A Heuristic Approach for Truck and Drone Delivery System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work and Technologies

2.1. Literature Review on UAVs in Delivery Systems

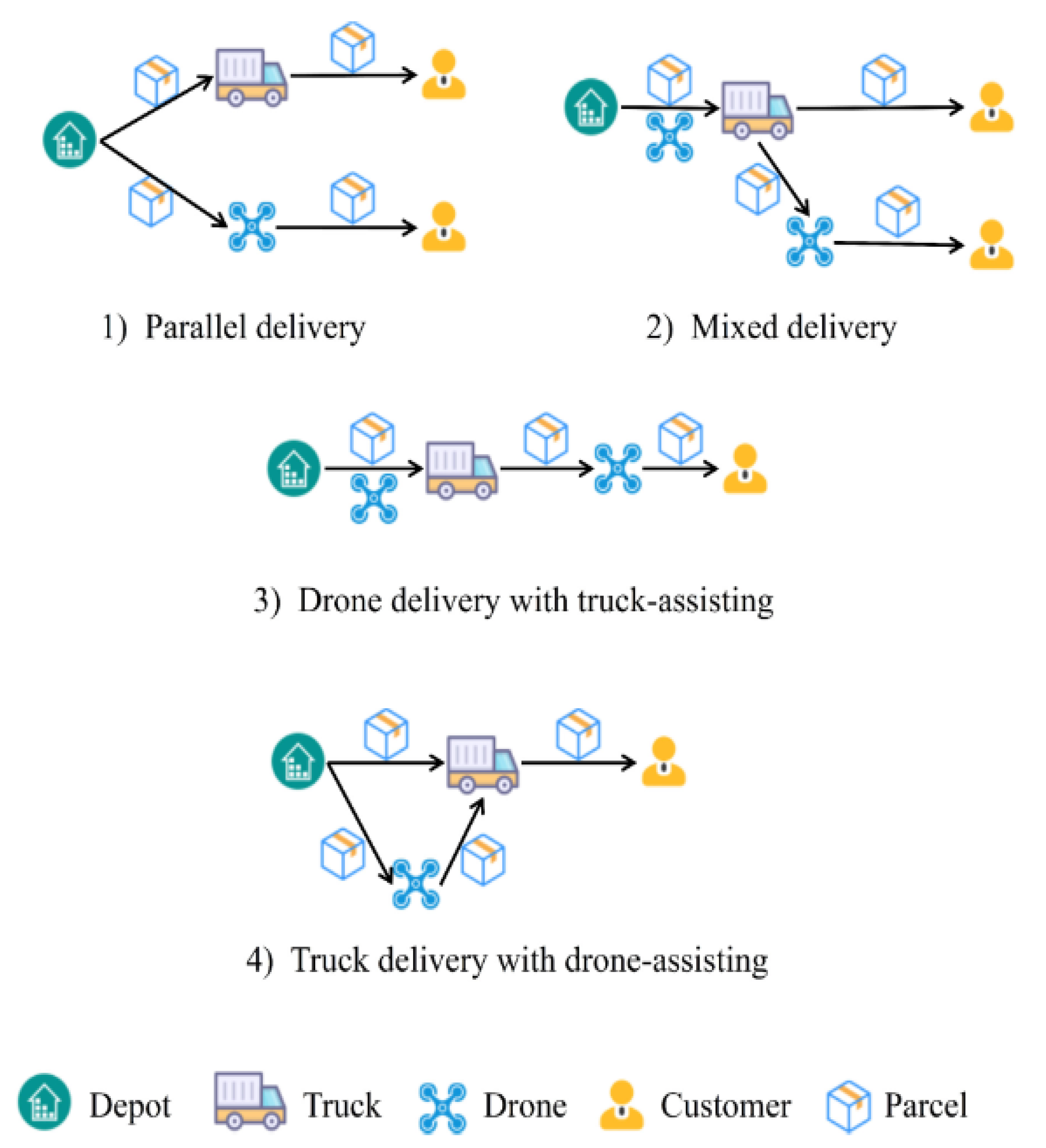

2.2. Drone-Assisted Last-Mile Delivery Models

2.3. The Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

2.4. FSTSP (Flying Sidekick Traveling Salesman Problem)

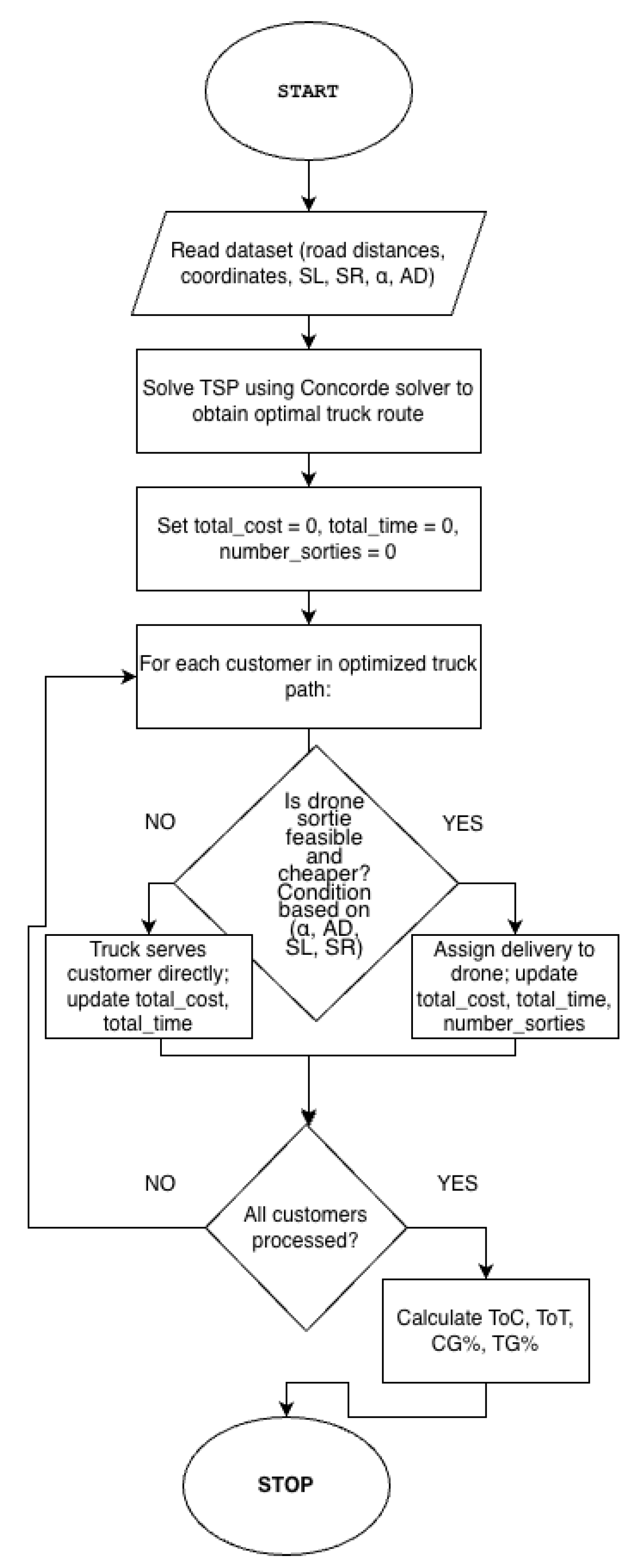

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Method Description

| number_sorties = 0 |

| SORT savings_candidates DESC on saving_value |

| FOR EACH (saving_value) IN savings_candidates: |

| IF saving_value > 0 AND customer_to_serve_by_drone NOT IN drone_served_customers: |

| drone_missions.ADD( |

| launch_node = prev_node_truck, |

| delivery_node = customer_to_serve_by_drone, |

| recovery_node = next_node_truck, |

| cost = actual_drone_cost ) |

| drone_served_customers.ADD(customer_to_serve_by_drone) |

| UPDATE costs, number_sorties = number_sorties + 1 |

| REMOVE customer_to_serve_by_drone FROM optimized_truck_path |

| END IF |

| END FOR |

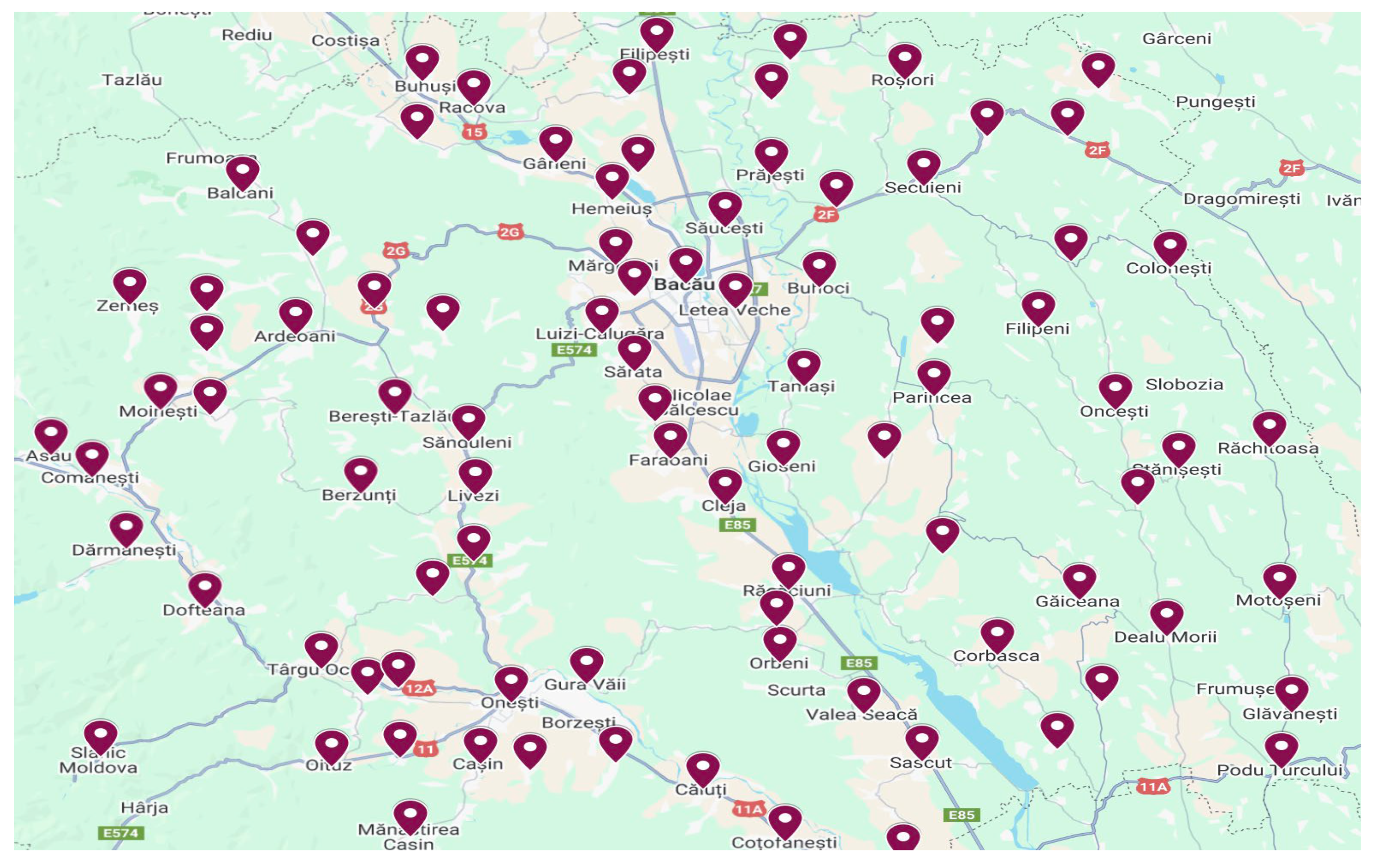

3.2. The Data Used

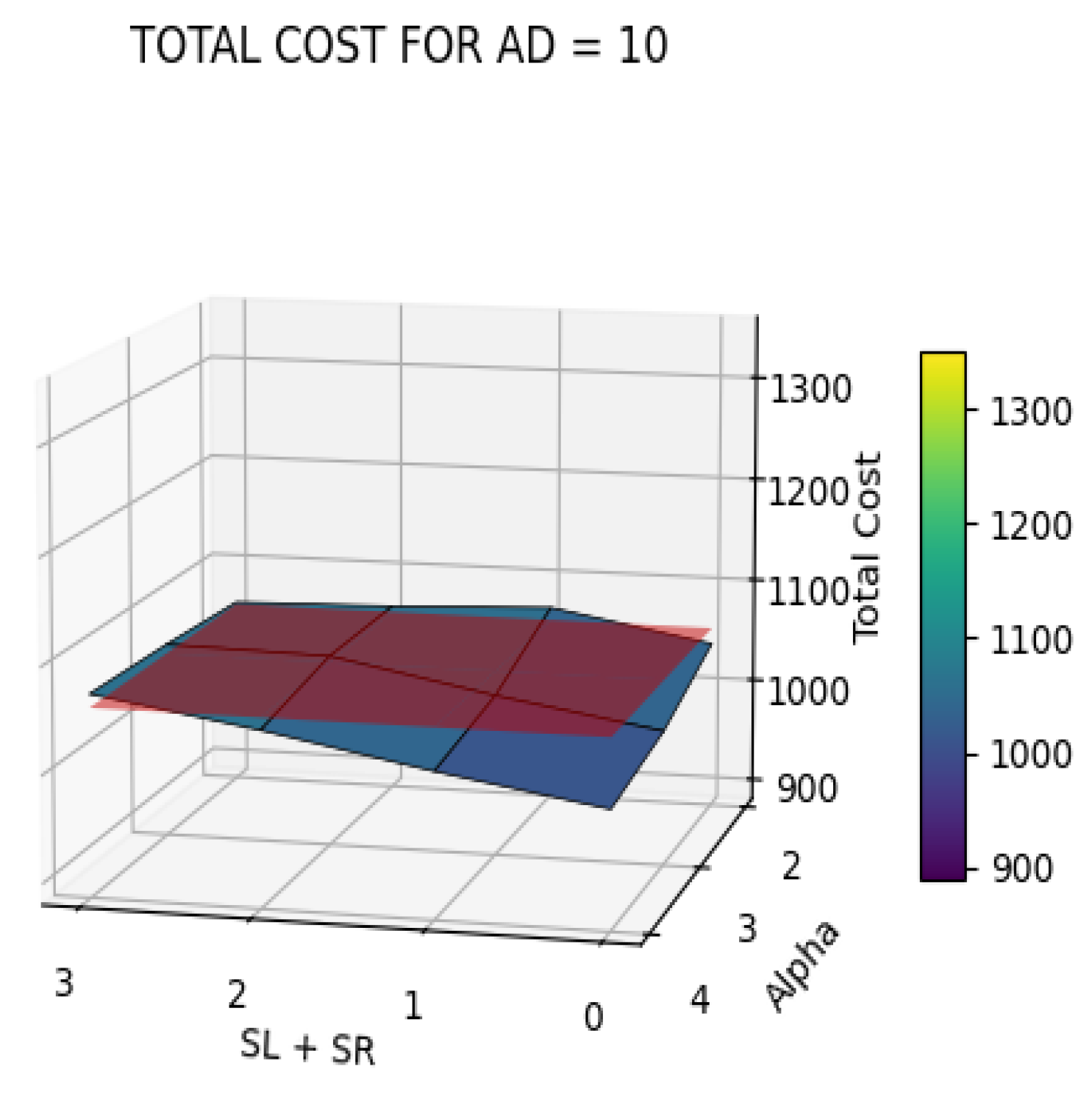

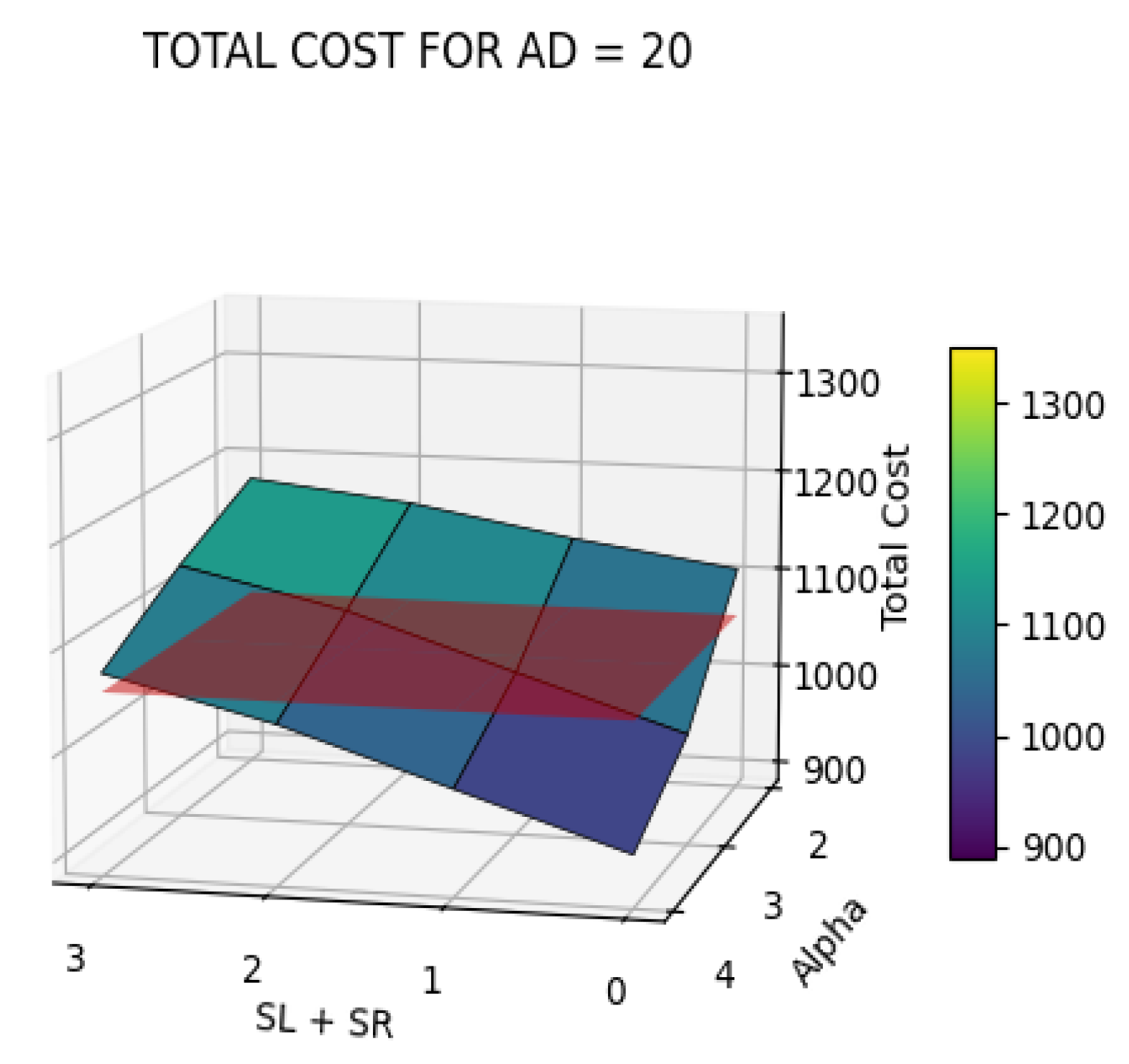

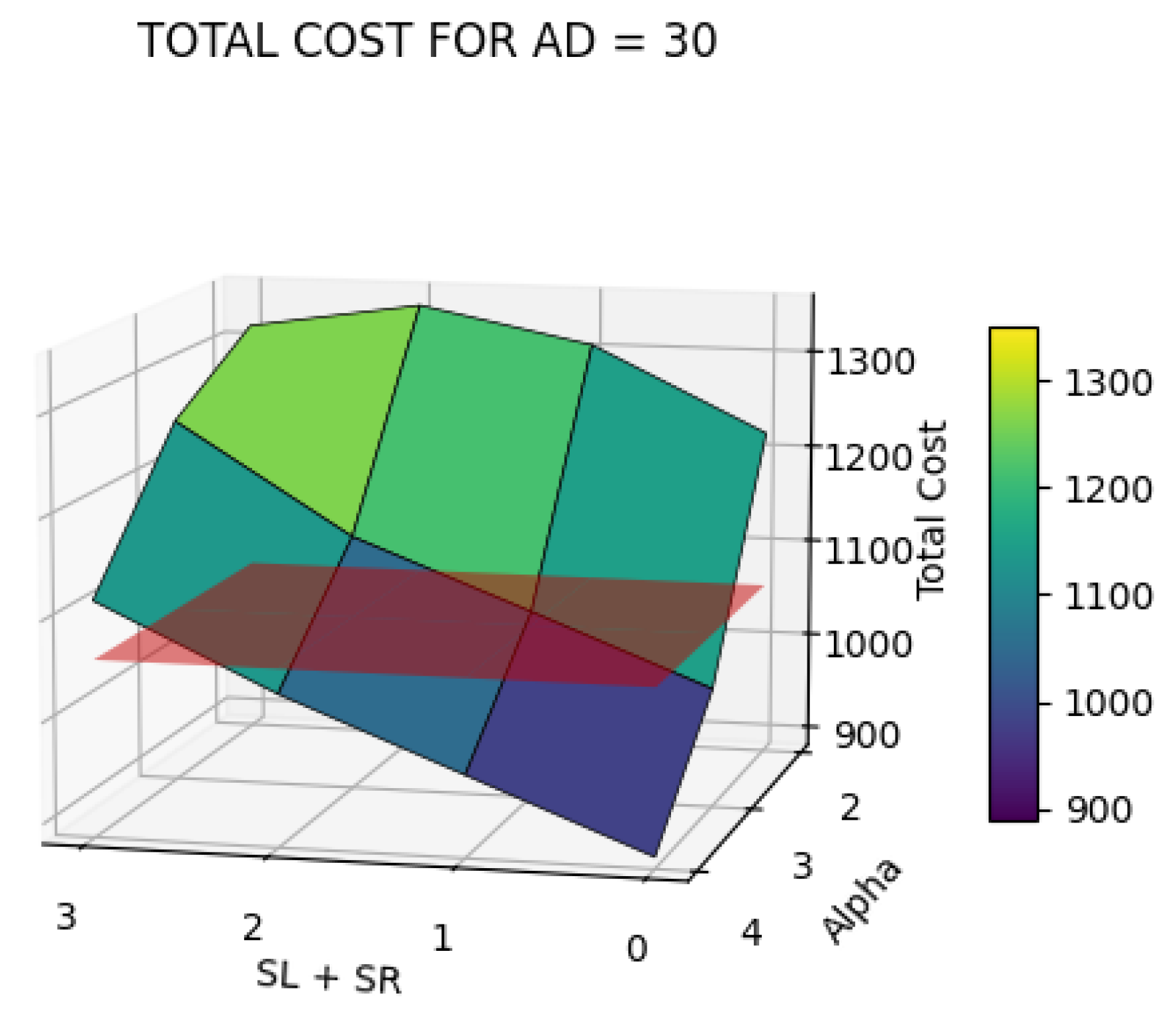

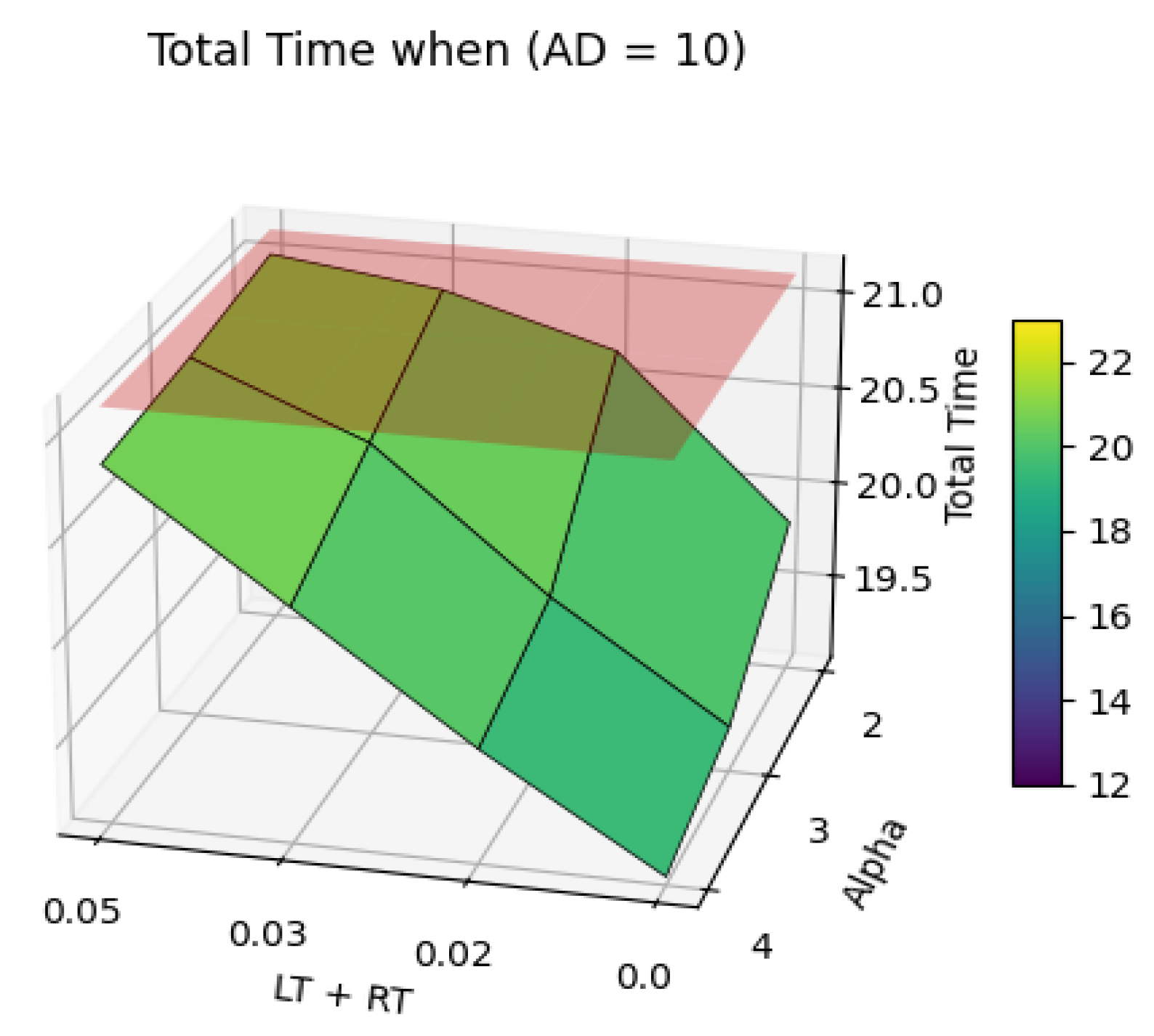

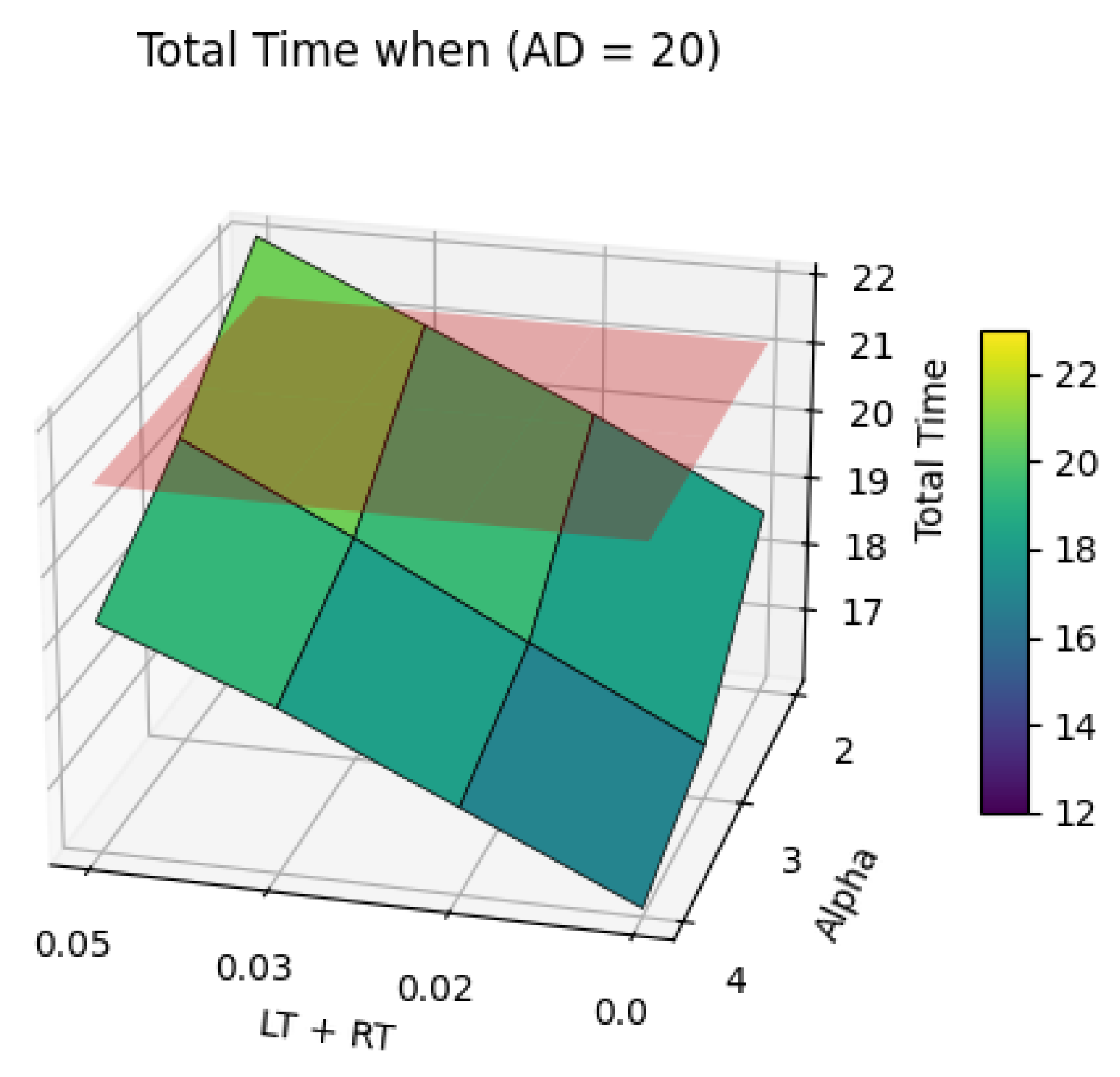

4. Computational Experiment

5. Discussion

- If no penalties are applied (SL = SR = 0), NS depends strictly on AD: NS = 25 if AD = 10; NS = 52 if AD = 20; NS = 70 if AD = 30. In this case, the drone speed has no impact on NS.

- If penalties are small (SL = SR = 0.5), NS is influenced by the drone speed only if the drone is slow: NS = 22/44/59 if α = 2 and AD = 10/20/30; NS = 25/52/70 if α > 2 and AD = 10/20/30;

- If each penalty is larger than 0.5, then the value of NS is influenced by all the parameters. If the optimization problem considers also minimizing NS, then the study must be oriented on high-speed drones, which really impact this variable.

Experimental Assumptions and Their Rationale

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahani, H.; Khosravi, Y.; Kargar, B.; Ong, K.L.; Arisian, S. Exploring the role of drones and UAVs in logistics and supply chain management: A novel text-based literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 63, 1873–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstknecht, M.; Boysen, N.; Briskorn, D. The traveling salesman problem with drone resupply. OR Spectr. 2022, 44, 1045–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, R.; Ruthmair, M. Exact methods for the traveling salesman problem with drone. Transp. Sci. 2019, 53, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Tilk, C.; Irnich, S. Exact Solution of the Vehicle Routing Problem with Drones; Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz: Mainz, Germany, 2023; Working Paper No. 2311; Available online: https://download.uni-mainz.de/RePEc/pdf/Discussion_Paper_2311.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Imran, N.; Won, M. VRPD DT: Vehicle Routing Problem with Drones under Dynamically Changing Traffic Conditions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.09065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEOS Server. Concorde TSP Solver. Available online: https://neos-server.org/neos/solvers/co:concorde/TSP.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- DHL Group. DHL Launches Its First Regular Fully Automated and Intelligent Urban Drone Delivery Service. Available online: https://group.dhl.com/en/media-relations/press-releases/2019/dhl-launches-its-first-regular-fully-automated-and-intelligent-urban-drone-delivery-service.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- FedEx. Wing Drones Transport FedEx Deliveries Directly to Homes. Available online: https://www.fedex.com/ro-ro/about/sustainability/our-approach/wing-drones-transport-fedex-deliveries-directly-to-homes.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Guebsi, R.; Mami, S.; Chokmani, K. Drones in precision agriculture: A comprehensive review of applications, technologies, and challenges. Drones 2024, 8, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Kumar, N.; Soni, S.; Hafeez, A.; Singh, S.; Khan, M.; Husain, M.; Chauhan, A. Implementation of drone technology for farm monitoring & pesticide spraying: A review. Inf. Process. Agric. 2022, 10, 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kindervater, K. The emergence of lethal surveillance: Watching and killing in the history of drone technology. Secur. Dialogue 2016, 47, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwon, O.; Yang, T.; Kim, J.; Cho, N.; Choi, M.; Lee, M. A study on the advancement of intelligent military drones: Focusing on reconnaissance operations. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55964–55975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarmand, M.; Shahriari, H. Geological mapping using drone-based photogrammetry: An application for exploration of vein-type Cu mineralization. Minerals 2021, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Anil, N.; Snehith, S.; Bansod, S.; Singh, S.; Srikanth, K.; Kumar, Y. Revolutionizing spatial data collection: The advancements and applications of 3D mapping with drone technology (photogrammetry). In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing in Emerging Markets (CCEM), Bengaluru, India, 2–4 November 2023; pp. 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, S.; Maldague, X.; Genest, M.; Nooralishahi, P.; Ibarra-Castanedo, C.; Deane, S.; Avdelidis, N.; López, F. Drone-based non-destructive inspection of industrial sites: A review and case studies. Drones 2021, 5, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, H.; Antón, N.; Villarino, A.; Cubillos, X.; Domínguez, M. UAV applications for monitoring and management of civil infrastructures. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Huang, H.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Y. Unmanned aerial vehicles for search and rescue: A survey. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Kieseberg, P.; Tschiatschek, S.; Eresheim, S.; Stampfer, K.; Buchelt, A.; Nothdurft, A.; Gollob, C.; Adrowitzer, A. Exploring artificial intelligence for applications of drones in forest ecology and management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 549, 121530. [Google Scholar]

- Bezyk, Y.; Arsen, A.; Pawnuk, M.; Jońca, J.; Sówka, I. Drone-assisted monitoring of atmospheric pollution—A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11516. [Google Scholar]

- Velfl, L.; Bureš, V.; Důbravová, H. Review of the application of drones for smart cities. IET Smart Cities 2024, 6, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, W.; Hunaiti, Z.; Al-Dosari, K. Systematic review on civilian drones in safety and security applications. Drones 2023, 7, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.; Chu, A. The flying sidekick traveling salesman problem: Optimization of drone-assisted parcel delivery. Transp. Res. Part C 2015, 54, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adle, A.; Haouari, M.; Ghoniem, A. Parcel delivery by vehicle and drone. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2019, 72, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.H.; Sah, B.; Lee, J. Optimization for drone and truck cooperation logistics systems: A review of the state of the art and future directions. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 123, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponza, M. Optimization Models for Drone Deliveries. Master’s Thesis, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, N.; Attenni, G.; Arrigoni, V.; Maselli, G. Drone-based delivery systems: A survey on route planning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 123476–123504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qiao, W. Solving large-scale function optimization problem by using a new metaheuristic algorithm based on quantum dolphin swarm algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 138972–138989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Kernighan, B. An effective heuristic algorithm for the traveling–salesman problem. Oper. Res. 1973, 21, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F.; Laguna, M. Tabu Search; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Stützle, T. Ant Colony Optimization; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Dou, L.; Xin, B.; Chen, C.; Deng, F.; Chen, J. A review on the truck and drone cooperative delivery problem. Unmanned Syst. 2023, 12, 823–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkki, A.; Tikanmäki, A.; Röning, J. Automatic Jig-Assisted Battery Exchange for Lightweight Drones. Machines 2024, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, V. Method for Automatic Loading and Unloading of Shipments in an Unmanned Aircraft and Mechanism for Automatic Loading and Unloading of Shipments in an Unmanned Aircraft. EP Patent EP3957562A1, 23 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

| SL | SR | Alpha | AD | NS | TrC (km) | DrC (km) | ToC (km) | CG % | LT + RT (h) | ToT (h) | TG % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 10 | 25 | 942.40 | 99.01 | 1041.41 | 1.47% | 0.00 | 19.84 | 6.16% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 10 | 22 | 960.50 | 108.73 | 1069.23 | −1.16% | 0.02 | 20.66 | 2.25% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 2 | 10 | 14 | 980.50 | 82.18 | 1062.68 | −0.54% | 0.03 | 20.90 | 1.14% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 10 | 9 | 996.70 | 62.20 | 1058.90 | −0.18% | 0.05 | 21.01 | 0.63% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 10 | 25 | 942.40 | 66.00 | 1008.40 | 4.60% | 0.00 | 19.29 | 8.76% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 | 10 | 25 | 942.40 | 91.00 | 1033.40 | 2.23% | 0.02 | 19.87 | 6.00% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 10 | 24 | 951.70 | 111.02 | 1062.72 | −0.54% | 0.03 | 20.57 | 2.68% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 3 | 10 | 15 | 980.20 | 85.52 | 1065.72 | −0.82% | 0.05 | 20.92 | 1.02% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 10 | 25 | 942.40 | 49.50 | 991.90 | 6.16% | 0.00 | 19.10 | 9.67% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 10 | 25 | 942.40 | 74.50 | 1016.90 | 3.79% | 0.02 | 19.64 | 7.11% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 4 | 10 | 25 | 945.70 | 99.67 | 1045.37 | 1.10% | 0.03 | 20.25 | 4.23% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 4 | 10 | 22 | 960.50 | 109.36 | 1069.86 | −1.22% | 0.05 | 20.86 | 1.34% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 20 | 52 | 758.90 | 345.32 | 1104.22 | −4.47% | 0.00 | 18.63 | 11.87% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 20 | 44 | 782.70 | 345.16 | 1127.86 | −6.70% | 0.02 | 19.84 | 6.15% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 2 | 20 | 38 | 809.40 | 347.71 | 1157.11 | −9.47% | 0.03 | 20.93 | 0.99% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 20 | 30 | 876.20 | 299.56 | 1175.76 | −11.24% | 0.05 | 22.02 | −4.16% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 20 | 52 | 758.90 | 230.21 | 989.11 | 6.42% | 0.00 | 16.71 | 20.94% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 | 20 | 52 | 758.90 | 282.21 | 1041.11 | 1.50% | 0.02 | 17.93 | 15.20% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 20 | 51 | 764.90 | 329.00 | 1093.90 | −3.49% | 0.03 | 19.19 | 9.22% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 3 | 20 | 44 | 797.70 | 333.34 | 1131.04 | −7.00% | 0.05 | 20.38 | 3.61% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 20 | 52 | 758.90 | 172.66 | 931.56 | 11.87% | 0.00 | 16.04 | 24.12% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 20 | 52 | 758.90 | 224.66 | 983.56 | 6.95% | 0.02 | 17.17 | 18.79% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 4 | 20 | 52 | 758.90 | 276.66 | 1035.56 | 2.03% | 0.03 | 18.29 | 13.46% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 4 | 20 | 50 | 756.00 | 319.13 | 1075.13 | −1.72% | 0.05 | 19.22 | 9.10% |

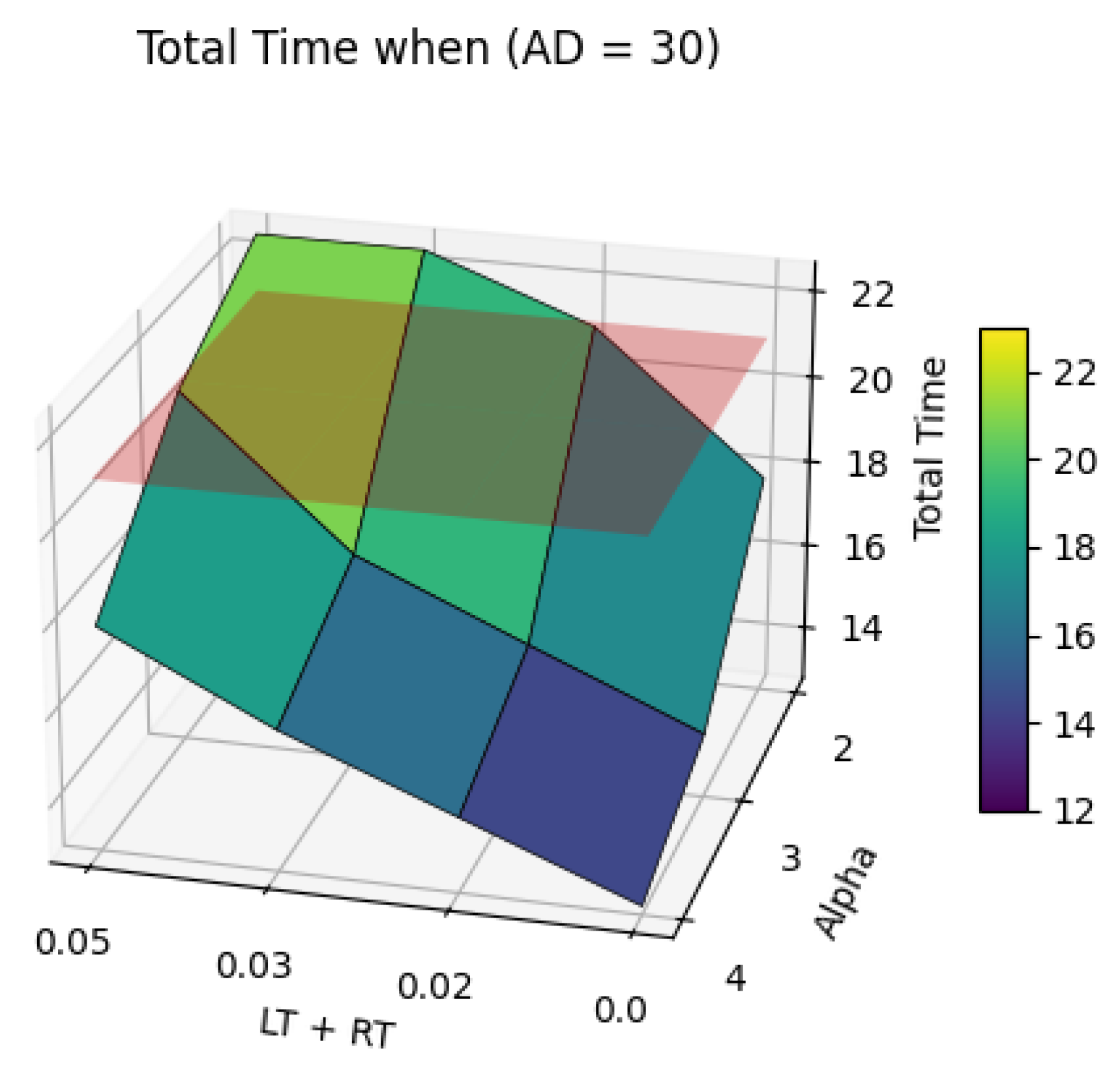

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 30 | 70 | 566.60 | 651.25 | 1217.85 | −15.22% | 0.00 | 17.84 | 15.59% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 30 | 59 | 699.70 | 604.70 | 1304.40 | −23.41% | 0.02 | 21.02 | 0.55% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 2 | 30 | 53 | 727.70 | 612.74 | 1340.44 | −26.82% | 0.03 | 22.45 | −6.19% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 30 | 49 | 688.90 | 624.15 | 1313.05 | −24.22% | 0.05 | 22.47 | −6.29% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 30 | 70 | 566.60 | 434.17 | 1000.77 | 5.32% | 0.00 | 14.23 | 32.70% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 | 30 | 70 | 566.60 | 504.17 | 1070.77 | −1.30% | 0.02 | 15.86 | 24.98% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 30 | 69 | 572.70 | 566.84 | 1139.54 | −7.81% | 0.03 | 17.53 | 17.06% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 3 | 30 | 56 | 732.00 | 518.90 | 1250.90 | −18.34% | 0.05 | 20.90 | 1.14% |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 30 | 70 | 566.60 | 325.62 | 892.22 | 15.59% | 0.00 | 12.96 | 38.69% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 30 | 70 | 566.60 | 395.62 | 962.22 | 8.97% | 0.02 | 14.48 | 31.52% |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 4 | 30 | 70 | 566.60 | 465.62 | 1032.22 | 2.34% | 0.03 | 15.99 | 24.35% |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 4 | 30 | 68 | 593.20 | 522.27 | 1115.47 | −5.53% | 0.05 | 17.88 | 15.44% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conea, S.I.; Crisan, G.C. A Heuristic Approach for Truck and Drone Delivery System. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040181

Conea SI, Crisan GC. A Heuristic Approach for Truck and Drone Delivery System. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040181

Chicago/Turabian StyleConea, Sorin Ionut, and Gloria Cerasela Crisan. 2025. "A Heuristic Approach for Truck and Drone Delivery System" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040181

APA StyleConea, S. I., & Crisan, G. C. (2025). A Heuristic Approach for Truck and Drone Delivery System. Future Transportation, 5(4), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040181