Regulatory Enablers and Stakeholders’ Acceptance in Defining Eco-Friendly Vehicle Logistics Solutions for Rome

Abstract

1. Introduction

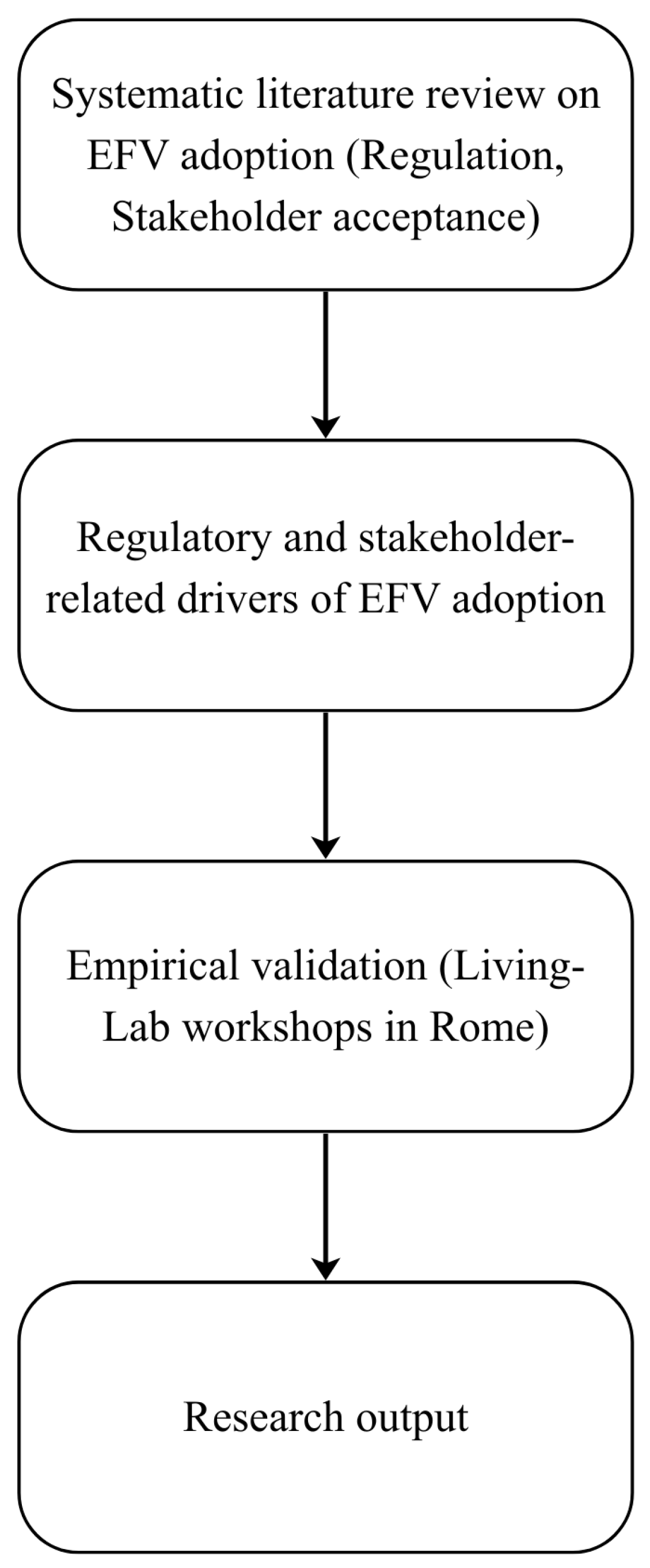

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

- (1)

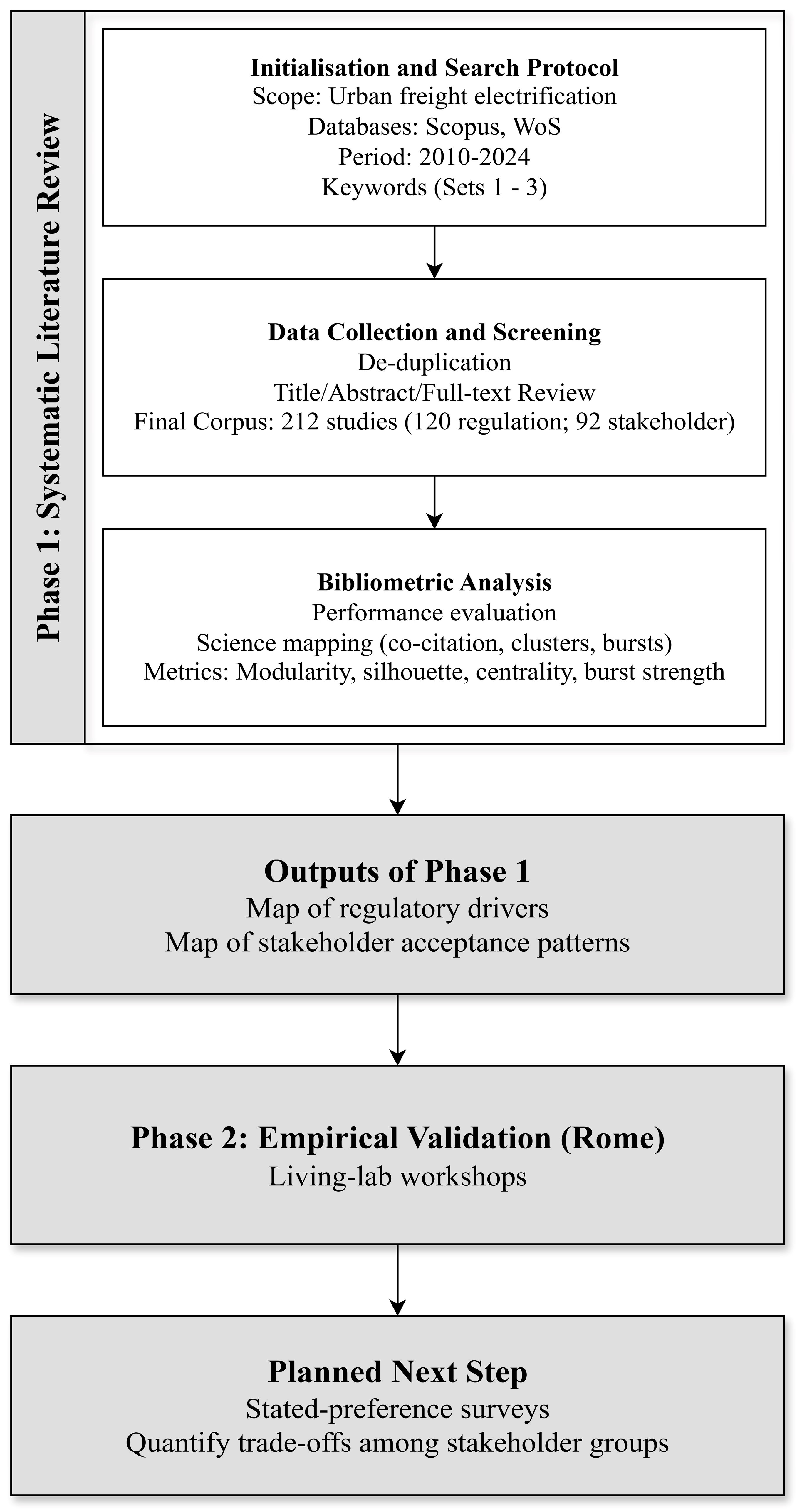

- Initialisation and Search Protocol: During the initialisation stage, the scope of the review was defined as urban freight electrification, and the search protocol was established. Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters published in English between 2010 and 2024 were retrieved from the Scopus and Web of Science databases. The search strategy combined three sets of keyword strings. The first set delineated the domain of application (urban freight and logistics), while the second set targeted eco-friendly vehicles. The third set was divided into two dimensions: one addressing regulation and the other focusing on stakeholders’ acceptance.

- (2)

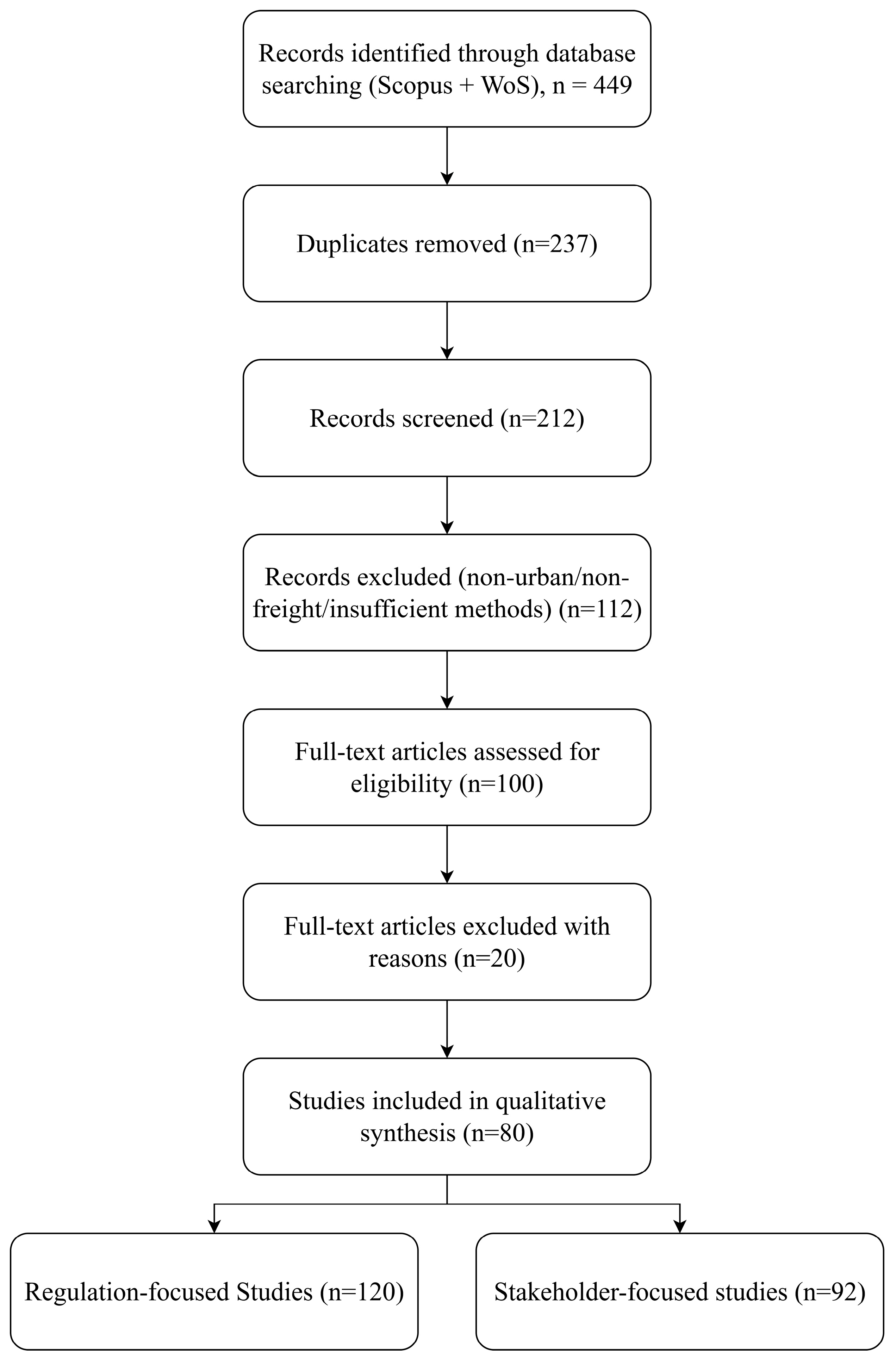

- Data Collection and Screening: The second stage of the review involved applying PRISMA’s identification, eligibility, and inclusion filters. Records were de-duplicated, and titles, abstracts, and, where necessary, full texts were assessed for relevance, resulting in a final corpus of 212 studies (120 regulation-focused and 92 stakeholder-focused). Figure 3 is a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram summarising record identification, screening, and inclusion for regulation- and stakeholder-focused studies. The flow illustrates how 449 records were retrieved from Scopus and Web of Science, 237 duplicates removed, 212 screened, and 212 studies included (120 regulation-focused, 92 stakeholder-focused).

- (3)

- Bibliometric Analysis: Using CiteSpace© [20], the final corpus was examined through both performance analysis (authors, journals, institutions, countries ranked by productivity and citations) and science mapping (co-citation networks, cluster detection, temporal bursts). Key metrics included modularity and silhouette (network cohesion), centrality (brokerage), and burst strength (topic surges) [21,22]. Clusters with high silhouette values were reviewed first, focusing on both central and highly cited works to capture thematic cores and bridging contributions. This process ensured a transparent, replicable mapping of how EFV regulation and stakeholder perspectives have evolved over the past 15 years.

2.2. Empirical Validation: Living-Lab Workshops

3. Literature Review

3.1. Regulation-Focused Literature

3.2. Stakeholder-Focused Literature

3.3. Cross-Cutting Gaps

4. Stakeholders’ Priorities

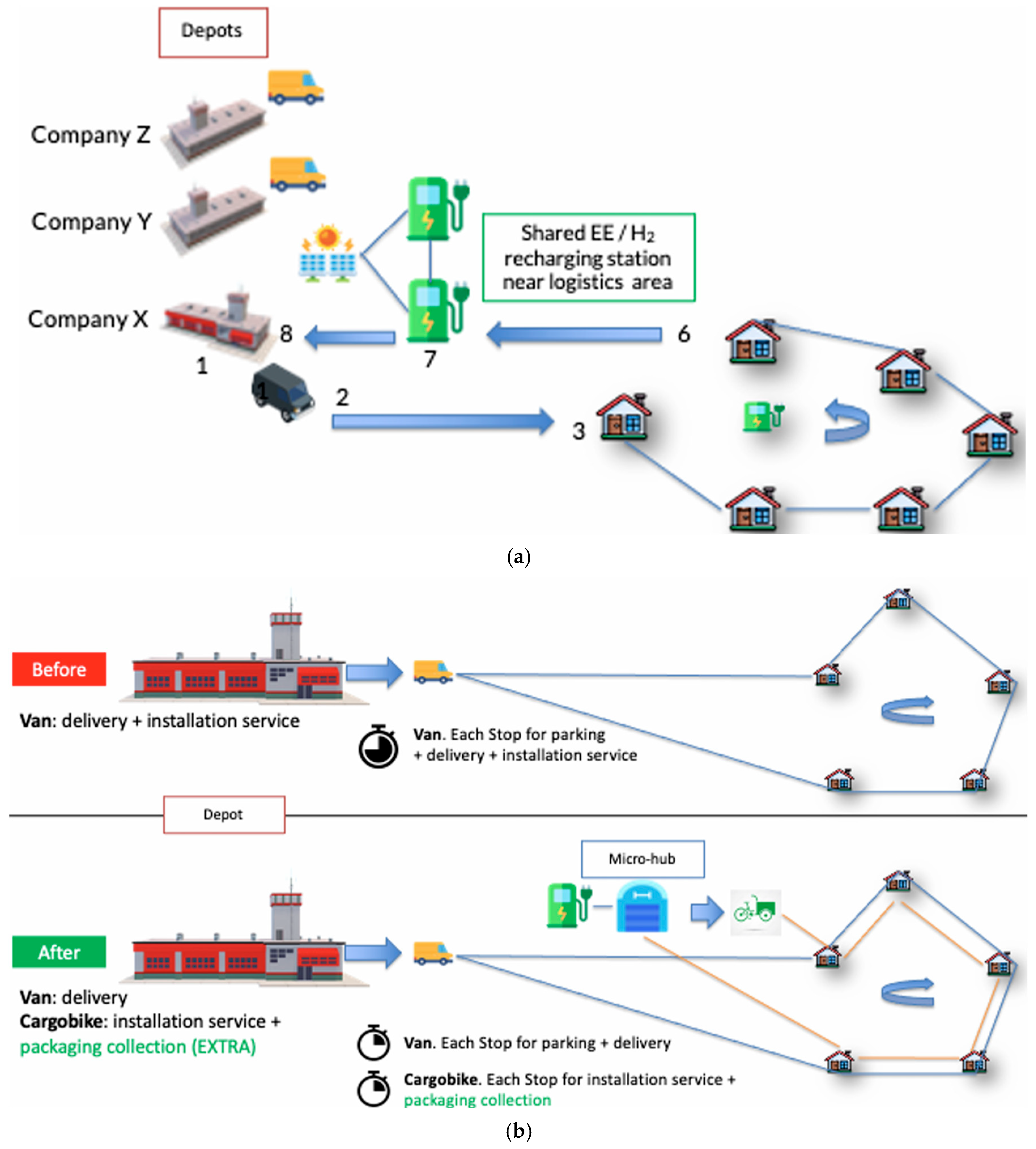

4.1. Shared Charging/Refuelling Hub (S1)

4.2. Cargo-Bike Decoupling and Reverse Logistics (S2)

4.3. Governance and Cross-Cutting Issues

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Shared Charging and Refuelling Hub (S1)

5.2. Discussion of Cargo-Bike Decoupling and Reverse Logistics (S2)

5.3. Discussion of Governance and Cross-Cutting Insights

5.4. Replicability and Transferability

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSO | Distribution System Operators |

| EFV | Eco-Friendly Vehicle |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| TCO | Total Cost of Ownership |

| LEZ | Low Emission Zone |

| ZEZ | Zero Emission Zone |

| PPP | Public–Private Partnership |

| DCM | Discrete Choice Model |

| ABM | Agent-Based Model |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PULSe | Pre-feasibility analysis for Urban Logistics Solutions based on Eco-friendly vehicles |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| EU | European Union |

| ITS | Intelligent Transport Systems |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| SP | Stated Peference |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- ALICE. Urban Freight Research & Innovation Roadmap. 2022. Available online: https://www.etp-logistics.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Urban-Freight-Roadmap.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- EEA. Transport and Mobility. 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/transport-and-mobility (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-511-80527-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E. Urban freight transport and policy changes: Improving decision makers’ awareness via an agent-specific approach. Transp. Policy 2014, 36, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrler, V.C.; Schöder, D.; Seidel, S. Challenges and perspectives for the use of electric vehicles for last mile logistics of grocery e-commerce—Findings from case studies in Germany. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 87, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliano, A.C.; Carlin, A.; Mangano, G.; Rafele, C. Analyzing the diffusion of eco-friendly vans for urban freight distribution. IJLM 2017, 28, 1218–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñuzuri, J.; Larrañeta, J.; Onieva, L.; Cortés, P. Solutions applicable by local administrations for urban logistics improvement. Cities 2005, 22, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, F.; Cavallaro, F.; Nocera, S. The integration of passenger and freight transport for first-last mile operations. Transp. Policy 2021, 100, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatnassi, E.; Chaouachi, J.; Klibi, W. Planning and operating a shared goods and passengers on-demand rapid transit system for sustainable city-logistics. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2015, 81, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.S.; Osipov, S.; Turner, J.W.G. Impact of Modern Vehicular Technologies and Emission Regulations on Improving Global Air Quality. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V.; Lozzi, G. Innovative Business Models, Governance and Public-Private Partnerships; Deliverable 1.3, LEAD Project. 2021. Available online: https://www.leadproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/LEAD-D1.3.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Kim, H.J.; Jo, S.; Kwon, S.; Lee, J.-T.; Park, S. NOX emission analysis according to after-treatment devices (SCR, LNT + SCR, SDPF), and control strategies in Euro-6 light-duty diesel vehicles. Fuel 2022, 310, 122297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, E.; Miller, J.; Bernard, Y.; Lee, K.; Rodríguez, F. The role of NOx emission reductions in Euro 7/VII vehicle emission standards to reduce adverse health impacts in the EU27 through 2050. Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Akiva, M.; Bierlaire, M. Discrete choice methods and their applications to short term travel decisions. In Handbook of Transportation Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.; Allen, J.; Nemoto, T.; Patier, D.; Visser, J. Reducing Social and Environmental Impacts of Urban Freight Transport: A Review of Some Major Cities. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 39, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E.; Pira, M.L.; Inturri, G.; Ignaccolo, M.; Pluchino, A. E-groceries and urban freight: Investigating purchasing habits, peer influence and behaviour change via a discrete choice/agent-based modelling approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 46, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, X.; Qiu, R.; Hou, S. Electric vehicle industry sustainable development with a stakeholder engagement system. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ma, J.; Fan, A.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y. Effectiveness of policies for electric commercial vehicle adoption and emission reduction in the logistics industry. Energy Policy 2024, 188, 114116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. Science Mapping: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2017, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, J. Bursty and Hierarchical Structure in Streams. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2003, 7, 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignery, K.; Laurier, W. A methodology and theoretical taxonomy for centrality measures: What are the best centrality indicators for student networks? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quak, H.; Nesterova, N.; Van Rooijen, T.; Dong, Y. Zero Emission City Logistics: Current Practices in Freight Electromobility and Feasibility in the Near Future. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Rodríguez, F. Electrifying Last-Mile Delivery: A Total Cost of Ownership Comparison of Battery-Electric and Diesel Trucks in Europe; International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- González-Varona, J.M.; Villafáñez, F.; Acebes, F.; Redondo, A.; Poza, D. Reusing Newspaper Kiosks for Last-Mile Delivery in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzolo, A.; Persia, L.; Polimeni, A. Agent-Based Simulation of urban goods distribution: A literature review. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 30, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh Ghoushchi, S.; Shaffiee Haghshenas, S.; Vahabzadeh, S.; Guido, G.; Geem, Z.W. An integrated MCDM approach for enhancing efficiency in connected autonomous vehicles through augmented intelligence and IoT integration. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilas, V.; Demir, E.; Van Woensel, T. The pickup and delivery problem with time windows and scheduled lines. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2016, 54, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.; Teixeira, L.; Marques, J.L. Last-mile-as-a-service (LMaaS): An innovative concept for the disruption of the supply chain. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, S.; Baptista, P. Evaluating the impacts of using cargo cycles on urban logistics: Integrating traffic, environmental and operational boundaries. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, B.S.; Sahu, P.K. Assessing regional transferability and updating of freight generation models to reduce sample size requirements in national freight data collection program. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 175, 103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Comi, A. Investigating the Effects of City Logistics Measures on the Economy of the City. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureeyatanapas, P.; Poophiukhok, P.; Pathumnakul, S. Green initiatives for logistics service providers: An investigation of antecedent factors and the contributions to corporate goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, O.; Tan, T.; Udenio, M. Transitioning to sustainable freight transportation by integrating fleet replacement and charging infrastructure decisions. Omega 2022, 109, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanar, T. Understanding the choice for sustainable modes of transport in commuting trips with a comparative case study. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 11, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Phrase (Set 3.1) | Documents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WoS | Scopus | Excluded | Total | Duplicates | Reviewed | |

| “regulation” OR “regulatory” OR “ordinance” OR “decree” OR “ban” OR “incentive*” OR “subsid*” OR “tax*” OR “zero emissions” OR “LEZ” OR “ZEZ” OR “enforcement” OR “sanction*” OR “complian*” OR “measures” OR “polic*” | 163 | 146 | 26 | 283 | 163 | 120 |

| Search Phrase (Set 3.2) | Documents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WoS | Scopus | Excluded | Total | Duplicates | Reviewed | |

| “stakeholder*” OR “player*” OR “actor” OR “agent” OR “industry” OR “suppliers” OR “shippers” OR “carrier” OR “receiver” OR “policymaker” OR “end-consumer” OR “end consumer” OR “acceptability” | 74 | 108 | 16 | 166 | 74 | 92 |

| Stakeholder | Organisation Type | Participants (n) | Focus Solution | Key Consensus | Key Dissent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DACHSER-FERCAM | Logistics Operator | 2 (Senior Ops) | S1 | Need for night charging | Cost recovery model |

| Doctor Bike | Cargo-bike operator | 2 (Managers) | S2 | Rider training essential | Tariff structure |

| MOTUS-E | e-mobility alliance | 2 | S1 & S2 | Neutral governance critical | Subsidy design |

| Switch | Tech/IoT provider | 1 | S2 | Dispatcher platform feasibility | Integration with the city API |

| A2A | Utility/energy provider | 2 | S1 | Grid coordination vital | Land-use permitting |

| Indicator | Solution 1—Shared Charging/Refuelling Hub (S1) | Solution 2—Cargo-Bike Decoupling & Reverse Logistics (S2) | Source/Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical daily operating range | 120–200 km per vehicle | 25–30 delivery tasks per rider per day | Operator feedback (DACHSER-FERCAM; Doctor Bike) |

| Charging/handover duration | Overnight (17:00–06:00) + fast charge 30–45 min | Handover between van and rider within 15–20 min | Living Lab data + literature |

| Peak power demand | ≈400 kW (10 fast chargers × 40 kW each) | n/a—battery swap and slow charge at micro-hubs (1–2 kW per unit) | A2A technical inputs |

| Utilisation rate | 70–85% (expected, shared access) | 80–90% fleet availability (target) | Stakeholder estimates |

| Indicative CAPEX/OPEX | CAPEX ≈ €0.8–1.2 million OPEX ≈ €60–80 k/year | CAPEX ≈ €3–5 k per bike OPEX ≈ €1 k/year (battery + maintenance) | Literature + project data |

| Emission reduction potential | ≈70% vs. diesel fleet (based on energy mix) | ≈65% vs. diesel van for inner-city deliveries | Estimated from the literature |

| Key bottleneck/risk | Grid capacity and land-use permitting | Rider training and dispatch reliability | Workshop discussion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erriu, R.; Balla, B.S.; Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V.; Comi, A.; Napoli, G.; Polimeni, A. Regulatory Enablers and Stakeholders’ Acceptance in Defining Eco-Friendly Vehicle Logistics Solutions for Rome. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040188

Erriu R, Balla BS, Marcucci E, Gatta V, Comi A, Napoli G, Polimeni A. Regulatory Enablers and Stakeholders’ Acceptance in Defining Eco-Friendly Vehicle Logistics Solutions for Rome. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040188

Chicago/Turabian StyleErriu, Riccardo, Bhavani Shankar Balla, Edoardo Marcucci, Valerio Gatta, Antonio Comi, Giuseppe Napoli, and Antonio Polimeni. 2025. "Regulatory Enablers and Stakeholders’ Acceptance in Defining Eco-Friendly Vehicle Logistics Solutions for Rome" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040188

APA StyleErriu, R., Balla, B. S., Marcucci, E., Gatta, V., Comi, A., Napoli, G., & Polimeni, A. (2025). Regulatory Enablers and Stakeholders’ Acceptance in Defining Eco-Friendly Vehicle Logistics Solutions for Rome. Future Transportation, 5(4), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040188