1. Introduction

In rapidly developing metro areas, public transport greatly supports sustainable growth because it helps manage mobility challenges for the city and the environment. In places like Greater Cairo, having a strong public transport system reduces harmful traffic fumes and allows all people to reach jobs, education, and essential services more easily. Even though Cairo’s public transport is crucial, there are ongoing problems with running services smoothly and making the most of their money [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Although investment has gone into improving infrastructure and increasing the fleet, many deeper problems remain unaddressed. Services are used differently across the system, the fare rates are not responsive, and transit performance is not often measured internationally. The outcome is a system for moving people that falls short of meeting needs and runs below its capacity for efficiency. As a result, approaches that blend today’s economic theories, statistical modeling, and comparisons with different policies are required [

5,

6].

The study examines the extent of efficiency that exists in each of Cairo’s three main public transport modes—buses, special services, and minibuses—with respect to revenue generation and operational reliability. It applies ARIMA models [

7,

8] and tools for forecasting revenue trends, math optimization [

9], and comparing Cairo to peer cities facing the same city challenges. Using a combination of analysis and comparison, locally sourced results support insights that can be relevant everywhere. This paper presents a method for solving the modeling problem and an analysis of peer cities facing the same challenges as Cairo. Through a blend of analysis and comparison, locally sourced results back up insights that could matter to anyone.

Together, the forecasting–optimization–policy–analysis approach utilized in this paper is a contribution to the analysis of existing research gaps and an agenda for filling those gaps. Having characterized the data, the analysis proposes remedies that arise from facts and that succeed based on sound theory. Through this detailed methodology, the research aims to provide advancements and guidance to the field of urban transport economics as well as to offer practical advice for planners and policy-makers in charge of reducing car dependence by moving towards greater sustainability.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of the literature on transport efficiency, economic modeling, and dynamic pricing. In

Section 3, we briefly outline the theoretical framework that drives the approach of this work.

Section 4 describes the methodological design in terms of data sources, analysis models, and benchmarking procedures.

Section 5 presents the empirical findings and

Section 6 concludes with policy implications. The paper is concluded with thoughts on extended applications and avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transport Efficiency Metrics

The performance of the public transport systems is often evaluated using indicators like RPK (revenue per kilometer), CPK (cost per kilometer), and LF (load factor). They make it possible to measure both finances and how resources are used. RPK shows the efficiency of turning travel into income, and CPK measures the money spent per distance flown. Service utilization efficiency is measured by the LF, which represents the ratio of seats taken to total capacity.

According to Rogerson and Sallnäs [

10], keeping high load factors in logistics requires coordination within the company, and in public transport, vehicle schedules and deployment impact how many passengers can be carried. Likewise, Santén [

11] considered how load factors can be lifted in road transport systems by recommending that leaders plan services, manage demand, and control capacity together.

2.2. Multicriteria Decision Methods in Transport Evaluation

Multicriteria analysis (MCA) has become a reliable system for helping in transport studies, mainly when considering performance under varying and sometimes contradictory criteria. Kumar and colleagues [

12] developed a framework supported by four MCDM techniques—Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), VIšekriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje (VIKOR), and Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI)—to review Indian public transport systems using 23 criteria. Their model made it possible to compare and rank operators based on their functions.

Further MCA approaches were introduced by Jiménez-Delgado et al. [

13], with Fuzzy AHP being used to evaluate performance when uncertainties are involved. With the aid of these tools, transport agencies no longer need to zoom in one by one on various metrics to inform their best decisions.

2.3. Dynamic Modeling and Forecasting in Public Transport

Dynamic pricing is the real key issue for transport economists, because it could be used to smooth ticket fares with demand and also support environmental goals. Branda et al. [

14] proposed using event logs of a ticketing system to forecast purchases and update fares quickly in a data analytics platform (DA4PT), which led to increased revenue and ticket sales. Reinforcement learning algorithms are applied to explore the principle of whether or not employing real-time routing and pricing for buses is conducive to both maintaining passenger happiness and being sustainable. These approaches would see operators being paid and users receiving better service faster [

15].

Reliability methods are also fundamental in current transportation plans. A multi-modal agent-based approach by Kilani et al. [

16] attempted to understand how Northern France policies, e.g., toll roads and free public transport, influence emissions and congestion. The work in this line of research demonstrates the utility of simulation in obtaining granular policy insights about time and space. Meanwhile, the use of ARIMA models for forecasting the transportation income in Cairo is beneficial. Integrating these techniques with sensitivity statistics such as Sobol indices makes the optimization process more robust to deal with complex systems, allowing the decision-maker to focus on which variables deserve special attention.

2.4. Benchmarking Practices in Urban Transit

Benchmarking helps cities compare with international peers on how well their transport systems are performing. The DEA efficiency models of Hilmola [

17] estimated that the most significant proportion, almost 50 cities, showed a tremendous difference in service productivity between transit systems. In addition, Anderson et al. [

18] emphasized the use of quality of service and consumer convenience indicators in the benchmarking studies for such networks. These frameworks are necessary for regions with local metrics that cannot be compared directly with international ones, such as Greater Cairo.

2.5. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite a wealth of metrics, models, and comparative approaches in the existing literature, some gaps persist. Firstly, not many studies can incorporate planning (forecasting) and control (optimization and benchmarking) layers together in a comprehensive decision framework. Secondly, dynamic pricing models for this context have not taken into consideration demand fluctuations by time and culture (e.g., due to prayer times or holiday seasons). Thirdly, the application of simulation-based optimization in developing countries with data scarcity and informal transit combined with formal networks is less evident.

In order to bridge these gaps, this paper puts forward a comprehensive combinatorial model that relies on local data from Greater Cairo and combines econometric projections with dynamic pricing policies and international comparisons. Combining these approaches improves the performance of internal systems and extends the global significance of insights from developing cities.

3. Theoretical Framework

Opportunities for improvement can only be found through solid theories that guide fair, efficient, and sustainable operations for public transport systems. Here, we merge dynamic pricing theory and the avoid–shift–improve paradigm to create a complete urban mobility model in Greater Cairo. The value of these structural models increases when they are brought together and applied practically.

3.1. Dynamic Pricing Theory

Public transport agencies use dynamic pricing to match ticket costs with peak hours, lower costs, and allow passengers to afford them. Due to this approach, which uses microeconomics, operators can now handle demand problems, including peak-hour traffic jams, unused vehicles, and different degrees of service access. Shifting fares for different periods allows agencies to distribute demand, ease overcrowding, and raise the system’s efficiency, although expensive works are usually not required.

Therefore, using equity-based segmentation allows users with all levels of payment ability to access the service. Fair structures for fares help students and the elderly, and raising the price of premium services only affects those who want expensive transportation. Doing this helps ensure that everyone benefits socially and financially.

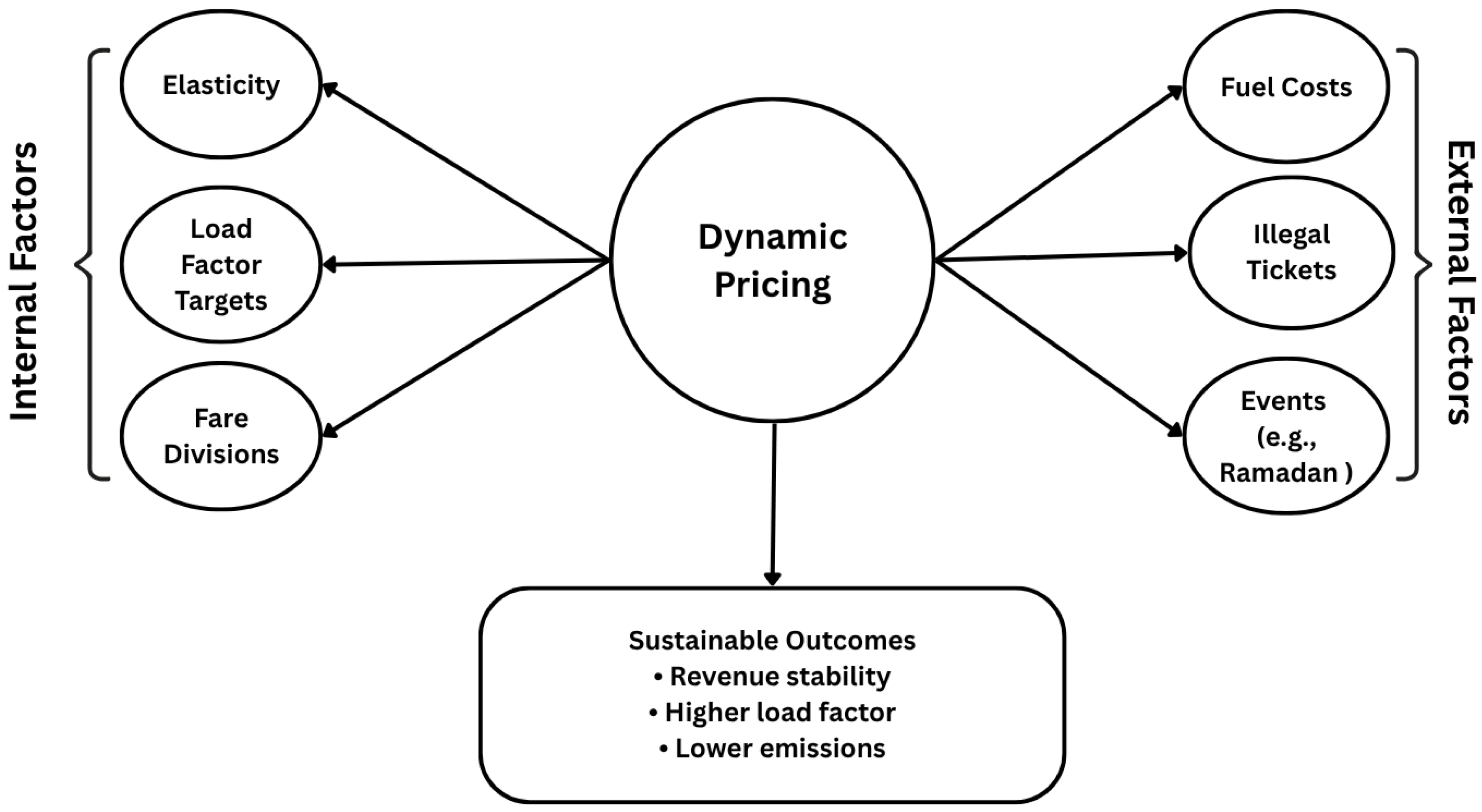

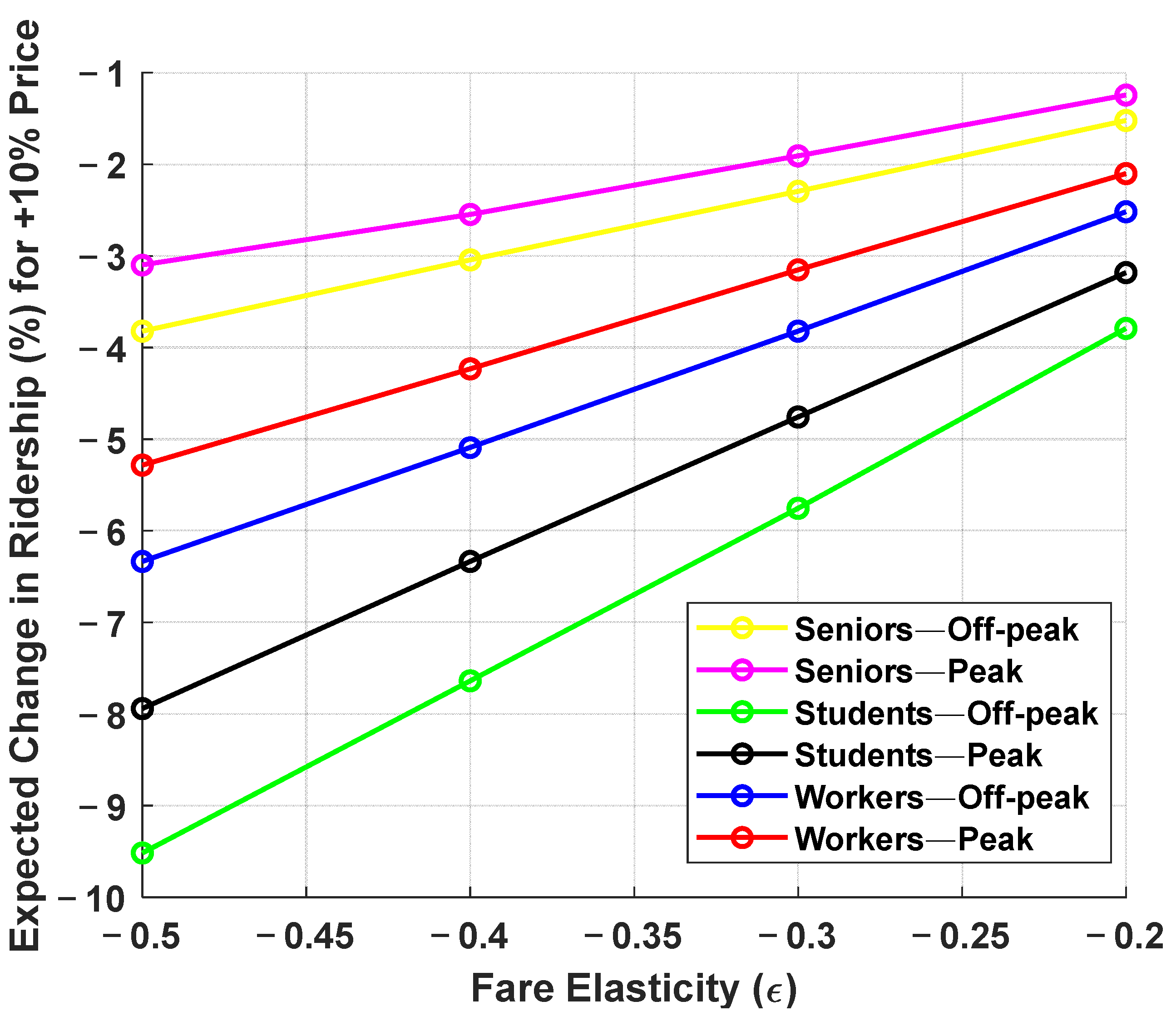

Elasticity-sensitive modeling means fares are flexible enough to change with anticipated differences in rider numbers.

Figure 1 demonstrates that user segments do not respond consistently to modest variations in ticket prices. With this model, authorities can find prices that lead to higher revenue without hurting fairness for users or breaking social goals.

3.2. Avoid–Shift–Improve Framework

Urban mobility can be decarbonized and improved using the A-S-I framework, as most sustainable transport policy work recommends. The “Avoid” dimension uses planning and online platforms to help reduce the number of trips people must take. In particular, Cairo is looking at Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) [

19] and home-based work to help reduce the number of kilometers cars drive during crowded times.

“Shift” encourages travelers to take public transportation, walk, or bike instead of driving. Early steps toward the concept can be seen in Cairo’s new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors and improved river transport. The “Improve” dimension aims to enhance the tech we already use in transport. Through the Cairo Air Improvement Project, moving diesel buses to compressed natural gas has already resulted in a 37% in particulate emissions.

Table 1 presents a matrix of current and proposed interventions aligned with the A-S-I logic, contextualized for Greater Cairo.

3.3. Synergistic Model Integration

Using dynamic pricing with A-S-I leads to positive results for the company’s finances and the environment. For example, affordable tickets during off-peak hours (“Pricing → Shift”) motivate individuals to use different modes when few people usually travel. Higher utilization of off-peak hours improves how fleets run and makes it more worthwhile to buy greener vehicles (“Shift → Improve”). In addition, when improvements in reliability and cost happen (“Improve”), it encourages fewer unnecessary journeys (“Avoid”).

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the effect of fare elasticity on ridership change is quite different among user categories and time periods. The elasticity of demand in response to a 10% increase in fare is shown for all off-peak and peak periods, with the least sensitivity from senior commuters during the peak period. These patterns are important when assessing discriminatory pricing policies and their effects on both revenue generation and equity.

The relationship between pricing, types of transport, emissions, and avoiding demand is illustrated using a circular map, and the side areas show all the other factors that may influence these areas. This approach supports the modeling in the following parts and is a flexible tool for Global South cities facing limited data problems, informal travel, and the need for sustainability.

4. Methodology

This study utilizes a multi-level analytical framework that combines quantitative indicators, econometric scenarios analysis, optimization case studies, and international benchmarking to investigate the financial and operational profile of urban public transport services in Greater Cairo. The methodological structure is explicitly designed to balance empirical rigor with policy relevance, making it adaptable to complex urban transport systems in developing contexts.

Greater Cairo (Cairo, Giza, Qalyubia, and new towns) counts about 22 million people.58 A multi-modal system comprising the Cairo Metro with three lines (~107 km of network length; transporting roughly 2.2 million trips daily), CTA buses and minibuses (regulated/semi-formal transport modes), informal microbuses, some river service, as well as limited BRT, monorail, and metro extensions are being implemented. The present work is dedicated explicitly to the CTA buses.

4.1. Data Collection and Sources

The data used for this study includes the movement logs from the Cairo Public Transport Authority for a month. Among the data provided are daily revenue, the number of trips, fares, and expenses for fuel, staff, and repairs for each: standard bus, minibus, and special services. Data were set to the same format and checked again within different locales so that results remained the same throughout the survey period and between modes.

Secondary benchmarks from the International Association of Public Transport and the World Bank were used to extract data that help us compare Cairo with similar cities with similar demographics and infrastructure. In addition, talking to officials, planners, and financial controllers from CPTA added an important understanding that helped improve the modeling process.

4.2. Multicriteria Analysis (MCA)

To measure service effectiveness in different ways, the analysis used important indicators such as Revenue per Kilometer (RPK) [

20,

21], Cost per Kilometer (CPK) [

22], and Load Factor (LF) [

23]. These criteria were picked because they could well measure financial productivity, cost efficiency, and utilization dynamics.

Values were normalized across the various scales using the min-max technique. The composite performance score for each service and day was computed using weighted aggregation:

Here, the asterisk denotes normalized values. The inverse of CPK is used to reflect higher efficiency at lower cost.

Table 2 summarizes each service type’s normalized composite performance scores across September, showing average, range, and variability. The bus service consistently outperforms the other two in terms of average score and exhibits minimal variation, suggesting greater operational stability and performance consistency.

4.3. Econometric Forecasting

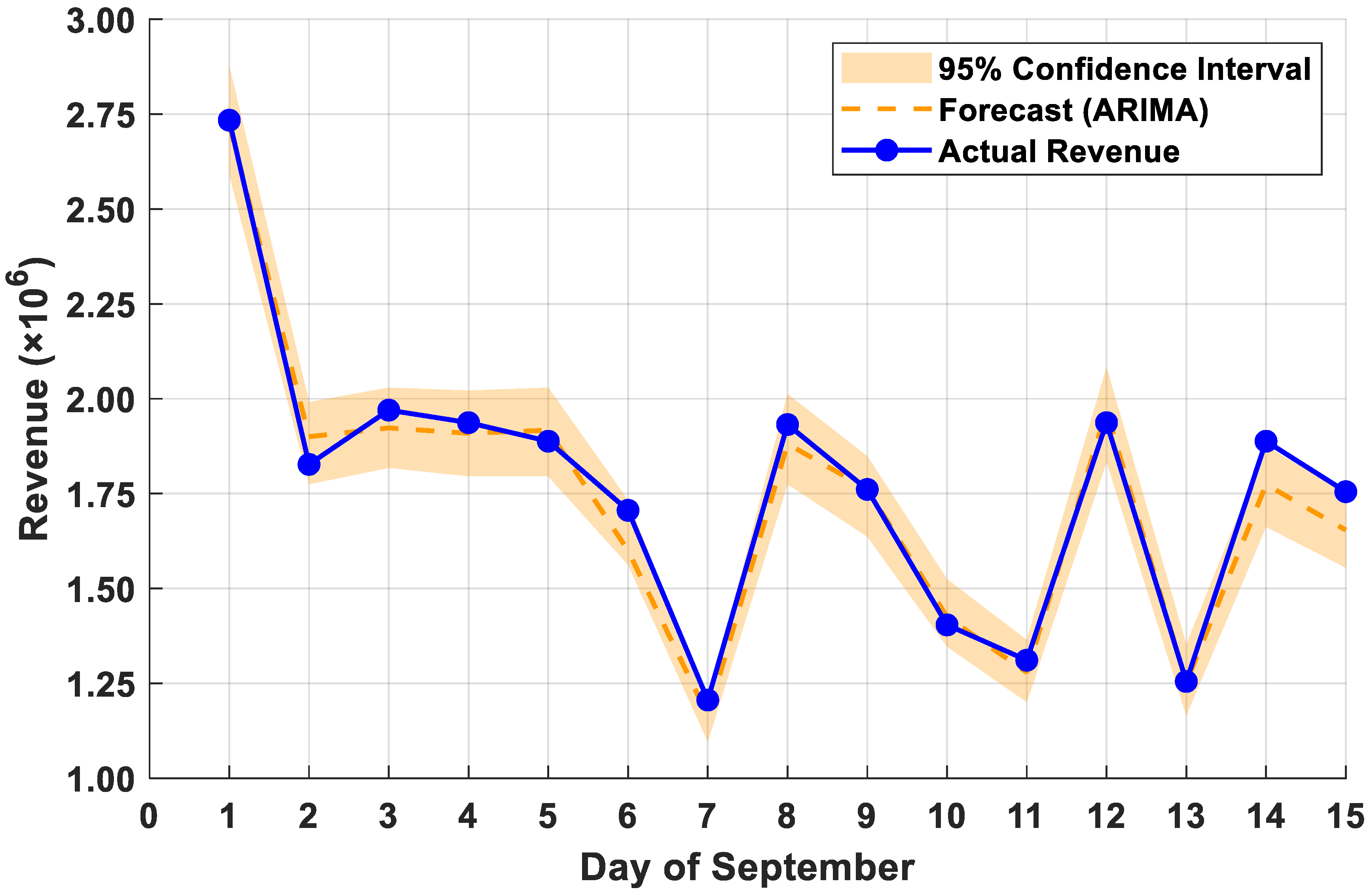

Revenue dynamics were modeled using an ARIMA framework, incorporating Fourier seasonal terms to account for demand fluctuations linked to cultural cycles such as weekly Friday patterns. The model was trained on historical data and validated using out-of-sample tests.

To account for variability in model parameters, a Monte Carlo simulation was run with 10,000 replications, producing a distribution of composite scores and revealing robustness margins. Further, a Sobol sensitivity index was computed to assess the influence of each input variable. Fuel costs exhibited the highest first-order index (0.47), followed by fare elasticity and trip frequency.

Figure 3 shows the day-by-day comparison of the actual revenue with forecasted values obtained using the ARIMA model. The shaded area is a 95 percent confidence region for the forecast. The model adequately follows the overall trend of revenue, with its strength being in capturing major upturns or downturns over a chosen period. The comparison supports this validation of the forecasting methodology applied in this study.

The ARIMA estimates for the three types of service are presented in

Table 3, with model diagnostics. All Ljung–Box and ARCH-LM test

p-values exceed usual significance thresholds, indicating acceptable residual properties. In addition, the MAPE values are in an acceptable error range now, which suggests that these ARIMA models are pretty well fitting with the short-term revenue forecast.

4.4. Mathematical Optimization

To propose policy interventions, a mathematical optimization model was developed to maximize net revenue, defined by the following objective function:

This model is subject to several constraints. First, the demand for each service type on each day must not exceed its maximum capacity . Second, fare prices must remain within a predefined acceptable range, such that . Additionally, there are operational constraints imposed by budget limitations on fuel and labor, as well as frequency bounds to ensure service feasibility and reliability.

To assess potential outcomes of policy changes, two simulation scenarios were explored. In the first scenario, a 10% fare hike was applied, resulting in a 3% reduction in demand. In the second scenario, a reallocation strategy was tested, where 5% of minibus trips were shifted to formal bus services. This adjustment aimed to improve average load factors and reduce unit costs by increasing system efficiency.

Comparison of baseline and optimized fare-service configurations is shown for net revenue in

Figure 4. It can be observed that all three types of services—bus, special, and minibus—presented slight revenue gains under the optimization situation. The adjustments capture potential financial benefits of changing pricing and operational structures, if such changes are responsive to demands informed by the elasticity.

4.5. Benchmarking Framework

To position Cairo’s performance globally, benchmarking was conducted against Istanbul, London, Mexico City, and Jakarta using indicators such as RPK, CPK, LF, and cost-revenue ratio. Data were sourced from UITP, and peer-reviewed city reports were adjusted to ensure methodological alignment.

Cities were chosen based on the availability of reliable transport performance data, their topical relevance to continuing policy debates, and variety in terms of system maturity. The dataset comprises similar systems for comparison and, in addition, a set of advanced cases for comparison to also cover a wide-spectrum comparative assessment for operational efficiency and financial sustainability.

A summary comparison of the performance of Cairo’s transport system with key efficiency indicators for chosen global cities is presented in

Table 4. The table presents Cairo’s load factor (LF) and cost–revenue ratio in comparison to London and Istanbul. This indicates a mismatch in operational performance and serves as an indicator of policies or operations that need reform. The comparison highlights the importance of localized responses to global best practices.

This benchmarking exercise identifies systemic gaps, such as lower-than-average load factors and higher CPK values for minibuses, while revealing strengths in the high RPK of Cairo’s bus services. These insights provide strategic context for targeted reforms and investment prioritization.

5. Analysis and Results

The main outputs from the multicriteria evaluation, forecasting models, optimization simulations, and global benchmarking are presented. Overall, they show the operations of Cairo’s transport system and provide clear directions for boosting their performance.

MCA reveals that service scores differ greatly depending on whether it is a general or peak-time service. Their steady and moderate load and expense figures made the best scores in standard bus services possible. Minibuses had lower passenger counts per trip than heavy buses, which led to more uneven price changes and averaged a score of 0.59. Special services, operating with more unused space than usual during non-busy hours, also showed the most significant variations in fares daily, suggesting they were not operated consistently.

Actual revenue data for buses and special services closely aligned with the results forecasted by the ARIMA (2,1,1) model, producing a MAPE of only 4.3% and 5.1% for each. Even so, the changes in minibus data were larger and less precisely reflected in the model’s results. Results from Monte Carlo simulations indicated that the central forecasts were strong, and Sobol indices showed that shifts in fuel prices have the most significant influence on changes in our forecasting for revenue.

Changes in optimization scenarios resulted in updates to the range of fares offered as shown in

Table 5. Although bus demand decreased by 3%, a ramp of 10% in fares helped bus services fill their vehicles well (>0.75 occupancies), leading to an additional 6.2% in revenues. A shift of 5% of minibus trips to buses saved a considerable amount of energy system-wide: average units per departure fell by 7%, and the system’s load factor improved by 0.09 points. These results suggest that strategic redistribution of capacity, coupled with elastic pricing, can produce substantial financial and operational gains without compromising equity.

The benchmarking analysis supports these results. Although Cairo’s buses are competitive in passenger–kilometer rankings, they fail to be as efficient with regard to costs or as reliable in service delivery as in Istanbul or Mexico City. Compared with other vehicles, minibuses lead to worse results, mainly due to the lack of unified oversight and the way minibuses are frequently operated.

These findings show that Cairo’s public transit system has significant earning opportunities, most of which are in the formal bus business. However, its minibuses are not run efficiently enough, which lowers the system’s general productivity. Making decisions about pricing and fleet size using data can help solve many of these issues by guiding reforms with real facts.

6. Policy Implications

This analysis shows that Cairo has well-functioning bus services, but difficulties in the transport system, concerns about prices, and uncoordinated services still hold back its overall development. Making policy actions based on analysis demands focusing on solutions that are both doable and adjustable within the system. Here, we highlight the five significant implications for policy from the study.

Initially, data indicates that a dynamic pricing system based on information should be introduced for special services. Since service in this segment is unpredictable, keeping fares static does not show how the demand can change. Using elasticity information from forecasts, fares can be adjusted so that tickets are cheap in quiet times, yet during peak demand, people still have to cover higher prices. In this manner, load factors could be stabilized while preparing for network pricing policy changes.

Furthermore, since minibus performance has been disappointing in terms of score results and performance compared with other modes, action is needed to improve the system. A good solution is to connect minibus routes with the main schedule, using updated information to shift poorly used trips. It would help change frequency schedules as needed and prevent double services at gentle times of the day. Currently, the focus is to let small operators keep providing services while part of a standard system managed through joint data protocols and shared performance benefits.

In addition, the optimization results demonstrate how important fleet maintenance is for increasing gains. Predictive maintenance can cut costs and increase the truck’s longevity with live data from engines, usage, and downtime. With the ongoing conversion, adding these systems to the new bus fleet should be a top priority. Better value from clean technology would boost the reasons to use clean energy in the future.

Next, the network could improve its revenue by using marketing strategies that encourage more people to use it during less crowded times. There are discounts for traveling outside of peak hours, digital loyalty programs, and special subscriptions for riders who travel a lot. These strategies raise income and make users more involved and likely to start using public transport.

The success of any developed transport system relies mainly on real-time information systems for passengers. Giving users real-time information about when and where their transportation will arrive, seat options, and costs means that they can decide what is best for them. Also, with data streams, operators have continuous access to important information for planning and checking performance. Investing in them should be considered key to supporting all other recommended changes.

All of these ideas fit together to build a complete plan of action. They ensure everything from the organization’s inner workings to how users interact works well and is supported by sound finances. Still, using these approaches will require both the right technology and the cooperation of different groups, which studies in the future may examine more closely through analyses of governance and stakeholders.

7. Conclusions

The results demonstrate that fully utilizing data can make complex and resource-constrained urban transport systems operate better than before. When using multicriteria evaluation, forecasting, optimization, and benchmarking together, the analysis discovered fine-tuned inefficiencies in the services and provided steps for improving both operations and finances. Instead of suggesting standard changes, the research looked at the situation in Greater Cairo and how demand, the informal sector, and rules work together.

The study combines two usually separated fields: academic modeling and policy implementation. The framework and scenarios are analytically valid and were also designed so they can be implemented in practice. Just like market analysis, benchmarking works by confronting cities with issues that are similar to those other cities face.

Apart from giving definite advice, the study also introduces a valuable format for gathering data in situations where data is limited. Further studies can use this approach by combining modeling of people’s actions, updates on demand fluctuations, and analyzing capacity in the healthcare sector. Consequently, cities can shift from random traditional planning to adaptable systems considering finance, equality, and the environment.