Metaverse Tourism: Opportunities, AI-Driven Marketing, and Ethical Challenges in Virtual Travel

Definition

1. Introduction

2. Metaverse as a Digital Extension of Tourism

2.1. Immersive Experiences and Cultural Access

2.2. Economic and Environmental Sustainability

3. Ethical and Societal Implications

3.1. Inclusivity and the Digital Divide

3.2. Privacy and Data Governance

- Real-time, granular consent dashboards;

- Decentralized or self-sovereign identity (SSI) architectures to give users control over disclosure and reuse [33]; and

- Alignment with robust regulatory instruments such as the EU GDPR (2016/679), including rights to erasure, portability, and meaningful human oversight [34].

3.3. Cultural Authenticity and Representation

4. The Role of AI and Personalization

4.1. Hyper Personalisation and Adaptive Storytelling

4.2. Conversational Agents and Emotion AI

4.3. Risks of AI Personalisation: Filter Bubbles, Manipulation, and Bias

4.4. Toward Explainable and Ethical AI

- Transparent recommendation rationales—displaying why particular experiences are surfaced.

- User-controlled preference sliders—letting travellers widen or narrow content diversity.

- Fairness audits and bias impact assessments for datasets and model outputs [46].

- Federated or edge AI to minimise raw data sharing and enhance privacy resilience [47].

5. Future Directions and Responsible Innovation

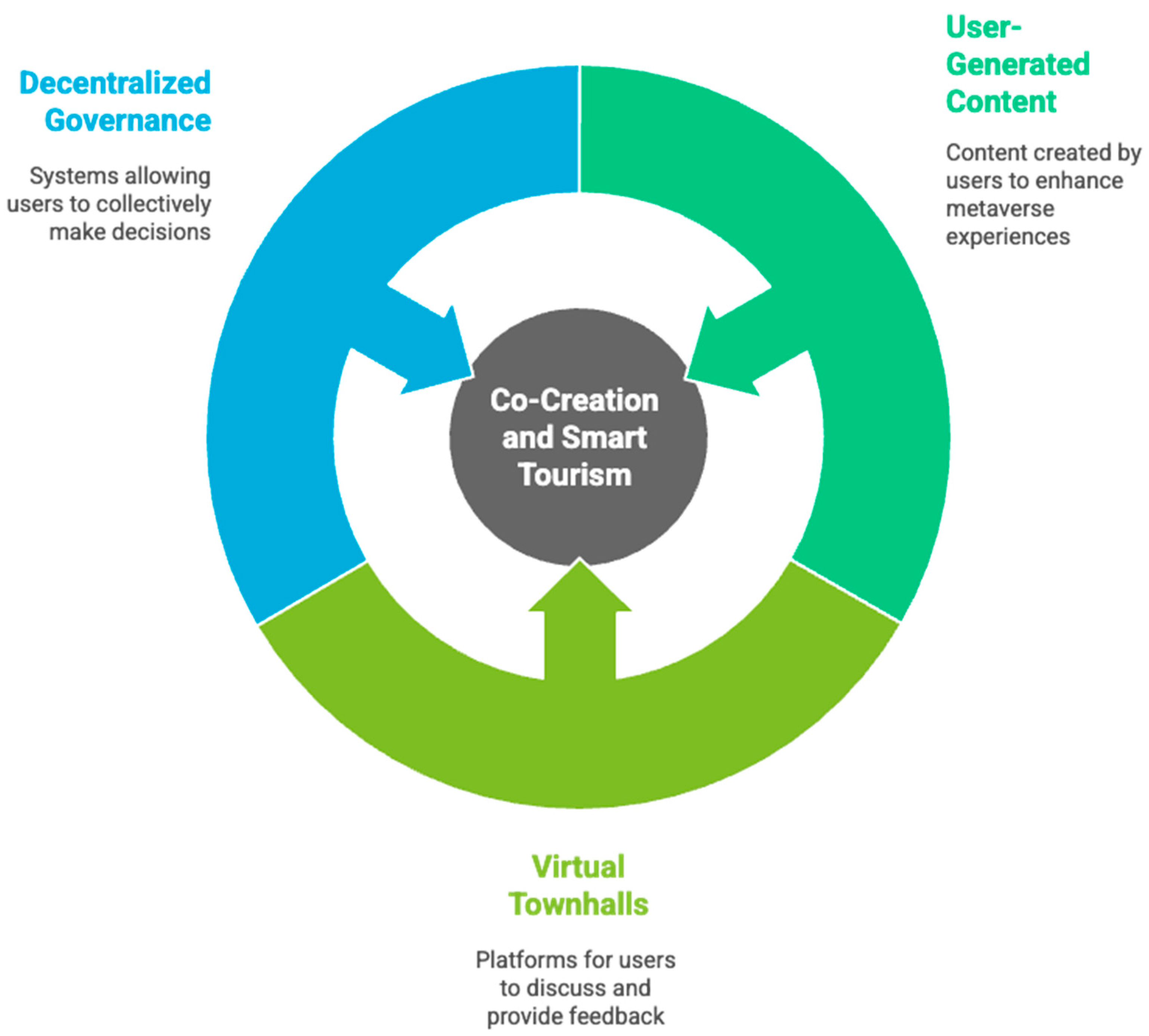

5.1. Smart Tourism and Co-Creation

- User-generated content (UGC) competitions that feed into seasonal VR festivals;

- Tokenised loyalty economies in which visitors earn blockchain-based rewards for contributing 3D assets, translations, or accessibility add-ons [53];

- Living lab “town hall” sessions held inside the metaverse, where locals, designers, and tourists vote—via smart contracts—on future digital twin enhancements [48].

5.2. Ethical Governance and Standards

- Digital tourism charters such as voluntary compacts, signed by platform providers and DMOs, spelling out duties on accessibility, data ethics, cultural integrity, and carbon disclosure [55];

- DAOs that grant token-holding stakeholders proportional voting rights on rule changes, revenue allocation, and moderation appeals, thereby fostering community self-governance [56];

- Third-party certification labels, akin to ISO management standards, that audit virtual experience safety, authenticity, and disability compliance before public release [57].

- Ensure GDPR compliance and data minimization: Immersive environments collect vast biometric and behavioral data. GDPR compliance ensures user trust, while minimization prevents unnecessary data harvesting. Without it, platforms risk legal penalties and reputational damage.

- Provide transparent AI explanations: Explainable AI builds user confidence in recommendations and pricing. Tourists should know why certain experiences are suggested, avoiding hidden biases or manipulation.

- Adopt renewable energy in server farms: VR/AR rendering and blockchain consume enormous energy. Shifting server infrastructure to renewables reduces carbon footprints and aligns metaverse tourism with sustainability goals.

- Include accessibility features for disabled and elderly travellers: Features like voice commands, haptic feedback, subtitles, and simplified interfaces expand participation. Accessibility ensures inclusivity and compliance with global tourism ethics.

- Avoid over-commercialization of heritage: Virtual heritage risks commodification if driven solely by profit. Safeguards must prevent sacred or cultural assets from being trivialized or distorted for entertainment.

- Engage local communities in co-creation: Involving locals ensures authenticity, equitable benefit-sharing, and protection against digital colonialism. It also builds community ownership of virtual destinations.

- Monitor NFT/blockchain sustainability: NFT-based ticketing or souvenirs carry risks of speculation and high energy costs. Monitoring ensures financial fairness and ecological responsibility.

- Develop moderation crisis protocols: Virtual worlds face risks of harassment, misinformation, or cultural misrepresentation. Platforms need clear moderation strategies to address crises quickly and fairly.

- Implement diversity/bias audits in recommender systems: AI-driven recommendations can marginalise minority cultures or reinforce stereotypes. Regular audits ensure cultural diversity and fairness in content exposure.

- Provide low-bandwidth XR modes for inclusion: Many users in developing regions lack high-speed internet or costly headsets. Lightweight, mobile-first XR versions broaden access and prevent digital divides.

- Link KPIs with UN SDGs: Aligning key performance indicators (KPIs) with the UN Sustainable Development Goals makes virtual tourism measurable against global sustainability standards (SDG 12 Responsible Consumption).

- Establish continuous governance feedback: Tourism platforms evolve rapidly. Feedback loops (DAO voting, community surveys) allow adaptive governance, ensuring that ethical principles keep pace with technological changes.

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

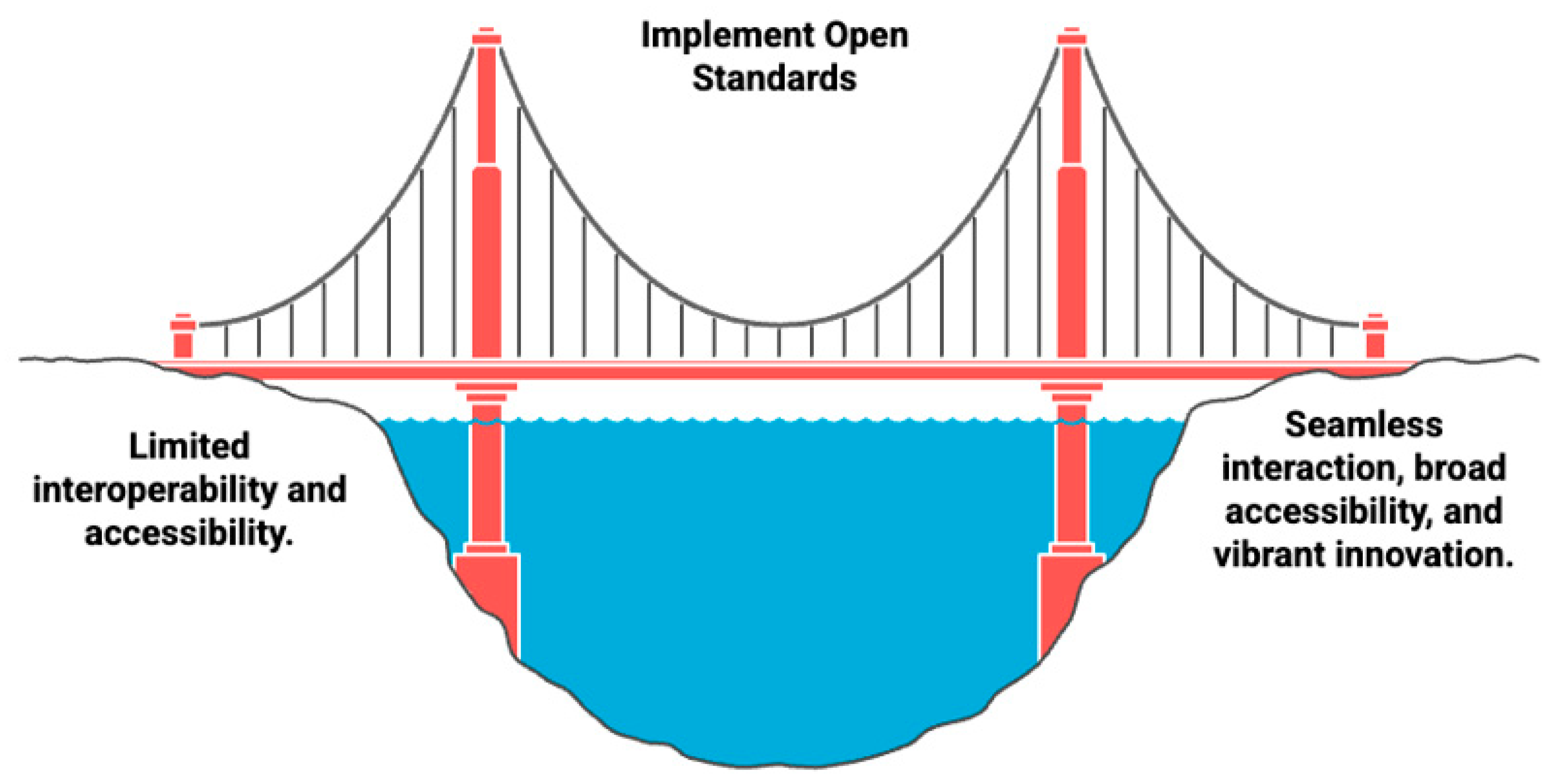

- Interoperability and open standards to prevent walled gardens and enable seamless tourist mobility across platforms [62].

- Ethics by design frameworks that integrate privacy-preserving computation, bias audits, and community consultation at every development stage [63].

- Inclusive infrastructure strategies, subsidised device programmes, low bandwidth XR modes, and digital literacy initiatives to ensure broad participation [28].

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| COVID−19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| NFTs | Non-Fungible Tokens |

| SMEs | Small Medium Enterprises |

| GPU | Graphic Processing Units |

| SSI | Self-Sovereign Identity |

| EU GDPR | European Union General Data Protection Regulation |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

| NPCs | Non-Player Characters |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| DAOs | Decentralized Autonomous Organizations |

| DMOs | Destination Management Organizations |

| UGC | User-Generated Content |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| UN SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| IP | Internet Protocol |

References

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, D.L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Giannakis, M.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Wamba, S.F. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Tripathi, P. Bibliometric insight into metaverse’s role in the tourism industry. Int. J. Tourism Hotel Manag. 2024, 6, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, S.; Farooq, S.; Reshi, M. Tourism, the metaverse, artificial intelligence, and travel. J. Soc. Responsib. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 26, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, K.; Sharma, B.; Khatwani, R.; Mishra, M.; Mitra, P.K. Impact of metaverse technology on hospitality and tourism industry: An interplay of social media marketing on hotel booking in India. Int. J. Tourism Cities 2024, 10, 1533–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Ricci, P. The new era of hotel marketing: Integrating cutting-edge technologies with core marketing principles. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2024, 15, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, H.B.; Wang, J.-C.; Windasari, N.A. Impact of multisensory extended reality on tourism experience journey. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 356–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Saleh, M.I. Tourism metaverse from the attribution theory lens: A metaverse behavioral map and future directions. Tour Rev. 2024, 79, 1088–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrifan, A. Foundational concepts of AI and the metaverse in tourism: A scholarly inquiry. In AI–Driven Metaverse Applications in Tourism and Hospitality Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, H.; Kang, M. Metaverse tourism for sustainable tourism development: Tourism Agenda 2030. Tourism Rev. 2022, 78, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, A.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Ye, H.; Lei, S. Ethical artificial intelligence (AI): Principles and practices. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Koo, I.; Abbasi, S.; Raza, S.H.; Qureshi, M.G. Meet your digital twin in space? Profiling international expat’s readiness for metaverse space travel, tech-savviness, COVID-19 travel anxiety, and travel fear of missing out. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.A. Virtual reality: Applications and implications for tourism. Tourism Manag. 2010, 31, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Ali, F.; Abdalla, M.J.; Alotaibi, S. Beyond the hype: Evaluating the impact of generative AI on brand authenticity, image, and consumer behavior in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 131, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersüren, S.; Özel, Ç.H. The effect of virtual reality experience quality on destination visit intention and virtual reality travel intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2024, 15, 70–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, M.; Morrison, A.M. Semiotic analysis of metaverse digital humans and cultural communication. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Khan, U.; Khan, K.A. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing: Exploring Perceptions, Risks, and Benefits from a Managerial Standpoint. ICHRIE Res. Rep. 2025, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvre Museum. Visit the Louvre Online. 2021. Available online: https://www.louvre.fr/en/visites-en-ligne (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Mihalič, T. Metaversal sustainability: Conceptualisation within the sustainable tourism paradigm. Tourism. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, S.; Kaya, B.; Altıntaş, V. From America to Anatolia: A Perspective on Oenotourism within the Context of Sustainable Practices and Applications. Millenium J. Educ. Technol. Health. 2025, 2, e41106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengoz, A.; Cavusoglu, M.; Kement, U.; Bayar, S.B. Unveiling the symphony of experience: Exploring flow, inspiration, and revisit intentions among music festival attendees within the SOR model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandali, D.; Raza, M. The emergence of artificial intelligence-driven reservation services analyzed through push-pull-mooring theory and their potential to enhance tourism experiences. J. Glob. Hosp. Tour. 2025, 4, 10–28. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/jght/vol4/iss1/2/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Gajdošík, T.; Orelová, A. Smart Technologies for Smart Tourism Development. In Artificial Intelligence and Bioinspired Computational Methods; Silhavy, R., Ed.; CSOC 2020; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. How to stop data centres from gobbling up the world’s electricity. Nature 2018, 561, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M. The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media. Soc. 2019, 21, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kement, U.; Dogan, S.; Bayar, S.B.; Bayram, G.E.; Basar, B.; Cobanoglu, C. The effect of self-service technology quality on novelty-seeking and revisit intention in restaurant settings. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2025, 27, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Technology and Innovation Report. 2021: Catching Technological Waves; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tir2020_en.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- World Bank. World Development Report 2016: Digital. Dividends; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, M. What Is the Metaverse? An Explanation and In-Depth Guide. TechTarget. 2023. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/The-metaverse-explained-Everything-you-need-to-know (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J.; Beltrametti, M.; Chatila, R.; Chazerand, P.; Dignum, V.; Luetge, C.; Madelin, R.; Pagallo, U.; Rossi, F.; et al. AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds. Mach. 2018, 28, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raji, I.D.; Smart, A.; White, R.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Smith-Loud, J.; Theron, D.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. FAT. ’20 Proc. Conf. Fairn. Account. Transpar. 2020, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.U. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sporny, M.; Longley, D.; Chadwick, D. Decentralized. Identifiers. (DIDs.) v1.0; W3C Recommendation, 2022; Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/did-core/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation—GDPR). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L119, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C.J. Reconceptualising Interpretation: The Role of Tour Guides in Authentic Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanelli, R. Unpopular culture: Ecological dissonance and sustainable futures in media-induced tourism. J. Pop. Cult. 2019, 52, 1250–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandalis, K.S.; Ghazzawi, I.A. The effect of transformational leadership on employee engagement in the hospitality and tourism industry in Greece. Glob. J. Entrep. (GJE) 2024, 8, 34–2574. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, L.; Ning, K. Minority tourist information service and sustainable development of tourism under the background of smart city. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 6547186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Li, Y.; Song, H. ChatGPT and the hospitality and tourism industry: An overview of current trends and future research directions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Nanu, L.; Cavusoglu, M.; Sepe, F.; Alotaibi, S. Hotel App Quality (HAPQUAL): Conceptualization and scale development. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 2094–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, K.; Zafer, K.S.; Erul, E. Bibliometric analysis of GIS-based tourism research: Trends, topics, and future directions in terms of sustainable tourism management. SAGE Open 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hall, C.M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Exploring the impact of Virtual Reality on tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors in heritage tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B.D.; Allo, P.; Taddeo, M.; Wachter, S.; Floridi, L. The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkiopoulos, C.; Gkintoni, E. The role of machine learning in AR/VR-based cognitive therapies: A systematic review for mental health disorders. Electronics 2025, 14, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. A review of research into automation in tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on artificial intelligence and robotics in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandali, D.; Magoutas, A.; Tsourvakas, G. Consumer behaviour analysis for AI services in the tourism industry. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2024, 32, 332–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulung, L.E.; Lapian, S.L.H.V.J.; Lengkong, V.P.K.; Tielung, M.V.J. The role of smart tourism technologies, destination image and memorable tourism experiences as determinants of tourist loyalty. Rev. Gest. Soc. Ambient. 2025, 19, e011822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Beyond boundaries: Exploring the metaverse in tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 37, 1257–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basirati, M.; Laachach, A. Clustering sustainable tourism destinations through Instagram photo analysis: A machine learning approach. Tour Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesliokuyucu, O.S.; Cobanoglu, C. The Implications of Gamification in Tourism; Tourism on the Verge; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Sesliokuyucu, O.S.; Khan, K.A.; Alotaibi, S.; Wu, C. The impact of robotic gastronomic experiences on customer value, delight and loyalty in service-robot restaurants. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 8053–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, G.; Chatzipanagiotou, K.; Baker, J.; Buhalis, D. Conceptualizing and measuring customer luxury experience in hotels. J. Travel Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippi, P.; Mannan, M.; Reijers, W. Blockchain as a confidence machine: The problem of trust & challenges of governance. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Code of Ethics for Tourism. Uclg-mewa.org n.d. Available online: https://uclg-mewa.org/en/global-code-of-ethics-for-tourism/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Rodriguez-Garcia, B.; Guillen-Sanz, H.; Checa, D.; Bustillo, A. A systematic review of virtual 3D reconstructions of Cultural Heritage in immersive Virtual Reality. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 89743–89793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO TC 324; Virtual Tourism Services—Quality, Safety and Accessibility Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, R. Smart hospitality—Interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandali, D. Social media ethics: Balancing transparency, AI marketing, and misinformation. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Ersoy, A.; Lodhi, R.N.; Cobanoglu, C. Mapping the metaverse-sustainability nexus in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric approach. Online. Inf. Rev. 2025, 49, 600–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Antonopoulou, H.; Sortwell, A.; Halkiopoulos, C. Challenging Cognitive Load Theory: The role of Educational Neuroscience and Artificial Intelligence in redefining Learning Efficacy. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarezadeh, Z.Z.; Rastegar, R.; Xiang, Z. Big data analytics and hotel guest experience: A critical analysis of the literature. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2320–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prillard, O.; Boletsis, C.; Tokas, S. Ethical Design for Data Privacy and User Privacy Awareness in the Metaverse. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Roma, Italy, 26–28 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu, R.I.; Bodislav, D.A. The workplace dynamic of people-pleasing: Understanding its effects on productivity and well-being. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skandali, D. Metaverse Tourism: Opportunities, AI-Driven Marketing, and Ethical Challenges in Virtual Travel. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030135

Skandali D. Metaverse Tourism: Opportunities, AI-Driven Marketing, and Ethical Challenges in Virtual Travel. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(3):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030135

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkandali, Dimitra. 2025. "Metaverse Tourism: Opportunities, AI-Driven Marketing, and Ethical Challenges in Virtual Travel" Encyclopedia 5, no. 3: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030135

APA StyleSkandali, D. (2025). Metaverse Tourism: Opportunities, AI-Driven Marketing, and Ethical Challenges in Virtual Travel. Encyclopedia, 5(3), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030135