1. Introduction

Transportation development is a recurring topic in annual fiscal policies, particularly in developing countries [

1]. These initiatives are not only capital-intensive but also time-consuming and require a long time horizon for design and planning [

2]. To provide a tool for these tasks, traffic simulators offer the ability to realistically mirror real-world traffic and mimic dynamic vehicle interactions [

2,

3,

4]. Traffic simulators operate at different levels of granularity, typically classified as macroscopic, mesoscopic, or microscopic. Microscopic simulators model individual vehicles and their interactions at a fine level of detail, including traffic signals, road networks, and safety behavior. They are commonly used in applications such as vehicle behavior analysis, traffic flow optimization, intersection control, and safety evaluation [

3,

5]. Widely used MTSs include SUMO, PTV VISSIM, MATSim, AIMSUN, PARAMICS, TransModeler, AnyLogic, CORSIM, and MovSim, among others [

6,

7].

In previous studies [

8,

9,

10,

11], the choice of traffic simulator has often been driven by availability rather than by a thorough evaluation of simulator features. This often means that decisions are influenced by convenience or accessibility rather than technical rigor [

12,

13,

14]. Such an approach may overlook whether the simulator is truly suited for the research objectives at hand. The application of such simulators has, to some extent, met the needs of transportation planners; however, there exists an unsatisfactory result due to the performance imperfection of the simulators, especially on the microscopic scale [

15,

16]. Thus, it is necessary to understand the capabilities and limitations of each simulator to support an appropriate selection. Similarly, despite the widespread use of microscopic simulators, there is still a lack of quantitative methods to assess their computational efficiency and behavioral fidelity under comparable conditions [

8]. This poses a risk: a simulator chosen for the wrong reasons may fail to reproduce key behavioral patterns or may be computationally infeasible when applied to large-scale networks. As a result, planners and researchers may unknowingly base decisions on outputs that are biased by the limitations of the chosen tool. Hence, in this study, we developed a unified quantitative framework to evaluate and compare microscopic traffic simulators in terms of computational efficiency and behavioral fidelity, which we exemplarily apply to commonly used MTSs.

To support this decision-support process, this methodology requires consistent metrics to evaluate, compare, and classify the respective attributes of MTS tools. However, in order to ascertain this methodology, qualitative and quantitative metrics may be employed that both contribute to the assessment of simulator suitability. Qualitative factors such as support documentation, usability, and interoperability are often binary and straightforward to assess. In addition, existing studies often focus on qualitative feature comparisons or case-specific calibrations, without providing a unified benchmarking framework [

5,

8,

9,

11]. Hence, quantitative evaluation, particularly with respect to performance and behavioral fidelity, remains underdeveloped. Toshniwal et al. [

8] developed such a quantitative benchmarking approach using SUMO, but the proposed approach remains limited to computational efficiency. Similarly, Anyin et al. [

6] developed a quantification procedure to compare the qualitative features of traffic simulators; however, this method is still limited to qualitative features and does not evaluate microscopic quantitative features. Other studies have addressed MTS performance in specific contexts, such as the environmental effect of stop-and-flow traffic using VISSIM and TransModeler [

9]; the macroscopic phase transition behavior of TransModeler, VISSIM, and PARAMICS [

5]; simulation of border tolls using TransModeler, VISSIM, and AIMSUN [

10]; and differences in traffic modeling between SUMO and AIMSUN [

11]. Despite showing promising results, several important aspects remain underexplored and need to be expanded. To address this gap, this study is guided by the following research questions:

In addition to computational efficiency, what quantitative metrics should be used to compare microscopic traffic simulators?

Based on these metrics, how do selected MTS tools perform quantitatively?

The objective of this study is to extend a quantitative evaluation for the comparison of MTSs and focus on three metric categories: (1) computational efficiency (runtime, memory usage, and scalability), (2) dynamic traffic characteristics (safe gap distance and travel time), and (3) consistency of the simulators.

To avoid misinterpretations, we refer to runtime as the time it takes a simulator to compute the simulation in wall-clock time [

17]. Consistency refers to the capacity of simulation runs to reliably reproduce the same (or statistically consistent) results when the simulation is rerun under the same conditions. This notion is closely related to reproducibility, which has been identified as a major issue in transportation simulation research [

18]. The inclusion of the safe gap distance incorporates the concern of improving the safety measure and refers to the distance between vehicles in stationary or slow-moving traffic that provides sufficient time for vehicles to accelerate without crashing [

19].

The results of this study are directly relevant to transportation planners and modelers in agencies, as well as academics, who increasingly rely on microscopic simulations for strategic and operational analyses. By establishing a quantitative evaluation framework, this study contributes to the improvement of model transparency, reproducibility, and selection criteria in the practice of traffic simulation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the methodology, including the simulation filtration process, the selection of the test area, the generation of scenarios, and the development of a methodology for quantitative evaluation. The results of the comparative assessment are presented in

Section 3, focusing on key performance indicators (KPIs). Finally,

Section 4 concludes the paper, presenting key findings, discussing their practical implications, and providing an outlook for future research.

2. Methodology

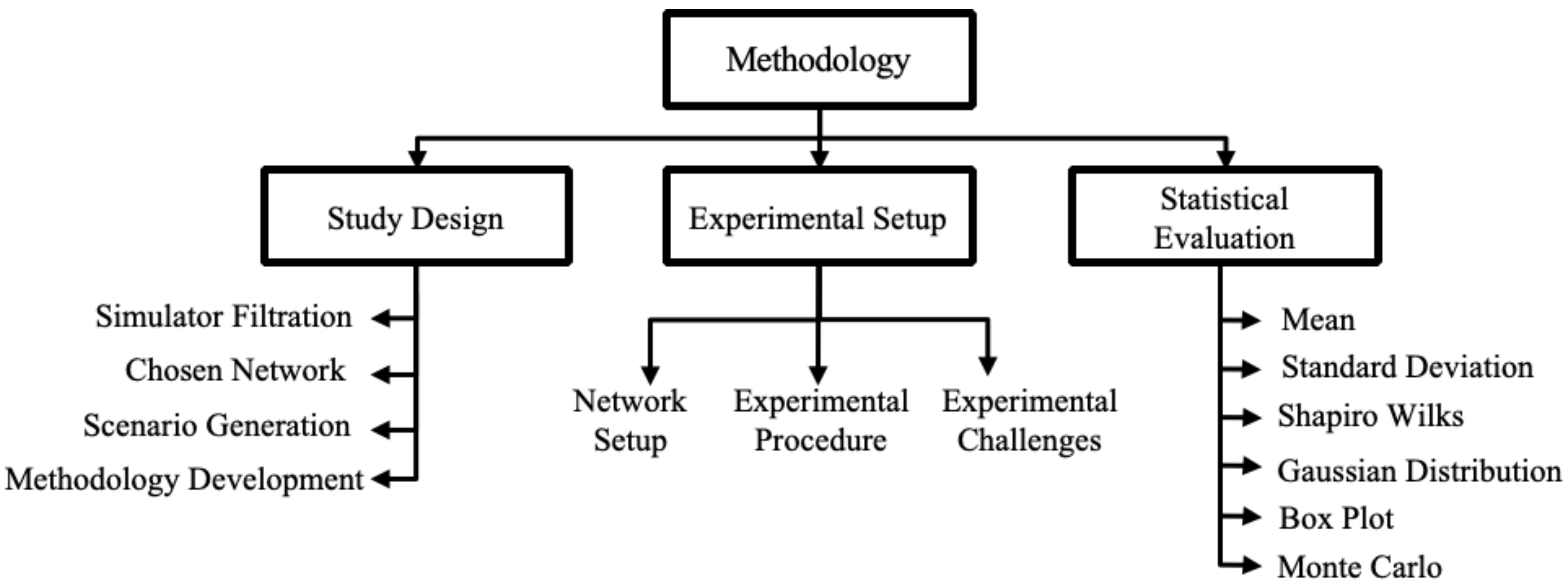

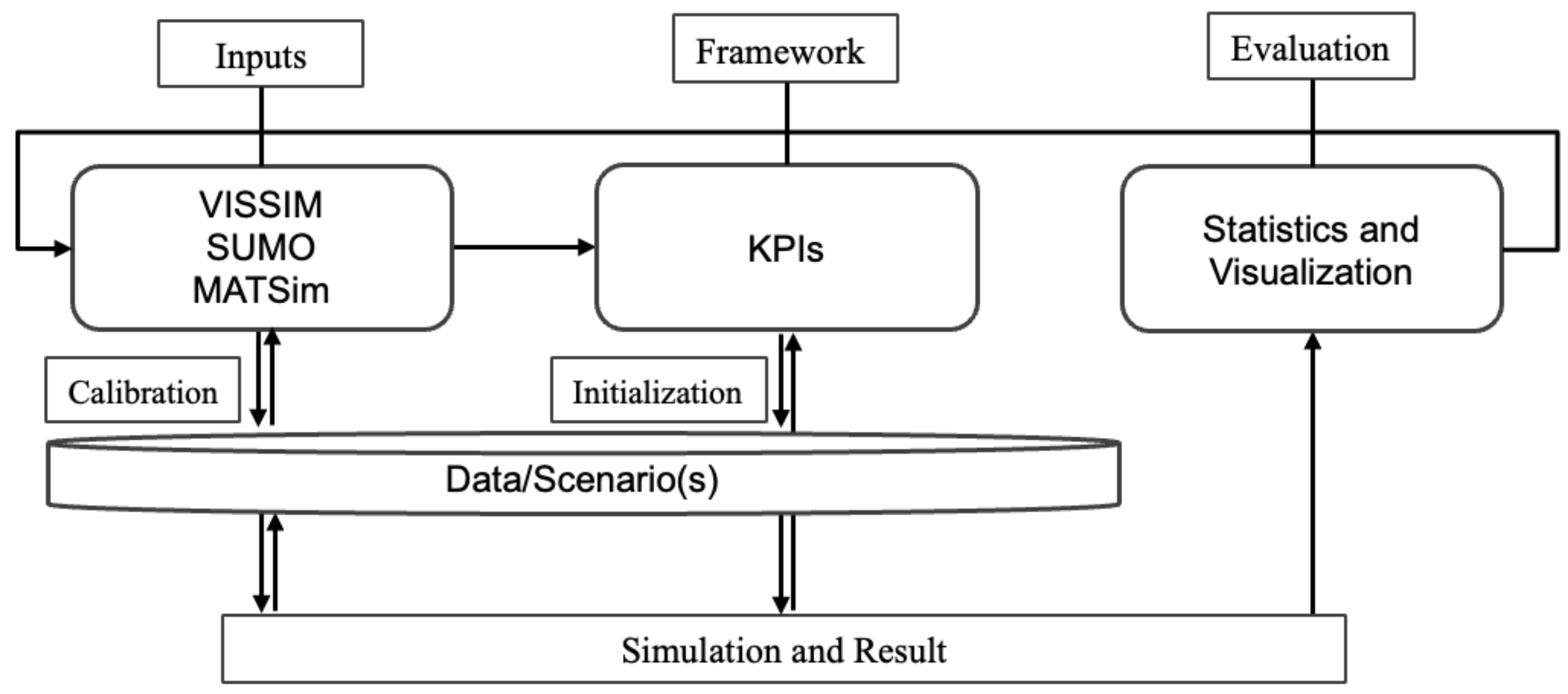

The methodology is shown in

Figure 1. The latter summarizes the approach in three stages: study design and evaluation criteria, experimental setup, and statistical evaluation (analysis and scoring). The study design consists of the following subprocesses: simulator filtration, chosen network, scenario generation, and methodology development. The experimental setup consists of the network setup, the experimental procedure, and the experimental challenges. The statistical evaluation consists of the mean, standard deviation, Shapiro–Wilk test, Gaussian distribution, box plot, and Monte Carlo simulation.

2.1. Study Design and Evaluation Criteria

In this first step, we selected the simulators through a pre-selection process, referred to as simulator filtration, which is based on a set of basic criteria.

2.1.1. Simulator Filtration

The selection of a specific simulator often depends on the specific needs and objectives of the study. For example, evaluating a particular dynamic traffic phenomenon may require a certain level of detail and network scale that only certain simulators are capable of providing. With geographic adaptation and accessibility (open source or commercial) being of particular interest, compatibility with OpenStreetMap (OSM) allows for the use of existing infrastructure data, providing the ability to simulate realistic traffic scenarios in real time. Hence, the preliminary collection of simulators was filtered using three qualitative criteria: (1) compatibility with OSM data, either natively or through a widely used and documented import workflow; (2) availability of open or customizable APIs for traffic calibration; and (3) support for microscopic or agent-based modeling. Because this selection focuses on geographic realism and the ability to construct networks from existing infrastructure data, OSM compatibility represents the primary filtration criterion.

Although only SUMO provides native OSM support, simulators such as VISSIM, AIMSUN, TransModeler, and MATSim have established OSM conversion pipelines (e.g., VISSUM, GIS-based tools, and OSM2MATSim). Therefore, these tools satisfy the geographic-adaptation requirement of the study. In contrast, simulators such as CORSIM, MovSim, UrbanSim, SCATS, PARAMICS, and AnyLogic lack native OSM support and any widely used or documented OSM import workflow. As a result, they cannot sufficiently support map-based network generation and were excluded. The complete filtration outcome is presented in

Table 1.

2.1.2. Chosen Network

Most MTSs are applied to networks of variable scale. However, research often emphasizes their ability to handle detailed agent-level behavior on different scales, placing heavy demands on speed, scalability, and adaptability for urban-scale simulation. To test these demands, this study defines two synthetic networks (small and large) and one real-world case. Including this real-world network is essential because it introduces real-life features, actual road geometry, demand fluctuations, route constraints, and topology irregularities, which synthetic networks lack. This lets us validate whether simulator behaviors (especially travel-time accuracy, handling of congestion and safe distances, and route choice) observed in synthetic tests also hold under realistic conditions. Thus, the real-world case acts as a benchmark of external validity.

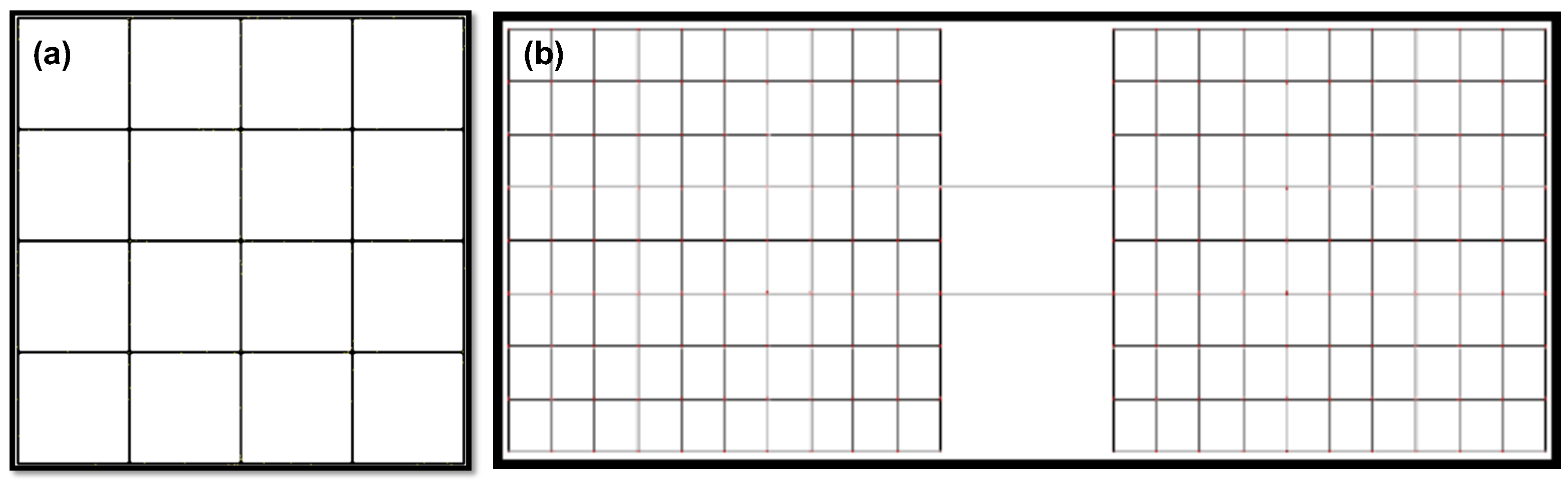

The small network is a single-lane dual carriageway extending 10 km within a 1 km

2 area, discretized into 250 m × 250 m cells (see

Figure 2). The large network is constructed to be ten times larger along the same structural pattern, representing a commuting corridor connecting two traffic zones under high inter-zonal travel demand. Thus, both synthetic networks test the performance of simulators under increasing scale and load.

In addition, the real-world network is based on the Kosciuszko Bridge segment in New York (NY) (

Figure 3), and trips are simulated between 95-81 Franklin St, Brooklyn, NY, and Hunters Point Ave, Long Island City, NY. The bridge provides a single natural, constrained path.

For the calibration of the simulators, certain traffic input parameters were used for the network segments, particularly the section illustrated by the red line in

Figure 3a. These parameters include the Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT), Design Hour Volume (DHV), Directional Design Hour Volume (DDHV), and percentage of trucks.

Figure 3b is the segment of the study network that shows the main route of the applied network. It contains 20 nodes for route connection and assists in the implementation of the network in other simulators. The models were calibrated using travel-time data provided by Drakewell [

20]. This traffic data was specifically used to calibrate the bridge section.

2.1.3. Scenario Generation

For each network, five scenarios with varying traffic densities and time tracking characteristics were generated, as shown in

Figure 2a,b. These scenarios are designed to assess how runtime, computational efficiency, and safe gap distance change under different traffic conditions. The scenarios are described in

Table 2.

2.1.4. Quantitative Evaluation Methodology

The methodology distinguishes between two frames of reference. The first is computational efficiency, which includes runtime, memory usage, and scalability. These KPIs represent how efficiently a simulator performs under computational load (scalability in MB) or by varying the size of the network (scalability in space). The second is dynamic traffic characteristics, which reflect how well an MTS is able to generate realistic traffic behavior. This includes travel-time accuracy, vehicle-to-vehicle spacing, and consistency of simulators under varying traffic conditions. The travel-time data obtained from Google Maps is provided in

Figure 4 and was used as a reference for this study. For a discussion of bias in the estimation of travel time, see [

21], and for precision aspects, see [

22]. Memory usage and scalability should not be mistaken; memory usage reflects the absolute resource consumption of the simulator when running a fixed-size network or scenario. It is a measure of how “lightweight” a simulator is in terms of memory footprint under normal conditions, while scalability reflects how well the simulator adapts (in terms of memory and runtime) when the demand or the size of the network increases. It is not just about memory; it is about how resource usage (both memory and time) grows (or, ideally, does not grow super-linearly) as the scenario size increases [

8,

12].

2.2. Experimental Setup

Due to licensing and hardware constraints, the study used SUMO 1.22.0, MATSim 2024.0, and VISSIM 2024.00-04 (

Table 1) for all tests. The tests were carried out with respect to the KPIs defined in

Table 3. In the case of SUMO, the internal TraCI Python API was used to access runtime statistics and agent behavior. MATSim used a Java-based controller and an event-handling system that allowed for access to agent-level data during simulation. For VISSIM, the component object model (COM) API was used in the Python library to extract relevant simulation metrics. These tools allowed for the consistent collection of performance data such as memory consumption, runtime, and individual vehicle states. All simulators were processed on an AMD Ryzen 7 3700X 8-core machine with a 3.6 GHz processor and 32 GB RAM. The test procedures involved the setup of the network and the experimental procedure.

2.2.1. Network Setup

To implement the network geometry, equivalent networks were used in all platforms. The simulator were set up differently, as illustrated in

Figure 5. Following the defined steps, the network was created for the respective simulators.

2.2.2. Experimental Procedure

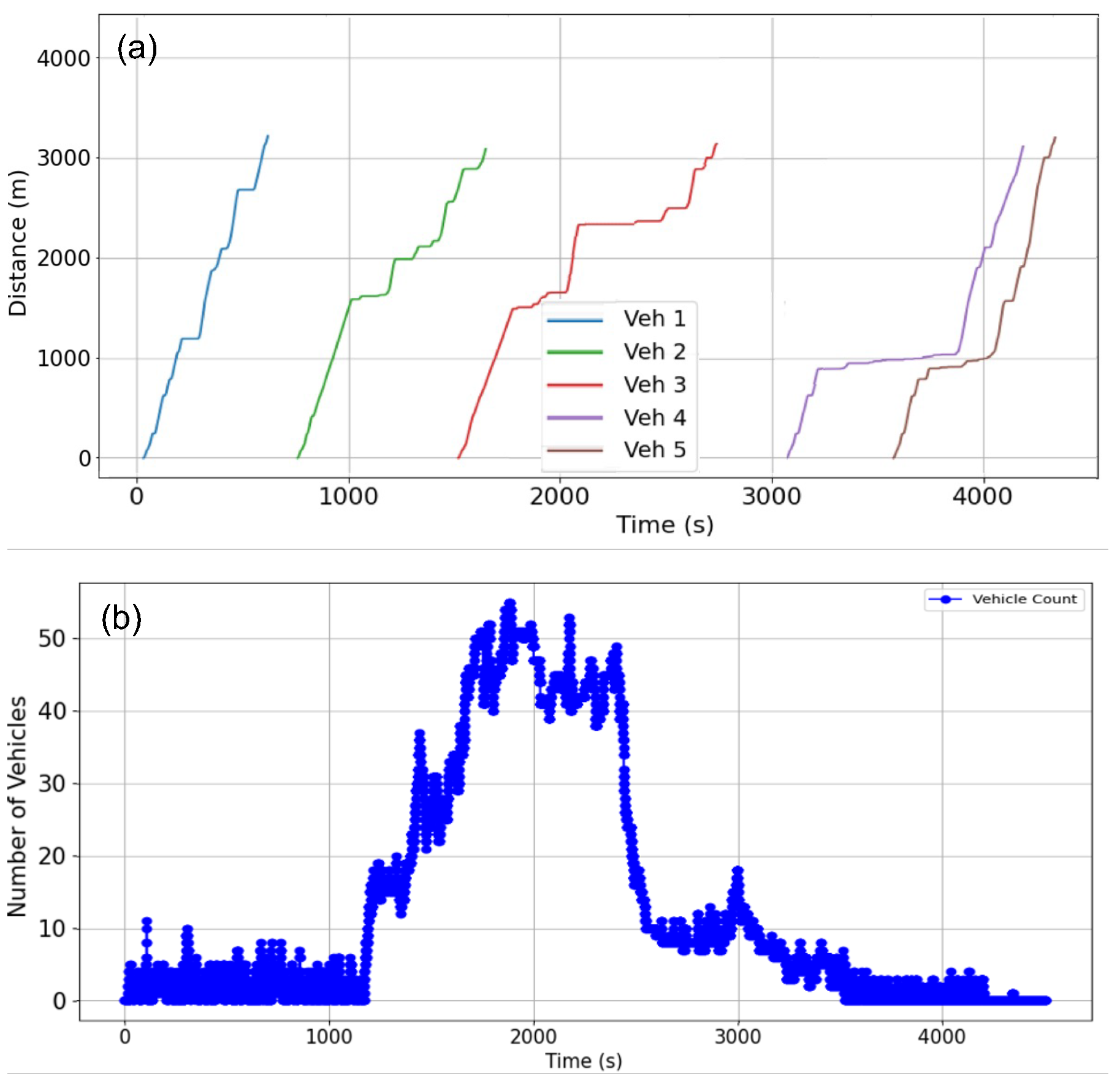

The procedure started with initialization and ended with an experimental implementation. The computational efficiency of the timing and speed of the simulator was initialized to zero (0), and an external stopwatch was installed alongside a Python script for runtime verification. After that, the script was used for runtime monitoring. The computer processor was freed of any other processing programs, and the routes and agents were conditioned to travel at the highest speed. For the travel-time punctuality test, using the defined speed (50 kmh−1), five probe vehicles were monitored at the beginning, middle, and end of the simulation.

Regarding

geometric and flow calibration we considered random traffic input volume for all scenarios except scenario V. For scenario V, the respective simulators were calibrated against the geometric characteristics, which reflect the approximate number of nodes (20; see

Figure 3b) and their corresponding routes. Geometric calibration followed the procedures demonstrated in

Figure 5, benchmarked with the fragmented travel route provided in

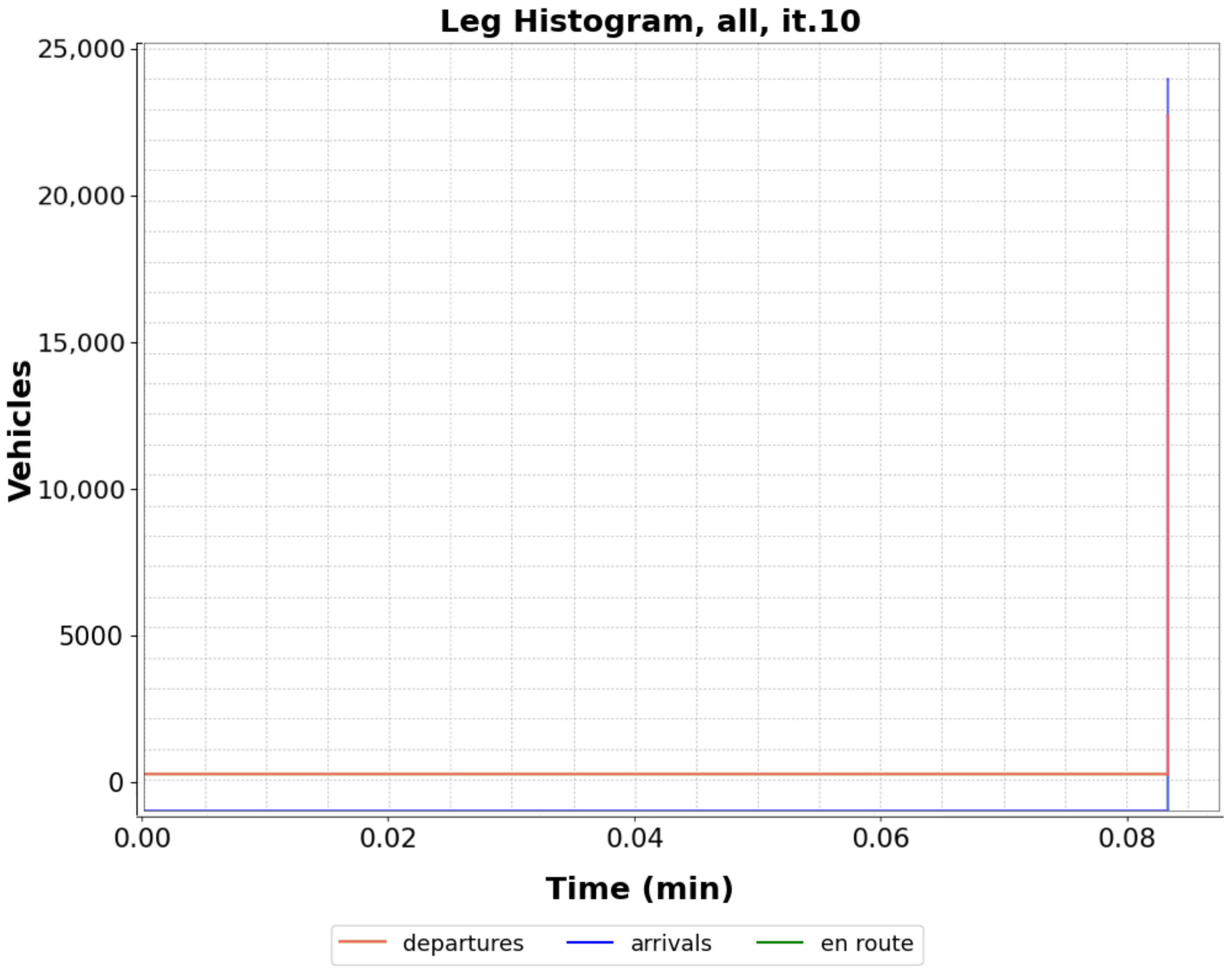

Figure 3b. The traffic volumes per hour of the system for VISSIM (using the data collection points), SUMO (using D3 detectors), and MATSim (Leg Histogram, all, it.png) were calibrated, and their respective accuracies are provided in

Table 4. The outcome of the calibration is provided in

Appendix A.1 (see

Figure A1).

Consistency covers the range of dependability of the methodology and the level of stability or variability of the simulators. To avoid relying on single-run tests, 50 trip files each of the first two scenarios I and II were developed, each with randomly distributed traffic. To evaluate the stability of the runtime and memory used in the simulators, we measured the standard deviation of the simulation runtime and memory used over 50 iterations with the same traffic scenario in scenarios I and II. The mean, standard deviation, range, min/max, and Shapiro–Wilk test were used to check the distribution and runtime stability of the simulation. Traffic simulators can yield different results, even under identical input conditions due to randomized vehicle routes, stochastic agent behaviors (e.g., gap acceptance, acceleration, and deceleration), and nondeterministic simulation algorithms (especially in agent-based models like MATSim). Thus, a Monte Carlo simulation was applied to repeat the simulation with randomly generated traffic inputs (1000 iterations) to observe the distribution of key performance metrics such as runtime and memory used. The latter were monitored with a Python script provided in [

24], and the used memory was manually monitored in the system task manager. The execution procedure of the remaining KPIs for each of the simulators is discussed in the VISSIM, SUMO, and MATSim sections below. For VISSIM, random vehicle routes were used repeatedly to meet the iteration requirements.

For

VISSIM, after implementing the network for scenarios I, II, III, and IV, the duration of the simulation was initialized and increased to its limits. Random vehicles were added using the vehicle input prompt, and random vehicle routes (route decisions and multiple routes) were used in the built-in network object tool to create the network flow. Vehicles were randomly assigned to the routes for the respective scenario numbers. A Python script provided in [

24] was created to record the runtime and utilized memory using the COM API. Regarding scenario V, the OSM network file was processed using VISSUM as a shape file and imported into the VISSIM environment. The bridge was calibrated to the stated AHV using the vehicle travel time, and start and end lines were initiated (see

Appendix A.1,

Figure A1). The travel time was extracted using the built-in simulator measurement tool (see

Appendix A.2 for details), and the visualization is provided in

Figure 6a. For the safe gap distance, we used the scenario IV traffic jam and the measure distance icon in the network editor toolbox, and the distances between queued agents were measured and recorded. The systemic test procedure for all simulators was designed as illustrated in

Figure 7.

For

SUMO, after creating the network using the Netgenerate command, trip files were created using the randomtrips.py command in the SUMO Python library and, along with the network file (net.xml), to form a configuration file for each of the scenarios. The configuration file was loaded into a Python script provided in [

24]. Using the TraCi library, the runtime was measured and recorded in all scenarios. The fifth scenario was used to measure the travel time using the OSM file of the scenario in SUMO. The TraCi library was used to run the simulation, and the average travel time from the target origin to the destination was recorded. The graphical user interface is provided in

Figure 6b. A corresponding graph of traffic demand and traffic pattern is illustrated in detail in

Appendix A.2 (see

Figure A2). The safe gap distance was monitored and measured using the simple ratio of the vehicle to the space distance of the screenshot of the congested vehicle provided in

Figure 8, using the agent sizes in the SUMO guide book.

For

MATSim, three network.xml files were created, each replicating the test areas. Four plan.xml files were generated, and a configuration file was created containing the plan.xml and network.xml files. The first four scenarios were generated using the Python script provided in [

24]. Fifty of the first two scenario plan.xml files were generated with random trip plans (using the same Python script). Then, simulation of the four scenarios was performed. We used OSM2MATSim GITHUB files provided by SIMUNTO management for osm-to-MATSim file conversion, resulting in conversion to a MATSim Net.xml-enabled file. This file was executed, setting the processing speed to the scenario specification as shown in

Figure 6c. The time taken to traverse the bridge to the destination was recorded using the vehicle details event file (stopwatch.png) provided in

Appendix A.2 (see

Figure A4). Traffic-flow calibration was determined using the output iteration file (Leg Histogram All) provided in

Appendix A.1 (see

Figure A3). For the fourth scenario, the gap distance was measured from the queued spot in the network between the two zones using the built-in metric ruler in the SIMUNTO interface (see

Figure 8).

2.2.3. Experimental Challenges

Due to challenges in tracking memory usage directly within MATSim, the memory consumption of other simulators was manually monitored using the system’s Task Manager API. In scenarios I–V, MATSim was run from iteration 0 through iteration 10, representing its single test cycle. Unlike VISSIM and MATSim, SUMO does not have an internal rule to manage certain simulation constraints. In generating the VISSIM simulation, the agents were very realistic and did not teleport in jams; this led to longer waiting times. We activated vehicle removal after 10 s of standstill to prevent freezing; this allowed the simulation to continue. In addition to terminating the jams, extra links (exit links) were created and attached to the main network with parking lots for the trips to end. While simulating scenarios II, III, and IV in VISSIM using 20,000 or more agents, the simulation speed dropped, and the simulator produced several freezing warnings. To overcome this, the capacity of the networks for scenarios II and IV was adjusted (biased). The simulation time step for SUMO was initialized to ; however, this can be lowered at the risk of freezing, especially for scenario IV.

2.2.4. Scalability Measures

Scalability is defined as the relationship between memory consumption and runtime between different volumes of traffic and network sizes [

25]. This study used scalability indices derived from basic performance engineering principles and general scalability technical analysis used in high-performance benchmark analysis [

26]. We defined three key metrics—the Memory Scalability Index (MSI), Runtime Scalability Index (RSI), and Combined Scalability Index (CSI)—as measures of scalability. These metrics were used to evaluate how resource requirements grow with an increasing number of simulated agents.

The Memory Scalability Index (MSI) measures the change in simulation memory usage with respect to an additional agent, i.e.,

where

and

represent the number of agents and

and

represent the memory usage (in MB) for agents

and

, respectively. In the mathematical expression in (

1), lower MSI values indicate better scalability.

The Runtime Scalability Index (RSI) measures the growth of the simulation runtime with respect to changes in agent count, expressed as

where

and

represent the runtime (in seconds) for agents

and

. Like the MSI, a lower RSI means better performance. The use of the RSI and MSI is the classical methodology derived from Jain’s formulation [

26].

To aggregate the scalability index, this study defined the Combined Scalability Index by normalizing the MSI and RSI and computing their index average defined via

where

and

are the observed changes in memory and runtime, respectively, and

and

are the maximum values observed among all simulators. The CSI is novel and framed to allow for comparative evaluation across simulators. Currently, there is no existing inference for verification and reference. A higher CSI implies greater overall scalability.

Metrics of memory usage, runtime, runtime consistency, travel-time accuracy, safe gap behavior, and scalability were selected because they represent both behavioral fidelity and computational efficiency. Memory and runtime directly affect the feasibility of large-scale microscopic simulations, while travel time and safe gap distance reflect the model’s ability to reproduce realistic driver–vehicle interactions. Consistency and scalability provide measures of stability and robustness under increased network or demand size and are critical for regional-scale planning applications.

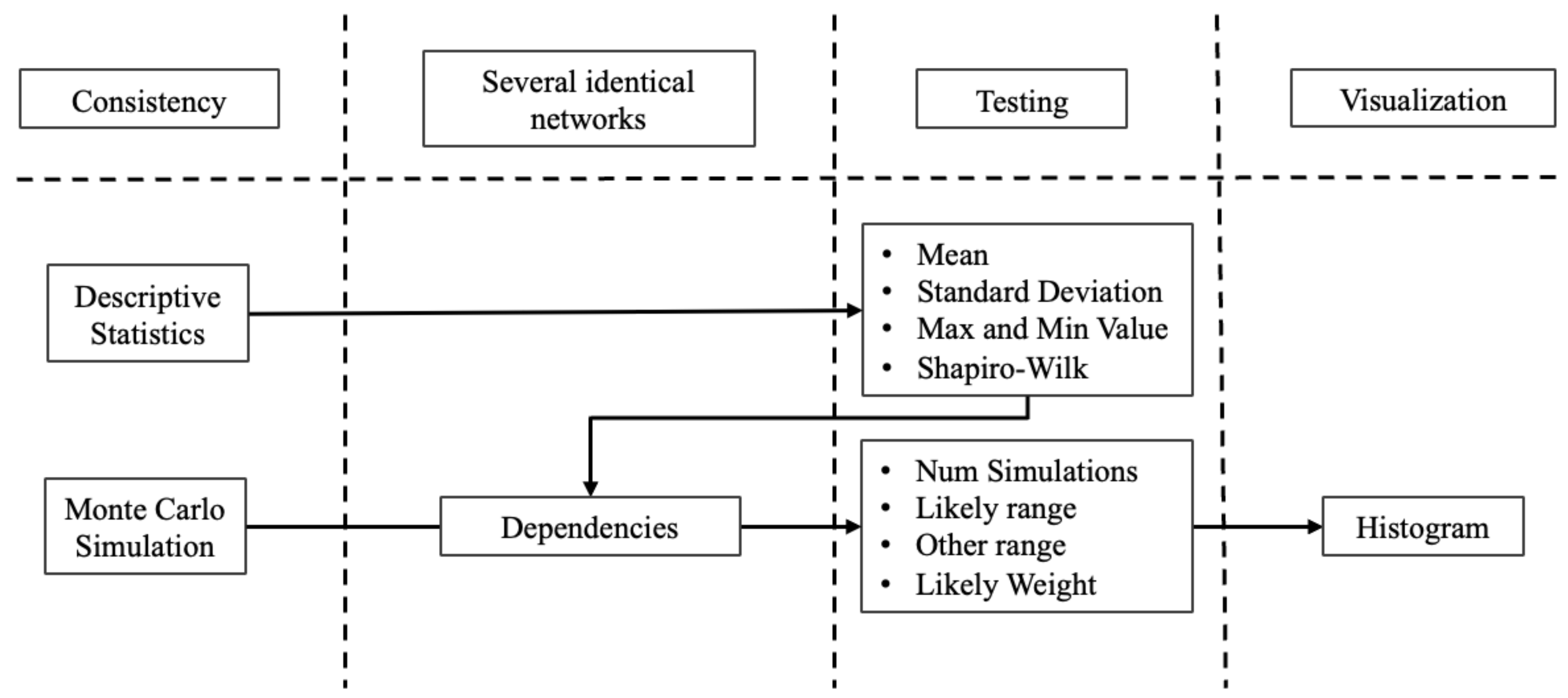

2.3. Statistical Evaluation

The results of the simulations were analyzed to identify performance patterns and trends across the considered simulators. Each of the latter was assessed on the basis of the defined KPIs. Most of these tools are Monte Carlo dependencies, as demonstrated in

Figure 9.

The

mean () is the mean of the simulations of each of the applied simulators, i.e.,

Here, is the simulation runtime for each iteration, and n is the number of iterations.

The

standard deviation () measures the deviation of the simulator output from the mean output data after multiple iterations, covering the output of the respective simulator as defined in the scenarios:

where

is the mean of the dataset and

n is the number of iterations applied.

Shapiro–Wilk likelihood estimation is a tabular approximation test used to study the consistency and probability of reproducibility of the simulation. It does not have a simple closed-form expression for the p-value; rather, it is computed numerically using pre-tabulated values. However, the test statistic (

w) has a formula, and the

p-value is determined based on

w and the sample size.

Here, refers to the null hypothesis, is the order statistic (that is, the sorted values), is the sample mean, and is the constant derived from the expected values of the order statistics of a normal distribution.

The

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the average magnitude of errors between the simulated and actual travel time and safe gap distance via

without considering direction, whether the simulation results are above or below the true value. Here,

n is the number of observations,

is the actual value, and

is the predicted value.

The Monte Carlo method is a statistical technique that utilizes the random outcome of each simulation and the corresponding probabilistic modeling to estimate the numerical results. It is especially useful for solving problems that are deterministic in principle but too complex for analytical solutions, especially in repeated iterations.

3. Results and Discussion

The measurement of the simulator capacity requirement is scaled in three map sizes that are varied in density across five scenarios as defined in

Section 2, which provides a basic understanding of the respective strengths of the simulators. Therefore, this section covers the results of the comparison and the questions created as a result of the methodological development. The outcome is split and discussed separately for runtime, memory usage, travel time, gap distance, consistency, and scalability.

3.1. Runtime

The runtime was determined using scenarios I, II, III, and IV, and the result is reported in

Figure 10. The processing performance of the participating simulators is statistically determined in the four runtime scenarios. The results of the runtime evaluation of the simulated mobility patterns collected from VISSIM, SUMO, and MATSim are analyzed.

Scenario I: SUMO and MATSim demonstrated relatively fast performance compared to VISSIM. This can be attributed to the sample space available in the network, which allowed agents to move freely and allowed each simulator to perform optimally under low congestion.

Scenario II: The agents in this network were constrained in their movement because the space was limited. All simulators faced performance restrictions, but MATSim showed strong resistance to stop-and-flow behavior due to the nature of its car-following logic (queue-based simulation) and the used behavioral modeling techniques. Notably, VISSIM processed simulations efficiently for agent counts up to 12,000; however, beyond this threshold, the simulation encountered errors, necessitating an increase in network capacity.

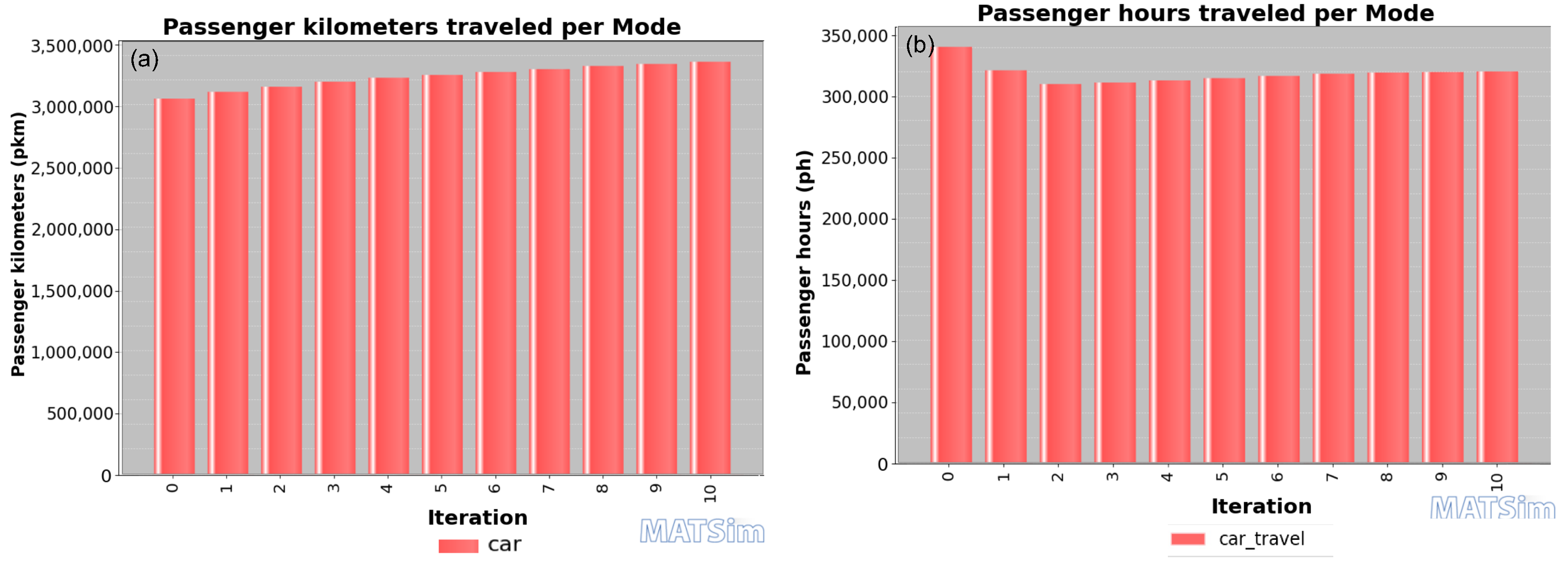

Scenario III: Agents were required to traverse a larger and less congested network, and SUMO outperformed the other simulators. Its faster performance can be attributed to the superficial behavioral modeling of the simulator (Dijkstra algorithm), which prioritizes the shortest path and the minimum travel time. In contrast, MATSim relies on an iterative replanning methodology based on agent behavior, which produces realistic results but requires more computational resources to traverse a network, as shown in

Figure 11.

Scenario IV: The performance of all simulators decreased when the network became more congested due to system overload. System overload caused the memory usage to increase, as shown in

Figure 11. The memory usage of SUMO and MATSim increased because of SUMO agents causing congestion, and MATSim applied iterative replanning. VISSIM showed a linear increase, as demonstrated by the real-time factor (the ratio of the simulation time to real-world time expressed as a factor) as the number of agents increased.

This metric expresses the performance and scalability of the simulators at different network scales. However, there is a relationship between density and runtime. The tenth factor, at a larger scale, consumed more energy, requiring more computational resources. Although the scale increased by a factor of ten, the performance of VISSIM showed minimal variation despite the corresponding increase in the number of agents (objects). It can be observed that runtime is directly proportional to the scale of the network and the variation in density, as shown in [

8]. It is evident in both small- and large-scale scenarios, with a proportional increase in traffic volume. The comparative analysis in

Figure 10 shows that the increase in density by the tenth factor increases the runtime disproportionally between the simulators. VISSIM consistently required longer runtimes in all four scenarios. In contrast, SUMO demonstrated a moderate runtime in the third scenario, primarily due to the prevailing traffic density.

3.2. Memory Usage

Similarly to the previous section, the simulation memory usage test was performed in the four scenarios (I, II, III, and IV) for each participating simulator. The results presented in

Figure 11 clearly demonstrate that both VISSIM and MATSim exhibit a gradual and consistent increase in memory usage in all scenarios. This gradual increase is due to the way VISSIM and MATSim are optimized to avoid unnecessary memory spikes and to manage agent data and network complexity [

27,

28]. In contrast to other simulators, the memory usage of SUMO increases with increasing traffic density (especially in scenario IV), which is consistent with the findings reported in [

8]. Based on the memory distribution in the fourth scenario, VISSIM has a higher memory demand. This is attributed to the logic of the car-following model (lane-changing, acceleration and deceleration profiles, driver psychology, and reaction time), in addition to the detailed interaction and real-time graphical rendering visualization (fine-grained geometry), which rely heavily on CPU and memory resources. Generally, it is evident that a rapid increase in traffic generation leads to a corresponding increase in memory demand. For SUMO, this is shown in

Figure 11b for scenarios II and IV.

When comparing the simulation results in the test scenarios, as shown in

Figure 11, the resource consumption is highest in scenario IV. As a result of higher traffic demand, more memory is required to run the simulation. Conversely, we observed that scenario III took less memory because it has a low traffic density. In traffic systems, traffic demand is the product of velocity and density. The demand reduces to zero as the velocity approaches zero; hence, the density increases. However, high density may be generated from the propagation of queues between nodes. Excessive density leads to congestion, resulting in increased times. As demonstrated in

Figure 11 for scenario IV, VISSIM and SUMO exhibit this qualitative realism defined by their car-following models; however, MATSim showed a characteristic of transient, slow and steady flow, as evidenced by the insignificant increase in memory usage.

3.3. Travel Time

The travel-time accuracy results are illustrated in the box plot shown in

Figure 12, while the reference values in the real world are illustrated in

Figure 4.

In

Figure 12, it can be seen that the defined travel time of the probe vehicles of the simulators shows mean deviations of

,

, and

for VISSIM, SUMO, and MATSim, respectively. The higher variation in MATSim can be attributed to the overflowing behavior of the QSim module, which is based on queue-based simulation dynamics. The QSim module operates on a first in–first out (FIFO) basis and is designed for high scalability. However, it shows a higher processing speed for low-density scenarios (>2000 agents), which explains the observed deviations in simulation performance. This is in agreement with the findings reported in [

29]. Recall the behavior of MATSim in

Figure 10c and

Figure 11c, where the agents are not restricted by congestion; instead, their movement follows the allowable travel speeds defined by the network geometry rather than being dynamically influenced by state–action interactions. This reflects MATSim’s queue-based methodology, where agent movement is rule-based rather than governed by continuous state–action feedback mechanisms such as those found in VISSIM or SUMO. However, there has never been any travel-time study of MATSim for inferences and comparison. In contrast, VISSIM models individual vehicle dynamics with detailed state–action interactions such as lane-changing, car-following, and reaction to real-time traffic conditions. SUMO also supports real-time traffic flow adaptation, offering a middle ground in feedback. Conversely, VISSIM uses the Wiedemann car-following model, which is a microscopic and behavior-based car-following model that is not strictly deterministic; instead, the agent’s behavior is state-defined. Consequently, MATSim demonstrates higher computational efficiency but may under-represent the dynamic effects of congestion compared to VISSIM and SUMO.

3.4. Safe Gap Distance

After calibration of the network geometry and repeated iterations under defined assumptions, a comparative analysis of the safe gap distance was performed. The results are presented in

Figure 13.

The percentage errors for VISSIM, SUMO, and MATSim are

,

, and

respectively. The response of MATSim to this measure is particularly unstable due to its car-following model. Agent performances in MATSim do not tail; rather, they lead (free flow), operate independently, and are not constrained by leading vehicles. With the FIFO car-following model, there is no explicitly defined gap distance in the documentation or supporting literature. In contrast, VISSIM and SUMO implement microscopic traffic models in which agents are constrained by the availability of space ahead, requiring them to wait (stop) until the leading vehicle has cleared. This performance agrees with their respective documentation [

30,

31]. The relevance of this distinction becomes apparent when the gap distance exceeds the allowable distance, as this directly affects vehicle accommodation and road capacity. As such, incorporating safety considerations such as minimum safe gap distances into simulation models is essential. This motivation is supported by Hunt et al. [

32], whose work emphasizes the importance of behavioral realism in modeling. Consequently, this serves as a reminder for simulator developers to reflect on safety-critical parameters within their traffic modeling methodologies, such as the gap distance.

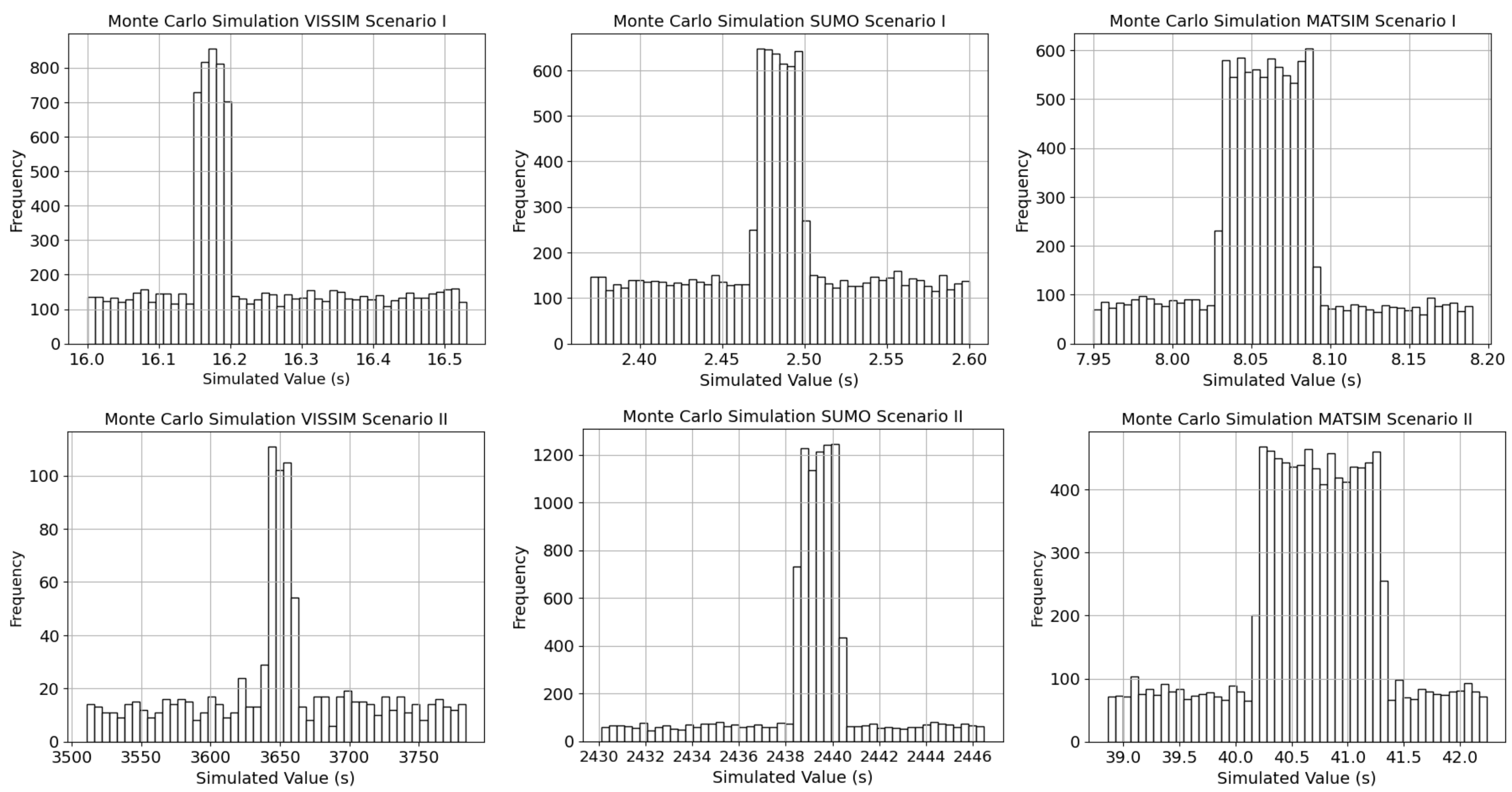

3.5. Consistency Analysis

The consistency of the simulators for scenario I is presented in

Figure 14 and

Table 5. However, this reveals the tendency for performance to spike or deviate in repeated trials in randomized traffic simulation environments. In the event of simulation reproduction, the confidence level provides the extent of the variation. Such a condition is necessary to understand the dependable range of the simulators under varying conditions, as shown in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Based on the distribution of

Table 5, using the Shapiro–Wilk test, the

p-value represents the probability of achieving similar performance under repeated trials. Similarly, a

p-value greater than

indicates that runtime or memory usage follows a normal distribution, implying that the simulator produces consistent and predictable results across multiple iterations. In contrast, a

p-value below

suggests skewness or non-normality, indicating that the simulator’s output is more sensitive to stochastic variations in traffic input or internal randomization. Based on the estimated values, the likelihood of having the same outcome in the event of reproducibility is higher in MATSim (

) and lower in VISSIM (

), indicating greater variability in repeated trials. This is likely caused by VISSIM’s detailed car-following and driver behavior modeling, which introduces additional stochasticity. SUMO has a higher p-value, although the Dijkstra algorithm is deterministic [

33]. Hence, the distribution provided in

Figure 14 is in agreement with MATSim and SUMO, showing symmetrical features around the mean. This interpretation reinforces the fact that agent-based or iterative frameworks (MATSim or SUMO) maintain more stable computational performance, while behaviorally rich simulators (VISSIM) may produce more variable results depending on network dynamics.

In

Table 7 and

Table 8, it is revealed that there is a mismatch between the runtime and the memory utility, since a high-consistency probability in the memory utility may show a low-consistency probability in runtime. SUMO, for example (in scenario II), showed high consistency, with a high frequency of occurrence in the mean region in the runtime, a numerical output of 89% probability of consistency, and a very low consistency of 2% in memory utility. In contrast, VISSIM showed a moderate consistency in memory utility of 48 % and a low consistency runtime probability of 34%.

3.6. Scalability

In order to measure the scalability of the simulators, scenarios II and IV were used. This is attributed to the increase in the number of agents from scenario I to scenario II and, similarly, from scenario III to scenario IV. However, this difference is noticeable in the increase in memory, as shown in

Figure 11. Based on

Table 9, we assume that M and R represent the values of memory used and runtime for scenarios II and IV, as shown in

Figure 10. The table shows the scalability investigation index of VISSIM in the 1

and 10

networks, with a total ten-factor increase in the number of agents to

and

for the memory and runtime index, respectively. This is aggregated to 0 CSI in the normalization expression. Similar results were observed for SUMO and MATSim, scoring index values of 0.530 CSI and 0.74 CSI, respectively. MATSim has the highest CSI value of 0.741 CSI, compared to 0 CSI for VISSIM. This shows the suitability of this simulator for large-scale network simulations. This is discussed in further detail in the Summary and Discussion.

3.7. Classification

The basic statistics judging the performance of the defined KPIs under varying randomized traffic are studied and summarized in this section. The general classification of the simulators, as presented in

Table 10, provides a summary of the key findings and a comparative assessment of their respective strengths. A summary of the findings of this study is provided in a spider chart in

Figure 15, where each metric was normalized via

where

is the measured value of the

i metric [

6].

3.8. Summary and Discussion

The comparative analysis of runtime across varying traffic densities revealed that VISSIM exhibits a low processing speed in dense networks that exceed 12,000 agents. However, with fewer agents (fewer than 12,000 agents), particularly within a 1 km

2 network, it performed more efficiently and reliably. In large-scale scenarios, MATSim consistently outperformed the other simulators in dense networks without replanning conditions, showing minimal to no evidence of traffic clustering. This performance advantage was particularly evident at higher density thresholds ranging from 20,000 to 100,000 agents, where VISSIM exhibited significantly longer processing times and reduced scalability. In SUMO, beyond 100,000 agents, network instability was observed, known as freezing. These observations are consistent with previous findings in SUMO by Juan et al. [

34].

In contrast, MATSim benefits from a more permissive car-following model [

35], in which vehicles operate largely independently. This results in fewer queues and smoother flow but at the cost of reduced realism in congested traffic conditions. When configured with queue-based mobility simulation (QSim), MATSim reproduces real-world congestion dynamics better. Its stable runtime performance across repeated trials makes it highly suitable for large-scale simulation, as demonstrated in

Figure 15. The runtime speed was lower due to its lightweight agent behavior and efficient event-based execution. MATSim can also use other car-following models, like Dijkstra and ASTarL, but uses SPeedyALT by default.

In terms scalability, each simulator was evaluated under increasing network and demand sizes (scenarios I–IV). The results are interpreted as near-linear runtime growth for MATSim and sub-linear behavior for SUMO, while VISSIM exhibited exponential increases due to its detailed vehicle interactions. These findings confirm that the proposed methodology effectively quantifies scalability as a distinct performance dimension, which is relevant for large-scale implementations. In detail, SUMO repeatedly demonstrated efficient agent instantiation and moderate memory requirements. These findings are supported by Song et al. [

36], who noted that simulators based on Wiedemann and Krauss-based car-following models tend to reflect stop-and-flow behavior and form realistic clusters, especially near intersections. This clustering was more evident in VISSIM and SUMO but varied in degree and structure.

In scenarios I–III, all simulators demonstrated acceptable scalability. However, only SUMO and MATSim maintained performance as the traffic scale increased further. Their reduced interaction fidelity at high densities leads to more efficient computation but less realistic traffic dynamics. In contrast, VISSIM’s detailed modeling of vehicle interactions provided increased realism but required significantly more computational resources under load.

Regarding travel-time accuracy (see

Table 10 and

Figure 12), SUMO provided the best match to real-world expectations, likely due to its consistent vehicle speeds and smoother flow patterns. VISSIM also showed reasonable alignment. In contrast, MATSim significantly deviated from real-world travel-time distributions, as its agents traversed the network under the control of QSim, causing realistic delay or queuing behavior.

For safety-related measures, SUMO, again, performed best, with the lowest error in reproducing realistic safe gap distances (0.0081). MATSim, due to its independent agent logic, showed the highest deviation. VISSIM provided the most realistic representation of following behavior, accurately replicating empirically supported safe gap distances in the range of 1–2 m [

19].

The observed differences in simulator performance can be directly attributed to the underlying model architectures and behavioral representations of the simulators. MATSim, based on a queue-based, event-driven agent architecture, emphasizes large-scale behavioral adaptation and scalability. This structure allows for efficient simulation of extensive urban networks and policy testing scenarios where computational performance is critical. SUMO, which employs a continuous-time microscopic car-following model (Krauss), balances computational efficiency with realistic vehicle dynamics, making it suitable for congestion management studies, traffic control algorithm testing, and connected vehicle applications. In contrast, VISSIM relies on the Wiedemann psycho-physical car-following model, which provides detailed interaction dynamics such as lane-changing, acceleration, and reaction time, allowing it to replicate fine-grained driving behavior more accurately. Consequently, VISSIM is best suited for automated vehicle testing, safety evaluations, and signalized intersection analysis, where the fidelity of microscopic behavior is paramount. This contextual link between simulator design and observed performance underscores that no single simulator is universally optimal, and selection should align with the intended application domain and the granularity of the modeling.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

The inclusion of behavioral metrics in this study ensures that the comparison is not limited to computational performance but also includes the ability of each simulator to represent realistic traffic flow phenomena. This study addressed scalability with a formalized approach defined as the Memory Scalability Index (MSI) and Runtime Scalability Index (RSI). This approach was derived from the classical performance analysis described by Jain [

37]. Furthermore, we suggested a Combined Scalability Index (CSI) to aggregate and normalize the MSI and RSI values, offering a single interpretable indicator for comparative scalability assessment. The comparative illustration in

Figure 15 shows that no simulator performs best in every case; each has trade-offs depending on the scenario and metric. However, SUMO and MATSim showed good performance in runtime and memory consumption, especially in large-scale scenarios. However, MATSim performed better in scalability. SUMO also showed the lowest energy demand for a large scenario and compensated better for computational requirements. VISSIM offered a faster runtime with a simulation threshold of 1000 to 12,000 agents and replicated detailed (fine-level) microscopic traffic behavior at lower traffic volumes (fewer than 10,000 agents).

For travel-time accuracy, VISSIM matched closely with reality. For safe gap distance, SUMO offered the most accurate result. Based on statistical analysis, all simulators showed a decent level of consistency in the randomized test, as indicated by the Shapiro–Wilk test scores and the average deviations in runtime and memory usage. This enables transport agencies and practitioners to understand which simulator performs best according to their needs.

Recommendation

The choice of a simulator should reflect the project’s technical requirements, target scale, and available resources. The proposed comparative methodology can help make this choice more transparent. Based on the limit of microscopic traffic of the studied simulators, within the defined scope of the performance analysis, this study recommends VISSIM for fine-grained, detailed microscopic traffic simulation. Future work should look at more simulators, focus on improving interoperability and real-time performance, and encourage open libraries to support collaboration.