Abstract

A part of diversity management is working to achieve gender equality and create a comfortable working environment for women. However, in many organizations, gender biases and stereotypes frequently occur, consciously or unconsciously, regardless of whether women take on leadership roles. In addition, women must overcome a variety of challenges when taking on leadership roles or aspiring to become leaders. Based on the above background, we review and integrate the literature on management and career studies related to the challenges that women face in the process of advancing to leadership positions in organizations. Specifically, we examine the external and internal factors that create the various obstacles that women who aspire to leadership positions in structured organizations face from a gender perspective. Based on the integrative review, we discuss the implications for practices to increase the number of female leaders.

1. Introduction

Since the United Nations declared the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, the international community has been moving toward sustainable development. In particular, SDG 5 aims to achieve gender equality that is more evolved. Consistent with this goal, gender issues for women and female leaders have attracted much attention in recent years. Women in leadership play an essential role in gender equality. For example, women bring unique perspectives and experiences to leadership positions, leading to better decision-making, innovation that is more significant, and a work environment that is more positive [1,2]. Women leaders also tend to be more collaborative and inclusive, creating a work environment that is more positive and productive [3,4,5]. However, women face significant challenges in securing leadership positions, including bias, a lack of representation, and a lack of advancement opportunities [6]. For example, the low percentage of women in top management and on boards of directors is due not only to a biological gender obstacle but also to a socially constructed gender challenge [7,8,9]. We must recognize the value of women’s leadership in organizations and society as a whole and actively work to remove gender stereotypes and prejudices. This includes challenging traditional gender roles and promoting the idea that leadership is not limited to one gender.

Far from a desirable situation, the environment in organizations is often based on traditional gender roles, limiting leadership concepts to one gender. Indeed, in many organizations, gender bias is pervasive due to the gender stereotypes that are perpetuated by fixing expectations of what women should look like in the workplace [7]. Gender bias refers to the unequal treatment of individuals based on their gender [10], which can be either conscious or unconscious. Conscious gender biases are attitudes and beliefs about gender that individuals are aware of and intentionally express, whereas unconscious gender biases are unintentional and often outside a person’s awareness. Both forms of gender bias lead to discrimination, prejudice, and gender stereotypes (i.e., social assumptions about individuals based on their gender). Consequently, women face gender issues at every level in organizations, from being accepted to entry-level positions to leaving an organization [9].

Gender stereotypes are also prevalent in the career process, and women often encounter a glass ceiling in male-dominated workplaces. The glass ceiling is a formidable obstacle that impedes women’s career progression, which is primarily due to their perceived incongruity with higher management or leadership positions [11]. It represents a prevalent and deeply ingrained gender-based challenge that women encounter in their professional lives, which demands significant effort to surmount. Consequently, it is a persistent challenge for many women who wish to contribute to their organizations [12]. However, overcoming the glass ceiling does not guarantee an end to gender-based stereotypical challenges for women. Instead, women who attain leadership positions often encounter other leadership-specific stereotypes based on their gender, qualities, and abilities to lead effectively. These challenges reflect a broader societal tendency to equate leadership with masculine traits, often leading to negative perceptions of female leaders who do not conform to such expectations. Gender-based stereotypes represent a tremendous obstacle to women’s career advancement as leaders, demanding significant effort and perseverance.

In light of the aforementioned background, this integrative review aims to explore the external and internal challenges that female leaders face in their career advancement in organizations and to present an integrated model of the relationship that incorporates external and internal factors. Because organizations can significantly affect the careers and values of female leaders by making decisions based on gender biases and stereotypes, we examine the gender-related problems that women commonly encounter in the workplace and the influence that organizations have on women’s leadership careers by reviewing and integrating the literature on management and career studies related to challenges that women face when advancing to leadership positions. Based on the review, we propose an integrative model that illustrates the ways external and internal factors create barriers for women when they climb up the organizational hierarchy to become top leaders. Furthermore, we discuss the implications for practices that increase the number of female leaders.

2. External and Internal Challenges beyond the Glass Ceiling

2.1. Female Leadership Challenges as External Factors

Despite the increasing demand for diversity in career paths, gender discrimination in leadership remains persistent [13]. As a result, both men and women in organizations continue to face different career issues when focusing on their career advancement [7]. Men often benefit from a hidden phenomenon known as the “glass escalator”, which allows them to quickly advance and achieve higher positions, even in organizations that are dominated by women [14]. The glass escalator phenomenon reinforces gender stereotypes and makes it more difficult for women to attain leadership positions. Consequently, men are often favored over women in career advancement and obtain higher positions and salaries without facing the same obstacles as women [15].

In contrast, women must overcome general gender bias and stereotypes to break the glass ceiling and reach leadership positions in organizations. Even after breaking through this barrier, women face additional challenges that are based on leadership-specific biases and stereotypes, including leadership prototypes. Because many men are not satisfied with having women as leaders, women may intentionally be disadvantaged in certain situations throughout their careers [16]. Therefore, to be effective leaders, women must convince men of their leadership abilities [5,17]. Table 1 summarizes the major challenges faced by women who aspire to leadership positions.

Table 1.

Challenges women experience (external and internal factors).

2.1.1. Gender Biases and Stereotypes

Women must overcome general gender biases and stereotypes to break the glass ceiling and reach leadership positions in organizations, but in the process of doing so, they face additional challenges based on leadership-specific biases and stereotypes. Gender biases can be categorized into first-generation gender bias, which is a bias that is intentionally created by society and organizations, and second-generation gender bias, which is characterized by subtle and difficult-to-detect forms of unfair treatment of employed women relative to men, because it is not intentional and is often outside a person’s awareness [10,18,19]. First-generation gender bias often refers to conscious gender bias, the mistreatment of individuals based on gender, typically against women, and can lead to discrimination and prejudice in society and organizations [7,8]. Second-generation gender bias is an unconscious gender bias that is not intentional and is often outside a person’s awareness [20].

Both conscious and unconscious gender biases often occur at the time of entry into an organization, because the organizational structure in most organizations is characterized as masculine [9]. For example, the stereotype that women are less capable than men in a specific field can lead to discrimination against women in that field, even though they are equally adept [21,22,23]. Conscious gender bias manifests in many ways, including salary and promotion opportunities, and it is often caused by gender stereotypes, which refer to social assumptions that are made about individuals based on their gender [24]. In addition, because cultural beliefs create unconscious gender bias regarding workplace structure and supervision, they serve as an inadvertent and invisible barrier to women’s advancement that results from interaction patterns that favor men over women. Conscious and unconscious gender biases are often caused by gender stereotypes, leading to a narrow and limited understanding of each gender’s capabilities and the social expectations of how individuals should behave [7].

Gender stereotypes are beliefs and expectations about the characteristics and behaviors of women and men based on gender. These stereotypes are often culturally shared and can be reinforced by social institutions and interactions, such as the media, education, and family [25]. Two types of gender stereotypes occur: descriptive and prescriptive. Descriptive gender stereotypes identify gender-based attributes that cause misfits [7]. Under this type of gender stereotype, women are considered unfit for leadership positions. For example, agency is often considered a characteristic of male stereotypes, whereas communality is often considered a characteristic of female stereotypes. In many societies, women have been generally expected to be housewives with low social status who are unfit for the workplace [26].

Prescriptive gender stereotypes indicate that women promote and contribute to gender biases by imposing certain expectations and restrictions on themselves (“should” or “should not”). Because of this, discrimination against women persists even in workplaces where the gender ratio is equal [23]. The phenomenon of evaluating individuals based on preconceptions and stereotypes, commonly known as the lack of fit model, is a challenge faced by individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles and expectations [27]. Specifically, when a woman deviates from stereotypical gender norms, a lack of fit occurs between her and the role or task being evaluated. This reflects that the lack of fit model perpetuates societal expectations for gender roles, affecting evaluations of individuals who behave differently [7,27,28].

As an example of the challenges stemming from prescriptive gender prototypes, a woman who is assertive and takes on leadership roles may be perceived as less warm and likable than a woman with traditional feminine traits [8,18]. As a result, they may receive negative evaluations and discriminatory treatment, such as being passed over for promotions or not being recognized for their contributions. However, if a male assumes a leadership role, he is more likely to be evaluated as competent and effective because his behavior is consistent with gender stereotypes about masculinity [13,29]. These gender stereotypes lead to a hiring bias that favors men in male-dominated jobs and favors women in female-dominated jobs [30]. In essence, gender stereotypes create biases against women in their career advancement processes. In this way, gender stereotypes contribute to the prevalence of gender bias, and gender stereotypes in organizations play an important role in the journey and career of women leaders.

2.1.2. Glass Ceiling and Sticky Floor

The term “glass ceiling” generally refers to the invisible barriers within an organization that prevent women from being promoted to leadership positions [11,31]. This phenomenon can be seen as a unique obstacle for women, which hinders their upward mobility toward leadership roles and restricts their access to positions of authority and influence at higher levels within the organization. For women leaders to emerge, they often must overcome the glass ceiling, which is a persistent and systematic barrier [32].

This phenomenon can also be explained by the sticky floor phenomenon, where women who are unable or unwilling to overcome the glass ceiling find themselves confined to low-paying, female-dominated occupations with limited flexibility and a lack of opportunities for promotion [16]. The metaphor of a sticky floor emphasizes not encountering the glass ceiling, meaning that many women may not have the opportunity to advance beyond entry-level positions. In other words, the metaphor of a sticky floor suggests that many women may not be able to advance beyond entry-level positions, but it also suggests that some may be able to overcome these obstacles and reach higher positions. It would not be an exaggeration to say that overcoming the glass ceiling marks the beginning of a woman’s career as a leader [33].

2.1.3. Leadership Labyrinth

According to Eagly and Carli [33], even if women can overcome the glass ceiling, they must navigate a career labyrinth. While recognizing that women can succeed as leaders, the authors also highlighted that navigating the labyrinth of a career can be challenging due to the obstacles posed by gender-related hurdles. The metaphor of a labyrinth for women’s careers suggests that leadership and promotion for women may be difficult but are possible, and multiple paths to leadership that require effort, perseverance, and careful navigation could exist. In addition, various factors, such as gender stereotypes, organizational culture, and networks of interpersonal relationships, influence women’s promotion opportunities. For example, fixed notions such as women being unsuitable for leadership roles or that women should prioritize family over work perpetuate gender role stereotypes that hinder women’s advancement. Moreover, male-centric organizational cultures, along with policies and practices that favor male employees, impede women’s advancement. Furthermore, networks of interpersonal relationships play a crucial role in promotions, and women face challenges in building networks that are similar to those of men. In organizations where men predominantly hold leadership positions, it is often difficult for women to establish networks that would facilitate their promotion to similar positions [33].

2.1.4. Female Leadership Prototypes

The prototypes of women’s leadership styles in organizations are explained by the gender-social role theory, which states that gender differences arise from the social roles that men and women occupy in society [8,27]. The gender-social role theory explains how gender stereotypes develop and persist because it posits that individuals learn and internalize gender roles through socialization [34]. Agentic and communal attributes are aspects of gender roles that are particularly relevant to understanding leadership [6,35]. Agentic attributes are more strongly attributed to men than to women and primarily indicate a tendency to be assertive, dominant, and confident. In employment, proactive behaviors may include speaking assertively, following instructions, and competing with colleagues [8]. In comparison, communal attributes are more strongly attributed to women than to men and primarily indicate concern for the welfare of others (e.g., women’s welfare) and one’s ability to be affectionate, kind, gentle, sympathetic, interpersonally sensitive, nurturing, and tender [36]. Stereotypically, women are perceived as less competent leaders than men because women are perceived as non-traditional leaders. For example, Brescoll [37] discovered that gender and emotional stereotypes can undermine the success of female leaders. The belief that women are more emotional than men can unfairly bias the selection and evaluation of female leaders. Women are often seen as less capable of controlling their emotions and may face penalties for displaying emotions that convey power.

According to Giacomin, Tskhay, and Rule [38], people’s gender and social stereotypes influence their perception of individuals who appear to be leaders. The authors extracted mental representations of male and female leaders, as well as those of typical men and women (referred to as “non-leaders”). The results suggest that the mental representations of typical males and male leaders may overlap and that male stereotypes strongly align with the characteristics associated with leadership such as power. In addition, the faces of female leaders were perceived as more powerful than those of female non-leaders, whereas the faces of male leaders and non-leaders were perceived as equally powerful. This finding suggests that gender stereotypes may undermine the likelihood of success for female leaders. That is, the belief that women are more emotional than men can unfairly bias the selection and evaluation of female leaders. Indeed, women are often perceived as less capable of controlling their emotions and may face penalties for displaying emotions that convey power.

2.1.5. Think Manager–Think Male

In addition to gender stereotypes, the challenges that women face in leadership are explained by the think manager–think male attitude toward a leader’s competence and leadership style [39]. In organizations, men are favored due to the think manager–think male concept [21,22,40], which is based on subjective qualities of leadership [23,41]. In regard to gender roles that influence leadership behavior in organizations, female leaders are considered to be more interpersonally oriented, democratic, and transformational compared to male leaders [5]. Research has shown that men tend to adopt authoritarian and transactional leadership styles, which is consistent with the gender stereotype of men [42,43]. Authoritarian leadership is a powerful and directive style in which the leader makes decisions on behalf of the group and expects subordinates to comply. This leadership style is more closely related to traditional male gender roles and values, and male-oriented cultures tend to favor it. Men are more likely to be seen as influential leaders when they exhibit robust and assertive behavior. However, when women exhibit similar behavior, they may not be viewed favorably or considered suitable for leadership positions [43], suggesting that authoritarian leadership is more socially acceptable for men than it is for women. In contrast, transactional leadership—a leadership style that sets clear expectations and goals and uses rewards and punishments to motivate employees to meet those expectations and goals [29]—can be used by both men and women, although it is more closely related to traditional male gender roles and values [42,43]. Men tend to adopt this leadership style more often than women do, particularly in contexts where they are perceived as more masculine [26].

Fischbach, Lichtenthaler, and Horstmann [21] examined the emotional expression stereotypes associated with men, women, and successful managers using the think manager–think male paradigm. The results showed that men are more similar to successful managers in terms of emotional expression than women are. Women’s emotional expression is described differently from that of successful managers. Emotional stereotypes may negatively affect women’s leadership success because people believe that women lack the emotional expression qualities that are essential for leadership. However, for stereotypically masculine antagonistic emotions such as anger, women were not described differently from successful managers, indicating a potential shift toward a less stereotypically masculine view of leadership [21]. Ryan and Hassam [22] found gender and leadership stereotypes in the context of successful and failed firms. They found that the think manager–think male stereotype was positively correlated with leaders of successful firms and negatively correlated with leaders of unsuccessful firms. Specifically, they found that the ideal managers of successful firms were not associated with the think manager–think male stereotype, whereas the ideal managers of unsuccessful firms were stereotypically associated with women [22].

Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell, and Ristikari [23] contended in their meta-analysis that leadership stereotypes are culturally masculine. That is, they found that leadership was strongly and consistently viewed as culturally masculine across the various paradigms used in the analysis. The authors suggested that the masculine nature of leadership roles contributes to prejudice against female leaders because men are more likely to conform to cultural interpretations of leadership, have easier access to leadership roles, and therefore face fewer challenges to succeeding in those roles. Therefore, the think manager–think male stereotype is still prevalent and can adversely affect women’s career opportunities. In short, the think manager–think male stereotype focuses on male managers and contributes to gender inequality in the workplace [23].

2.1.6. Think Crisis–Think Female

In contrast to the think manager–think male concept, where people tend to associate effective managerial and leadership roles with masculine traits and characteristics, think crisis–think female refers to the stereotype that women are better suited to deal with crises and difficult situations. This stereotype is based on the gender stereotype that women are supposed to raise children and care for them [22].

Ryan, Haslam, Hersby, and Bongiorno [22] investigated the think crisis–think female phenomenon and its relationship with the think manager–think male stereotype. Their results supported the existence of the think crisis–think female phenomenon, indicating that women were more likely than men to be chosen as leaders during times of crisis. This may be because crises require different leadership qualities than those typically associated with male leaders. Furthermore, the authors found that the think manager–think male stereotype was not always present and that its strength varied depending on the context of the crisis. Specifically, the stereotype was weaker when the crisis was seen as more severe and requiring more drastic action. Their finding suggests that the think manager–think male stereotype may be more flexible than previously thought and that contextual factors can influence its strength [22].

Kulich, Gartzia, Komarraju, and Aelenei [44] investigated how gendered traits, gender, and the type of crisis affected the perception of leaders’ suitability for crisis leadership roles. The results supported the think manager–think male stereotype, indicating that men were perceived as more suitable for leadership roles than women were. However, the think crisis–think female stereotype was not supported, and gendered traits such as assertiveness and empathy were found to be more influential in determining suitability for crisis leadership roles. They concluded that gendered traits significantly influence the perception of leadership suitability in crises, but the influence of gender is context-dependent. The study suggests that addressing gender biases in leadership requires a nuanced understanding of the complex interactions between gendered traits, gender, and situational factors [44].

2.1.7. Double Bind

Women who adopt a leadership style based on gender stereotypes may be better role models and may perform better [41,45]. However, women may face a double bind due to societal gender stereotypes that either limit their behavior and meet gender-based expectations or challenge those expectations and confront them with two conflicting options [19,46]. When women take on leadership positions, they may be confronted with two conflicting options due to societal gender stereotypes. First, women are expected to assert themselves and appear masculine to be considered competent, but if their behavior is viewed as too assertive, they may be perceived as unlikeable. Second, if women’s behavior is too feminine, they may be perceived as likable but incompetent [39]. The double bind is a very difficult situation, especially in a male-dominated environment, because women may be perceived as more effective in adopting traditionally masculine leadership styles. Moreover, women are more likely to conform to gender stereotypes in their interactions with others, which may also affect their leadership styles [19,41]. For example, social interactions in organizations may influence how female colleagues perceive and shape their behavior. That is, women with a strong feminine self-concept are more likely to adopt a transformational leadership style, whereas men with a strong masculine self-concept are more likely to adopt a transactional leadership style [16]. Thus, the leadership styles that women are more likely to adopt are explained as being based on gender stereotypes.

One of the ways that women can overcome the double bind is to adopt leadership styles that are both effective and non-masculine. Research has shown that two of the most effective leadership styles, transformational and servant leadership, are better suited for women [42,47,48]. Transformational leadership leverages emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills to build strong relationships with followers [42,49], effectively increasing employee job satisfaction, commitment, and performance. Furthermore, it is believed to promote leader behaviors that emphasize follower well-being through care, intellectual stimulation, and individualized attention. Thus, both male and female employees perceive transformational leadership as an effective leadership style [42], but one that is particularly effective for female leaders. Servant leadership values community (e.g., prioritizing followers and stakeholders) in ways that are not typically seen in more traditional forms of leadership [50]. Servant leaders prioritize the needs and growth of their followers over their selfish goals or power ambitions, thereby promoting implicit advantages for female leaders in employee management [51]. In addition, the communal leadership style adopted by female leaders supports finding meaning in their work [52]. It was found that women’s transformational leadership is as effective as men’s [53], and servant leadership positively affects women’s adaptability and performance [26,41,48,54]. Thus, women’s socially preferred leadership style can be established based on gender stereotypes, where they are expected to be competent and positively influence the company. However, men tend to have a born-to-be-a-leader bias and prefer male bosses over female bosses [8].

2.1.8. Backlash

In the context of gender stereotypes and leadership, women are expected to exhibit masculine traits and behaviors to be seen as influential leaders. However, being too assertive may cause one to be perceived as unlikeable, whereas having too many feminine traits and behaviors may cause one to be perceived as incompetent [55]. As a result, women who behave in a masculine way to be recognized as leaders face a backlash in which they are punished for violating gender norms [56]. Backlash in the gender context refers to the adverse reaction that some men have to the changing roles and expectations of women in society. The backlash reinforces some men’s traditional attitudes and behaviors toward women, which may ultimately harm women’s progress and rights [11].

The backlash is more robust against women with masculine jobs and positions and against women with masculine behaviors [28]. Women who aspire to leadership positions must act proactively to counter the lack of fit between gender and leadership roles, but implicit biases may limit their actions to meet gendered or challenging expectations, with pushback from colleagues and subordinates. Gender stereotypes are at work here, for example, where women are compared to men and assumed to be emotional and powerless. Gender stereotypes also influence the decision to take leadership positions that are more likely to be adopted by men or women. Therefore, women need to emulate men’s leadership styles to succeed in the workplace [29]. However, women are caught in the dilemma of needing to appear competent, challenging, and determined while also needing to be more feminine, etc. Thus, when women demonstrate competence and behavior that is equal to that of men, other women may treat them as outsiders and subject them to criticism and prejudice. These stereotypes create mismatches and make it difficult for women to achieve success in leadership positions [8,57].

Burke [56] examined backlash in the workplace by examining employee views on employer support for the promotion of women, people with disabilities, Indigenous people, and racial/visible minorities. The results showed that male employees who supported backlash tended to have longer tenure and lower organizational levels [56]. Ciancetta and Roch [58] conducted a study on the expression of feedback in performance appraisals for women in organizations. Their results indicated that the backlash effect was evident in the feedback expressions used in performance appraisals for women at all levels of the organization, not just women in leadership roles. The study also found that women were less sensitive to using backlash-related words and that they shaped their behavior toward gender role norms through positive feedback [58].

Backlash also negatively affects women’s relationships with other women because it can create a division between women who have been successful in male-dominated environments and those who have not. Successful women may distance themselves from the women’s movement or stay away from their careers, whereas less successful women may be less interested in career advancement.

2.1.9. The Lack of Leadership Development

Pater, Van Vianen, and Bechtoldt [59] suggested that one reason why women are less likely than men to be assigned challenging tasks is that bosses tend to assign more challenging tasks to male subordinates than to female subordinates. The findings support the idea that women are deprived of important opportunities for development by their bosses, which may further perpetuate gender inequalities in social practices within organizations. Because challenging experiences are critical to employee learning, growth, and career advancement, fewer opportunities for self-development for women compared to men can limit career advancement opportunities and hinder overall career development. Giving leadership development opportunities to women would produce better outcomes. For example, Stichman, Hassel, and Archbold [60] showed that increasing the number of female police officers who received sufficient leadership development improves their performance within the organization and brings diverse perspectives and experiences.

Samuelson, Levine, Barth, Wessel, and Grand [61] showed that the gender inequality in development opportunities creates a sticky floor effect. Despite having similar desires for high-status and high-responsibility development opportunities, women are often assigned less challenging or less important tasks compared to men. This disparity in opportunities has resulted in a low representation of women in leadership positions. These tendencies are attributed to stereotypical beliefs about women, such as the belief that women need protection, are less capable of agency-like tasks, and are thus less likely to succeed in challenging assignments. King, Botsford, Hebl, Dawson, and Perkins [62] found that so-called “good sexism”, which treats women as defenseless and limits their capacity, plays a significant role in women’s access to leadership development opportunities. Experiencing forms of paternalistic protection can negatively affect a woman’s perception of herself. If others perceive women as needing protection from difficult situations, it can lead women to doubt their abilities to perform well in such situations, resulting in poorer performance on challenging tasks.

2.1.10. Glass Cliff

Beyond the glass ceiling phenomenon, women face the think crisis–think female effect based on the stereotype that women are more likely to be appointed to precarious leadership positions, such as in companies facing decline or crisis because they have better crisis management skills. This stereotype is based on gender stereotypes that associate women with nurturing and caring qualities.

Stereotypes due to the think crisis–think female effect create a glass cliff. The glass cliff refers to placing women in leadership positions when a company is experiencing a downturn. In other words, women tend to be appointed as leaders in times of crisis [22,63,64]. The glass cliff phenomenon suggests that women in leadership often face crises or challenging situations that make it difficult for them to attain the same status as men. In these precarious positions, female leaders must work hard to find solutions and become heroes for their organizations if they wish to succeed. However, they are also at high risk of being held responsible if they fail.

Morgenroth, Kirby, Ryan, and Sudkämper [45] conducted a meta-analysis on the glass cliff phenomenon. Analyzing data from 113 studies conducted between 2004 and 2018, their meta-analysis supported the existence of the glass cliff phenomenon, indicating that women are more likely than men to be appointed to precarious leadership positions during times of crisis. The authors suggested that although women may be seen as less qualified for leadership roles during normal times, they may be viewed as more suitable during times of crisis when traditional leadership qualities are perceived to be less effective [45].

Ryan and Hassam’s [64] two experimental studies showed that participants were more likely to choose a female candidate for a leadership position in a company facing a crisis or decline, which the authors attributed to gender stereotypes associating women with nurturance and caring [64]. Other studies have shown that women are more likely to be appointed to high-risk CEO positions than men are [51,52]. In addition, Ryan and Haslam [63] investigated the pre- and post-appointment performance of men and women who were appointed to boards of directors. The study found that when firms appointed women to the board during a period of decline in the overall stock market, their performance tended to be consistently worse in the preceding five months compared to firms that appointed men. This suggests that the glass cliff phenomenon may result in a higher probability of women being appointed to leadership positions during periods of crisis or poor performance, as well as women being appointed to boards before and after their appointments [63].

Cook and Glass [65] studied the career trajectories of all women who have served as CEOs in the Fortune 500 based on two sets of data: a comparison of their career trajectories with a matched sample of male CEOs and in-depth interviews with female executives in various fields. Their analysis revealed that women are more likely than men to be promoted to high-risk leadership positions and often need more support and authority to achieve their strategic goals. The study also showed that men can influence an organization’s job performance through confidence, whereas women can only influence their performance through a combination of self-confidence, high performance, and prosocial motivation (e.g., demonstrating motivation to benefit others) [66]. When men are appointed as CEOs, they often hold a powerful position with great status on the board of directors, high power, and a wealth of resources, whereas when women are appointed CEOs, they do not concurrently hold other influential positions, making them increasingly vulnerable to monitoring and performance pressures [67].

2.1.11. Queen Bee Syndrome

Women who have overcome various leadership challenges may feel pressure to cling to their position and maintain a sense of self-worth to increase their chances of promotion. However, this can create difficulties among other senior and junior women in the workplace because successful female leaders exhibit more masculine leadership characteristics, such as distancing themselves from other women and emphasizing competitiveness and assertiveness [68]. This phenomenon is called the “queen bee syndrome.” The queen bee syndrome can be explained by social identity theory, in which female leaders feel different to other women and choose to distance themselves and justify gender inequality. For example, as women advance in their careers, they may become more assertive and adopt more masculine traits. Gender bias and gender stereotypes received from others interact with gender roles and self-worth: a queen bee phenomenon [69]. Although women try to distance themselves from stereotypes to avoid being disadvantaged in their careers [55], female leaders who do not distance themselves from their female subordinates are more likely to be supported by their subordinates.

Because female leaders make many sacrifices to succeed in their careers, they need to recognize that they are more committed to their careers and are more masculine than other women. These attitudes and behaviors effectively advance an individual’s career in an environment where their career options are limited. However, in male-dominated workplaces where female role models are needed, junior women may lose motivation for career advancement if some women act as though they are the queen bee [70,71]. The queen bee phenomenon results from gender discrimination caused by the harmful gender stereotypes that women face. These challenges threaten women’s career advancement and have little to do with women’s abilities or ambitions [70,71].

Yoshikawa, Kokubo, and Wu [72] found that women who self-identified as women early in their careers shifted to asserting their masculinity as their careers progressed. In other words, female managers who were less gender-identified at the start of their careers and subsequently experienced more gender discrimination had higher self-ratings of some dimensions of the queen bee phenomenon indicators. Conversely, female managers with high levels of gender identity at the start of their careers and who subsequently experienced a high degree of gender discrimination had the same or lower levels of queen bee phenomenon indicators than female managers who did not experience much of such discrimination [72]. Contrary to the queen bee syndrome, some researchers have argued that if top management is female, women are often chosen for middle management positions as well, which has a positive effect on the status of women because women influence them as role models [73].

Derks, Ellemers, van Laar, and Groot [74] surveyed 94 women in senior positions in Dutch companies. Based on the social identity theory, they assumed that the queen bee phenomenon is an individual coping response of low gender identity women to gender discrimination in the workplace. They found that the queen bee phenomenon is not due to inherent female tendencies but to contextual social conditions such as gender discrimination and gender identity threats. They also found that women who reported a low gender identity and experienced high levels of gender discrimination when entering the workforce were more likely to exhibit the queen bee phenomenon to pursue their ambitions within a sexist organizational culture. This finding suggests that the queen bee phenomenon is a response to external pressures rather than an inherent aspect of female behavior [74].

Faniko, Ellemers, Derks, and Lorenzi-Cioldi [75] studied the origin and consequences of the queen bee phenomenon, in which successful women in male-dominated organizations do not support the promotion of junior women, thereby explaining female managers’ opposition to gender quotas. The authors suggested that senior women who have made difficult choices for organizational advancement may expect junior women to make similar sacrifices for their career success. However, female managers are not competitive toward women of the same rank and favor a quota system that would benefit women with whom they would be in direct competition. This finding challenges the common understanding that the queen bee phenomenon reflects the general awkwardness of women competing with each other in the workplace. Furthermore, the authors concluded that the queen bee phenomenon should be less likely to occur in organizations where women face fewer difficulties achieving their career aspirations [75].

2.2. Female Leadership Challenges as Internal Factors

2.2.1. Self-Gender Stereotypes

Self-gender stereotypes are defined as the development of gender-stereotypic attitudes and behaviors under the influence of organizational gender stereotypes (i.e., internalizing gender stereotypes). Specifically, even if women overcome various challenges, such as the glass ceiling, women leaders tend to internalize self-gender stereotypes. However, they are less likely to realize that they have internalized self-gender stereotypes. Gender stereotypes are important for women’s self-evaluation, career choices, and self-efficacy. Research has shown that women tend to underestimate their leadership abilities and have lower self-efficacy than men [76]. This is particularly evident in male-dominated fields where women are underrepresented, leading to feelings of isolation and a loss of confidence. Women feel pressure to conform to gender expectations regarding their behavior and communication style, leading them to underestimate their performance and leadership abilities and reducing their self-efficacy [40,77], which can affect their success in the workplace. Low self-efficacy in women is related to self-gender stereotypes.

Self-gender stereotypes suggest that gender stereotypes affect how women perceive themselves, which relates to their identity, self-esteem, and self-confidence, so women must be confident in their abilities and achievements [66,78]. For example, when women’s leadership styles are constrained by socially prescribed roles and stereotypes, it may decrease their self-efficacy. However, when women’s leadership styles are more flexible and collaborative, their self-efficacy will likely increase. In addition, it has been suggested that transformational leadership may be a leadership style more commonly adopted by women because it aligns with traditional feminine gender social roles [79]. Moreover, when women’s leadership styles are more flexible and collaborative, their self-efficacy will likely increase. This outcome occurs because social constraints inhibit women’s self-efficacy. Other studies have shown that mentoring and coaching can effectively facilitate women’s leadership development and increase their self-efficacy [42,80].

Research on self-gender stereotypes has suggested that women tend to accept discrimination and prejudice toward women based on gender stereotypes. For example, whereas men tend to overestimate how others see them, women tend to underestimate how others see them. Braddy, Sturm, Atwater, Taylor, and McKee [24] contended that implicit biases against women still exist in organizations, specifically in the way that different outcomes may emerge for men and women leaders when their self-ratings differ from others’ ratings. Their results showed that women who overrated their leadership behaviors received lower performance ratings and higher perceived risk of derailment scores from their supervisors than women who underrated their leadership behaviors. However, men experienced fewer negative consequences when they were overrated. They suggest that this bias against women leaders stems from gender stereotypes and the role congruity theory of prejudice. Women who underrate their leadership behavior may receive better outcomes [24].

Another study on self-gender stereotypes by Morgenroth, Ryan, and Sønderlund [81] investigated the dynamic interaction between the internal and external factors that affect individuals’ decisions to make sacrifices for career advancement, focusing on women in the male-dominated fields of surgery and veterinary medicine. The results from two intense studies indicated that women were less willing to make sacrifices for their careers than men were, which was attributed to frequent experiences of sexism and incompatibility with professional superiors. The authors also found that structural conditions in the workplace may influence the perception of probabilities of success differently for men and women, even though the decision-making processes are similar [81].

2.2.2. Tokenism

Tokens are individuals who belong to a minority group that is numerically smaller than the majority group and whose culture is controlled and shaped by the majority. Tokenism not only subjects individuals to pressure to conform to gender stereotypes but also imposes psychological burdens such as the perception of needing to outperform male colleagues and the pressure of being seen as a representative of women in the workplace [67]. In addition, due to limited opportunities for experience and skill development resulting from stereotypes, an individual’s leadership skills may not be fully developed. Consequently, women who are tokens in the workplace often perceive the organizational atmosphere as unfair, and their token status becomes an internal factor that increases the likelihood of women leaving an organization [82].

In a qualitative study on gender-based tokenism in both female and male occupations, Benan and Olca [83] concluded that being a minority in itself does not directly lead to tokenism, but it does affect the social division of labor between men and women. Not all members of the so-called dominant majority create a limiting situation, and other factors influence the token experience. However, both female and male tokens face professional dis-harmony and difficulties in the presence of dominant groups. Women who experience occupational mismatch have limited opportunities for promotion and advancement, whereas men in similar conditions tend to achieve these opportunities more quickly. Interestingly, only men were found to experience the manipulation of token status and turn it into token gains, whereas women still faced lower status compared to men.

2.2.3. Gender Stereotype Threat

The gender stereotype threat is similar to tokenism. This is the phenomenon where individuals experience anxiety and fear of confirming negative gender stereotypes when performing tasks that are believed to be associated with their gender, which can hinder individual performance and aspirations [30]. The gender stereotype threat has been demonstrated to undermine women’s performance, especially in STEM fields and leadership jobs [84]. For example, if a woman belongs to a traditionally male-dominated field, a stereotype threat may undermine her interest and reinforce her belief that she does not belong in that field. Furthermore, those with minority social identities are vulnerable to stereotype threat, and in the right social context, stereotype threats can affect the performance and aspirations of any group. For example, males are more vulnerable to stereotype threats in social contexts that require emotional sensitivity, whereas females are more vulnerable to stereotype threats in male-dominated fields. If a stereotype threat is responsible for women’s poor performance in traditionally male-dominated fields, then eliminating the threat from the workplace may help eliminate gender inequality [77].

Davies and Spencer examined the effects of stereotype threats on women’s ambitions and their positions of power. They exposed women who were sensitive to stereotype threats to gender-related stereotype commercials and then had them perform a leadership task to investigate whether women would choose subordinate roles over leadership positions. The results showed that the commercials activated female stereotypes in sensitive women and lowered their ambitions for leadership. This effect did not occur in an identity-safe environment. Activating female stereotypes affected women’s aspirations for leadership, but this effect can be mitigated by an identity-safe environment [85].

Hoyt and Murphy argued that the response to threats to women’s identity depends not only on individual factors but also on important interpersonal factors. In particular, role models for women can be important in protecting them from identity threats in leadership roles. Successful women can demonstrate that women can succeed in fields related to stereotypes, and role models can enhance social belongingness and protect against identity threats. However, role models can also have contradictory effects. Comparing oneself to a successful person can inspire and provide hope, but it can also emphasize one’s flaws. Role models can be useful in protecting against stereotype threats in the field of leadership and can play a beneficial role for women [77].

2.2.4. Gender Stereotype Internalization

Gender stereotype internalization refers to the process by which social roles, characteristics, behaviors, and expectations based on gender stereotypes permeate and internalize an individual’s attitudes, values, behaviors, and self-evaluations [86]. Women tend to make career choices that are influenced by gender biases. For example, a negotiation also has a gender stereotype aspect [87]. Men tend to negotiate more frequently than women do, and a stereotype is that women have lower negotiation skills and are less likely to negotiate. Women who have internalized gender stereotypes may believe that they are incapable of assuming leadership roles or that their skills are inadequate.

Hentschel, Braun, Peus, and Frey [88] revealed how recruitment advertising affects women’s willingness to work. Women tend to perceive a lack of fit in masculine careers and positions, leading to negative performance expectations and self-limiting decisions in their career choices. The authors found that using feminine language in recruitment advertisements is a practical starting point for promoting women to higher organizational positions. However, women’s lack of confidence in their abilities and achievements can contribute to gender inequality in the workplace. Women tend to underestimate themselves in leadership competencies and have lower self-efficacy. Women’s self-perception can perpetuate gender stereotypes, leading to identity underestimation and a lack of confidence [88].

To examine the effect of gender stereotype internalization, Fritz and van Knippenberg [89] investigated the effects of a supervisor’s gender, support, and job control on the leadership aspirations of male and female employees. The authors surveyed 393 employees from various industries in the Netherlands. Their findings revealed that female employees reported lower levels of leadership aspiration than their male counterparts did, mainly when their supervisor was male. However, the gender gap reduced significantly when female employees had a female supervisor. They also found that job control played a significant role in the relationship between the supervisor’s gender and leadership aspiration. Female employees with a male supervisor reported lower levels of job control, leading to lower levels of leadership aspiration, but this was not observed among male employees [89].

The research described above suggests that women who have internalized gender stereotypes may believe that they are incapable of assuming leadership roles or that their skills are inadequate [6,90]. For example, women’s gender identity may affect their leadership identity. Female leaders may interpret their gender identity positively, which reduces identity conflicts and increases happiness, and they may perceive leadership as an attractive goal rather than an obligation [91]. Women’s self-perceptions may perpetuate gender stereotypes, leading to an underestimation of their identity and a lack of self-confidence. Women’s self-identity, self-efficacy, and underestimation of themselves are important factors in the career development of women leaders, in addition to the number of opportunities and power provided by the organization.

3. The Integrative Model

3.1. Gender Stereotypes as Internal Factors

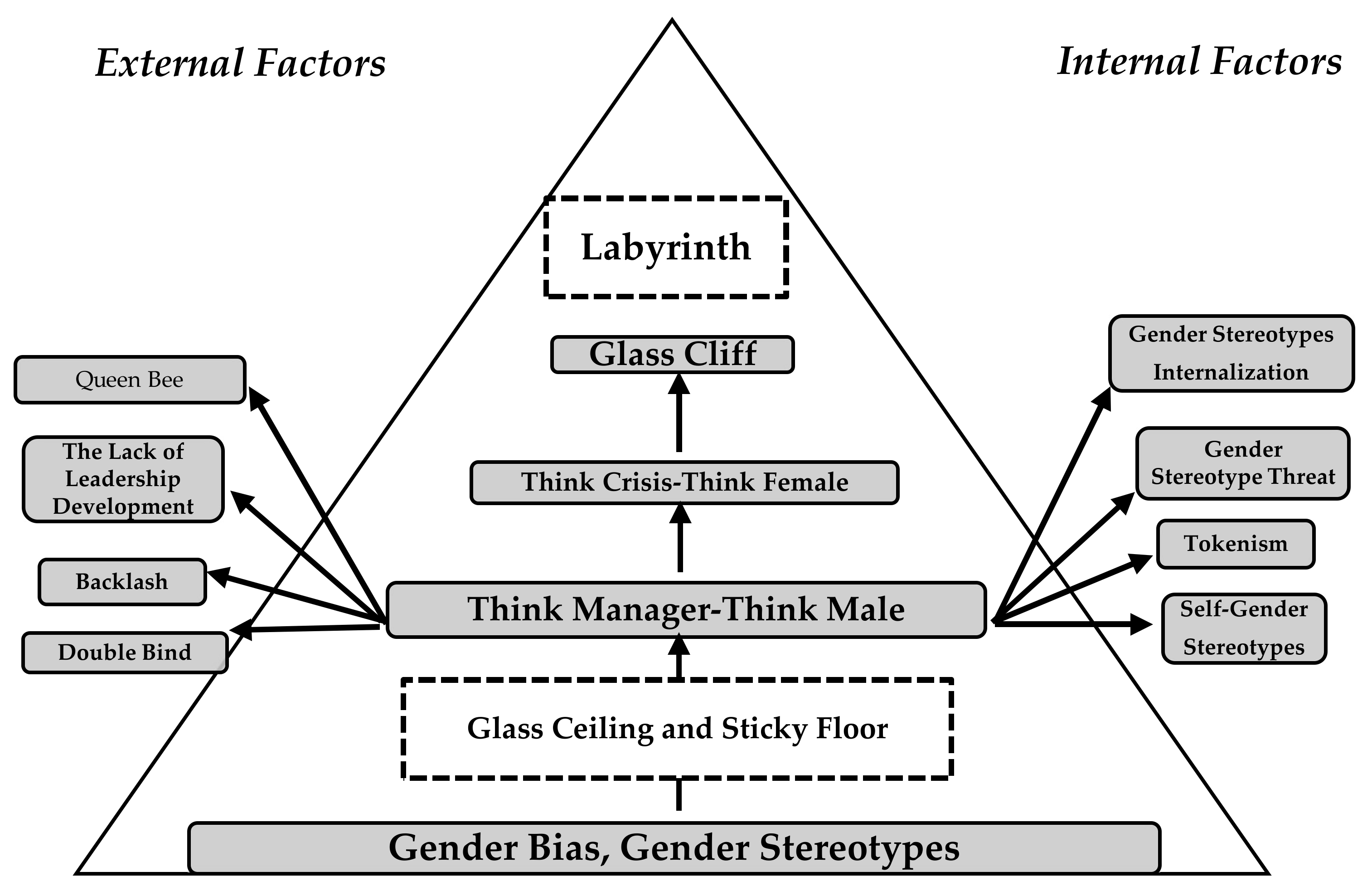

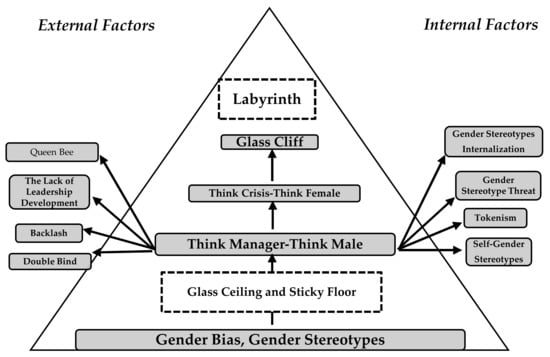

Based on the literature that we have reviewed so far, we developed an integrative model that summarizes the external and internal factors that create the barriers that female leaders face in their careers and as leaders within organizations. Figure 1 illustrates the integrative model. The model shows that the challenges that women face in their careers are driven by general types of gender biases and stereotypes, beginning at the point of entry into the organization and continuing through the early stages of their careers.

Figure 1.

An Integrative Model: Challenges Women Experience in Organizations.

Although women generally face challenges stemming from gender bias and stereotypes, women who aspire to leadership positions encounter additional leadership and personal career challenges. As a result, gender bias and stereotypes prevail throughout women’s careers at all levels, creating various challenges in their career trajectories within organizations [7,8]. Our model also suggests that many organizations are structured as masculine from the gender perspective. The gender stereotype-based structure of organizations can influence the perceptions and behavior formation of male and female leaders, even though nothing is inherently gender-related about them [5]. In other words, gender bias and stereotypes within organizations implicitly determine what women should and should not do, which creates both external and internal factors that affect women’s leadership careers.

3.2. External Factors Affecting Women’s Leadership Careers

Figure 1 depicts the various stages that women encounter in their career progression that are influenced by gender biases and stereotypes. To become leaders at each stage, women must first overcome the glass ceiling. Failure to do so will result in them remaining in low positions on the sticky floor. Even if they do succeed in shattering the glass ceiling, they advance into the labyrinth, where they encounter additional gender stereotype-based selection biases. The figure also suggests that in organizations, various selection biases based on the think manager–think male phenomenon tend to place men in desirable leadership positions and women in undesirable leadership positions. The think manager–think male biases are the major cause of double bind, backlash, lack of leadership developments, and the queen bee syndrome, all of which hinder the growth of female leaders.

Based on the notion of men as leaders, women face the double bind of contradiction with societal gender-stereotypical expectations. This contributes to backlash when women behave differently from gender stereotypes. The backlash has negative consequences such as punishment or reinforcing traditional attitudes and behaviors toward women. Due to the double bind and backlash, women oscillate between masculine (assertiveness, competitiveness, etc.) and feminine (compassion, empathy, etc.) traits that are necessary for leadership, and they are subjected to social pressure to decide which traits to emphasize. In addition, because women are not seen as leaders compared to men, organizations can lack leadership development, where contributions to and support for leadership development and capacity building are not provided. Furthermore, male-dominated organizations are more prone to the queen bee phenomenon, contributing to maintaining a glass ceiling in the organization.

Even after women break through the glass ceiling and they are chosen as leaders, they find themselves near the glass cliff in the labyrinth of their careers. The think crisis–think female effect contributes to a glass cliff for female leaders. In addition, because women often work for less compensation than men with comparable experience and skills, organizations may exhibit selection bias in favor of women in dangerous situations [14,64]. Therefore, women tend to be placed in a disadvantaged or precarious position, even when a higher status is granted [64]. Women leaders are not only expected to possess skills that are on par with their male counterparts, but also to demonstrate leadership styles that are indicative of their suitability as leaders.

Gender biases and stereotypes persist, and women who break through the glass ceiling and survive the glass cliff still face the labyrinth of their careers. The selection bias of the think manager–think male or think crisis–think female phenomenon does not disappear simply because a woman has been chosen as a leader. Therefore, women leaders must perform under adverse conditions and in precarious positions. If they can overcome the glass cliff and labyrinth, they can earn respect as leaders. However, if they cannot overcome these obstacles, they may lose confidence, perceive themselves as incompetent, internalize gender stereotypes, and consequently shift from external factors to internal factors.

3.3. Internal Factors Affecting Women’s Leadership Careers

Figure 1 shows that gender biases and stereotypes developed from an organization’s influence on women’s self-perceptions and values of unfitness to lead, leading to gender stereotype internalization. This leads to female leaders self-limiting their career choices because they believe they cannot fulfill leadership roles. For example, women leaders tend to behave in ways that are consistent with gender stereotypes. Therefore, even when women overcome the glass ceiling, it leads to a lack of confidence in their leadership presence.

Tokenism suggests that women aspiring to leadership positions feel pressure to prove themselves and perform at a higher level than their male counterparts to justify their position. This pressure can lead to anxiety and stress, and it could potentially affect their performance and ability to lead effectively. They may lose confidence, feel like an imposter, and further affect their performance and self-esteem. They may also be subjected to gender stereotype threats to attain those positions because social stereotypes expect men to be the leaders, which may cause women to lose confidence and feel that they do not belong to the leadership field. As a result, women tend to internalize self-gender stereotypes, which can further result in their gender-stereotypical identities [90], a lack of confidence in their abilities and achievements [66,78], and a lack of leadership skills and assertiveness [76].

In summary, both the external and internal factors derived from gender stereotypes become factors that limit women’s leadership and careers. Therefore, to build a career as a female leader, it is necessary to challenge gender stereotypes based on the concept of leadership [92].

3.4. Vicious Cycle That Manifests Leadership Challenges for Women

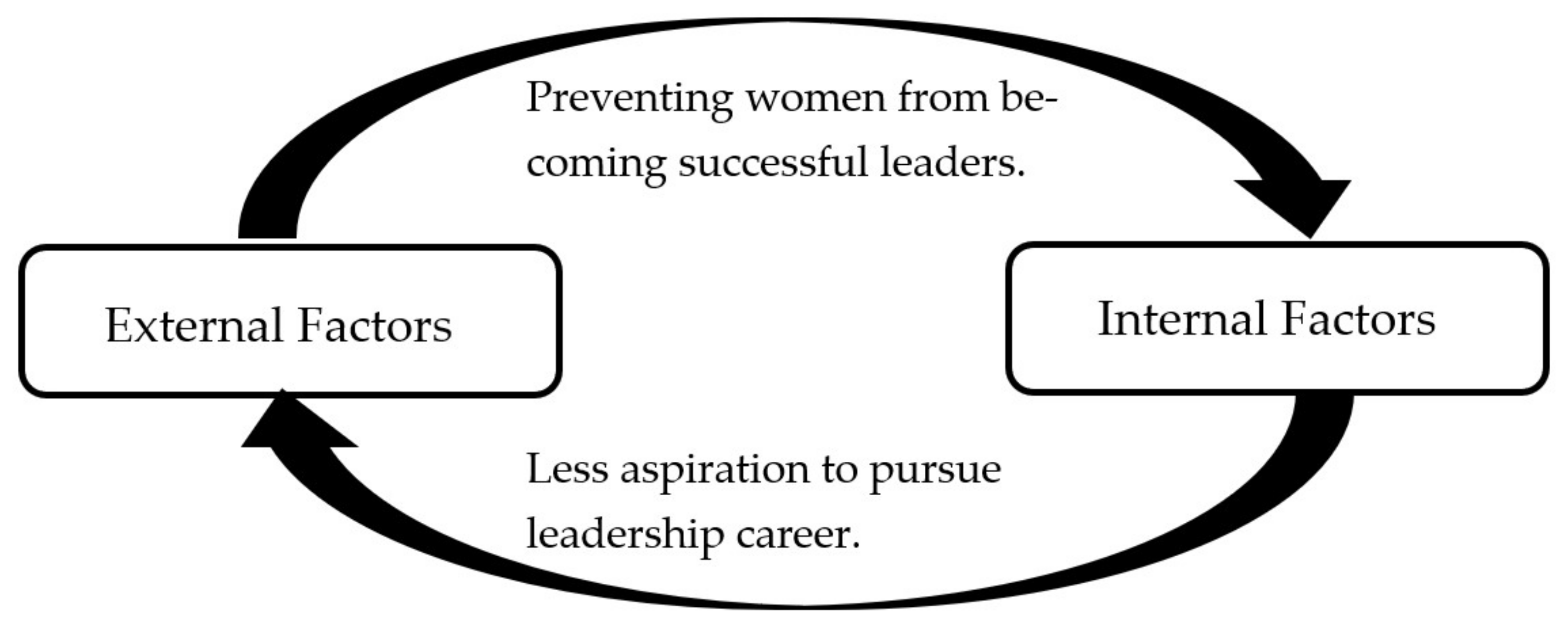

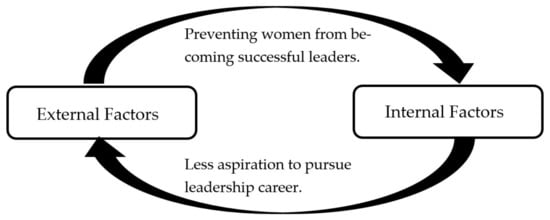

As shown in the above section, both the external and internal factors based on gender stereotypes have a negative effect on women’s careers. Figure 2 shows that external factors such as gender bias and gender stereotypes within organizations may cause women to underestimate themselves and their self-efficacy [80], which causes a vicious cycle in which challenges to women in leadership manifest over time. For example, although organizations are responsible for appointing women to leadership positions and offering promotion opportunities, gender stereotypes and biases within the organization increase the possibility that women are appointed to disadvantageous or unstable positions due to unfavorable organizational conditions. Therefore, when women are appointed to leadership positions, the organization may judge women more harshly than men. This accelerates the internalization of gender stereotypes among female leaders such that they feel incapable in leadership roles or that their skills are inadequate. Female leaders may believe that they are not qualified for career positions [6,90], leading to the underestimation of their leadership identity and a lack of self-confidence.

Figure 2.

Vicious cycle between external and internal factors.

The internalization of gender stereotypes and the resultant low self-confidence and low performance as leaders, as well as the avoidance of leadership roles and self-limitations of career choices, further reinforce the gender biases and stereotypes within organizations, which stabilize and even strengthen the external factors that prevent women from pursuing leadership roles. The repetition of this vicious cycle can limit the possibility of women being appointed to leadership positions and restrict their career growth. Therefore, if organizations make decisions based on gender stereotypes, they cannot expect women to excel and succeed in top management positions.

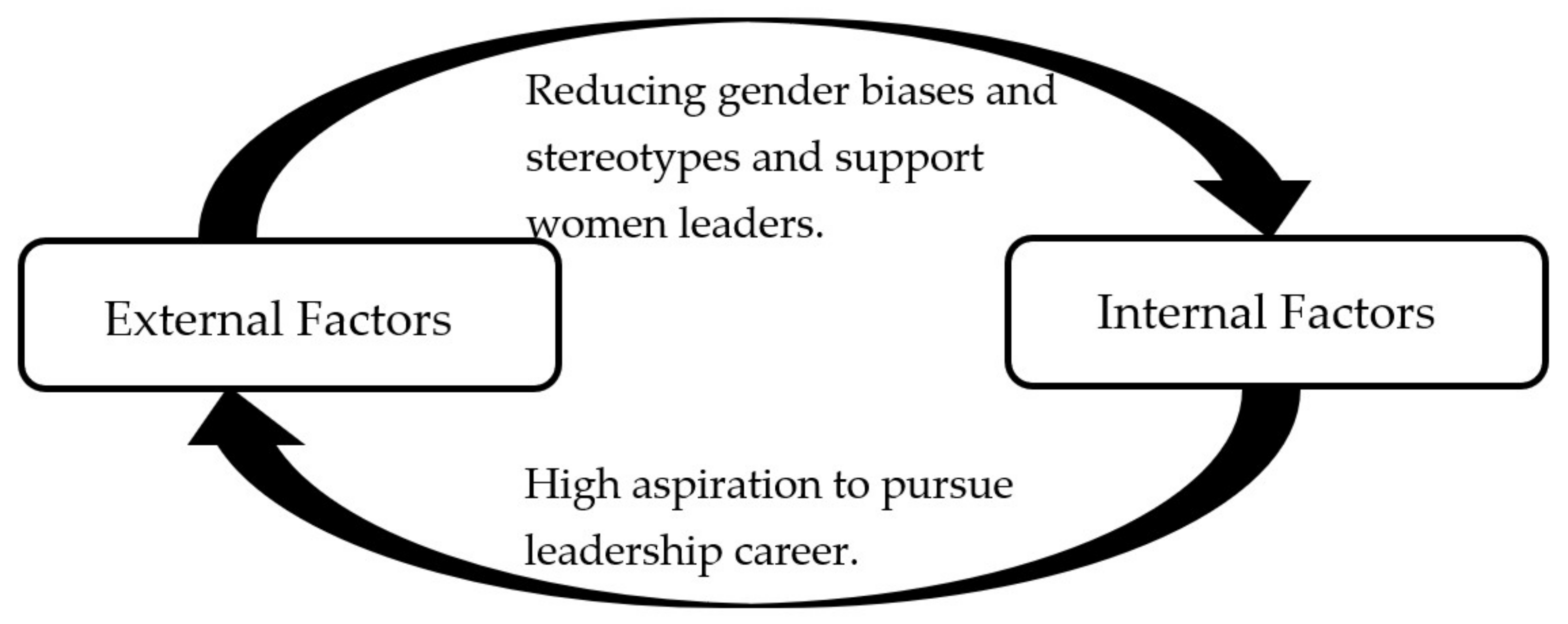

4. Organizational Practices That Promote Women’s Leadership Careers

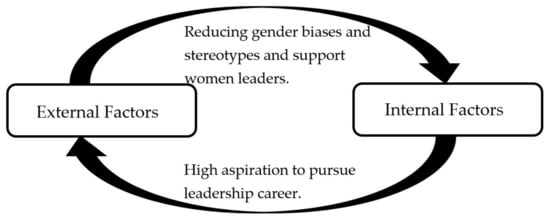

Organizations must take various measures to address the gender bias and stereotypes that create various challenges that women leaders face, as well as promote gender equality and develop a supportive and inclusive environment for women [8]. In this way, organizations are encouraged to break the vicious cycles and create virtuous ones, as shown in Figure 3. We propose the following organizational policies and practices to address the external and internal factors that contribute to the challenges that female leaders face.

Figure 3.

Virtuous cycle between external and internal factors.

First, external factors such as gender bias, gender stereotypes, and other related biases must be addressed and improved in the process. Although organizations are making progress in addressing first-generation gender biases, second-generation gender biases still hinder the emergence of women leaders. Because second-generation biases begin to influence women when they enter organizations, it is necessary to redesign the hiring and selection processes and provide manuals and training for HR personnel and those involved in hiring to avoid second-generation gender biases. Moreover, organizations should implement fair and objective criteria in employee assessments, which reduces the influence of gender biases and stereotypes in the evaluation of women. Moreover, because women often do not realize that they are affected by second-generation gender biases, offering training and lectures to raise awareness of second-generation gender biases is effective not only for men but also for women who are already working and to emphasize the importance of recognizing such biases for their career growth [20].

Second, organizations should increase the number of female leaders in top management positions because doing so would increase the proportion of female employees and leaders in organizations [93,94,95,96,97]. Research has shown that having two or more female directors or having women occupy 20% or more of the board of directors effectively reduces gender segregation within organizations [98,99]. Further, having more than three female directors normalizes the presence of women, enables them to speak freely, and fosters a more open-minded environment compared to having just one or two female directors [100]. Research has also shown that as the proportion of female leaders in an organization increases, women are more likely to speak up and exhibit greater openness than their male counterparts [100].

Third, organizations should instill confidence in women through self-development and skill-building to counter internalized gender stereotypes, thereby increasing their self-esteem. When women who aspire to be leaders do not experience gender biases and possess high self-esteem, they can create a virtuous cycle by influencing the external factors that they encounter, such as gender bias and stereotypes. To achieve this, and given the fact that women receive fewer leadership development opportunities, organizations should intentionally provide women with opportunities to learn leadership, gain leadership experience, and connect with leaders, just as men are. Organizations should also assign female mentors who are successful leaders and can serve as role models for women. Giving women more opportunities to build personal networks within and around organizations can also be an effective means to develop their leadership skills [33].

Fourth, organizations should support female leaders in their choice of appropriate leadership styles. Many studies have suggested that the transformational leadership style and servant leadership style are well-suited for women [42,48]. However, due to the second-generation gender bias that women leaders face, they may be inclined to adopt leadership styles that conform to gender stereotypes [80]. Nonetheless, it is important to adopt leadership styles that showcase their abilities as leaders, in addition to their status as female leaders. Therefore, organizations should not only support female leaders in finding leadership styles that suit their strengths but also provide a free and inclusive environment in which individuals can thrive. This approach recognizes and evaluates the unique strengths and abilities of women as leaders without conforming to traditional gender norms, reducing the likelihood of the glass cliff phenomenon. Creating an environment in which organizations recognize and accept female leaders as true leaders contributes to breaking free from gender consciousness and addressing the internal factors such as self-gender stereotypes. Therefore, it is important for organizations to establish training programs to enhance women leaders’ self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-efficacy, which may be negatively affected by not having access to various learning opportunities and experiences due to being a minority in the organization.

5. Future Directions

Given the vast amount of literature on women’s leadership, and due to space limitations, our literature review focuses on organizations generally in Europe and the United States, without being specific to a particular country or region. Therefore, the list is not exhaustive enough to cover every type of challenge that women experience in their leadership careers. Although we mainly focus on the challenges that stem from gender bias and stereotypes, many other challenges could be integrated into the model proposed in this integrative review.

First, it is important to acknowledge the influence of diverse social backgrounds due to cross-cultural differences. According to the research findings, gender issues vary from country to country and region to region [101]. For example, in cultures with high masculinity, masculine leadership traits may be emphasized, whereas in cultures with high femininity, feminine leadership traits may be more valued. Moreover, countries with a masculine culture tend to have a prevalent perception of male leadership, whereas female leadership may be less recognized. Alternatively, countries with a feminine culture tend to show less disparity in leadership styles between men and women, and female leadership may be more acknowledged [102]. Enkhzul [103] has also revealed that companies operating in countries with a culture that frequently highlights male achievements are likely to create a corporate culture that aligns with the cultural norms of the host country when expanding into countries where female achievements are more prominent [103,104]. Therefore, it can be argued that female leadership outcomes can vary across countries and cultures, and it is possible to incorporate models that integrate career paths of female leaders in countries with high femininity cultures.

Second, the gender biases and stereotypes that are prevalent in wider society should also be considered. For example, although both men and women can be plagued by work–family issues, women are more likely to be affected by heavy family responsibilities than their male counterparts in most societies because of the gender stereotype that women should take more care of family issues than men. Indeed, work–family issues are frequently studied in the context of women’s leadership [31,105,106]. Therefore, the challenges related to work–family issues faced by female leaders need to be further examined and used to enrich the integrative model.

Third, future work could incorporate negotiation issues into the integrative model on women’s leadership challenges [107]. Research on gender and negotiations has indicated that descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotypes, such as those discussed earlier in this review, influence how men and women negotiate [107], which may also influence how women leaders negotiate and differ from male leaders. Focusing on gender differences in leadership communication styles may also be an interesting avenue for future research on women’s leadership challenges. In the context of entrepreneurial financing, Huang, Joshi, Wakslak, and Wu [108] found that female entrepreneurs tend to use concrete language that is perceived as short-term oriented when describing their ventures, whereas male entrepreneurs tend to speak in abstract terms that are perceived as long-term oriented. A similar tendency may be observed in leaders’ communication toward followers in organizations.

Finally, future research should also deepen our understanding of the interplay of the external and internal factors that contribute to the challenges that women leaders experience in their organizational careers. It is particularly significant to theoretically and empirically investigate whether the vicious circle between external and internal factors can be transformed into a virtuous circle that promotes women’s leadership in organizations.

6. Conclusions

In recent years, with the promotion of gender equality, the topic of female leadership has received a great deal of attention, and calls for change and reform to transform gender issues within organizations are increasing. Nonetheless, conscious and unconscious gender biases that discriminate against women within organizations still exist. Identifying unconscious gender bias is especially difficult, but it is the foundation for perpetuating gender discrimination. Although attention is often focused on gender issues within organizations to increase the number of female leaders, little attention is paid to the gender stereotypes that women may internalize and hold.

Gender bias and stereotypes can harm women, causing them to doubt their skills and abilities and potentially limiting their opportunities to lead or take on challenging projects in the workplace. A lack of confidence can restrict women’s career opportunities and hinder their professional growth, as well as perpetuate male-dominated leadership positions and maintain gender inequality. Therefore, it is critical to have a comprehensive understanding of the challenges affecting women’s leadership careers, and organizations must implement policies and practices to support women based on such an understanding. Moreover, women leaders must not only resist external gender challenges caused by gender bias and stereotypes but also believe in themselves, including their gender identity, and actively strive for leadership positions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. and T.S.; investigation, E.G. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G. and T.S.; writing—review and editing, E.G. and T.S.; supervision, E.G. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cook, A.; Glass, C. Between a rock and a hard place: Managing diversity in a shareholder society. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2009, 19, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Richard, O.C.; Triana, M.C.; Zhang, X. The performance impact of gender diversity in the top management team and board of directors: A multiteam systems approach. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Glass, C. Women and top leadership positions: Towards an institutional analysis. Gend. Work. Organ. 2014, 21, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Glass, C. Leadership change and shareholder value: How markets react to the appointments of women. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C. The leadership styles of women and men. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, R.J.; Ibarra, H.; Kolb, D.M. Taking gender into account: Theory and design for women’s leadership development programs. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 1990, 4, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L. Gender, status, and leadership. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M. New solutions to the same old glass ceiling. Women Manag. Rev. 1992, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, F.; Heilman, M.E. Breaking the glass ceiling: For one and all? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 120, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiguchi, T.; De Cuyper, N. Addressing new leadership challenges in a rapidly changing world. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.L. The glass escalator: Hidden advantages for men in the “female” professions. Soc. Probl. 1992, 39, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmüller, S.; Ryan, M.K.; Rink, F.; Haslam, S.A. Beyond the glass ceiling: The glass cliff and its lessons for organizational policy. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2014, 8, 202–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, C.C.; Swim, J.K.; Jacobs, R.R. Evaluating gender biases on actual job performance of real people: A meta-analysis 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 2194–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, C.; Rodríguez, J.; González, M.J. Mind the job: The role of occupational characteristics in explaining gender discrimination. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 156, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Huang, L. Gender bias, social impact framing, and evaluation of entrepreneurial ventures. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batara, M.A.; Ngo, J.M.; See, K.A.; Erasga, D. Second generation gender bias: The effects of the invisible bias among mid-level women managers. Asia-Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2018, 18, 138–151. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332154630 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Fischbach, A.; Lichtenthaler, P.W.; Horstmann, N. Leadership and Gender Stereotyping of Emotions. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Hersby, M.D.; Bongiorno, R. Think crisis–think female: The glass cliff and contextual variation in the think manager–think male stereotype. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, A.M.; Eagly, A.H.; Mitchell, A.A.; Ristikari, T. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddy, P.W.; Sturm, R.E.; Atwater, L.; Taylor, S.N.; McKee, R.A. Gender bias still plagues the workplace: Looking at derailment risk and performance with self–other ratings. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, 45, 315–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L.; Correll, S.J. Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gend. Soc. 2004, 18, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, H.-J.; Gratton, L. Gender role self-concept, categorical gender, and transactional-transformational leadership: Implications for perceived workgroup performance. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E. Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E.; Wallen, A.S.; Fuchs, D.; Tamkins, M.M. Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E.; Okimoto, T.G. Why are women penalized for success at male tasks?: The implied communality deficit. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correll, S.J. Constraints into preferences: Gender, status, and emerging career aspirations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2004, 69, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, G.F. Breaking the glass ceiling: The effects of sex ratios and work-life programs on female leadership at the top. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, R.J.E.; Herminia, K.; Deborah, M. Women rising: The unseen barriers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carli, L.L.; Eagly, A.H. Women face a labyrinth: An examination of metaphors for women leaders. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 31, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex differences in social behavior: Comparing social role theory and evolutionary psychology. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1380–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Few Women at the Top: How Role Incongruity Produces Prejudice and the Glass Ceiling. In Leadership and Power: Identity, Leadership, and Power; van Knippenberg, D., Hogg, M.A., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Schock, A.K.; Gruber, F.M.; Scherndl, T.; Ortner, T.M. Tempering agency with communion increases women’s leadership emergence in all-women groups: Evidence for role congruity theory in a field setting. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]