1. Introduction

Road and traffic safety is inherently multidimensional, involving the interaction of human, vehicle, roadway, and environmental factors. Elements such as road geometry, pavement condition, vehicle type, and roadside infrastructure are integral to crash occurrence and injury outcomes, alongside behavioral factors like impairment or non-use seatbelt. The present study considers this full spectrum of variables, integrating both human and infrastructure-related attributes reported in the crash and roadway databases. Traffic crashes remain a significant global burden, contributing to public safety risks, widespread injuries, and notable economic losses. In the United States alone, tens of thousands of individuals are killed each year, while hundreds of thousands more suffer injuries ranging from minor to life-altering. Understanding and reducing crash-related injury severity is a key priority for transportation agencies and public health policymakers. While a few recent studies, such as Hasan et al. (2024), have applied sensitivity analysis to assess how changes in explanatory factors influence crash severity outcomes [

1,

2], these efforts remain limited in scope. Such work typically relies only on structured variables and focuses on crash-level severity, often assigning a single severity label to an entire event. This study integrates both structured crash records and unstructured narrative text to better model injury severity at the individual level. Furthermore, beyond measuring variable importance, the analysis simulates potential changes to key variables, providing more actionable insights for prevention and policy. The main objective of this study is to develop an integrated machine-learning framework that combines structured crash data and unstructured police narratives to predict individual-level injury severity and evaluate how modifications to key variables influence injury outcomes. Specifically, the research aims to (i) enhance prediction accuracy through narrative-based feature extraction, (ii) identify the most influential factors contributing to crash-injury severity, and (iii) translate these insights into actionable prevention strategies using simulation-based sensitivity analysis.

This research adopts a three-step approach: first, identifying the most influential predictors using feature-importance techniques; second, selecting the best-performing machine-learning model for injury-severity prediction; and third, conducting simulation-based sensitivity analyses. In these simulations, each key variable (particularly those with practical potential for modification) is systematically adjusted to represent an improved scenario. This allows us to observe how such changes can shift injury outcomes, particularly reductions in fatal and major injuries, providing actionable insights for data-driven safety interventions. The distinctive contribution of this research lies in moving from prediction to prevention. Rather than focusing primarily on comparing machine-learning models, this study develops a unified analytical pipeline that links predictive modeling with prevention-oriented simulation. Through this connection, the analysis quantifies how realistic improvements in behavioral and roadway-related factors can reduce the likelihood of fatal and serious injuries, offering a practical decision-support tool for policy makers.

Advances in natural language processing (NLP) and text-mining techniques present new opportunities for incorporating unstructured crash narratives descriptions written by police officers at the crash scene into injury-prediction models. These narratives provide rich qualitative insights not always reflected in structured datasets, potentially improving model performance and interpretability [

3,

4].

The present study integrates both structured crash data and crash narratives to develop predictive models for individual-level injury severity using machine-learning (ML) methods. In addition to evaluating the predictive accuracy of different model–text processing combinations, a central focus is to identify which input variables most strongly influence injury prediction. Random Forest is first applied after data cleaning to select the top 100 most important variables from over 350 available variables. The model is then developed on a subset of approximately 32,000 crash records from 2019 to 2023 in Kentucky, where individual-level injury severity is reported in police crash forms. The dataset is created by combining Kentucky police crash reports with detailed roadway and highway attributes from the Kentucky Highway Information System (HIS) database. Three ML models (Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and AdaBoost) are implemented and compared. To address the underrepresentation of fatal and major injuries, a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)-based oversampling strategy is applied to the training data before modeling.

The first aim of the modeling process is to identify the best-performing combination of ML algorithms and NLP techniques. Based on the results, the integration of TF-IDF with XGBoost achieves the highest prediction performance. Following model development, predictions are generated for a larger dataset of nearly 67,000 crashes, in which only the original 32,000 had known injury severity values. The results of this prediction served as a baseline. Next, a simulation-based sensitivity analysis is conducted by systematically adjusting individual variables (such as posted speed limits, restraint usage, and alcohol involvement) and re-running the predictions to evaluate changes in the distribution of injury severity [

5]. The target variable in this study includes four levels of individual injury severity reported in Kentucky police crash records: fatal, major injury, minor injury, and possible injury. These simulation results are intended to inform targeted interventions aimed at reducing the frequency of severe injuries and improving overall traffic safety.

2. Literature Review

Traffic crashes remain one of the leading causes of injury and death globally, and the US is no exception. To mitigate crash impact, researchers use predictive modeling techniques to better understand and prevent injuries. A substantial body of literature focuses on identifying key determinants of crash severity and developing predictive models to support transportation safety policies and decision-making. For an extensive review of related studies, readers may refer to [

6,

7]. Traditional statistical models, such as multinomial logit and ordered probit, have long been used to predict crash severity [

8]. However, these approaches often rely on restrictive assumptions and struggle to capture complex, nonlinear interactions among variables. To overcome these limitations, machine learning (ML) techniques such as Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and AdaBoost have gained popularity due to their ability to handle high-dimensional data, nonlinearity, and variable interactions [

9]. Recent studies confirm that ML approaches can outperform traditional statistical models while also highlighting explanatory factors behind injury outcomes [

10].

Historically, injury severity prediction has been conducted at the crash level, where a single severity label is assigned to the entire crash based on the most severe outcome among all individuals involved. Although practical, this method overlooks the common occurrence of multiple occupant injuries within the same crash. More recent work has shifted toward individual-level prediction to better account for personal and situational differences [

11]. Furthermore, research has emphasized the importance of roadway classification and contextual heterogeneity (e.g., interstate vs. rural two-lane roads), showing that crash factors may vary substantially by roadway type [

12,

13]. Another emerging theme of research leverages unstructured data, e.g., crash narratives. Police officers’ written descriptions of crash events often contain behavioral and situational details that coded datasets may not adequately capture. NLP methods such as TF-IDF and Word2Vec have shown promise in extracting meaningful information from these narratives, including driver behavior, vehicle control, and ejection or entrapment events, all of which are linked to heightened injury risks [

14]. Beyond these approaches, hybrid methods such as integrating structural equation modeling with neural networks have also been used to uncover latent crash factors, illustrating how combining modeling paradigms can improve explanatory power [

15].

A further focus in the literature is identifying actionable variables that can meaningfully shift injury severity outcomes. Sensitivity analysis and simulation-based analysis have emerged as practical tools to evaluate how changes in key variables can alter predicted outcomes [

16]. These approaches allow researchers to test the potential safety benefits of interventions such as increasing seatbelt use or reducing alcohol involvement. Despite the growing number of ML-based severity prediction studies, relatively few have made variable sensitivity a central focus. Recent work using Bayesian network modeling demonstrates how sensitivity analysis can reveal the role of demographic and roadway factors in shaping crash outcomes [

1]. Previous studies applying Bayesian network analysis have demonstrated its strength in capturing probabilistic dependencies among crash-related variables and quantifying the influence of both observed and latent factors on injury severity. For instance, Al Sulaie (2025) [

1] found that Bayesian models effectively identify conditional relationships between roadway geometry, environmental conditions, and driver demographics, providing a transparent interpretation of how variable interactions contribute to crash consequences. Such probabilistic frameworks complement deterministic machine-learning approaches by offering uncertainty quantification and clearer causal inference, reinforcing the importance of sensitivity-based analyses in crash-severity modeling. This is important because identifying which variables offer the greatest potential for reducing severe outcomes can guide targeted interventions. Restraint use, for example, has consistently been linked to reductions in serious injuries and fatalities [

17], and similar findings emerge in international studies showing the strong influence of road type, vehicle type, and collision type on severity outcomes [

6,

18].

Finally, to improve both accuracy and fairness in severity prediction, researchers must address the class imbalance common in crash datasets. Severe injury cases such as fatalities and major injuries are typically underrepresented compared to minor or possible injuries. This imbalance often biases models toward predicting majority classes while failing to detect rare but high-impact outcomes. To counter this, recent studies have incorporated oversampling techniques [

19], particularly Synthetic Minority Oversampling Techniques (SMOTE) and its K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)-based variations, which improve the balance of training data and enhance model generalization across severity levels. These methods have shown promise in improving performance for minority classes.

Collectively, advances in data balancing, text mining, and simulation underscore the evolving role of machine learning in transportation safety research not only as a tool for prediction, but as a framework for generating deeper insights [

20]. Building on this foundation, our study leverages both balanced ML training and NLP-enhanced inputs to predict injury severity and conduct systematic variable sensitivity analysis. This combined strategy provides a strong basis for identifying which factors most significantly shift injury outcomes and for informing more effective and targeted safety interventions.

Despite considerable progress in crash-severity modeling, the existing literature still faces several methodological limitations. Many studies rely solely on structured data, overlook individual-level variations, and give limited attention to data imbalance and feature selection challenges that affect model fairness and generalization. Additionally, sensitivity analyses are often restricted to descriptive interpretations rather than being extended to evaluate the potential effect of real-world interventions. The present study addresses these limitations collectively by combining structured and narrative data, applying feature selection and data balancing methods to improve model reliability, and implementing simulation-based sensitivity analysis to explore how modifying key variables could meaningfully influence injury outcomes.

3. Data

Reliable research begins with accurate data collection and careful preparation. Inconsistent records, missing values, or poorly merged datasets can significantly undermine the validity of any analysis [

21]. Given the complexity of integrating diverse sources and formats, this study places strong emphasis on thorough data preparation and preprocessing to ensure the integrity of the modeling results.

The primary data for this research come from two key sources: the Kentucky Highway Information System (HIS) and the official crash records maintained by the Kentucky State Police (KSP). HIS is a comprehensive repository of roadway data in Kentucky, systematically categorized into eight main sections and over thirty detailed subgroups. Each subgroup is organized using route-specific identifiers Route ID (RT_ID), Beginning Mile Point (BMP), and Ending Mile Point (EMP), and contains roadway attributes such as posted speed limits, average annual daily traffic (AADT), number of lanes, median types, and functional classifications. For this study, fifteen subgroups are selected for their relevance to roadway geometry and traffic flow, including functional classification, lane configuration, median and shoulder characteristics, curvature and grade information, intersection density, access control, pavement condition, AADT, truck percentage, and other geometric and operational descriptors. These HIS datasets are spatially integrated into a unified statewide database using RT_ID, BMP, and EMP as joining keys, enabling a detailed characterization of Kentucky’s roadway infrastructure.

The second major data source was the KSP crash database, which includes detailed records of all officially reported motor vehicle crashes. This study uses a five-year period from 2019 to 2023. The crash dataset is organized into six main components: (1) general crash-level information, (2) vehicle-level details, (3) person-level records, (4) environmental conditions, (5) vehicle attributes, and (6) driver-related characteristics. For each year, data from these components are collected, and merged to construct a unified person-level dataset. The raw crash dataset contained about 1.2 million person-level records across the five-year period. After data cleaning, excluding incomplete entries, and aligning with HIS roadway attributes, the final dataset used for modeling consists of roughly 32,000 labeled records with known injury severity and an additional 35,000 unlabeled records, for a total of about 67,000 records.

Given this study’s focus on individual-level injury prediction, and since the lowest level of information is individual-based, we create our dataset at the individual level. Injury severity is classified into four levels: Fatal, Serious Injury, Minor Injury, and Possible Injury. Although “No Injury” cases are not explicitly recorded at the person level, an attempt is made to infer them by including individuals from crashes labeled as Property Damage Only (O). However, this introduces noise and reduces model performance, so the final dataset excludes the “No Injury” category and focuses solely on the four explicitly reported severity levels. Following preparation, the cleaned crash dataset spatially joined with the HIS database using RT_ID, BMP, EMP, and the specific Mile Point of each crash to ensure accurate alignment between crash records and roadway attributes. The merged dataset is then validated to resolve redundancies and inconsistencies. In the final integration step, the structured dataset is enriched with unstructured crash narratives. These narratives, written by police officers at the scene, contain descriptive details about crash sequences, contributing factors, driver behaviors, and roadway or environmental conditions information often missing from structured fields. Narratives are available for more than 90% of cases and range from short notes to multi-paragraph descriptions. To prepare the dataset for machine learning, categorical features are encoded into numerical or binary formats. The finalized dataset contains 92 core features and more than 350 derived sub-features. A summary of some variables used in modeling is provided in

Table 1. All infrastructure-related attributes from HIS (e.g., lane/shoulder/median, curvature/grade, access control, pavement indicators, speed limits, AADT, functional class) were retained and entered the modeling pipeline together with person/vehicle/environment fields.

Table 1 summarizes only a subset for brevity; the full modeling used 350 + features.

4. Methodology

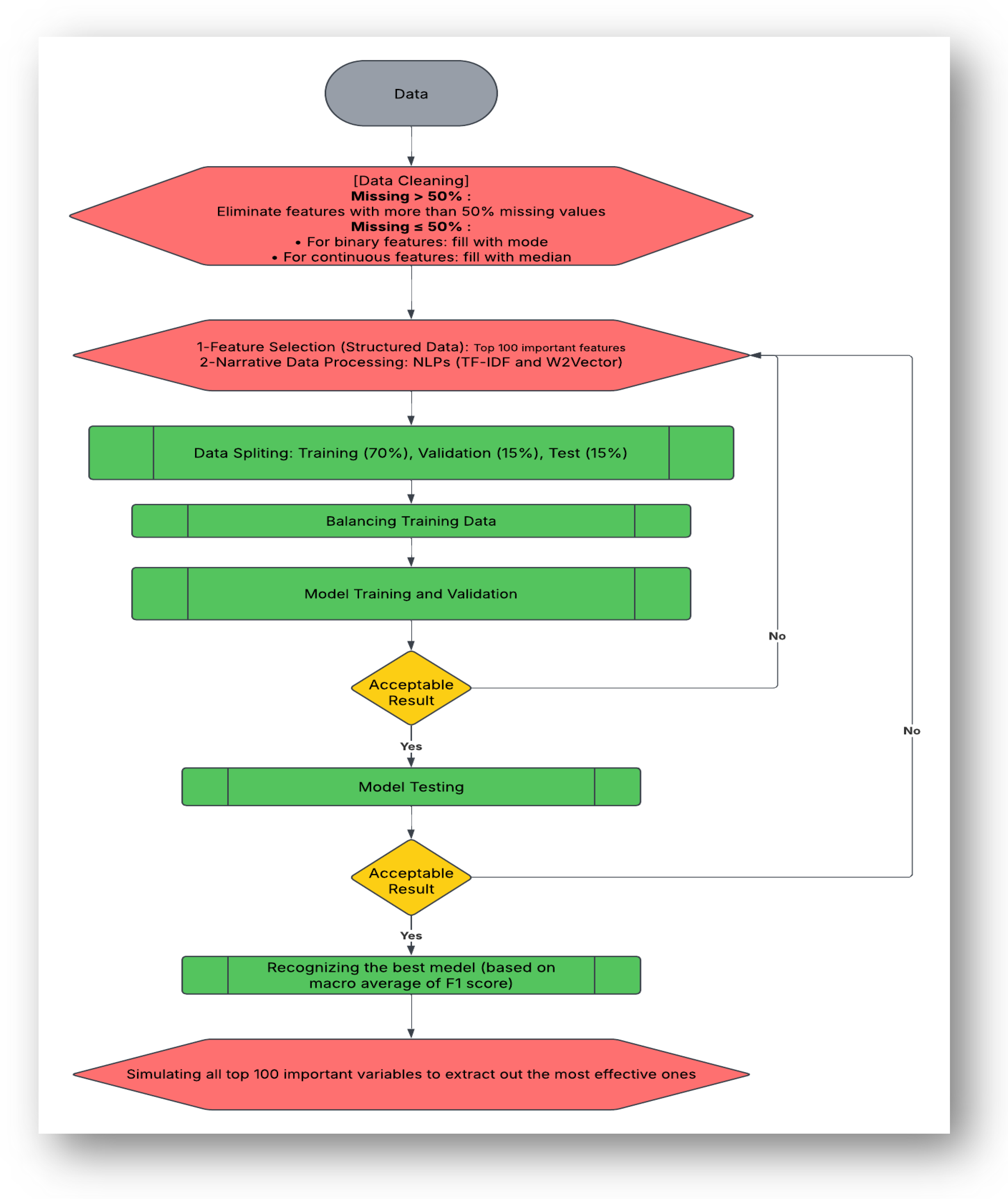

This study adopts a structured methodology to develop and evaluate injury-severity prediction models by integrating both structured crash data and unstructured police narrative texts. To provide transparency and facilitate reproducibility, the overall workflow is illustrated in

Figure 1, beginning with data integration and cleaning, followed by feature selection, class balancing, model training and tuning, validation, and finally sensitivity analysis. The process begins with careful preparation of the structured variables. Categorical attributes such as crash type, roadway functional class, and vehicle type are converted into numerical or binary codes so that they can be used in machine-learning models. Real-world datasets, especially those derived from crash reports, often contain missing values due to factors such as incomplete data entry, reporting errors, or unavailable information during incident documentation. Managing missing data effectively is critical, as it can substantially influence model accuracy and reliability [

22]. In this study, a two-pronged approach is adopted to address this issue: 1—Features with more than 50% missing values were excluded from the analysis, as previous work has shown that large proportions of missing attributes (up to approximately 50%) in crash-injury datasets can degrade model stability and interpretability [

23,

24], and 2—the remaining missing values are imputed using the mode for binary (categorical) variables and the median for continuous (numerical) variables. This strategy helps preserve valuable information while maintaining the robustness of the dataset for machine learning applications [

25,

26].

For unstructured crash narratives, natural language-processing techniques are applied. Each narrative is preprocessed through tokenization, stop-word removal, and lemmatization. Two methods are then used to convert the narratives into numerical features: Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF), which captures the importance of words, and Word2Vec, which represents the semantic meaning of words based on their context. These textual features are combined with the structured dataset to provide a more comprehensive picture of crash conditions.

To ensure reliable model development and to avoid overfitting, the dataset (32,000 records) is divided into three subsets: training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%). The split is performed using stratified random sampling with a fixed random seed to preserve the proportional distribution of injury-severity classes across all subsets. Several partition ratios are tested during hyperparameter tuning, and the 70/15/15 division consistently provides the most stable and accurate results. The training set is used to teach the model, while the validation set supports hyperparameter tuning and model selection without introducing bias. The test set, kept entirely separate, is used once for final performance evaluation. Stratified sampling preserves the distribution of injury-severity classes across all subsets. This three-way split prevents data leakage, ensures fair model assessment, and improves generalization to new data. It also enables iterative tuning while maintaining evaluation integrity, thereby enhancing the model’s real-world applicability [

27].

To address the imbalance in injury-severity outcomes where fatal and serious injuries are much less frequent, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) with a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) approach is applied only to the training data. This ensures that the models have a more balanced exposure to different severity classes during training while leaving the validation and test sets unchanged to reflect real-world distributions [

28,

29]. Feature selection is performed on the structured data using a Random Forest model. Importance scores are calculated for all features, and the top 100 are retained to reduce complexity and focus on the most influential variables [

20]. These selected features, together with the narrative-based variables, form the input space for model training. Three machine-learning algorithms (Random Forest, AdaBoost, and XGBoost) are used to develop prediction models. During model development, tuning of key settings is carried out to improve performance. For example, in Random Forest the number of trees is adjusted; in AdaBoost the number of iterations and the learning speed are varied; and in XGBoost the tree depth and learning rate are tuned. These adjustments help each model perform more effectively without overfitting. After evaluation, the combination of XGBoost with TF-IDF features achieves the best results. To avoid overfitting, the labeled dataset of 32,000 records is used only for training, validation, and testing, and all performance results are calculated only on the test set, which is kept separate from training and validation. This ensures that the reported metrics reflect the model’s performance on unseen data and are not inflated by information the model has already learned from. Once the final model is selected, it is applied to the entire dataset of about 67,000 records. Predictions for the 32,000 labeled cases are compared against observed values to check consistency and then combined with predictions for the ~35,000 unlabeled records. The full set of 67,000 predictions is used as the basis for the subsequent variable sensitivity analysis. Finally, a simulation-based sensitivity analysis is performed to examine how changes in specific crash-related factors can shift injury-severity outcomes. Key variables such as speed limits, restraint use, roadway departure, alcohol involvement, ejection, and entrapment are systematically modified to represent ideal conditions, and the resulting predictions are compared against baseline outcomes.

4.1. Feature Selection

Feature selection is the process of ranking and choosing the most informative predictors from a large set of variables to enhance model accuracy, prevent overfitting, and simplify interpretation. This is critical when working with high-dimensional datasets, as it reduces complexity, minimizes overfitting, improves interpretability, and speeds up training [

30]. In this study, Random Forest’s built-in feature importance scores are used to identify and retain the most relevant predictors [

31]. Feature importance is determined by how much each variable reduces classification uncertainty (measured through impurity) across all trees in the model. By ranking variables according to these scores, the analysis reveals that keeping the top 100 features provides the best balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. Random Forest is chosen for this task because of its ability to handle multicollinearity and capture non-linear interactions, making it particularly effective for selecting meaningful variables. The selected features are then applied consistently across all machine-learning models, ensuring both comparability and generalization [

32,

33].

4.2. ML Models

4.2.1. Random Forest (RF)

Random Forest, introduced by Breiman (2001), is a widely used ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their predictions to improve stability and accuracy. By training each tree on a bootstrapped sample of the data and using random subsets of features at each split, RF reduces overfitting and captures complex interactions between variables. It is robust to noise, handles high-dimensional datasets effectively, and provides built-in measures of feature importance, making it valuable for both prediction and variable selection [

20,

34].

4.2.2. Adaptive Boosting

AdaBoost, developed by Freund and Schapire (1997) [

35], is a boosting algorithm that combines many weak learners, typically small decision trees into a stronger classifier. The method works by placing higher weights on misclassified samples at each iteration, forcing subsequent learners to focus on the more difficult cases. Through this adaptive reweighting process, AdaBoost incrementally improves predictive performance. Its strength lies in its simplicity and ability to reduce bias while maintaining relatively low variance compared to single models [

36].

4.2.3. Extreme Gradient Boosting

XGBoost is an advanced implementation of gradient boosting that has gained popularity for its high accuracy and computational efficiency. It builds decision trees sequentially, with each new tree correcting the errors of the previous ones. Key improvements include the use of regularization to prevent overfitting, efficient handling of missing values, parallelized computation for large datasets, and a pruning strategy that refines trees to improve generalization. These features allow XGBoost to achieve strong predictive performance in both research and applied settings [

37].

Tree-based ensemble algorithms—Random Forest, AdaBoost, and XGBoost—were selected according to previous studies that have demonstrated their strong predictive ability on structured crash datasets and their robustness for heterogeneous tabular data. Other advanced techniques such as gradient boosting variants (e.g., LightGBM and CatBoost), neural networks, and deep-learning architectures were also reviewed in related research. However, given the size and structure of the available data and the focus on maintaining interpretability for transportation safety analysis, ensemble tree models were determined to be the most suitable and efficient choice for this study [

38,

39].

4.3. Text Mining Techniques

4.3.1. TF-IDF

TF-IDF is a text-mining technique that transforms narrative text into numerical features by measuring how important a word is in a document relative to the overall dataset. Words that appear frequently in a single crash report but are less common across all reports are assigned higher weights, making them more informative for distinguishing patterns. This approach captures context-specific details such as “ejection,” “skid,” or “alcohol” that may strongly relate to injury severity while filtering out common, less useful words [

40].

4.3.2. Word2Vec

Word2Vec is a neural embedding method that represents words as dense vectors in a continuous space based on their co-occurrence in text. Unlike TF-IDF, which treats words independently, Word2Vec captures semantic and contextual relationships between words. For example, terms like “speeding” and “reckless driving” may be placed close together in the vector space, reflecting their similar meaning. This allows the model to leverage subtle behavioral and situational details from police narratives, improving the depth of crash severity prediction [

41].

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

Because crash severity data are highly imbalanced, relying only on accuracy can be misleading, as it favors majority classes while underestimating performance on rare but critical outcomes such as fatalities. To address this, the evaluation considered precision, recall, and their harmonic mean, the F1-score, which together capture both the ability to detect severe cases and the risk of false alarms. Among these, macro-F1 was adopted as the primary evaluation metric because it treats all severity levels equally, ensuring that minority classes such as fatal and serious injuries were given the same importance as more common outcomes. Weighted (micro) F1-scores were also reported to reflect performance relative to the actual distribution of injuries, while overall accuracy was included only as a secondary measure to provide a broad sense of correctness [

11].

This evaluation strategy aligns with best practices in imbalanced classification research, where macro-F1 has been widely recommended as a fairer indicator of balanced predictive ability. As noted by Saito and Rehmsmeier (2015), precision–recall and F1-based measures provide more informative insight than accuracy or ROC curves when dealing with skewed datasets, making them particularly relevant in traffic safety studies where severe injuries are rare but of highest concern. By focusing on macro-F1 while also reporting weighted F1 and accuracy, this study provides a robust and transparent assessment of model performance under realistic data conditions [

42].

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of integrating machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP) techniques for injury severity prediction, followed by a sensitivity analysis of the most influential variables. In total, nine models are developed by combining three ML algorithms with two NLP methods.

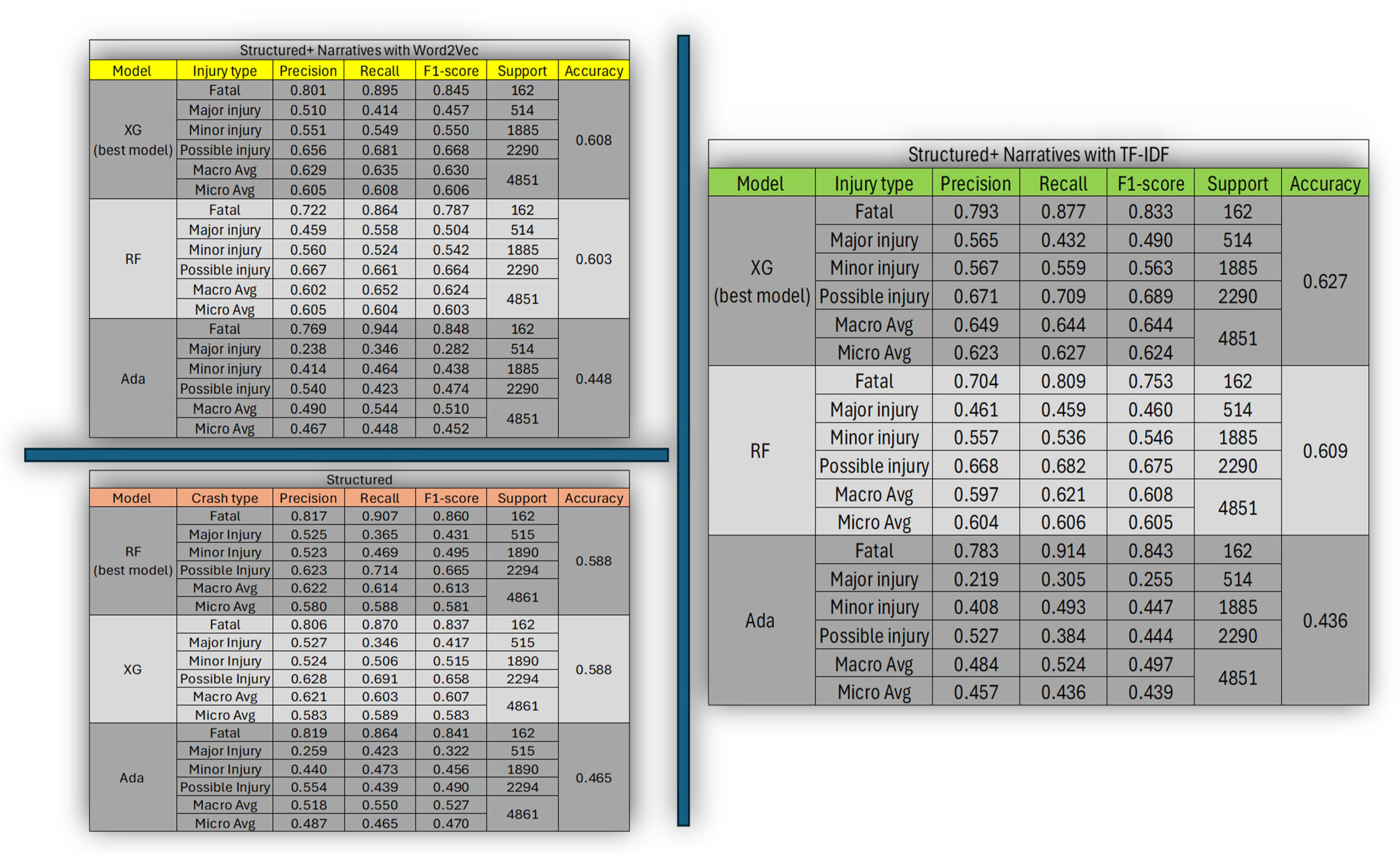

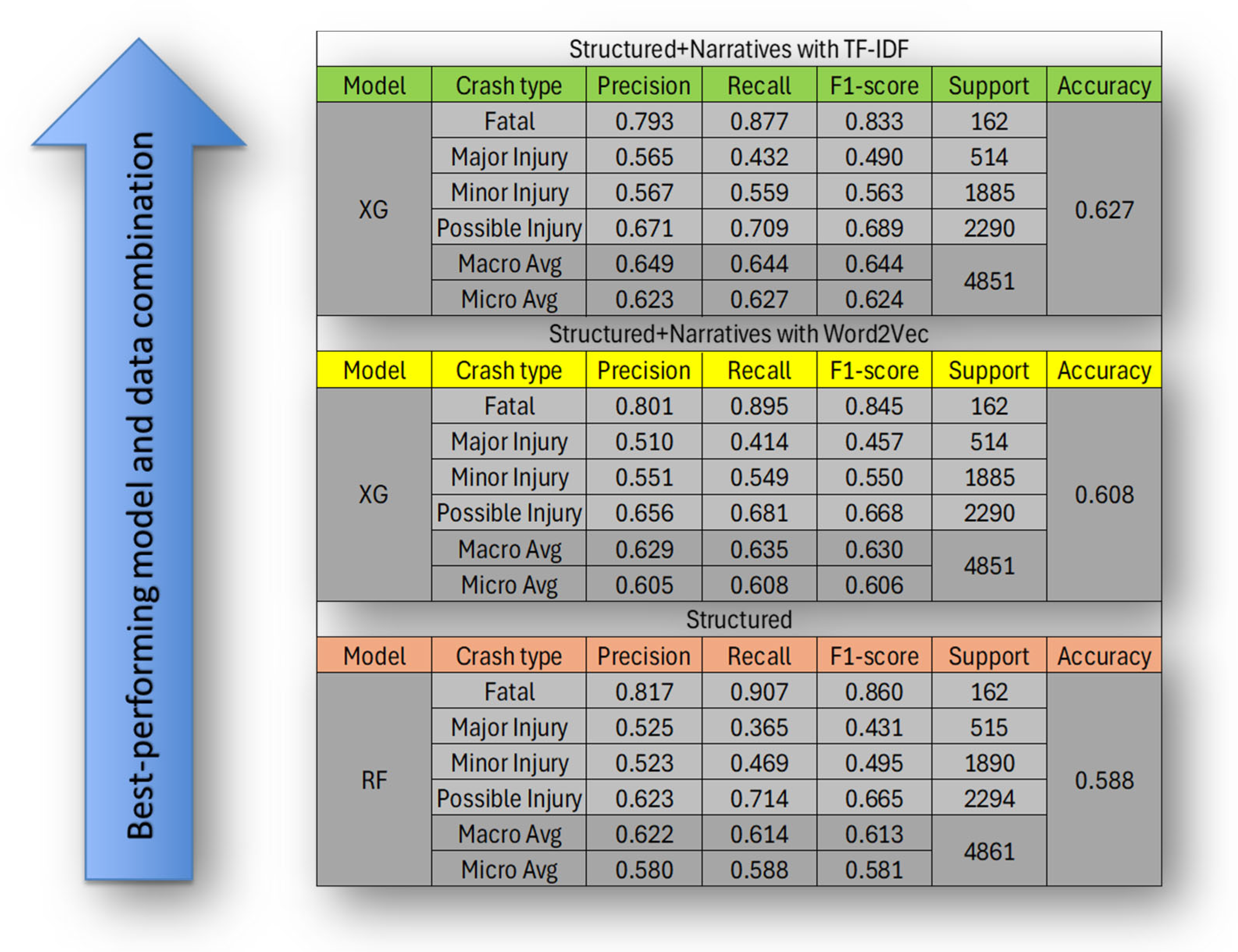

Figure 2 provides a complete comparison across all models, while

Figure 3 highlights the best performing configurations that are selected for further analysis.

As shown in

Figure 2, the modeling process begins with structured crash data only, without narrative features. Among these models, Random Forest (RF) achieves the highest performance. When narrative information is added through TF-IDF and Word2Vec, XGBoost consistently outperforms both RF and AdaBoost. Specifically,

Figure 3 shows that RF with structured data only achieves a macro-F1 of 0.613, XGBoost with structured + Word2Vec achieves 0.630, and XGBoost with structured + TF-IDF achieves 0.644. The latter configuration yields the best overall performance and is therefore selected for the sensitivity analysis. Model selection is based on macro-average F1-scores rather than accuracy, since accuracy alone can mask poor performance on rare but critical outcomes. In this study, SMOTE oversampling is applied only to the training set, while validation and test sets remain imbalanced to reflect real-world crash distributions. This approach ensures balanced learning while preserving realistic evaluation. Macro-F1, which gives equal weight to all severity levels, is the most appropriate metric for this context. While micro-F1 and per-class F1-scores are also reviewed, macro-F1 best captures balanced predictive performance across injury outcomes. Although macro-F1 values in the 0.61–0.64 range may seem modest, they are typical for crash-severity prediction tasks with highly imbalanced, noisy, and heterogeneous real-world data. More importantly, the inclusion of narrative features consistently improves performance compared to structured data alone. The consistent gains observed, particularly with XGBoost + TF-IDF, demonstrate the added value of unstructured police reports for enhancing injury-severity prediction. Furthermore, since this study employs a three-way data split (training, validation, and a fully unseen test set), the reported results provide a more reliable estimate of real-world model performance than approaches that rely solely on cross-validation or train/test splits. The comparative results also revealed that TF-IDF features outperformed Word2Vec embeddings. This outcome is consistent with prior domain-specific NLP findings showing that frequency-based representations are more effective when narrative texts are short, technical, and context-limited, as in police crash reports. Word2Vec generally requires larger and linguistically diverse corpora to capture semantic relationships, whereas TF-IDF preserves the most discriminative terms related to crash events such as “ejection,” “skid,” or “alcohol.”

After identifying the best-performing model (XGBoost with TF-IDF), the next step is to apply it to a larger dataset of over 67,000 records to generate injury-severity predictions. These results serve as the baseline scenario for comparison. The third phase of analysis then focuses on the most influential variables affecting crash severity. Using Random Forest feature importance, the top 100 predictors are identified, from which 11 variables demonstrate the most substantial effects in simulation-based sensitivity analysis.

Table 2 summarizes these variables, showing their prevalence in the dataset, predicted outcomes under simulation, and the baseline values for reference. The first simulation examines posted speed limits on rural two-lane (R2L) highways, which account for a disproportionate share of severe crashes in Kentucky approximately 40% of all crashes, 47% of injury-related crashes, and 66% of fatal crashes [

43,

44]. Because more than 85% of R2L segments in the dataset have limits of 50–55 mph (representing 29% of the full dataset), a scenario is simulated where all are reduced to 45 mph. The results indicate reductions in major and minor injuries, with a corresponding increase in possible injuries, suggesting an overall shift toward less severe outcomes. A second simulation evaluated the impact of raising speed limits by 5 mph, which instead produces a shift from possible injuries to minor injuries.

The next variables examined are impairment (R3) and roadway departure (R4). Simulating an ideal condition of no roadway departure produces a notable reduction in both major and minor injuries, while removing impairment also lowers the number of major injuries despite its smaller share in the dataset. Helmet non-use is another variable tested; although only 1.7% of individuals in the dataset are unhelmeted, simulating universal helmet use leads to a meaningful reduction in major injuries. Fatalities remain unchanged, likely due to the very small number (0.14%) of fatal cases involving unhelmeted motorcyclists and bicyclists. Behavioral factors such as alcohol involvement (R6) and speeding (R7) also show substantial effects. Simulating conditions where neither occurs produces notable reductions in fatalities, major injuries, and minor injuries, with increases in possible injuries. These results underscore the critical role of driver behavior in shaping injury-severity outcomes. Occupant ejection (R8) is another influential variable, with simulations showing significant reductions in fatalities and major injuries when ejections are eliminated. These findings emphasize the importance of seatbelt compliance, advanced restraint technologies, and vehicle-design improvements. Similarly, a broader driver impairment indicator (R9) that includes fatigue, drugs, and medical conditions also shows consistent reductions across severity levels under simulated improvements. The final two variables seatbelt non-use (R10) and vehicle entrapment (R11) produces the largest reductions in fatal and major injuries. If all unbelted occupants wear seatbelts, 94 fatalities and 195 major injuries can be prevented. Eliminating post-crash entrapment yields an even greater reduction: 110 fewer fatalities and 621 fewer major injuries. These results strongly reinforce the life-saving value of seatbelt use and highlight entrapment as a critical but under-addressed factor. Entrapment findings suggest two practical avenues: (i) improving vehicle safety design to reduce the risk of entrapment and (ii) enhancing emergency response to shorten the time to medical care. Entrapment was interpreted as a post-crash condition rather than a pre-crash causal variable. Therefore, the “No Entrapment” simulation should not be viewed as a behavioral or roadway-based prevention measure but as a hypothetical scenario for improving post-crash outcomes. In practical terms, this result can be interpreted as the potential safety benefit of faster emergency response, improved rescue accessibility, or vehicle design modifications that reduce the likelihood or duration of occupant entrapment. This distinction helps separate variables that influence crash occurrence or severity before impact (e.g., speed, restraint use, impairment) from those that influence injury consequences after the crash has occurred. In this study, prioritization of variables is based primarily on reductions in fatal injuries, reflecting the critical importance of preventing loss of life. However, other approaches could also be considered, such as weighting changes by societal costs or by total injury burden. These alternatives may provide additional insight into prioritization strategies for policy and resource allocation. Comparative studies have evaluated different machine-learning techniques for crash-severity modeling and upheld the practical advantage of ensemble tree methods. For example, the study by Daoud et al. (2025) compared seven algorithms including Random Forest, XGBoost and LSTM in nighttime crash severity prediction, demonstrating superior performance by tree-based learners [

45]. Similarly, the works by [

46,

47] reinforced this trend across different crash contexts and highlight the need for interpretable yet robust models in safety applications. From a policy adaptation perspective, such comparative insights enable transportation agencies to simulate intervention scenarios, prioritize countermeasures, and integrate model-driven guidance into safety management frameworks, such as increasing restraint use, reducing impairment, and improving roadway geometry or operational controls.

6. Conclusions

This study develops a comprehensive framework for predicting individual-level injury severity in traffic crashes by integrating structured roadway and crash data with unstructured police narratives using machine learning and NLP techniques. Among nine tested models, XGBoost combined with TF-IDF achieves the highest performance, demonstrating the added value of narrative data for improving predictive accuracy. Beyond prediction, the study advances prior sensitivity analyses by explicitly simulating how changes to key variables alter injury distributions. In doing so, it moves beyond crash-level associations to provide person-level insights that are both interpretable and actionable. Sensitivity analysis reveals that occupant entrapment, lack of seatbelt use, and impaired driver control are the most influential factors, with simulated improvements producing the largest shifts from fatal and major injuries toward less severe outcomes. These findings highlight clear opportunities for targeted interventions that can directly inform safety policy and practice. While alternative prioritization approaches such as weighting by societal cost or variable prevalence could be explored, this study focuses on reductions in fatal injuries, reflecting their paramount importance for safety policy. Notably, the integration of balancing techniques and NLP improves performance for rare injury classes, with the F1-score for fatal injuries increasing dramatically compared to previous studies from 0.13 [

48] to 0.83 in this study.

These results have direct implications for transportation safety management and program design. The approach outlined here offers a low-cost, implementable tool for policymakers and transportation agencies to evaluate the potential impact of safety interventions before deployment. By simulating changes to specific crash factors, decision-makers can prioritize strategies that yield the greatest benefits in injury reduction. Although the modeling framework considered all variables together within a unified sensitivity analysis, it is important to recognize that certain factors, such as entrapment and ejection, represent post-crash conditions rather than pre-crash causal elements. The interpretation of these results therefore emphasizes that such variables offer insights for improving vehicle design, rescue response, and post-crash management rather than for direct behavioral or roadway interventions. Future research should further compare model estimates with EMS and hospital injury data to enhance clinical validity and incorporate roadway heterogeneity such as freeway versus rural two-lane conditions to provide more context-sensitive insights. This research provides a hopeful foundation for linking predictive modeling with actionable, evidence-based safety improvements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z.M., R.S. and T.W.; methodology, M.Z.M., R.S. and T.W.; software, M.Z.M.; validation, M.Z.M., R.S. and T.W.; formal analysis, M.Z.M., R.S. and T.W.; data curation, M.Z.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.M.; writing—review and editing, M.Z.M., R.S. and T.W.; visualization, M.Z.M.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is derived from police crash reports that contain private and sensitive personal information; therefore, we are not eligible to share it publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Sulaie, S. Sensitivity analysis of factors affecting consequences due to traffic crashes: A Bayesian Network Modelling. J. Road Saf. 2025, 36, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.S.; Jalayer, M.; Das, S.; Kabir, M.A.B. Application of machine learning models and SHAP to examine crashes involving young drivers in New Jersey. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin, M.Z.F.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; Hasikin, K.; Abd Razak, N.A.; Omar, R. Contextualizing injury severity from occupational accident reports using an optimized deep learning prediction model. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.M. Characterizing accident narratives with word embeddings: Improving accuracy, richness, and generalizability. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 80, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, K.; Ibrahim, M. Analysis and identification of contributing factors of traffic crashes in New York City. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 55, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, H.; Ara, J.; Hasib, K.M.; Sourav, M.I.H.; Karim, F.B.; Sik-Lanyi, C.; Governatori, G.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Yasmin, S. Crash severity analysis and risk factors identification based on an alternate data source: A case study of developing country. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhipeng, P.; Yuan, R.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X. A comparative analysis of factors affecting injury severity in speeding-related crashes on rural and urban roads. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2024, 29, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Fan, W. Mixed logit models for examining pedestrian injury severities at intersection and non-intersection locations. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2022, 14, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Hossain, M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.M.I.; Ray, S.K. A comparative study of machine learning algorithms to predict road accident severity. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (IUCC/CIT/DSCI/SmartCNS), London, UK, 20–22 December 2021; pp. 390–397. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Z.; Yao, J.; Zou, X.; Pu, K.; Qin, W.; Li, W. Investigating Factors Influencing Crash Severity on Mountainous Two-Lane Roads: Machine Learning Versus Statistical Models. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qu, X.; Zhang, W.; Guo, W.; Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Chen, Y. Analyzing Crash Severity: Human Injury Severity Prediction Method Based on Transformer Model. Vehicles 2025, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhdari, M.; Kashani, A.T.; Amirifar, S.; Taheri, A.; Müller, G. Capturing Road-Level Heterogeneity in Crash Severity on Two-Lane Rural Highways: A Multilevel Mixed-Effects Approach. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.09941. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Chaozhe, J.; Adanu, E.K.; Jamal, A.; Almarhabi, Y.; Islam, M.K.; Al-Ahmadi, H.M. Assessing heterogeneity in factors influencing three-wheeled motorized rickshaws crash outcomes between weekdays and weekends. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Chen, S.; Yue, L.; Xu, Y.; Noyce, D.A. Analyzing relationships between latent topics in autonomous vehicle crash narratives and crash severity using natural language processing techniques and explainable XGBoost. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 203, 107605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Persaud, B. Investigating the influence of socioeconomic factors on the relationships between road characteristics and traffic crash frequency and severity--A hybrid structural equation modelling− artificial neural networks approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 218, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shiwakoti, N.; Xu, Y.; Ye, Z. Injury severity prediction and exploration of behavior-cause relationships in automotive crashes using natural language processing and extreme gradient boosting. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda Mbarga, N.; Abubakari, A.-R.; Aminde, L.N.; Morgan, A.R. Seatbelt use and risk of major injuries sustained by vehicle occupants during motor-vehicle crashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakib, N.; Paul, T.; Das, S.; Hossain, A. Exploring the factors affecting injury severity in highway and non-highway crashes in Bangladesh applying machine learning and SHAP. IATSS Res. 2025, 49, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, M.; Kına, E.; Rustam, F.; Villar, M.G.; Alvarado, E.S.; De La Torre Diez, I.; Ashraf, I. Data oversampling and imbalanced datasets: An investigation of performance for machine learning and feature engineering. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, M.Z.; Karimi, S.; Wang, T.; Kluger, R.; Souleyrette, R. Predicting person-level injury severity using crash narratives: A balanced approach with roadway classification and natural language process techniques. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.07845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarzadeh, M.; Rezaei, H.; Majidi, M.Z. a Pricing Model for Freeway Tolls Based on the Share of Mode Shift, Route Shift, Travel Time Change and Users’ Willingness to Pay (Case study: Tehran_Saveh Freeway). J. Transp. Res. 2022, 19, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, M.Z.; Rasaizadi, A.; Majidi, K.; Saffarzadeh, M. The effect of freeway toll pricing on travel mode changes, route changes, and departure time changes. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2024, 17, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagias, P.; Magoulas, G.D.; Prifti, Y.; Provetti, A. Predicting seriousness of injury in a traffic accident: A new imbalanced dataset and benchmark. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Applications of Neural Networks, Crete, Greece, 17–20 June 2022; pp. 412–423. [Google Scholar]

- Stekhoven, D.J.; Bühlmann, P. MissForest--non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, S.A.; Shah, S.L. Treatment of missing values in process data analysis. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 86, 838–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuna, E.; Rodriguez, C. The treatment of missing values and its effect on classifier accuracy. In Proceedings of the Classification, Clustering, and Data Mining Applications: Proceedings of the Meeting of the International Federation of Classification Societies (IFCS), Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–18 July 2004; pp. 639–647. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y. CPS-3WS: A critical pattern supported three-way sampling method for classifying class-overlapped imbalanced data. Inf. Sci. 2024, 676, 120835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, P.; Elangovan, G.; Ravichandran, K.; Shanmuganathan, V.; Pasupathi, S.; Chakrabarti, T.; Chakrabarti, P.; Margala, M. Robust diabetic prediction using ensemble machine learning models with synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadipour, F.; Mamdoohi, A.R.; Wulf-Holger, A. Impact of built environment on walking in the case of Tehran, Iran. J. Transp. Health 2021, 22, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Guleria, K.; Trivedi, N.K. Feature selection in machine learning: Methods and comparison. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), Greater Noida, India, 4–5 March 2021; pp. 789–795. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Tao, W.; Jing, Z.; Wang, P.; Jin, Y. Traffic accident duration prediction using multi-mode data and ensemble deep learning. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, H. Recent advances in feature selection and its applications. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2017, 53, 551–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, C.; Qi-Guang, M.; Jia-Chen, L.; Lin, G. Advance and prospects of AdaBoost algorithm. Acta Autom. Sin. 2013, 39, 745–758. [Google Scholar]

- Kavzoglu, T.; Teke, A. Predictive performances of ensemble machine learning algorithms in landslide susceptibility mapping using random forest, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) and natural gradient boosting (NGBoost). Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 7367–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamian, A.; Aghaei, A.A.; Cheng, Q. TabKAN: Advancing Tabular Data Analysis using Kolmogorov-Arnold Network. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.06559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azin, B.; Ewing, R.; Yang, W.; Promy, N.S.; Kalantari, H.A.; Tabassum, N. Urban Arterial Lane Width versus Speed and Crash Rates: A Comprehensive Study of Road Safety. Sustainability 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaydy, W.I.; Hashim, H.A.; Najm, Y.; Jalal, A.A. Document classification using term frequency-inverse document frequency and K-means clustering. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2022, 27, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. Evaluating Effect of Operating Speed on Crashes of Rural Two–Lane Highways. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 2882951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F. Incorporating Speed Into Crash Modeling for Rural Two-Lane Highways. Ph.D Thesis, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Daoud, R.; Vechione, M.; Gurbuz, O.; Sundaravadivel, P.; Tian, C. Comparison of Machine Learning Models to Predict Nighttime Crash Severity: A Case Study in Tyler, Texas, USA. Vehicles 2025, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezashoar, S.; Kashi, E.; Saeidi, S. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for predicting traffic accident severity (case study: United Kingdom from 2010 to 2014). Int. J. Crashworthiness 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffiee Haghshenas, S.; Guido, G.; Shaffiee Haghshenas, S.; Astarita, V. Predicting the level of road crash severity: A comparative analysis of logit model and machine learning models. Transp. Eng. 2025, 20, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, K.; Li, C. Crash injury severity prediction using an ordinal classification machine learning approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).