2. Characterizations

Regarding the definition of foreign direct investment in general, there are no major differences in the existing literature. The broad definition formulated by Czinkota et al. [

4] states that foreign direct investment is related to the expansion or establishment of operations of a company in a foreign (host) country. They add that the subject of FDI arises from the basic idea of the mobility of capital. Hill and Hult [

5] further suggest that FDI occurs when a company invests directly in facilities to produce or market a good or service in a host country. The capital investment is usually accompanied by further technological, material, information, financial or personnel flows. Shenkar and Luo [

6] add that the facilities in a host country in which a company invests must be effectively controlled.

In order to further explain the level of effective control, the following detailed definition provided by the OECD [

7] can be used. Foreign direct investment falls into the category of cross-border investments made by a resident in one economy (the direct investor) in order to create a lasting interest in a company domiciled abroad (the direct investment company), in an economy other than that of the direct investor. It is based on a strategic long-term relationship of the direct investor, the aim of which is to ensure a significant degree of its influence on the governance of the direct investment company. A “lasting interest” is demonstrated when the direct investor owns at least 10% of the voting rights of the direct investment company.

In this context, Gunter and Van der Hoeven [

8] also specify that foreign direct investment is made to acquire a lasting management interest (usually at least 10% of voting rights) in a company other than in the investor’s residence. Moreover, Gopinath [

9] states that foreign direct investment is effectively controlled from abroad, and may take the form of a new enterprise (greenfield) or acquisition of a controlling interest in an existing enterprise (merger or acquisition). It represents a high level of investor involvement in the country and is usually long-term. Hence, a key feature of foreign direct investment is that it establishes either effective control over foreign business decision-making, or at least it has a significant influence thereon.

From an organizational point of view, according to the OECD [

7], direct investment companies can be either associates, in which between 10% and 50% of the voting rights are held; or subsidiaries, in which over 50% of the voting rights are held; or they may take the form of branches that are effectively 100% owned by their respective parents. The relationship between a direct investor and a direct investment company may be complex and may have little or no relationship to governance structures.

Special attention should be paid also to the term “direct investor”. Although foreign direct investors are traditionally considered to be business companies, especially multinationals, in recent decades, private equity investors, venture capitalists and sovereign wealth funds have also been associated with this phenomenon. In this context, Caselli and Negri [

10] highlight the fact that these entities are creators of better businesses, which can in turn attract other private equity companies ready to drive target companies to the next development level, or other strategic investors seeking new growth opportunities.

From a directional point of view, it is important to distinguish inward and outward FDI. Since the key focus of the present paper is inward FDI, it can be defined as an investment made by a non-resident direct investor in a company residing in the host economy, which is referred to as the reporting economy. Inward FDI provides a useful indicator of the attractiveness of economies as target investment locations, since it reflects the benefits arising from a host country’s locational advantages to foreign direct investors.

This aspect is highlighted in Dunning’s eclectic paradigm [

11], which explains the determination of FDI by three sets of advantages. Besides an internalization advantage and a specific ownership advantage, a target investment destination should also offer to an investor a specific location advantage. It may take the form of an economic advantage (low production cost, market size, developed infrastructure, economic stability, geographic location, etc.), a political advantage (investment promotion policy, free trade, political stability) or a social advantage (language and cultural proximity).

2.1. Typology of Foreign Direct Investment

Cross-border movement of capital can be made in a variety of ways and can cover distinct activities with different strategic logic underlying the FDI. Hence, it is important to deal with types of FDI from at least the three following points of view [

6]:

First, entry mode typology refers to the manner in which a company enters a foreign market through FDI. It usually includes [

5]:

The literature makes a special distinction between mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and greenfield investments, because they are likely to impact the host economy in different ways. In this regard, Davies et al. [

12] highlight the following differences between the two: M&As involve the transfer of ownership for reasons of integration or arbitration, while greenfield investments rely on companies’ own capacities and capabilities, which are linked to the attributes of the country of origin. Moreover, there are also significant differences with regard to cost. As indicated by Czinkota et al. [

4], while greenfield investment is the most expensive foreign investment alternative, especially in terms of time and effort, acquisition of an existing company may be associated with lower initial costs, but further customizing and adjustment costs may occur later.

Second, FDI is commonly categorized according to its link to the type of original (core) business operation (products and services) of the investing company. A horizontal FDI occurs when an investor establishes the same type of business operation abroad as in the home country, which results in the geographical diversification of the same product line. A vertical FDI occurs when related business activities are established or acquired abroad. The relation of business activities can take an upstream form (activities connected with production of inputs) or a downstream form (activities connected with finalization or commercialization of the outputs originally produced by the foreign investor). A conglomerate FDI is made by an investor in a business abroad that is unrelated to the existing business in its home country. Since this type of investment involves entering a new sector in which the investor usually has no previous experience, it is often made through a joint venture with a foreign company already operating in the sector.

Third, based on the strategic logic behind the FDI connected with investment motivation, FDI, according to Dunning [

13], can take the form of:

Resource-seeking FDI, when a company aims to access raw materials, labor and/or physical infrastructure resources in a host country at a lower cost than at home.

Market-seeking FDI, when a company geographically diversifies its activities to access host country markets in order to secure market share and sales growth in the target foreign markets.

Efficiency-seeking FDI, when a company seeks to rationalize the structure of already established resources or market-oriented investments in order to benefit from the common governance of geographically spread activities.

Strategic assets-seeking FDI, when a company aims to access key assets of foreign companies, such as capabilities in research and development, innovation and advanced technology, in order to promote its long-term strategic objectives.

2.2. Measurement of Inward Foreign Direct Investment

In accordance with the recommendations of the OECD [

7], the presentation of FDI data should be designed to provide information reflecting the direction of the impact underlying the direct investment. When the investment is inward, the influence it has caused comes from abroad and results in the establishment of a direct investment company in a host economy.

Direct investment statistics usually cover all cross-border transactions and positions between companies which form part of the same group. According to the OECD [

7], FDI statistics are usually based on following principles:

They take into account direct as well as reverse investments (i.e., the reverse investments of the host country’s foreign investment companies are recorded as negative inward investments);

The direction of the investment depends on whether the ultimate controlling parent of the resident fellow company is a resident or a non-resident of the host economy;

The volume of inward foreign direct investment over a given time represents the flow, while the cumulative sum of inflow is inward stock, which represents the total accumulated volume of FDI in the host economy at a particular time;

At the same time, direct investment statistics are presented with a geographical and industry breakdown—for inward FDI the allocation by partner country uses the debtor/creditor principle;

Indicative data for both geographical and industrial analysis should be derived from basic information on FDI assets and liabilities.

According to the recommendation of the OECD [

7], inward FDI statistics consist of three basic statistical accounts:

Direct inward FDI positions that provide information on the total stock of investment received from abroad, broken down by instrument (equity, debt), usually reported at the end of the calendar year.

Direct inward investment income flows show information on the earnings of the direct investment company that arise from equity (distributed as well as undistributed earnings) and from debt (i.e., interest from inter-company loans, trade credits and other forms of debt).

Direct inward investment financial transactions reflect the net inward investments with assets and liabilities presented separately by instrument (equity, debt) in any given reference period, usually a year. They consist mainly of three types of transactions: acquisition of equity capital, reinvestment of earnings that are not distributed as dividends, and inter-company debt (payables and receivables, loans, debt securities).

If there is a difference between closing and opening FDI positions in a particular reporting period that cannot be explained by financial transactions, it is referred to as “other changes” that arise from movements in foreign currency, price volatility, etc.

3. Effects of Inward Foreign Direct Investment

From a host country perspective, several often contradictory effects are connected with inward FDI. The literature (for instance, [

4,

5,

14]) most often draws attention to the following effects.

FDI is particularly beneficial for countries with restricted domestic resources to raise funds in international capital markets. Besides capital transfers, FDI is usually connected with a supply of other sources such as technology or managerial skills. Local companies can thus engage in joint projects with foreign investors that would be unattainable for them alone. New operation facilities developed through these projects may then substantially reduce the need to import produced items and at the same time foster exporting. All these effects should subsequently positively affect the balance of payments of the host country as well as its economic growth [

15,

16]. For example, an empirical study carried out by Pegkas [

17] revealed a positive long-term cointegrating relationship between the stock of foreign direct investment and economic growth in Euro-area countries.

The creation of employment opportunities, not only directly within the foreign investment company, but also indirectly in other networking local companies, is probably the most positive effect of inward FDI. Several studies (for example, [

18]) have shown that inward FDI reduces unemployment, especially in developing and transition countries. The creation of new jobs is often connected with a need to train the new workforce, usually resulting in the development of advanced skills and higher productivity.

In addition, knowledge transfers and subsequent superior innovation performance of the host country were found by many studies [

19,

20,

21] to be other positive effects of inward FDI. These findings are most commonly explained by the direct increase of innovation output through activities of more innovative companies of foreign or mixed ownership, as well as by indirect spillovers that affect domestic companies through the transfer of supply chain technologies. Due to superior technologies often connected with higher productivity, foreign-owned companies can pay employees higher wages than their domestic counterparts (proven in studies by Fatima, Khan [

22]; Paweenawat [

23]; Peric, Filipovic [

24]) and hence contribute to a higher wage levels in the host country and potentially also to a higher standard of living.

Better functioning of public institutions, including reduction of corruption under the influence of foreign investors, forms one of the other generally perceived positives of FDI inflows, especially in developed countries. As pointed out by Pinto and Zhu [

25], foreign investors entering competitive markets in developed countries have reduced opportunities for rent creation, which in turn mitigates corrupt behavior.

On the other hand, foreign direct investment often flows only into those sectors that offer opportunities to exploit the foreign investor’s internalization advantage and thus enhances concentration of investors only in particular sectors. There are some studies (for instance, [

26]) that point out that sectoral concentration of inward FDI in host economies usually leads to a higher dependence of the host economy on a few sectors or even companies. As a result, there is an asymmetry in inward FDI location and concentration being in the hands of a relatively small number of companies.

Moreover, when a foreign investment company is unable to find appropriate local suppliers, it has a tendency to maintain relationships with its domestic or other foreign suppliers. Ultimately, inward FDI can have a negative effect on the balance of payments, due to increased imports to the host country, which has been found especially in developing countries [

27]. Further negative effects directly connected with inward FDI lie in repatriation of profits generated in the host country to the parent company, which becomes a barrier to the economic development of the host region [

28].

Technological progress brought by inward FDI to host economies usually goes hand in hand with the tendency for brain drain, as researchers from host countries are attracted to centralized research facilities located abroad. Hence, the deleterious consequences of inward FDI on the innovativeness of local companies can also be obvious [

29,

30].

With regard to generally higher wages paid by foreign-owned companies, there is empirical evidence (for example, [

31,

32]) that inward FDI exacerbates wage income inequality. As a consequence, social pressures, as well as slowing economic growth, can occur.

Another group of problems associated with inward FDI are ecological consequences. Several studies have shown that FDI sometimes degrades the environment (for example, [

33,

34]), which is supported by the pollution-haven hypothesis. This theory suggests that insufficient environmental regulation can attract FDI seeking to circumvent the environmental costs imposed on them in the home country by moving the polluting production stages to other (host) countries.

The political consequences of inward FDI are also not negligible. Intense policy competition between countries attracting inward FDI can lead to the so-called race to the bottom, which means that the effects of foreign direct investment will not ultimately cover the public costs connected with providing investment incentives [

35]. Moreover, the governments of smaller countries may eventually become hostages to major foreign investors. In addition, the other effects expected from investment incentives may also not be met (for example, [

36]), and many countries have reduced or even abolished investment incentives as a result of these circumstances [

37].

The key positive and negative effects of inward FDI from the host economy perspective are briefly summarized in the following

Table 1.

It is worth noting that FDI contributes to the economic development of host countries only to the extent that the benefits brought by this investment effectively eliminate the negative externalities generated by foreign investors. Thus, when attracting inward FDI, a rational approach that is shaped by a consideration of the positive effects along with the costs associated with inward FDI should be applied.

4. Evaluation of Inward Foreign Direct Investment

Regular evaluation of inward FDI development and its trends forms an integral part of macro-economic financial analysis. In order to get a picture of the stock and flows of inward foreign direct investment in the world, besides an overview of the development of the volume of these indicators over time, several other specific indicators can be used.

The degree of concentration of FDI reflects the overall level of geographic concentration of inward FDI. For this purpose, a concentration ratio (used, for instance, by Shenkar, Luo [

6]) can be calculated as a portion of inward FDI stock held by the top ten investment-receiving countries. A decrease in this ratio implies that investments are more geographically diversified.

For cross-country comparisons, it is suggested to use relative measures, such as inward FDI flow expressed as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This indicator provides basic information on the relative attractiveness of the host economy and its industries for new investment as well as the importance of the earnings of direct investment companies. At the same time, the ratio of inward FDI to GDP indicates the extent of a foreign presence or foreign ownership in the host economy [

7].

The relative success of a particular country in attracting FDI can be more precisely measured by the inward FDI performance index introduced by UNCTAD [

38]. The index relates inward FDI flow to the economic size of the particular country, measured by GDP. More specifically, it is calculated as a ratio of a country’s share in global inward FDI to its share in global GDP. Values above one show that the country receives a higher portion of FDI compared to its relative economic size, while values below one show that the country receives a lower portion of FDI than its relative economic size. This measure has already been used in several studies for the purpose evaluating the advantages connected with FDI flows (for example, [

39,

40]).

Since companies are considered to be key bearers of FDI, Gattai and Sali [

41] recommend analyzing the evolution of FDI through a firm-level perspective, namely to take into account the so-called “extensive” and “intensive” margins of FDI. The first concerns the number of companies involved in FDI, while the second concerns the depth of FDI involvement. The results of their study conducted in the European Union suggest that a relatively large number of companies with relatively low involvement are responsible for the outstanding performance of the EU as a target destination for inward FDI.

5. Development of Inward Foreign Direct Investment in the World

This section provides a basic worldwide overview of inward FDI flows and stocks in recent decades. For comparison purposes, inward FDI under the conditions of developed, developing and transition countries are distinguished.

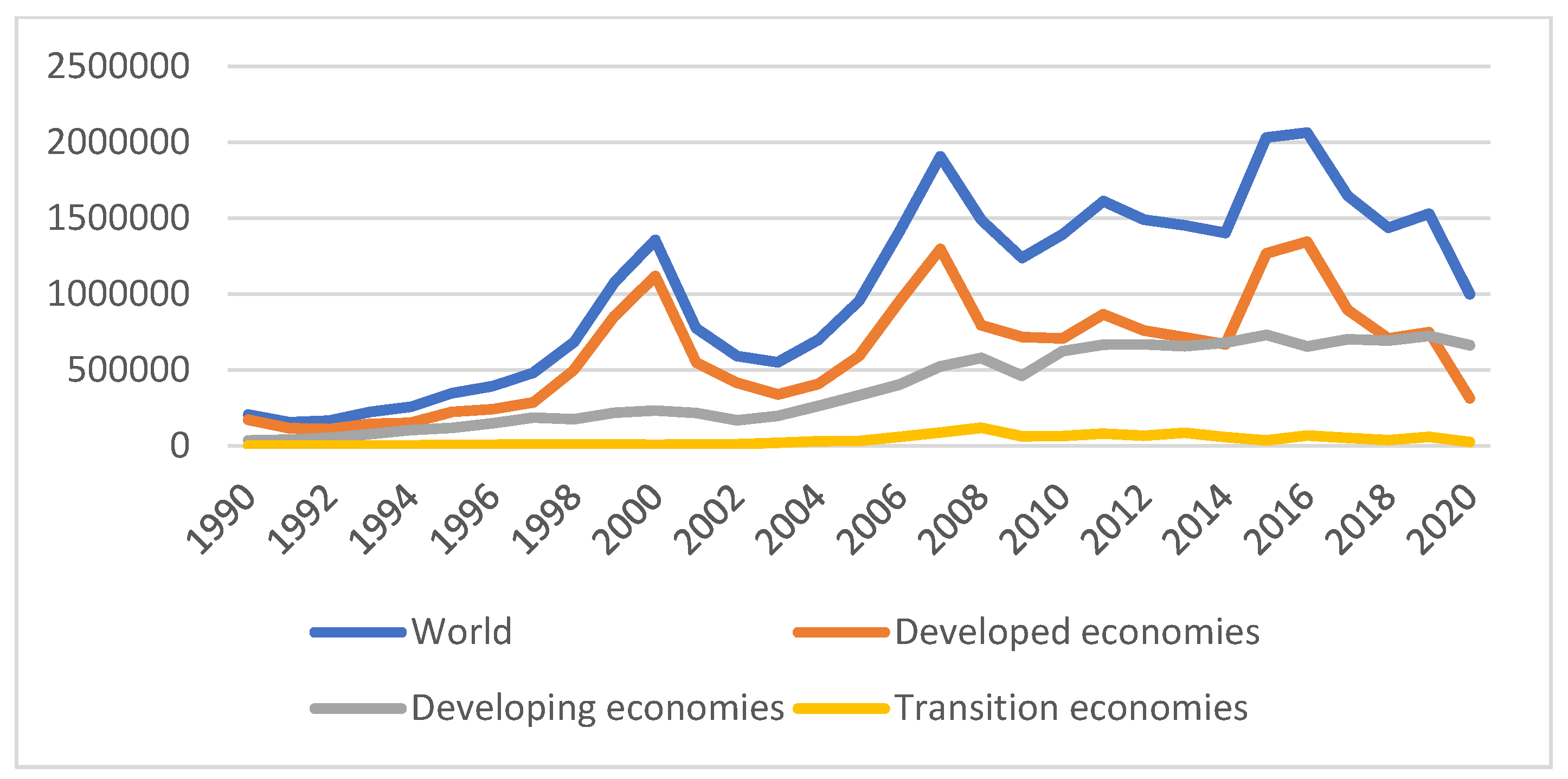

Figure 1 reports the volume of inward FDI flows in the period of 1990–2020.

In most of the observed period, the drivers of the inflow of foreign direct investment in the world were developed economies. They have been considered as attractive targets for inward FDI due to their favorable political environment, dynamic economies, stable institutions and wealthy domestic markets [

5]. However, the trend changed in 2014 when, for the first time, FDI inflows to developing countries exceeded FDI inflows to developed countries, possibly also due to natural resource endowment as one of the significant factors positively determining FDI inflows [

43]. Much of the increase has been driven by China, which, as recipient of FDI, attracted almost USD 150 billion of FDI, accounting for more than 20% of the FDI inflow to developing economies. There was a slight increase in FDI flows to transition economies, which gradually have become attractive investment locations [

44].

The last monitored year, 2020, brought, however, significant changes in these trends. There was an obvious year-on-year decline in the volume of inward foreign direct investment that can be explained in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. As documented by Ho and Gan [

45], there was a decrease in FDI net inflows worldwide (obvious also from

Figure 1) caused by pandemic uncertainty, which influenced transnational companies’ behavior, especially in emerging economies and the Asia and Pacific regions.

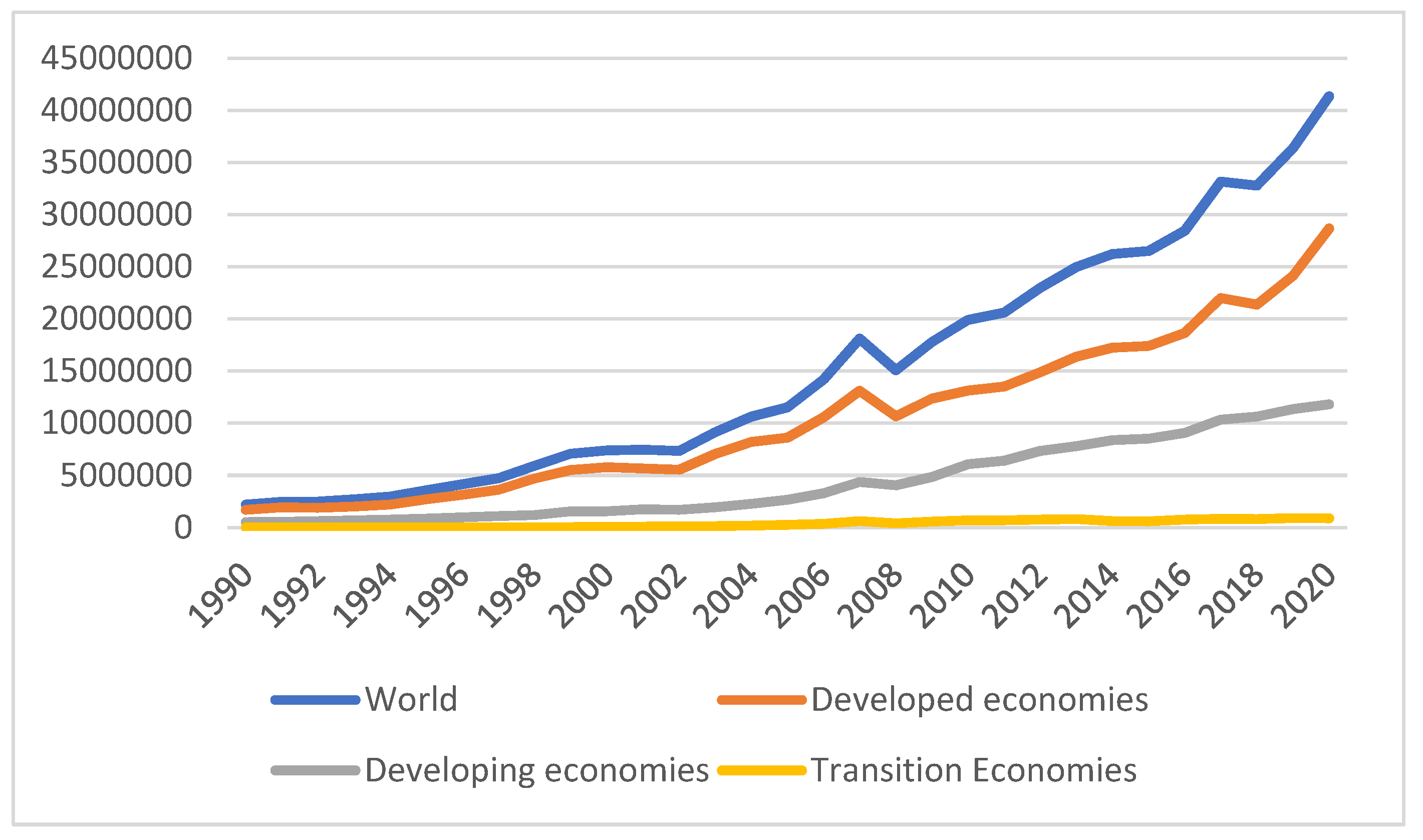

The accumulated stock of foreign direct investment by groups of countries can be seen in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows gradual increase in the inward FDI stock accumulated by the particular country groups during the last thirty years. During this period, the total inward FDI stock worldwide increased more than eighteen times. The biggest leap in this direction was recorded by the transition economies, followed by the developing and developed economies. The popularity of inward FDI in comparison to world trade can be explained by the fact that FDI circumvents trade barriers, and is driven by economic and political changes, as well as by globalization [

5].

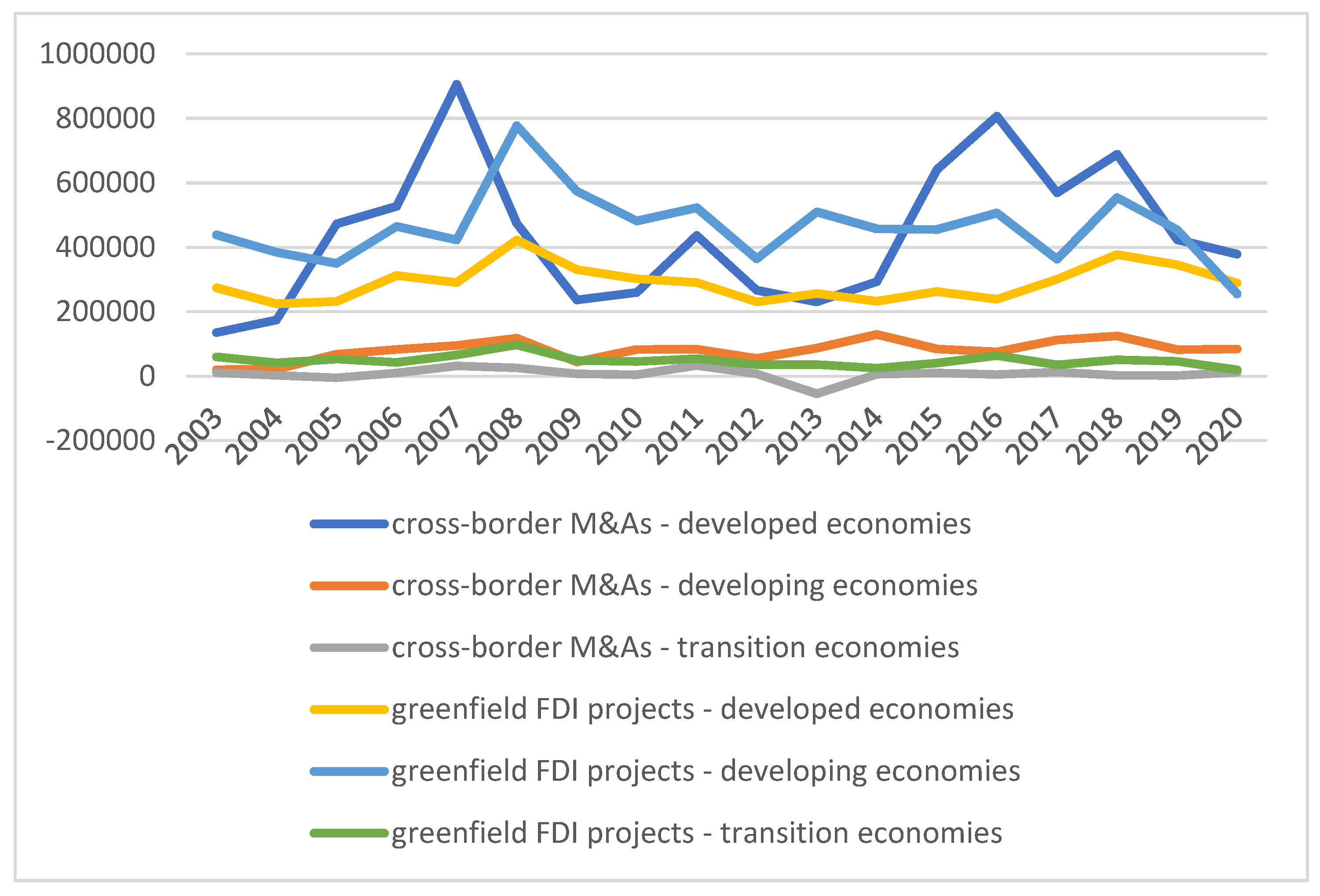

Furthermore, it is also important to identify inward FDI by types, since mergers and acquisitions or greenfield investments are likely to have different impacts on the host economy.

Figure 3 reports the values of net cross-border M&As by country groups of sellers as well as the values of announced greenfield FDI projects by the target group of countries.

Figure 3 shows that there is a difference in preferred types of inward FDI across the groups of countries. Greenfield projects are most preferred in developing countries; they reached a total value of USD 8300 billion in the observed period of 2003–2020. On the other hand, the majority of inward FDI in developed countries occurred as cross-border M&As; the total value was USD 7900 billion. The lower share of mergers and acquisitions performed in developing countries simply reflects the fact that there are fewer target companies to acquire than in the developed part of the world [

5].

With respect to the effects of these types of inward FDI on overall economic development, it is worth mentioning the study by Harms and Méon [

46], conducted on 127 industrialized, emerging and developing countries. According to the authors, greenfield FDI had a more significant impact on economic growth than M&As; this is because M&As partly represent a rent attributable to previous owners and do not necessarily contribute to the expansion of the host country’s capital stock.

Table 2 provides a list of the ten countries that reported the highest volume of inward FDI stock in 2020. In addition, the portion of inward FDI stock on total worldwide stock, inward FDI flows expressed as a percentage of GDP and inward FDI performance index are shown.

The table shows selected inward FDI indicators of the 10 countries in the world holding the highest stock of inward FDI in 2020. It is obvious that not only large countries, but also relatively small ones such as Singapore or Switzerland, are attractive investment locations. The concentration ratio of the inward FDI stock for these top 10 countries reached a value of 64.33% in 2020, which indicates that the majority of inward FDI is still focused on these top 10 investment-receiving countries. A look at earlier data provided by Shenkar and Luo [

6] shows that there has been a slight decrease in the concentration ratio for inward FDI stock. While in 1985 it was 70.4%, in 2000 it decreased to 67.7%, and 20 years later, a further slight decrease is visible. It appears that investments tend to be more geographically diversified, which at the same time, indicate a tendency from globalization towards regionalization of FDI. Arregle et al. [

48] also pointed out that regional integration and aggregation of foreign direct investment is a typical feature of the internationalization decision-making in transnational companies.

On the other hand, a relative comparison of countries using FDI to GDP provides another picture. The most successful economies in terms of attracting FDI in 2020 were Hong Kong, Singapore and Ireland, followed by Canada. Their relatively high portion of inward FDI flows to GDP is reflected also in the inward FDI performance index with values above one. These countries attracted a higher portion of FDI compared to their relative economic size. The rest of the countries attracted relatively less inward FDI than might be expected given their economic size. This is particularly true for the Netherlands and Switzerland, which reported negative volumes of inward FDI flows in 2020.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

This study was aimed at providing an explanation of the basic notion of foreign direct investment; in this regard, inward FDI usually reflects the localization advantage of the host economy. The presentation of the effects associated with this type of investment points to the controversies that arise in this regard in host countries. These facts are also reflected in the findings of the empirical literature. It should be noted that FDI generates positive impacts on the economic development of host countries only if the benefits of this investment outweigh the negative externalities created by foreign investors.

The evaluation of inward FDI and its worldwide overview showed a significant increase in inward FDI stock in past decades, accompanied by the dominance of developed countries in this regard. However, there is an obvious tendency of the developing, and, to some extent, transition countries in catching up with their more developed counterparts in attracting inward FDI. At the same time, it seems that pandemic uncertainty negatively influenced inward FDI flows, and the recovery process will depend on strengthening the investment environment.

Future research aimed at a detailed comparison of localization advantages of developed and developing countries and their changes over a particular time could shed more light on the issue and outline future destinations of inward FDI. For instance, with regard to the countries of the European Union, the applicability of investment development path theory forms interesting research challenges. Moreover, deeper investigation of the effects associated with inward FDI requires a more region-specific approach. There are also clear differences in the types of inward FDI carried out in different countries. While developed countries and their companies are preferable targets of mergers and acquisitions, in the case of developing countries, greenfield investment projects most frequently occur. Therefore, the combined effect of differences in localization advantages together with different types of inward FDI can lead to the contradictory effects associated with inward FDI found in the empirical literature. These considerations are worth further investigation.