Scenarios of Automated Mobility in Austria: Implications for Future Transport Policy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Development of the Scenarios

3.1.1. Influencing Factors

3.1.2. Key Factors

3.1.3. Projections

3.1.4. Raw Scenarios and Reflection of Raw Scenarios

3.2. Modeling the Impacts of the Scenarios on the Transportation System

3.2.1. Approach for Modeling Transportation Impacts of the Scenarios

3.2.2. Adaptation of MARS and Implementation of Scenarios

4. Scenarios of Automated Mobility in Austria

4.1. Scenarios

5. Impacts of the Scenarios on the Austrian Transportation System

5.1. Implementation of Scenarios in MARS Model

5.2. Impacts of Scenarios

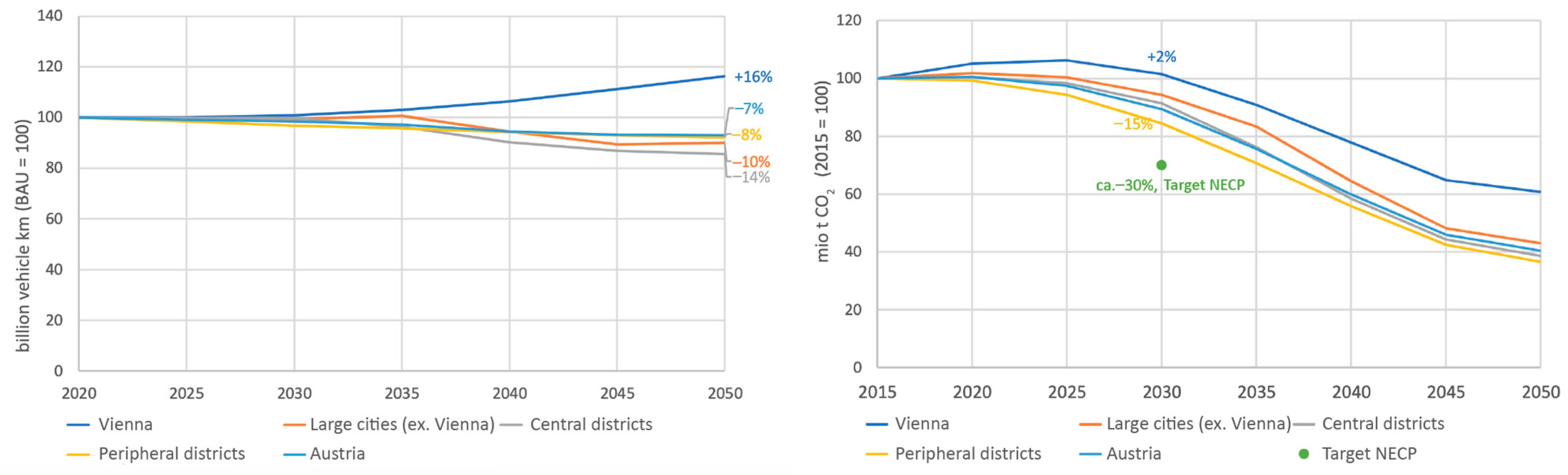

5.2.1. Scenario 1: Market-Driven AV Euphoria

5.2.2. Scenario 2: Policy-Driven AV Governance

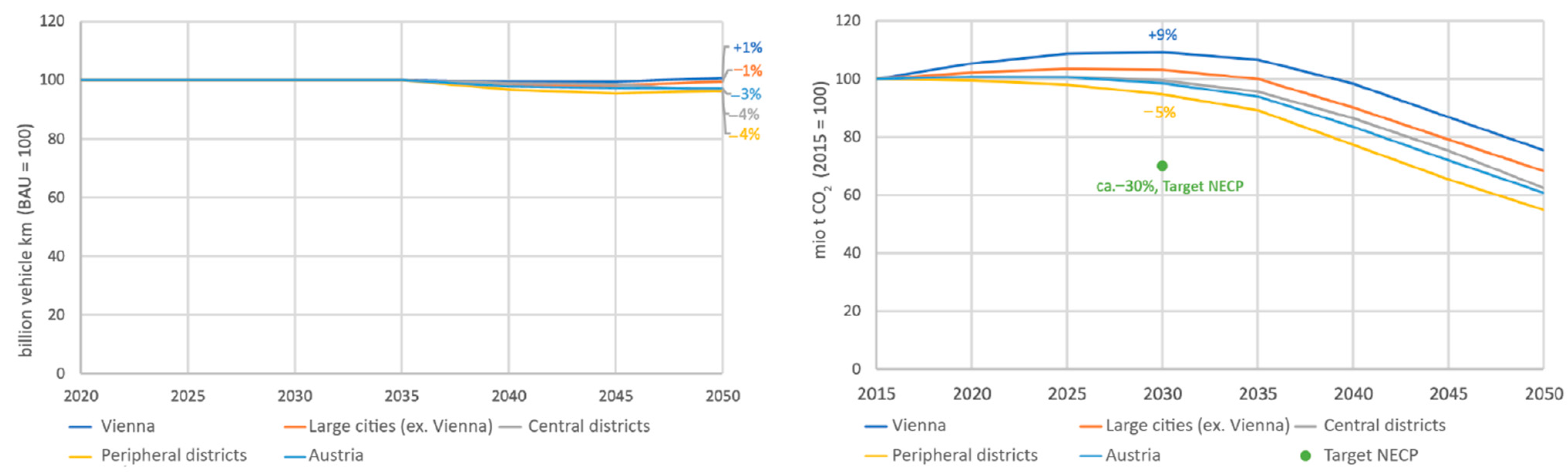

5.2.3. Scenario 3: Individualized Mobility and Slow AV Development

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Policy Implications

6.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Overview of Key Factors of Scenarios Used in Former Studies

| Authors, Country | Key Factors of Scenarios |

|---|---|

| Beiker, 2015 [47] | Automation (partial/conditional/high/full), area boundaries (none/regional/local), use (individual/private/public), ownership (individual/private/central/commercial). |

| Tillema et al., 2015 [19], Netherlands | Degree of vehicle automation (level 3, 4 or 5). Extent of vehicle sharing (high or low). |

| Gertz & Dörnemann, 2016 [48], Germany | Framework conditions for autonomous services (promoting or inhibiting framework conditions), mobility behaviour of residents (collective or individual). |

| Milakis et al., 2017 [49], Netherlands | Political regulation with regard to automated driving (restrictive or supportive), technological development (high or low). |

| Perret et al., 2017 [50], Switzerland | Storyline based on fulfilled requirements regarding legal, technological, infrastructural and societal aspects. |

| Mitteregger et al., 2020 [51] | Political planning stance: market-driven, policy-driven, community-driven. |

Appendix B. Example for the Developed Projections for the Key Factor Mobility as a Service

| Projection 1 | Projection 2 | Projection 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Dominance of local MaaS services of private companies (individual providers, weak interfaces to partner services and public transport) | Urban-regional public MaaS (increased cooperation between providers, expansion of public platforms) | No implementation of MaaS |

Appendix C. Example for the Consistency Analysis

Appendix D. Comparative Overview of the Scenarios

Scenario 1: Market-Driven AV euphoria | Scenario 2: Policy-Driven AV governance | Scenario 3: Individualized Mobility and Slow AV Development  | |

| Mobility and transport policy | Strong, active technology-driven AV policy focus on competitiveness and economy | Active environmental protection-driven AV policy focus on environmental sustainability and social inclusion | Strong, active technology-driven AV policy focus on competitiveness and economy |

| Mobility as a service (MaaS) | Dominance of local MaaS services of private companies individual providers, weak interfaces to partner services and public transport | Urban-regional public MaaS increased cooperation between providers, expansion of public platforms | No implementation of MaaS |

| Shared mobility | Car sharing spread of car sharing and leasing | Shared economy extensive spread of all forms of sharing: car sharing, ride sharing, etc. | No sharing no spread of sharing |

| Mobility attitudes | Euphoria extensive euphoria about AVs and sharing | Spatial ambivalence positive attitudes towards public transport and sharing in cities, positive attitudes towards private cars at most in sparsely populated places (automated and non-automated) | Polarization of society predominantly positive attitudes towards private cars (automated and non-automated), but low-income groups urged to use public transport |

| AV technology/artificial intelligence | Disruptive level 5 fully automated driving in (almost) all operational design domains, safety level worse than today | Fast level 4 highly automated driving in simple operational design domains, safety level better than today | Evolutionary level 3 conditional-automated driving in the simplest operational design domains, safety level somewhat lower than today |

| Propulsion technologies | Hybrid on the road high increase of hybrid drives/interim solutions | Electric mobility progress significant increase of electric vehicle registrations | Optimization of combustion engines status quo development for vehicles with alternative drives |

References

- SAE International. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles–J3016. 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3016_202104/ (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Sieber, M.; Stoiber, T.; Haefeli, U.; Matti, D. Forschungspaket Verkehr der Zukunft (2060): Initialprojekt; Forschungsprojekt SVI: Bern, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrend, C.; Kollosche, I.; Steinmüller, K.; Schulz-Montag, B. E-Mobility 2025. Szenarien für die Region Berlin. Szenarioreport; Technische Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gausemeier, J.; Fink, A.; Schlake, O. Szenario-Management; Planen und Führen mit Szenarien: Munich, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flämig, H. Autonomous vehicles and autonomous driving in freight transport. In Autonomous Driving; Maurer, M., Gerdes, C.J., Lenz, B., Winner, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandriz, T.; Jacobson, B.; Laine, L.; Hellgren, J. Impact of automated driving systems on road freight transport and electrified propulsion of heavy vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, M.; Mattas, K.; Ciuffo, B.; Raposo, M.A.; Thiel, C. Assessing the impact of connected and automated vehicles. A freeway scenario. In Microsystems for Automotive Applications 2017; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmassani, H.S. Autonomous vehicles and connected vehicle systems: Flow and operations considerations. Transp. Sci. 2016, 50, 1140–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteropoulos, A.; Berger, M.; Ciari, F. Impacts of automated vehicles on travel behaviour and land use: An international review of modelling studies. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, M.; Stathopoulos, A.; Shiftan, Y.; Walker, J.L. What do we (Not) know about our future with automated vehicles? Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 123, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafidis, P.; Farah, H.; Brijs, T.; Pirdavani, A. Safety implications of higher levels of automated vehicles: A scoping review. Transp. Rev. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D.; van Arem, B.; van Wee, B. Policy and society related implications of automated driving: A review of literature and directions for future research. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 21, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, M.; Schuhmayer, C.; Kummer, S. Innovation in mobility: Austrian expert’s perspective on the future of urban mobility with self-driving cars. In Innovation Arabia 9: Quality and Business Management Conference (Business Innovation-Imperative for knowledge Economy); HBMSU Publishing House: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2016; Volume 9, pp. 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wintersberger, S.; Azmat, M.; Kummer, S. Are We Ready to Ride Autonomous Vehicles? A Pilot Study on Austrian Consumers’ Perspective. Logistics 2019, 3, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Schwall, M.; Daniel, T.; Victor, T.; Favaro, F.; Hohnhold, H. Waymo public road safety performance data. arXiv Prepr. 2020, arXiv:2011.00038. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, L.; Kuhnimhof, T.; Trommer, S. Does context matter? A comparative study modelling autonomous vehicle impact on travel behaviour for Germany and the USA. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 122, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelauff, G.; Ossokina, I.; Teulings, C. Spatial and welfare effects of automated driving: Will cities grow, decline or both? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 121, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, M.; Kummer, S.; Moura, L.T.; Gennaro, F.D.; Moser, R. Future outlook of highway operations with implementation of innovative technologies like AV, CV, IoT and Big Data. Logistics 2019, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tillema, T.; Berveling, J.; Gelauff, G.; van der Waard, J.; Harms, L.; Derriks, H. Driver at the Wheel? Self-Driving Vehicles and the Traffic and Transport System of the Future; KiM. Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart, C.E.; Müller, J.D.; Oppolzer, J. Delivering Tomorrow. Logistik 2050; Eine Szenariostudie. Deutsch Post AG: Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Phleps, P.; Feige, I.; Zapp, K. Die Zukunft der Mobilität. Szenarien für Deutschland in 2035; Ifmo—Institut für Mobilitätsforschung: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ScenarioWizard. Available online: http://www.cross-impact.org/english/CIB_e_ScW.htm (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Padlet. Available online: https://en.padlet.com/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Emberger, G.; Pfaffenbichler, P. A quantitative analysis of potential impacts of automated vehicles in Austria using a dynamic integrated land use and transport interaction model. Transp. Policy 2020, 98, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Redl, C.; Haas, R.; Tuerk, A.; Liebmann, L.; Steininger, K.; Brezina, T.; Mayerthaler, A.; Kreuzer, D.; Steiner, A.; et al. Energy Investment Strategies and Long Term Emission Reduction Needs (EISERN); Technische Universität Wien Institut für Energiesysteme und Elektrische Antriebe: Vienna, Austria, 2012; Available online: https://www.fvv.tuwien.ac.at/fileadmin/mediapool-verkehrsplanung/News/EISERN/m%C3%BCller-2012_EISERN-Endbericht.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Hanika, A. Kleinräumige Bevölkerungsprognose für Österreich 2010–2030 mit Ausblick bis 2050-Teil 1: Endbericht zur Bevölkerungsprognose. Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK); Statistik Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hanika, A. Kleinräumige Bevölkerungsprognose für Österreich 2010–2030 mit Ausblick bis 2050-Teil 3: Endbericht zu den Modellrechnungen zur regionalen Haushaltsentwicklung. Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK); Statistik Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kytir, J.; Biffl, G.; Wisbauer, A. Kleinräumige Bevölkerungsprognose für Österreich 2010–2030 mit Ausblick bis 2050-Teil 2 Endbericht zur Erwerbsprognose. Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK); Statistik Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krutzler, T.; Zechmeister, A.; Stranner, G.; Wiesenberger, H.; Gallauner, T.; Gössl, M.; Heller, C.; Heinfellner, H.; Ibesich, N.; Lichtblau, G. Energie- und Treibhausgas-Szenarien im Hinblick auf 2030 und 2050; Umweltbundesamt: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heinfellner, H.; Ibesich, N.; Lichtblau, G.; Svehla-Stix, S.; Vogel, J.; Wedler, M.; Winter, R. Sachstandsbericht Mobilität und mögliche Zielpfade zur Erreichung der Klimaziele 2050 mit dem Zwischenziel 2030; Endbericht. Umweltbundesamt: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Umweltbundesamt Emissionsfaktoren für Verkehrsmittel. Umweltsituation-Verkehr-Daten. 2018. Available online: http://www.umweltbundesamt.at/umweltsituation/verkehr/verkehrsdaten/emissionsfaktoren_verkehrsmittel/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Beermann, M.; Lorenza, C.; Jungmeier, G. Transportdienstleistung von E-Fahrzeugen in Österreich Zielsetzung; Symposium Energieinnovation: Graz, Austria, 2012; Available online: https://www.tugraz.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Events/Eninnov2012/files/pr/PR_Beermann_2.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Pfaffenbichler, P. The Strategic, Dynamic and Integrated Urban Land Use and Transport Model MARS (Metropolitan Activity Relocation Simulator)-Development, Testing and Application; Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffenbichler, P.C.; Emberger, G.; Shepherd, S.P. A system dynamics approach to land use transport interaction modelling: The strategic model MARS and its application. Syst. Dynam. Rev. 2010, 26, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Transport Planning and Traffic Engineering. MARS (Metropolitan Activity Relocation Simulator). Available online: https://www.fvv.tuwien.ac.at/forschung/mars-metropolitan-activity-relocation-simulator/overview/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Bösch, P.M. Kapazitätsauswirkungen vollautonomer Fahrzeuge in der Schweiz. 26; PTV Traffic Seminar: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bösch, P.M.; Becker, F.; Becker, H.; Axhausen, K.W. Cost-based analysis of autonomous mobility services. Transp. Policy 2018, 64, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteropoulos, A.; Stickler, A.; Sodl, V.; Berger, M.; Dangschat, J.; Pfaffenbichler, P.; Emberger, G.; Frankus, E.; Braun, R.; Schneider, F.; et al. SAFiP -Systemszenarien Automatisiertes Fahren in der Personenmobilität; Forschungsbericht: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. Automotive Revolution—Perspective towards 2030. How the Convergence of Disruptive Technology-Driven Trends Could Transform the Auto Industry. 2016. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/automotive%20and%20assembly/our%20insights/disruptive%20trends%20that%20will%20transform%20the%20auto%20industry/auto%202030%20report%20jan%202016.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Busch, F.; Krause, S.; Motamedidehkordi, N.; Hoffmann, S.; Vortisch, P.; Hartmann, M. Auswirkungen des teil- und hochautomatisierten Fahrens auf die Kapazität. Fernstraßeninfrastruktur; Verband der Automobilindustrie, Forschungsvereinigung Automobiltechnik: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, C.J.; Eisenberger, I.; Fellendorf, M.; Gruber, C.; Kohla, B.; Lachmayer, K.; Neuhold, R.; Röschel, G.; Sammer, G.; Sammer, G.; et al. Forschungsprojekt AUTO-NOM Analyse, Evaluierung und Anforderungen an innovative Anwendungen von autonomen Fahrzeugen aus verkehrspolitischer Sicht-Teil 1: Verkehrliche Auswirkungen und verkehrspolitische Aussagen; Mobilität der Zukunft: Graz, Austria, 2018; Available online: https://mobilitaetderzukunft.at/resources/pdf/projektberichte/AUTO-NOM_2017_Teil1_Verkehrliche_Auswirkungen_und_verkehrspolitische_Aussagen_1101.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Wadud, Z.; MacKenzie, D.; Leiby, P. Help or hindrance? The travel, energy and carbon impacts of highly automated vehicles. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2016, 86, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krail, M.; Hellekes, J.; Schneider, U.; Dütschke, E.; Schellert, M.; Rüdiger, D.; Steindl, A.; Luchmann, I.; Waßmuth, V.; Flämig, H.; et al. Energie- und Treibhausgaswirkungen des automatisierten und vernetzten Fahrens im Straßenverkehr; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.isi.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/isi/dokumente/ccn/2019/energie-treibhausgaswirkungen-vernetztes-fahren.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Pfaffenbichler, P.; Emberger, G. SAFiP-Systemszenarien Automatisiertes Fahren in der Personenmobilität—Deliverable 3.1; Institute for Transport Planning and Traffic Engineering: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Nachhaltigkeit und Tourismus. #mission2030. Die österreichischen Klima- und Energiestrategie. Vienna, Austria. 2018. Available online: https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/dam/jcr:903d5cf5-c3ac-47b6-871c-c83eae34b273/20_18_beilagen_nb.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Soteropoulos, A.; Mitteregger, M.; Berger, M.; Zwirchmayr, J. Automated Drivability: Toward an assessment of the spatial deployment of level 4 automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A 2020, 136, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiker, S. Einführungsszenarien für höhergradig automatisierte Straßenfahrzeuge. In Autonomes Fahren; Maurer, M., Gerdes, C.J., Lenz, B., Winner, H., Eds.; Springer Vieweg: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gertz, C.; Doörnemann, M. Wirkungen des autonomen/fahrerlosen Fahrens in der Stadt. Entwicklung von Szenarien und Ableitung der Wirkungsketten; Bremen, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.bauumwelt.bremen.de/sixcms/media.php/13/_Wirkungen_autonomen_fahrerlosen%20Fahrens_in_der_Stadt%20.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Milakis, D.; Snelder, M.; van Arem, B.; van Wee, B. Homem de Almeida Correia, G. 2017. Development and transport im-plications of automated vehicles in the Netherlands: Scenarios for 2030 and 2050. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2017, 17, 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Perret, F.; Bruns, F.; Raymann, L.; Hofmann, S.; Fischer, R.; Abegg, C.; de Haan, P.; Straumann, R.; Heuel, S.; Deublein, M.; et al. Einsatz automatisierter Fahrzeuge im Alltag—Denkbare Anwendungen und Effekte in der Schweiz. EBP; Basler Fonds: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mitteregger, M.; Bruck, E.; Soteropoulos, A.; Stickler, A.; Berger, M.; Dangschat, J.S.; Scheuvens, R.; Banerjee, I. AVENUE21. Automatisierter und vernetzter Verkehr: Entwicklungen des urbanen Europa; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Steps | Description | Integration of External Experts and Stakeholders | |

|---|---|---|---|

Influencing factors |

|  | Input of external experts and stakeholders |

Key factors and cross-scenario factors |

|  | Input of external experts and stakeholders |

Projections |

| ||

Raw scenarios |

| ||

Final scenarios |

|  | Input of external experts and stakeholders |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Market share of level 4 and 5 AVs | Input assumptions on the vehicle fleet penetration of AVs (level 4 and 5). These assumptions were based on a market share study carried out by McKinsey & Company [39], entailing low- and high-disruption scenarios for level 4 and 5 AV market penetration. |

| Market share of electric vehicles | Input assumptions on the vehicle fleet penetration of electric vehicles. These assumptions were based on Krutzler et al. [29], entailing different scenarios for the vehicle penetration of electric vehicles in Austria. |

| AV ownership/business model | Input assumptions on the business model of AVs (AVs as private cars, car sharing with AVs, ride sharing with AVs), extension of user groups (no driving licences needed) and costs of using AVs. |

| Road capacity | Input assumptions on the impact of AVs on road capacity. Whereas, on the one hand, studies (e.g., [12,40,41]) assume that AVs can drive closer together and, therefore, the road capacity increases, on the other hand, some studies (e.g., [41]) conclude that there will be a reduction of travel speeds and an increase of travel time during off-peak because AVs must strictly adhere to traffic rules with regard to visibility, stopping distance, permissible maximum speed, etc. |

| Parking place search and egress time | Input assumptions about the impact of AVs for parking place search and egress time as AVs can just pick up the passengers at the entrance to their homes and drop them off in front of their destinations. |

| In-vehicle value of time (VOT) | Input assumptions on the impact of AVs on the in-vehicle value of time (VOT) as a variety of studies on automated driving (e.g., [41,42]) argue that the comfort gain with AVs will change the valuation of in-vehicle time. |

| Implementation of first/last mile AVs in public transport (share of population within 15 min of public transport stop) | Input assumptions on the intensity of implemented first/last mile AVs in public transport by assumptions and variations of the share of population living within a 15 min radius to public transport stops. |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

Scenario 1: Market-driven AV euphoria

| With the scenario “Market-driven AV euphoria”, a spread of au-tomated car sharing and leasing services with weak interfaces to public transport is sketched against the background of a mobility and transport policy geared especially towards competitiveness and economic development, as well as a great progress in automa-tion technologies and sharing by the population. Most people in Austria travel with hybrid drives. |

Scenario 2: Policy-driven AV governance

| In the scenario “Policy-driven AV governance”, against the background of a mobility and transport policy oriented towards ecological sustainability and social inclusion and the use of highly automated vehicles in simple operational design domains, an extensive spread of all forms of sharing as well as an important role of public transport and active mobility in Austria is described. These transport services are largely integrated into urban-regional public mobility services (MaaS). Electric vehicles are widespread due to technological progress (shorter charging times, extended range) and falling battery prices. |

Scenario 3: Individualized mobility and slow AV development | In the scenario “Individualized mobility and slow AV development”, against the background of a mobility and transport policy geared especially towards competitiveness and economic development, as well as only slight progress in automation technologies, it is assumed that motorized individual transport will continue to be widespread in Austria, while public transport or ride sharing services will hardly prevail and are regarded as rather insecure. Electric vehicles are not very attractive—mainly due to their short range, a high charging time and high purchase costs. |

| Parameter | BAU: Business as Usual | Scenario 1: Market-Driven AV Euphoria | Scenario 2: Policy-Driven AV Governance | Scenario 3: Individualized Mobility and Slow AV Development | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market share of level 4 and 5 AVs | 2020 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2025 | 0% | 7% | 4% | 0% | |

| 2030 | 0% | 22% | 14% | 0% | |

| 2035 | 0% | 55% | 29% | 4% | |

| 2040 | 0% | 72% | 44% | 7% | |

| 2045 | 0% | 85% | 68% | 22% | |

| 2050 | 0% | 92% | 85% | 55% | |

| Market share of electric vehicles | 2020 | 3% | 4% | 5% | 3% |

| 2025 | 7% | 9% | 12% | 7% | |

| 2030 | 14% | 23% | 31% | 14% | |

| 2035 | 23% | 41% | 57% | 23% | |

| 2040 | 35% | 58% | 82% | 35% | |

| 2045 | 50% | 75% | 98% | 50% | |

| 2050 | 63% | 82% | 99% | 63% | |

| AV ownership/business model | Business model | Car sharing with AVs | Ride sharing with AVs | AVs as private cars | |

| User group extension for AVs | No extension (18 year olds or older with driving licence, living in household with car) | 15–17 year olds and persons without driving licences (including disabled and elderly), all households | 15–17 year olds and persons without driving licences (including disabled and elderly), all households | 15–17 year olds and persons without driving licences (including disabled and elderly) living in household with AVs | |

| AV occupancy rate | 1.05 | 1.26 | 1.05 | ||

| Empty load share | +5% | +5% | no change | ||

| Detour factor | 0 | +5% | 0 | ||

| Cost per person km | 55 cent/km | 55 cent/km | no change | ||

| Road Capacity | Urban roads | no change | Peak: −5%; Off-peak: +7% | ||

| Interurban roads | no change | Peak: −10%; Off-peak: +5% | |||

| Motorways | no change | Peak: −15%; Off-peak: +13% | |||

| Parking place search time | Level 4 and 5 AVs | Reduction to 0 | |||

| In-vehicle VOT | Level 4 and 5 AVs | −20% | |||

| Implementation of first/last mile AVs in public transport(share of population within 15 min of public transport stop) | Vienna | 97% | 97% | 100% | 97% |

| Urban | 72% | 80% | 90% | 80% | |

| Suburban | 32% | 60% | 75% | 60% | |

| Rural (good PT service) | 22% | 30% | 50% | 30% | |

| Very rural (poor PT service) | 10% | 30% | 50% | 30% | |

| Scenario | Indicator | Year | Walking | Bicycle | PT | Car | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: Market-driven AV euphoria | Modal share-trips | 2030 | 13.9% | 7.2% | 15.4% | 63.4% | 100.0% |

| 2050 | 10.2% | 4.9% | 15.7% | 69.2% | 100.0% | ||

| Billion person-km | 2030 | 2.28 | 1.60 | 16.40 | 87.08 | 107.36 | |

| 2050 | 1.65 | 1.07 | 17.47 | 90.37 | 110.56 | ||

| Billion vehicle-km | 2030 | 66.40 | 66.40 | ||||

| 2050 | 72.66 | 72.66 | |||||

| Billion trips | 2030 | 1.03 | 0.53 | 1.14 | 4.69 | 7.39 | |

| 2050 | 0.75 | 0.36 | 1.16 | 5.08 | 7.34 | ||

| Million t CO2 | 2030 | 13.66 | |||||

| 2050 | 6.19 | ||||||

| Scenario 2: Policy-driven AV governance | Modal share-trips | 2030 | 14.2% | 7.3% | 16.9% | 61.5% | 100.0% |

| 2050 | 11.1% | 4.9% | 19.4% | 64.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Billion person-km | 2030 | 2.25 | 1.57 | 18.45 | 82.47 | 104.73 | |

| 2050 | 1.63 | 0.96 | 21.43 | 83.44 | 107.47 | ||

| Billion vehicle-km | 2030 | 62.74 | 62.74 | ||||

| 2050 | 64.30 | 64.30 | |||||

| Billion trips | 2030 | 1.01 | 0.52 | 1.20 | 4.38 | 7.12 | |

| 2050 | 0.74 | 0.32 | 1.29 | 4.31 | 6.66 | ||

| Million t CO2 | 2030 | 11.80 | |||||

| 2050 | 3.09 | ||||||

| Scenario 3: Individualized mobility and slow AV development | Modal share-trips | 2030 | 14.7% | 7.8% | 14.5% | 63.0% | 100.0% |

| 2050 | 11.3% | 5.5% | 15.8% | 67.4% | 100.0% | ||

| Billion person-km | 2030 | 2.49 | 1.78 | 15.50 | 88.68 | 108.45 | |

| 2050 | 1.86 | 1.22 | 16.10 | 97.83 | 117.01 | ||

| Billion vehicle-km | 2030 | 67.44 | 67.44 | ||||

| 2050 | 75.88 | 75.88 | |||||

| Billion trips | 2030 | 1.12 | 0.59 | 1.11 | 4.80 | 7.63 | |

| 2050 | 0.84 | 0.41 | 1.17 | 4.99 | 7.41 | ||

| Million t CO2 | 2030 | 15.05 | |||||

| 2050 | 9.28 | ||||||

| BAU: Business as usual | Modal share-trips | 2015 | 16.1% | 8.6% | 14.9% | 60.4% | 100.0% |

| 2030 | 14.7% | 7.8% | 14.5% | 63.0% | 100.0% | ||

| 2050 | 13.0% | 6.7% | 14.0% | 66.3% | 100.0% | ||

| Billion person-km | 2015 | 2.42 | 1.75 | 15.57 | 79.74 | 99.48 | |

| 2030 | 2.49 | 1.78 | 15.50 | 88.68 | 108.45 | ||

| 2050 | 2.26 | 1.59 | 14.09 | 102.57 | 120.52 | ||

| Billion vehicle-km | 2015 | 60.85 | 60.85 | ||||

| 2030 | 67.44 | 67.44 | |||||

| 2050 | 78.05 | 78.05 | |||||

| Billion trips | 2015 | 1.09 | 0.58 | 1.01 | 4.10 | 6.78 | |

| 2030 | 1.12 | 0.59 | 1.11 | 4.80 | 7.63 | ||

| 2050 | 1.02 | 0.53 | 1.10 | 5.22 | 7.87 | ||

| Million t CO2 | 2015 | 15.28 | |||||

| 2030 | 15.05 | ||||||

| 2050 | 9.54 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soteropoulos, A.; Pfaffenbichler, P.; Berger, M.; Emberger, G.; Stickler, A.; Dangschat, J.S. Scenarios of Automated Mobility in Austria: Implications for Future Transport Policy. Future Transp. 2021, 1, 747-764. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp1030041

Soteropoulos A, Pfaffenbichler P, Berger M, Emberger G, Stickler A, Dangschat JS. Scenarios of Automated Mobility in Austria: Implications for Future Transport Policy. Future Transportation. 2021; 1(3):747-764. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp1030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoteropoulos, Aggelos, Paul Pfaffenbichler, Martin Berger, Günter Emberger, Andrea Stickler, and Jens S. Dangschat. 2021. "Scenarios of Automated Mobility in Austria: Implications for Future Transport Policy" Future Transportation 1, no. 3: 747-764. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp1030041

APA StyleSoteropoulos, A., Pfaffenbichler, P., Berger, M., Emberger, G., Stickler, A., & Dangschat, J. S. (2021). Scenarios of Automated Mobility in Austria: Implications for Future Transport Policy. Future Transportation, 1(3), 747-764. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp1030041