the presentation of architecture but also transforms the way users experience, interpret, and contextualize architectural spaces across different times and places [

7,

8]. This study focuses on the perceptual aspects of spatial experience and how digital media affects sensory and phenomenological engagement with architecture.

Instagram fosters communities based on shared interests, including architecture, creating networked spaces where past, present, and future converge [

2]. Users can follow architects, designers, and fellow enthusiasts globally, engaging in dialogues that transcend geographical and temporal boundaries [

9]. The platform enables virtual access to buildings and environments worldwide, collapsing spatial distances and altering traditional notions of proximity. This increased exposure to diverse architectural styles fosters a global conversation about design and cultural significance [

10,

11]. Moreover, features like archived stories and time-lapse videos [

12] allow users to document and revisit moments, creating a temporal layering that contributes to collective memory and identity formation within architectural spaces [

10,

13,

14]. However, the curated nature of Instagram often prioritizes visual aesthetics, potentially distorting deeper experiential qualities of architecture. Visually striking images can emphasize photogenic elements while overlooking the functional, historical, or social contexts of architectural spaces [

15]. This may lead to a focus on momentary appeal rather than the inherent temporal and spatial narratives of a building, raising questions about the depth of engagement users have with the architecture they consume online and how digital media reshapes these experiences.

Architects are increasingly designing with Instagram in mind, creating “Instagrammable” moments that capture attention and drive engagement. Iconic examples include interactive installations at the Color Factory or the immersive environments of TeamLab Borderless, both designed to be visually captivating and highly shareable on social media [

3,

7]. While this trend can boost public interest, it also raises concerns about the commodification of architectural spaces and the potential distortion of spatial and temporal experiences. Designing for social media may prioritize spectacle over substance, potentially undermining the functional and social responsibilities of architecture [

16,

17].

A phenomenological approach offers a valuable lens for exploring how Instagram mediates our embodied experiences of time and space. Phenomenology emphasizes lived experience and consciousness [

18,

19,

20], providing a framework to understand the interplay between perception, cognition, and environment [

21,

22]. Through this lens, we can examine how Instagram mediates users’ experiences, potentially altering their perceptions of presence, authenticity, continuity, and spatial relationships within architectural settings. Digital representations on Instagram can create familiarity with spaces users have never physically visited, influencing expectations and interpretations while disconnecting them from the temporal narratives of those spaces. The platform’s emphasis on visual content often leads to a disembodied experience, where multisensory aspects of architecture, such as the play of light throughout the day or the aging of materials, are overlooked [

23,

24,

25]. Recognizing these limitations is essential for fostering a more holistic understanding of the ways in which digital media influences our temporal and spatial interactions with the built environment.

This paper offers original insights at the intersection of phenomenology, architecture, and digital media, highlighting the significance of a phenomenological approach in addressing the challenges introduced by the mediatization of architecture. The research objectives are threefold: first, to analyze how Instagram’s features influence the presentation and perception of architectural spaces over time; second, to explore how Instagram mediates sensory and social experiences, merging physical and virtual realms; and third, to assess the implications of “Instagrammable” architecture on design practices and social contexts. Key questions guiding this inquiry include: How do Instagram’s features affect architectural perception and social interaction? What patterns emerge in user engagement with architectural content over time and across different spaces? How does Instagram shape architectural design, and what ethical implications arise from its influence? Understanding Instagram’s role in contemporary architecture is crucial for navigating the complexities of digital mediation and its effects on our perception of time and space. By examining the platform’s impact, we can identify both opportunities and challenges that inform the design of meaningful and socially responsive architectural spaces in a globally interconnected world.

2. Methods

Quantitative methods are rarely employed in star architecture research, as highlighted by Alaily-Mattar et al. [

26], with few exceptions [

27,

28]. Much of the literature on iconic architecture [

17,

29,

30], relies on personal observations, which, while insightful, can introduce subjective biases. This research seeks to advance the understanding of architectural perception by integrating both qualitative and quantitative digital methods. It follows a three-phase methodology to explore how architectural spaces are perceived and engaged with in the digital realm, particularly through Instagram (

Figure 1). The first phase consists of a comprehensive literature review that establishes a theoretical framework grounded in phenomenology and mediatization in architecture. Phenomenology emphasizes the embodied, sensory engagement with architectural spaces [

19,

23,

24], offering a foundation for understanding how architecture unfolds over time, beyond just visual perception. This framework is essential for analyzing the influence of Instagram on spatial and temporal perceptions, especially in an era where digital media frequently mediate architectural experiences. Mediatization, which refers to the growing influence of media on various aspects of life [

31], helps contextualize Instagram’s role in shaping how people perceive and interact with architectural spaces. The literature review also draws on studies of iconic or “star” architecture, exploring how buildings designed by renowned architects are portrayed and symbolized in popular media [

26,

32,

33].

The second phase focuses on selecting and analyzing Instagram data related to two iconic buildings: Tai Kwun in Hong Kong and Kunsthaus in Graz, Austria. These buildings were chosen for their contrasting geographical and cultural contexts, representing Asia and Europe, and their embodiment of star architecture [

34,

35]. Tai Kwun is an adaptive reuse project that transformed a colonial-era police compound into a cultural hub, blending historical preservation with modern design. Kunsthaus, with its futuristic biomorphic form, serves as a contemporary architectural landmark in Graz. Both buildings offer rich examples of how time manifests in architecture, through the historical preservation at Tai Kwun and the forward-looking design of Kunsthaus. Their active presence on Instagram provides an opportunity to study user engagement and how these iconic spaces are framed, shared, and interpreted in the digital realm. In this context, iconic architecture embodies temporal meanings reflecting a city’s past, present, and future [

36].

The third phase involves analyzing Instagram posts related to these case studies. The quantitative analysis focuses on user engagement metrics, such as likes, comments, hashtags, and shares, from 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2024 to evaluate interaction levels and post popularity. This analysis helps identify which posts or themes generate the most engagement, providing insights into how users digitally interact with these architectural spaces. Concurrently, the qualitative analysis involves both visiting the architectural sites in person and examining the Instagram data. The site visits provide a firsthand experience of the physical aspects of the architecture, enabling a deeper understanding of the spaces in their real-world context. This immersive approach captures sensory and spatial qualities that may be missing in digital representations. The analysis of Instagram posts focuses on elements like image filters, framing techniques, and captions, exploring how they shape user perceptions of the architecture. Moreover, this study addresses how digital platforms, by emphasizing visuality, can distort the perception of architecture, potentially overshadowing other sensory or interpretive dimensions [

19,

24] that are traditionally experienced through physical interaction with the environment [

31,

37,

38].

3. Architectural Phenomenology

Architectural phenomenology is a philosophical approach that emphasizes the profound connection between human experience, perception, and the spaces we inhabit [

25,

39,

40]. It offers a framework for examining how digital platforms like Instagram influence sensory experiences, particularly in a modern context where digital imagery plays an increasingly significant role in shaping public perceptions of architecture. Emerging in the latter half of the 20th century, architectural phenomenology challenges traditional approaches that prioritize functionality or aesthetics alone. Instead, it advocates for designs that resonate with human existence, encouraging a deeper, more meaningful engagement with the built environment over time. In an era dominated by digital media, the principles of phenomenology provide a valuable counterbalance. This approach encourages architects to consider not only the physical form of buildings but also the intangible qualities of space, how it feels, evokes memories, and contributes to our sense of place [

13,

14]. Focusing on perceptual experience allows us to understand how digital media reshapes our engagement with space and time.

Architectural phenomenology also addresses broader environmental and social challenges [

41,

42,

43]. Sustainable design, for instance, goes beyond energy efficiency and material choice. It involves creating environments that are resilient, adaptable, and deeply connected to their inhabitants throughout time. By incorporating phenomenological principles, architects can design spaces that foster a sense of belonging, support well-being, and encourage long-term sustainability [

40,

44,

45]. This approach also enhances the cultural and historical dimensions of architecture, emphasizing the importance of place, memory, and cultural continuity [

14]. It ensures that new developments contribute meaningfully to the ongoing narrative of a location, not merely functioning as additions to the urban landscape [

46,

47].

Table 1 summarizes the contributions of key theorists and phenomenologists, highlighting their influence on the development and application of architectural phenomenology.

3.1. Foundations of Architectural Phenomenology: Consciousness, Perception, and Being

The philosophical roots of architectural phenomenology can be traced back to Edmund Husserl, who introduced the concept of “transcendental aesthetic” in the early 20th century, exploring how consciousness shapes our perception of the world [

20,

51,

52]. For Husserl, perception is central to how we engage with and interpret our surroundings [

51,

61]. His idea of phenomenological reduction, a method of stripping away preconceived notions to uncover the essence of experience, provides a framework for architects to design spaces that prioritize the pure experience of space and time over mere functionality or aesthetics.

Martin Heidegger, a student of Husserl, expanded these ideas in his seminal work Being and Time (1927), introducing the concept of “being-in-the-world”. Heidegger emphasized that human existence is fundamentally interconnected with the spaces they inhabit [

53], challenging the traditional separation between individuals and their environment. He argued that architecture should reflect this interconnectedness, creating spaces that allow for genuine dwelling, resonate with lived experiences, and foster a sense of belonging [

46,

54].

Maurice Merleau-Ponty further developed these ideas by focusing on the relationship between the body, perception, and temporality. In Phenomenology of Perception (1945), Merleau-Ponty argued that our bodily experiences are deeply intertwined with our perception of space and time [

21]. He emphasized the importance of designing environments that engage all senses, creating spaces that are not just visually appealing but also felt and experienced through the body [

62]. Merleau-Ponty suggested that our experience of the present is always informed by the past, making temporality a key aspect of perception.

3.2. Human Interaction with Space: Embodiment, Social Context, and Technological Mediation

As architectural phenomenology evolved, theorists began to explore how human interaction with space is shaped by the body, social contexts, and technological advancements. Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s emphasis on embodied perception underscores the importance of designing architecture with the human body in mind [

22,

55]. He argued that spaces are not passively observed but are actively experienced through movements and sensory interactions, encouraging architects to design environments that respond to the physical and sensory needs of their inhabitants.

Alfred Schutz expanded on this by introducing social phenomenology, adding a social dimension to our understanding of space. Schutz argued that architectural spaces are not merely physical environments; they are also shaped by human interactions and shared meanings that occur within them over time [

43,

60,

63]. This perspective suggests that architecture should facilitate social interaction, reflect cultural and historical values, and support community life over time. By incorporating these social and temporal dimensions, architects can create spaces that are functional and socially meaningful, acknowledging the passage of time and its impact on human experience.

Marshall McLuhan, known for his media theory, examined how technology mediates our interaction with space [

57]. In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), McLuhan proposed that media technologies extend human senses and alter our perception of space and time [

56,

57]. He suggested that buildings, like other forms of media, shape our sensory experiences and interactions with the world. In the digital age, social media images may present an idealized or altered version of a space, affecting our expectations and sensory engagement. McLuhan’s ideas challenge architects to consider how digital media can either enhance or distort the authenticity of architectural experiences, raising questions about how technology impacts the perception of space and time.

3.3. The Poetics of Place and Multi-Sensory Experience in Architecture

Architectural phenomenology highlights the significance of place and multi-sensory engagement in creating meaningful spatial experiences over time. Christian Norberg-Schulz introduced the concept of “genius loci”, or the spirit of a place, emphasizing that architecture should resonate with the unique characteristics of its environment [

49], fostering a strong sense of place and belonging [

48,

49]. Juhani Pallasmaa expanded on Norberg-Schulz’s ideas by emphasizing the importance of multi-sensory engagement in architecture. In The Eyes of the Skin (1996), he critiqued the dominance of visual aesthetics in modern architecture and advocated for designs that engage all the senses, such as sight, touch, hearing, and smell [

23,

24,

58,

64]. Pallasmaa argued that tactile materials and sensory-driven design evoke moods and emotional responses that create deeper connections to space.

Steven Holl, a contemporary architect, supported this viewpoint by emphasizing that the essence of a place is shaped by multi-sensory interactions and memory [

19]. In his book Intertwining (1996), he introduced the concept of “phenomenal transparency”, layering spaces and materials to create depth and complexity in architectural experiences [

44,

45]. His designs often focus on light, materiality, and the sensory journey of moving through space, aiming to evoke a profound emotional and experiential response. Holl believes that engaging multiple senses allows architecture to create deeper, more meaningful connections with its users, making each encounter with a space distinct and memorable. Alberto Pérez-Gómez further enriched the field by bringing a hermeneutic and poetic dimension to architectural phenomenology. In his book Built upon Love (2006), he argued that architecture should not only meet contemporary functional needs but also engage with cultural memory and express the poetic dimensions of human existence [

65]. Pérez-Gómez emphasized that historical and cultural narratives should inform design, ensuring that architecture resonates with both the past and present.

In the context of digital media, these principles highlight the importance of maintaining the multisensory richness and temporal continuity of architectural experiences. While digital technologies offer new design possibilities and forms of engagement, they can also lead to a disconnection from the tactile and temporal aspects of space. The immediacy and visual bias of digital media may overshadow the slower, more immersive experiences that contribute to a deep sense of place and time.

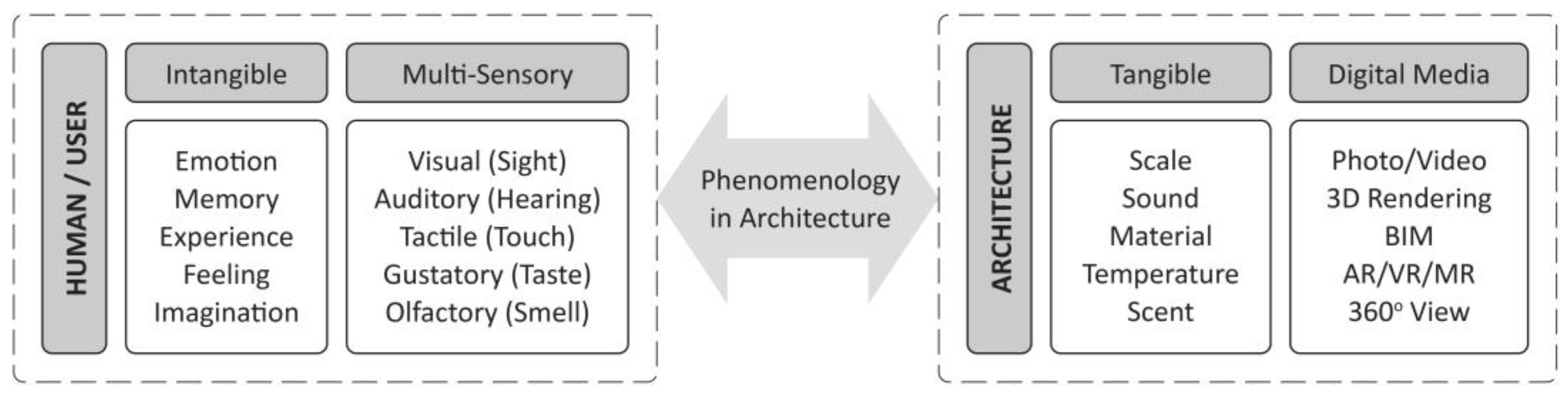

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between humans and architecture through the lens of phenomenology, highlighting the interaction between tangible, intangible, multi-sensory experiences, and digital media elements in architectural design.

4. Mediatization of Architecture

Mediatization in architecture refers to how media, particularly digital platforms, transform the design, presentation, and experience of architectural spaces [

38]. The relationship between architecture and media has evolved from traditional sketches and blueprints to digital photography and social media [

66]. This transformation has significantly impacted the ways in which architects and the public perceive and interact with buildings. Platforms like Instagram have accelerated this process, making buildings instantly accessible to global audiences [

3]. While this increased visibility offers new opportunities for engagement, it can also reduce the architectural experience to brief, visually oriented encounters that neglect deeper, more immersive aspects of design.

With the rise of photography in the early 20th century, media began playing a significant role in architecture. Beatriz Colomina (2000) observed that photography shifted architectural focus from construction sites to magazines and journals [

67], meaning architecture was defined not only by its physical presence but also by the images representing it. In the digital age, this dynamic has intensified. Kenneth Frampton (1986) argued that photography, and now digital platforms, can reduce architecture to superficial images that lack the depth of embodied and temporal interaction [

68]. This is particularly evident in iconic architecture, where buildings are designed with media consumption in mind, often prioritizing aesthetics over functionality or user experience. Thomas Elsaesser (2018) noted that many modern buildings cater more to the camera’s eye than to the lived experience of their users [

69], leading to what Simone Brott (2019) describes as a “digital paradigm”, where images of iconic buildings circulate widely on social media, overshadowing the temporal and spatial realities [

70].

Mediatization enables the rapid dissemination of architectural images, blending a building’s past, present, and future into a single visual narrative. For instance, Plaza and Haarich (2015) argue that the global success of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, designed by Frank Gehry, was largely driven by its online presence and the fame of its architect, which amplified its visual appeal beyond the physical structure [

71]. The building became a symbol of Bilbao’s identity and future aspirations through its digital representations [

28,

72]. While mediatization can extend the reach of iconic architecture, it risks oversimplifying the complex temporal layers that contribute to a building’s full experience. Architectural spaces are dynamic and evolve over time, interacting with history, culture, and memory [

14,

70,

73]. Social media’s emphasis on visual representation compresses these temporal layers, reducing architecture to a momentary spectacle rather than a lived, evolving space.

As digital platforms increasingly dominate the architectural landscape, architecture becomes inseparable from its media representation. Kester Rattenbury (2002) suggests that buildings are now often designed to align with their digital portrayals [

74]. Social media has revolutionized architectural communication, allowing architects to share their work with a global audience instantly [

9,

32]. While this fosters greater interaction and shapes public perception, it often prioritizes aesthetic appeal over other sensory or spatial qualities, potentially oversimplifying the architectural experience. This section examines the impact of social media on iconic architecture, the role of Instagram as a “third space”, and the ethical challenges posed by architecture’s growing dependence on digital media.

4.1. Iconic Star Architecture

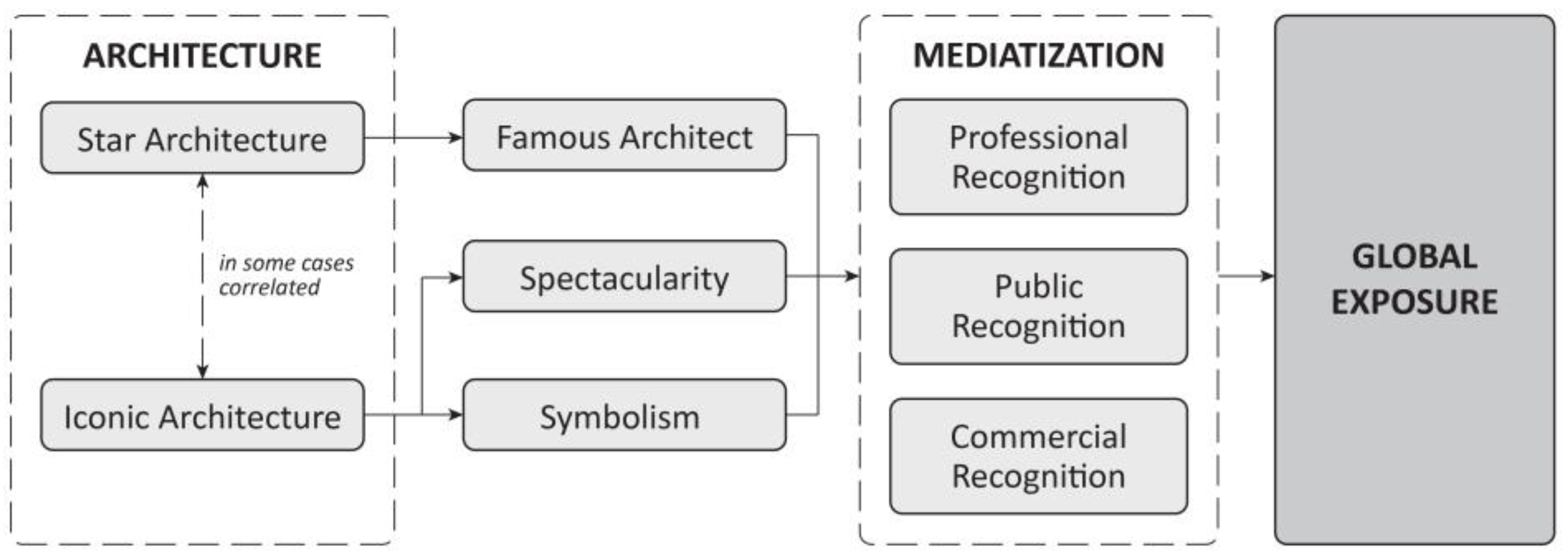

Digital technologies increasingly influence the relationship between architecture and time. Scholars like Plaza (2006), Nastasi (2020), and Ponzini (2011) identify the rise of star and iconic architecture as part of this shift [

6,

75,

76]. The term “star” emphasizes the recognition status of an architectural project, driven either by the architect’s reputation or the iconic status of the building itself (

Figure 3). While the architect’s fame, bolstered by media exposure, plays a crucial role in elevating projects to iconic status, it is not the sole factor. Multiple actors in the development process, including institutions and media, contribute to a project’s iconic stature [

77]. Architects are often selected based on indicators such as prestigious prizes, media presence, and publication [

78]. The Pritzker architecture prize, for instance, is a key measure of professional recognition [

79,

80], and media coverage helps shape the global influence of these architects.

Two key factors contribute to the iconicity of an architectural project: spectacularity and symbolism [

35]. Spectacularity refers to the visual distinctiveness that makes a building stand out from its surroundings, often turning it into a recognizable urban landmark. Symbolism, on the other hand, suggests that architecture conveys meanings beyond its physical form, representing cultural, historical, or urban ideas. Charles Jencks (2005) introduced the idea of “enigmatic signifiers”, noting that iconic buildings often allow for multiple interpretations and can serve as symbols of cities or cultural narratives [

29]. Both spectacularity and symbolism are closely tied to the visual prominence of architecture, a trend that has been intensified by digital media, where images of buildings circulate widely, often becoming as significant as the physical structures themselves.

Digital media have extended the temporal reach of architectural spaces far beyond their physical existence. Through online images, buildings are not only shared globally but also experienced, remembered, and revisited over time, creating a lasting digital presence that can outlive their physical context [

16,

17]. This phenomenon alters how buildings are perceived over time, allowing them to exist in collective memory long after their creation. Brott (2020) critiques this digital abstraction, arguing that media representations often shape the temporal experience of architecture, influencing how people perceive and engage with iconic buildings [

70]. These digital representations, widely circulated on social networks, can establish a predefined narrative of iconicity that may dominate public perception. In this way, social media reinforces pre-existing perceptions of iconic architecture, much like tourist guides or promotional materials [

81]. However, the experience of iconic architecture is not solely shaped by digital representations. Visitors engage with these buildings in real time, bringing their own perspectives through sightseeing, daily use, or personal memories. This raises important questions about the temporal relationship between iconic architecture and its visitors: Does a building’s iconicity impose a fixed, uniform experience over time? Or can the widespread dissemination of images and memories on social media offer alternative ways of engaging with these buildings, disrupting traditional narratives of experience?

4.2. Instagram as a Third Space

Yi-Fu Tuan (1977) distinguished between “space” and “place”, suggesting that space becomes a place when humans attach meaning to it [

82]. While space is often considered neutral or abstract, place is socially constructed and imbued with meaning. Doreen Massey (1994) emphasized that space is dynamic, shaped by human experiences and social relations [

83]. Building on these ideas, Henri Lefebvre and Edward Soja questioned the binary between real and imagined spaces. Soja’s concept of “third space” blends the real (first space) and imagined (second space), highlighting the role of communities in experiencing them [

84]. This third space is where the physical and digital realms intersect, allowing new ways of engaging with and interpreting space. As digital platforms like Instagram become integral to our lives, they emerge as a contemporary third space, enabling users to engage with architecture beyond physical limitations. Instagram facilitates virtual “place-making”, giving users a sense of connection and belonging to spaces they may never physically visit. Sarah Pink (2008) argues that place-making involves embodied and imaginative practices, which Instagram enables through its visual and social features [

85].

Today, the places and spaces where architecture is encountered have become diverse, ranging from traditional physical sites to ephemeral, informal, and intangible digital spaces. These digital spaces, accessed via screens and mobile devices, allow users to engage with architecture in ways that transcend physical movement [

86]. Architecture is no longer confined to buildings or physical locations; it is encountered through virtual interactions, geotagged images, hashtags, and augmented reality (AR) filters. Instagram, as a third space, merges the physical and digital, reshaping how we experience and perceive architecture in an evolving cultural landscape.

4.2.1. Architectural Perception Through Instagram Features

Architects aim to create aesthetic experiences, with the visual element being fundamental [

87]. However, as Burnham (1994) observes, the visual experience of architecture evolves, and Instagram has significantly contributed to this evolution [

88]. The platform extends architectural perception beyond a single visit, enabling users to share images that can be revisited and reinterpreted across different contexts. Instagram’s features, such as feeds, stories, highlights, and reels, influence how architecture is documented and shared (

Table 2). Feeds allow users to upload curated images of architectural spaces that remain indefinitely on their profiles, creating a permanent digital presence accessible globally [

10,

15]. Stories offer transient engagement, disappearing after 24 h, but highlights can preserve them, allowing for extended interactions that can be revisited at any time. This accessibility enables people to reflect on the experience long after the visit, altering architectural perception in the digital age.

Photo filters, introduced when Instagram launched in 2010, allow users to modify the color, contrast, and mood of images, transforming architectural perception. Borges-Rey (2017) argues that using vintage-style filters, for instance, indicates a desire to move away from conventions of realism, symbolizing a longing for “fabricated nostalgia” [

3] where architectural spaces evoke a sense of the past or a romanticized reality [

91]. While such filters can enhance a building’s visual appeal, they may also distort the public’s understanding of the space, altering its authentic representation [

7].

In August 2019, Instagram introduced augmented reality (AR) filters through Facebook’s Spark AR platform, enabling users to superimpose digital elements onto real-world environments. AR filters allow creative manipulation of architectural spaces by altering colors, textures, and adding digital components. As Wagiri (2024) explains, AR filters blend real and virtual worlds, fostering dynamic interactions with architecture [

92]. These AR filters are shareable, allowing users to distribute both their modified images and the filters themselves, promoting widespread use and contributing to a new layer of digital engagement. While AR filters offer exciting ways to personalize and reshape architectural perception, they also raise concerns about authenticity. These digital alterations can potentially overshadow the architect’s original design and intent.

4.2.2. Place-Making Through Geotagging and Hashtags

Instagram’s geotagging and hashtag features have redefined the concept of place-making by allowing users to engage with both the physical and digital realms of spaces. Sarah Pink (2008) highlights that place-making involves “embodied and imaginative practices” as well as social relationships that foster a sense of belonging to specific locations [

85]. Through these features, Instagram connects people, encouraging them to explore, share, and contribute to the experience of architectural spaces, offering new ways to perceive and understand places [

96].

Geotagging enables Instagram users to tag images with the exact physical location of a site, leaving a digital footprint of architectural spaces. Other users can explore these locations virtually, viewing collections of posts from the same site. This shared digital environment broadens access to architecture, offering diverse perspectives on a single location. Frith and Kalin (2016) point out that geotagging helps define places as dynamic, evolving entities that can be revisited and explored anytime, from anywhere [

89]. In this sense, geotagging functions as a digital “third space”, akin to Ray Oldenburg’s (1989) concept of the “great good place”, where people gather outside of work and home for interaction and transformation [

90]. On Instagram, geotagging creates a virtual third space where users engage in discussions and experiences related to architecture, transcending physical boundaries [

7]. This reshapes how architecture is perceived, fostering a sense of connection and presence even for users who are not physically at the location.

Hashtags, on the other hand, play a key role in organizing and categorizing architectural images. By using hashtags such as #architecture or #modernarchitecture, users can group their images with others of similar themes or styles, creating virtual communities centered on shared architectural interests or trends [

10,

97]. This reflects Pink’s (2008) concept of place-making as a social and imaginative process, as hashtags facilitate collective interpretation and discussion through shared digital spaces [

85]. Hashtags enhance the visibility of architectural projects, increasing user engagement and enabling the discovery of new designs and places that might otherwise go unnoticed [

2]. They shape how users find and interact with architectural content, fostering a participatory culture where users contribute to the evolving narrative around architectural spaces. For example, liking a post with a specific hashtag or tagging a photo with #brutalistarchitecture links the post to a larger conversation about brutalism, positioning the building within a specific architectural context and influencing public perception of styles and trends.

While geotagging and hashtags contribute positively to digital place-making, they also raise concerns about the commodification of architectural spaces. As Borges-Rey (2017) notes, platforms like Instagram often shift away from “conventions of realism” and objectivity, resulting in curated, stylized representations that may not fully reflect a building’s true qualities [

91]. Popular hashtags like #minimalism or #architectureporn tend to emphasize surface-level beauty, reducing architecture to its most photogenic aspects [

3,

98]. The overuse of certain hashtags can lead to homogenized presentations, overshadowing the cultural, historical, and functional dimensions that truly define a building. Mitchell’s concept of the “pictorial turn” is particularly relevant in this context, as it explores how images shape our perception of reality [

95]. On Instagram, algorithms often favor specific visual styles, shaping how architectural spaces are presented and perceived by the public. Over time, this can narrow the range of interpretations, making visual images the primary way people engage with architecture. This “pictorial turn” risks becoming a “pictorial trap”, where the complexity and richness of architectural spaces are reduced to easily consumable visuals, disconnecting viewers from the full, lived experience of these environments.

4.3. Ethical Challenges in Digitally Mediated Architecture

The digital mediation of architecture through Instagram has transformed how architectural spaces are perceived and engaged with, raising several ethical challenges. One major concern is the potential for superficial engagement due to social media’s emphasis on visual appeal. Sherry Turkle (2015) notes that the highly curated nature of social media leads to an emphasis on appearances over meaningful interactions [

37]. In architecture, this results in a focus on aesthetics over functionality or contextual relevance [

31,

38]. Architects may feel pressured to design spaces that photograph well on social media, which could compromise essential design elements that enhance the lived experience.

The notion of authenticity in architecture is also being transformed by digital platforms that encourage experimentation and speculative representations. This shift often detaches architectural aesthetics from real-world experiences, focusing on visually appealing, sometimes fantastical interpretations designed to resonate with online audiences. Tools like Instagram’s Spark AR enable users to modify or enhance architectural spaces, creating representations that may significantly diverge from their physical reality. While these tools offer creative possibilities, they can obscure the practical, functional, and historical qualities of the spaces depicted. Such practices challenge the authenticity of architectural representations, raising ethical questions about how architecture is portrayed and understood in the digital sphere. Moreover, the rise of AI-generated images further complicates this issue, as the distinction between real architectural photographs and artificial ones becomes increasingly blurred, making it difficult to discern authenticity.

The debate around Instagram’s influence on architecture often contrasts physical presence with digital interaction. Some critics argue that the concepts of “place” and “being present” are diminished when architectural experiences are mediated through digital platforms. However, Nathan Jurgenson (2011) challenges this perspective by criticizing “digital dualism” and emphasizing that the physical and digital realms are increasingly intertwined [

66]. Both physical and digital experiences influence how architecture is perceived and engaged with, suggesting the need for a nuanced understanding.

Moreover, the digital transformation of architecture introduces ethical challenges related to data privacy [

99]. With the widespread use of digital platforms, architects and developers often collect user data, such as location information and interaction patterns. Protecting this data and ensuring informed consent are essential for maintaining public trust. Addressing these ethical concerns is critical to ensuring that technology enhances rather than detracts from the human experience of architecture.

Table 3 summarizes the ethical considerations as well as the positive and negative impacts of social media on architectural perception and engagement, offering a balanced view of their role in shaping architectural experiences.

5. Selected Case Studies

Tai Kwun in Hong Kong and the Kunsthaus in Graz, Austria, both exemplify iconic and star architecture (

Figure 4). Designed by renowned architects, these buildings stand out for their visual impact and cultural significance, embodying a tangible interplay between the past, present, and future. Tai Kwun is a revitalized heritage site that seamlessly blends restored historical buildings with contemporary design elements. Visitors can explore preserved colonial-era structures while engaging with modern cultural activities, bridging the city’s historical past with its vibrant present. Originally established after 1841 as Hong Kong’s main police station and prison, Tai Kwun holds significant historical importance [

101]. The transformation, led by Herzog and de Meuron, turned Tai Kwun into Hong Kong’s largest heritage conservation project, safeguarding crucial colonial architecture that might have otherwise been lost [

102]. The renovated compound opened to the public in phases, starting with the inaugural exhibition “100 Faces of Tai Kwun” on 29 May 2018.

The Kunsthaus Graz showcases a futuristic architectural design that stands in stark contrast to Graz’s historic cityscape [

103], prompting visitors to contemplate the evolution of architectural styles and future possibilities. Designed by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier and inaugurated in 2003, the Kunsthaus serves as an exhibition space for contemporary art and photography, as well as a venue for various cultural events. Its distinctive design, often referred to as the “friendly alien”, features enigmatic elements like nozzles and a blue bubble, intentionally diverging from traditional architectural forms to create a unique visual experience.

This study focuses on how the public represents and interprets these architectural works through digital media. By analyzing Instagram data, such as user posts, interactions, and shared content, we aim to assess how people engage with these buildings and perceive architectural spaces online. This analysis will provide insights into how iconic architecture shapes public perception and engagement on social media platforms.

5.1. Data Collection

We collected data through a combination of virtual observations on Instagram and physical site visits to Tai Kwun (21 June 2024) and Kunsthaus (12 September 2024). Digital documentation, including photographs, posts, hashtags, stories, and user-generated content on Instagram, was gathered to create a comprehensive dataset for analysis. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on visitor access and social media activity, we focused on posts (photos and videos) and stories from 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2024. To minimize biases related to accessibility, we focused on publicly accessible buildings, specifically museums and cultural or arts hubs like Tai Kwun and the Kunsthaus.

We intentionally selected case studies with moderate social media activity (600–800 posts during the selected period) to ensure a manageable and comparable sample size. This approach allowed us to concentrate on user interactions and architectural features without data being skewed by the extreme popularity of globally recognized landmarks.

Table 4 provides details of the selected case studies.

Given Instagram’s limited data accessibility through its API, we employed a third-party scraper to collect data exclusively from the official Instagram accounts of Tai Kwun and the Kunsthaus (from

rapidapi.com (accessed on 22 September 2024) and

www.notjustanalytics.com (accessed on 22 September 2024)). Our initial step involved gathering all posts published by these official accounts, then analyzing the interactions and popularity of each post and its related hashtags. For image preprocessing, we followed the method proposed by Gordo et al. [

104] to calculate a feature vector for each image. This feature vector, which captures essential details such as surface characteristics and color, was used in subsequent image classification tasks to filter and categorize the posts.

5.2. Filtering and Classification

To analyze the images, photos or videos, a two-step classification process was implemented. The first step involved identifying common photographic elements, leading to five primary image categories: (1) architecture, (2) events, (3) people, (4) artworks, and (5) other images unrelated to the buildings. The second step categorized the collected images into one of these five classes. While some images could overlap categories, the classifier was designed to identify the primary focus of each image.

In addition to image data, Instagram users typically include captions and hashtags that provide further context. Hashtags are often used to reference locations or describe features, while captions offer personal reflections or descriptions of experiences. These textual elements provide valuable insights into how users perceive and engage with buildings. To analyze this content, topic modeling was employed to extract common themes or keywords from the text. For example, topics might be represented by terms like “architecture”, “museum”, or “arts”. Once the topics were generated, they were manually grouped into four main categories: (1) architecture, (2) promotional events, (3) functions, and (4) other specific or incoherent topics that did not fit into the previous categories. For a detailed breakdown of these categories, refer to

Table 5. By combining image classification and topic modeling, this study reveals how social media influences the perception and engagement with architectural spaces, offering insights into how digital platforms shape public interaction with iconic buildings over time.

6. Data Analysis

This section analyzes user engagement with architectural spaces on Instagram by combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. The analysis focuses on three main aspects: (1) the visual and sensory representation of architecture as captured through on-site visits and Instagram posts; (2) analysis of images and captions or text; and (3) patterns of user engagement, assessed through metrics such as likes, comments, shares, and the use of specific hashtags. By exploring these aspects, the study seeks to uncover how digital platforms like Instagram influence the perception and experience of architectural spaces. This investigation is critical in understanding the broader mediatization of architecture in the digital age, where social media plays an increasingly pivotal role in both the dissemination of architectural design and the public’s interaction with it. The findings aim to provide insights into how architecture is represented, interpreted, and engaged with online, shedding light on new dynamics in architectural communication and audience participation facilitated by digital platforms.

6.1. Visual and Sensory Representation

Architectural spaces are experienced through multiple senses (sight, sound, touch, and even smell) that interact to create a holistic perception. This multi-sensory engagement shapes memory and emotion, embedding architectural experiences within our personal and collective histories [

13]. However, when these experiences are mediated through platforms like Instagram, this rich sensory interaction is often reduced to a purely visual representation. To explore this dynamic, we conducted on-site visits to Tai Kwun in Hong Kong (21 June 2024) and Kunsthaus Graz in Austria (12 September 2024), allowing for direct sensory and spatial observations of these iconic architectural sites.

At Tai Kwun, a heritage site and cultural center, the sensory experience is deeply connected to its historical layers. Walking through the former Victoria prison, the echo of footsteps on stone floors, the cool air in the shaded courtyards, and the rough texture of weathered walls create a sensory journey that evolves as one moves through different spaces [

64,

105]. These stimuli not only evoke the present moment but also connect visitors to the site’s colonial-era history. The smell of aging stone and the stark soundscape of enclosed spaces evoke the harshness of prison life, an experience difficult to capture through static Instagram images. In contrast, Kunsthaus Graz, with its biomorphic “friendly alien” design, offers a futuristic sensory experience. Its organic, curvilinear form invites tactile engagement, while the translucent building skin filters light in unexpected ways (

Figure 5). Inside, the interplay between natural light and smooth surfaces creates a fluid, evolving sensory environment. As visitors move through the space, the interaction of sound, light, and texture generates an immersive experience. Yet, Instagram typically focuses on the building’s unusual exterior, often overlooking the ongoing sensory and spatial interactions that define the full experience of the space.

Memory plays a crucial role in architecture, linking the past to the present by encapsulating both collective and personal histories. The sensory engagement of a building (its sights, sounds, and textures) helps anchor these memories [

14,

58]. For example, Tai Kwun uses digital projections of a prisoner’s silhouette to vividly evoke the site’s past as a prison (

Figure 6). These elements, combined with the surrounding sensory environment, shape how visitors remember and interpret the space’s historical significance. Similarly, Kunsthaus Graz leaves a lasting impression through its unconventional forms and dynamic interaction with light, allowing the space to evolve in memory as the sensory experience unfolds. Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology suggests that our perception of space is an embodied experience, shaped by the integration of all our senses. However, Instagram’s emphasis on visuality often limits this full-bodied interaction, flattening the richness of these spaces into mere visual snapshots. Martina Löw (2008) further argues that the arrangement of people, objects, and structures within a space, what she calls “spacing”, influences how we experience and remember it [

41,

106]. The sensory details, such as the sound of footsteps, the feel of textured walls, and the shifting light within spaces like Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus Graz, invite deeper engagement beyond what is captured on Instagram. Individuals with different thoughts, memories, emotions, and moods can perceive the same space differently [

63,

107].

Memory is also intricately tied to these sensory experiences. For instance, walking through Tai Kwun evokes a connection to its history as a prison, stirring emotions linked to that past. Similarly, the futuristic design of Kunsthaus Graz can elicit forward-looking thoughts, associating the space with innovation and change. These sensory experiences are essential to how we form memories of architectural spaces. As Husserl noted, even forgotten memories stored in the “sedimented unconscious” can resurface through sensory triggers like smell, touch, or sound, reinforcing the connection between space and memory [

108].

Walter Benjamin (1936) recognized architecture as a collective experience, shaped by the simultaneous interaction of many people with a space [

3,

109]. In the age of social media, this collective experience has evolved, allowing more people to engage with architectural spaces remotely, from anywhere at any time. Instagram extends access to these spaces beyond physical boundaries, enabling users to experience architecture even if they cannot visit the site in person. However, these digital interactions are often limited to visual and, in some cases, auditory elements, reducing the multi-sensory experience of physically being in a space. The tactile sensations, ambient sounds, and even smells that contribute to the full sensory experience are compressed into a two-dimensional format. Thus, while social media broadens access and enhances collective engagement, it simultaneously narrows the sensory depth, prioritizing sight and sound over the complete bodily interaction that defines in-person architectural experiences.

6.2. Image and Text Analysis

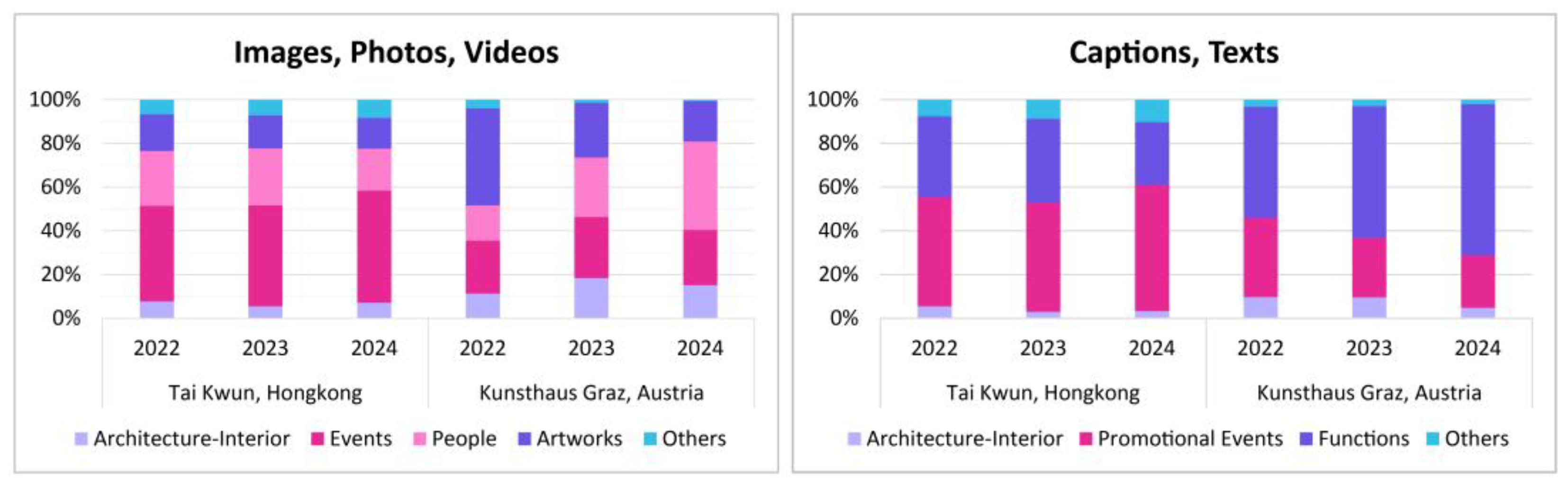

The classification results for both Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus reveal distinct patterns in how these iconic architectural spaces are visually represented and described on social media platforms (

Figure 7). For Tai Kwun, the most prevalent category was “Events”, representing 47% of the images, which highlights the site’s frequent use for public gatherings, performances, and exhibitions. The second most common category was “People” at 24%, suggesting that Tai Kwun’s interactive and social atmosphere is an essential element of its architectural experience. “Artworks” also featured prominently at 15%, indicating that Tai Kwun showcases a significant number of creative installations, while “Architecture-Interior” accounted for only 7% and “Others” for 7%. This suggests that Tai Kwun’s architectural elements may take a secondary role in visual representation compared to the events and people engaging with the space.

In contrast, for Kunsthaus, the distribution of image categories reveals different priorities. “Artworks” was the largest category, making up 29% of the images, emphasizing Kunsthaus’s strong focus on contemporary art exhibitions and installations. “People” and “Events” were also significant, comprising 29% and 26%, respectively, indicating a balanced engagement with both social interactions and art-related activities. Interestingly, “Architecture-Interior” had a more substantial representation at 15% compared to Tai Kwun, showing that Kunsthaus’s distinctive architecture, often dubbed the “friendly alien”, draws significant attention from visitors. The “Others” category was quite low at 2%, suggesting that most of the images remain closely related to the core themes of the site.

Regarding the text classification, the results indicate that both Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus focus on promoting events and functions, but there are some notable differences. For Tai Kwun, 52% of the captions centered around “Promotional Events”, reflecting the site’s cultural and social significance. “Functions” made up 35%, likely referencing the different roles the space plays within the community, while only 4% of captions focused on “Architecture-Interior”, further supporting the idea that Tai Kwun’s architectural features are not the main focus in user-generated content. At Kunsthaus, the dominant category for text classification was “Functions”, at 61%, reflecting the heavy emphasis on the building’s role as an exhibition space and cultural institution. Twenty-nine percent of captions were categorized under “Promotional Events”, and 8% under “Architecture-Interior”, indicating a slightly greater interest in the building’s architectural elements compared to Tai Kwun. The low percentage of “Others” in both cases (9% for Tai Kwun and 3% for Kunsthaus) suggests that most captions remained on-topic, emphasizing aspects directly related to the site’s purpose and design.

This analysis reveals the different ways in which users engage with and represent these two iconic architectural spaces, with Tai Kwun focusing more on its role as a hub for social interaction and cultural events and Kunsthaus showcasing a stronger focus on contemporary art and its unique architectural design. These patterns provide insights into how each space is perceived and valued by the public, both visually and in textual representations.

6.2.1. User Engagement Trends

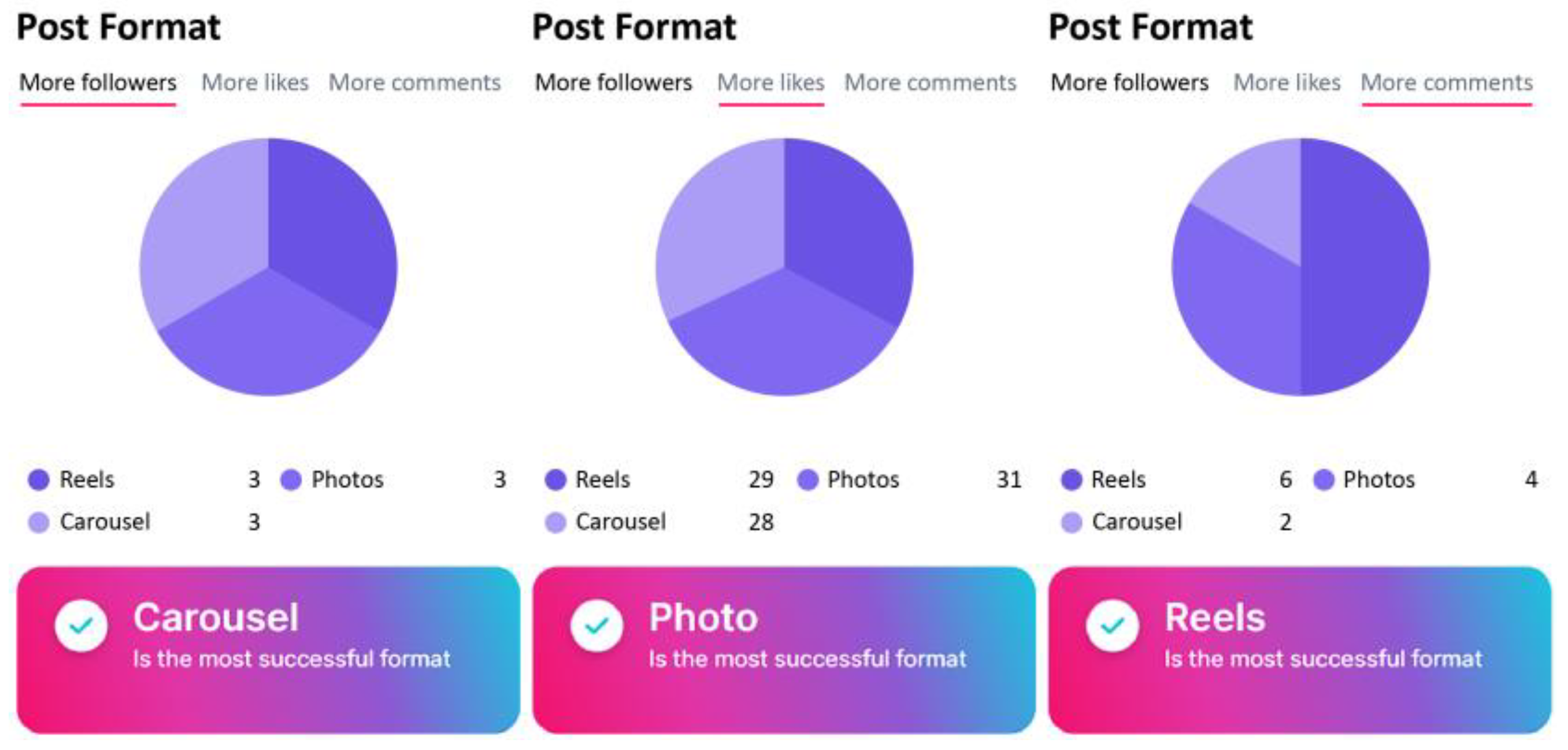

Based on

Figure 8 and

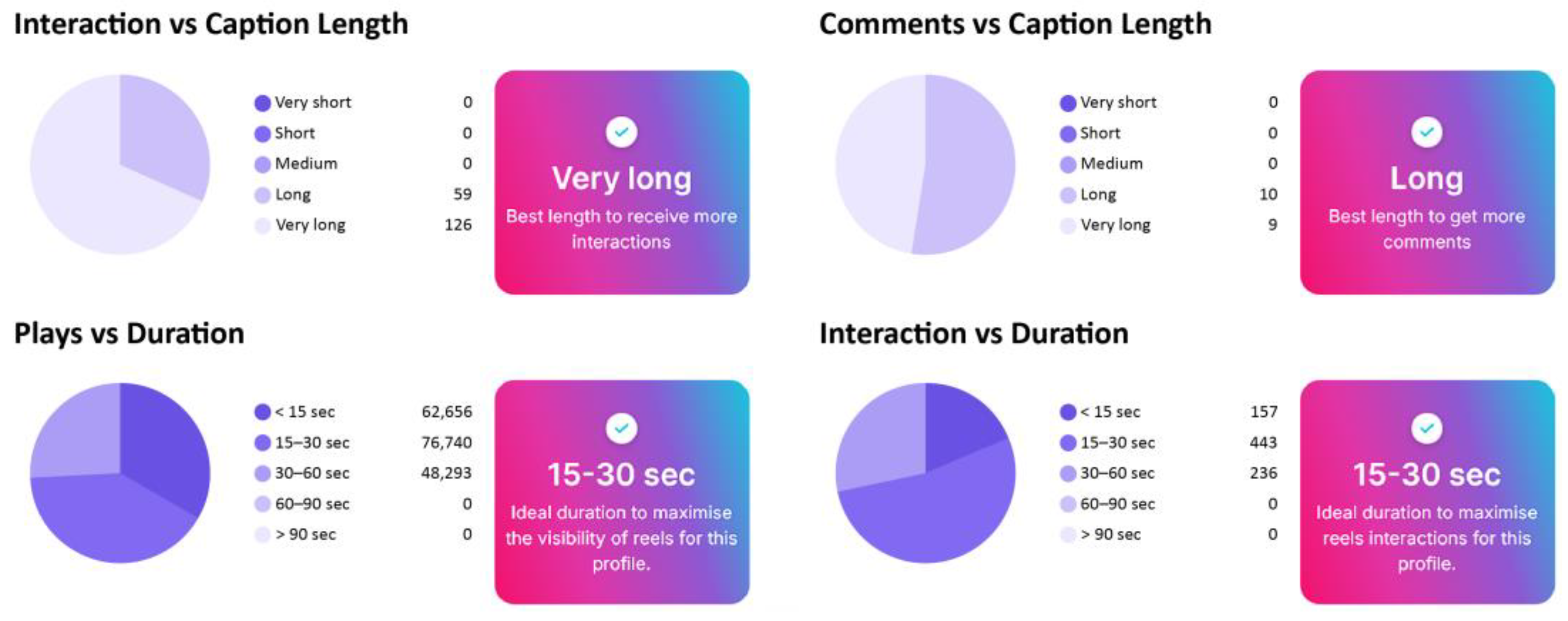

Figure 9, we analyzed Tai Kwun’s Instagram data, focusing on post formats, caption lengths, and their relation to user engagement, such as likes, comments, and follower growth. These diagrams reveal key patterns and highlight the strategies that perform best on Instagram. Reels, which are short video clips, emerge as the most effective format for generating both likes and comments. This is unsurprising given that Instagram’s algorithm tends to prioritize video content, which retains user attention longer than static images. The interactive nature of reels, showcasing real-time events, performances, or architectural highlights, helps drive significant user engagement.

Carousel posts, which allow users to swipe through multiple images in a single post, were the most effective in gaining new followers. This format provides a more comprehensive view of exhibitions, events, or architectural highlights, which seems to captivate users, leading to higher follower growth. In contrast, single-photo posts, while still used frequently, were less effective in generating engagement. This indicates a shift in user preference toward more dynamic and content-rich formats over static images.

Figure 9 highlights the impact of caption length and video duration on user engagement. Posts with very long captions receive the most interactions, suggesting that users appreciate detailed, informative captions that provide context or narratives behind the images. These longer captions, often discussing the significance of Tai Kwun’s events or architectural elements, foster deeper connections with the audience. Similarly, long captions performed best in terms of comments, likely because they encourage more thoughtful interaction and discussions. This trend aligns with current social media practices where storytelling plays significant roles in driving user engagement. In terms of video duration, videos between 15 and 30 s generate the most plays and interactions. This preference for concise content reflects Instagram users’ need for quick, easily digestible videos on a fast-scrolling platform. Longer videos showed lower engagement, emphasizing the importance of brevity. For Tai Kwun, short videos highlighting exhibitions, events, or architectural tours are more likely to attract views and interactions than longer, more detailed content.

In the case of Kunsthaus (

Figure 10), carousel posts were the most effective format for growing followers, reflecting a preference for posts that offer multiple perspectives on exhibitions or installations. Photo posts garnered the most likes, indicating that static images of iconic architectural elements or artworks still resonate strongly with Kunsthaus Graz’s audience. Reels, while effective for generating comments, performed weaker for likes and follower growth.

Figure 11 further shows that posts with long captions led to the highest levels of interaction and comments for the case of Kunsthaus Graz. These captions provided detailed descriptions or narratives that engaged the audience by sharing stories behind artworks or events. This mirrors the pattern seen with Tai Kwun’s audience, where longer captions similarly led to greater engagement. However, while in-depth content was valued, excessively lengthy captions did not perform as well, suggesting users prefer detailed but not overwhelming text. Kunsthaus also generates higher engagement with slightly longer videos (60–90 s), indicating that its audience values more detailed explorations of exhibitions or architectural features. This differs from Tai Kwun, where shorter videos (15–30 s) were more successful.

When comparing Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus Graz, distinct differences in audience preferences and engagement patterns emerge. Tai Kwun’s followers tend to favor reels and shorter content, while Kunsthaus’s audience responds more to static photo posts and longer videos. Additionally, Tai Kwun’s followers engage more with very long captions, while Kunsthaus’s audience prefers detailed but more concise captions. An important factor influencing user behavior on Instagram is the fear of missing out (FOMO), which drives users to return frequently to stay updated on events, exhibitions, and cultural happenings [

110]. For Tai Kwun, the FOMO effect is most apparent in the success of reels and short videos, which provide real-time updates and create a sense of immediacy. On the other hand, Kunsthaus Graz’s audience, while still influenced by FOMO, is more drawn to reflective content, particularly photo posts and detailed narratives. Surveys further highlight that a significant portion of Kunsthaus visitors are drawn primarily to its architecture, which explains the high engagement with posts featuring the iconic “friendly alien” design. In both cases, Instagram plays a crucial role in fostering FOMO-driven engagement, encouraging users to return frequently. The platform’s visual-centric, algorithm-driven system rewards dynamic and visually appealing content, benefiting both Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus Graz by amplifying their cultural and architectural appeal.

6.2.2. Correlation Between Content Types and User Engagement

In analyzing the correlation between post activity (such as likes, comments, and shares) and the content types (categorized as architecture, events, people, artworks, and others), several distinct patterns emerged regarding user engagement on Instagram. This analysis specifically focused on Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus Graz, revealing how different types of content impacted audience interaction and which posts attracted the most engagement. Event-related posts demonstrated the highest positive correlation with user engagement, particularly in terms of likes and comments. For both Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus, the correlation between event-driven content and user engagement was strong (r ≈ 0.85). This finding aligns with the work of Paasonen (2016), who argues that social media users are drawn to dynamic, real-time content that reflects their desire to remain socially and culturally connected [

111]. Events such as public gatherings, performances, and exhibitions provided users with engaging content that allowed them to feel part of the cultural activity, even if they were not physically present. The ability of such posts to foster a sense of community engagement reflects the importance of content that portrays active participation and interaction.

Posts featuring people, whether visitors, groups, or individuals engaging with the space, also showed a strong positive correlation with user engagement (r ≈ 0.70). This reflects findings by Smock et al. (2011), who noted that images involving human interaction tend to foster greater emotional responses and connections, making users more likely to engage [

112]. By portraying social participation within these architectural spaces, both Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus capitalized on the human element of their events and activities, drawing users into a deeper sense of belonging and community interaction. Artworks, particularly at Kunsthaus, generated a moderate positive correlation with engagement (r ≈ 0.60), as users were drawn to the aesthetic and creative aspects of contemporary installations. According to Colomina (2000), visual content that highlights artistic expressions often appeals to niche audiences who seek aesthetic stimulation through social media [

67]. While Tai Kwun’s focus on events outweighed its emphasis on artworks, Kunsthaus’s central role as an art institution made posts about exhibitions and installations more engaging for users, reinforcing the institution’s cultural relevance.

However, posts centered on architectural features, categorized as “Architecture-Interior”, demonstrated a weaker correlation with engagement (r ≈ 0.45). While the aesthetic appeal of architectural design is often highlighted on Instagram, these posts did not generate as much interaction as content focused on events or people. This aligns with Frampton’s (1986) argument that modern architectural representation in media often reduces buildings to mere visual spectacles, overshadowing their social and functional aspects [

68]. For Tai Kwun, where the historical and contemporary architectural features were often secondary to cultural events, architecture-related posts attracted lower engagement. By contrast, Kunsthaus’s distinctive and iconic architectural design attracted relatively more engagement, reflecting its prominence as a visual landmark.

According to Benjamin (2008), buildings are both used and perceived, a duality evident in how Instagram reshapes user engagement with architecture [

109]. Visual-centric platforms like Instagram prioritize aesthetic experiences, where spectacular designs initially capture users’ attention [

95]. However, as the findings show, long-term engagement is often driven by cultural and social experiences within these spaces. This aligns with Lushey (2021), who argues that social media fosters short-term visual attraction but requires deeper, recurring experiences to sustain user interaction [

9]. By leveraging Instagram’s capabilities to integrate both visual appeal and social interaction, Tai Kwun and Kunsthaus Graz successfully maintain engagement. Their strategic use of events, artworks, and social interactions on Instagram highlights how these institutions effectively utilize digital platforms to extend their reach, engage diverse audiences, and foster lasting connections with their spaces.

7. Conclusions

This paper underscores the profound impact of Instagram on the perception and engagement with architectural spaces in the digital age, using Tai Kwun in Hong Kong and Kunsthaus Graz in Austria as case studies. The findings reveal that Instagram often prioritizes visual aesthetics, compressing the temporal and multisensory aspects of architecture into snapshot moments. This visual dominance may lead to superficial engagement, where the depth of architectural experience is overshadowed by the pursuit of "Instagrammable" content. However, beyond this surface-level interaction, Instagram also offers opportunities for enhanced engagement. By allowing users to revisit and interact with architectural spaces across different times and settings, the platform extends the temporal experience and transforms buildings into dynamic, evolving narratives that blend the past, present, and future.

Buildings, through Instagram, are no longer static objects but part of a broader cultural landscape, where the temporal experience can be compressed, extended, or reinterpreted by users. These insights highlight the dual role of Instagram in both enhancing accessibility and fostering global conversations about architecture, while also posing ethical considerations regarding authenticity and the commodification of architectural spaces. It is crucial for architects and stakeholders to recognize these trends and strive to balance aesthetic appeal with the preservation of architectural integrity and experiential depth. By incorporating interactive content, real-time events, and user-generated posts, they can foster deeper, more meaningful engagement. Additionally, balancing aesthetics with cultural and historical context ensures that architecture remains significant in both the digital and physical worlds. This approach will bridge the gap between the transient nature of digital media and the lasting experience of the built environment, contributing to a richer, more embodied perception of architecture in today’s digital era.