Skeletal Muscle Androgen-Regulated Gene Expression Following High- and Low-Load Resistance Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach

2.2. Participants

2.3. One-Repetition Maximum (1RM) Bench Press and Leg Press Assessments

2.4. Resistance Exercise Protocol

2.5. Body Composition, Dietary, and Hydration Analysis

2.6. Skeletal Muscle Biopsies

2.7. Venipuncture

2.8. Serum and Intramuscular Hormone Analysis

2.9. mRNA Gene Expression Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

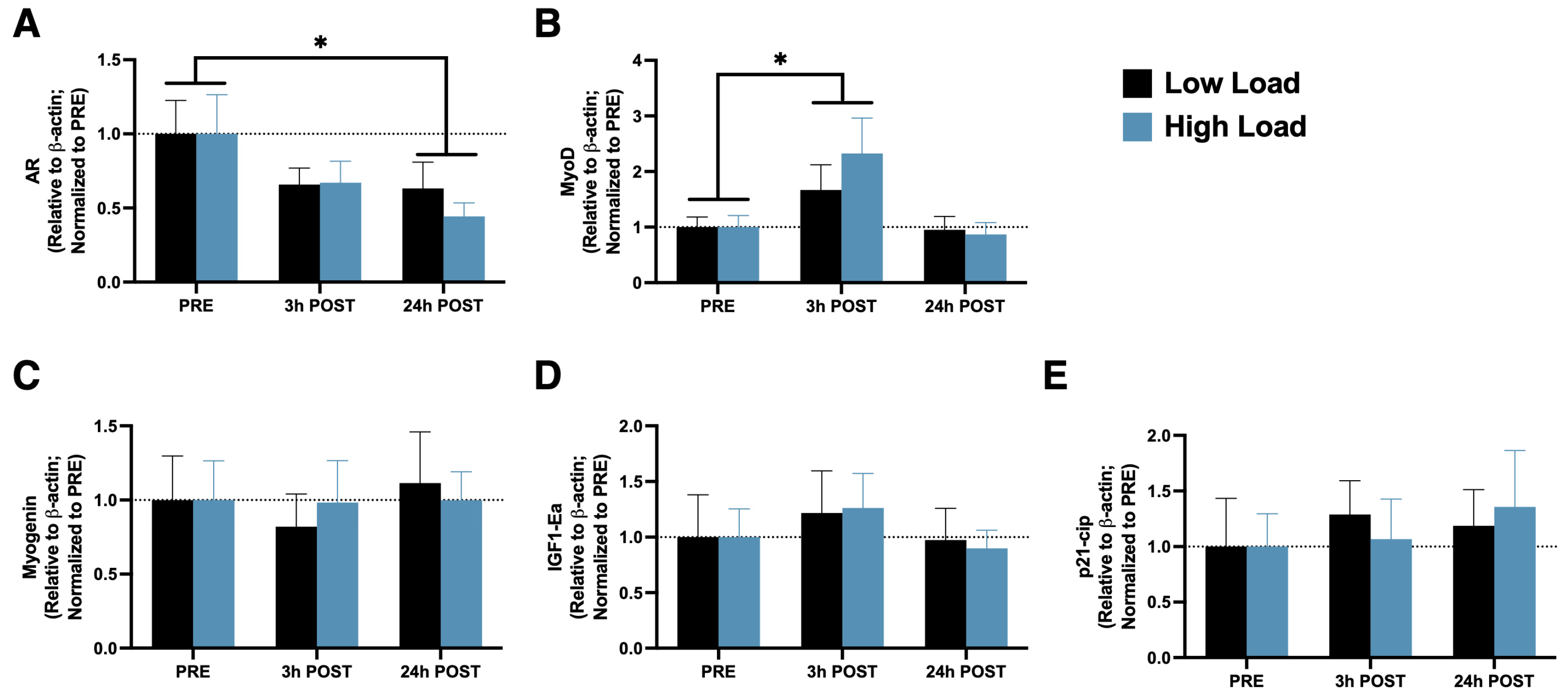

3.1. Gene Expression

3.2. Correlational Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Westcott, W.L. Resistance training is medicine: Effects of strength training on health. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2012, 11, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, A.; Smith, H.K. Unique aspects of competitive weightlifting: Performance, training and physiology. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 769–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratamess, N.; Alvar, B.; Evetoch, T.; Housh, T.; Kibler, W.; Kraemer, W. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults [ACSM position stand]. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 687–708. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, G.E.; Luecke, T.J.; Wendeln, H.K.; Toma, K.; Hagerman, F.C.; Murray, T.F.; Ragg, K.E.; Ratamess, N.A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Staron, R.S. Muscular adaptations in response to three different resistance-training regimens: Specificity of repetition maximum training zones. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 88, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Grgic, J.; Van Every, D.W.; Plotkin, D.L. Loading recommendations for muscle strength, hypertrophy, and local endurance: A re-examination of the repetition continuum. Sports 2021, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, S.; Spaggiari, G.; Barbonetti, A.; Santi, D. Endogenous transient doping: Physical exercise acutely increases testosterone levels-results from a meta-analysis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 43, 1349–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelmann, E.P. Molecular biology of the androgen receptor. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 3001–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.D.; Dalbo, V.J.; Hassell, S.E.; Kerksick, C.M. The expression of androgen-regulated genes before and after a resistance exercise bout in younger and older men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, D.S.; Taylor, L. Effects of sequential bouts of resistance exercise on androgen receptor expression. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denayer, S.; Helsen, C.; Thorrez, L.; Haelens, A.; Claessens, F. The rules of DNA recognition by the androgen receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 898–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bitar, S.; Gali-Muhtasib, H. The role of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21(cip1/waf1) in targeting cancer: Molecular mechanisms and novel therapeutics. Cancers 2019, 11, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenzi, F.; Barberi, L.; Dobrowolny, G.; Villa Nova Bacurau, A.; Nicoletti, C.; Rizzuto, E.; Rosenthal, N.; Scicchitano, B.M.; Musarò, A. Effects of IGF-1 isoforms on muscle growth and sarcopenia. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganassi, M.; Badodi, S.; Wanders, K.; Zammit, P.S.; Hughes, S.M. Myogenin is an essential regulator of adult myofibre growth and muscle stem cell homeostasis. eLife 2020, 9, e60445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardaci, T.D.; Machek, S.B.; Wilburn, D.T.; Heileson, J.L.; Willoughby, D.S. High-load resistance exercise augments androgen receptor-DNA binding and Wnt/β-Catenin signaling without increases in serum/muscle androgens or androgen receptor content. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyward, V.H. The Physical Fitness Specialist Certification Manual; The Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research: Dallas, TX, USA, 1998; Volume 48. [Google Scholar]

- Judelson, D.A.; Maresh, C.M.; Yamamoto, L.M.; Farrell, M.J.; Armstrong, L.E.; Kraemer, W.J.; Volek, J.S.; Spiering, B.A.; Casa, D.J.; Anderson, J.M. Effect of hydration state on resistance exercise-induced endocrine markers of anabolism, catabolism, and metabolism. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 105, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newmire, D.E.; Willoughby, D.S. The skeletal muscle microbiopsy method in exercise and sports science research: A narrative and methodological review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 1550–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machek, S.B.; Harris, D.R.; Zawieja, E.E.; Heileson, J.L.; Wilburn, D.T.; Radziejewska, A.; Chmurzynska, A.; Cholewa, J.M.; Willoughby, D.S. The impacts of combined blood flow restriction training and betaine supplementation on one-leg press muscular endurance, exercise-associated lactate concentrations, serum metabolic biomarkers, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α gene expression. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.J.; Churchward-Venne, T.A.; West, D.W.; Burd, N.A.; Breen, L.; Baker, S.K.; Phillips, S.M. Resistance exercise load does not determine training-mediated hypertrophic gains in young men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 113, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.W.; Oikawa, S.Y.; Wavell, C.G.; Mazara, N.; McGlory, C.; Quadrilatero, J.; Baechler, B.L.; Baker, S.K.; Phillips, S.M. Neither load nor systemic hormones determine resistance training-mediated hypertrophy or strength gains in resistance-trained young men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamman, M.M.; Shipp, J.R.; Jiang, J.; Gower, B.A.; Hunter, G.R.; Goodman, A.; McLafferty, C.L., Jr.; Urban, R.J. Mechanical load increases muscle IGF-I and androgen receptor mRNA concentrations in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 280, E383–E390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diver, M.J.; Imtiaz, K.E.; Ahmad, A.M.; Vora, J.P.; Fraser, W.D. Diurnal rhythms of serum total, free and bioavailable testosterone and of SHBG in middle-aged men compared with those in young men. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003, 58, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintaku, J.; Peterson, J.M.; Talbert, E.E.; Gu, J.M.; Ladner, K.J.; Williams, D.R.; Mousavi, K.; Wang, R.; Sartorelli, V.; Guttridge, D.C. MyoD Regulates Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Metabolism Cooperatively with Alternative NF-κB. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.J.; Fujita, S.; Abe, T.; Dreyer, H.C.; Volpi, E.; Rasmussen, B.B. Human muscle gene expression following resistance exercise and blood flow restriction. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, C.S.; Lee, J.D.; Jackson, J.R.; Kirby, T.J.; Stasko, S.A.; Liu, H.; Dupont-Versteegden, E.E.; McCarthy, J.J.; Peterson, C.A. Regulation of the muscle fiber microenvironment by activated satellite cells during hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1654–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.J.; Conlee, R.K.; Mack, G.W.; Sudweeks, S.; Schaalje, G.B.; Parcell, A.C. Myogenic regulatory factor response to resistance exercise volume in skeletal muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, N.; Pluck, A.; Gurdon, J. MyoD expression in the forming somites is an early response to mesoderm induction in Xenopus embryos. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Peterson, M.D.; Ogborn, D.; Contreras, B.; Sonmez, G.T. Effects of low- vs. high-load resistance training on muscle strength and hypertrophy in well-trained men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2954–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippou, A.; Papageorgiou, E.; Bogdanis, G.; Halapas, A.; Sourla, A.; Maridaki, M.; Pissimissis, N.; Koutsilieris, M. Expression of IGF-1 isoforms after exercise-induced muscle damage in humans: Characterization of the MGF E peptide actions in vitro. In Vivo 2009, 23, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, A.; Joanisse, S.; Moore, D.R.; Bellamy, L.M.; Mitchell, C.J.; Phillips, S.M.; Parise, G. IGF-1 colocalizes with muscle satellite cells following acute exercise in humans. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. Effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 on expression of sensory neuropeptides in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons in the absence or presence of glutamate. Int. J. Neurosci. 2010, 120, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raue, U.; Slivka, D.; Jemiolo, B.; Hollon, C.; Trappe, S. Myogenic gene expression at rest and after a bout of resistance exercise in young (18–30 yr) and old (80–89 yr) women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromaras, K.; Zaras, N.; Stasinaki, A.N.; Mpampoulis, T.; Terzis, G. Lean Body Mass, Muscle Architecture and Powerlifting Performance during Preseason and in Competition. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.; Cardaci, T.; Cintineo, H.; Pham, R.; Dunsmore, K.; Funderburk, L.; Machek, S. A cross-sectional examination of wrist wrap use prevalence and characterization for ergogenic purposes in actively competing powerlifters. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E.E.; Margolis, L.M.; Berryman, C.E.; Lieberman, H.R.; Karl, J.P.; Young, A.J.; Montano, M.A.; Evans, W.J.; Rodriguez, N.R.; Johannsen, N.M.; et al. Testosterone supplementation upregulates androgen receptor expression and translational capacity during severe energy deficit. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 319, E678–E688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, P.; Radaelli, R.; Taaffe, D.R.; Newton, R.U.; Galvão, D.A.; Trajano, G.S.; Teodoro, J.L.; Kraemer, W.J.; Häkkinen, K.; Pinto, R.S. Resistance training load effects on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santanielo, N.; Nóbrega, S.R.; Scarpelli, M.C.; Alvarez, I.F.; Otoboni, G.B.; Pintanel, L.; Libardi, C.A. Effect of resistance training to muscle failure vs non-failure on strength, hypertrophy and muscle architecture in trained individuals. Biol. Sport 2020, 37, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratamess, N.A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Volek, J.S.; Maresh, C.M.; VanHeest, J.L.; Sharman, M.J.; Rubin, M.R.; French, D.N.; Vescovi, J.D.; Silvestre, R.; et al. Androgen receptor content following heavy resistance exercise in men. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 93, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldow, M.K.; Thomas, E.E.; Dale, M.J.; Tomkinson, G.R.; Buckley, J.D.; Cameron-Smith, D. Early myogenic responses to acute exercise before and after resistance training in young men. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Beyer, A.; Aebersold, R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 2016, 165, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, M.V.; Longo, S.; Mallinson, J.; Quinlan, J.I.; Taylor, T.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Narici, M.V. Muscle thickness correlates to muscle cross-sectional area in the assessment of strength training-induced hypertrophy. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilburn, D.; Ismaeel, A.; Machek, S.; Fletcher, E.; Koutakis, P. Shared and distinct mechanisms of skeletal muscle atrophy: A narrative review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Sequence (Forward and Reverse) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| AR | 5′-ATC ATC ACA GCC TGT TGA ACT-3′ 5′-CAA TCC CGA CCC TTC CCA G-3′ | NM_000044.2 |

| MyoD | 5′-CGC CAC CGC CAG GAT ATG-3′ 5′-GTC ATA GAA GTC GTC CGT TGT G-3′ | X56677 |

| Myogenin | 5′-CTG GTG GCA GGA ACA AGC-3′ 5′-GAT GGA CGG ACA GGT GGA G-3′ | NM_002479 |

| IGF-1Ea | 5′-GTG GAT GAG TGC TGC TTC-3′ 5′-GGT TCT GGG TCT TCC TTC-3′ | X57025 |

| p21-cip1 | 5′-CAG CAT GAC AGA TTT CTA CC-3′ 5′-GGA ATC AGA GTC AAA CAC AC-3′ | L25610 |

| β-Actin | 5′-TAA GGA GAA GCT GTG CTA CGT-3′ 5′-AGT TTC GTG GAT GCC ACA GG-3′ | NM_001101 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, B.G.; Cardaci, T.D.; Harris, D.R.; Machek, S.B.; Willoughby, D.S. Skeletal Muscle Androgen-Regulated Gene Expression Following High- and Low-Load Resistance Exercise. DNA 2025, 5, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040056

Costa BG, Cardaci TD, Harris DR, Machek SB, Willoughby DS. Skeletal Muscle Androgen-Regulated Gene Expression Following High- and Low-Load Resistance Exercise. DNA. 2025; 5(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Bailee G., Thomas D. Cardaci, Dillon R. Harris, Steven B. Machek, and Darryn S. Willoughby. 2025. "Skeletal Muscle Androgen-Regulated Gene Expression Following High- and Low-Load Resistance Exercise" DNA 5, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040056

APA StyleCosta, B. G., Cardaci, T. D., Harris, D. R., Machek, S. B., & Willoughby, D. S. (2025). Skeletal Muscle Androgen-Regulated Gene Expression Following High- and Low-Load Resistance Exercise. DNA, 5(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna5040056