Changes in Food Service Operations in a Brazilian Tourist Area: A Longitudinal Approach to the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. COVID-19 Pandemic

2.2. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Brazilian Food Services

3. Materials and Methods

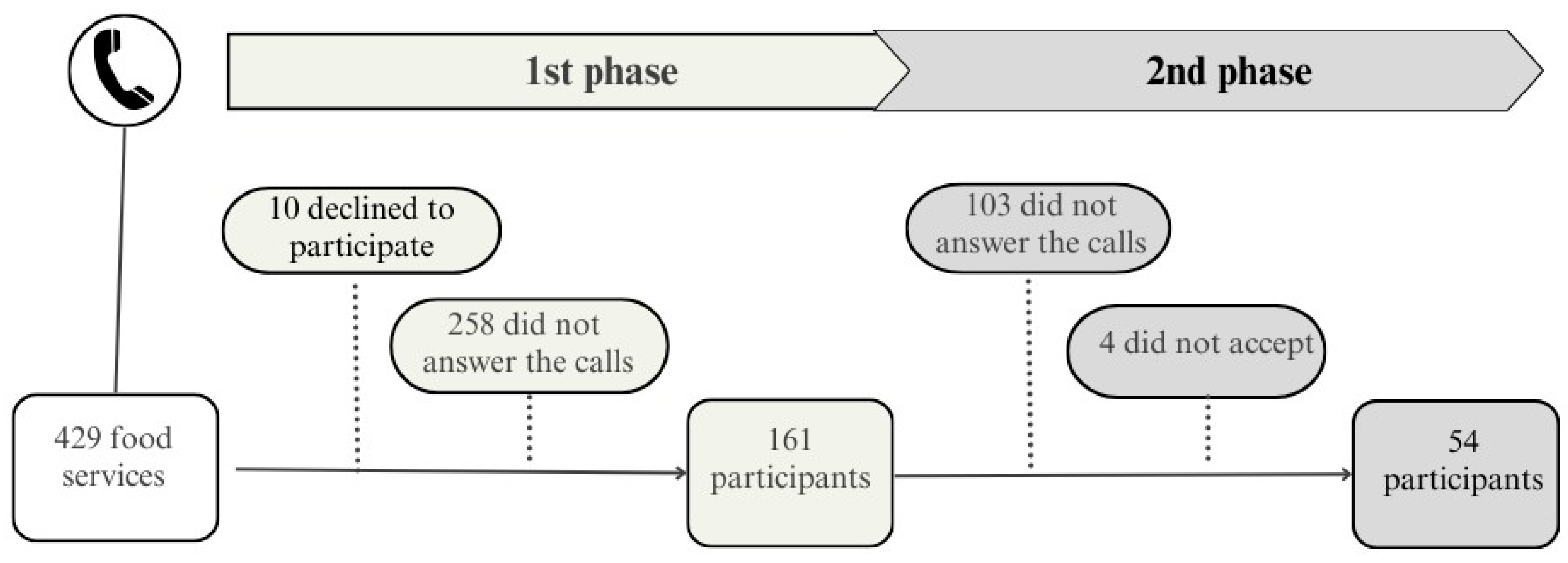

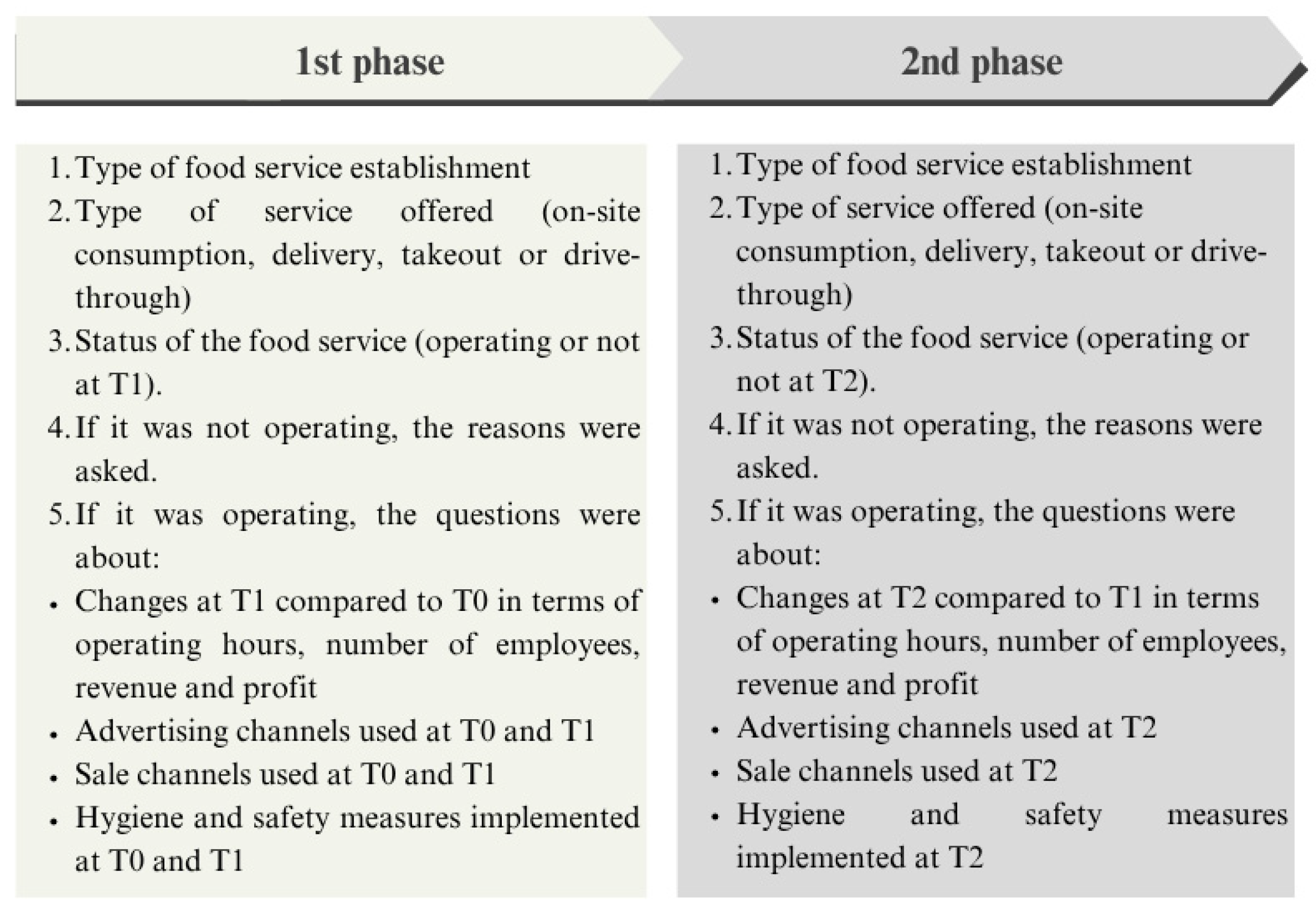

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Data Collection Instrument

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dias, G.N.; Aires, I.O.; de Sousa, F.R.; Araújo, M.C.; Moura, A.C.C.; Lima, S.M.T.; Moura Menêzes, J.V.; Da Silva, M.S.; Revoredo, C.M.S. A importância da ergonomia em unidades de alimentação e nutrição: Uma revisão integrativa. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2020, 38, e1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (ABRASEL). Food Service 2024: Fique por Dentro das Principais Tendências Para o Setor. 2024. Available online: https://pe.abrasel.com.br/noticias/noticias/food-service-2024-fique-por-dentro-das-principais-tendencias-para-o-setor/#:~:text=Tend%C3%AAncias%20do%20food%20service%20para%202024&text=As%20dark%20kitchens%20e%20o,de%20acordo%20com%20a%20Kantar (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): How is it Transmitted? 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted. (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto no 10.282, de 20 de Março de 2020; Regulamenta a Lei no 13.979, de 6 de Fevereiro de 2020, Para Definir os Serviços Públicos e as Atividades Essenciais; Planalto: Brasilia, Brasil, 2020.

- Malta, D.C.; Gomes, C.S.; da Silva, A.G.; Cardoso, L.S.d.M.; Barros, M.B.d.A.; Lima, M.G.; de Souza Junior, P.R.B.; Szwarcwald, C.L. Use of health services and adherence to social distancing by adults with noncommunicable diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic, Brazil, 2020. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2021, 26, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.C.; de Silva, C.L.; Liboredo, J.C. Food service safety and hygiene factors: A longitudinal study on the Brazilian consumer perception. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1416554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.H.D.; Vu, D.C. Food delivery service during social distancing: Proactively preventing or potentially spreading COVID-19? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, e9–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Bilal, M.; Moiz, A.; Zubair, S.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Food safety and COVID-19: Precautionary measures to limit the spread of Coronavirus at food service and retail sector. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 14, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota Técnica no 18/2020/SEI/GIALI/GGFIS/DIRE4/ANVISA. Covid-19 e as Boas Práticas de Fabricação e Manipulação de Alimentos 2020. Available online: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/219201/4340788/NT+18.2020+-+Boas+Práticas+e+Covid+19/78300ec1-ab80-47fc-ae0a-4d929306e38b (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota Técnica no 48/2020/SEI/GIALI/GGFIS/DIRE4/ANVISA. Documento Orientativo para Produção Segura de Alimentos Durante a Pandemia de Covid-19 2020. Available online: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/219201/4340788/NOTA_TECNICA_N__48___Boas_Praticas_e_Covid_19__Revisao_final.pdf/ba26fbe0-a79c-45d7-b8bd-fbd2bfdb2437 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz). Pandemia de Covid Encolhe e 2023 foi o ano com Menos Mortes. 2022. Available online: https://fiocruz.br/noticia/2022/01/brasil-celebra-um-ano-da-vacina-contra-covid-19 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota técnica no 49/2020/SEI/GIALI/GGFIS/DIRE4/ANVISA 2020. Available online: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/219201/4340788/NOTA_TECNICA_N__49.2020.GIALI__orientacoes_atendimento_ao_cliente.pdf/e3cb8332-e236-482f-b446-cb2a39dc4589. (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota Técnica No 47/2020/SEI/GIALI/GGFIS/DIRE4/ANVISA. Uso de Luvas e Máscaras em Estabelecimentos da Área de Alimentos no Contexto do Enfrentamento ao COVID-19. 2020. Available online: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/219201/4340788/NOTA_TECNICA_N__47.2020.SEI.GIALI_0_uso_de_EPIs.pdf/41979d87-50b8-4191-9ca8-aa416d7fdf6e (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Moreira, M.d.F.; Meirelles, L.C.; Cunha, L.A.M. Covid-19 no ambiente de trabalho e suas consequências à saúde dos trabalhadores. Saúde Em Debate 2021, 45, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Silva, R.d.C.; Pereira, M.; Campello, T.; Aragão, É.; Guimarães, J.M.d.M.; Ferreira, A.J.F.; Barreto, M.L.; Santos, S.M.C. Covid-19 pandemic implications for food and nutrition security in Brazil. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 3421–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W.R.S.d.; Cechin, A. Efeitos da Pandemia da Covid-19 nos Preços dos Alimentos no Brasil. Rev. Catarin. Econ. 2021, 5, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (ABRASEL). Crise Leva ao Fechamento de 40% dos Restaurantes de Comida a Quilo. 2021. Available online: https://abrasel.com.br/noticias/noticias/crise-leva-ao-fechamento-de-40-dos-restaurantes-de-comida-a-quilo/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). PAHO/WHO Belize Response to COVID-19: January to August 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/PAHO%20Belize%20Covid-19%20Response%20Report.pdf. (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- WHO. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Campos, M.R.; Schramm, J.M.A.; Emmerick, I.C.M.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Avelar, F.G.d.; Pimentel, T.G. Burden of disease from COVID-19 and its acute and chronic complications: Reflections on measurement (DALYs) and prospects for the Brazilian Unified National Health System. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00148920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhand, R.; Li, J. Coughs and sneezes: Their role in transmission of respiratory viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2. American J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Dashboard 2025. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Wise, J. Covid-19: WHO declares end of global health emergency. BMJ 2023, 381, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: A mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, R.; Roknuzzaman, A.S.M.; Hossain, M.J.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Islam, M.R. The WHO declares COVID-19 is no longer a public health emergency of international concern: Benefits, challenges, and necessary precautions to come back to normal life. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 2851–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; MacGregor, H.; Scoones, I.; Wilkinson, A. Post-pandemic transformations: How and why COVID-19 requires us to rethink development. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanke, A.A.; Thenge, R.R.; Adhao, V.S. COVID-19: A pandemic declare by world health organization. IP Int. J. Compr. Adv. Pharmacol. 2020, 5, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, L.M.; Zoratto, G.; Calegaro, V.C.; Ramos-Lima, L.F.; Negretto, B.L.; Hauck, S.; Freitas, L.H. COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing: Economic, psychological, family, and technological effects. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 43, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahagamage, Y.; Marasinghe, K. The socio-economic effects of COVID-19. Saúde Soc. 2023, 32, e200961en. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Brazil: Food Service Industry Growth 2010–2019. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/812710/foodservice-market-cagr-brazil/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Shah, A. Revisiting food delivery apps during COVID-19 pandemic? Investigating the role of emotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, E.; Cheng, Y. Customers’ risk perception and dine-out motivation during a pandemic: Insight for the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffani, F. Food Service—Hotel Restaurant Institutional. 2021. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/brazil-food-service-hotel-restaurant-institutional-3 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (ABRASEL). Cerca de 300 mil Restaurantes Fecharam as Portas no Brasil em 2020. 2021. Available online: https://abrasel.com.br/noticias/noticias/cerca-de-300-mil-restaurantes-fecharam-as-portas-no-brasil-em-2020/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Bacao, F. What factors determining customer continuingly using food delivery apps during 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic period? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e restaurantes (ABRASEL). Delivery chega a 89% dos Restaurantes Brasileiros com a Pandemia da Covid. 2021. Available online: https://abrasel.com.br/noticias/noticias/delivery-chega-a-89-dos-restaurantes-brasileiros-com-a-pandemia-da-covid/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Zanetta, L.D.; Hakim, M.P.; Gastaldi, G.B.; Seabra, L.M.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Nascimento, L.G.P.; Medeiros, C.O.; Cunha, D.T.d. The use of food delivery apps during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: The role of solidarity, perceived risk, and regional aspects. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Nikolic, A.; Uzunovic, M.; Marijke, A.; Liu, A.; Han, J.; Brncic, M.; Knezevic, N.; Papademas, P.; Lemoniati, K.; et al. Covid-19 pandemic effects on food safety—Multi-country survey study. Food Control 2021, 122, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Nour, M.O.; Osaili, T.M.; Alkhalidy, H.; Al-Holy, M.; Ayyash, M.; Holley, R.A. The effect of the knowledge, attitude, and behavior of workers regarding COVID-19 precautionary measures on food safety at foodservice establishments in Jordan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas (SEBRAE); Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (ABRASEL). Situação e Perspectiva dos Segmentos de Alimentação fora do lar. 2ª Edição. 2020. Available online: https://redeabrasel.abrasel.com.br/upload/files/2020/08/EGNMNa49RLwks9YwvClb_31_58ec68afc5677fa8d059774cc4942bfd_file.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Silveira, J.; Ribeiro, C.S.G.; Gimenes, L.C.S. Adaptations in the management of food and nutrition units during the Covid-19 pandemic. Research. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e40101320758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matijević, J.; Zielinski, S.; Ahn, Y.-J. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 Recovery Strategies in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messabia, N.; Fomi, P.-R.; Kooli, C. Managing restaurants during the COVID-19 crisis: Innovating to survive and prosper. J. Innov. Knowlodge 2022, 7, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. Estudo Mostra o Impacto da Pandemia em Hotéis e Restaurantes de Regiões Turísticas. 2021. Available online: https://forbes.com.br/forbeslife/2021/01/estudo-mostra-o-impacto-da-pandemia-em-hoteis-e-restaurantes-de-regioes-turisticas/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Amaral, M.M.; Flores, L.C.S. Visitors’ gastronomy experiences in a winescape. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Em Tur. 2025, 19, e-3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvén, A.; Beery, T.; Kristofers, H.; Johansson, M.; Carlbäck, M.; Wendin, K. Outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism and food: Experiences and adaptations in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 pandemic—A review. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 4, 1529233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, R.; Pozzi, A. Gastronomy tourism and covid-19: Technologies for overcoming current and future restrictions. In Tourism Facing a Pandemic: From Crisis to Recovery; Burini, F., Ed.; University of Bergamo: Bergamo, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-88-97253-04-4. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L. Virtual Culinary Tourism in the Time of COVID 19. Vis. Leis. Bus. 2022, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowska-Tryzno, A.; Pawlikowska-Piechotka, A. Gastronomy tourism and the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Sport i Turystyka. Srod. Czas. Nauk. 2022, 5, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monitor Mercantil. Responsáveis por 3,6% do PIB, Bares e Restaurantes Movimentam R$ 416 bi. 2024. Available online: https://monitormercantil.com.br/responsaveis-por-36-do-pib-bares-e-restaurantes-movimentam-r-416-bi/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (ABRASEL). Custos Elevados e Dívidas Comprometem Lucros de Bares e Restaurantes em Outubro. 2024. Available online: https://www.abrasel.com.br/noticias/noticias/custos-elevados-dividas-outubro/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Hakim, M.P.; Libera, V.M.D.; Zanetta, L.D. ’A.; Stedefeldt, E.; Zanin, L.M.; Soon-Sinclair, J.M.; Zdzisława, M.; Cunha, D.T. Exploring dark kitchens in Brazilian urban centres: A study of delivery-only restaurants with food delivery app. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 112969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Nacional de Restaurantes (ANR). Projeções Para o Crescimento do Foodservice em 2025 Indicam Expansão de até 6.25%. 2024. Available online: https://www.anrbrasil.org.br/projecoes-para-o-crescimento-do-foodservice-em-2025-indicam-expansao-de-ate-625/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Gaulinon, A.N.R.; Associação Nacional de Restaurantes, ABIA. Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Alimentos. Alimentação hoje: A Visão dos Operadores de Estabelecimentos do Foodservice—2ª Edição. 2024. Available online: https://www.galunion.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Visao-dos-Operadores-de-Foodservice_ANR_GALUNION_ABIA_2a-edicao-2024.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Penna, J.A.; Região dos Inconfidentes: Desafios e Potencialidades Pós-Pandemia. Agência Primaz 2020. Available online: https://www.agenciaprimaz.com.br/2020/05/31/regiao-dos-Inconfidentes-desafios-e-potencialidades-pos-pandemia/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Associação Nacional de Restaurantes (ANR). Gaulinon. Alimentação na Pandemia: A Visão dos Operadores de Foodservice—Nov-Dez-2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.galunion.com.br/links-galunion/materiais/pesquisa_alimentacao_na_pandemia_galunion_anr_operadores3.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Rizou, M.; Galanakis, I.M.; Aldawoud, T.M.S.; Galanakis, C.M. Safety of foods, food supply chain and environment within the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 102, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 and Food Safety: Guidance for Good Businesses 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/covid-19-and-food-safety-guidance-for-food-businesses (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2017–2018: Avaliação Nutricional da Disponibilidade Domiciliar de Alimentos no Brasil 2020. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=2101704 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2002–2003. Primeiros Resultados; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008–2009: Análise do Consumo Alimentar Pessoal no Brasil.; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (Abrasel). Público Volta e Restaurantes Faturam Mais. 2022. Available online: https://www.abrasel.com.br/noticias/noticias/publico-volta-e-restaurantes-faturam-mais/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Liboredo, J.C.; Amaral, C.A.A.; Caldeira de Carvalho, N.C. Using of food service: Changes in a Brazilian sample during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 54, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liboredo, J.C.; Amaral, C.A.A.; Carvalho, N.C. Food delivery before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Nutr. Food Sci. 2023, 53, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T.M.d.; Lua, I. O trabalho mudou-se para casa: Trabalho remoto no contexto da pandemia de COVID-19. Rev. Bras. Saúde Ocup. 2021, 46, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, P.d.S.; Freitas, A.M.C.; Cardoso, M.d.C.B.; Silva, J.S.d.; Reis, L.F.; Muniz, C.F.D.; Araújo, T.M.d. Trabalho remoto docente e saúde: Repercussões das novas exigências em razão da pandemia da Covid-19. Trab. Educ. Saúde 2021, 19, e00325157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, M.V.; Oliveira, T.C.; José, J.F.B.d.S. Food service as public health space: Health risks and challenges brought by the covid-19 pandemic. Interface Commun. Health Educ. 2021, 25, e200654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.C.; Osaili, T.M.; Mohamad, M.N.; Marzouqi, A.; Al Jarrar, A.H.; Jamous, D.O.A.; Magriplis, E.; Ali, H.I.; Sabbah, H.; Al Hasan, H.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle during covid-19 lockdown in the united arab emirates: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusseini, N.; Alqahtani, A. COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on eating habits in Saudi Arabia. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Cinelli, G.; Bigioni, G.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Bianco, F.F.; Caparello, G.; Camodeca, V.; Carrano, E.; et al. Psychological aspects and eating habits during COVID-19 home confinement: Results of EHLC-COVID-19 italian online survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftimov, T.; Popovski, G.; Petković, M.; Seljak, B.K.; Kocev, D. COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E.M.; Rauber, F.; Costa, C.D.S.; Leite, M.A.; Gabe, K.T.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Dietary changes in the NutriNet Brasil cohort during the covid-19 pandemic. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães Júnior, D.S.; Nascimento, A.M.; Santos, L.O.C.d.; Rodrigues, G.P.d.A. Efeitos da Pandemia do COVID-19 na Transformação Digital de Pequenos Negócios. Rev. Eng. Pesqui. Apl. 2020, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Quispe, F.Z.; Barragán Condori, M. El uso en exceso de las redes sociales en medio de la pandemia. Acad. Rev. Investig. En Cienc. Soc. Y Humanidades 2022, 9, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.C.; Ferreira, C.P.; Silva, C.M.d.; Medeiros, G.d.M.; Pacheco, G.; Vargas, R.M. Utilização das redes sociais em projeto de extensão universitária em saúde durante a pandemia de Covid-19 no 1. Expressa Extensão 2021, 26, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV). Brasil tem 424 Milhões de Dispositivos Digitais em uso, Revela a 31a Pesquisa Anual do FGVcia. 2020. Available online: https://portal.fgv.br/noticias/brasil-tem-424-milhoes-dispositivos-digitais-uso-revela-31a-pesquisa-anual-fgvciah. (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução n° 216, de 15 de setembro de 2004. 2004. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2004/res0216_15_09_2004.html (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Garcia, L.P. Uso de máscara facial para limitar a transmissão da COVID-19. Epidemiol. Serviços Saúde 2020, 29, e2020023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Azevedo, A.P.; Medeiros, F.P.; Souto, F.d.L.; Magalhães, A.F.C.; Leitão, L.d.S.; Cristino, J.S.; Assis, R.P.; Tavares, I.S.; Tamaturgo, D.d.S.; De Araújo, S.A. Adesão da higienização das mãos entre equipes multidisciplinar em unidades de terapia intensiva de um hospital referência em infectologia. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Enferm. 2021, 9, e5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequinel, R.; Lenz, G.F.; da Silva, F.J.L.B.; da Silva, F.R. Soluções a base de álcool para higienização das mãos e superfícies na prevenção da covid-19: Compêndio informativo sob o ponto de vista da química envolvida. Quim. Nova 2020, 43, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments 2021. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Lima, M.B.d.; Saturnino, C.M.M.; Tobal, T.M. Avaliação da adequação das boas práticas de fabricação em serviços de alimentação. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e433997418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organização das Nações Unidas (ONU). No Dia Mundial do Meio Ambiente, ONU Pede Fim de Poluição Plástica. 2018. Available online: https://news.un.org/pt/story/2018/06/1625911 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Lopez, M.P.V.; Freitas, P.O.; Vargas, S. Impactos da pandemia na hotelaria: Um estudo sobre os protocolos e desafios às políticas de sustentabilidade. Oikos 2022, 33, 0123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Bares e Restaurantes (ABRASEL). Como Retomar as Atividades: Recomendações e Cuidados Para uma Reabertura Segura de Bares e Restaurantes Diante da Crise 2020. Available online: https://redeabrasel.abrasel.com.br/read-blog/133_cartilha-como-retomar-as-atividades.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

| Reasons | T1 * | T2 * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Difficulty adapting the menu | 0 | 0 | 6 | 40.0 |

| Lack of customer adherence | 8 | 72.3 | 13 | 86.7 |

| Decrease in revenue | 7 | 63.6 | 13 | 86.7 |

| Lack of credit/bank loan | 2 | 18.2 | 5 | 33.3 |

| Difficulty structuring the delivery service | 4 | 36.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Difficulty maintaining the number of employees | 2 | 18.2 | 6 | 40.0 |

| Others | 4 | 36.4 | 4 | 26.7 |

| T0 | T1 | T2 | p * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Service Type | |||||||

| Dine-in consumption | 19 | 63.3 a | 11 | 36.7 b | 20 | 66.7 a | 0.001 * |

| Takeout | 19 | 63.3 | 23 | 76.7 | 23 | 76.7 | 0.344 |

| Delivery | 19 | 63.3 | 24 | 80.0 | 19 | 63.3 | 0.125 |

| Operating Hours | |||||||

| Increased | - | - | 2 | 6.7 | 5 | 16.7 | 0.453 |

| Decreased | - | - | 17 | 56.7 a | 8 | 26.7 b | 0.003 * |

| Unchanged | - | - | 11 | 36.7 | 17 | 56.7 | 0.210 |

| Number of Employees | |||||||

| Increased | - | - | 3 | 10.0 | 5 | 16.7 | 0.210 |

| Decreased | - | - | 13 | 43.3 | 6 | 20.0 | 0.070 |

| Unchanged | - | - | 14 | 46.7 | 19 | 63.3 | 0.180 |

| Revenue | |||||||

| Increased | - | - | 1 | 3.3 | 4 | 13.3 | 0.375 |

| Decreased | - | - | 29 | 96.7 | 23 | 76.7 | 0.146 |

| Unchanged | - | - | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10.0 | 0.250 |

| Profit | |||||||

| Increased | - | - | 0 | 0 a | 6 | 20.0 b | 0.031 * |

| Decreased | - | - | 30 | 100 a | 23 | 76.7 b | 0.003 * |

| Unchanged | - | - | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.3 | 1 |

| Advertising Means | |||||||

| Establishment websites/social media | 26 | 86.7 | 27 | 90.0 | 28 | 93.3 | 0.472 |

| Other websites | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 2 | 3.7 | 0.717 |

| Newspapers/Flyers | 7 | 23.3 | 6 | 12.9 | 6 | 20.0 | 0.276 |

| Radio/Television | 2 | 6.7 | 2 | 20.0 | 1 | 6.7 | 0.368 |

| Sound cars | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Billboards | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Others | 3 | 10.0 | 5 | 16.7 | 2 | 6.7 | 0.223 |

| Sales channels for delivery service | |||||||

| Phone | 19 | 63.3 a | 24 | 80.0 a | 4 | 13.3 b | <0.001 * |

| Messaging apps (WhatsApp and Telegram) | 18 | 60.0 a | 15 | 50.0 a | 10 | 33.3 b | 0.012 * |

| Food delivery apps | 13 | 43.3 | 13 | 43.3 | 14 | 46.7 | 0.926 |

| Establishment of websites, apps, and social media | 15 | 50.0 a | 13 | 43.3 a | 2 | 6.7 b | 0.009 * |

| None | 10 | 33.3 a | 3 | 10.0 b | 10 | 33.3 a | 0.007 * |

| Procedures | T0 | T1 | T2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Employee Care | |||||||

| Monitoring temperature and health | 16 | 53.3 | 16 | 53.3 | 14 | 25.9 | 0.794 |

| Mask use | 11 | 36.7 a | 25 | 83.3 b | 24 | 80.0 b | <0.001 * |

| Glove use | 20 | 66.7 | 21 | 70.0 | 26 | 86.7 | 0.109 |

| Frequent hand hygiene | 28 | 93.3 a | 18 | 60.0 b | 30 | 100 a | <0.001 * |

| Team training | 17 | 56.7 | 16 | 53.3 | 19 | 63.3 | 0.588 |

| Food and Environment Hygiene | |||||||

| Raw material packaging care (disposal/cleaning before storage) | 29 | 96.7 | 25 | 83.3 | 29 | 96.7 | 0.69 |

| Hygiene of fruits and vegetables before storage or preparation | 26 | 86.7 | 24 | 80.0 | 26 | 86.7 | 0.607 |

| Frequent cleaning of the environment, surfaces, and equipment | 28 | 93.3 | 22 | 73.3 | 26 | 86.7 | 0.97 |

| Cleaning of tables after each customer | 17 | 56.7 b | 11 | 36.7 a | 18 | 60.0 b | 0.046 * |

| Implementation of a Good Food Handling Practices Manual | 17 | 56.7 | 15 | 50.0 | 11 | 3.3 | 0.135 |

| Customer Care | |||||||

| Offering disposable cutlery and cups | 20 | 66.7 a | 18 | 60.0 a | 24 | 80.0 b | 0.02 * |

| Offering packaged cutlery | 20 | 66.7 | 17 | 56.7 | 20 | 66.7 | 0.500 |

| Offering customers gloves to select food | 2 | 6.7 a | 1 | 3.3 a | 6 | 20.0 b | 0.015 * |

| Customers serve their own plate | 6 | 20.0 | 4 | 13.3 | 7 | 23.3 | 0.247 |

| Plate served by restaurant staff | 25 | 83.3 | 20 | 66.7 | 24 | 80.0 | 0.223 |

| Monitoring customer temperature | 0 | 0 | 5 | 16.7 | 3 | 10.0 | 0.727 |

| Physical Structure Care | |||||||

| Measures to ensure physical distancing between people | - | - | 16 | 53.3 | 8 | 26.7 | 0.57 |

| Use of physical barriers at the buffet, cash register, scale, etc. | - | - | 8 | 26.7 | 4 | 13.3 | 0.388 |

| Use of sinks for customer hand hygiene | 14 | 46.7 | 10 | 33.3 | 16 | 53.3 | 0.097 |

| Availability of guidance materials for customers Availability of hand sanitizer dispensers | - | - | 13 | 43.3 | 7 | 23.3 | 0.70 |

| 14 | 46.7 b | 23 | 76.7 a | 25 | 83.3 a | 0.002 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souza, E.M.F.; de Carvalho, N.C.; Setti, I.B.; da Silva, R.R.; Liboredo, J.C. Changes in Food Service Operations in a Brazilian Tourist Area: A Longitudinal Approach to the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2025, 5, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080130

Souza EMF, de Carvalho NC, Setti IB, da Silva RR, Liboredo JC. Changes in Food Service Operations in a Brazilian Tourist Area: A Longitudinal Approach to the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID. 2025; 5(8):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080130

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouza, Eduarda Marcely Franco, Natália Caldeira de Carvalho, Iara Bank Setti, Rafaela Rosa da Silva, and Juliana Costa Liboredo. 2025. "Changes in Food Service Operations in a Brazilian Tourist Area: A Longitudinal Approach to the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic" COVID 5, no. 8: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080130

APA StyleSouza, E. M. F., de Carvalho, N. C., Setti, I. B., da Silva, R. R., & Liboredo, J. C. (2025). Changes in Food Service Operations in a Brazilian Tourist Area: A Longitudinal Approach to the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID, 5(8), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5080130