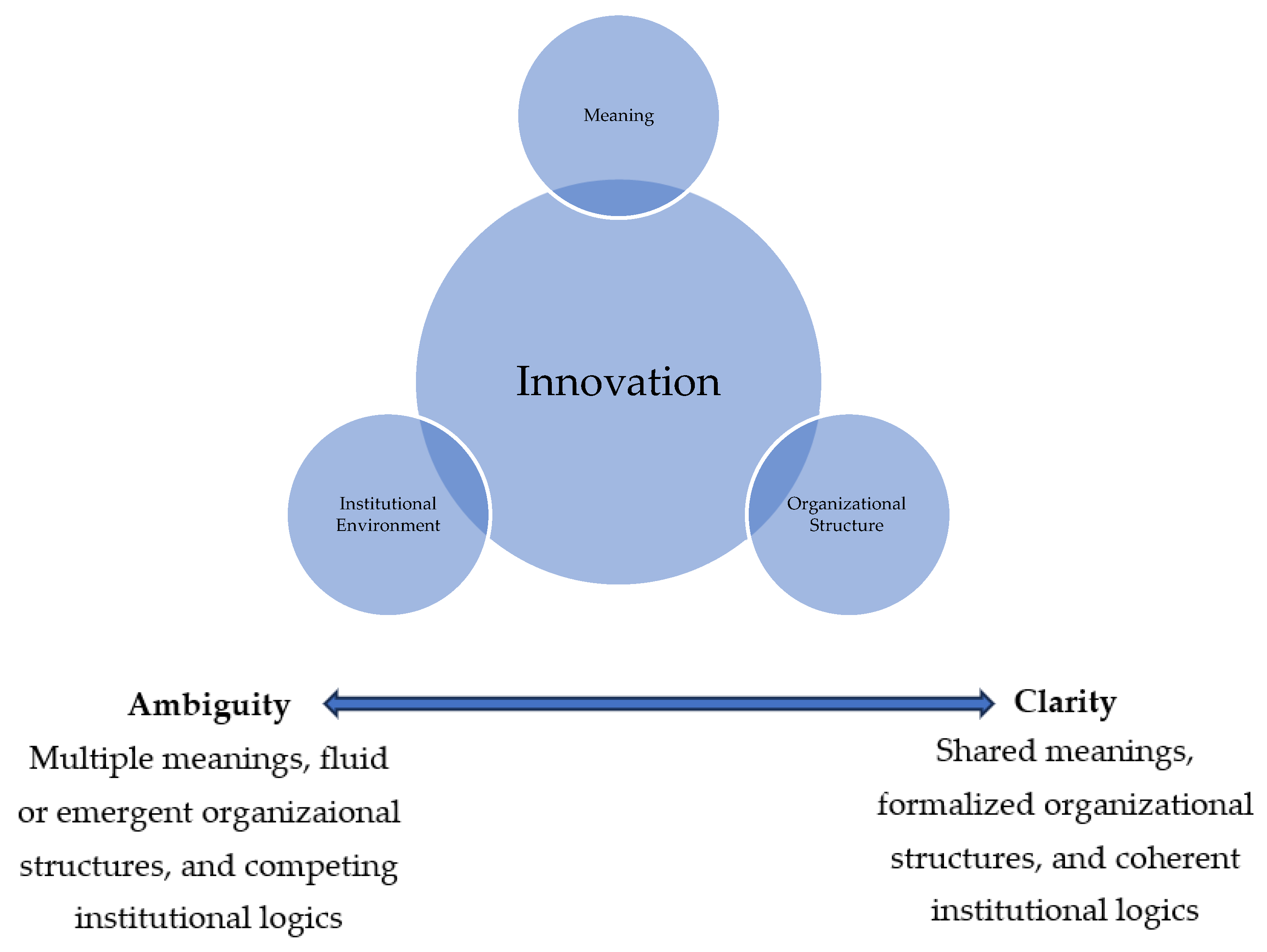

Innovation: Between Ambiguity and Clarity

Definition

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizations, Definitions, and Typologies of Innovation

- Linear and closed innovation (World War I to mid-1980s): A sequential, internal process ending in market delivery, based on the assumption that innovation occurs within organizational boundaries [11] (p. 35).

- Interactive and closed innovation (mid-1980s–2000s): Innovation is understood as an interactive process dependent on internal collaboration. This model emphasizes the role of organizational infrastructure in facilitating knowledge exchange: “what matters is the internal capacity of organizations to facilitate the interactions between actors…to reinforce innovative ideas” [11] (p. 39).

- Interactive and open innovation (2000s–present): Inspired by Chesbrough’s (2006) [37] open innovation model, this approach posits that organizations innovate by leveraging internal and external knowledge sources—such as customers, universities, and startups—using both pecuniary and nonpecuniary mechanisms [38].

2.2. Perspectives of Innovation

2.2.1. Institutional Perspective

2.2.2. Process Perspective

2.2.3. Innovation Management

2.3. Innovation and Complexity

3. Ambiguity and Clarity: A Configurational View

Variation Across Innovation Types

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Prospects for Future Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leifer, R.; O’Connor, G.C.; Rice, M. Implementing radical innovation in mature firms: The role of hubs. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2001, 15, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüsay, A.A.; Reinecke, J. Imagining desirable futures: A call for prospective theorizing with speculative rigour. Organ. Theory 2024, 5, 26317877241235939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, H.; Goduscheit, R.C.; Schweisfurth, T.; Visser-Groeneveld, J. The role of creativity and innovation in the quality of our lives, the planet and science. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2024, 34, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Richou, S.; Chizallet, M.; Lubart, T. Future-Oriented Thinking: The Creativity Connection. In Transformational Creativity: Learning for a Better Future; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.; Potočnik, K.; Zhou, J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H. The innovation journey: You can’t control it, but you can learn to maneuver it. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2017, 19, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Tuertscher, P.; Van de Ven, A.H. Perspectives on innovation processes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 775–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetrati, M.; Hansen, D.; Akhavan, P. How to manage creativity in organizations: Connecting the literature on organizational creativity through bibliometric research. Technovation 2022, 115, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, D.; David, R.J.; Akhlaghpour, S. Coevolution in management fashion: An agent based model of consultant-driven innovation. Am. J. Sociol. 2014, 120, 226–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohendet, P.; Simon, L. Concepts and models of innovation. In The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation; Antonelli, C., Link, A.N., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, M.J.; Naughton, B.D.; Field, M.; Shaw, S.E. Perceptions of impure innovation: Health professionals’ experiences and management of stigmatization when working as digital innovators. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 360, 117301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kochetkov, D.M. Innovation: A state-of-the-art review and typology. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2023, 7, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M.; Crumley, E.T. New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.L.; Rittblat, R. Facilitating Innovation for Complex Societal Challenges: Creating Communities and Innovation Ecosystems for SDG Goal of Forming Partnerships. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckwitz, A. The Society of Singularities; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, M.A.; Brem, A. What innovation managers really do: A multiple-case investigation into the informal role profiles of innovation managers. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 1055–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittblat, R.; Oliver, A.L. Ambiguous zones and identity processes of innovation experts in organizations. In Organizing Creativity in the Innovation Journey; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; Volume 75, pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Hamel, G.; Mol, M.J. Management innovation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Erez, M.; Jarvenpaa, S.; Lewis, M.W.; Tracey, P. Adding complexity to theories of paradox, tensions, and dualities of innovation and change: Introduction to organization studies special issue on paradox, tensions, and dualities of innovation and change. Organ. Stud. 2017, 38, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, H.; Cohendet, P.; Henn, S.; Simon, L. Innovation and Knowledge Creation: Challenges to the Field; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, L.; Walters, H.; Pikkel, R.; Quinn, B. Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mahringer, C.A. Innovating as chains of interrelated situations. Scand. J. Manag. 2024, 40, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampa, R.; Agogué, M. Developing radical innovation capabilities: Exploring the effects of training employees for creativity and innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kars-Unluoglu, S. How do we educate future innovation managers? Insights on innovation education in MBA syllabi. Innov. Manag. Policy Pract. 2016, 18, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, E.; Rodriguez-Prado, B. Building ambidexterity through creativity mechanisms: Contextual drivers of innovation success. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.; Höllerer, M.A.; Seidl, D. What theory is and can be: Forms of theorizing in organizational scholarship. Organ. Theory 2021, 2, 26317877211020328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnari, S.; Crilly, D.; Misangyi, V.F.; Greckhamer, T.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Capturing causal complexity: Heuristics for configurational theorizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 778–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüsay, A.A.; Amis, J.M. Contextual expertise and the development of organization and management theory. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2021, 18, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splitter, V.; Dobusch, L.; von Krogh, G.; Whittington, R.; Walgenbach, P. Openness as organizing principle: Introduction to the special issue. Organ. Stud. 2023, 44, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly III, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest and the Business Cycle, reprint ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Velu, C.; Jacob, A. Business model innovation and owner–managers: The moderating role of competition. R&D Manag. 2014, 46, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, R.K.; Prabhu, J.C. Innovation typologies. In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing; Sheth, J., Malhotra, N., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Part 5: Product Innovation and Management. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. The era of open innovation. Manag. Innov. Chang. 2006, 12, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sundbo, J. The Theory of Innovation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrand, O.; Holgersson, M. Innovation ecosystems: A conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation 2020, 90, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehman, J.; Lounsbury, M.; Greenwood, R. How institutions matter: From the micro foundations of institutional impacts to the macro consequences of institutional arrangements. In How Institutions Matter! Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 48, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kostova, T.; Beugelsdijk, S.; Scott, W.R.; Kunst, V.E.; Chua, C.H.; van Essen, M. The construct of institutional distance through the lens of different institutional perspectives: Review, analysis, and recommendations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 467–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.C.; Santos, F. When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour, F.; Schneider, M. Phases of the adoption of innovation in organizations: Effects of environment, organization and top managers. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.B.; Suddaby, R. Institutions and institutional work. In Handbook of Organization Studies, 2nd ed.; Clegg, R., Hardy, C., Lawrence, T.B., Nord, W.R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, N. Organizing innovation. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 482–505. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, T.; Hinings, C.R. Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W. Institutional logics. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Sage: London, UK, 2008; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury, M.; Steele, C.W.; Wang, M.S.; Toubiana, M. New directions in the study of institutional logics: From tools to phenomena. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Gehman, J.; Giuliani, A. Contextualizing entrepreneurial innovation. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Back, Y.; Parboteeah, K.P.; Nam, D.I. Innovation in emerging markets: The role of management consulting firms. J. Int. Manag. 2014, 20, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtka, J.M.; Salzman, R.; Azer, D. Democratizing innovation in organizations: Teaching design thinking to non-designers. Des. Manag. Rev. 2017, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puech, L.; Durand, T. Classification of time spent in the intrapreneurial process. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, A.; Bechky, B. When collections of creatives become creative collectives: A field study of problem solving at work. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D. Innovation in the practice perspective. In The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, B. A fantasy theme analysis of three guru-led management fashions. In Critical Consulting; Clark, T., Fincham, R., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 172–190. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson, E.; Eisenman, M. Employee-management techniques: Transient fads or trending fashions? Adm. Sci. Q. 2008, 53, 719–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, M.A.; D’Aunno, T. An intellectual history of institutional theory: Looking back to move forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2023, 17, 301–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, G.S.; Oliver, A.L. Innovation and entrepreneurship in the start-up nation: Sociological perspectives. Israeli Sociol. 2021, 2, 6–13. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- ISO 56002:2019; Innovation Management System: Guidance. ISO—The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:56002:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Adams, R.; Bessant, J.; Phelps, R. Innovation management measurement: A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattström, A.; Frishammar, J.; Richtner, A.; Pflueger, D. Can innovation be measured? A framework of how measurement of innovation engages attention in firms. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2018, 48, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, E.C. The sociology of innovation: Organizational, environmental, and relative perspectives. Sociol. Compass. 2014, 8, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Drori, G.S. Creativity and the governance of universities: Encounters of the third kind. Eur. Rev. 2018, 26, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupp, M.; Anderson, J.; Reckhenrich, J. Why design thinking in business needs a rethink. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Miron-Spektor, E.; Erez, M.; Naveh, E. The effect of conformist and attentive-to-detail members on team innovation: Reconciling the innovation paradox. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 740–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, A.B.; Douglas, Y. When innovations meet institutions: Edison and the design of the electric light. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 476–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H.; Polley, D.E.; Garud, R.; Venkataraman, S. Building an infrastructure for the innovation journey. In The Innovation Journey; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 149–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 82, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. The process of social innovation. Innovations 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Typology | Meaning Configuration | Organizational Structure | Institutional Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear & Closed | Innovation as step-by-step delivery of technical solutions | Sequential, internal process | Stable, efficiency-oriented institutions |

| Interactive & Closed | Innovation as internal recombination of knowledge | Infrastructure for collaboration and knowledge sharing | Relatively closed field emphasizing internal capacity |

| Interactive and open | Innovation as co-creation across boundaries | Internal and external actors networks | Co-existence of multiple actors (public, private, academia) |

| Social Innovation | Innovation as a social construction of public value | Often hybrid (e.g., partnerships, nonprofits) | Multiple, contested logics |

| Cultural Innovation | Innovation as symbolic transformation; reframing values and shared meaning | Loosely structured collectives or individuals | Normative, discursive environments |

| Technological Innovation | Innovation as technical solutions to defined needs | Often pipeline-based, but can involve open R&D | Regulated by scientific or commercial standards |

| Managerial Innovation | Innovation as restructuring work practices and new routines | Experimental then routinized | Driven by consultancy models or professional norms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rittblat, R. Innovation: Between Ambiguity and Clarity. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030123

Rittblat R. Innovation: Between Ambiguity and Clarity. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(3):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030123

Chicago/Turabian StyleRittblat, Rotem. 2025. "Innovation: Between Ambiguity and Clarity" Encyclopedia 5, no. 3: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030123

APA StyleRittblat, R. (2025). Innovation: Between Ambiguity and Clarity. Encyclopedia, 5(3), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5030123