Use of Effective Feedback in Veterinary Clinical Teaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What Is Feedback and Its Purpose in Veterinary Medical Education

Types of Feedback

3. Barriers to Efficacy of the Provided Feedback

| Area of Feedback | Parameter | References |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback content/context | Addressing issues that cannot be corrected, volume of information (e.g., overwhelming) | [16,38,43] |

| Assessment/Summative information rather than coaching, lacking intervention plan | [5,6,15,16,18,19,27,51] | |

| Attempts to interpret learners’ intentions rather than stating facts, insensitive, mismatch in the quality of provided/received feedback | [39] | |

| Focus on learner/personality traits rather than performance, unidirectional (instructor-based) | [5,6,15,18,19,28,39,43] | |

| generic (e.g., not based on direct observation, not addressing specific competency), nontailored, inconsistent, late | [5,15,18,19,21,26,27,28,36,38,39,43,52,57] | |

| Feedback delivery/environment | Communication issues (e.g., language primarily composed of adjectives and adverbs, technical language, English as a second language) | [5,6,15,18,19,39,52] |

| Difference in age, culture (including lack of ‘feedback culture’) | [43,57] | |

| Difference in power, no established learner–instructor relationship, proud maintenance of hierarchy | [8,11,16,19,27,31,43,49,52,57] | |

| Not suitable for provision of feedback (e.g., confrontational furniture setting, not ensuring confidentiality) | [5,13,18,19,22,50] | |

| Overall learning environment not supportive of the feedback process, stressful clinical environment, time constraints, workload issues | [8,13,16,17,22,26,43] | |

| Instructor (Provider) | Belief that learners are not interested in receiving effective feedback in improving their performance and are only concerned about the grade, cognitive biases (e.g., ‘halo’ effect, unconscious bias) | [2,18,37] |

| Insufficient baseline knowledge of the instructor, lack of experience/expertise in providing feedback, lack of training in the provision of effective feedback, being dishonestly kind when there is need of improvement | [3,19,21] | |

| Difference in the perception what constitutes effective feedback, inadequate attitude, poor availability to learners, incongruity with the learner’s perception of feedback | [2,5,11,20,22,33,47,48,57] | |

| Fear of interpersonal tension in instructor–learner relationship | [5,11,13,15,19,20,22,28,43,48,58] | |

| Fear of emotional reaction by the learner, fear of retaliation | [2,5,7,8,13,14,15,18,19,28,29,43,48,52,57,58] | |

| Preventing learner-centered approach to feedback, inappropriate language/expression | [8,18,50,52] | |

| Unknown expectations (e.g., no mutually agreed-upon learning outcomes, poor curriculum knowledge), lack of direct observation | [18,38] | |

| Learner (Receiver) | ‘Halo’ effect (cognitive bias, in which overall impression changes perception towards favorably perceived learners) | [17,19] |

| Incongruity with the instructor’s perception of feedback, lack of recognition feedback has been provided, unknown expectations (e.g., no mutually agreed-upon learning outcomes) | [2,5,7,13,14,15,16,18,20,22,29,33,38,48] | |

| Lack of self-awareness/efficacy, lack of psychological safety to contradict feedback information, early in training | [13,48] | |

| Not receptive to feedback, emotional state, overconfidence, personal disposition | [5,13,18,43,52] |

3.1. Elements of Effective Feedback

3.2. Who Can Initiate the Feedback Session

3.3. Who Can Provide Feedback to Veterinary Medical Learners

4. Feedback Context (Content and Style of Delivery)

5. Environment for Providing Feedback to Veterinary Medical Learners

6. Instructor

7. Learner

- ‘Experience’, referring to prior experience with feedback. Previous exposure to destructive feedback often results in reluctance to use feedback information [48].

- ‘Identity’, referring to the belief that one’s personal identity is being assaulted [13,17,21]. Perception of this character is often associated with emotional responses. Emotionally charged situations are not conductive to receiving feedback by the learner [17]. In such situations, feedback should be delayed until the emotional charge has subsided.

- ‘Relationship trigger’, referring to the learner–instructor relationship and the learner’s perception of the credibility of the instructor [17].

- ‘Truth trigger’, referring to inability/reluctance of the learner to accept that the feedback information is correct [13,17]. Terms over- and underconfidence are often used to describe this trigger. For example, a mismatch between the provided feedback and self-assessment by the learner (the so-called Dunning–Kruger effect of cognitive bias, in which the learner overestimates their ability in performing a task) [19,39]. Another issue causing this trigger is discordant feedback from a variety of sources. The ‘truth trigger’ becomes more evident with the self-esteem of the ‘Millennial generation’, who see themselves as being special and who lack the ability to self-critique [27].

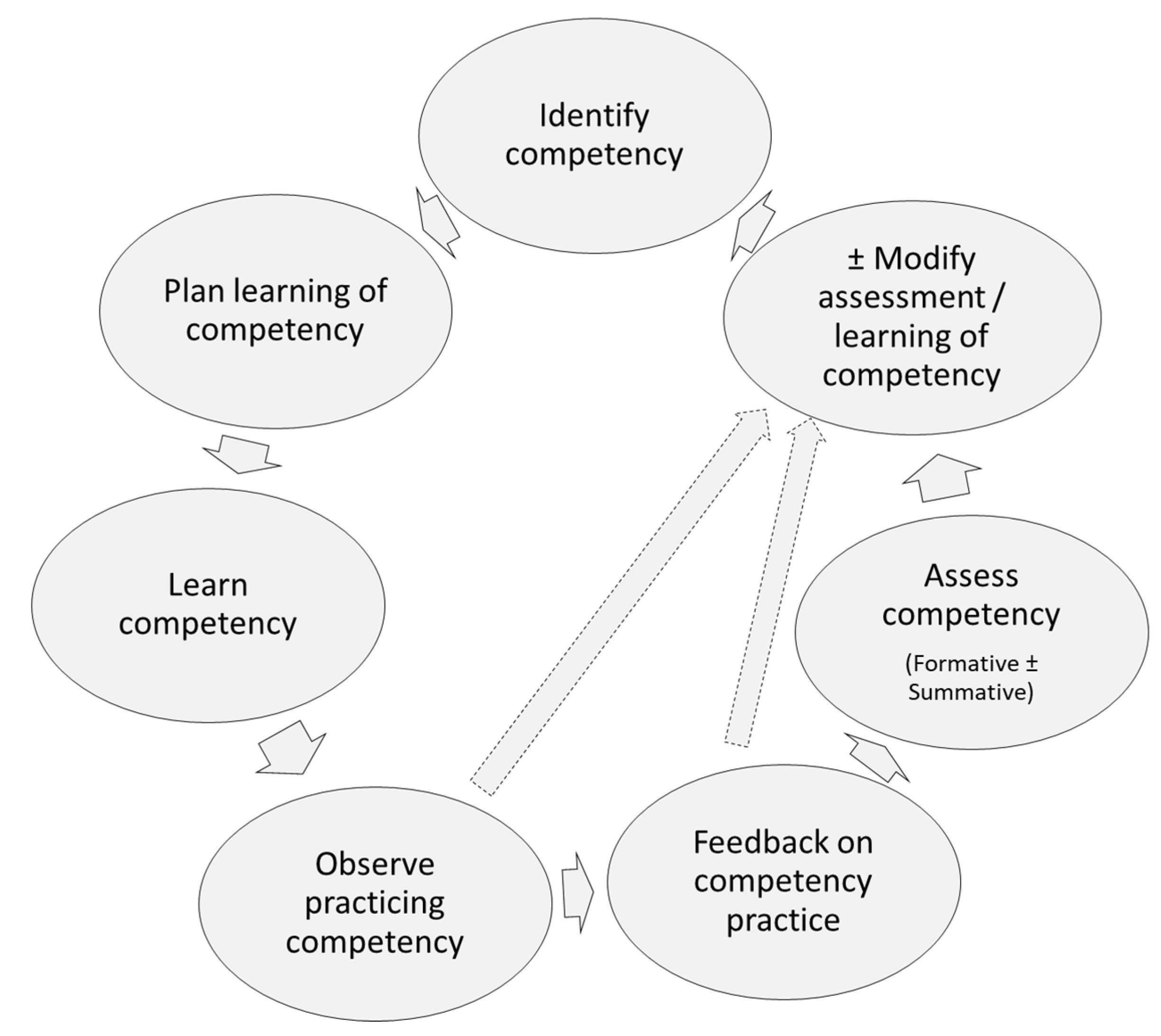

8. Models for Providing Effective Feedback

9. Method for Providing Effective Feedback to Veterinary Medical Learners

10. Discussion

11. Conclusions

12. Glossary of Terms

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carr, A.N.M.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Effective Veterinary Clinical Teaching in a Variety of Teaching Settings. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, L.A.; Oranje, J.; Rich, A.M.; Meldrum, A. Advancing dental education: Feedback processes in the clinical learning environment. J. R. Soc. 2020, 50, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Ofshteyn, A.; Miller, M.; Ammori, J.; Steinhagen, E. “Residents as Teachers” Workshop Improves Knowledge, Confidence, and Feedback Skills for General Surgery Residents. J. Surg. Educ. 2020, 77, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Using the five-microskills method in veterinary medicine clinical teaching. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Cooke, L. Giving effective feedback to psychiatric trainees. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amonoo, H.L.; Longley, R.M.; Robinson, D.M. Giving Feedback. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 2021, 44, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baseer, N.; Mahboob, U.; Degnan, J. Micro-Feedback Training:Learning the art of effective feedback. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 1525–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duijn, C.C.M.A.; Welink, L.S.; Mandoki, M.; ten Cate, O.T.J.; Kremer, W.D.J.; Bok, H.G.J. Am I ready for it? Students’ perceptions of meaningful feedback on entrustable professional activities. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2017, 6, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvey, P.; Radomski, N.; O’Connor, D. Written feedback and continuity of learning in a geographically distributed medical education program. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Watling, C.J.; Brand, P.L.P. Feedback and coaching. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, E.; King, L.; Foy, L.; McLeod, M.; Traynor, J.; Watson, W.; Gray, M. Feedback in clinical practice: Enhancing the students’ experience through action research. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 31, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielson, J.A. Key Assumptions Underlying a Competency-Based Approach to Medical Sciences Education, and Their Applicability to Veterinary Medical Education. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 688457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila-Cervantes, A.; Foulds, J.L.; Gomaa, N.A.; Rashid, M. Experiences of Faculty Members Giving Corrective Feedback to Medical Trainees in a Clinical Setting. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2021, 41, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredette, J.; Michalec, B.; Billet, A.; Auerbach, H.; Dixon, J.; Poole, C.; Bounds, R. A qualitative assessment of emergency medicine residents’ receptivity to feedback. AEM Educ. Train. 2021, 5, e10658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienstock, J.L.; Katz, N.T.; Cox, S.M.; Hueppchen, N.; Erickson, S.; Puscheck, E.E. To the point: Medical education reviews-providing feedback. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokko, H.N.; Gatchel, J.R.; Becker, M.A.; Stern, T.A. The Art and Science of Learning, Teaching, and Delivering Feedback in Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics 2016, 57, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.; Natesan, S.; Breslin, A.; Gottlieb, M. Finessing Feedback: Recommendations for Effective Feedback in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 75, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jug, R.; Jiang, X.S.; Bean, S.M. Giving and receiving effective feedback a review article and how-to guide. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 143, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burns, J.; Chetlen, A.; Morgan, D.E.; Catanzano, T.M.; McLoud, T.C.; Slanetz, P.J.; Jay, A.K. Affecting Change: Enhancing Feedback Interactions with Radiology Trainees. Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29, S111–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, B.M.; O’Neil, A.; Lohse, C.; Heller, S.; Colletti, J.E. Bridging the gap to effective feedback in residency training: Perceptions of trainees and teachers. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey-Murto, S.; Mihok, M.; Pugh, D.; Touchie, C.; Halman, S.; Wood, T.J. Feedback in the OSCE: What Do Residents Remember? Teach. Learn. Med. 2016, 28, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yarris, L.M.; Linden, J.A.; Hern, H.G.; Lefebvre, C.; Nestler, D.M.; Fu, R.; Choo, E.; LaMantia, J.; Brunett, P. Attending and resident satisfaction with feedback in the emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, S76–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthew, S.M.; Bok, H.G.J.; Chaney, K.P.; Read, E.K.; Hodgson, J.L.; Rush, B.R.; May, S.A.; Kathleen Salisbury, S.; Ilkiw, J.E.; Frost, J.S.; et al. Collaborative development of a shared framework for competency-based veterinary education. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2020, 47, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Establishments for Veterinary Education. The Association: Foundation, Mission and Objectives. Available online: https://www.eaeve.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Dooley, L.M.; Bamford, N.J. Peer feedback on collaborative learning activities in veterinary education. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bakke, B.M.; Sheu, L.; Hauer, K.E. Fostering a Feedback Mindset: A Qualitative Exploration of Medical Students’ Feedback Experiences With Longitudinal Coaches. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughness, G.; Georgoff, P.E.; Sandhu, G.; Leininger, L.; Nikolian, V.C.; Reddy, R.; Hughes, D.T. Assessment of clinical feedback given to medical students via an electronic feedback system. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 218, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burgess, A.; van Diggele, C.; Roberts, C.; Mellis, C. Feedback in the clinical setting. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 2280–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.R.; Pelletier, A.; Royce, C.; Goldfarb, I.; Singh, T.; Lau, T.C.; Bartz, D.D. Feedback Focused: A Learner- and Teacher-Centered Curriculum to Improve the Feedback Exchange in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clerkship. MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2021, 17, 11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashizume, C.T.; Hecker, K.G.; Myhre, D.L.; Bailey, J.V.; Lockyer, J.M. Supporting veterinary preceptors in a distributed model of education: A faculty development needs assessment. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2016, 43, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, J.; Schultz, K.; Han, H.; Dalgarno, N. Feedback on feedback: A two-way street between residents and preceptors. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2021, 12, e32–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipnevich, A.A.; Panadero, E. A Review of Feedback Models and Theories: Descriptions, Definitions, and Conclusions. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 720195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruohoniemi, M.; Forni, M.; Mikkonen, J.; Parpala, A. Enhancing quality with a research-based student feedback instrument: A comparison of veterinary students’ learning experiences in two culturally different European universities. Qual. High. Educ. 2017, 23, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Button, B.; Cook, C.; Goertzen, J.; Cameron, E. A Novel, Combined Student and Preceptor Professional Development Session for Optimizing Feedback: Protocol for a Multimethod, Multisite, and Multiyear Intervention. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halman, S.; Dudek, N.; Wood, T.; Pugh, D.; Touchie, C.; McAleer, S.; Humphrey-Murto, S. Direct Observation of Clinical Skills Feedback Scale: Development and Validity Evidence. Teach. Learn. Med. 2016, 28, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacKay, J.R.D.; Hughes, K.; Marzetti, H.; Lent, N.; Rhind, S.M. Using National Student Survey (NSS) qualitative data and social identity theory to explore students’ experiences of assessment and feedback. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2019, 4, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voelkel, S.; Varga-Atkins, T.; Mello, L.V. Students tell us what good written feedback looks like. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gigante, J.; Dell, M.; Sharkey, A. Getting beyond “good job”: How to give effective feedback. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schartel, S.A. Giving feedback—An integral part of education. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2012, 26, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjawi, R.; Bearman, M.; Sheldrake, M.; Brumpton, K.; O’Shannessy, M.; Dick, M.L.; French, M.; Noble, C. The influence of psychological safety on feedback conversations in general practice training. Med. Educ. 2022, 56, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, H.; Kidd-Romero, S.; Brown, R.F.; Kavic, S.M.; Kubicki, N.S. Keep it SIMPL: Improved Feedback After Implementation of an App-Based Feedback Tool. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 1475–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing-You, R.; Ramesh, S.; Hayes, V.; Varaklis, K.; Ward, D.; Blanco, M. Trainees’ Perceptions of Feedback: Validity Evidence for Two FEEDME (Feedback in Medical Education) Instruments. Teach. Learn. Med. 2018, 30, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKimm, J. Giving effective feedback. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2009, 70, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.H.; Lee, S.S.; Yeo, S.P.; Ashokka, B.; Samarasekera, D.D. Developing metacognition through effective feedback. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, P.; Henderson, M.; Mahoney, P.; Phillips, M.; Ryan, T.; Boud, D.; Molloy, E. What makes for effective feedback: Staff and student perspectives. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; Mellis, C. Feedback and assessment for clinical placements: Achieving the right balance. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Malley, E.; Scanlon, A.M.; Alpine, L.; McMahon, S. Enabling the feedback process in work-based learning: An evaluation of the 5 minute feedback form. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkany, D.; Deitte, L. Providing Feedback: Practical Skills and Strategies. Acad. Radiol. 2017, 24, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearne, S. Effective feedback and the educational alliance. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, C.; Sly, C.; Collier, L.; Armit, L.; Hilder, J.; Molloy, E. Enhancing feedback literacy in the workplace: A learner-centred approach. Prof. Pract. Based Learn. 2019, 25, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, P.L.P.; Jaarsma, A.D.C.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M. Driving lesson or driving test?: A metaphor to help faculty separate feedback from assessment. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2021, 10, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstone, N.E.; Nash, R.A.; Parker, M.; Rowntree, J. Supporting Learners’ Agentic Engagement With Feedback: A Systematic Review and a Taxonomy of Recipience Processes. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brukner, H.; Altkorn, D.L.; Cook, S.; Quinn, M.T.; McNabb, W.L. Giving effective feedback to medical students: A workshop for faculty and house staff. Med. Teach. 1999, 21, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olave-Encina, K.; Moni, K.; Renshaw, P. Exploring the emotions of international students about their feedback experiences. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 40, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desy, J.; Busche, K.; Cusano, R.; Veale, P.; Coderre, S.; McLaughlin, K. How teachers can help learners build storage and retrieval strength. Med. Teach. 2018, 40, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, S.; Agrawal, D.; Greenberg, L. The Enhanced Brief Structured Observation Model: Efficiently Assess Trainee Competence and Provide Feedback. MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2021, 17, 11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Ryan, T.; Phillips, M. The challenges of feedback in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillon, P.; Wood, D.; Yardley, S. ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine, 3rd ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gatewood, E.; De Gagne, J.C. The one-minute preceptor model: A systematic review. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2019, 31, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humm, K.R.; May, S.A. Clinical reasoning by veterinary students in the first-opinion setting: Is it encouraged? Is it practiced? J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2018, 45, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kleijn, R.A.M. Supporting student and teacher feedback literacy: An instructional model for student feedback processes. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2021, 48, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bengtsson, M.; Carlson, E. Knowledge and skills needed to improve as preceptor: Development of a continuous professional development course—A qualitative study part I. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Houston, T.K.; Ferenchick, G.S.; Clark, J.M.; Bowen, J.L.; Branch, W.T.; Alguire, P.; Esham, R.H.; Clayton, C.P.; Kern, D.E. Faculty development needs. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lane, I.F.; Strand, E. Clinical veterinary education: Insights from faculty and strategies for professional development in clinical teaching. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2008, 35, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, Y.; Mann, K.V. Faculty Development: Principles and Practices. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2006, 33, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, S.T.; Couldry, R.; Phillips, H.; Buck, B. Preceptor development: Providing effective feedback. Hosp. Pharm. 2013, 48, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lane, I. Teaching is—Still—Job Number One. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2022, 260, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertis, M. The one-minute preceptor: A five-step tool to improve clinical teaching skills. J. Nurses Staff. Dev. 2007, 23, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallagher, P.; Tweed, M.; Hanna, S.; Winter, H.; Hoare, K. Developing the One-Minute Preceptor. Clin. Teach. 2012, 9, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neher, J.O.; Gordon, K.C.; Meyer, B.; Stevens, N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J. Am. Board. Fam. Pract. Am. Board. Fam. Pract. 1992, 5, 419–424. [Google Scholar]

| Benefits | References |

|---|---|

Enhances

| [2,4,5,6,18,39,47,48] |

Facilitates

| [2,4,5,6,17,19,51] |

Informs the learner on

| [5,6] |

Reinforces

| [2,5,6,33,39,47,48] |

| Category of Feedback | Type of Feedback | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Formal | Time required: 5–20 min. Usually provided around middle of the course/rotation, at least bi-monthly, or at the end of the activity. Provided following the guidelines for effective feedback. | [6,18,38] |

| Informal | Usually given during clinical encounters or the debriefing. More effective and influential. | [4,6] | |

| Duration of the session | In-depth (Major) | Time required: 10–30 min. Usually scheduled and provided weekly, around middle of the course/rotation, at least bi-monthly, and/or at the end of the activity. Should be in a private setting. Suitable for individual learners only. NOTE: The amount of exchanged information may overwhelm the learner. | [5,6,16,18,38] |

| Insignificant (Brief) 1 | Time required: <5 min. Usually unscheduled and discussion concentrates on everyday laboratory/clinical activities given in the context of the work. Should be given on-the-go or at least daily. Suitable for both individual learners and groups of learners | [4,5,6,16,38] | |

| Emotional aspect of the session | Constructive | Specific, Thoughtful, Actionable, Timely, Individualized, and Criterion-referenced (STATIC) and delivered in a nonevaluative, non-judgmental way. Assisting development of the learner; therefore, stimulating deep learning. | [5,6,31,32,48] |

| Destructive | General, subjective, and often judgmental assessment. Demotivating the learner; therefore, learner loses interest in deep learning. | [5,6,48] | |

| Quality of feedback | Effective | STATIC. | [13,16,27] |

| Ineffective | Delayed, generalized, non-actionable, non-specific, and vague. | [19,27] | |

| Mediocre | At least one of the elements of STATIC not provided effectively and/or vague. | [27] | |

| Sentiment of the session | Negative | Stating shortcomings/weaknesses and agreeing on strategies for improvements. Provision of negative feedback may be challenging. | [5,6,13,48] |

| Neutral | Generalized, not stating strengths or weaknesses. | [6] | |

| Positive | Reinforcing what has been done well/strengths. | [5,6,48] |

| Parameter | Appreciation | Coaching | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Informing the learner that their efforts are noticed | Helping to improve, learn, grow, or change, either to correct an existing problem or immerse in new challenges | Current performance, ranking against set of standards |

| Satisfies the need for | Building relationship | Correcting deficiencies, deep learning, facilitating development of learner–instructor relationship, learning guidance, mutual trust, reinforcing success, using failure as a catalyst for learning | Alignment of expectations between learner and instructor, clarification of consequences, ensuring attainment of competencies, guiding decision making, level of competencies, and setting expectations |

| Recommended phrasing | Nouns and verbs | Adjectives and adverbs | |

| Expression | Constructive and non-judgmental | Comparative and judgmental | |

| Timing | Continuous | Episodic | |

| Applicability to provision of effective feedback | None | High | Should be avoided although not completely excluded |

| Parameter | Five Microskills Model | Ask-Tell-Ask Model | Pendleton Rules | Sandwich Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application to clinical teaching | Wide 1 | Mid narrow 2 to wide | Mid narrow 2 to wide | Wide |

| Centered | Learner-centered | Learner-centered | Learner-centered | Instructor-centered |

| Description |

|

|

|

|

| Advantages |

|

|

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carr, A.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Use of Effective Feedback in Veterinary Clinical Teaching. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 928-946. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030066

Carr AN, Kirkwood RN, Petrovski KR. Use of Effective Feedback in Veterinary Clinical Teaching. Encyclopedia. 2023; 3(3):928-946. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarr, Amanda Nichole (Mandi), Roy Neville Kirkwood, and Kiro Risto Petrovski. 2023. "Use of Effective Feedback in Veterinary Clinical Teaching" Encyclopedia 3, no. 3: 928-946. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030066

APA StyleCarr, A. N., Kirkwood, R. N., & Petrovski, K. R. (2023). Use of Effective Feedback in Veterinary Clinical Teaching. Encyclopedia, 3(3), 928-946. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3030066