1. Introduction

The interaction between people and their physical environment is a subject studied across various disciplines. Professionals who conceive and design housing and legislation have a duty to achieve inclusiveness. Housing should be designed to be used by all people, regardless of age, gender, ability or different personal situations, and should foster environments that enable the full implementation of all the activities that make a dwelling a home [

1].

Research in fields such as architecture, engineering, ergonomics, occupational therapy and psychology has direct applications [

2]. The characteristics of the built environment significantly impact both quality of life and health of its inhabitants [

3].

Housing is a fundamental element of life, as it is the place where people create their own environment and develop their closest personal relationships. Housing provides shelter, privacy and well-being [

1]. Accessible housing must, from the outset, guarantee the autonomy, safety, dignity, comfort and time savings of the person who lives in it, as well as those who visit it [

4]. Housing, as a social good, must meet the basic habitability needs of its occupants at the different stages of their lives. Therefore, adaptability or convertibility criteria should be incorporated into housing, so that the user can make the necessary modifications at any given time, at low cost and with minor interventions, if necessary, without having to change their home or give up their autonomy [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

The design of a building that can be used by everyone without adaptation or subsequent specialisation must meet two requirements: mobility (being able to reach any corner of the building) and functionality (carrying out one’s own activities in any space, guaranteeing safety of use) [

10]. Housing conditions have an impact on health; a home is healthy when it promotes a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being. In addition to the physical structure of the dwelling and the extent to which it supports health, a dwelling also provides a sense of home, including a sense of belonging, security and privacy [

11]. The World Health Organization provides policy guidance and technical support to promote healthy housing for all [

12].

Better housing can save lives, prevent disease, improve quality of life, reduce poverty, help mitigate climate change and contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Demographic and climate changes make housing increasingly important for health. The world’s urban population is projected to double by 2050, and new housing solutions will be needed [

10,

13].

Housing is the type of building that is subject to the most regulations, which affect both the design and the quality of construction, making universal design more expensive and difficult [

14,

15]. Universal accessibility consists of planning, designing, building, rehabilitating and maintaining the environment in such a way that it meets all the needs and requirements of every person, regardless of age, circumstances or ability, based on the characteristics of comfort, safety and personal autonomy [

4,

16]. Accessibility is seen as a social challenge for the 21st century; it implies a change towards humanism, which means dignifying societies and ensuring that human rights are respected so that the lives of citizens can be developed with full autonomy, comfort and safety [

1].

In recent years, responsibilities have been assumed, and legislative developments have been favourable. The right to universal accessibility is being increasingly demanded by the whole population. However, the existence of standards does not guarantee the creation of inclusive spaces where everyone can use and enjoy a home [

16].

Faced with this situation, the following concerns arise: what legislation exists in Spain to achieve accessibility in housing for all people, and how do existing regulations allow adequate control of universal accessibility in any Spanish home? Therefore, it is essential to analyse and understand the theoretical bases and regulations on accessibility as applied to housing. All of this is with the aim of providing a basis from the outset in design to ensure the inclusion of all citizens.

The aim of this study is to review the current Spanish regulations on accessibility in the housing sector, in order to facilitate access in a non-discriminatory and independent manner and to guarantee the safety of each resident.

This general objective is further detailed through the following specific objectives: (a) To review the literature and legislation on housing accessibility. (b) To identify and select the current regulations in force in Spain. (c) To prioritise relevant laws, decrees and plans concerning accessibility. (d) To assess the application of these regulations. (e) To propose suggestions and recommendations to ensure mandatory compliance.

2. Materials and Methods

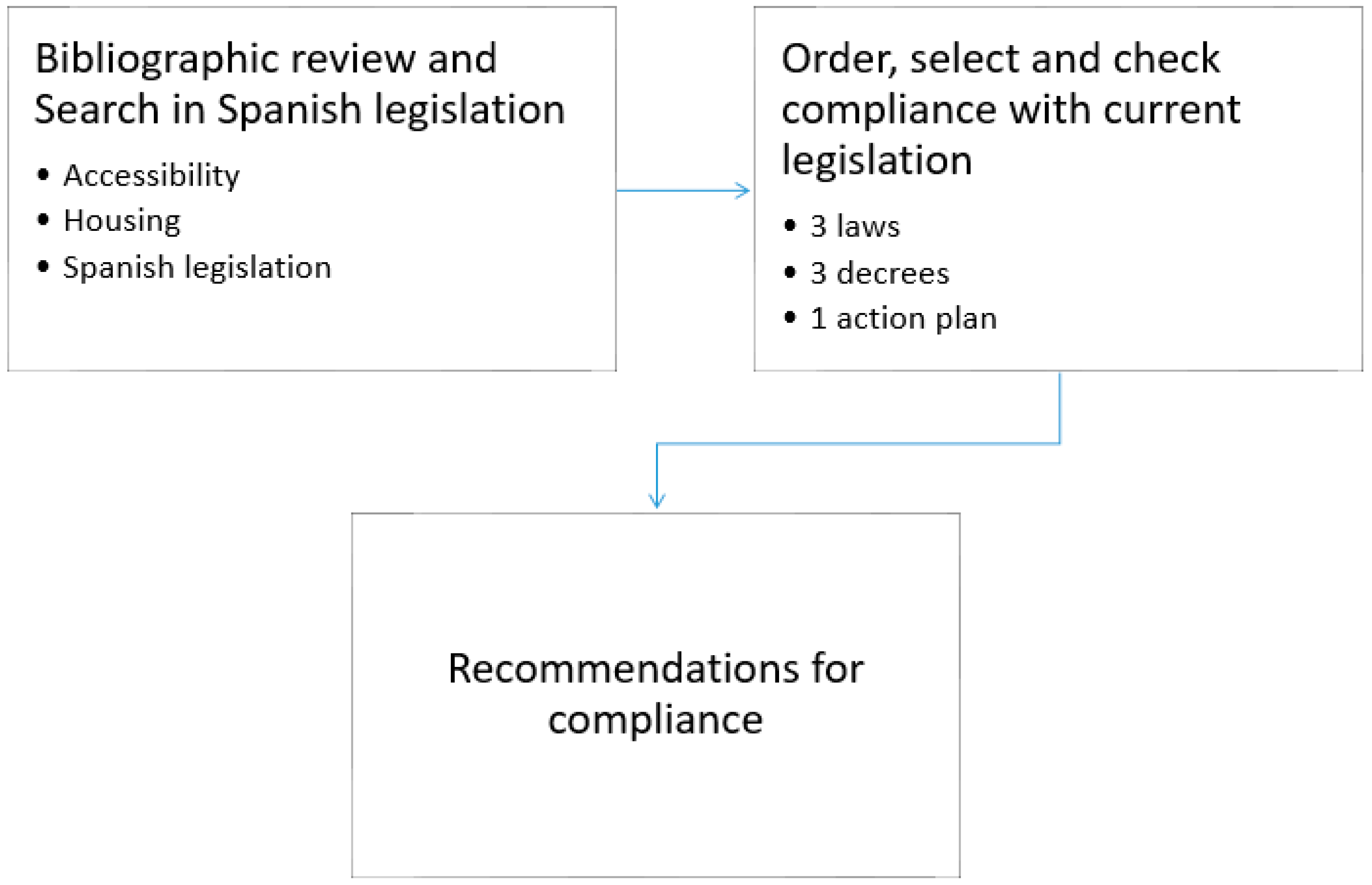

The method employed in this study is exploratory research. It is described in

Figure 1.

The first step involved conducting a search for references related to accessibility and housing. For the literature review, we employed the PRISMA method, searching the Scopus and Web of Science databases using the keywords: “accessibility”, “housing” and “Spanish legislation”. The search was restricted to documents in English and Spanish. No restrictions were placed on the publication year, as the objective was to examine current regulations within the Spanish legal system that address housing and accessibility comprehensively. Then, the regulations were ordered and systematised by researching both general and state regulations. According to this criterion, only legislation in force at the end of the study, 31 December 2023, was selected.

In order to focus on the regulatory universe to be analysed, the Technical Building Code was followed, including the regulations, decrees and laws in force that must be complied with. After compiling the relevant regulations, we conducted a thorough review of the laws currently in force.

In order to facilitate the analysis of the legislation found, a double matrix table is used, highlighting the content subject to regulation and the type of regulation.

3. Results

The main regulations regarding accessibility in housing in Spain include the Law on the Management of Buildings (LOE), together with the Technical Building Code (CTE); Law 8/2013 on Urban Rehabilitation, Regeneration and Renewal; and the requirement for neighbourhood associations to comply with the accessibility provisions of the Building Assessment Report; Royal Legislative Decree 7/2015, of 30 October, which approves the revised text of the Law on Land and Urban Rehabilitation; the State Plan for Access to Housing 2022–2026; and Law 6/2022 on Cognitive Accessibility (

Table 1).

These regulations aim to ensure that all citizens have decent, adequate and accessible housing, which is one of the fundamental rights of every person, as laid down in Royal Legislative Decree 1/2013, of 29 November, approving the consolidated text of the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and their Social Inclusion.

3.1. Law 38/1999, of 5 November 1999, on the Regulation of Construction

Law 38/1999, of 5 November 1999, on the regulation of construction, regulates construction processes and establishes the obligations and responsibilities of the parties involved in construction (

Figure 2). It ensures quality through compliance with basic requirements and protects users. Article 3, among the basic requirements for construction, describes those related to functionality. In Section A.2, the law specifically addresses accessibility, stating that buildings must allow persons with reduced mobility and communication abilities to access and move around the building under the conditions set out in its specific provisions. In Section C.4, it states that the requirements of the building in terms of habitability must comply with the functional aspects of both construction and installation elements that allow for the satisfactory use of the building [

17]. In its second additional provision, it authorises the government to approve a technical building code by royal decree.

3.2. Royal Decree 314/2006 of 17 March 2006 Approving the Technical Building Code (CTE)

Royal Decree 314/2006 of 17 March 2006 approved the Technical Building Code (CTE), which regulates the basic quality requirements that buildings, including their installations, must meet in order to comply with basic safety and habitability requirements (

Figure 3). One of these requirements is safety of use and accessibility. The aim of this basic requirement is to facilitate non-discriminatory, independent and safe use of buildings. The CTE is divided into two sections. The first contains the general provisions (scope, structure, classification of uses, etc.) and the requirements that buildings must fulfil in order to meet the requirements of safety and habitability. The CTE has been amended several times: by Royal Decree 173/2010, by Royal Decree 732/2019 of 20 December, by Order VIV/984/2009 of 15 April and, most recently, by Royal Decree 450/2022 of 14 June [

18].

3.3. Royal Legislative Decree 1/2013, of 29 November, Approves the Revised Text of the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Their Social Inclusion

Royal Legislative Decree 1/2013, of 29 November, approves the revised text of the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and their Social Inclusion (

Figure 4). This law unifies all existing regulations on the subject and establishes that disability must be taken into account in all policies and by all administrations. In addition, for the first time, it explicitly includes respect for the autonomy and will of persons with disabilities and their right to make decisions through information adapted to their personal characteristics. It introduces concepts that have been included in European legislation, such as discrimination by association or harassment on the grounds of disability. It also set 4 December 2017 as the deadline for guaranteeing accessibility in urbanised public spaces and buildings that are susceptible to reasonable adjustments. It is essential to highlight some concepts that are very important to take into account and that should guide the holistic vision of accessibility and its application in The Accessible City. Some of these concepts include Universal accessibility: the condition that environments, processes, goods, products and services, as well as objects, instruments, tools and devices, must meet in order to be understandable, usable and practicable by all people under appropriate conditions. Universal design or design for all people: the activity by which environments, processes, goods, products, services, objects, instruments, programs, devices and tools are conceived or planned from the outset in such a way that they can be used by all people to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialised design. Universal design, or design for all persons, does not exclude assistive products for specific groups of persons with disabilities when they need them. Reasonable adjustments: the necessary and appropriate modifications and adaptations of the physical, social and attitudinal environment to meet the specific needs of persons with disabilities. These adjustments should not impose a disproportionate or undue burden when required in a particular case in an effective and practical manner, in order to facilitate accessibility and participation, and ensuring that persons with disabilities can enjoy or exercise all rights on an equal basis with others. Transversal disability policy: this principle ensures that the actions of public administrations are not limited to specific plans, programmes and actions designed exclusively for these people, but also includes policies and lines of action of a general nature across all areas of public action, where the needs and demands of persons with disabilities are taken into account. It proposes recommendations aimed at improving the level of accessibility of the current housing stock in Spain and suggests carrying out subsequent measurements with a periodicity that can give an idea of the evolution of the accessibility of housing in Spain [

19].

3.4. Royal Decree 7/2015, of 30 October, Which Approves the Consolidated Text of the Land and Urban Rehabilitation Act

Royal Decree 7/2015, of 30 October, which approves the consolidated text of the Land and Urban Rehabilitation Act (

Figure 5), expresses the need for the evaluation of buildings to include the basic conditions of universal accessibility and non-discrimination in access to and use of buildings, in accordance with current regulations. It also establishes the basic conditions necessary to ensure equality in rights and obligations related to land, guaranteeing citizens an adequate quality of life and the right to enjoy decent, adequate and accessible housing [

20].

3.5. Law 49/1960 of 21 July Horizontal Property Law

Law 49/1960, of 21 July, the Horizontal Property Law, regulates the relations, rights and obligations between the owners or neighbours of several properties belonging to the same community or building (

Figure 6). The current legal regime of horizontal property is neither equitable nor does it fully guarantee access and maintenance in conditions of dignity and adequacy for all people [

21]. Law 10/2022, of 14 June, on Urgent Measures to Promote the Rehabilitation of Buildings, is part of the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan. This law responds to the fact that more than 75% of residential buildings are inaccessible and seeks to promote comprehensive actions that contribute to improving the quality, state of conservation, accessibility and digitalisation of buildings. It also promotes the construction of social rental housing that meets the highest standards of quality and efficiency. Architecture is understood as a multidisciplinary activity, resulting from the collective and coordinated effort of different professionals, each contributing knowledge from their respective fields [

22].

3.6. The Royal Decree That Regulates the National Plan for Accessibility to Housing 2022–2026

The Royal Decree that regulates the National Plan for Accessibility to Housing 2022–2026 includes a programme for improving accessibility in and to housing, with the aim of promoting improved accessibility (

Figure 7) for (a) the installation of lifts, stair lifts, ramps or other accessibility devices, including those adapted to the needs of persons with sensory or intellectual disabilities, and their adaptation, once installed, to the relevant sectoral regulations. (b) The installation or provision of assistive devices, such as cranes or similar devices, to allow access to and use of common elements of the building, where appropriate, such as gardens, sports areas, swimming pools and other similar facilities by persons with disabilities. (c) The installation of information or warning devices, such as light or sound signals, to guide the use of stairs, lifts and the interior of the dwelling. (d) The installation of electronic communication elements or devices between the dwelling and the outside, such as video intercoms and similar devices. (e) The installation of home automation and other technological advances to promote the personal autonomy of the elderly or persons with disabilities. (f) Any intervention that enhances the universal accessibility of spaces inside single-family, terraced or multi-family dwellings covered by this programme, as well as improvements to evacuation routes. This includes works aimed at enlarging the circulation spaces inside the dwelling that comply with the conditions of the Technical Building Code for Accessible Dwellings, as well as improving accessibility conditions in bathrooms and kitchens [

23]. And (g) any intervention that improves compliance with the parameters established in the Basic Document of the Technical Building Code DB-SUA, Safety of Use and Accessibility [

4].

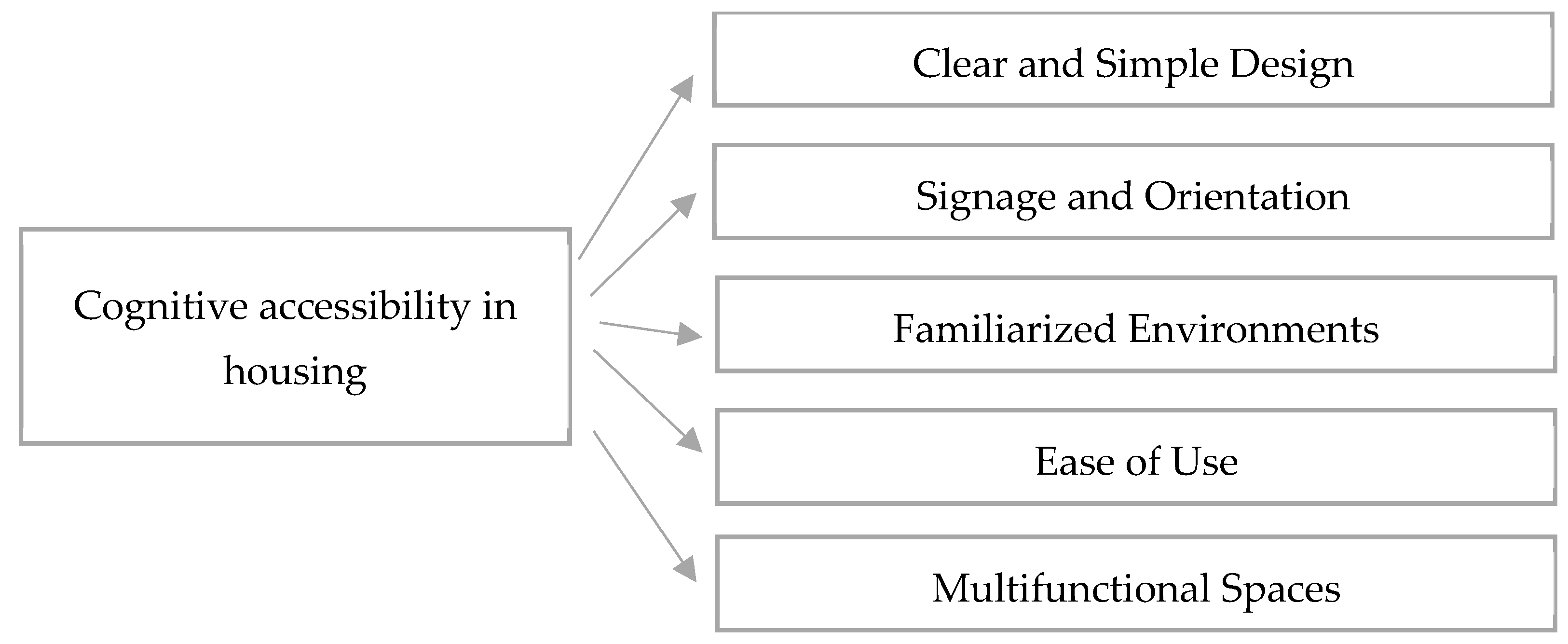

3.7. Law 6/2022, of 31 March, on Cognitive Accessibility

Law 6/2022, of 31 March, on Cognitive Accessibility amends the consolidated text of the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and their Social Inclusion, approved by Royal Legislative Decree 1/2013, of 29 November (

Figure 8), to define and regulate cognitive accessibility and its requirements and conditions. Recognised within the framework of universal accessibility, this concept broadens the definition of universal accessibility, giving it a greater and more complete dimension. It applies to environments, buildings, processes, goods, products, services, objects, tools, instruments, technologies and devices, making them easier for everyone to understand [

24]. It implies that the basic conditions of accessibility are regulated, without prejudice to the powers of the Autonomous Communities, emphasising the cognitive dimension and defining these basic conditions of cognitive accessibility in Article 29 bis. It establishes deadlines for the fulfilment of these basic conditions and obliges the Government to carry out diagnostic studies of the state of cognitive accessibility within a period of two years, as well as to approve the II National Plan for Accessibility in Public Administrations. The creation of the Spanish Centre for Cognitive Accessibility within the Royal Disability Council is approved. Cognitive accessibility aims to make the world easier to understand [

24,

25].

For this reason, three laws (1960, 1995 and 2022), three decrees (2006, 2013 and 2015) and a State Plan relating to housing accessibility are presented. The objectives of these regulations focus on defending the rights of all individuals through the principle of universal accessibility. They establish obligations and responsibilities for all stakeholders involved in construction, in accordance with the basic quality requirements set out in the Technical Building Code. These regulations mandate the assessment of buildings and the implementation of a programme to improve accessibility, including cognitive accessibility.

4. Discussion

There has been obvious progress in accessibility regulations in Spain, although more emphasis should be placed on compliance. Tools and resources must be provided to facilitate their effective implementation.

Despite awareness-raising efforts, existing regulations and manuals, greater involvement is still needed to adapt legislation to the needs of each individual, as well as to disseminate it and enforce compliance [

26]. Therefore, it is necessary to know the existing regulations on accessibility in housing in order to achieve their practical application [

16]. According to the UNESCO Chair, housing needs an adequate policy to be effective, a global housing policy that covers all dimensions, and it also needs the participation of interested parties in decision-making [

27].

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) also emphasises that housing policies must guarantee fundamental rights and be based on a holistic vision [

12]. This requires mechanisms that are diagnostic, systematised, exportable, automatable and rapidly updated, linking the many interrelated areas. These mechanisms should assess urban housing vulnerability and prioritise interventions based not only on the impact of climate change, but also on the health and well-being of people.

In 2013, a study on the accessibility of housing was published, identifying the main difficulties that can be found in housing and its surroundings. The study highlights the small size of many dwellings, the inadequate distribution and the lack of flexibility to adapt to changes that occur or result from the passage of time. It also emphasises the importance of accessibility in human relations and the factors that contribute to coexistence in the home, the existence of demands for technological solutions, automation and advanced systems that facilitate comfort, savings and security in the home and the general lack of sensitivity and resources to carry out the necessary reforms [

1]. A decade later, the list of accessibility demands is long and varied, mainly due to non-compliance or a lack of commitment to implementing mechanisms for access to fundamental rights for millions of people.

The legal deadline for the accessibility of all public environments, services and products that can be reasonably adapted expired in 2017 [

19]. However, there does not seem to be an ongoing strategy aimed at achieving full compliance with this mandate.

The way in which accessibility problems are dealt with depends on the specific area (urban planning, housing, communication or signage). Generally speaking, there are action strategies to avoid creating a second parallel environment for persons with disabilities, as this can often be discriminatory and exclusive [

27]. The ideal is, therefore, to build spaces and design products and services that can be used by all citizens regardless of their characteristics [

2].

The efforts made in recent years to improve universal accessibility in housing are recognised, although they seem to be seen as a mere procedures with the sole aim of complying with regulations. The reasons for solutions should be known in order to be effective in meeting the needs of all people [

10,

28,

29].

Addressing housing accessibility requires the development of open and inclusive infrastructure that allows for the participation of diverse perspectives and disciplines that focus on housing as a field of study [

2,

3,

30,

31,

32,

33]. The quality of housing and respect for the built environment are matters of public concern. All professionals have a significant responsibility for the health, safety, well-being, cultural interests and sustainability of the built environment. This responsibility must be clearly defined in legislation and included in educational efforts to raise awareness in society. The public needs to understand how their environment is created, how buildings make a difference to their lives and how they can participate in the design and construction process.

Accessible housing aims to improve the quality of life and promote personal autonomy. This is also one of the objectives of home automation, considered as the set of technologies applied to the control and intelligent automation of the home, allowing for efficient management, efficient use of energy, and providing security and comfort, as well as communication between the user and the system. The development of buildings in today’s society must take into account infrastructure and technological solutions that guarantee universal accessibility for all groups that need it, in compliance with current legislation, while adapting homes to people’s needs. It must also be taken into account that the needs of the inhabitants of the dwellings evolve over time, so it is necessary to consider the incorporation of infrastructures that facilitate the adaptation of the dwellings to these new needs [

34,

35,

36].

From the point of view of global sustainability, according to Rueda et al. [

37], it is necessary to change the direction of real estate activity by creating a long-term vision for the construction, maintenance and use of housing. The objectives needed to achieve sustainable cities and communities are 1. Improve the material conditions that influence the reduction of poverty and the improve the conditions and duration of life of the subjects that live there, including technical conditions of construction; 2. Promote social inclusion and justice, ensuring access to housing for disadvantaged groups and improving the conditions of accessibility of buildings for dependent people; 3. Ensure safe construction that allows survival, a construction that respects the physical environment (including protection against climate change and increased temperatures and protection of the biosphere and the rest of the world’s species affected by the uncontrolled growth of the human population) [

38].

The studies found on accessibility regulations in the housing sector are outdated, as in other countries [

14,

39]. However, the problems identified are still unresolved, even after the deadlines for the application of all the laws in force have passed. The aim of this study is to insist on the degree of compliance, so that all those responsible for all application variables, according to their respective responsibilities, take into account universal accessibility and design for all people.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, accessibility is a fundamental right for the entire population that must be respected. All stakeholders involved must internalise the principles of accessibility. To ensure compliance, regulations need increased oversight and supervision. Furthermore, accessibility criteria should be integrated from the initial phase of construction, with applicability extending into subsequent phases of rehabilitation (

Figure 9).

Overall, after reviewing and analysing the legal material regulating accessibility in housing, it is evident that there is robust legislation featuring innovative concepts and ambitious objectives. However, it is necessary to raise awareness in society that housing is a right and that the regulations are binding. Housing must be designed according to the needs expressed by the occupants in order to achieve inclusive buildings. It is essential to incorporate accessibility measures based on home automation that facilitate independent living and increase personal autonomy from an inter-professional approach.

Currently, stakeholders involved in the management of accessibility in housing have not yet internalised the concept of accessibility, and the processes used for its application are insufficient to achieve accessibility effectively. Its application still depends on economic resources and the will to implement it.

Non-compliance frequently stems from a lack of awareness regarding accessibility as both an enhancement and a right for the general population. Everyone may encounter physical, sensory or cognitive barriers at some point in their lives. Compliance with the regulations must be demanded, and agreements must be reached to promote progress in the accessibility of the environment and the dwellings themselves from the moment they are built. Better control and monitoring of compliance with existing legislation are also needed to implement all the planned measures to improve housing and technological progress.

We need to appreciate the progress that has been made in terms of accessibility, not only in terms of legislation, but also in ensuring that universal accessibility is understood as a right that allows the full exercise of citizenship rights and duties in all areas of life. However, there is still no common awareness of accessibility as an improvement and a right of the general population.

This means that accessibility criteria must be taken into account from the outset, maintained for the necessary period of time and incorporated in the event of changes and urban redevelopment phases.

Below are some possible suggestions for improvement in this area (

Table 2).

Firstly, when it comes to accessibility, there is still a need to put an end to non-compliance with regulations such as those contained in Royal Decree 1/2013 on the mandatory nature of accessibility in public environments, services and products, which states that everything should be accessible by 2017. The National Reference Centre for Persons with Disabilities proposes the creation of a National Fund for Universal Accessibility, which would allocate 1% of what is allocated annually to public works, infrastructure and new technologies in the General State Budgets.

Secondly, it is proposed to be proactive, as citizens, in identifying the lack of accessibility in housing, so that the measures presented are developed and implemented in a timely manner to provide solutions. Compliance with the aspects already regulated must be demanded, but agreements must also be reached to promote progress in the accessibility of the environment and technology.

Thirdly, in order to ensure that those responsible for guaranteeing these standards share the same criteria, training can be provided on accessibility, not only to improve it but also to ensure that its application does not present any shortcomings, so that control is complete, methodical and orderly. Better planning is also needed to ensure that evaluations are carried out before, during and after each action and that accessibility is ultimately a constant and cross-cutting criterion. Audits and external support can be added to evaluate and complement the evaluation processes. The development of accessibility plans to establish the basis for action can be another tool for improvement in the area of universal accessibility.

Fourthly, the Horizontal Property Law still does not meet the basic requirements of safety, habitability and universal accessibility for citizens. It is essential to ensure that the principle of accessibility is included in the common elements of buildings and that the Autonomy Law includes a wide range of compatible support services for community living, such as personal assistance and home help.

Fifthly and finally, cognitive accessibility must also be a key element of construction and should be present in texts, posters, technologies and pictograms to make the world easier to understand.

In short, there is still a long way to go to achieve decent, safe and accessible housing for all in Spain, despite the existence of legislation that regulates it. This research presents a compilation of the legislation and some proposals to help guarantee this objective, knowing that its application is the responsibility of all the stakeholders involved. We must continue to focus on innovation, digitalisation, sustainability and the application of cutting-edge technologies, methods and systems that contribute to the improvement of accessible housing.