Definition

For the purposes of this entry, special educational needs (SEN) refers to a condition where a student requires additional support to access education due to a disability, learning difficulty, or other developmental challenges. In this entry, an overview is provided of the prevalence of and categories of SEN in Irish-immersion primary and post-primary schools across the island of Ireland. This entry examines the prevalence and categories of SEN in Irish-immersion (IM) primary and post-primary schools across the island of Ireland. With immersion education playing a significant role in fostering bilingual proficiency, understanding SEN prevalence within these settings is critical for ensuring inclusive educational practices. The entry analyses trends over the past two decades in SEN prevalence, highlighting an increase in SEN identification, particularly in IM post-primary schools. It also explores regional disparities, comparing Gaeltacht and IM schools outside of the Gaeltacht, as well as differences between IM and English-medium education sectors. Factors such as socio-economic disadvantage, diagnostic advancements, and policy developments are considered when interpreting SEN trends. The findings contribute to the limited international research on SEN prevalence in immersion education and offer insights into recommendations in the areas of policy and practice to further support students with diverse learning needs in bilingual settings.

1. Context

Over the last 50 years, Irish-immersion (IM) education has experienced remarkable growth in both the Republic of Ireland (RoI) and Northern Ireland (NI). The aim of this form of education is for students to gain proficiency in the national or heritage language, Irish, at no cost to their first language development [1,2,3]. IM schools can be located in Gaeltacht areas or outside of the Gaeltacht. In these schools, all curriculum subjects are taught through the medium of Irish, except for English and modern foreign languages [4]. It has been found that most students attending IM schools outside of the Gaeltacht come from homes where English is their home language [5,6]. The Gaeltacht refers to regions in Ireland where the Irish language is the primary spoken language of daily life [7]. These areas are mostly located along the western seaboard in counties such as Donegal, Mayo, Galway, and Kerry, as well as smaller areas in counties Cork, Meath, and Waterford. Recent census data, however, suggest that there has been an increase in cultural and linguistic diversity in these schools over time and that now only 66% (n = 65,156) of the Gaeltacht population speak Irish [8].

In the early 1970s, there were only a handful of IM schools outside the Gaeltacht, but by 2024, this number had grown to 256 IM primary schools. The total number of students in IM primary and post-primary education has now surpassed 66,000. In NI, the sector has expanded significantly from fewer than 500 students in the early 1980s to over 7000 in 2024 [5,6]. This increase represents a broader shift towards bilingual education, supported by language planning initiatives, government policies, and research highlighting the cognitive and linguistic benefits of immersion education [1,2,3]. The rapid growth of IM education reflects both a societal push to revitalise the Irish language and a growing recognition of the advantages of bilingual learning [9].

At present there are 153 IM primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht and there are 103 within the Gaeltacht areas [10]. There are also 35 IM primary schools in NI (see Table 1). The total estimated number of students enrolled in these schools is 48,684. Outside of the Gaeltacht in the RoI, there are 47 IM post-primary schools, and an estimated 11,951 students enrolled. There are five IM post-primary schools in Northern Ireland with 1675 students enrolled. There were 29 Gaeltacht post-primary schools with approximately 3832 students enrolled.

Table 1.

The number of Gaeltacht and IM primary and post-primary schools and student enrolment figures. Data from [10].

This entry provides a discussion and analysis of the prevalence and categories of SEN in these schools across the island of Ireland from articles published in peer review journals and funded reports. In the RoI, this data includes IM schools in Gaeltacht areas and outside of the Gaeltacht. It provides a discussion and analysis of the trends in SEN prevalence over the past two decades in IM primary and post-primary schools. The regional disparities, for example, comparing Gaeltacht and IM schools outside of the Gaeltacht, as well as differences between IM and English-medium education sectors are discussed. Following this, recommendations are made for future special education provision in these schools in the areas of policy and practice. The overview provided may be of interest to immersion education contexts internationally, as limited statistical information on SEN prevalence for immersion education contexts is available internationally.

1.1. Special Educational Needs

For the purposes of this entry, SEN refers to a condition where a student requires additional support to access education due to a disability, learning difficulty, or other developmental challenges [11]. The Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act 2004 [11] defines SEN as a “restriction in capacity to participate in and benefit from education” due to an enduring physical, sensory, mental health, intellectual, or learning disability. SEN can include a wide range of needs, such as dyslexia, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD), and speech and language disorders. In schools in the RoI and NI, support for students with SEN is provided through additional teaching resources, special education teachers, special needs assistants/classroom assistants and access to specialised assessments and interventions [11,12].

1.2. Mainstream Schools, Special Classes, and Special Schools

The Irish education system aims to provide an inclusive model, ensuring that children with SEN can participate fully in mainstream or special education settings, depending on their needs [13,14,15,16]. The inclusive model of education in the RoI aims to ensure that students with SEN can access quality education alongside their peers in mainstream schools whenever possible. This approach aligns with the EPSEN Act 2004 [11], which promotes the right of children with SEN to be educated in mainstream settings with appropriate support where possible. In NI, the education system also focuses on educating all students, including those with SEN and disabilities, in mainstream educational settings where appropriate [13]. This approach is grounded in various legislative frameworks and policies aimed at promoting equality and accessibility within the education system [17].

In both the RoI and NI, students can be educated in mainstream schools, special classes attached to mainstream schools, or special schools based on their needs [18,19]. In mainstream schools, students with SEN are typically educated in classes with their peers and access additional support such as additional teaching support, a special needs assistant/classroom assistant, or assistive technology. Special classes for students with a range of diagnoses, have a lower student-teacher ratio and have access to special needs assistants/classroom assistants in the classroom. A small number of IM schools have special classes, with only 2 IM schools in NI and 33 schools in the RoI with these classes [20]. In both the RoI and NI, there are no special classes available through the medium of Irish for students with a diagnosis of specific speech and language delay or dyslexia [21,22]. More funding should be made available by the government to allow special classes for students with these SEN to open in IM schools; this funding should cover premises, teaching resources and teacher education. It is important that the practices in place in these classes would consider the nuances of SEN and bilingualism/immersion education. In the special classes available in English-medium schools, students are often exempt from the study of Irish due to their learning difficulties [23]. When there are no places available in a special class or special school, it is recommended that children attend a mainstream setting and receive additional teaching support there [21,22]. Special schools provide education to children and young people from age 4 to 18 with a range of SEN and they deliver both the primary and post-primary school curriculum [24]. In the RoI there is one IM special school located in a Gaeltacht area. Unfortunately, in NI, there are no IM special schools.

1.3. Primary and Post-Primary Education in the Republic of Ireland

Primary education in the RoI is designed to provide a broad and balanced curriculum for children aged approximately 4 to 12 years. It consists of an eight-year cycle, including junior (age 4–5) and senior infants (age 5–6) followed by six class levels [25,26]. The curriculum, set by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA), emphasises literacy, numeracy, social, and personal development, alongside subjects such as science, geography, history, and the arts [27].

Post-primary education in the RoI typically begins at the age of 12 and continues until the age of 18 [25,26,27]. It is divided into two cycles: Junior Cycle and Senior Cycle. Junior Cycle education typically lasts for three years, from the ages of 12 to 15. Its main aim is to provide students with a broad, balanced curriculum [28]. There is a focus on the development of key skills such as communicating, teamwork, and problem-solving. Following completion of the Junior Cycle and the Junior Certificate Examination, and before commencing the two-year Senior Cycle (typically at age 15/16), some students undertake Transition Year [29]. This is an optional one-year programme in the Irish education system designed to provide students with an opportunity to experience a broad range of subjects and activities outside the regular curriculum that promote personal, social, vocational, and educational development. The Senior Cycle in Irish post-primary schools typically lasts for two years, usually from the ages of 15/16 to 17/18 years old [28]. Most students at Senior Cycle level take the Leaving Certificate Examination, usually at the age of 17–18.

1.4. Primary and Post-Primary Education in Northern Ireland (NI)

The primary education system in NI is structured to provide foundational education for children aged 4 to 11 [30]. It is divided into seven-year groups, from Primary 1 (P1, age 5) to Primary 7 (P7, age 11). The Northern Ireland Curriculum [31] encompasses the following topics: language and literacy (English and Irish in IM schools), mathematics, science, geography, history, personal development and mutual understanding, the arts (music, drama, art), physical education, and religious education (often aligned with the school’s ethos).

Post-primary education in NI typically begins at the age of 11 and continues until the age of 16 or 18 [32,33]. It is divided into two key stages: Key Stage 3 (KS3) and Key Stage 4 (KS4) [33]. Key Stage 3 covers ages 11 to 14 and is roughly the equivalent to the Junior Cycle in post-primary education in the RoI. Key Stage 4 covers ages 14 to 16 and is roughly equivalent to the Senior Cycle in post-primary education in the RoI. The curriculum at Key Stage 3 is broad and balanced, covering a range of subjects including English, mathematics, science, history, geography, modern languages, physical education, and others. At Key Stage 4, students work towards qualifications such as the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) or vocational qualifications such as Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC). GCSEs are the most common qualifications undertaken by students in NI at the end of Key Stage 4 [34]. They are usually taken in a range of subjects, with students typically taking between 7 and 10 GCSEs. In addition to GCSEs, students may also have the option to take vocational qualifications such as BTECs, which are equivalent to GCSEs but focus on practical, work-related skills.

2. SEN Prevalence in IM Schools in the Republic of Ireland

In this section, a review of the prevalence and categories of SEN in IM primary and post-primary schools in the RoI is provided. The discussion and analysis is focused on schools within Gaeltacht areas and outside of Gaeltacht areas. The review focuses on peer reviewed journal articles and funded reports in this area.

2.1. Gaeltacht and IM Primary Schools in the Republic of Ireland

It is estimated that 9.4% of primary students attending IM primary schools outside the Gaeltacht areas have a SEN diagnosis [35]. The most frequently reported categories of SEN in these schools [35,36] are (1) dyslexia, (2) ASD, (3) EBD, (4) specific speech and language disorder (SSLD). For the 2017–2018 academic year, in IM primary schools, 16.6% of students received additional teaching support from the special education teacher [37].

Research on the prevalence of SEN in Gaeltacht primary schools is limited [36,38,39]. The most recent study [38], in which a survey was completed by 61% (n = 62) of primary Gaeltacht schools, suggests the most frequently reported categories of SEN are (1) dyslexia (6%), (2) ASD (4%), (3) EBD (3%), (4) speech and language disorders (3%). There is a slight variation in these findings when compared to those from the previous study by Barrett et al. [36]. The five most frequently reported categories in that study are (1) specific learning disability (dyslexia), (2) mild general learning disabilities (GLDs), (3) SSLD, (4) ASD, (5) development coordination disorder (DCD). In 2004, 6% (n = 511) of IM primary school students in Gaeltacht areas presented with SEN [39].

When the data gathered for each primary school context is analysed by class, the prevalence of SEN increases as students progress through the school [35,38]. For example, all studies had a very low prevalence rate for junior (age 4–5) and senior infants (age 5–6); these rates grew steadily until fourth class (age 9–10) where they then declined slightly for fifth (age 10–11) and sixth class (age 11–12). This suggests that students with a diagnosis of SEN may not be undertaking the final years of their primary education in IM schools. This may be occurring for a several reasons; for example, many students may transfer because they plan to attend an English-medium post-primary school, and they then move to a feeder English-medium primary school to ensure access to their school of choice. Research has shown that these transfers also may occur due to parental concern around the child’s ability to learn through Irish and on the advice of educational professionals, such as educational psychologists, that this immersion education context is not suitable for a child with SEN [40].

2.2. IM Post-Primary Schools in the Republic of Ireland

There is little research available on the prevalence rates of students with SEN in IM post-primary schools within the Gaeltacht areas [39]. In 2004, 7% of students (n = 324) had a diagnosis of SEN. The five categories of SEN most frequently reported in these schools at the time were (1) specific learning disability (dyslexia) (27%, n = 87), (2) borderline general learning disabilities (GLDs) (26%, n = 27), (3) mild GLDs (20%, n = 65), (4) severe/profound GLDs (9%, n = 31), (5) EBD (including ADHD, 7%, n = 22).

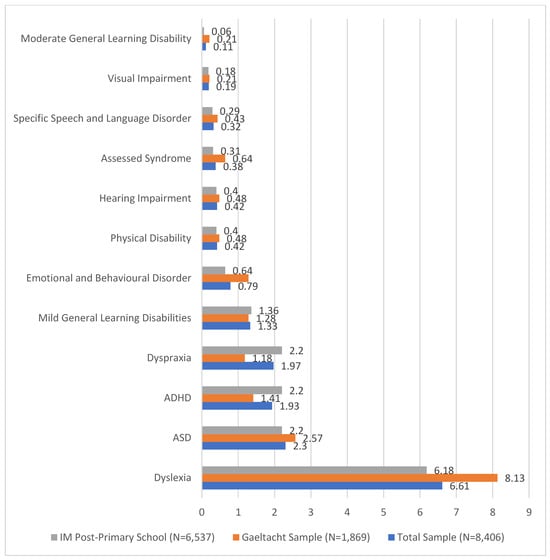

In the most recent study undertaken in the academic school year 2023/2024, it is suggested that there is a prevalence rate of 16.7% (n = 1408) of students diagnosed with SEN in both Gaeltacht and post-primary IM schools [41]. The prevalence rate for Gaeltacht post-primary schools is slightly higher at 18.22% than that of 16.35% for IM post-primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht. No research has been undertaken into why this slight difference occurs. However, Gaeltacht schools may be smaller and this may mean that there is better access to psychological assessments in schools, as each post-primary school in the country has an annual allocation from the National Educational Psychological Service. This prevalence rate for Gaeltacht schools is now over double that of 7% reported by Mac Donnacha et al. [39], suggesting that there has been a considerable increase in the number of students with an official diagnosis of SEN attending Gaeltacht post-primary schools over the last 20 years. The most prevalent categories of SEN for the total sample and for each school type are provided in Figure 1 below. For both school types, dyslexia is the most frequently reported category of SEN, ASD is the second most frequently reported, dyspraxia is the third and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the fourth. Moderate GLD and visual impairments are listed in the bottom two categories for both school contexts. Overall, there is not a notable difference in the reporting of the other categories in both school types.

Figure 1.

The most prevalent categories (%) of SEN by total sample and school type. Data from [41].

3. SEN Prevalence in IM Schools in Northern Ireland

In this section, an overview of will be provided of the prevalence of and categories of SEN reported within IM primary and post-primary schools from 2009 to present in NI. Limited data is available in this area; however, the data available allows for a comparison of how the needs of students in these schools have changed over time and how they compare to the needs of students in English-medium schools.

3.1. IM Primary Schools in Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, there has been limited research undertaken on the prevalence and categories of SEN in IM schools. In 2009, Ní Chinnéide [42], using a quantitative questionnaire, estimated that 17% of primary pupils (N = 2632) in IM schools were identified as having SEN. The most frequently reported categories SEN were (1) moderate GLD (35%), (2) mild GLD (19%), and (3) social and emotional behavioural difficulties (15%). The three most prevalent categories of SEN reported for both IM and English-medium schools at the time were (i) cognitive and learning difficulties, (ii) social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties, (iii) communication and interaction difficulties [42]. However, according to the data, English-medium schools have a greater number of students with medical conditions/syndromes (5%) than IM schools (2%).

Department of Education figures for the 2023/24 [43] school year suggest that 22.5% of students enrolled in the IM sector were identified as having SEN. When this is analysed by context, it is estimated that 21.1% of these students attend IM primary schools, and 30.1% attend IM post-primary schools. These estimates are somewhat higher than that of 18.5% for English-medium primary schools, and 18.2% for English-medium post-primary schools [43,44]. It is suggested that there may be a higher incidence of SEN in IM schools than English-medium schools due to the large number of IM schools that are located in areas of socio-economic disadvantage [44]. However, for those attending IM schools, only 4% of students have a formal statement of SEN, compared to that of 7.6% for students enrolled in English-medium schools [43,44].

The most recent study by Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta [44] further analyses the prevalence and categories of SEN of students in IM schools in NI. From data gathered from 83% (n = 29) of IM primary schools in NI, it was estimated that there is a higher prevalence of SEN of 32% (n = 1194) in these schools than that reported by the Department of Education (21.1%). When the data provided in the report by Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta [44] is further analysed by categories of SEN, it is clear that the most frequently reported category of SEN is cognition and learning [45], with an estimated 12.8% (n = 479) of the school population presenting with difficulties in this area. The second most frequently reported category is social, behavioural, and emotional well-being, with 10.6% (n = 395) presenting with this. The other most frequently reported categories include speech and language difficulties (3.2%, n = 120), communication and social interaction difficulties (2.6%, n = 98), and moderate learning difficulties (0.8%, n = 30).

It can be suggested that the percentage of students identified with SEN in IM schools has increased over the last two decades, indicating either a rising prevalence or improved identification methods. It is evident that there has also been a shift in the most prevalent categories of SEN from 2009 to 2024. Ní Chinnéide [42] found that the most frequently reported categories of SEN were (a) moderate general learning difficulties (GLD) (35%), (b) mild GLD (19%), and (c) social and emotional behavioural difficulties (15%). Meanwhile, the data available for 2024 [43,44] suggests that the most frequently reported categories of SEN are (a) cognition and learning (12.8%), (b) social, behavioural, and emotional difficulties (10.6%), (c) speech and language difficulties (3.2%), (d) communication difficulties (2.6%), (e) moderate learning difficulties (0.8%). It is evident that cognition and learning difficulties remain the most reported category, but social, behavioural, and emotional difficulties have increased in prominence. Moderate general learning difficulties are now a much smaller percentage of reported SEN compared to 2009.

When the data available was analysed and compared to that available for English-medium schools over time, it is evident that in 2009 there was more similarity between the prevalence and categories of SEN in IM and English-medium schools [43,44]. However, slightly fewer students in IM schools had medical conditions (2%) compared to English-medium schools (5%), but equal rates of physical disabilities (2%) were evident in both sectors. For the data available for 2023/2024 [43], it is suggested that there is a slightly higher overall prevalence of SEN in IM schools (22.5%) compared to English-medium schools (18.5% primary, 18.2% post-primary). It is important to be cognisant of the fact that there may be a possible link between higher SEN prevalence in IM schools due to them being located in areas of socio-economic disadvantage. It is also important to be mindful that a lower percentage of students with a formal SEN statement attend an IM school (4%) than an English-medium school (7.6%) [44]. This may be due to difficulties accessing assessments and interventions for the cohort of students attending the IM schools.

3.2. IM Post-Primary Schools in Northern Ireland

In 2009, Ní Chinnéide [42] reported a prevalence rate of 14% for students with SEN in IM post-primary schools. At that time, it was estimated that 47% of the students in these schools who were recorded on the SEN register experienced moderate learning difficulties. Social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties (SEBD) (26%) was listed as the second most prevalent category, and dyslexia and mild learning difficulties third (10%). Other categories reported included dyspraxia (2%), severe learning difficulties (2%), partially sighted (2%), and other (1%).

Data gathered for the 2023/2024 academic year by Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta [44] relates to two standalone IM post-primary schools with an enrolment of 1265 students. In total there are 1856 students being educated at post-primary level in Irish in NI. Therefore, the data gathered by Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta [44] relates to 68% of the IM post-primary school population. No data is available in this context for IM units attached to English-medium schools. These IM units teach through Irish but are under the governance of English-medium schools. Department of Education figures for the academic year 2023/2024 [43] suggest that 30.1% of students in IM post-primary settings have SEN. However, an overall prevalence rate of 49.72% is estimated based on the data provided in the report by Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta [44] with a total of 629 students presenting with a range of SEN. When assessing this figure, it is important to be mindful that the co-morbidity of SEN is not considered, and some students may be counted twice or more based on their varying needs. These prevalence rates for IM post-primary schools suggest that like IM primary schools in NI, there is a higher prevalence of SEN in IM post-primary schools compared to English-medium post-primary schools in the jurisdiction (18.2%) [43,44]. Factors to consider when interpreting the differences in prevalence between IM and English-medium education are (a) the higher number of IM schools located in areas of socio-economic disadvantage compared to English-medium schools, (b) the availability of appropriate assessment and timely identification, access to early intervention, and (c) access to appropriate support in the Irish language.

Yet again for the post-primary schools, cognition and learning is the most frequently reported category with an estimated 24.8% (n = 314) of the sample presenting with these difficulties. Social, emotional, behavioural, and well-being difficulties is listed second (14%, n = 187) and dyslexia, which is a specific learning difficulty, is listed third (4.3%, n = 51). The other most prevalent categories are speech and language difficulties (1.5%, n = 20) and communication and social difficulties (1.5%, n = 19).

When an analysis and comparison of SEN in IM post-primary schools (2009 vs. 2023/2024) was undertaken, it was clear that there has been an increase in the overall SEN prevalence rate over time. For example, in 2009, 14% of IM post-primary students were reported with SEN [42], compared to Department of Education figures for 2023/2024 of 30.1% [43]; however, Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta [44] report higher figures again of 49.72% for the 2023/2024 academic year (though this figure may be inflated due to co-morbidity). This suggests that SEN prevalence in IM post-primary schools has more than doubled since 2009 based on Department of Education [43] data and more than tripled based on Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta’s findings [44]. There has also been a shift in the needs of students over this time. In 2009 [42], moderate general learning difficulties (47%) was the most frequently reported category of SEN, SEBD (26%) second, and then dyslexia and mild general learning difficulties (10%). For the academic year 2023/2024 [44], it is suggested that cognition and learning (24.8%) is the most prevalent category. SEBD is listed second but at a lower prevalence of 14% than that of 26% in 2009. Dyslexia is also reported at the lower figure of 4.3% for the academic year 2023/2024 compared to that of 10% in the 2009 report [42,44]. The data [42,43,44] also suggests that the gap between SEN prevalence in IM and English-medium post-primary schools has widened, with IM schools facing more challenges, such as a higher number of IM schools located in socio-economically disadvantaged areas and the lack of Irish-language resources, assessments, and early intervention services.

4. Conclusions

The analysis and description provided are significant as they suggest that the needs of students in IM schools across the island of Ireland has changed over the last 20 years. In relation to overall SEN prevalence trends, it is suggested that SEN prevalence is significantly higher in IM post-primary schools compared to IM primary schools. This may suggest that the identification of SEN increases as students’ progress through their education. For example, there is a prevalence rate of 9.4% for students in IM primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht and a prevalence rate of 16.35% for students in IM post-primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht. A similar pattern is evident for IM primary and post-primary schools in Gaeltacht areas and Northern Ireland. The prevalence rate for Gaeltacht post-primary schools (18.22%) suggests that the number of students who present with SEN in this school type is more than double that of 7% reported in 2004 [38,39]. SEN prevalence increases as students move to post-primary education, which may be due to improved diagnostic tools and evolving educational policies. This may be influenced by the fact that there are no assessments available to educational psychologists in the Irish language and more parents waiting to see if their child catches up when learning through Irish before formally assessing them. Furthermore, the lack of assessments available through Irish may negatively impact on the identification of students with SEN due to them being only assessed through one of their languages, English [46,47]. This could lead to a disproportionate number of students being identified with SEN as their total abilities are not being assessed in both of their languages [48,49]. Therefore, future research should consider the development of standardised assessments through Irish to ensure comparability. Also, it is imperative that the government fund the development of Irish language assessments for educational psychologists and speech and language therapists so that all students in IM education have equal opportunities.

Another challenge that may contribute to the increase in SEN identification in post-primary schools is that lack of appropriate support structures in primary education for the identification and support of students with SEN, there is currently a lack of resources available to schools in relation to accessing services by the educational psychologist, speech and language, and occupational therapist [47,50]. Also publicly, there are long waiting lists for the assessment of needs process [51]. Potentially there may also be gaps in teacher education in relation to the identification of SEN at the initial teacher education level and this would benefit from being further examined [52]. Specialised professional development for IM educators in the area of special education in minority language contexts is also an area that would benefit from further development [52,53,54,55]. It would be beneficial if all IM educators received in-school professional development in this area that was government funded. This would enable teachers to work in bilingual educational settings, to differentiate between the nuances of second language learning, bilingualism and SEN. It has been stated that many IM schools find it difficult to implement a whole school approach to inclusion due to a lack of staff and resources. Therefore, the rise in diagnoses at the post-primary level should also prompt a closer examination of inclusivity within schools. If teaching methods and school environments are not sufficiently inclusive or adaptive, students with diverse needs may struggle unnecessarily, leading to increased referrals and diagnoses as a way to access support. In this sense, a less inclusive didactic approach can indeed act as a trigger for diagnosis, not necessarily because more students are developing difficulties, but because the system is not meeting their needs in the first place. Assessing inclusivity alongside diagnostic trends could offer valuable insight into whether the educational framework is proactively supporting all learners or inadvertently pathologizing differences.

The higher SEN prevalence in IM schools in NI, in socio-economically disadvantaged areas, suggests systemic challenges in relation to resource allocation [47]. A critical discussion on funding disparities, access to learning supports, and availability of Irish-language assessments and resources is needed to ensure equity of access for students in IM schools when compared to their peers in English-medium schools [56]. Further investigation and discussion is needed to unpack the complex interplay between socio-economic status, language acquisition challenges, and SEN identification. This is important as international research in bilingual and immersion education suggests that socio-economic disadvantages can compound learning difficulties, particularly for students with SEN who may struggle with language proficiency in both their home language and the immersion language. This aspect could be further explored in the future to provide a more nuanced understanding of the intersection between language policy, social inequality, and SEN support structures. Longitudinal studies on SEN progression in immersion education or qualitative research on student experiences, would strengthen the understanding of SEN in these contexts going forward.

The findings of this entry are important as they add to the limited international knowledge available regarding SEN prevalence and categories in primary and post-primary immersion education internationally. Therefore, it is hoped that the results of the study may be of significance and have implications for other forms of bilingual and immersion education internationally.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was collected for this entry.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bialystok, E. Aging and bilingualism: Why does it matter? Linguist. Approaches Biling. 2016, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Bilingual and Immersion Programs. In The Handbook of Language Teaching; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, W.E.; Baker, C. Key concepts in bilingual education. Biling. Multiling. Educ. 2017, 3, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Duibhir, P.Ó. Immersion Education: Lessons from a Minority Language Context; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 111. [Google Scholar]

- McAdory, S.E.; Janmaat, J.G. Trends in Irish-medium education in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland since 1920: Shifting agents and explanations. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2015, 36, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta. Celebrating Irish Medium Education 2021. 2021. Available online: https://niopa.qub.ac.uk/bitstream/NIOPA/14890/1/ION-2021-master.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Údarás na Gaeltachta. The Gaeltacht. Available online: https://udaras.ie/an-ghaeilge-an-ghaeltacht/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Central Statistics Office. Census of Population 2022 Profile 8–The Irish Language and Education. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpp8/censusofpopulation2022profile8-theirishlanguageandeducation/irishlanguageandthegaeltacht/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Ceallaigh, T.J.Ó.; Dhonnabhain, Á.N. Reawakening the Irish language through the ırish education system: Challenges and priorities. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2015, 8, 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gaeloideachas. Statistics. Available online: https://gaeloideachas.ie/i-am-a-researcher/statistics/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Government of Ireland. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act 2024. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2004/act/30/enacted/en/html (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- National Council for Special Education. Supporting Students with Special Educational Needs in Schools. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Supporting_14_05_13_web.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Northern Ireland Direct. Support for special educational needs. Available online: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/support-special-educational-needs (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Banks, J. A Winning Formula? Funding Inclusive Education in Ireland. In Resourcing Inclusive Education; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; Volume 15, pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.; Thompson, S.; Doyle, D.M.; Ferri, D. Inclusive education and the law in Ireland. Int. J. Law Context 2023, 19, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R.; Shevlin, M.; Winter, E.; O’Raw, P. Special and inclusive education in the Republic of Ireland: Reviewing the literature from 2000 to 2009. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2010, 25, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. New SEN Framework. Available online: https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/new-sen-framework (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). Special Classes. Available online: https://ncse.ie/special-classes-2 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Department of Education. Special Educational Needs. Available online: https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/topics/special-educational-needs (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- National Council for Special Education. Education Provision for Students with Special Educational Needs. Available online: https://ncse.ie/education-provision-for-students-with-special-educational-needs (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Department of Education. Educational provision for pupils with Specific Speech and Language Disorder: Special Classes attached to Mainstream Primary Schools in Ireland. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/133317/15aec2bb-671e-4ffe-b3c5-2a9daed448d5.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Department of Education. Educational Provision for Children and Young People with a Specific Learning Disability. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/259594/0a8c612b-46fd-451f-bdab-462ef86c0dc7.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Department of Education. Exemptions from the Study of Irish Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/132103/f10eb5b6-fb2c-4dc9-bcc8-6d7c33e8b973.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- National Council for Special Education. Special Schools. Available online: https://ncse.ie/special-schools (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Coolahan, J.; Drudy, S.; Hogan, P.; McGuiness, S. Towards a Better Future: A Review of the Irish School System; Irish Primary Principals Network and the National Association of Principals: Cork, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Science. A Brief Description of the Irish Education System. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/24755/dd437da6d2084a49b0ddb316523aa5d2.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). Primary Curriculum Framework for Primary and Special Schools. Available online: https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/84747851-0581-431b-b4d7-dc6ee850883e/2023-Primary-Framework-ENG-screen.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). A Curriculum Framework for Guidance in Post-Primary Education: Discussion Paper. Available online: https://ncca.ie/en/resources/curriculum-framework-guidance-post-primary/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). Transition Year. Available online: https://www.curriculumonline.ie/senior-cycle/transition-year/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Northern Ireland Direct. Types of School. Available online: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/types-school (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- CCEA. The Northern Ireland Curriculum Primary. Available online: https://ccea.org.uk/learning-resources/northern-ireland-curriculum-primary (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Cross Border Partnerships. The Education System in Northern Ireland. Available online: https://www.cbpes.com/the-education-system-in-northern-ireland (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- CCEA. Post-Primary Quick Guide to the Curriculum. Available online: https://ccea.org.uk/learning-resources/parents-guides-northern-ireland-curriculum (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Northern Ireland Direct. GCSEs. Available online: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/gcses (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Travers, J. The prevalence and types of special educational needs in Irish immersion primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, B.; William, K.; Prendeville, P. Special educational needs in bilingual primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2020, 39, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Travers, J. A survey of assessment and additional teaching support in Irish immersion education. Languages 2021, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Comhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta. Meeting Special Educational Needs in Gaeltacht Primary Schools. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/Freastal-ar-Riachtanais-Speisialta-Oideachais-i-mBunscoileanna-Gaeltachta-Tuarasc%C3%A1il-Taighde-2024.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Mac Donnacha, S.; Ní Chualáin, F.; Ní Shéaghdha, A.; Ní Mhainín, T. Staid Reatha na Scoileanna Gaeltachta. An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta (COGG). 2005. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/Staid-Reatha-na-Scoileanna-Gaeltachta-2004.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Nic Aindriú, S. The reasons why parents choose to transfer students with special educational needs from Irish immersion education. Lang. Educ. 2022, 36, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, S. Special Educational Needs in Post-Primary Gaeltacht and Irish-Medium Schools. An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta (COGG). Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland. 2005, to be submitted.

- Deirdre Ní Chinnéide. The Special Educational Needs of Bilingual (Irish-English) Children, 52. POBAL, Education and Training. 2009. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/11010/7/de1_09_83755__special_needs_of_bilingual_children_research_report_final_version_Redacted.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Department of Education. Statistics. Available online: https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/topics/statistics-finance (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta. The Provision for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities in Irish-Medium Education. 2024. Available online: https://www.comhairle.org/english/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/11/The-Provision-for-Special-Educational-Needs-and-Disabilities-in-Irish-medium-Education-November-2024.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Education Authority. What Are the Specific SEN Categories in the SEN Register? Available online: https://send.eani.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-09/SEN%20%26%20Medical%20Categories%20leaflet%20for%20parents%20and%20young%20people.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Murtagh, L.; Seoighe, A. Educational psychological provision in Irish-medium primary schools in indigenous Irish language speaking communities (Gaeltacht): Views of teachers and educational psychologists. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 1278–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, E. Inclusive and Special Education in English-Medium, Irish-Medium, and Gaeltacht Schools: Policy and Ideology of a Fragmented System. In Inclusive Education in Bilingual and Plurilingual Programs; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hulse, D.; Curran, E. Disabling language: The overrepresentation of emergent bilingual students in special education in New York and Arizona. Fordham Urb. LJ 2020, 48, 381. [Google Scholar]

- Cuba, M.J.; Tefera, A.A. Contextualizing multilingual learner disproportionality in special education: A mixed-methods approach. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2024, 126, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó. The Challenges Facing Irish-Medium Primary and Post-Primary Schools When Implementing a Whole-School Approach to Meeting the Additional Education Needs of Their Students. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houses of the Oireachtas. Disability and Special Needs Provision: Motion [Private Members]. Available online: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/2024-09-19/36/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Connaughton-Crean, L.; Travers, J. The CPD needs of Irish-medium primary and post-primary teachers in special education. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Connaughton-Crean, L.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Travers, J. The Design and Content of an Online Continuous Professional Development Course in Special Education for Teachers in Irish Immersion Primary and Post-Primary Schools. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.; Dunlap, K.; Brister, H.; Davidson, M.; Starrett, T.M. Sink or swim? Throw us a life jacket! Novice alternatively certified bilingual and special education teachers deserve options. Educ. Urban Soc. 2013, 45, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D. A Conceptual Framework of Bilingual Special Education Teacher Programs. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, Tempe, AZ, USA, 30 April–3 May 2003; pp. 1960–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Nic Aindriú, S. Equality of access to minority language assessments and interventions in immersion education: A case study of Irish-medium education. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. 2024, 13, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).