2. Materials and Methods

This is a methodological study with a technological focus and a quantitative approach. The Unified Process (UP) methodology model was used, based on the Rational Unified Process (RUP) strategy.

The Unified Process model served as a guide for the study stages and consists of four distinct phases: conception, elaboration, construction, and transition [

8,

9]. The conception phase aims to establish an understanding of the project’s scope in order to achieve a high-level understanding of the requirements to be addressed [

8]. The elaboration phase encompasses the structure of the MLP ANN to indicate the appropriate coverage for the treatment of venous ulcers. The development phase involves the construction and implementation of the MLP ANN, including tests and evaluation of the intelligent software. The fourth and final phase is the transition, in which the software is finalized.

2.1. Phase 1—Conception

For the first phase, the nursing researcher presented the problem to the computing professional: “How can the nurse be assisted in decision-making when choosing dressings for the treatment of venous ulcers through an Artificial Neural Networks?” The information needed to function as variables and/or requirements for the network was then gathered.

Initially, an integrative literature review was conducted with the aim of identifying scientific evidence regarding the dressings used in the treatment of venous ulcers.

Next, three expert judges were consulted to collect information on the topical therapies used in their clinical practices for the care of venous ulcers. An odd number (three) was chosen to avoid ties during the responses. A convenience sample was selected, with the following inclusion criteria: nursing professionals who were experts in wound treatment and had five or more years of professional experience in nursing and/or had specialization in Dermatological Nursing or Ostomy Care Nursing.

The judges at this stage were used only to show that the practice corroborates the information already contained in manuals, protocols and literature already developed, not seeking validation, so the number of three experts is acceptable.

The judges were invited, and after agreeing to participate, they were sent a link to access the Informed Consent Form (ICF) and a questionnaire containing both open-ended and closed-ended questions, divided into two parts. The first part aimed at characterizing the participants (gender, institution, age, education, qualifications, years of experience in clinical care, and/or years of experience in teaching). In the second part, the participants identified the clinical characteristics present in the ulcer and provided suggestions for dressings for the wounds.

This part consisted of eight (8) clinical cases, each with an image of a venous ulcer, containing three (3) questions for each case. The questions were related to risk factors, choice of antiseptics for the wound, and prescription of the topical dressing, totaling 24 questions.

The data collection took place in May 2022, and the judges were given a 30-day deadline to return the evaluated instruments.

After conducting the integrative literature review and consulting the expert judges, the dressings used in the topical treatment of venous ulcers and their respective clinical indications were identified. This step was necessary to ensure the requirements aligned with the objectives of the technological development. These data were used as input and output requirements for the convolutional neural network and were subsequently provided to the information technology professionals to be integrated into the software.

The clinical indications were based on the Red/Yellow/Black protocols [

9], TIMERS [

10], and the wound evaluation triangle [

11]. These protocols provided information on the color and type of tissue, the amount and type of exudate, odor, and infections. These data were used as input for the intelligent classifier.

2.3. Phase 3—Construction/Evaluation/Validation

In this phase, the network MLP development/implementation took place, along with software testing and evaluation. The software tests were conducted to identify errors, issues, or defects during its development. This step is necessary to verify if the software is functioning properly and accurately.

The network construction was performed by computing professionals, based on the information provided by the researcher (nurse), derived from the responses given by the judges during the validation phase, as well as from the literature review and protocols. After the network construction and testing were completed, an evaluation was conducted with nurses to determine whether the software could assist in decision-making regarding dressings for venous ulcers.

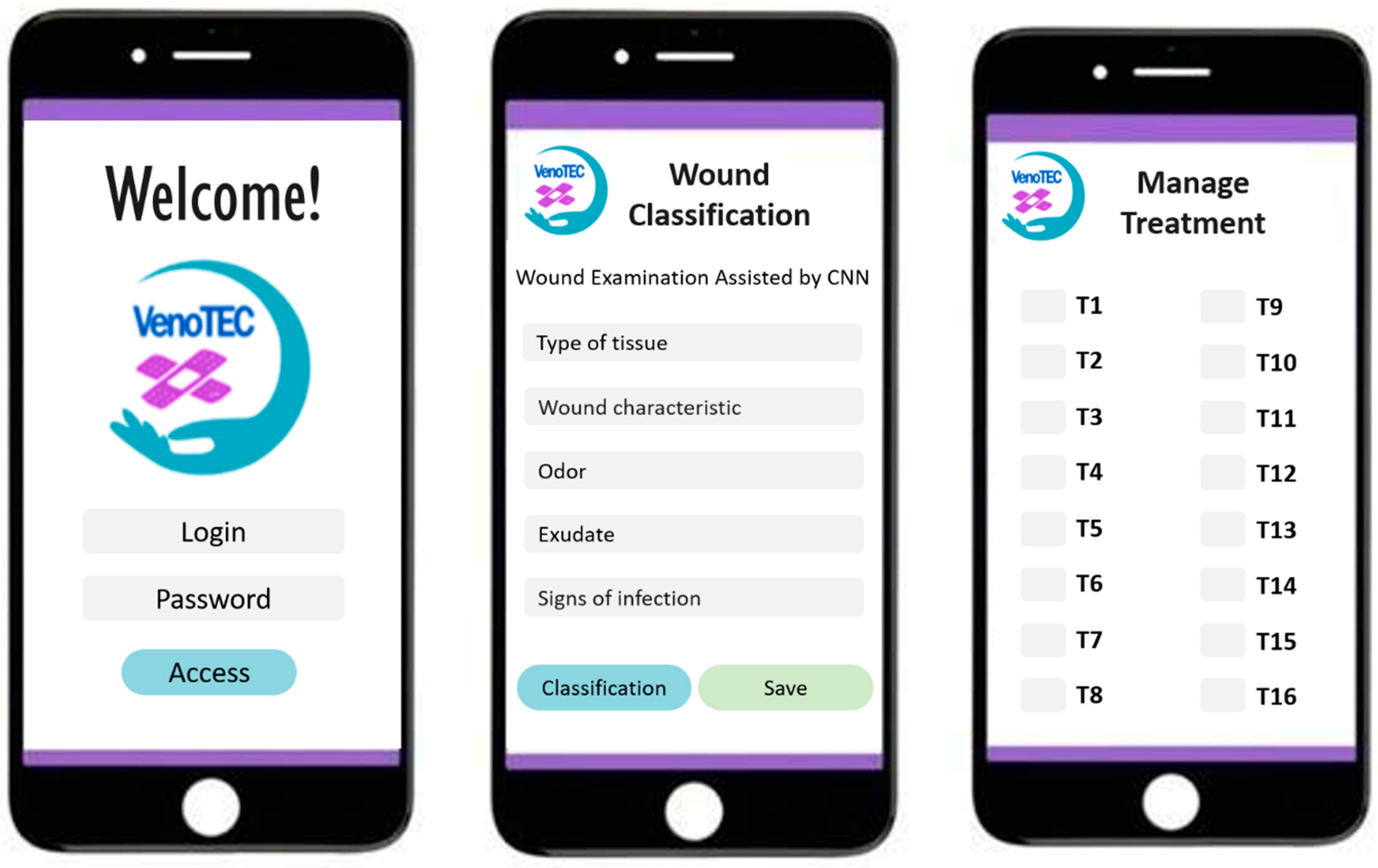

In this context, usability evaluation followed. For this, it was necessary to create a web-based app with artificial intelligence to facilitate the use of the neural network capable of suggesting dressings for the user. The app was named VenoTEC.

For usability evaluation, the sample consisted of 13 nurse judges. An odd number of judges was chosen to avoid ties, and they were selected based on the following criteria: nurses with experience in wound care; nurses with one (1) or more years of professional experience in nursing; and nurses involved in the care of individuals with venous ulcers.

An email was sent explaining the purpose of the specialist’s participation and an invitation letter. After agreeing to participate, the participants received the link to access the Informed Consent Form (ICF), the web app (with the developed software), and the electronic questionnaire, as well as instructions for using the app via an illustrative video.

Data collection took place in June 2022. The questionnaire contained two parts: the first part focused on the participants’ characterization data (gender, institution, age, education, qualifications, years of experience in clinical care, and years of teaching experience), and the second part evaluated the software’s usability using the System Usability Scale (SUS), developed by John Brooke [

12]. The scale consists of 10 questions rated on a Likert-type scale, with values ranging from one to five, classified as “strongly disagree,” “disagree”, “neutral”, “agree”, and “strongly agree.” Half of the statements are phrased positively, while the other half are phrased negatively. The contribution of each item is scored from 0 to 4. For items 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, the score contribution is the scale position marked by the participant minus one. For items 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, the score contribution is 5 minus the marked position. The sum of the scores is multiplied by 2.5 to obtain the overall scale score. Based on the score and the calculation of the SUS score, the SUS can be classified as follows: scores below 50 points indicate very poor usability, scores between 51 and 64 indicate poor usability, scores between 65 and 74 indicate neutral usability, scores of 75 or above indicate good usability, and scores of 80 or above indicate very good usability [

12].

Data analysis and interpretation were conducted after entering the data into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. After this process, the data were exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) 20.0 software, where they were analyzed using relative and absolute frequencies.

To minimize the risk of overfitting and ensure the robustness of the results, a rigorous validation protocol was implemented. Instead of a single split between training and testing, stratified five-fold cross-validation was adopted, a technique widely recognized for providing more stable and generalizable estimates of predictive model performance [

13,

14]. This approach ensures that the model is trained and evaluated on different data subsets, reducing the impact of sampling variations and increasing the reliability of the obtained metrics.

To avoid data leakage, considered a common bias in validation processes [

15], normalization of the predictor variables was applied exclusively to the training set for each fold and subsequently used to transform the remaining subsets. Furthermore, the early stopping technique was employed, recognized for its effectiveness in preventing overfitting during neural network training [

16].

Class balancing was achieved by assigning proportional weights (class weights) to prevent underrepresented categories from being underestimated in the learning process. Finally, to assess the statistical significance of the results, a permutation test with 200 permutations was applied to the accuracy metric, allowing us to estimate the probability that the observed performance occurred by chance and reinforcing the statistical validity of the experimental findings.

To assess the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), a comprehensive benchmark analysis was performed using several classical machine learning algorithms under identical experimental conditions. The models evaluated included Decision Tree, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Linear SVM, SVM with RBF kernel, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Gradient Boosting.

All models were trained and validated through a stratified 5-fold cross-validation protocol, with normalization applied exclusively to the training subset of each fold and preservation of the original class distribution. Evaluation metrics included Accuracy, F1-macro, and ROC-AUC (when available), complemented by permutation tests with 200 permutations to assess statistical significance.

3. Results

The development of the neural network involved the collaboration of three judges, all female, aged between 38 and 58 years. One was a PhD holder, one was a Master’s degree holder, and one was a specialist. All had specialization or residency in stomatherapy/dermatology, with training ranging from 9 to 35 years, and experience in the treatment of venous ulcers ranging from 8 to 25 years.

The judges assessed eight clinical cases and eight images of venous ulcers corresponding to each case. They identified the risk factors hindering wound healing and prescribed antiseptics and topical therapies. This step identified the coverings used by specialists in their clinical practice, which complement the list of coverings used in the artificial neural network, along with those found in the integrative review conducted for the study and in wound care protocols.

It is important to note that the barrier cream and physiological saline solution recommended by the judges were not included in the software. The barrier cream was excluded due to its recommendation for use on perilesional skin, and the saline solution was excluded as it is a wound cleaning product, while the network aims to suggest topical therapies for the wound bed, not antiseptics.

The Lipid Colloid Technology-Nano Oligosaccharide (TLC-NOSF), found in the articles of the review, was presented in the network MLP according to its form, either in foam or fiber, and including carboxymethylcellulose in the composition. This was due to the lack of details regarding other components of the technology in the analyzed articles.

As a result, 23 coverings were identified (

Table 1). Some coverings were excluded due to a lack of sufficient clinical efficacy evidence. These include Gel ACT1 and the 0.2% benzethonium chloride complex ointment, the Natural Matrix Biopolymer Membrane (NMBN) due to its primary function as an analgesic and lack of evidence of its association with other substances that promote healing; the 80% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution was excluded for its action on hypergranulation tissue, for not being part of the features that served as input data for the MLP network.

Additionally, the bromelain-enriched proteolytic enzyme concentrate was excluded due to instability in certain formulations, requiring controlled studies before it can be safely used in clinical practice. Lastly, fibrin and platelet gels were excluded because they were used in injectable form in studies, while this research focused only on topical therapies.

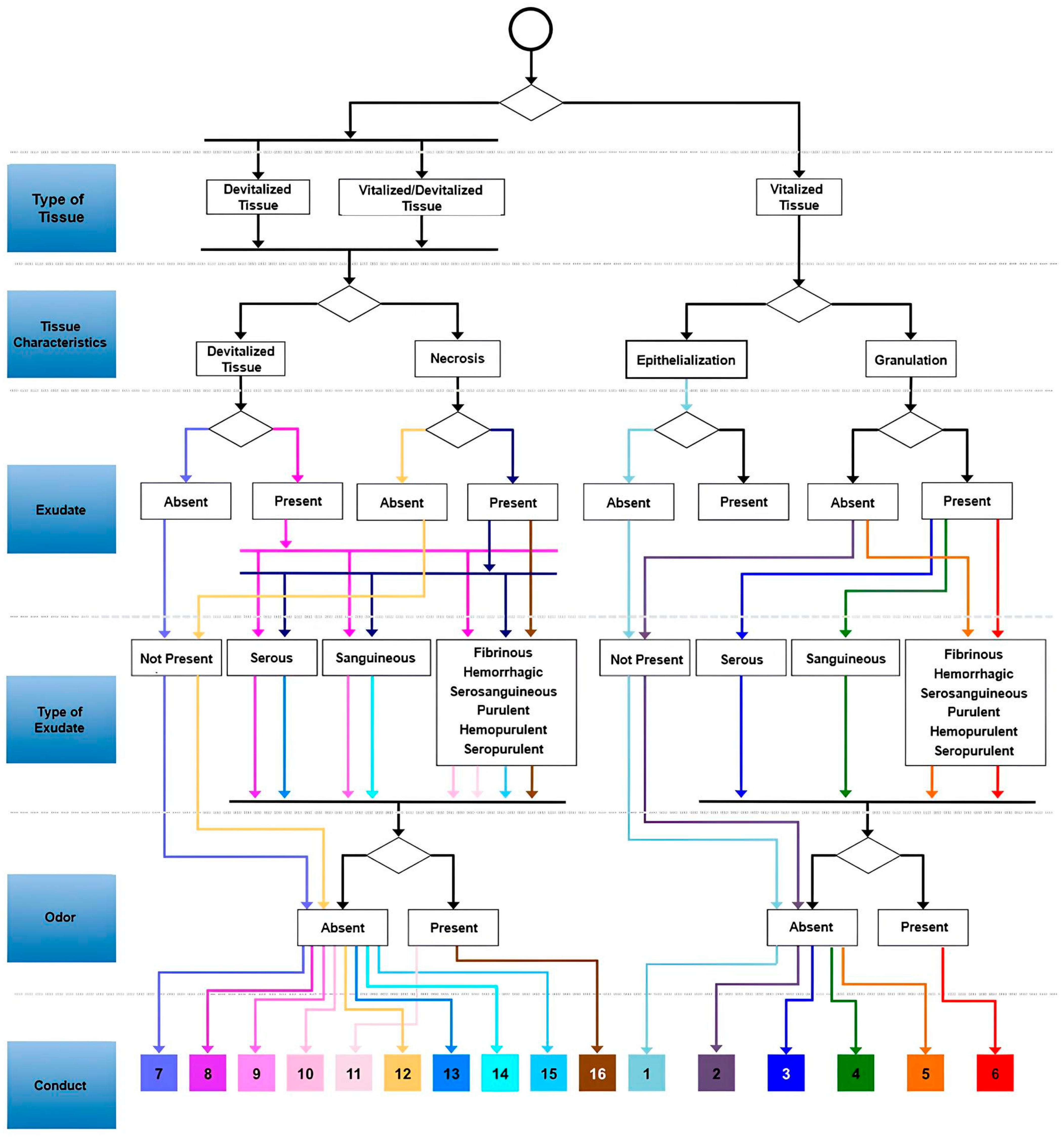

After studying each dressing and/or active agents, they were grouped according to their indication, using the evaluation protocols: TIMERS (only the TIM was used), RYB, and the Wound Assessment Triangle. These protocols allowed for the understanding of the wound characteristics, including tissue type, exudate, and infection, guiding the selection of the appropriate dressing for the wound bed. With this information, it was possible to construct the flowchart (

Figure 1) with the necessary data to be processed by the network.

After organizing the characteristics of the wounds and dressings, the network structure was defined. The proposed neural network follows a sequential model, where the layers are arranged linearly, allowing for a modular and intuitive adjustment of the parameters. The MLP artificial neural network architecture was defined with the following hyperparameters: the network consists of two hidden layers, the first with 128 neurons and the second with 64. To avoid overfitting, a dropout rate of 0.2 was applied after each dense layer. The input layer was sized for the five features of the dataset, and the output layer contained 16 neurons, corresponding to the problem classes, using the softmax activation function to generate the probabilities.

The model was trained for a maximum of 80 epochs with a batch size of 32. Compilation used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and the sparse_categorical_crossentropy loss function. The early stopping technique was configured to monitor the loss on the validation set (val_loss) with a patience of 10 epochs, restoring the model weights to the best iteration found. Additionally, class balancing was performed automatically using class weights to mitigate imbalances in the training dataset.

The outputs of the artificial network consist of 16 possible actions, each associated with a specific group of dressings according to the characteristics of the wound assessed by the professional. Thus, if the network selects action 1, the professional will have available options of dressings to treat a specific wound (

Figure 2).

Table 2 contains the actions and their respective dressings, which were determined based on scientific evidence used in the study.

To ensure full reproducibility of the experiments, all data splitting, model initialization, and testing processes were performed with a fixed randomness seed (seed = 42). The simulation results, validated with a more robust methodology, demonstrated consistent and perfectly replicable performance across all cross-validation folds. The accuracy metrics, F1-macro, ROC-AUC (One-vs-Rest), and PR-AUC (One-vs-Rest), were 1.0 across all replicates, indicating that the model correctly classified all samples.

The permutation test resulted in a

p-value of approximately 0.005 across all folds, suggesting that the probability of the model’s performance occurring by chance is extremely low (less than 0.5%), as seen in

Figure 3.

The stability of the model’s performance across all cross-validation folds is visually confirmed in the

Figure 3. The boxplots demonstrate that the accuracy (a), F1-macro (b), ROC-AUC OVR (c), and PR-AUC OVR (d) metrics did not show any variation, remaining consistently at 1.0, which reinforces the robustness of the results.

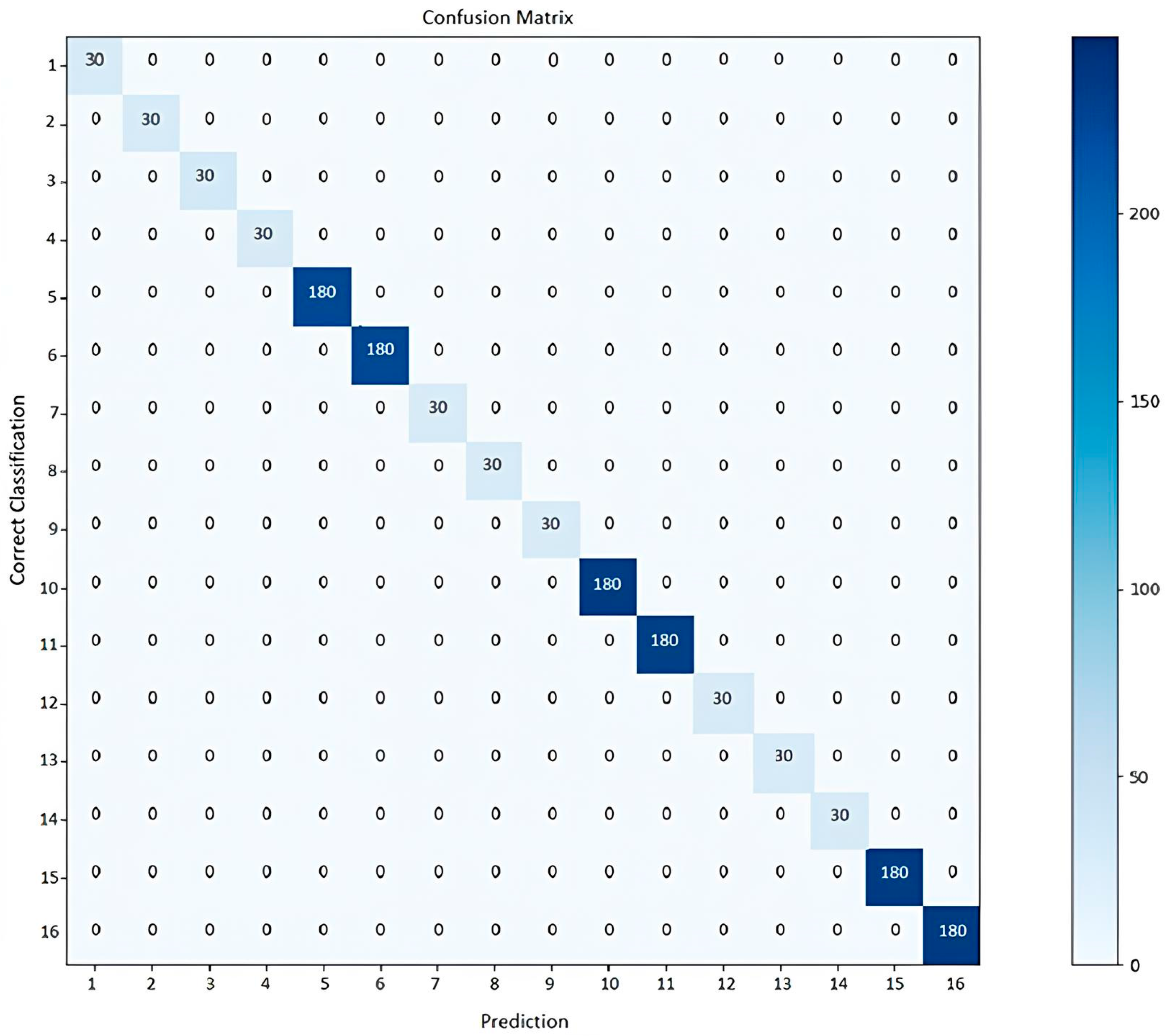

The confusion matrices for each fold confirmed that there were no misclassification errors between classes.

Figure 4 presents the confusion matrix for one of the cross-validation folds as a representative example. The main diagonal shows that all 16 classes were classified correctly, without any errors, corroborating the model’s 100% accuracy.

Benchmark Analysis and Model Comparison

The comparative results, presented in

Table 3 demonstrate that all models achieved identical performance: mean Accuracy = 1.0, F1-macro = 1.0, and ROC-AUC = 1.0 for those capable of probabilistic output. The permutation test (

p ≈ 0.0049) confirmed that this result is statistically significant and not random.

These results indicate that the dataset is highly well-conditioned and nearly deterministic, with the input variables showing strong discriminative power for predicting clinical conduct. The decision boundaries between classes are well separated, resulting in minimal overlap in the feature space and allowing models of different paradigms, such as linear, tree-based, ensemble, and neural, to achieve the same optimal performance.

Given the perfect results across all folds, the data were inspected to ensure the absence of data leakage (such as duplicated cases or variables encoding the target implicitly). After verification, only clinically valid and operational features were retained, confirming that the observed performance represents the intrinsic discriminative structure of the data rather than artifact-induced bias.

Table 3 below summarizes the mean results across models, while

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 graphically depict these findings, showing the mean performance and the stability across folds, respectively.

The results in

Table 3 demonstrate that all algorithms achieved perfect and identical performance metrics across folds. This outcome indicates that the predictive variables are highly informative, leading to a well-conditioned and nearly deterministic problem. The clear separation of classes explains why models of different families, including linear, neighbor-based, ensemble, and neural, converged to the same optimal accuracy.

Although the performance is equivalent, the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) remains the preferred model due to its differentiable architecture and strong integration potential within deep learning frameworks. The MLP can seamlessly connect with modules for image or signal processing, enabling its evolution into a multimodal system for wound analysis. Additionally, it supports multi-label and regression extensions while maintaining a unified training pipeline.

The probabilistic outputs generated by the softmax function allow calibration and uncertainty estimation, which are essential features in clinical decision support. Therefore, even though all models achieved similar quantitative performance, the MLP provides superior extensibility and methodological flexibility, justifying its selection as the core architecture for future system expansions.

For the use of the neural network by healthcare professionals, it was necessary to build the application named VenoTEC. The app contains nine screens that display: welcome information; professional identification (login and password); patient registration with personal information, medical history, physical examination, wound assessment (type, edges, exudate, odor, pain intensity, pruritus) and the wound image with tissue classification. At this stage, the nurse can upload the saved photo to the system, input the wound characteristics, and by clicking on “classify,” a number will appear, with options for coverings, organized into 16 treatment groups. Below are some screens of the VenoTEC app (

Figure 7).

After completing the stages, the developed application was tested for usability. Thirteen nurses participated in the study by using the application and answering the questionnaire based on the System Usability Scale (SUS), which achieved an average of 88.07 points, classifying VenoTEC as having very good usability.

The SUS questionnaire items correspond to Nielsen’s (1993) [

11] usability attributes (12) in specific aspects such as: ease of learning; efficiency; memorability; inconsistencies; user satisfaction. The table below shows the relationship between Nielsen’s usability attributes, the SUS questionnaire, and the responses from the research participants (

Table 4).

Nurses suggested several areas for improvement, such as providing a practical guide for using the app to assist professionals with limited technological affinity and skills; improving the design of the app screens; and enhancing the fields for entering date and time.

4. Discussion

The Artificial Neural Network developed in this study demonstrated positive results in the confusion matrix test and other metrics, achieving a perfect score by selecting appropriate dressings to support the treatment of venous ulcers. Given the available dressing options for treating venous ulcers, the use of technology aids clinical decision-making for dressing selection, allowing nurses to practice in a standardized, accurate manner with real-time evaluation.

A similar application was developed to assist decision-making in the choice of dressings for wounds, aimed at doctors and other primary care professionals. This resource, still under development and yet to be evaluated, is based on an algorithm that analyzes wound characteristics and functions through binary decisions. Compared to the technology in this study, there are similarities in evaluating ulcer characteristics, due to the need for the professional’s expertise in wound care to identify tissue types and feed this information into the technology [

18].

However, there are significant differences in architecture, production method, and execution. The intelligent software developed, VenoTEC, originates from a systematic production process based on critical literature review and structured as a ANN trained with scientific evidence, expert opinions on venous ulcer treatment, and validated protocols to select the appropriate dressing for each wound [

18].

Intelligent technologies like MLP ANNs, within the field of artificial intelligence, are based on the assumption of cognitive functions such as learning, reasoning, computing, perception, and memory, and can be described with such precision that it becomes possible to program a computer to reproduce them. Thus, this technology becomes capable of performing “cognitive” tasks to achieve a specific goal based on the provided information. This computational power is globally transforming healthcare systems [

19].

The power of this technology lies in the ability to acquire billions of unstructured data, extract relevant information, and recognize complex patterns with increasing confidence through massive iterative learning. This capacity to store and learn relevant information is what makes this technology a breakthrough in handling large volumes of data that can be used in real-time clinical practice something that would not be feasible for humans [

20].

The literature highlights gaps in the knowledge and skills of healthcare professionals regarding the topic addressed in this study. Limited high-quality evidence bases were identified for certain types of dressings and treatments for specific patient groups, as well as difficulties in bridging theory and practice and in specialized nursing knowledge. This issue underscores the need for more robust scientific evidence and enhanced wound care education, which can be supported by the use of technologies to encourage knowledge acquisition and facilitate evidence-based clinical practice [

21].

Thus, the importance and necessity of nurses’ leadership in the development and use of these technologies is evident [

22]. The nurse plays a crucial role in guiding and critically evaluating the data that will be input into the technology, as well as in assessing the results, as these are programs prone to errors.

Regarding the evaluation of the VenoTEC application, it achieved what was considered a very good usability rating. Moreover, all nurses considered the application easy to use and noted that its various features were well integrated. A similar study evaluating the usability of an app for monitoring patients with heart failure, both among patients and healthcare professionals, reported similar results, with an average usability score of 81.74 (SD 5.44) for patients and 80.80 for nurses, with higher averages for satisfaction in both groups: 85.76 (SD 11.73) and 83.00 (SD 17.00), respectively [

23].

In another usability test of an app developed to support the clinical practice of nurses, an average score of 76.3 (SD 16.75) was obtained. In this same study, participants who rated the app’s usability lower, particularly in terms of ease of use, struggled with the other evaluations and reported infrequent use of apps, indicating limited familiarity [

24].

Despite technological advancements and the precision of AI-based decision support, healthcare professionals who care for difficult-to-heal wounds, such as venous ulcers, need to adapt to technological changes. Adaptation should focus not only on using technology in clinical practice but also on developing technologies that contribute to healthcare delivery [

20].

Many studies in other fields are advancing work with artificial intelligence. The knowledge of professionals in each field enables dialog between different areas and their concepts, helping to prevent potential biases while also making the research more robust and reliable [

25]. Therefore, collaboration between nurses and information technology professionals is a key aspect in the development of a resource like this, as each specialty contributes its expertise to create a product that meets the necessary objectives and caters to the diverse target audience.

The need for the development of applications that consider the specificities of each age group, as well as the diverse learning aspects of the target audience, is emphasized. Therefore, the design process is crucial in creating functionalities and clear, consistent icons to promote ease of use by users [

24]. In this regard, the literature suggests that quick responses, with the minimum number of screen touches possible, can also be useful for frequent use by professionals in clinical practice [

12]. These factors align with the features of VenoTEC in filling out essential characteristics, with a clear and precise interface, providing a quick response regarding the appropriate type of dressing.

Moreover, the process of evaluating applications is also a fundamental step to identify various inconsistencies, difficulties, and user satisfaction, even after the systematic planning of the software development [

24].

There is rapid growth in mobile technologies, most of which lack accurate evaluations of quality and the real impact on end-users. The evaluation of these resources is an essential step to assess the quality and safety of devices, aiming to ensure effective technologies with an appropriate cost–benefit ratio for the intended audience [

26].

However, there are limited regulatory initiatives to address all the digital products being produced in healthcare, as well as insufficient evaluation strategies that do not clearly and objectively indicate the quality and efficacy of technologies. Therefore, it is necessary to promote evaluations based on standardized and well-defined requirements, guided by the end-user. To achieve this, it is essential to assess technical domains, whether the application truly functions as it should, its clinical efficacy, usability, and cost, both before and after its widespread adoption [

26].

Well-developed and evaluated applications can benefit care by providing access to effective resources, distinguishing them from other digital solutions available in the market [

26]. Especially in wound care, these resources facilitate access to large amounts of useful and relevant information in real-time, optimizing decision-making during evaluation and treatment [

27]. Thus, the nurse can combine their knowledge and evaluative capacity with the use of intelligent technologies to enhance their care for patients with venous ulcers [

9].

In this study, despite the statistical robustness of the experiments, the perfect results obtained (100% in all metrics evaluated) require cautious interpretation. This performance may be related to factors such as the small size of the dataset, the high quality and intrinsic separability of the variables, and the absence of clinical noise, since the data were produced in a controlled environment supervised by experts.

These aspects justify the initial concern regarding the absolute accuracy observed. However, with the adoption of a more rigorous validation methodology—including stratified (5-fold) cross-validation, normalization applied exclusively to the training set, the use of early stopping to avoid overfitting, and permutation tests for statistical verification—the study began to present more consistent quantitative evidence that the model, in fact, captures relevant clinical patterns and does not simply memorize examples from the dataset.

Furthermore, the detailed disclosure of the hyperparameters and experimental procedures ensures methodological transparency and the reproducibility of the results. Nevertheless, the model was compared with established reference algorithms, including logistic regression, support vector machines (SVMs), and tree-based methods, as part of the benchmarking process. These comparisons confirmed that all reference algorithms achieved equivalent performance under the same experimental conditions, reinforcing the robustness and consistency of the results. Future studies may extend these findings by evaluating the model on larger and publicly available datasets, as well as testing its performance using more complex deep learning architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or transformer-based models, which can more deeply explore the spatial or contextual relationships present in clinical data and enhance the model’s generalization capability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S., I.K.F.C.; Methodology: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S., I.K.F.C.; Software: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S., N.C.D.D., I.K.F.C.; Validation: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S., N.C.D.D.; Formal Analysis: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S., I.K.F.C.; Investigation: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S.; Resources: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S.; Data Curation: S.K.C.M., L.S.F., I.P.S., A.A.C.G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: S.K.C.M., L.S.F., I.P.S., A.V.L.N., C.A.A.S., N.C.D.D., R.O.A.; Writing—Review and Editing: S.K.C.M., L.S.F., I.P.S., A.A.C.G., A.V.L.N., C.A.A.S., N.C.D.D., R.O.A., I.K.F.C.; Visualization: S.K.C.M., L.S.F., I.P.S., A.A.C.G., A.V.L.N., C.A.A.S., N.C.D.D., R.O.A., I.K.F.C. Supervision: S.K.C.M., L.S.F., I.P.S., A.V.L.N., C.A.A.S., R.O.A., I.K.F.C. Project Administration: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S., I.K.F.C.; Funding Acquisition: S.K.C.M., C.A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, protocol code 5.165.316, date of approval 15 December 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Author Nielsen Castelo Damasceno Dantas was employed by the company NCDD Technology Ltd. The remaining au-thors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Conferencia Nacional de Consenso Sobre las Úlceras de la Extremidad Inferior. Guía de Consenso. Available online: https://gneaupp.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CONUEIX2018.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Durán-Sáenz, I.; Verdú-Soriano, J.; López-Casanova, P.; Berenguer-Pérez, M. Knowledge and teaching-learning methods regarding venous leg ulcers in nursing professionals and students: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 63, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-García, J.F.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Arboledas-Bellón, J.; Gutiérrez-García, M.; González-Jiménez, F.; Lafuente-Robles, N.; Parra-Anguita, L.; García-Fernández, F.P. The effectiveness of advanced practice nurses with respect to complex chronic wounds in the management of venous ulcers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylönen, M.; Viljamaa, J.; Isoaho, H.; Junttila, K.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Suhonen, R. Congruence between perceived and theoretical knowledge before and after an internet-based continuing education program about venous leg ulcer nursing care. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 83, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, G.M.; Desai, K.R. Team-based approach to deep venous disease: A multidisciplinary approach to the multifaceted problem of thrombotic lower extremity venous disease. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinc, O.H. Healing takes a team: Why venous surgeons and tissue viability nurses must work together. Lindsay Leg Club Tissue Viability Serv. Venous Leg Ulcer Wounds UK 2025, 21, 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, N.; Rappon, T.; Berta, W. Applications of artificial neural networks in health care organizational decision-making: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, S.K.C.; Freitas, L.S.; Gonçalves, A.A.C.; Linhares, J.D.S.O.; Araújo, R.O.; Costa, I.K.F. Coverings and topical agents and their effects on the treatment of venous lesions: Integrative review. Rev. Enferm. UFPI 2023, 12, e3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.S.C. Feridas & Curativos: Guia Prático de Condutas, 1st ed.; Editora Sanar: Salvador, Brazil, 2020; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Atkin, L.; Bućko, Z.; Montero, E.C.; Cutting, K.; Moffatt, C.; Probst, A.; Romanelli, M.; Schultz, G.S.; Tettelbach, W. Implementing TIMERS: The race against hard-to-heal wounds. J. Wound Care 2019, 23, S1–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, A.R.; Clemente, P.I.; Moratilla, C.A.; Gómez, S.R.; Tormo, M.T.C.; Vargas, P.G.; Barreno, D.P.; Caballero, M.A.N.; Imas, G.E.; Agúndez, A.F.; et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica: Consenso Sobre Úlceras Vasculares y Pie Diabético de la Asociación Española de Enfermería Vascular y Heridas (AEEVH), 3rd ed.; AEEVH: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Springer: London, UK, 1996; pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Scikit-Learn. Cross-Validation: Evaluating Estimator Performance. Scikit-Learn Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/cross_validation.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Arlot, S.; Celisse, A. A survey of cross-validation procedures for model selection. Stat. Surv. 2010, 4, 40–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, S.; Simon, R. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Projetando Websites: Designing Web Usability, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S.; McSwiggan, J.; Parker, J.; Halas, G.A.; Friesen, M. An mHealth App for Decision-Making Support in Wound Dressing Selection (WounDS): Protocol for a User-Centered Feasibility Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, J.M.; Swiergosz, A.M.; Haeberle, H.S.; Karnuta, J.M.; Schaffer, J.L.; Krebs, V.E.; Spitzer, A.I.; Ramkumar, P.N. Machine learning and artificial intelligence: Definitions, applications, and future directions. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2020, 13, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, T.; Kalakota, R. The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future Healthc. J. 2019, 6, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, L. Wound care evidence, knowledge and education amongst nurses: A semi-systematic literature review. Int. Wound J. 2018, 15, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat-Johnson, M.; Jones, A.; Burger, M.; Leong, T.; Frotjold, A.; Randall, S.; Kim, B.; Fethney, J.; Coyer, F. Reshaping wound care: Evaluation of an artificial intelligence app to improve wound assessment and management amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Wound J. 2022, 19, 1561–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y. A smart-phone app for fluid balance monitoring in patients with heart failure: A usability study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 1843–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrler, F.; Weinhold, T.; Joe, J.; Lovis, C.; Blondon, K. A mobile app (BEDSide Mobility) to support nurses’ tasks at the patient’s bedside: Usability study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubas, M.R.; Maria, C.; Carvalho, D.R. Formação interdisciplinar na área de informática em saúde e a inserção de egresso. Rev. Tecnol. Soc. 2020, 16, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.C.; McShea, M.J.; Hanley, C.L.; Ravitz, A.; Labrique, A.B.; Cohen, A.B. Digital health: A path to validation. npj Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamloul, N.; Ghias, M.H.; Khachemoune, A. The Utility of Smartphone Applications and Technology in Wound Healing. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2019, 18, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).