Methodology for Determining the Territories Where Scheduled Public Transport Should Be Changed to DRT

Abstract

1. Introduction

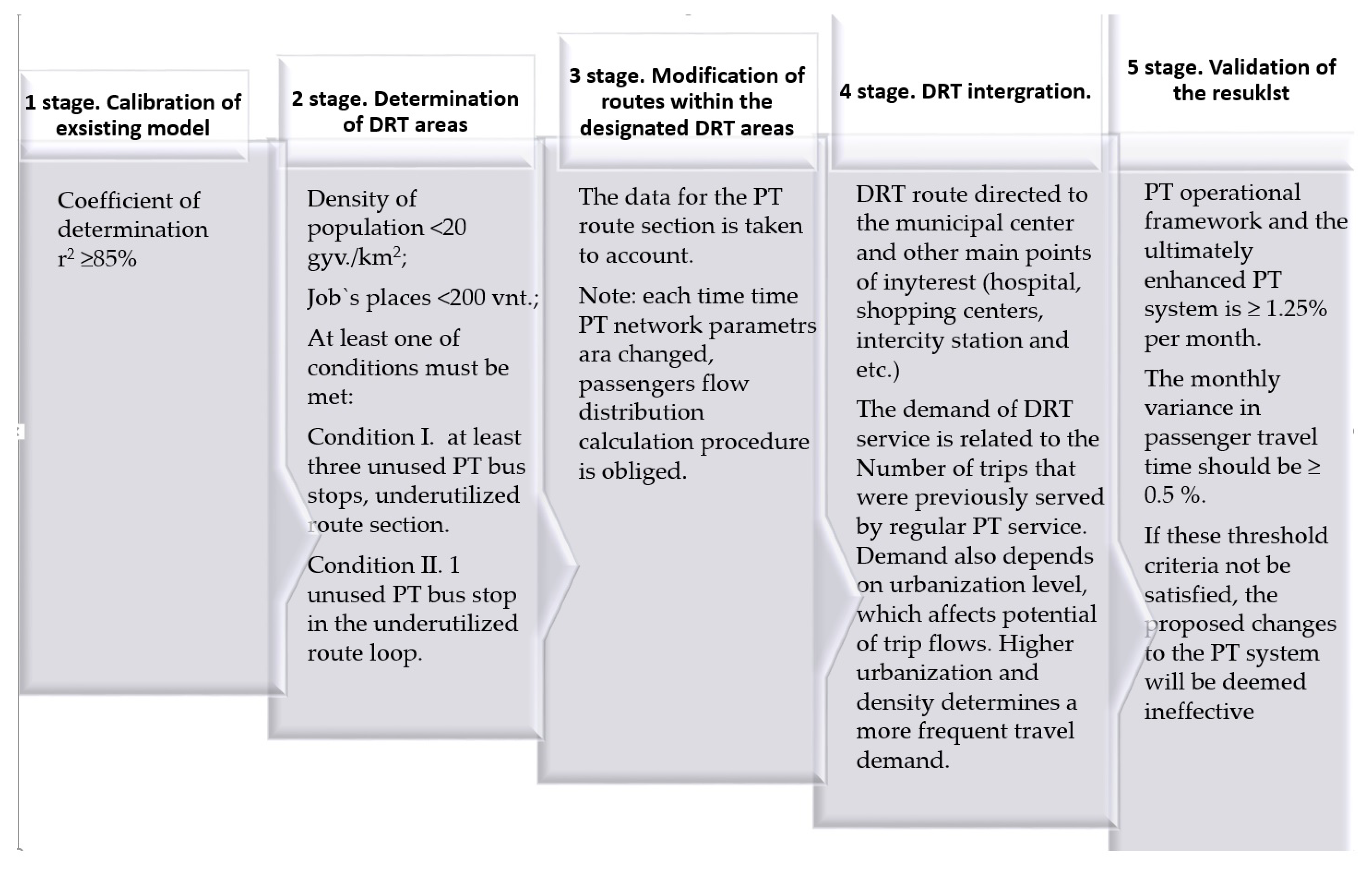

2. Methodology and Creation of the Model

- Identification of areas serviced by DRT (designated as DRT areas);

- Modification or elimination of routes within these DRT areas;

- Evaluation of the congruence between transport provision and the requirements of the local populace, with an estimation of the frequency of PT service provision in DRT areas;

- Subsequently, the improved PT system’s performance is compared to the existing model through metrics such as bus mileage and passenger travel time costs.

2.1. Model Building and Calibration

- The connectivity is not established over an extensive distance through the forest or across the river.

- Each existing PT stop is allocated a specific link.

- These links are systematically established between distinct zones.

- Furthermore, the link is delineated over a connector not exceeding 3 km.

2.2. Methodology for Changing the Type of Public Transport Organization

- (a)

- Population density is less than 20 inhabitants/km2;

- (b)

- The number of jobs is less than 200 in one place.

- Existing passenger flow data on PT routes. These data are more easily collected with an electronic ticket system and/or other permanent passenger counting tools.

- Road and street network data. These data are imported from existing information or planning systems, e.g., from GTFS data based on actual facts and adjusted according to the latest collected information.

- Current data on PT stops and routes (routes, directions, frequencies, and schedules). These data are imported from GTFS based on actual facts (such data are already collected in Lithuania [25] and updated according to official PT organizers’ information.

- Demographic (population) data, such as the number of children, schoolchildren, students, seniors, working residents, unemployed, etc. This information is available from the State Data Agency.

- Statistical data, such as the number of jobs, places in kindergartens, educational institutions, etc. This information is found according to the State Data Agency, available GIS platforms, etc.

- Modal distribution data, which are found in territorial planning documents (Master Plans, Sustainable Mobility Plans, etc.).

- Survey data of the region’s residents on the use of PT services (whether residents use the PT system, whether they are satisfied with it, reasons for not using it, what would encourage them to start using it, etc.).

- Results of the regression analysis of the criteria determining the region’s PT passenger flows.

- Unused bus stops—a bus stops where the number of passenger trips per month is 0.

- An underutilized section of a PT route is characterized by transporting no more than 20 passengers per working day.

- An underutilized route loop is an additional route branch ending at a single stop where the number of passengers transported is no more than 20 trips/working day.

- Condition I. There exists an underutilized route section when there are at least three unused PT bus stops in the DRT area.

- Or

- Condition II. There exists an underutilized route loop when there is one unused PT bus stop in the DRT area, which is reached by creating a route loop.

- In scenarios where route segments accommodating in excess of 50 passengers per month are eliminated, the DRT system within the specified area operates at a frequency of twice daily, contingent upon demand. This frequency of DRT operation is deemed sufficient to maintain fundamental connectivity with primary facilities and to provide convenient mobility options.

- Conversely, route segments with passenger volumes below 50 per month be excluded, the DRT service frequency is adjusted to twice monthly, again contingent upon demand. This bi-monthly service provision ensures that transport services are maintained within regions of low population density, thereby preventing excessive strain on the PT system. Furthermore, this approach facilitates social inclusion by guaranteeing access to essential services, notwithstanding the sparse passenger traffic.

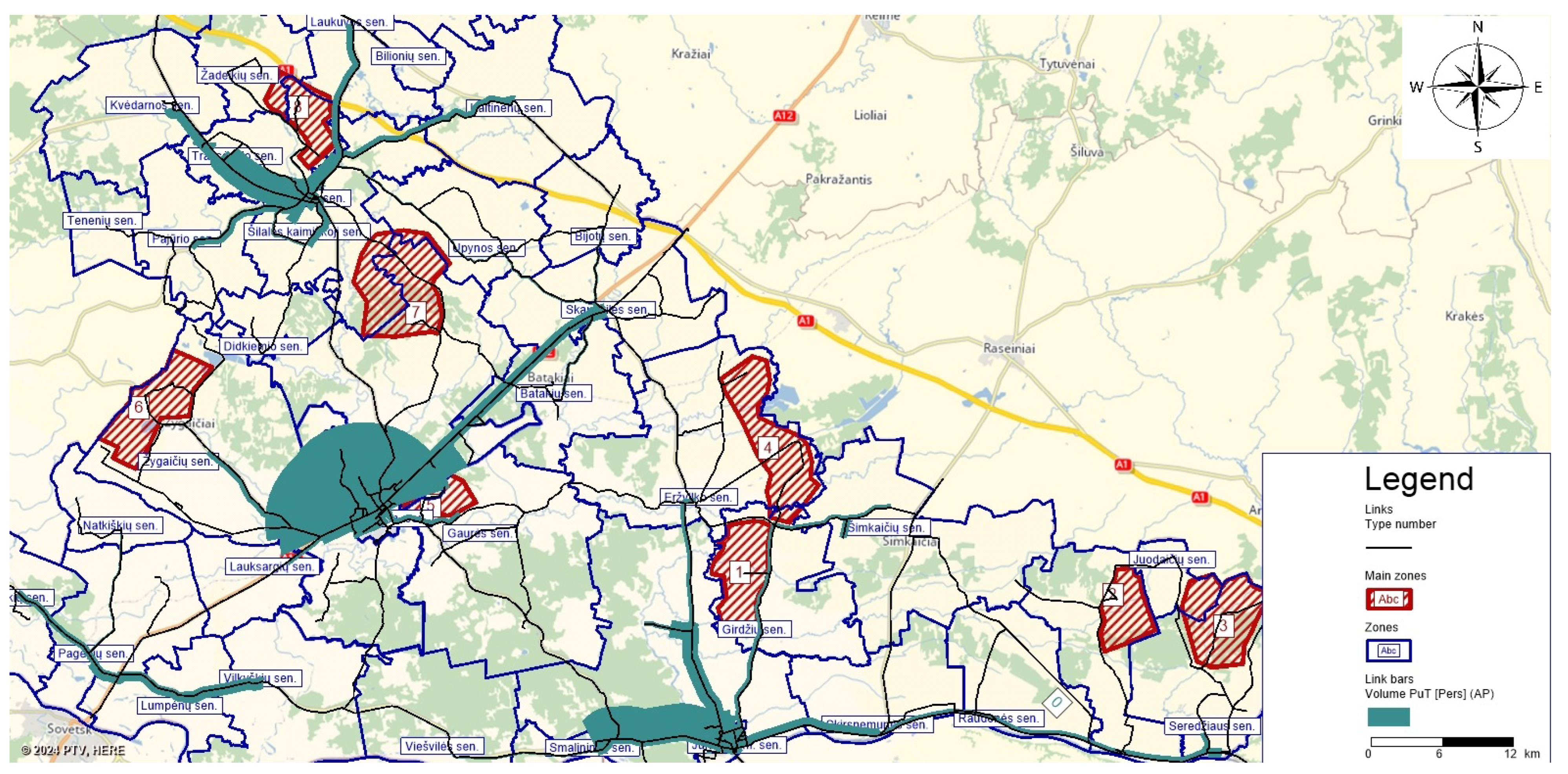

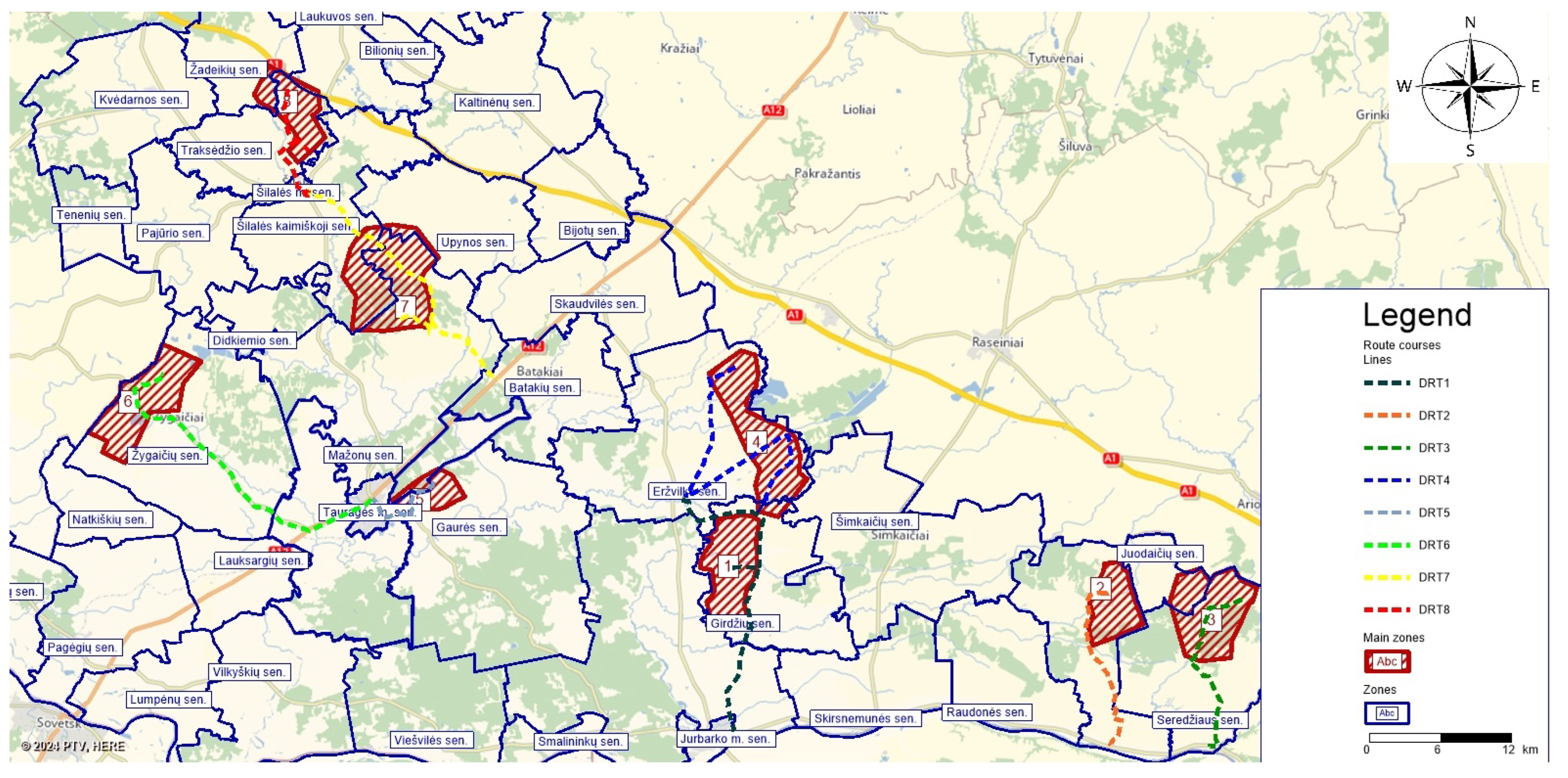

3. Results of Modeling the Provision of Regional Public Transport Services

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PT | Public transport |

| DRT | Demand-responsive transport |

| O-D | Origin-Destination (OD) matrix |

References

- Mugion, R.G.; Toni, M.; Raharjo, H.; Di Pietro, L.; Sebathu, S.P. Does the service quality of urban public transport enhance sustainable mobility? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1566–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Št’astná, M.; Vaishar, A.; Stonawská, K. Integrated Transport System of the South-Moravian Region and its impact on rural development. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 36, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, R.; Beecroft, M.; Nelson, J.D. On the role of frameworks and smart mobility in addressing the rural mobility problem. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin-Hawkins, B. Future Innovation for Rural Public Transport; National Innovation Centre Rural Enterprise: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Velaga, N.R.; Nelson, J.D.; Wright, S.D.; Farrington, J.H. The potential role of flexible transport services in enhancing rural public transport provision. J. Public Transp. 2012, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatskiv, I.; Budilovich, E.; Gromule, V. Accessibility to Riga public transport services for transit passengers. Procedia Eng. 2017, 187, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M.A.; Zefreh, M.M.; Torok, A. Public transport accessibility: A literature review. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2019, 47, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin-Hawkins, B. Demand Responsive Transport in Rural Areas: Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion, Monmouthshire & Pembrokeshire, Wales. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341939873_Demand_Responsive_Transport_in_Rural_Areas (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Avermann, N.; Schlüter, J. Determinants of customer satisfaction with a true door-to-door DRT service in rural Germany. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 32, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schasché, S.E.; Sposato, R.G. Systematic Literature Review of Demand-Responsive Transport Services. 2021. Available online: https://www.iaee.org/en/publications/proceedingsabstractpdf.aspx?id=17019 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Clewlow, R.R.; Mishra, G.S. Disruptive Transportation: The Adoption, Utilization, and Impacts of Ride-Hailing in the United States. 2017. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82w2z91j (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Kloth, H.; Mehler, S. Nachfragegesteuerte verkehre oder on-demand-ridepooling? Nahverkehr 2018, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schasché, S.E.; Sposato, R.G.; Hampl, N. User acceptance of demand-responsive transport services in rural areas: Applying the UTAUT to identify influential latent constructs. In Proceedings of the IEWT, Online, 8–10 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, L.; Sörensen, K. The On-Demand Bus Routing Problem: A Large Neighborhood Search Heuristic for a Dial-a-Ride Problem with Bus Station Assignment (No. 2020005). 2020. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ant/wpaper/2020005.html (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Tracks. The Future of Rural Bus Services in the UK. September 2020. Available online: https://bettertransport.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/legacy-files/research-files/The-Future-of-Rural-Bus-Services.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Bauchinger, L.; Reichenberger, A.; Goodwin-Hawkins, B.; Kobal, J.; Hrabar, M.; Oedl-Wieser, T. Developing Sustainable and Flexible Rural–Urban Connectivity through Complementary Mobility Services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R. Demand-Responsive and Sustainable Ways of (Public) Transport to Keep Shrinking Regions in Groningen Accessible. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Campisi, T.; Spadaro, C.; Russo, A.; Tesoriere, G.; Torrao, G. The Development of Integrated Public Transport and on Demand Services (PTs-DRTs) for Greater Flexibility and Complementarity of Transport Mode Choices. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Istanbul, Türkiye, 30 June–3 July 2025; pp. 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Caramuta, C.; Grosso, A.; Longo, G.; Ricchetti, C.; Rotaris, L. Design, implementation and monitoring of a Demand Responsive Transport service for student leisure transfers: The case study of University of Trieste. Transp. Eng. 2025, 20, 1003457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What It Is—Lazdijai Drive? (Kas yra Lazdijai veža?—In Lithuanian). Available online: https://lazdijaiveza.lt (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Camprisi, T.; Russo, A.; Spadaro, C.; Tiesoriere, G.; Torrao, G. Times Slot Choice Analysis for DRT Service: Evidence from Ragusa Province, Italy. 2025. Available online: https://www.archivesoftransport.com/index.php/aot/article/view/787/616 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Castillo, C.P.; Barranco, R.R.; Curtale, R.; Kompil, M.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Rodriguez, S.V.; Auteri, D. Are remote rural areas in Europe remarkable? Challenges and opportunities. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 105, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G. Rural electrification goes local: Recent innovations in renewable generation, energy efficiency, and grid modernization. IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2015, 3, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Statistics Portal of the Republic of Lithuania. Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/en (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Portal of Public Transport Routes in Lithuanian. Available online: https://www.visimarsrutai.lt/gtfs/ (accessed on 8 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ušpalytė-Vitkūnienė, R.; Samuilovas, A.; Ranceva, J. Methodology for Determining the Territories Where Scheduled Public Transport Should Be Changed to DRT. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040189

Ušpalytė-Vitkūnienė R, Samuilovas A, Ranceva J. Methodology for Determining the Territories Where Scheduled Public Transport Should Be Changed to DRT. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040189

Chicago/Turabian StyleUšpalytė-Vitkūnienė, Rasa, Andrius Samuilovas, and Justina Ranceva. 2025. "Methodology for Determining the Territories Where Scheduled Public Transport Should Be Changed to DRT" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040189

APA StyleUšpalytė-Vitkūnienė, R., Samuilovas, A., & Ranceva, J. (2025). Methodology for Determining the Territories Where Scheduled Public Transport Should Be Changed to DRT. Future Transportation, 5(4), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040189