1. Introduction

Calcium (Ca) is the most abundant soluble cation in the Earth’s crust [

1,

2] and is classified as an essential secondary macronutrient that performs crucial functions in plant physiology [

3]. At the cellular level, Ca not only maintains membrane integrity and the physicochemical stability of proteins [

4] but also constitutes a fundamental structural component of the cell wall [

5]. Its uptake occurs primarily through the roots [

6]; however, its limited phloem mobility restricts transport to growing tissues and accumulation in fruits [

7]. In tomato, this limitation leads to physiological disorders such as blossom-end rot [

8] and apical necrosis [

9,

10], requiring a continuous supply during the critical fruit development stage [

11,

12].

Additionally, Ca regulates key processes including root development, cell elongation and division [

13,

14,

15], microbial activity, and molybdenum (Mo) availability [

8]. The bioavailability of Ca is closely linked to its exchangeable levels in the soil, which reflect its release from minerals such as calcite and gypsum [

16,

17]. Moreover, the balance with other cations (Mg and K) is critical for optimal absorption [

18]. While Ca supplementation has been shown to improve yield under soil-deficiency conditions [

19,

20], agronomic diagnostic criteria classify concentrations above 5000 ppm as excessive [

21]. This generates a critical research gap: in soils that are naturally rich in Ca (4886 ppm) and alkaline (pH of 8.04), it remains unclear whether yield is limited by the bioavailability of native Ca or by ionic competition, which complicates efficient management.

Historically, low Ca uptake efficiency has been addressed through excessive fertilizer applications [

22]. However, since these practices are unsustainable and contribute to soil degradation, integrating fertigation with organic amendments has been promoted as a viable alternative [

23,

24,

25]. Organic amendments (e.g., poultry manure compost) have been shown to improve the chemical, physical, and biological properties of soils, enhancing nutrient absorption, microbial activity, and water retention [

26,

27,

28]. Despite these benefits, their validation in soils with high Ca concentrations requires further investigation.

In recent years, research has highlighted that tomato genotypes may respond differently to Ca availability, indicating the importance of genotype-specific studies in nutrient management. Genetic variation in Ca uptake, transport, and allocation can influence both fruit quality and susceptibility to physiological disorders [

29]. Understanding these genotype-specific responses is essential for designing targeted fertilization strategies and optimizing productivity under variable soil conditions.

Furthermore, the interaction between soil Ca, organic amendments, and microbial communities represents a promising avenue for enhancing crop resilience. Organic amendments can stimulate beneficial microbial populations that facilitate nutrient cycling, improve soil structure, and promote water retention, potentially mitigating the limitations of native Ca availability [

30,

31]. Integrating these management practices may contribute to more sustainable and efficient tomato production, particularly in alkaline soils with naturally high Ca content.

In this context, the present study evaluated Ca availability and the effect of organic amendments on tomato production. It was hypothesized that Ca availability in alkaline soils may differ between native and supplemented sources and can be modified by organic amendments. Therefore, the study aimed to determine whether native Ca meets crop requirements and how management practices induce variations in yield and quality, with genotype-specific responses. This dual design allowed exploration not only of the role of soil Ca in crop nutrition but also of the potential of amendments to promote microbial activity, improve water retention, and enhance fruit productivity and quality [

29,

30].

2. Materials and Methods

This section includes a description of the materials used, the experimental design, the management procedures, and the analytical techniques applied. It details the environment in which the experiment was conducted, the treatments applied, and the specific methodologies for data collection and analysis.

Both experiments were conducted at the same experimental site to ensure comparable soil conditions and to establish a direct relationship between them. Prior to experiment establishment, soil chemical properties were characterized (

Supplementary Material), revealing low organic matter content (1.54%) and very high calcium availability (4886 ppm), which supported the experimental focus on calcium management and organic matter amendments.

2.1. Location of the Experimental Site

This research was conducted at the Valerio Trujano nursery of the Superior Agricultural College of the State of Guerrero, located in the municipality of Tepecoacuilco de Trujano 11 km from the Iguala–Huitzuco highway, at an altitude of 860 m above sea level (17°54′ N, 99°41′ W). The experimental site is characterized by a loam–clay–sand soil containing 4886 ppm of Ca, with a pH of 8.04, an electrical conductivity of 0.51 dS m−1, and a bulk density of 1.3 g cm−3. Although total Ca content is high, the low electrical conductivity indicates reduced concentrations of soluble Ca in the soil solution. This condition is associated with the alkaline pH and the soil texture, which limit Ca solubilization and promote its binding to carbonates and clay surfaces. Consequently, the actual availability of Ca to plants depends primarily on its release into the soil solution rather than on the total Ca present in the soil matrix.

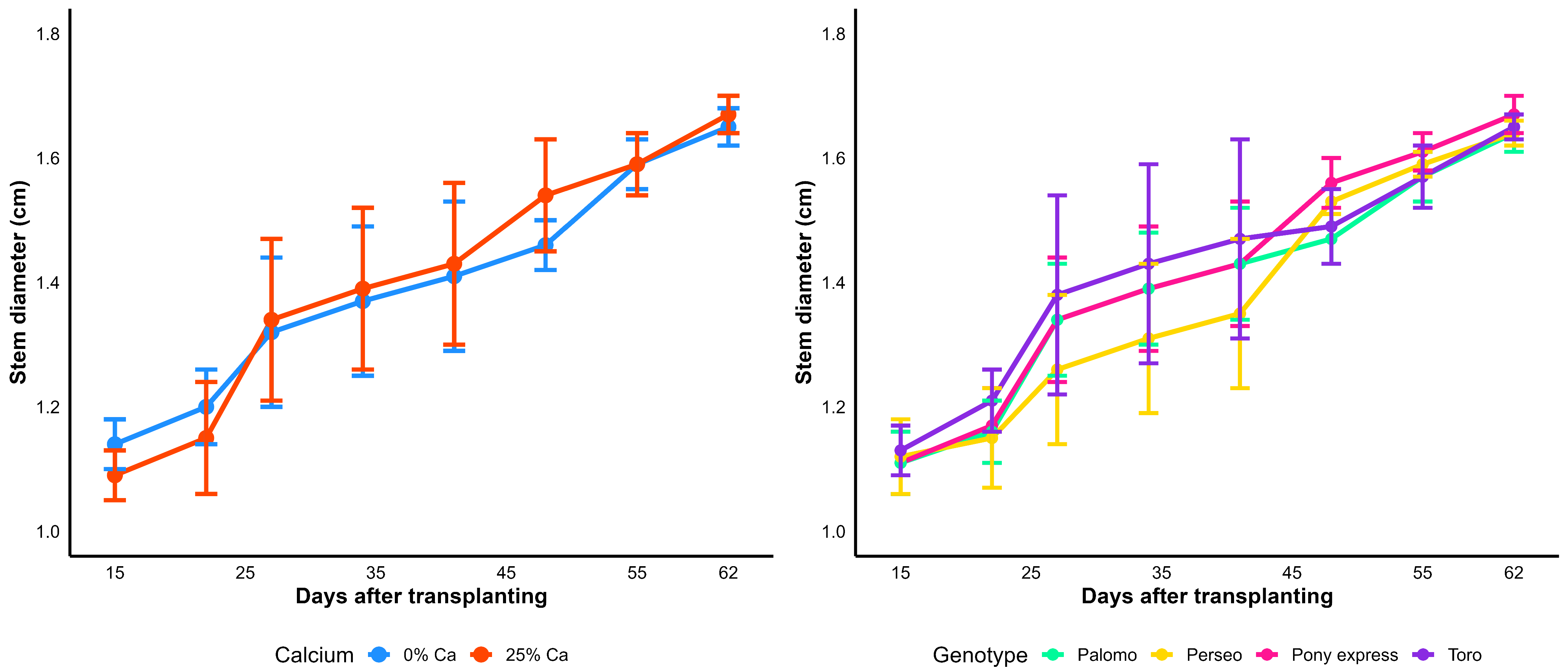

In the first cycle, carried out under 50% shade-house conditions, four tomato genotypes (Toro, Pony express, Perseo, and Palomo) were evaluated under two Ca application levels (0% and 25%). In the second cycle, established under open-field conditions, organic amendments were incorporated as an additional factor, complementing the fertigation strategy applied during the first cycle, as implemented by [

32].

The shaded house where the crop was established is a structure covered with 50% shade mesh, measuring 16 m in width by 24 m in length, with iron supports spaced 4 m apart. It regulates the climatic environment and protects the crop from adverse conditions such as intense solar radiation, strong winds, and pest attacks. The maximum temperature inside the shaded house was 29.1 °C during the day and 24.7 °C at night, with an average of 26.9 °C, with an average relative humidity (RH) of 78.5% during the day and 86.5% at night.

2.2. Genetic Material

The genotypes used in this study are described below, all from the commercial brand Harris Moran. These materials were selected because they were the ones available at the time the research was conducted; therefore, their selection was not random.

Pony express, Palomo, Toro, and Perseo are determinate tomato genotypes characterized by high fruit quality, good firmness, intense red color, and high yield. Pony express exhibits early maturity and concentrated productivity; Palomo stands out for its vigor, extended shelf life, and maximum production; Toro is notable for its firmness and suitability for long-distance transport; and Perseo produces large, uniform, and high-quality fruits [

33,

34,

35,

36].

2.3. Factors and Treatments Under Study

Two factors were evaluated over two consecutive years. In the first year, calcium (Ca) was studied at two levels (0% and 25%) in combination with four tomato genotypes. In the second year, the experimental factor was the application of soil amendment, evaluated at two levels (with and without), also in combination with the same four genotypes, all from the commercial brand Harris Moran (see

Table 1).

2.4. Experimental Design and Experimental Unit

The experimental design used was a split-plot design, where the large plots represented the Ca levels, and the small plots were randomized with the tomato genotypes. The experimental unit consisted of two planting beds, each 1.20 m wide and 4 m long, resulting in an area of 4.80 m2. Four replications were performed for each treatment, resulting in a total of 32 experimental units. Each large plot had an area of 192 m2, where ten cultivation beds were established. The first and last beds were used as borders, and the remaining eight beds were used for the establishment of the genotypes (two planting beds per genotype). The plant spacing was 0.40 m, with twenty plants per experimental unit arranged in double rows. Two plants were discarded from each row, one at each end, resulting in a useful plot of sixteen plants per experimental unit. Four plants were measured for growth and sixteen for yield.

2.5. Seedling Production

For the planting process, a substrate mixture of peat moss and lama soil was used. The peat moss was sifted through a mesh sieve and then combined with the lama soil at a 1:3 ratio, meaning for every part of peat moss, three parts of lama soil were added. The lama soil was sterilized with Anibac at a concentration of 5 mL L−1. In a 200 L container, a solution of water and Anibac was prepared at a dose of 5 mL L−1 of water, and polypropylene trays with 200 cavities were disinfected by immersing them for 5 min. Meanwhile, the substrate was thoroughly moistened using a backpack sprayer, and the trays were then filled. The planting took place on 26 October 2018, with one seed placed per cavity at a depth of 0.5 cm. Following this, a light irrigation was applied using the fungicide Captan Ultra 500 WP (Captan) at a concentration of 1.5 g L−1 of water. Upon completion of this step, the trays were stacked and covered with polyethylene until the emergence of the seedlings (within three days). The trays were then transferred to a nursery, where they remained for 28 days to protect them from vector attacks that transmit viral diseases. During the seedling stage, irrigations were carried out twice daily (morning and afternoon) with a solution of Rootex (rooting hormone) at a dose of 2 g L−1 of water and Captan at a concentration of 1.5 g L−1 of water using a backpack sprayer to prevent diseases. Fertilization of the tomato seedlings was applied alternately (every third day) with a solution of the water-soluble fertilizer Ultrasol Inicial (15-30-15) at a dose of 1.5 g L−1 of water and the foliar fertilizer Bio-Green Plus (20-30-10) on three occasions (once a week) at a dose of 5 g L−1 of water.

2.6. Land Preparation and Irrigation System Installation

The land was manually cleared with the help of a hoe, and subsequently, the planting beds were made. These were created manually, with a distance of 120 cm between furrows. Ten beds were made for the treatments with Ca, and another ten beds were made for the treatments without Ca. Once the beds were completed, mulch was applied. For the installation of the drip irrigation system, 6.35 cm PVC tubing was used for the main network, and 5.08 cm hoses were used for the secondary network. In the tertiary network, 2.54 cm hoses were connected, where individual spider-type drippers with 4 outlets and a flow rate of 2 L h−1 were placed every 60 cm. Additionally, a 5.08 cm mesh filter header was installed for the application of the nutrient solution, along with a 3 HP capacity pump.

2.7. Transplanting

The transplanting was carried out on 20 November 2018, for which a pointed stick was used to create planting cavities of a size similar to the root ball of the plants. Before transplanting, a solution of Rootex at 3 g L−1, Proplant at 3 mL L−1, Aminocel 500 at 3 g L−1, and Interguzan at 3 mL L−1 was applied. The seedlings were removed from the tray with the entire root ball and placed one plant per cavity, ensuring that the plant’s collar was level with the soil surface. A light soil compaction was applied around the plant without damaging the stem, to avoid air pockets and ensure a 100% success rate for the transplant.

2.8. Fertirrigation

The nutrient solution irrigation was applied every eight days, with fertilizers such as calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca (NO

3)

2·4H

2O), magnesium sulfate (MgSO

4·7H

2O), monopotassium phosphate (KH

2PO

4), potassium nitrate (KNO

3), and ammonium sulfate ((NH

4)

2SO

4) being applied according to the plant’s growth stage (

Table 2). The total amount of Ca supplied during the crop cycle was 29 kg, corresponding to 25% of the plant’s total Ca requirement. This reduced level was intentionally selected to evaluate whether a minimal supplemental application could enhance crop performance under conditions where the actual availability of native soil calcium may have been limited due to the physicochemical characteristics of the alkaline soil. Once the required amount of fertilizer was calculated, the pH of the water was reduced to 5.5, and the fertilizer was weighed, dissolved in a 20 L capacity container, and then transferred to the corresponding container with a capacity of 1100 L.

The application of irrigation without the nutritive solution of Ca (

Table 3) was also applied every eight days. The fertilizers used were the same, except for the calcium nitrate tetrahydrate.

2.9. Foliar Fertilization During the Crop Cycle

High Ca concentration and alkaline soil pH can reduce the availability and uptake of essential micronutrients such as Mg, K, boron (B), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn), due to antagonistic interactions and low solubility under elevated-pH conditions. For this reason, micronutrient fertilization was supplemented during the cultivation period (

Table 4).

2.10. Compost Preparation

Compost was produced using layer hen manure of approximately four weeks old, combined with sawdust bedding (chicken litter), totaling about one ton. The chicken litter was spread and moistened to field capacity, ensuring uniform hydration through manual turning with a shovel. The pile was covered with black plastic to retain moisture and heat. To control temperature, the compost was turned twice daily. When high temperatures persisted, an equal volume of compost made from leaves and bovine manure was added to balance the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N) and mitigate overheating. The composting process lasted 41 days.

The compost exhibited a C/N ratio of 13:1, a pH of 6.8, and an electrical conductivity of 4.5 dS m−1, values that indicated a stabilized material, slightly alkaline in nature, with a moderate concentration of soluble salts.

Incorporation of the Amendment

The planting beds were constructed manually, with dimensions equivalent to those mentioned in

Section 2.4. The compost was incorporated manually by opening furrows approximately 15 cm deep along the planting beds and evenly distributing the compost together with the fertilizers, potassium nitrate (KNO

3) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO

4), at rates of 9.6 kg, 1.10 g, and 2.60 g per linear meter, respectively. Once the amendment was incorporated, the furrows were covered and the planting beds were reconstructed.

Additional fertilization was applied via fertigation, following the same criteria used in the previous cycle (

Table 2 and

Table 4) for the amendment factor.

The beds were mulched with black/silver polyethylene to suppress weed growth and enhance moisture retention. The mulch was perforated in double rows with 40 cm spacing between holes to allow for crop transplanting.

2.11. Harvest

The first crop cycle lasted 174 days, from 26 October 2018 to 17 April 2019. The first harvest was carried out 100 days after transplanting (dat), with a harvesting period of 39 days. In the second cycle, the harvest was conducted on 30 March 2020, at 78 dat.

2.12. Response Variables

At each harvest, the fruits from each treatment and repetition (Rep) were classified according to their quality: first quality (100 g), second quality (50–100 g), third quality (20–30 g), fourth quality (20 g), and waste (<20 g or damaged). Once the crop was established, the following phenological variables were measured:

Plant height: Determined by measuring with a tape measure from the soil to the apex of the plant.

Neck diameter of the plant: Determined with a digital caliper by measuring the plant’s neck.

Average fruit weight: Measured by averaging the weights of the first- and second-quality fruits.

Fruit diameter: Determined only for first-quality fruits.

Fruit length: Measured with a digital caliper for first- and second-quality fruits.

Number of fruits per square meter: Determined by separating the heavier fruits and counting them by treatment for first-quality, second-quality, third-quality, fourth-quality, commercial, and total fruits.

Fruit weight per square meter: Determined by weighing the first-quality, second-quality, third-quality, and total fruits.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of the evaluated variables was performed using SAS software version 9.4 and R version 4.5 [

37]. For the variables that showed a significant genotype effect, means were compared using Tukey’s test.

Because the treatments applied in year 1 (shade house) and year 2 (open field) correspond to different management packages (year 1: Ca application levels via fertigation; year 2: an organic amendment based on poultry manure supplemented with K and Mg), the whole-plot factor does not represent equivalent interventions across years. To maintain consistency in the split-plot design structure and to avoid confounding treatment effects with year-specific environmental differences, statistical analyses were conducted separately for each cycle using the same base model.

The statistical model used in both years was

In this model, represents the observed value of the response variable at the i-th level of the main factor, the j-th genotype, and the k-th replication. The term denotes the overall mean. The factor describes the effect of the whole-plot management treatment, which in year 1 corresponded to the two Ca application levels (0% and 25%) and in year 2 to the two soil amendment levels (no amendment vs. amendment). The term represents the effect of the k-th replication, while is the whole-plot error term. The subplot factor corresponds to the genotype effect, which remained the same in both years. The interaction term captures the differential response of genotypes to the main factor within each year, and represents the residual error term.

This approach maintains methodological consistency while ensuring that the results from each year are interpreted within their specific agronomic context.

Percentage Calculation

Relative variations between treatments were expressed as percentages with respect to the control. The calculation was performed using the following formula:

where

corresponds to the observed value in the treatment and

to the observed value in the control.

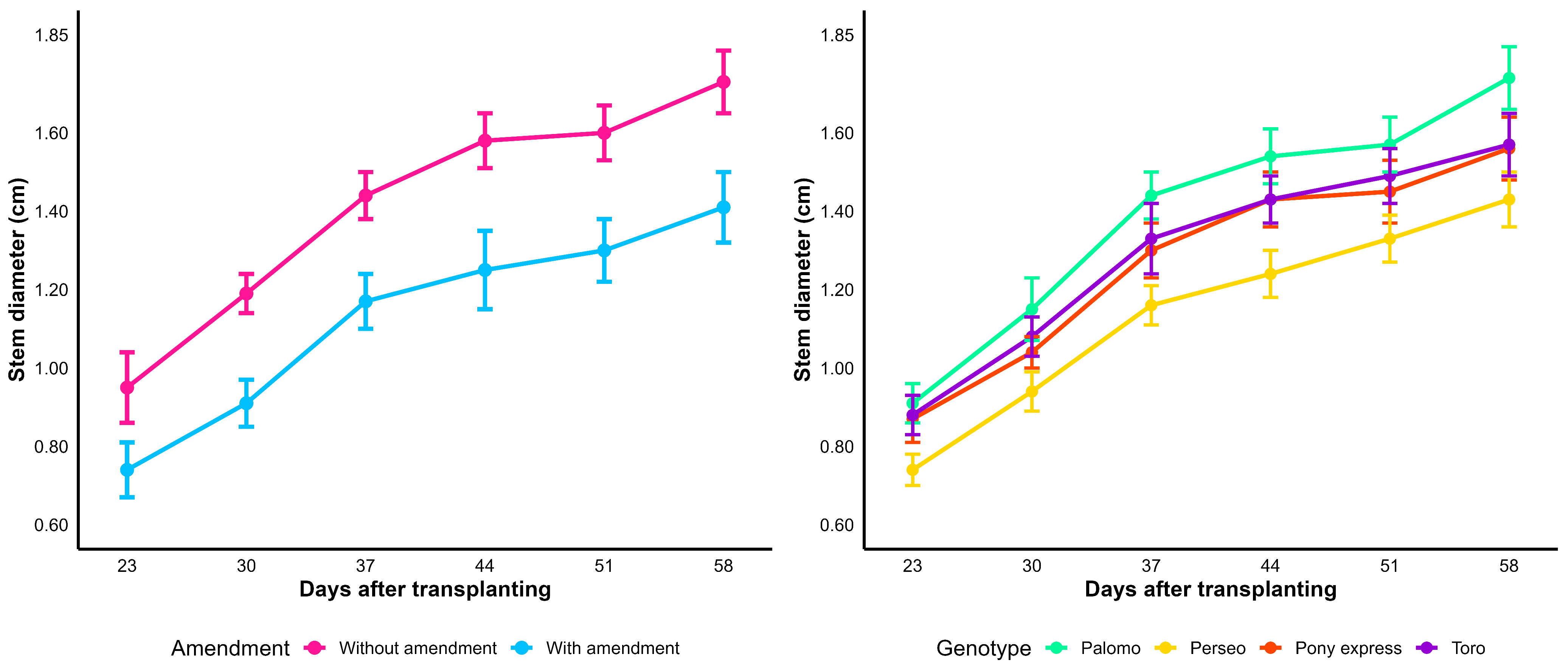

4. Results: Year 2

In the previous experimental cycle, conducted under shade house conditions, two calcium application levels (0% and 25%) were evaluated. The results showed that the 0% calcium treatment exhibited better performance in yield-related variables, indicating that the crops did not show calcium deficiency under these conditions. Consequently, the natural availability of calcium in the soil was sufficient to meet the crops’ demand, allowing for higher yield compared with the 25% level. Considering these findings, in the second cycle the 0% calcium level was maintained as a reference, but a new management factor (the application of a soil amendment) was introduced, and the experiment was moved to open-field conditions, providing a scenario more representative of actual commercial production conditions.

4.1. Plant Height

The analysis of variance revealed that the application of organic amendment had a significant effect on tomato plant height across all sampling dates, from 23 to 58 dat, with significant differences observed from 37 dat onward (

Table 12). On average, plants grown with amendment reached greater height values, attaining 0.85 m at 58 dat, compared to 0.71 m in the treatment without amendment. Regarding the genotype factor, significant differences were observed between 23 and 44 dat, as well as at 58 dat. The genotype Perseo exhibited the greatest height values during the early stages (23–44 dat), whereas Palomo reached the highest final height, with 0.84 m at 58 dat. In contrast, Pony express and Toro showed intermediate growth patterns.

A visual representation of

Table 12 is shown in

Figure 5, where the genotype factor illustrates how the genotype Perseo stabilized its growth.

The standard deviations of plant height remained stable across all treatments (

Figure 5), indicating minimal within-group variability and a highly uniform growth pattern among plants of the same genotype and amendment level. Similarly, stem diameter exhibited consistently low standard deviations (

Figure 6), confirming the stability of this trait throughout the experiment. The error bars show a reduced dispersion around the means, suggesting that the observed differences among genotypes and amendment levels were primarily attributable to treatment effects rather than internal variability within groups.

4.2. Neck Diameter of the Plant

Table 13 presents the values of stem collar diameter recorded throughout the evaluations after transplanting. Significant differences were observed for both factors at all assessment dates. The values under the amendment treatment exceeded those of the non-amendment treatment by 18.51% at 58 days after transplanting (dat). Regarding the genotype factor, the hybrid Palomo exhibited the largest stem collar diameter, whereas Perseo showed the lowest values, reflecting the genetic variability in this trait.

In the graph for the amendment factor (

Figure 6), a progressive increase is observed over time at both amendment levels. Although the trajectories are close, the figure clearly shows differences between treatments at all sampling times, consistent with the significant differences reported in

Table 13.

Regarding the genotype factor, the evaluated materials exhibited a similar growth pattern in stem diameter during most of the observation period. However, the graph reveals visible differences among genotypes at specific time points, confirming the presence of significant effects at particular stages of development.

4.3. Average Fruit Weight

The incorporation of organic amendment did not produce significant differences in the weight of first- or second-quality fruits (

Table 14). In contrast, the genotype factor showed significant differences in the weight of first-quality fruits. The genotype Perseo recorded the highest value, with an average fruit weight of 160 g, while the other genotypes exhibited lower values. For second-quality fruits, all genotypes showed statistically similar performance.

4.4. Fruit Diameter

The analysis of variance (

Table 15) indicates that the incorporation of organic amendment did not produce significant differences in fruit diameter, suggesting that this variable was not directly influenced by the amendment under the field conditions of the second growing cycle. Regarding the genotype factor, significant differences were observed in the diameter of second-quality fruits, with the genotypes Palomo and Toro standing out by reaching the highest value, both at 4.92 cm. For first-quality fruits, all genotypes behaved statistically similarly, showing a more homogeneous range for this variable.

Furthermore, when examining variability among genotypes, Palomo and Toro consistently exhibited the highest values for second-quality fruits, while the remaining genotypes maintained intermediate diameters.

4.5. Fruit Length

According to

Table 16, the length of first- and second-quality fruits did not show significant differences with the incorporation of amendments, indicating that this factor did not directly affect fruit development under the evaluated field conditions.

Regarding the genotype factor, significant differences were observed in the length of first-quality fruits. The genotype Perseo achieved the greatest fruit length at 7.60 cm, whereas the other genotypes presented lower but statistically distinct values, reflecting the genetic variability of this trait.

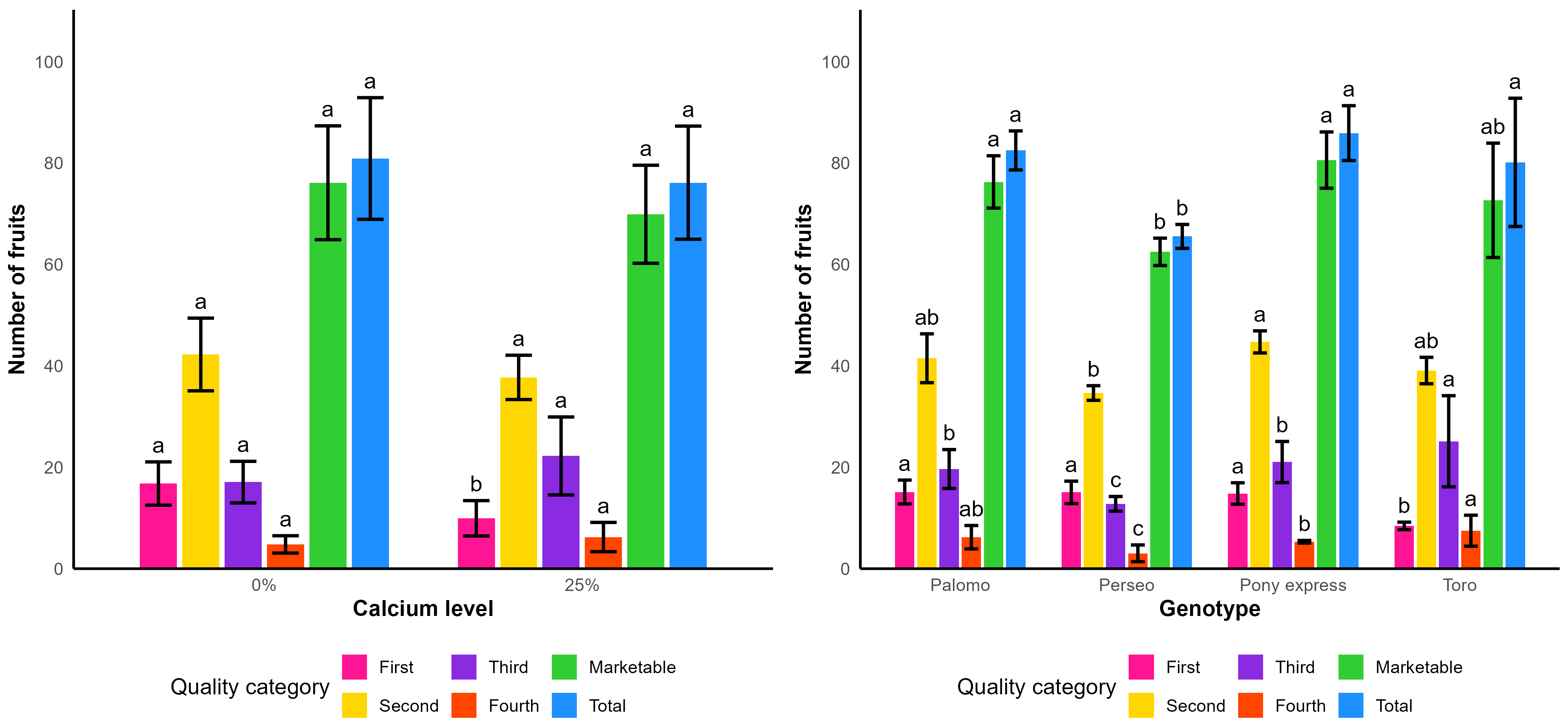

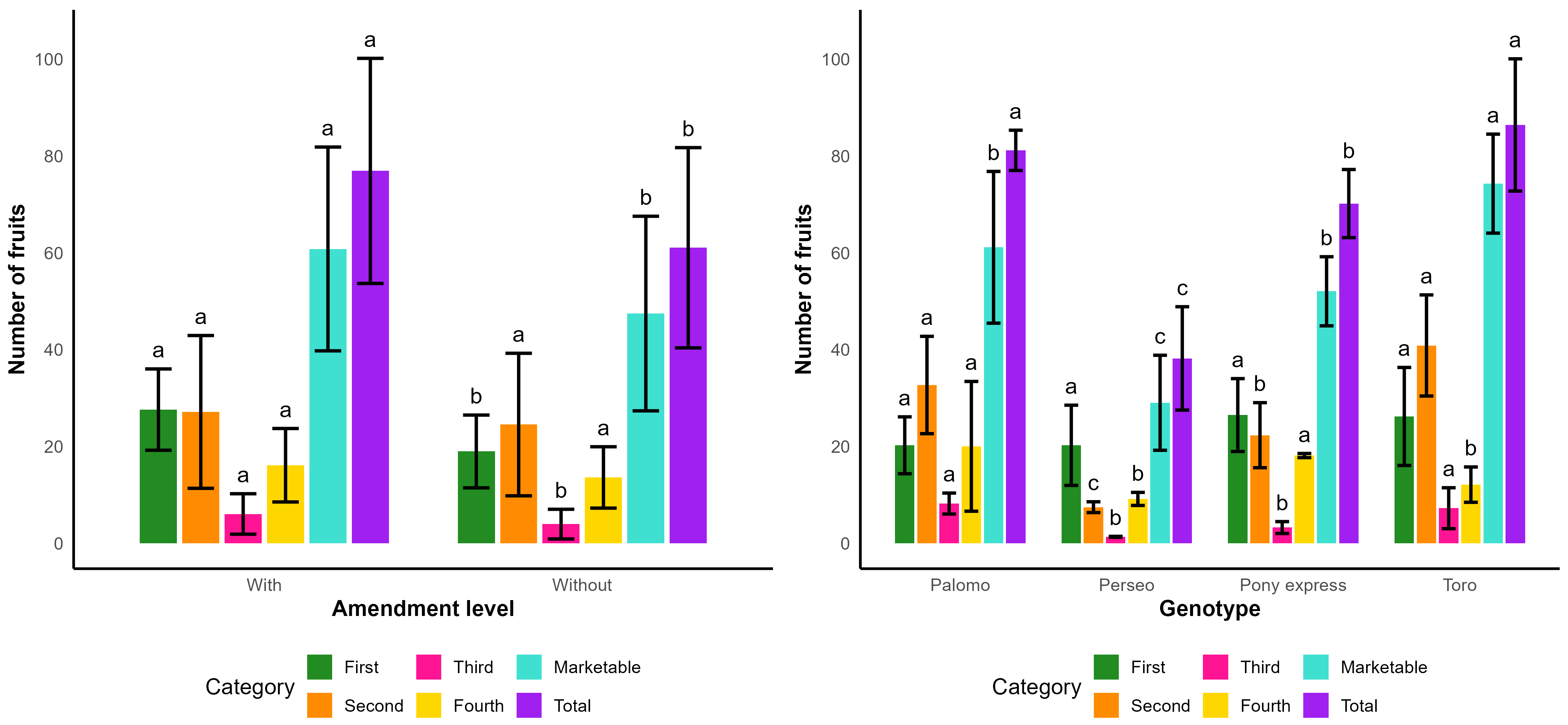

4.6. Number of Fruits per Square Meter

In

Table 17, it can be observed that, for the amendment factor, first-quality fruits showed significant differences, with the amendment treatment producing a higher number of fruits per square meter (27.63) compared to the treatment without amendment (18.98), representing an increase of 31.31%. Likewise, significant differences were detected in the number of marketable fruits per square meter, once again favoring the amendment treatment.

For the genotype factor, the analysis of variance indicated significant differences in the number of fruits per square meter for second-, third-, and fourth-quality fruits, as well as for marketable and total fruits. The genotype Toro reached the highest number of fruits per square meter with a total of 86.46 fruits, statistically similar to that of Palomo at 81.21, whereas the remaining genotypes presented lower values that were statistically different.

Figure 7 provides a comparative visualization of fruit number distribution by category. It can be observed that the application of the amendment consistently enhanced production across all fruit classes, as reflected by a higher proportion of marketable fruits and an increase in total fruits per square meter. Regarding the genotype factor, the graph clearly shows that Toro and Palomo achieved the highest values for both marketable and total fruits, whereas Perseo exhibited the lowest overall production. In contrast, Pony was positioned at an intermediate level, performing particularly well in marketable fruits.

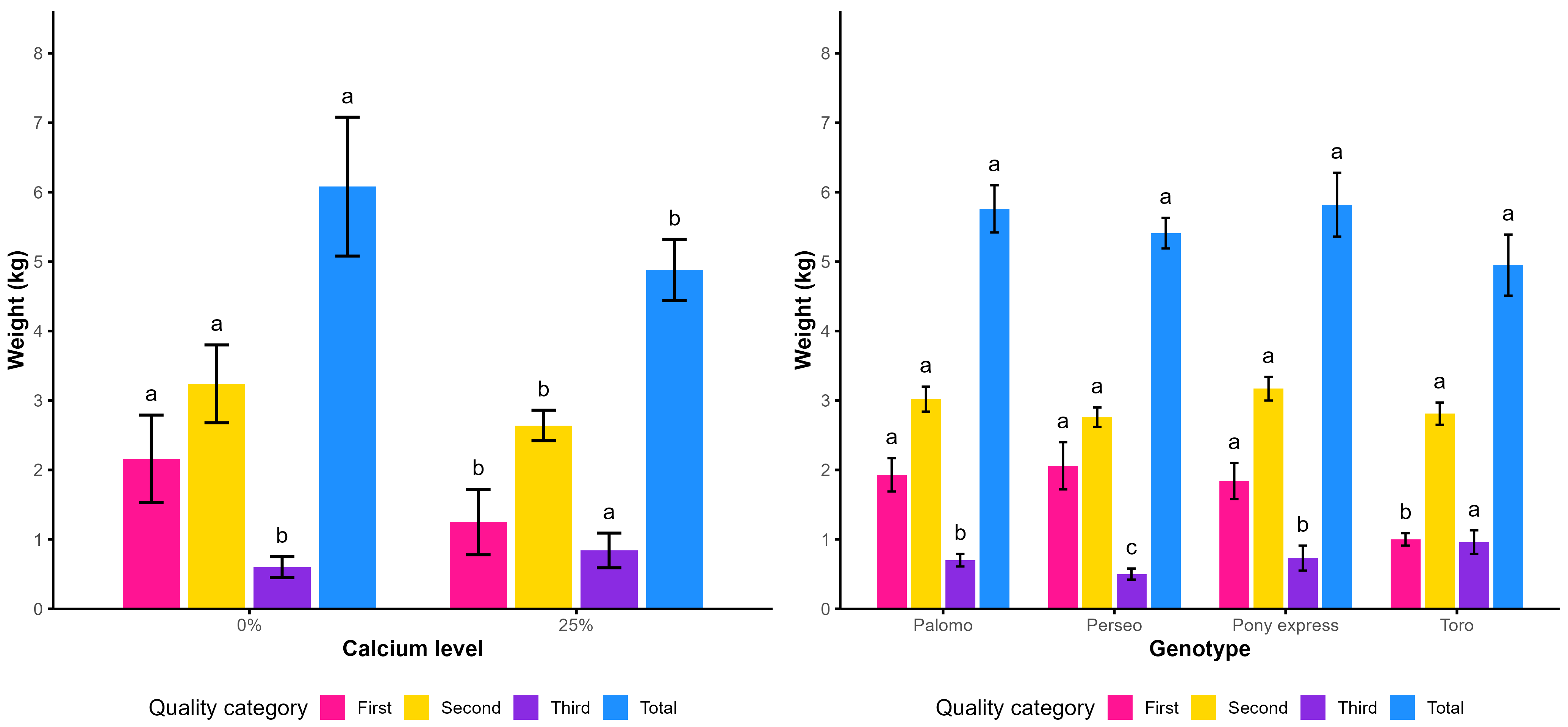

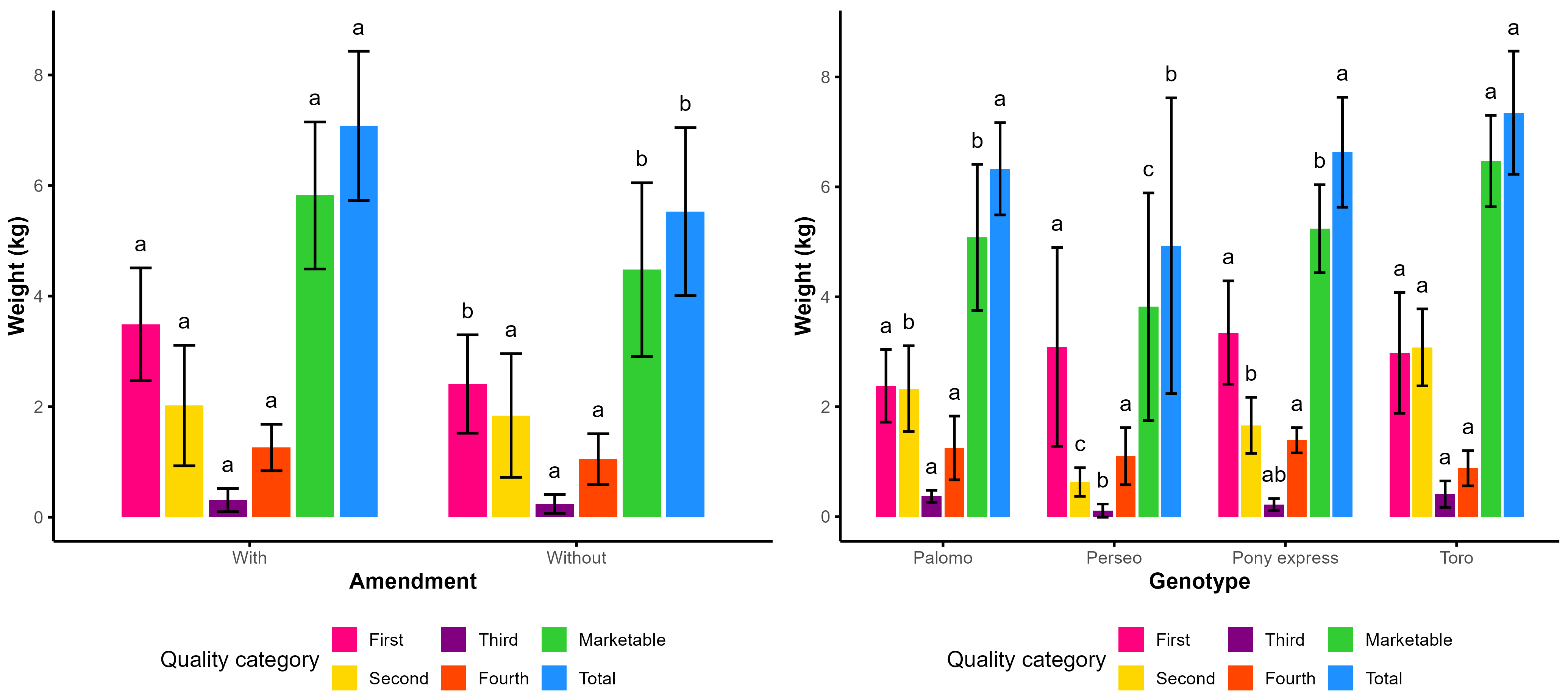

4.7. Fruit Weight per Square Meter

As shown in

Table 18, significant differences were observed regarding the amendment factor and the weight of first-quality fruits. The amendment treatment produced the highest weight, with 3.49 kg m

−2, equivalent to 34.90 t ha

−1, surpassing that of the treatment without amendment by 30.94%.

For the weight of marketable fruits per square meter, significant differences were also found. The amendment treatment achieved the highest yield, reaching 58.20 t ha−1, 23.02% higher than that of the treatment without amendment.

Regarding total fruit weight per square meter, the use of amendment produced a yield of 7.08 kg m−2 (70.80 t ha−1), while the treatments without amendment reached 55.30 t ha−1. This represents an increase of 21.89% in yield per hectare due to the application of amendment.

Concerning genotypes, significant differences were observed in fruit weight per square meter for second-, third-, and fourth-quality fruits, as well as in the weight of marketable fruits and total fruit weight. The genotype Toro was the most outstanding in total fruit weight, reaching 7.35 kg m−2, equivalent to 73.50 t ha−1.

Figure 8 shows that the application of amendments consistently increased fruit weight across all categories, with a particularly notable effect on marketable fruits. Among the genotypes, Toro reached the highest total fruit weight, followed by Palomo, whereas Perseo exhibited the lowest values, and Pony was positioned at an intermediate level.

5. Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that supplementary calcium application did not result in an improvement in tomato yield and, in certain cases, even caused a reduction. This finding is consistent with previous research emphasizing the criticality of assessing soil calcium availability prior to supplementation, in order to avoid excessive fertilizer use that could prove counterproductive. For instance, ref. [

22] reported significant calcium accumulation in greenhouse soils.

The primary explanation for the negative effect observed with the 25% calcium treatment lies in the alkaline soil pH (8.04). In soils with elevated pH, the availability of essential micronutrients such as iron, zinc, manganese, and copper is substantially reduced due to precipitation of hydroxides or the formation of insoluble complexes [

38]. The excess Ca under these conditions intensifies such processes. The improvement in first-quality fruit yield at the 0% calcium level compared to the 25% level (

Table 7 and

Table 11) is indicative of a nutritional imbalance induced by surplus Ca. Under alkaline conditions, high calcium concentrations limit the mobility and uptake of other micronutrients. As a precedent, calcareous soils with high pH have shown reduced Zn and Fe availability [

39]. Furthermore, excessive Ca has been reported to inhibit the absorption of other essential nutrients, such as potassium and magnesium [

12]. This interpretation is reinforced by the observed decrease in average fruit weight (for first and second qualities) and the consequent increase in third-quality fruit weight at the 25% treatment level (

Table 11).

The lack of effect of calcium application on fruit diameter and length (

Table 8 and

Table 9) suggests that these characteristics may be predominantly genetically determined rather than influenced by Ca availability. This aligns with [

10], who indicated that the K–Ca ratio influences fruit development through vapor pressure deficit and photosynthetically active radiation, without necessarily modifying the final fruit size or shape. Despite the foliar application of micronutrients, the high alkalinity and elevated calcium levels may have prevented a complete compensation for the restriction in edaphic availability. Management strategies for alkaline soils advise the use of chelates or acidifying amendments to enhance the availability of Fe, Zn, and Mn [

40]. In synthesis, the detrimental effects of the 25% calcium level stem from a synergistic interaction between high pH and excess Ca, which promotes micronutrient precipitation and generates deficiencies, negatively affecting plant physiology, growth, and fruit quality. Recent studies have highlighted similar mechanisms, including the role of humic and fulvic acids in the mobilization of micronutrients in calcareous soils [

38].

Certain genotypes, such as Perseo, outperformed others in plant height and first-quality fruit yield (

Table 5,

Table 7 and

Table 11), thus underlining the significance of genetic selection in tomato production programs. As noted by [

41], innovations such as nanomaterials could improve nutrient uptake efficiency, optimizing genotype-specific performance. The initial hypothesis—that soil Ca availability was sufficient—was confirmed, and the results demonstrate that excessive application can compromise yield quality. This reaffirms studies questioning indiscriminate Ca fertilization, such as that by [

42], which demonstrated that excess Ca can induce Mg and K deficiencies, limiting tomato productivity. Genotypic differences in fruit quality attributes reflect previous findings regarding the moderate to high heritability of these characteristics in tomato [

43,

44]. The specific patterns of the genotypes also concur with the descriptions provided by the seed company regarding the vigor and stature of Toro and Palomo [

45].

The compost utilized in the second cycle, with a C/N ratio of 13:1, pH of 6.8, and EC of 4.5 dS m

−1, is classified as a mature, slightly alkaline material with moderate soluble salts. These characteristics favor both nutrient supply and the improvement of the soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties. Compost use increased plant height, an effect attributed to various processes: nutrient mineralization [

46,

47,

48,

49], improved soil structure and aeration, stimulation of beneficial microbial communities, and increased moisture retention. These effects enhance root development and aboveground biomass. The increase in stem diameter was consistent with improvements in soil organic matter, aggregation, and aeration [

50]. The stem diameters exceeded those reported by Ungaro [

51], which emphasizes the positive impact of the compost.

The compost did not show a significant effect on average fruit weight (

Table 14), a result that aligns with [

52], who found that poultry manure may increase fruit weight, though not always significantly. Differences in first-quality fruit weight between genotypes reflect their intrinsic genetic potential [

53]. The absence of effects on fruit diameter and length is consistent with [

54]. Nevertheless, other studies with higher manure rates or integrated organic and mineral fertilizers have reported positive effects [

55,

56], suggesting that the dose employed here may have been insufficient to induce morphological changes. Yield improvements, reflected in the number of fruits per square meter and total production, are attributed to the optimization of soil fertility through organic matter decomposition and microbial activity [

57]. The yields obtained (

) are consistent with reports associating poultry manure with increased tomato productivity [

46]. Variations across studies may stem from edaphic conditions, fertigation practices, and calcium interactions.

According to the results and the literature, the compost functions as a multifunctional amendment that improves soil structure, biological activity, water availability, and nutrient supply, contributing to increased productivity in intensive tomato systems. Conversely, calcium application is primarily beneficial in calcium-deficient soils. Supplementation is crucial where Ca limits growth; soil testing is mandatory [

58]. Susceptible genotypes, such as cultivars prone to blossom-end rot, respond favorably to Ca, particularly through fertigation [

59]. During critical developmental stages, flowering and fruit setting have high Ca demand [

60]. Likewise, factors such as high temperatures, low humidity, and salinity restrict Ca uptake; supplementation may be necessary [

61]. Techniques like fertigation and using Ca chelates enhance nutrient availability [

62].

6. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that, under the evaluated soil conditions, the intrinsic calcium availability was sufficient and the additional application of calcium at a 25% dose proved detrimental. The negative effect on fruit quality and yield is attributed to a specific interaction between calcium excess and the alkaline soil pH, which exacerbated nutrient imbalance and micronutrient deficiency.

In contrast, the application of the chicken manure-based compost functioned as a highly effective multifunctional amendment, significantly improving soil properties and promoting a substantial increase in total tomato yield.

It is concluded that the most efficient strategy for tomato production in this system is to prioritize organic soil management using compost and focus attention on the selection of high-yielding genotypes. Calcium application must be performed in a rational and targeted manner (preferably via fertigation) only after a soil analysis confirms a deficiency, thereby avoiding the indiscriminate use that compromises nutritional balance.