A Guide to a Mixed-Methods Approach to Healthcare Research

Definition

1. Background

2. Historical Background and Development

3. Design of Mixed-Methods Research

3.1. Types of Mixed-Methods Designs

3.2. Formulating Research Questions for Mixed-Methods Studies

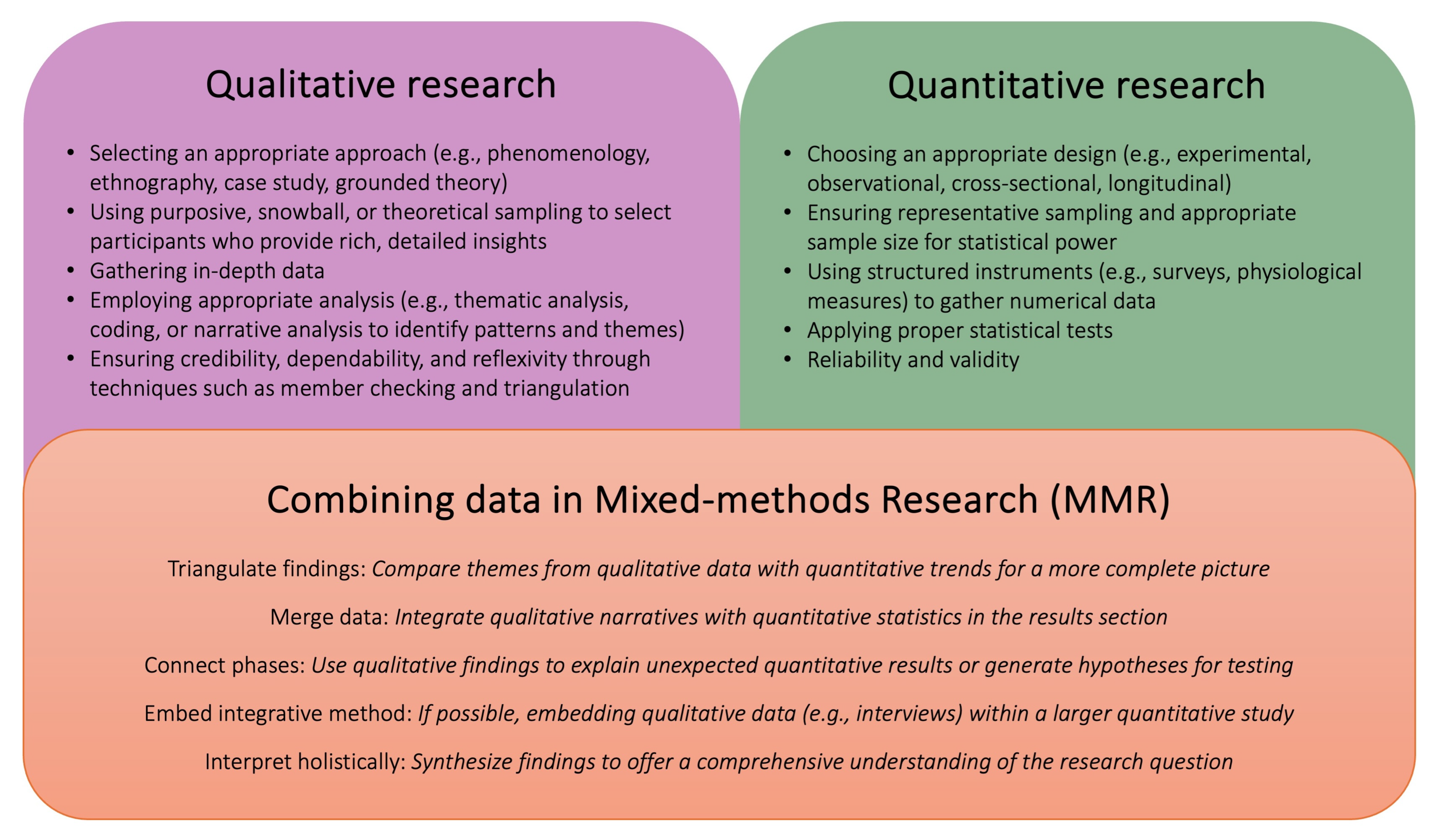

4. Data Collection Technique

5. Data Analysis Techniques

Meta-Inference in Mixed-Methods Research

6. Applications in Healthcare

7. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K.M.T.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Jiao, Q.G. A Mixed Methods Investigation of Mixed Methods Sampling Designs in Social and Health Science Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B. Elaboration, Generalization, Triangulation, and Interpretation: On Enhancing the Value of Mixed Method Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 20, 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Poudel, P.; Chimoriya, R. Qualitative Methodology in Translational Health Research: Current Practices and Future Directions. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, L.A.; Nembhard, I.M.; Bradley, E.H. Qualitative and Mixed Methods Provide Unique Contributions to Outcomes Research. Circulation 2009, 119, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Page, A.; Kent, J.L.; Arora, A. Pathways Linking Housing Inequalities and Health Outcomes among Migrant and Refugee Populations in High-Income Countries: A Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research Through Joint Displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Kent, J.L.; Page, A. Housing inequalities and health outcomes among migrant and refugee populations in high-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Valencia, M.M. Principles, Scope, and Limitations of the Methodological Triangulation. Investig. Y Educ. Enfermería 2022, 40, e03. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Caracelli, V.J.; Graham, W.F. Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1989, 11, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Maharaj, R.; Naidu, S.; Chimoriya, R.; Bhole, S.; Nash, S.; Jones, C. Views of Indian Migrants on Adaptation of Child Oral Health Leaflets: A Qualitative Study. Children 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesely, P.M. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Approaches to Qualitative-Quantitative Methodological Triangulation. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wasti, S.P.; Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E.R.; Sathian, B.; Banerjee, I. The Growing Importance of Mixed-Methods Research in Health. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2022, 12, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Slate, J.R.; Leech, N.L.; Collins, K.M. Mixed data analysis: Advanced integration techniques. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2009, 3, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.S.; Muntean, E.-A.; Mallen, C.D.; Borovac, J.A. Data Collection Theory in Healthcare Research: The Minimum Dataset in Quantitative Studies. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoa, B.T.; Hung, B.P.; Hejsalem-Brahmi, M. Qualitative research in social sciences: Data collection, data analysis and report writing. Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag. 2023, 12, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawar Lina, N.; Dunbar Ghada, B.; Aquino-Maneja Emma, M.; Flores Sarah, L.; Squier Victoria, R.; Failla Kim, R. Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, and Triangulation Research Simplified. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2024, 55, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, V.V.; Page, S.D. Using mixed methods in cardiovascular nursing research: Answering the why, the how, and the what’s next. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 20, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australas. Mark. J. 2024, 14413582241264619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cruz, N.; Ong, N. Data Visualisation of Quantitative Findings: Infusing Statistics with Emotion, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, J.H.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Application of mixed methods for international and cross-cultural research. In Handbook of School Psychology in the Global Context: Transnational Approaches to Support Children, Families and School Communities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Younas, A.; Fàbregues, S.; Creswell, J.W. Generating metainferences in mixed methods research: A worked example in convergent mixed methods designs. Methodol. Innov. 2023, 16, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, A.; Fàbregues, S.; Munce, S.; Creswell, J.W. Framework for types of metainferences in mixed methods research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2025, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010, 341, c4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorten, A.; Smith, J. Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKim, C.A. The Value of Mixed Methods Research: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2015, 11, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlund, U.; Kidd, L.; Wengström, Y.; Rowa-Dewar, N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Aarons, G.A.; Horwitz, S.; Chamberlain, P.; Hurlburt, M.; Landsverk, J. Mixed Method Designs in Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Rana, K.; Manohar, N.; Li, L.; Bhole, S.; Chimoriya, R. Perceptions and Practices of Oral Health Care Professionals in Preventing and Managing Childhood Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimoriya, R.; MacMillan, F.; Lean, M.; Simmons, D.; Piya, M.K. A qualitative study of the perceptions and experiences of participants and healthcare professionals in the DiRECT-Australia type 2 diabetes remission service. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halcomb, E.; Hickman, L. Mixed methods research. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abowitz, D.A.; Toole, T.M. Mixed Method Research: Fundamental Issues of Design, Validity, and Reliability in Construction Research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Aitken, S.J.; Chimoriya, R. Interdisciplinary Approaches in Doctoral and Higher Research Education: An Integrative Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, J.P. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Rev. Saude Publica 2022, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadnick, N.A.; Poth, C.N.; Guetterman, T.C.; Gallo, J.J. Advancing discussion of ethics in mixed methods health services research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Design | Convergent Parallel Design | Explanatory Sequential Design | Exploratory Sequential Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Details | Qualitative and quantitative data are collected simultaneously and analyzed independently before merging results. | Quantitative data are collected and analyzed first, followed by qualitative data to explain the findings. | Qualitative data are collected first to explore a phenomenon, followed by quantitative data to generalize findings. |

| Research Question | It seeks to understand a phenomenon from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives simultaneously. | It aims to explain or elaborate on quantitative results using qualitative insights. | It qualitatively explores a phenomenon in-depth before quantifying the findings. |

| Methods | Data collection occurs in parallel using surveys, experiments, interviews, or focus groups. Both datasets are analyzed independently using statistical and thematic analysis, and results are merged or compared to identify similarities, differences, or complementarities. | The first phase involves collecting and analyzing quantitative data (e.g., surveys, secondary data analysis, and experiments) to identify patterns or relationships. The second phase consists of qualitative data collection (e.g., interviews and focus groups) to provide deeper explanations for the quantitative results. | The first phase involves qualitative data collection (e.g., in-depth interviews, ethnography, and focus groups) to explore key themes or generate hypotheses. The second phase uses quantitative methods (e.g., surveys, structured observations, and experimental designs) to test or generalize findings to a larger population. |

| Context | This is suitable when both types of data provide complementary insights into a research problem. | This is useful when quantitative data need further explanation through qualitative insights. | This is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon and qualitative insights are needed before generalization. |

| Resources | These require expertise in both qualitative and quantitative analysis; data collection must be well coordinated. | These require time for sequential data collection and expertise in both methodologies. | These demand qualitative expertise first, followed by quantitative skills for validation. |

| Key Strengths | These provide a comprehensive understanding; they allow for a direct comparison of different data types. | These offer deeper insights into quantitative findings; helps clarify unexpected results. | These capture rich qualitative insights before quantification; they are useful for theory development. |

| Key Limitations | These require substantial coordination; there is potential difficulty in integrating data. | These are time-consuming due to sequential phases; a qualitative follow-up may not fully explain the results. | Initial qualitative findings may not be easily generalizable; these require expertise in both methods. |

| Data Collection Techniques | Description | Examples of Data Collection Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Data Collection | This involves methods that yield numerical data suitable for statistical analysis. These techniques are designed to measure variables and quantify relationships between them. They provide objective, reliable, and generalizable data that can be used to test hypotheses and identify patterns [7,25]. |

|

| Qualitative Data Collection | This technique focuses on gathering non-numerical, rich, and contextual data that capture individuals’ thoughts, experiences, and behaviors. This approach helps uncover meanings, themes, and personal insights that cannot be measured quantitatively [6,26]. |

|

| Integration of Data Collection | A defining feature of mixed-methods research involves collecting both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a holistic view of the research problem. Integration can occur simultaneously (data collected at the same time) or sequentially (one method follows another) [12,27]. |

|

| 20-Step Mixed-Methods Integration & Rigorous Analytical Guidelines (20-MIRAGE) |

|---|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rana, K.; Chimoriya, R. A Guide to a Mixed-Methods Approach to Healthcare Research. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5020051

Rana K, Chimoriya R. A Guide to a Mixed-Methods Approach to Healthcare Research. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(2):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5020051

Chicago/Turabian StyleRana, Kritika, and Ritesh Chimoriya. 2025. "A Guide to a Mixed-Methods Approach to Healthcare Research" Encyclopedia 5, no. 2: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5020051

APA StyleRana, K., & Chimoriya, R. (2025). A Guide to a Mixed-Methods Approach to Healthcare Research. Encyclopedia, 5(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5020051