Inclusive Supervision: Bridging the Cultural Divide

Abstract

1. Introduction

We do not leave our identities as raced, classed and gendered bodies outside the door when we engage in supervision: instead, our personal histories, experiences, cultural and class backgrounds and social, cultural and national locations remain present (some might say omnipresent). Culture, politics and history matter in supervision.[9] (p. 368)

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Themes

3.1.1. Power Dynamics and Feedback

3.1.2. Lack of Belonging and Support

3.1.3. Racial Lens and Academic Competence

3.1.4. (Mis)understanding Cultural Differences

3.1.5. Communication and Language Barriers

4. Discussion

They may remind each other of former significant others (and in some sense there are others present in the supervision meeting), of themselves even. They may feel strong feelings of gratitude, resentment, frustrations, disappointment, because of these remindings.[28]

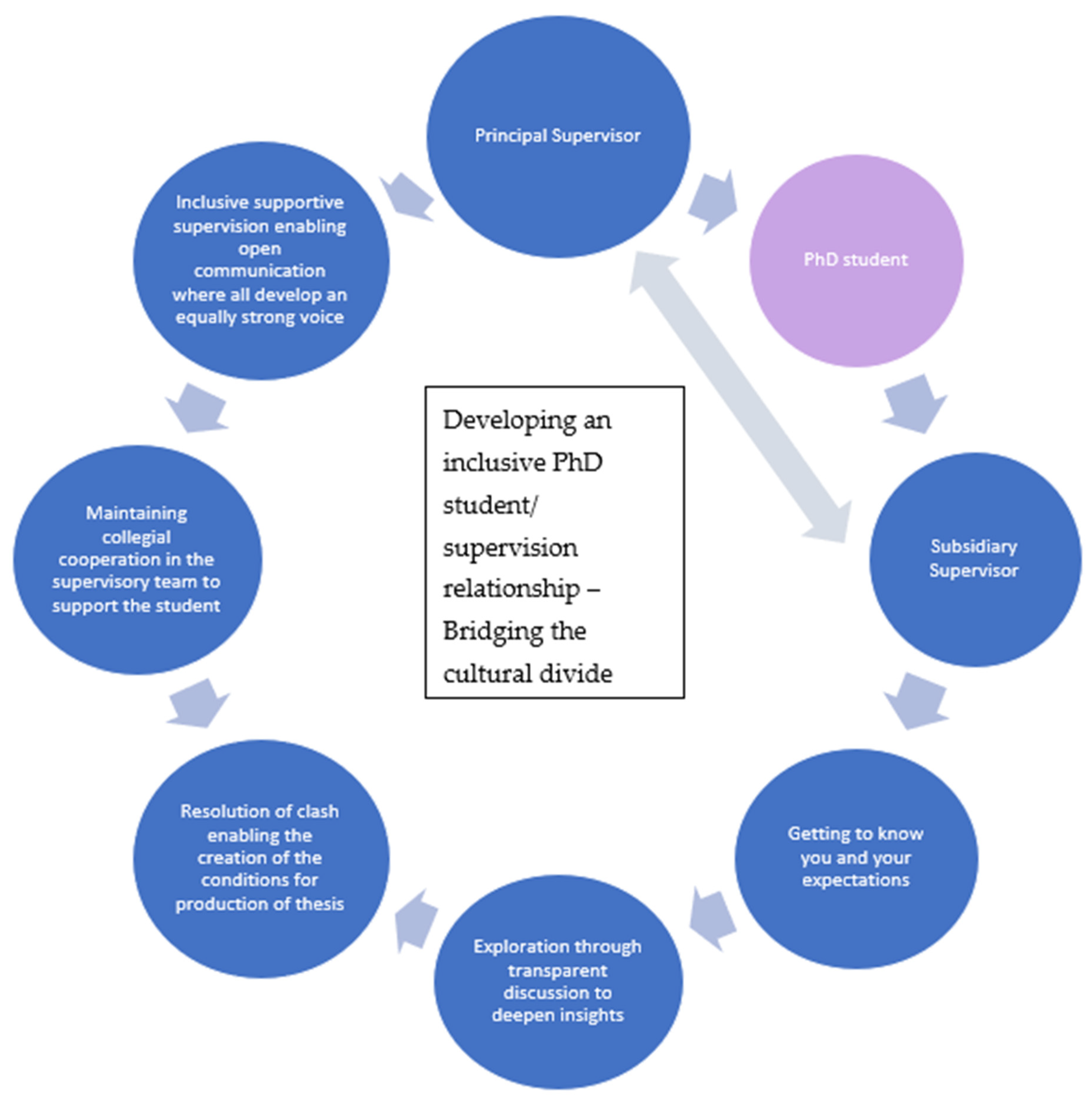

4.1. Inclusive PhD Supervision

4.2. Core Themes of Inclusive Supervision

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, A.B.; McCallum, C.M.; Shupp, M.R. Inclusive Supervision in Student Affairs: A Model for Professional Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, E. A model of research group microclimate: Environmental and cultural factors affecting the experience of overseas research students in the UK. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, A.S. The Role of Supervisor-Supervisee Cultural Differences, Supervisor Multicultural Competence and the Supervisory Working Alliance in Supervision Outcomes: A Moderation Mediation Model. Ph.D. Thesis, Old Dominian University, Norfolk, VA, USA, 2011. Available online: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1041&context=chs_etds (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Sidhu, G.K.; Kaur, S.; Fook, C. Postgraduate supervision: Comparing student perspectives from Malaysia and the United Kingdom. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 123, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, S.; Brady, J. Supervising Postgraduate Researchers. Available online: https://inclusiveteaching.leeds.ac.uk/resources/teaching-inclusively/supervising-postgraduate-researchers/ (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Manathunga, C.; Pitt, R.; Crtichley, C. Graduate attribute development and employment outcomes: Tracking PhD graduates. Assess. Eval. High. Edu. 2009, 34, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dericks, G.; Thompson, E.; Roberts, M.; Phua, F. Determinants of PhD student satisfaction: The roles of supervisor, department and peer qualities. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlik, A.; Hall, N.; McAlpine, L.; Hubbard, K. The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students’ completion, achievement, and well-being. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2018, 13, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manathunga, C. Moments of transculturation and assimilation: Post-colonial explorations of supervision and culture. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2011, 48, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, C.; Michaud, A.; Thuku, M.; Skidmore, B.; Stevens, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Garritty, C. Defining systematic reviews: A systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 129, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, V.J.; Stevens, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Kamel, C.; Garritty, C. Performing rapid reviews. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitat?>Mive-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Edwards, A.; Elwyn, G.; Hood, K.; Rollnick, S. Judging the ‘weight of evidence’ in systematic reviews: Introducing rigour into the qualitative overview stage by assessing signal and noise. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2000, 6, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.J.; Crabtree, B.F. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Setta, A.M.; Jeyaraman, M.; Attia, A.; Al-Inany, H.G.; Ferri, M.; Ansari, M.T.; Garritty, C.M.; Bond, K.; Norris, S.L. Methods for developing evidence reviews in short periods of time: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2016, 12, e0172372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alebaikan, R.; Bain, Y.; Cornelius, S. Experiences of distance doctoral supervision in cross-cultural teams. Teach. High. Educ. 2023, 28, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, D.L.; Kobayashi, S. How can PhD supervisors play a role in bridging academic cultures? Teach. High. Educ. 2019, 24, 911–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidman, J.; Manathunga, C.; Cornforth, S. Intercultural PhD supervision: Exploring the hidden curriculum in a social science faculty doctoral programme. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 1208–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, S.; Haque, E. The struggle to make sense of doctoral study. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 34, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S. Racism in academia: (How to) stay Black, sane, and proud as the doctoral supervisory relationship implodes. In The International Handbook of Black Community Mental Health; Majors, R., Carberry, K., Ransaw, T.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mattocks, K.; Briscoe-Palmer, S. Diversity, inclusion and doctoral study: Challenges facing minority PhD students in the United Kingdom. Eur. Political Sci. 2016, 15, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomnian, S. Thai PhD students and their supervisors at an Australian University: Working relationship, communication and agency. PASAA J. Lang. Teach. Learn. Thail. 2017, 53, 26–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, S.; Araujo e Sa, M.H. Researching across languages and cultures: A study with doctoral students and supervisors at a Portuguese University. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2020, 10, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester-Seeto, T.; Homewood, J.; Thogersen, J.; Jacenyik-Trawoger, C.; Manathunga, C.; Reid, A.; Holbrook, A. Doctoral supervision in a cross-cultural context: Issues affecting supervisors and candidates. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamont, S.; Atkinson, P. Doctoring uncertainty: Mastering craft knowledge. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2001, 31, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B. Class, Codes and Control, Volume 3: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions; Routledge and Paul: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, S.; Hill, T.; Black, E. Thesis supervision in the social sciences: Managed or negotiated? High. Educ. 1994, 28, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, B. Walking on a rickety bridge: Mapping supervision. In Proceedings of the HERSDA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12–15 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Showunmi, V. Visible, invisible: Black women in higher education. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinity College Dublin. Available online: https://www.tcd.ie/graduatestudies/students/research/supervision/ (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Showunmi, V. The importance of intersectionality in higher education and educational leadership research. J. High. Educ. Policy Leadersh. Stud. 2020, 1, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahamaki, M.; Saru, E.; Palmunen, L.-M. Doctoral supervision as an academic practice and leader-member relationship: A critical approach to relationship dynamics. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D. Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Stud. High. Educ. 2007, 31, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Handley, K.; Millar, J.; O’Donovan, B. Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; Hartley, P.; Skelton, A. The conscientious consumer: Reconsidering the role of assessment feedback in student learning. Stud. High. Educ. 2002, 27, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.; Marshall, J.A.; Gordon, L.L. Racial and gender bias in supervisory evaluation and feedback. Clin. Superv. 2001, 20, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showunmi, V.; Tomlin, C. Understanding and Managing Sophisticated and Everyday Racism: Implications for Education and Work; Lexington Books: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Statistics Agency. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/17-01-2023/higher-education-staff-statistics-uk-202122-released (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Bridge Group Research Action Equality. Available online: https://www.thebridgegroup.org.uk/blog-posts/2023/04/20/social-backgrd-academics (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Henry, F.; Tator, C. Racism in the Canadian University. Demanding Social Justice, Inclusion and Equity; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A.J.; Mendoza-Denton, R.; Patt, C.; Young, I.; Eppig, A.; Garrell, L.R.; Rees, C.D.; Nelson, T.W.; Richards, M.A. Structure and belonging: Pathways to success for underrepresented minority and women PhD students in STEM fields. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e020927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C. “Peering through the window looking in”: Postgraduate experiences of non-belonging and belonging in relation to mental health and wellbeing. Stud. Grad. Postdr. Educ. 2021, 12, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruedas-Gracia, N.; Botham, C.M.; Moore, A.R.; Peña, C. Ten simple rules for creating a sense of belonging in your research group. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, J.P. The application of a model of turnover in work organisations to the student attrition process. Rev. High. Educ. 1983, 6, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Aims | Country | Sample | Method | Complete or Partial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alebaikan et al., 2020 [16] | To explore opportunities and challenges associated with distance and cross-cultural PhD supervision | Saudi Arabia | Three female Saudi students and five PhD supervisors | Student logs, interviews with students and supervisors, reflexive dialogue | Complete |

| Elliot & Kobayashi, 2019 [17] | To examine the cross-cultural facets of PhD supervision | Denmark | Six pairs of international PhD students and supervisors | Interviews | Complete |

| Kidman et al., 2017 [18] | To explore the experiences of international PhD students during the first two years of their doctoral studies. | New Zealand | 12 PhD students | Three 1–1 interviews and two focus groups | Partial study—only included findings related to inclusive supervision |

| Acker and Haque, 2015 [19] | Explore narratives of stress and struggle of PhD students | Canada | 27 PhD students | Interviews | Partial study—focused on findings relevant to inclusive supervision |

| Walker, 2020 [20] (book chapter) | To provide a reflexive account of three PhD students’ experience of racism in their supervisory relationship | UK | 3 PhD students | Reflexive narrative | Complete |

| Mattocks and Briscoe-Palmer, 2016 [21] | To examine barriers/challenges faced by women, Black minority ethnic (BME) groups, and students living with a disability throughout their PhD studies | UK | 70 PhD students | Interviews | Partial—only those findings relevant to inclusive supervision |

| Nomnian, 2017 [22] | To explore practices that impact Thai students’ experiences during their PhD supervision | Australia | 9 PhD students | Interviews, qualitative case study | Complete |

| Pinto et al., 2020 [23] | To explore PhD research experience across languages and cultures | Portugal | 12 PhD students and four supervisors | Interviews | Partial—only findings relevant to inclusive supervision |

| Winchester-Seeto et al., 2014 [24] | To explore experiences of doctoral supervision in a cross-cultural context | Australia | 46 PhD students and 38 Supervisors | Interviews | Complete |

| No. | Theme | Frequency | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Power dynamics and feedback | 6 | This theme centered on the expectations around the supervisor’s feedback and the challenges associated with this. The power imbalance between supervisor and supervisee was highlighted, especially in expressing disagreements. |

| 2 | Lack of belonging and support | 5 | This theme focused on a lack of belonging experienced by ethnic minority PhD students, many of whom were also international students. It also captured the experiences of some students who felt that they did not receive adequate emotional or pastoral support from their PhD supervisors. |

| 3 | Racial lens and academic competence | 4 | This theme captured PhD supervisors’ views on some international students' lack of academic competence. PhD students express potential unconscious racism and stereotyping by supervisors. |

| 4 | (Mis)understanding cultural differences | 3 | The behaviors associated with cross-cultural exchanges are emphasized in this theme, and some students discuss the challenges associated with modifying these cultural behaviors. |

| 5 | Communication and language barriers | 2 | This theme encapsulated both PhD students’ and supervisors’ views on challenges with verbal and non-verbal communication and corresponding support. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Showunmi, V.; Younas, F.; Gutman, L.M. Inclusive Supervision: Bridging the Cultural Divide. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 186-200. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4010016

Showunmi V, Younas F, Gutman LM. Inclusive Supervision: Bridging the Cultural Divide. Encyclopedia. 2024; 4(1):186-200. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleShowunmi, Victoria, Fatima Younas, and Leslie Morrison Gutman. 2024. "Inclusive Supervision: Bridging the Cultural Divide" Encyclopedia 4, no. 1: 186-200. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4010016

APA StyleShowunmi, V., Younas, F., & Gutman, L. M. (2024). Inclusive Supervision: Bridging the Cultural Divide. Encyclopedia, 4(1), 186-200. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4010016