Definition

Work-related stress is a critical issue that demands prevention strategy and continuous monitoring due to its widespread influence on workers, businesses, and the global economy. The primary drivers of employees’ work-related stress are psychosocial risks, which arise when key work characteristics—such as job demands, autonomy, or role clarity—are mismanaged, leading to harmful consequences. Conversely, effectively managing these factors can promotes well-being and performance. Supervisors play a central role in this dynamic process of either mitigating or exacerbating psychosocial working conditions. As such, stress-preventive management competencies (SPMCs) are essential for promoting employee and organisational health. SPMCs refer to a set of supervisory behaviours—including planning, organising, setting objectives, and creating and monitoring systems—that contribute to a positive perception of the psychosocial work environment among employees. This entry, by approaching the existing literature on work stress models, psychosocial perspectives, and related management competencies frameworks, aims to provide a comprehensive overview of SPMCs, identifying key insights and proposing directions for future research.

1. Introduction

The term “stress” has its etymological roots in the Latin strictus, meaning “narrow”, later evolved into Old French estrece and Anglo-Norman estresce, signifying “tightness” or “oppression” [1,2]. However, the scientific interest in the stress conceptualization was stimulated by Selye in 1936. Selye initially defined stress as a non-specific physiological body response to any demand for change [3] and later refined this definition as “the state manifested by a specific syndrome, consisting of all the non-specifically induced changes within a biological system” ([4], p. 64). In his animal studies, Selye found that various harmful environmental stimuli—such as high temperatures, physical injuries, or toxic substances—triggered both specific effects and non-specific somatic symptoms, such as ulcers in the stomach or intestines, regardless of the nature of the stressor.

Building on Selye’s foundational work on physiological stress responses, occupational health research has shifted focus towards understanding how organisational and psychosocial factors influence stress experiences in the workplace. Specifically in occupational health science, three mains but overlapping approaches have been developed to conceptualise work-related stress: the engineering, the physiological, and the psychological [5]. The engineering approach considers stress a noxious characteristic of the work environment. The physiological approach defines stress as the effect of a broad-spectrum of adverse stimuli targeting two neuroendocrine systems: the sympathetic adrenal medullary system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis ([6]; see [7] for a review). Meanwhile, the psychological approach, integrating cognitive and emotional processes, conceptualises stress as a dynamic interaction between individuals and their work environment.

This latter approach received even more interest because it replies to a shared limit of the engineering and physiological approaches, which build on a “relatively simple stimulus-response paradigm and largely ignore individual differences of a psychological nature” ([5], p. 35). In contrast, the psychological approach highlights how different individuals may appraise the same environmental stimulus differently, leading to different psychophysiological responses. Similarly, a single individual may interpret the same stimulus differently depending on the situation. Influential contributions within this domain include Lazarus [8], who introduced the notions of cognitive appraisal (i.e., meaning attributions to stimuli) and coping (i.e., individual and trainable strategy to tackle stress), or the Person-Environment Fit theory [9], which focused the (in) congruence degree between the employee’s attitudes/abilities and the job demands as an antecedent of work-related stress.

Nowadays, a shared definition of work-related stress is “the harmful physical and emotional response caused by an imbalance between the perceived demands and the perceived resources and abilities of individuals to cope with those demands” ([10], p. 2; see [11] for a review). The primary causes of work-related stress are commonly referred to as psychosocial risks [5,10]. These risks emerge when critical work characteristics (i.e., psychosocial factors, such as demands, control, support, or role, which define work organisation, work design and labour relations) are mismanaged. Together, work-related stress and psychosocial risks are remarkable public health and safety threats, significantly impacting workers, businesses, and the economy (e.g., [12,13,14,15]).

To mitigate these risks, various countries have introduced legislative measures to establish a culture of risk prevention in the workplace. In Europe, employers are legally obligated to reduce workers’ exposure to psychosocial risks following the 1989 European Commission Council Framework Directive (89/391/EEC). Similar regulations exist in some Latin American countries, such as Colombia, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic, and in parts of Africa, including Angola, Congo, and Egypt. However, other nations, including the United States, Russia, and Australia, lack comprehensive legal frameworks addressing psychosocial risks. These discrepancies contribute to significant inequalities in worker protection and occupational health outcomes [16].

Given the complexity of the phenomenon, best practices suggest that programmes aimed at reducing work stress and improving well-being require multi-stakeholder involvement (e.g., [17,18]), multilevel interventions (e.g., [19]), structured and participatory approaches (e.g., [20]), strategic and dynamic perspectives (e.g., [21]), and intervening before the symptoms arise by designing preventive interventions (e.g., [14,22,23]).

Notably, the main, but not only, social actor who affects the psychosocial work environment of employees is the supervisor [24,25,26]. By communicating, organising, and designing work, the supervisors’ agency is remarkably involved in optimising or mismanaging psychosocial factors. Additionally, they can be emotionally contagious within their team (e.g., [27,28]) and they play a crucial role in the intervention process, organisational development, and change [29,30,31]. For these reasons, interventions aimed at developing leadership and manager behaviours are considered effective [32,33] and recommended [14,34].

Leadership development is a relatively new field of study that is longitudinal and multilevel in nature [35], which is growing in both research [36] and practice [37]. However, the literature on supervisors-focused interventions to prevent work-related stress and psychosocial risks is not yet in the maturity stage. Organisational interventions on supervisors highlight a general employing of performance-oriented frameworks, such as transformational or transactional leadership styles (e.g., [38,39,40,41]). These traditional approaches may not fully grasp specific behaviours related to employee well-being [31,42].

Conversely, only four alternative approaches have explicitly framed the promotion of employee health and the prevention of psychosocial risks as core leadership responsibilities.

Gilbreath and Benson developed the first approach in the early 2000s [43]. Shortly thereafter, the Management Competencies for Preventing and Reducing Stress at Work (MCPARS) framework was developed and preliminary tested [25,26,44]. While in 2018, St-Hilaire et al. [45] suggested a new competency-based approach, and in 2025 a study defined and identified the digital stress-preventive management competencies [46]. These latter frameworks are broad, behaviour-based, and aim to identify specific management competencies that can optimise psychosocial factors perceived by subordinates. The theoretical perspective underpinning this area of research is that “stress management is a part of normal general management activities” for leaders ([25], p. 11) and that “good supervision is more than a nice to have” ([24], p. 112).

A comprehensive review regarding this approach is lacking in the literature. This contribution might open new research questions and clarify the state of the art on a remarkably interesting subject for practices such as organisational interventions and theory on psychosocial risk prevention. Accordingly, this entry reviews current knowledge on stress-preventive management competencies and outlines possible directions for future research in this field.

In order to provide supporting background on the topics of our entry, the ensuing paper section briefly outlines (2) the psychosocial perspective on work-related stress. Then, we describe the (3) stress-preventive management competencies framework and (4) the conclusion and prospects in this field.

3. Stress-Preventive Management Competencies

The association between supervisory behaviour and employee well-being has been empirical research topic since the late 1970s. One of the earliest studies in this field, conducted by Gavin and Kelley [73], identified strong correlations between employees’ self-reported well-being and their perceptions of supervisory support and consideration. Over the years, a growing body of research has confirmed that effective supervision is critical in shaping employees’ health and well-being [27].

In recent decades, models of “healthy leadership” have gained increasing attention within the scientific community. This literature was primarily inspired by Hanson’s work [74], which in 2004 proposed a conceptualisation of health-promoting leadership based on three core dimensions: personal leadership, referring to a leader’s competence to provide support, recognition, and constructive feedback; pedagogical leadership, which emphasises the balance between employee well-being and organisational goals; and strategic health-promoting leadership, which involves designing and implementing policies that foster a healthy workplace environment. These models focus on leadership as a social influence process [75], examining supervisors’ specific attitudes, values, and behaviours that can contribute to employees’ health outcomes [33].

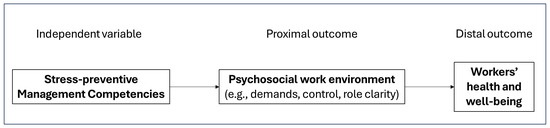

Although there is a strong evidence base supporting the central role of managers in health and well-being initiatives, efforts to train and develop them in this domain have yielded limited success. A recent meta-analysis examining the effects of manager training on stress, well-being, and absenteeism concluded that, although such interventions are widely implemented, few consistent positive effects have been demonstrated [76]. This suggests a need for alternative approaches to equip managers with the necessary tools to create a healthier workplace. One promising direction is the development of stress-preventive management competencies [31]. Unlike “healthy leadership” models, which focus on leaders’ personal attributes, values, and general leadership style, the stress-preventive management competencies framework examines specific managerial daily role-related supervisors’ behaviours that influence employees’ health and well-being (i.e., distal outcomes) by shaping the psychosocial work environment (i.e., proximal outcome). These frameworks recognise that supervisors impact stress not only through direct interactions with employees, but also through their organisational and managerial decisions regarding workload distribution, objective communication clarity, workers’ job autonomy or supportive behaviours. See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of the conceptual model of this field of study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the field of study.

According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology [77], competence is: “the ability to exert control over one’s life, to cope with specific problems effectively, and to make changes to one’s behaviour and one’s environment, as opposed to the mere ability to adjust or adapt to circumstances as they are”. Applied to the workplace context, competency frameworks refer to a complete collection of skills and behaviours required for an individual to perform their role effectively [78]. Thus, focusing on the supervisor’s management skills and behaviours required, the manager is a person who takes on a management role, which comprises activities such as planning, organising, setting objectives, and creating and monitoring systems and ensuring standards are met [25]. Meanwhile, the stress-preventive management competencies are the consolidated supervisors’ competencies of planning, organising, setting objectives, and creating and monitoring systems that can optimise a positive psychosocial work environment’s perception of workers.

To date, only four approaches explicitly considered stress-preventive management behaviours:

- The first approach, developed by Gilbreath and Benson [43], pioneered this field. Using a mixed-method approach, combining interviews with supervisors and employees with psychometric data analysis, the authors identified 63 supervisory behaviours influencing employees’ psychosocial working conditions. As a result, the authors developed and validated a Tool employing a Likert-type scale [76] (i.e., Supervisor Practices Instrument-SPI). The management behaviours identified by the authors included those related to job control (e.g., “Is flexible about how I accomplish my objectives”); leadership (e.g., “Makes me feel like part of something useful, significant, and valuable”); communication (e.g., “Encourages employees to ask questions”); consideration (e.g., “Shows appreciation for a job well done”); social support (e.g., “Steps in when employees need help or support”); group maintenance (e.g., “Fails to properly monitor and manage group dynamics”); organising (e.g., “Plans work to level out the load, reduce peaks and bottlenecks”); and looking out for employee well-being (e.g., “Strikes the proper balance between productivity and employee well-being”). The framework was supported by empirical evidence linking these behaviours to employee well-being, job stress, presenteeism, and job neglect [43,79,80]. However, despite its theoretical significance, this model has yet to be applied in intervention studies.

- The management competencies for preventing and reducing stress at work (MCPARS) framework was developed by Yarker et al. [25,26,44] by explicitly employing as a reference the Management Standards (MS) approach to identify stress-preventive management behaviours [68,69]. The authors, following several qualitative (i.e., interviews and focus groups with work stress experts, managers and employees) and quantitative research steps, identified 66 behaviours clustered in four key management competencies (composed of three sub-competencies each) as essential to managing the six psychosocial factors of MS (i.e., demands; control, role, support, relationship and change): (1) Respectful and Responsible, which comprises the supervisors’ behaviours of integrity (i.e., be respectful and honest to employees), is emotion management (i.e., behaves consistently and calmly), and consideration (i.e., thoughtful in managing others and delegating); (2) Managing and Communicating existing and future Work includes the sub-competencies of proactive work management (i.e., monitors existing work, allowing future prioritisation and planning), problem-solving (i.e., deals with problems promptly), and participative (listens and consults with team, provides autonomy and opportunities); (3) Reasoning/Managing Difficult Situations which includes the sub-competencies of conflict management (i.e., deals with conflicts fairly and promptly), use of organisational resources (e.g., seeking advice when necessary from managers, human resources, or occupational health services) and taking responsibility for resolving issues (e.g., adopting a supportive and accountable approach to problem-solving); finally, (4) Managing the Individual within the Team includes the subdimensions of personal accessibility (i.e., being available for personal conversations), sociability (i.e., engaging socially and using humour), and empathetic engagement (i.e., striving to understand employees’ motivation, perspectives, and personal circumstances).This framework is arguably the most advanced, involving a validated 66-item questionnaire (employing a Likert-type scale [81]) for the measurement of management competencies ([26]; see [82] for a 36-item short-version) and a practical intervention strategy noted by EU-OSHA and Eurofound [34] as an example of excellent practice in promoting positive supervisory behaviours. These latter proposed two intervention protocols that translate the MCPARS framework into practical leadership development through three core aims: (1) increasing awareness regarding the importance of positive behaviours among supervisors, (2) enhancing self-awareness by identifying area of growth, and (3) equipping supervisors to enhance and further develop their skills, creating a personal action plan for development. The primary intervention protocol adopts upward feedback (i.e., team ratings exposure) as a key developmental mechanism to achieve aim 2; meanwhile, the secondary protocol proposes a self-reflection approach where leaders self-assess their competency level and reflect on the development needs with a standard cut-off (see [83]).Several research supports the of MCPARS’s competency model. From an employee’s point of view, the four management competencies were empirically found to be related to the psychosocial factors of the Management Standards approach, with odds of psychological distress, resilience, work engagement and workplace bullying perceptions [83,84,85]. Meanwhile, supervisors’ self-assessed MCPARS have been linked to team members’ affective well-being through the mediating effect of the psychosocial work environment [72]. More recently, two investigations that compared the managers’ and employees’ views of the competencies (i.e., self-other agreement) highlighted the importance of promoting manager-team alignment on high competencies to effectively prevent psychosocial risks and optimise well-being, mental health, and job performance [71,86]. Conversely, the practical application of this framework received few evidence about the proposed intervention protocols. The original evaluation [44] reported high levels of managerial engagement during the training activities, along with self-reported improvements in competencies following the intervention. Consistently, team members also reported an increase in their supervisors’ management competencies after the training—particularly in the case of initially less effective managers who had received upward feedback.More recently, two studies adopting the self-reflection approach have explored both the outcomes and processes of such interventions. In Japan, Adachi et al. [87] found that managers perceived themselves as more competent one-month post-training, while no effect was found on teams’ work-engagement. While Toderi et al. [88] in Italy, found the hierarchical and positive relationship in achieving the training aims. Specifically, the achievement of the increased awareness of the importance of positive managers’ behaviours for well-being (aim 1) had a positive effect on the increase in self-awareness (aim 2) which, in turn, elicited a positive impact on the development of a satisfactory action plan (aim 3). In this mechanism, two process variables, such as the activities understanding and the positive perceptions regarding the overall project, better examined the hierarchical achievements of the training aims.Notably, no intervention studies involving upward feedback are currently available in the literature. This is particularly relevant given that feedback is a critical mechanism of leadership development, as it enhances self-awareness and helps supervisors identify areas for improvement [35]. Moreover, training programmes that incorporate feedback mechanisms consistently yield better outcomes compared to those that do not [89]. Therefore, further investigation into training interventions that include upward feedback is of paramount importance.

- The third is the managerial practices to reduce psychosocial risk exposure (MPRPRE) framework proposed by St-Hilarie and colleagues [45]. Criticising the MCPARS for lack of definition of “concrete managerial behaviours”, the authors identified a taxonomy of 92 behaviours grouped into 24 competencies, clustered in eight broad themes. The first theme identified was “supervisory practices”. This consists of seven different competencies (deciding, developing competencies and career, assisting in the task, managing the workload, organising the work, managing working time and holidays and appreciating and recognising work). This theme includes specific practices, such as redistributing workload, supporting skills acquisition, and solving problems quickly. The second theme was “relational practices”, which consisted of three competencies (interacting, initiating relationships, and demonstrating social sensitivity). Some behaviours identified were being cordial, providing emotional support and caring about subordinates’ state. The third theme of “informational practices” involves dialoguing and promoting participation, disseminating and expressing competencies. This includes specific managerial practices such as taking subordinates’ points, notifying them of his/her presence and explaining decisions. Furthermore, “assignment practices” was the fourth theme identified by the authors. This theme includes the competencies of appointing empowering and comprising behaviours such as delegating the execution of the task and requesting formulation of solutions. The competencies of participating (i.e., working with subordinates on the task), coordinating (i.e., consulting one’s immediate manager) and supporting (i.e., helping subordinates with his or her task) were clustered under the fifth theme, “cooperation practices”. The competence of promoting a positive climate (i.e., encouraging mutual aid within the team) and representing (i.e., defending subordinates’ acts to other authorities) was clustered under the sixth theme, “team management practices”. Inside the theme, “leadership practices” were clustered, including the competence of influencing (i.e., striving to obtain resources) and having a vision (i.e., sharing objectivities). Lastly, demonstrating integrity (i.e., being transparent) and demonstrating equity (i.e., treating all subordinates equitably) were clustered with the theme “ethical practices”. Notably, there is a remarkable overlap between St-Hilarie’s framework and MCPARS exits. Among the twelve sub-competencies of MCPARS’ framework [24], seven correspond to those identified by the MPRPRE (e.g., MCPARS’s “problem-solving” and “participating/empowering” with MPRPRE’ “deciding” and “appointing” or “empowering) make it possible to define the MPRPRE’s competency framework broader than MCPARS [45]. However, a lack of a validated instrument to measure the competencies identified by the third approach limited its practical and research applications. Thus, no evidence is present in the literature.

- More recently, in response to the increasing prevalence of remote work arrangements and the widespread adoption of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in the workplace [90], the digital stress-preventive management competencies (DMCs) were conceptualised, identified, and operationalised through the development of a 9-item measurement tool employing Likert-type scale [79]. First, these were defined as “the consolidated supervisors’ competencies of planning, organising, setting objectives, creating and monitoring systems able to optimise a positive psychosocial work environment for remote workers, by organising, communicating and managing work via ICT-mediated interactions” ([46], p. 4) Then, the authors employed a mixed-method, multisource approach, combining expert interviews, literature review, content analysis, factorial analysis, and structural equation modelling, to develop and test a conceptual model of two DMCs affecting four distinct psychosocial factors of the management Standards approach (i.e., superior support, role, demands, control). The first competence, Supportive ICT-Mediated Interaction (SIMI), was associated with superior support and role. It refers to a supervisor’s ability to communicate effectively via ICTs, selecting appropriate digital tools based on the objectives and situational needs. However, it also includes providing clear, timely, and constructive feedback and ensuring availability for urgent matters. Remarkably, this competency shares a significant conceptual overlap with the MCPARS competency of Managing and Communicating Existing and Future Work [46]. The second competency, Avoidance of Abusive ICT Adoption (AAIA), was associated with demands and control. It reflects a supervisor’s ability to use ICTs appropriately and responsibly, ensuring that digital communication does not intrude on employees’ personal time or create an excessive monitoring culture. This includes refraining from sending emails or making unexpected work-related calls outside of working hours—such as during holidays, late at night, or when employees are on sick leave—unless strictly necessary for an emergency. Furthermore, it involves avoiding overly controlling behaviours, such as excessively monitoring remote employees’ activities. Findings on a sample of Italian public administration remote workers indicate that AAIA was strongly associated with lower job demands and even more significantly with higher perceptions of job autonomy and control among remote workers. In contrast, SIMI was associated with superior support and role clarity.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

To date, we can conclude that the stress-preventive management competencies’ approach to study and intervene on the leader-follower dynamics is characterised by many strengths and limits.

One of the main strengths of this approach is its focus on prevention as a means to enhance health and well-being outcomes. By investigating the supervisors’ competencies in the communication, organisation and design of the work that might affect the psychosocial factors’ perceptions of workers, these approaches considered stress management as a part of daily general management activities for supervisors. This preventive approach emphasises proximal outcomes, such as the psychosocial work environment, rather than distal outcomes, such as employee health and well-being. This distinction reduces the expectation for managers to engage in additional extra-role behaviours. Additionally, management competencies are defined as a collection of behaviours in teams of functional to improve and dysfunctional to avoid. This establishes a foundation for a clear understanding among all stakeholders involved in research and practices, such as managers, employers, and human resources practitioners. This clarity can facilitate the seamless transfer of insights within organisational interventions. Furthermore, the behavioural focus also suggests a methodological strength. By measuring the daily behaviours to assess latent constructs (i.e., competencies), rather than concentrating on supervisors’ attitudes or intentions, these approaches should be less subject to bias in competencies’ measurement.

Overall, the focus on prevention and behaviours that characterise these frameworks may promote a more “business-friendly” application of their core principles. Nonetheless, the current literature is quite the opposite. Despite these advantages, the practical implementation of stress-preventive management competencies remains limited. While frameworks have been developed and tested, their application in real-world settings is still scarce. The lack of large-scale intervention studies makes assessing their long-term impact on employee well-being and organisational outcomes difficult. The only noteworthy studies to date are those which employed the MCPARS approach, such as Donaldson-Fedler et al. [44] in the UK, Adachi et al. [87] in Japan, and Toderi et al. [88] in Italy. The findings suggest that supervisors are generally enthusiastic about participating in this type of training and tend to perceive themselves as more competent afterward. However, observable team-level changes are mostly evident when managers begin from low competence levels and are exposed to upward feedback.

Additionally, the sheer number of behaviours associated with each framework—63 in the Gilbreath and Benson model, 66 in MCPARS, and 92 in MPRPRE—raises concerns about practical feasibility. Simplifying and refining these models into more concise, actionable frameworks could enhance their usability in organisational contexts, as has been done with the MCPARS questionnaire [82]. Furthermore, limited available frameworks hampers discussions and comparisons regarding stress-preventive management competencies. Even if there is a significant overlap between existing approaches [45,46], it suggests that these frameworks have investigated the same underlying constructs.

Several avenues for future research and practice emerge from this review. First, longitudinal intervention research is required to evaluate the causal impact of the change in stress-preventive management competencies on proximal outcome, such as the psychosocial work environment, and distal outcomes, such as employees’ well-being, job satisfaction, and organisational performance. While preliminary evaluations suggest positive outcomes, robust longitudinal designs—with pre/post assessments, control groups or experimental conditions comparison, and multi-source data—are necessary to establish the effectiveness and sustainability of these interventions. Future research should also consider process variables, such as perceived organisational support and the perceived usefulness of the training, which can influence both participation and outcomes. Second, cross-cultural research is warranted to examine the extent to which stress-preventive management competencies are universally applicable or context-dependent. Cultural dimensions may substantially influence how managerial behaviours are enacted, interpreted, and valued within organisations. These contextual variables can shape not only the expression of competencies by supervisors, but also how employees perceive and respond to such behaviours. Similarly, sector-specific dynamics, such as those distinguishing public from private management, can further modulate the applicability and salience of stress-preventive competencies [91]. A deeper understanding of these contextual contingencies is essential to ensure the cultural and organisational alignment of leadership development initiatives. Third, future studies should explore individual differences among managers in adopting stress-preventive behaviours. While some supervisors may naturally exhibit these competencies, others may require targeted training and behavioural coaching. Identifying the barriers and facilitators to adopting these competencies could help organisations design more tailored interventions.

To conclude, stress-preventive management competencies represent a promising yet underutilised approach to reducing work-related stress and improving organisational well-being. By focusing on concrete managerial behaviours, these frameworks offer a practical and evidence-based strategy for fostering healthier workplaces. However, their widespread adoption requires further empirical validation, streamlined application, and integration into broader leadership development initiatives. Future research and practice must work together to bridge the gap between theory and implementation, ensuring that managers are equipped with the necessary skills to create a sustainable, stress-resilient work environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization G.C. and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation G.C.; writing—review and editing C.B. and S.T.; supervision C.B. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Treccani Dictionary. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/stress/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Oxford English Dictionary. Available online: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/stress_n?tl=true&tab=etymology (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Selye, H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature 1936, 32, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life; New York Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.; Griffiths, A.; Rial-González, E. Research on Work-Relate Stress. Report for EU-OSHA. 2000. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/report-research-work-related-stress (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- James, K.A.; Stromin, J.I.; Steenkamp, N.; Combrinck, M.I. Understanding the relationships between physiological and psychosocial stress, cortisol and cognition. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1085950. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Figueiredo, I.; Umeoka, E.H.L. Stress: Influences and Determinants of Psychopathology. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1026–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process; Mc Grew-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.R.P.; Caplan, R.D.; van Harrison, R. The Mechanisms of Job Stress and Strain; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office (ILO). Workplace Stress: A Collective Challenge. 2016. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_466547.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Burman, R.; Goswami, T.G. A systematic literature review of work stress. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 3, 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, P.A.; Sauter, S.L.; Pandalai, S.P.; Tiesman, H.M.; Chosewood, L.C.; Cunningham, T.R.; Howard, J. An urgent call to address work-related psychosocial hazards and improve worker well-being. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2024, 67, 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, J.; Graversen, B.K.; Hansen, K.S.; Madsen, I.E.H. The labor market costs of work-related stress: A longitudinal study of 52,763 Danish employees using multi-state modeling. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2024, 50, 61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on Mental Health at Work. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240053052 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.R.; Visockaite, G.; Dewe, P.; Cox, T. The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, F.; Heponiemi, T.; Pavlova, M.; Zaffina, S.; Magnavita, N. Psychosocial risk prevention in a global occupational health perspective: A descriptive analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, S.; Jain, A.; World Health Organization. Health Impact of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: An Overview; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, H.; Villaume, K.; Von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Palm, K. Managing implementation: Roles of line managers, senior managers, and human resource professionals in an occupational health intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.; Yarker, J.; Munir, F.; Bültmann, U. IGLOO: An integrated framework for sustainable return to work in workers with common mental disorders. Work Stress 2018, 32, 400–417. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.; Taris, T.W.; Cox, T. The future of organizational interventions: Addressing the challenges of today’s organizations. Work Stress 2010, 24, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Nayani, R.; Tregaskis, O.; Daniels, K. Sustaining and embedding: A strategic and dynamic approach to workplace wellbeing. In Wellbeing at Work in a Turbulent Era; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 162–178. [Google Scholar]

- Quick, J.; Wright, T.; Adkins, J.; Nelson, D.; Quick, J. Preventive Stress Management in Organizations, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F. Stress lavoro-correlato: Questioni aperte e direzioni future. G. Ital. Psicol. 2019, 46, 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbreath, B. Creating healthy workplaces: The supervisor’s role. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, L., Robertson, I.T., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 19, pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yarker, J.; Donaldson-Feilder, E.; Lewis, R.; Flaxman, P. Management Competencies for Preventing and Reducing Stress at Work: Identifying and Developing the Management Behaviors Necessary to Implement the HSE Management Standards; HSE Books: London, UK, 2007; p. 126. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr553.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Yarker, J.; Lewis, R.; Donaldson-Feilder, E. Management Competencies for Preventing and Reducing Stress at Work: Identifying the Management Behaviors Necessary to Implement the Management Standards: Phase Two; HSE Books: Sheffield, UK, 2008; p. 109. Available online: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/28227/1/Lewis-R-18716.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, V.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnesen, L.; Pihl-Thingvad, S.; Winter, V. The contagious leader: A panel study on occupational stress transfer in a large Danish municipality. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Toderi, S.; Gaggia, A.; Balducci, C.; Sarchielli, G. Reducing psychosocial risks through supervisors’ development: A contribution for a brief version of the ‘Stress Management Competency Indicator Tool’. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 518–519, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, C.; Karanika-Murray, M.; Hasson, H. Intervention leadership: A dynamic role that evolves in tandem with the intervention. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2018, 11, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarker, J.; Donaldson-Feilder, E.; Lewis, R. Management competencies for health and wellbeing. In Handbook on Management and Employment Practices; Brough, P., Gardiner, E., Daniels, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Barling, J. Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 2010, 24, 260–279. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Murphy, L.D.; Zacher, H. A systematic review and critique of research on ‘healthy leadership’. Leadersh. Q. 2020, 31, 101335. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound; EU-OSHA. Psychosocial Risks in Europe: Prevalence and Strategies for Prevention. 2014. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2014/psychosocial-risks-europe-prevalence-and-strategies-prevention (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Day, D.V.; Fleenor, J.W.; Atwater, L.E.; Sturm, R.E.; McKee, R.A. Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, B.; Reichard, R.J.; Batistič, S.; Černe, M. A bibliometric review of the leadership development field: How we got here, where we are, and where we are headed. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101381. [Google Scholar]

- Training Industry. The Leadership Training Market. 2020. Available online: https://trainingindustry.com/wiki/leadership/the-leadership-training-market (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- An, S.H.; Meier, K.J.; Bøllingtoft, A.; Andersen, L.B. Employee perceived effect of leadership training: Comparing public and private organizations. Int. Public Manag. J. 2019, 22, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.B.; Andersen, L.B.; Bøllingtoft, A.; Eriksen, T.L.M. Can leadership training improve organizational effectiveness? Evidence from a randomized field experiment on transformational and transactional leadership. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 82, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidle, B.; Fernandez, S.; Perry, J.L. Do leadership training and development make a difference in the public sector? A panel study. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Hasson, H.; Tafvelin, S. Leadership training as an occupational health intervention: Improved safety and sustained productivity. Saf. Sci. 2016, 81, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, M.M.; Schwarz, U.V.T.; Hellgren, J.; Hasson, H.; Tafvelin, S. Leading for safety: A question of leadership focus. Saf. Health Work 2019, 10, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbreath, B.; Benson, P.G. The contribution of supervisor behaviour to employee psychological well-being. Work Stress 2004, 18, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson-Feilder, E.; Yarker, J.; Lewis, R. Preventing Stress: Promoting Positive Manager Behavior. 2009. Available online: https://www.cipd.org/globalassets/media/knowledge/knowledge-hub/reports/preventing-stress_2009-promoting-positive-manager-behaviour_tcm18-16794.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- St-Hilaire, F.; Gilbert, M.H.; Lefebvre, R. Managerial practices to reduce psychosocial risk exposure: A competency-based approach. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2018, 35, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, G.; Balducci, C.; Toderi, S. Digital stress-preventive management competencies: Definition, identification and tool development for research and practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, C.R.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Madsen, I.E. Fifty years of research on psychosocial working conditions and health: From promise to practice. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2024, 50, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Lawler, E.E. Employee reactions to job characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Work Redesign; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.A. Taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar]

- Vleeshouwers, J.; Fløvik, L.; Christensen, J.O.; Johannessen, H.A.; Bakke Finne, L.; Mohr, B.; Lunde, L.K. The relationship between telework from home and the psychosocial work environment: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 2025–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.O.; Finne, L.B.; Garde, A.H.; Nielsen, M.B.; Sørensen, K.; Vleeshouwers, J. The influence of digitalization and new technologies on psychosocial work environment and employee health: A literature review. In STAMI-Rapport; STAMI: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rugulies, R. What is a psychosocial work environment? Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2019, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Rosenman, R.H.; Carroll, V.; Tat, R.J. Changes in the serum cholesterol and blood clotting time in men subjected to cyclic variation of occupational stress. Circulation 1958, 17, 852–861. [Google Scholar]

- Gardell, B. Psychosocial aspects of industrial product methods. In Society, Stress and Disease; Levi, L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1981; Volume 4, pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser, M.; Gardell, B. Underload and overload in working life: Outline of a multidisciplinary approach. J. Hum. Stress 1976, 2, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gardell, B. Scandinavian research on stress in working life. Int. J. Health Serv. 1982, 12, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kornhauser, A. Mental Health of the Industrial Worker; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, I.E.; Rugulies, R. Understanding the impact of psychosocial working conditions on workers’ health: We have come a long way, but are we there yet? Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.; Cox, T.; Cosmar, M.; Gründler, R.; Flemming, D.; Van den Broek, K. Calculating the Cost of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks. European Agency for Safety and Helath at Work. 2014. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/calculating-cost-work-related-stress-and-psychosocial-risks (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Cousins, R.; MacKay, C.J.; Clarke, S.D.; Kelly, C.; Kelly, P.J.; McCaig, R.H. ‘Management Standards’ work-related stress in the UK: Practical development. Work Stress 2004, 18, 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, C.J.; Cousins, R.; Kelly, P.J.; Lee, S.; McCaig, R.H. ‘Management Standards’ and work-related stress in the UK: Policy background and science. Work Stress 2004, 18, 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard, M.; Skinner, N.; Tuckey, M.R.; Bailey, T. National surveillance of psychosocial risk factors in the workplace: An international overview. Work Stress 2007, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Toderi, S.; Cioffi, G.; Yarker, J.; Lewis, R.; Houdmont, J.; Balducci, C. Manager–team (dis)agreement on stress-preventive behaviours: Relationship with psychosocial work environment and employees’ well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toderi, S.; Balducci, C. Stress-preventive management competencies, psychosocial work environments, and affective well-being: A multilevel, multisource investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, J.F.; Kelley, R.F. The psychological climate and reported well-being of underground miners: An exploratory study. Hum. Relat. 1978, 31, 567–581. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, A. Halsopromotion i Arbetslivet; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnl, A.; Seubert, C.; Rehfuess, E.; von Elm, E.; Nowak, D.; Glaser, J. Human resource management training of supervisors for improving health and well-being of employees. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD010905. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association’s Dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/competence (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Boyatzis, R.E. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, L.; Gilbreath, B.; Kim, T.Y.; Grawitch, M.J. Come rain or come shine: Supervisor behavior and employee job neglect. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2014, 35, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbreath, B.; Karimi, L. Supervisor behavior and employee presenteeism. Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2012, 7, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, M.; Yang, S.-W. Likert-Type Scale. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderi, S.; Sarchielli, G. Psychometric properties of a 36-item version of the “stress management competency indicator tool”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdmont, J.; Jachens, L.; Randall, R.; Colwell, J.; Gardner, S. Stress Management Competency Framework in English policing. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Carluccio, F.; Colledani, D.; Falco, A. Positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance: The serial mediation of workplace spirituality and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenevert, M.; Vignoli, M.; Conway, P.M.; Balducci, C. Workplace bullying and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology: The influence of role conflict and the moderating effects of neuroticism and managerial competencies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvoni, S.; Biron, C.; Gilbert, M.H.; Dextras-Gauthier, J.; Ivers, H. Managing virtual presenteeism during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multilevel study on managers’ stress management competencies to foster functional presenteeism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, H.; Sekiya, Y.; Imamura, K.; Watanabe, K.; Kawakami, N. The effects of training managers on management competencies to improve their management practices and work engagement of their subordinates: A single group pre-and post-test study. J. Occup. Health 2020, 62, e12085. [Google Scholar]

- Toderi, S.; Cioffi, G.; Yarker, J.; Lewis, R.; Houdmont, J.; Balducci, C. Developing stress-preventive management competencies: An evaluation of the mechanism and the process in a training experience. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerenza, C.N.; Reyes, D.L.; Marlow, S.L.; Joseph, D.L.; Salas, E. Leadership training design, delivery, and implementation: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1686–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Türkes, M.C.; Vuta, D.R. Telework: Before and after COVID-19. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1370–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, S.; Nørgaard, R.R.; Tangsgaard, E.R.; Winsløw, M.A.; Østergaard-Nielsen, M.R. Public and private management: Now, is there a difference? A systematic review. Int. Public Manag. J. 2024, 27, 109–142. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).